Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine Hesitancy in South Tyrol

3.2. General Practitioners as Trusted Sources

3.3. Communication Strategies

3.3.1. Overview of Effective Communication

3.3.2. Visual Aids, Personalizing the Message, and Engaging in Motivational Interviewing

3.3.3. Challenges in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Regions

4. Discussion

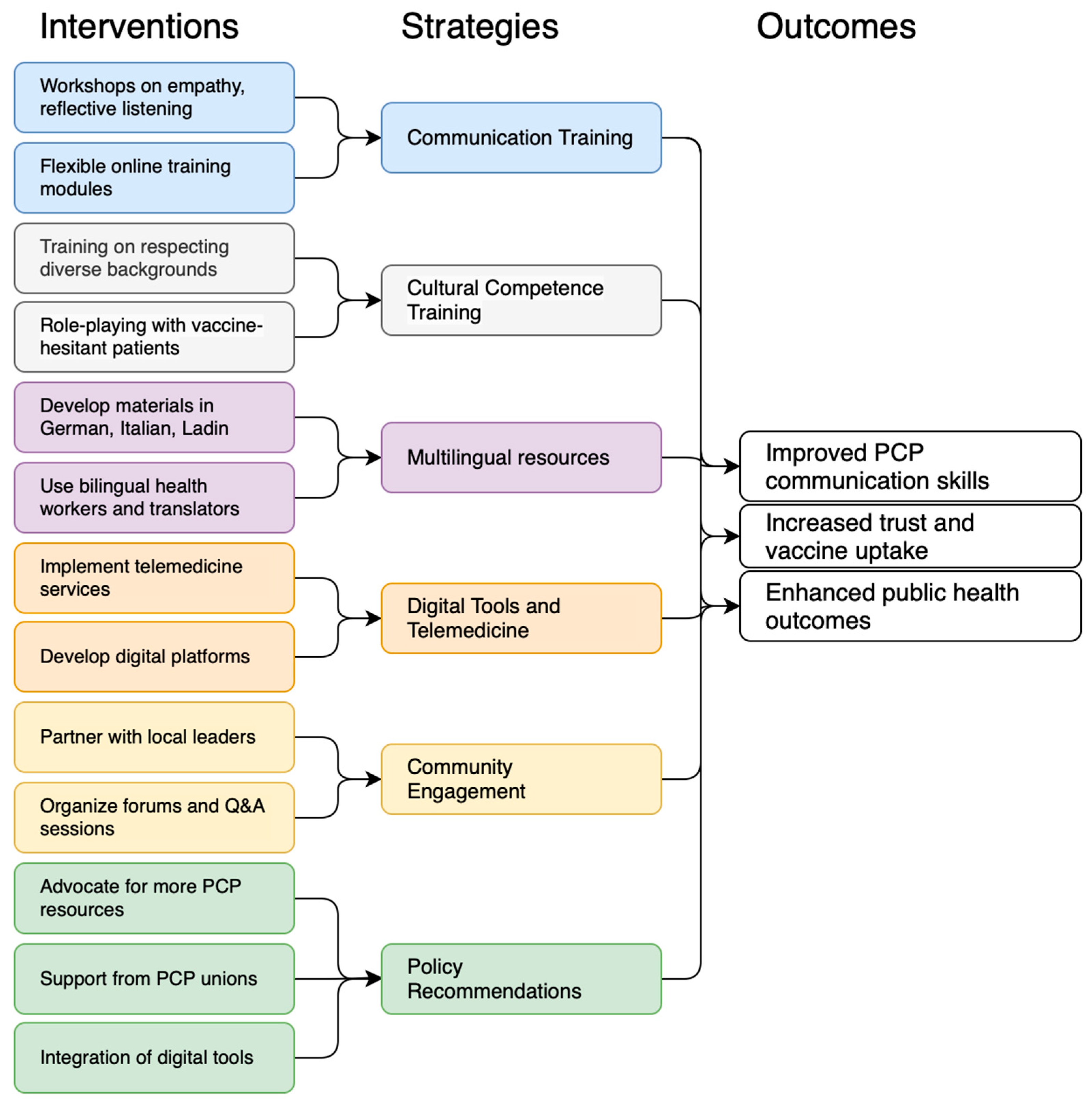

Proposed Strategy

- GPs should provide clear and transparent information about vaccine safety, efficacy, and potential adverse effects, acknowledging the uncertainties in building trust. Empathic communication, including understanding and acknowledging concerns and using reflective listening, is essential. Tailoring information to a patient’s medical history, cultural background, and personal concerns makes communication more relevant and persuasive [33].

- Training programs for GPs can enhance their communication skills. Workshops should include empathic communication, reflective listening, clear information, and cultural competencies. Role-playing with actors can provide hands-on experience. To accommodate overburdened GPs, training should be flexible and accessible using online modules, short videos, and interactive e-learning schedules.

- Addressing GP workload and motivation is critical. Integrating communication training into CME credits ensures that skills are updated. Financial incentives or recognition can motivate GPs, whereas peer learning groups and mentorship programs can provide ongoing support and encouragement.

- Effective communication increases vaccine uptake and implementation of new clinical practices. Five recommendations have been made to facilitate this process. Clearly explain the rationale and benefits of the new practices, provide adequate training, use multiple communication channels, and communicate changes effectively in advance. Allowing for feedback and engagement fosters ownership and addresses concerns, helps overcome resistance, and supports implementation [45].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CME | Continuing Medical Education |

| EMBASE | Excerpta Medica Database |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| PCP | Primary Care Physician |

| Q&A | Question and Answer |

| HCW | Health Care Worker |

References

- World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Galagali, P.M.; Kinikar, A.A.; Kumar, V.S. Vaccine Hesitancy: Obstacles and Challenges. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 10, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Ramzan, I.; Weekes, L.; Kayser, V. Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavić, Ž.; Kovačević, E.; Šuljok, A. Health Literacy, Religiosity, and Political Identification as Predictors of Vaccination Conspiracy Beliefs: A Test of the Deficit and Contextual Models. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Russell, C.M.; Jankovsky, A.; Cannon, T.D.; Pittenger, C.; Pushkarskaya, H. Information Processing Style and Institutional Trust as Factors of COVID Vaccine Hesitancy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; White, T.M.; Wyka, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Rabin, K.; Larson, H.J.; Martinon-Torres, F.; Kuchar, E.; Abdool Karim, S.S.; Giles-Vernick, T.; et al. Influence of COVID-19 on Trust in Routine Immunization, Health Information Sources and Pandemic Preparedness in 23 Countries in 2023. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1559–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.M.; St Sauver, J.L.; Finney Rutten, L.J. Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeuser, E.; Byrne, S.; Nguyen, J.; Raggi, C.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Bisignano, C.; Harris, A.A.; Smith, A.E.; Lindstedt, P.A.; Smith, G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Trends in Routine Childhood Vaccination Coverage from 1980 to 2023 with Forecasts to 2030: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M. Language and Cultural Norms Influence Vaccine Hesitancy. Nature 2024, 627, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy in South Tyrol: A Narrative Review of Insights and Strategies for Public Health Improvement. Ann. Ig. 2024, 36, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.; Sergent, S.R. Language Barrier. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Keselman, A.; Arnott Smith, C.; Wilson, A.J.; Leroy, G.; Kaufman, D.R. Cognitive and Cultural Factors that Affect General Vaccination and COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes. Vaccines 2023, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, J.-Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Zhao, I. Barriers and Enablers to Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines in Primary Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e062158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Torkamani, A.; Butte, A.J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Schuller, B.; Rodriguez, B.; Ting, D.S.W.; Bates, D.; Schaden, E.; Peng, H.; et al. The Promise of Digital Healthcare Technologies. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1196596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Ausserhofer, D.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Wiedermann, W.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy during the Coronavirus Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Linguistic Correlates in a Representative Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlini, O. The South-Tyrol Autonomy in Italy: Historical, Political and Legal Aspects. In One Country, Two Systems, Three Legal Orders—Perspectives of Evolution: Essays on Macau’s Autonomy After the Resumption of Sovereignty by China; Oliveira, J.C., Cardinal, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-540-68571-5. [Google Scholar]

- Piccoliori, G.; Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Engl, A. Special Roles of Rural Primary Care and Family Medicine in Improving Vaccine Hesitancy. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candio, P.; Violato, M.; Clarke, P.M.; Duch, R.; Roope, L.S. Prevalence, Predictors and Reasons for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Results of a Global Online Survey. Health Policy 2023, 137, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurstak, E.E.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Hahn, E.A.; Henault, L.E.; Taddeo, M.A.; Moreno, P.I.; Weaver, C.; Marquez, M.; Serrano, E.; Thomas, J.; et al. The Mediating Effect of Health Literacy on COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence among a Diverse Sample of Urban Adults in Boston and Chicago. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2562–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, E.B.; Frank, E. Physicians’ Health Practices Strongly Influence Patient Health Practices. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2009, 39, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDougall, D.M.; Halperin, B.A.; MacKinnon-Cameron, D.; Li, L.; McNeil, S.A.; Langley, J.M.; Halperin, S.A. The Challenge of Vaccinating Adults: Attitudes and Beliefs of the Canadian Public and Healthcare Providers. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Campo, Á.; García-Álvarez, R.M.; López-Durán, A.; Roque, F.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A.; Zapata-Cachafeiro, M. Understanding Primary Care Physician Vaccination Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, H.S.; French, C.E.; Caldwell, D.M.; Letley, L.; Mounier-Jack, S. A Systematic Review of Communication Interventions for Countering Vaccine Misinformation. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhánková, J.H.; Kotherová, Z.; Numerato, D. Navigating Vaccine Hesitancy: Strategies and Dynamics in Healthcare Professional-Parent Communication. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2361943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagna, K.; Becker, A.; Valeris-Chacin, R.; Mohammed, I.; Tambe, S.; Awan, F.A.; Toomey, T.L.; Basta, N.E. Global Assessment of National Mandatory Vaccination Policies and Consequences of Non-Compliance. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7865–7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanizzi, P.; Bianchi, F.P.; Brescia, N.; Ferorelli, D.; Tafuri, S. Vaccination Strategies between Compulsion and Incentives. The Italian Green Pass Experience. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mauro, A.; Di Mauro, F.; De Nitto, S.; Rizzo, L.; Greco, C.; Stefanizzi, P.; Tafuri, S.; Baldassarre, M.E.; Laforgia, N. Social Media Interventions Strengthened COVID-19 Immunization Campaign. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 869893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzhath, T.; Spiegelman, A.; Scobee, J.; Goidel, K.; Washburn, D.; Callaghan, T. Primary Care Physicians’ Strategies for Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 333, 116150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikow, J.; Padovani, A.; Zhang, J.; Miller, M.; Gosdin, M.; Loureiro, S.; Daniels, B. Patient Concerns and Physician Strategies for Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3300–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Wiedermann, W.; Becker, U.; Vögele, A.; Piccoliori, G.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Engl, A. Health Information-Seeking Behavior Associated with Linguistic Group Membership: Latent Class Analysis of a Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey in Italy, August to September 2014. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaser, F.A. Effective Communication Skills and Patient’s Health. CPQ Neurol. Psychol. 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, M.S.; Alden-Rivers, B. Developing a Framework for Sustainable Growth of Flexible Learning Opportunities. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2019, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Schmid, P.; Habersaat, K.B.; Nielsen, S.M.; Seale, H.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Geiger, M.; Craig, B.; Sunstein, C.; et al. Lessons from COVID-19 for Behavioural and Communication Interventions to Enhance Vaccine Uptake. Commun. Psychol. 2023, 1, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, A.; Stefanizzi, P.; Tafuri, S. Are We Saying It Right? Communication Strategies for Fighting Vaccine Hesitancy. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1323394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial. Data Access Needed to Tackle Online Misinformation. Nature 2024, 630, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Piccoliori, G.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Engl, A. The Role of Homogeneous Waiting Group Criteria in Patient Referrals: Views of General Practitioners and Specialists in South Tyrol, Italy. Healthcare 2024, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticozzi, E.M.; Gaetti, G.; Gambolò, L.; Bottignole, D.; Di Fronzo, P.; Solla, D.; Stirparo, G. Navigating Vaccine Misinformation: Assessing Newly Licensed Physicians’ Ability to Distinguish Facts from Fake News. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoef, N.C.; Blomme, R.J. Burnout among General Practitioners, a Systematic Quantitative Review of the Literature on Determinants of Burnout and Their Ecological Value. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1064889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, P.H. What Makes Workers Happy: Empowerment, Unions or Both? Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2019, 25, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finset, A.; Ørnes, K. Empathy in the Clinician–Patient Relationship. J. Patient Exp. 2017, 4, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bussche, H. Die Zukunftsprobleme der hausärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland: Aktuelle Trends und notwendige Maßnahmen. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2019, 62, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, C.; Wilson, R.; O’Leary, M.; Eckersberger, E.; Larson, H.J. Strategies for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy—A Systematic Review. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4180–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, S.T.; Opel, D.J.; Cataldi, J.R.; Hackell, J.M.; Committee on Infectious Diseases; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; Committee on Bioethics. Strategies for Improving Vaccine Communication and Uptake. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023065483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handtke, O.; Schilgen, B.; Mösko, M. Culturally Competent Healthcare—A Scoping Review of Strategies Implemented in Healthcare Organizations and a Model of Culturally Competent Healthcare Provision. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, K.; Navarro, E.I.; Jarad, I.; Boyd, M.R.; Powell, B.J.; Lewis, C.C. Communication Strategies to Facilitate the Implementation of New Clinical Practices: A Qualitative Study of Community Mental Health Therapists. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureaucracy Busting Concordat: Principles to Reduce Unnecessary Bureaucracy and Administrative Burdens on General Practice. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bureaucracy-busting-concordat-principles-to-reduce-unnecessary-bureaucracy-and-administrative-burdens-on-general-practice/bureaucracy-busting-concordat-principles-to-reduce-unnecessary-bureaucracy-and-administrative-burdens-on-general-practice (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Barbosa, W.; Zhou, K.; Waddell, E.; Myers, T.; Dorsey, E.R. Improving Access to Care: Telemedicine Across Medical Domains. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanizzi, P.; Provenzano, S.; Santangelo, O.E.; Dallagiacoma, G.; Gianfredi, V. Past and Future Influenza Vaccine Uptake Motivation: A Cross-Sectional Analysis among Italian Health Sciences Students. Vaccines 2023, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomietto, M.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V.; Papappicco, C.A.M.; Stefanizzi, P.; Mercuri, M.; Cicolini, G. Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccination in the Nursing Profession: Validation of the Italian Version of the VAX Scale and Descriptive Study. Ann. Ig. 2022, 34, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, L.N.; Kahn, B.Z.; Kokitkar, S.; Kritikos, K.I.; Brantz, S.N.; Brewer, N.T. HPV Vaccine Standing Orders and Communication in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3981–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Communication Techniques | |

| Clear and Transparent Communication | Provide straightforward information about vaccine safety, efficacy, and potential side effects. |

| Empathy and Reflective Listening | Understand and acknowledge patients’ concerns; establish a non-judgmental relationship. |

| Personalized Information | Tailor information to patients’ medical history, cultural background, and personal concerns. |

| Training Programs | |

| Workshops on Communication Skills | Focus on advanced communication techniques and cultural competence. |

| Cultural Competence Training | Help GPs understand and respect diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. |

| Language Training and Simulations | Provide vaccination-specific language training in German and Italian; use simulation exercises. |

| Flexible and Accessible Training | Offer online modules, short video tutorials, and interactive e-learning platforms. |

| Addressing Workload and Motivation | |

| Incorporate Training into Routine Work | Integrate communication training into regular meetings and CME credits. |

| Incentivize Participation | Offer financial incentives or recognition for completing training programs. |

| Support Systems | Establish peer learning groups or mentorship programs for ongoing support. |

| Develop a centralized online platform where GPs can access accurate, evidence-based information about vaccines, tailored communication strategies, and updates on public health policies. | |

| Implementation Communication | |

| Communication of the Intervention | Explain the reasons for adopting new practices; use various communication channels; communicate changes well in advance; encourage feedback and engagement. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiedermann, C.J.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030050

Wiedermann CJ, Piccoliori G, Engl A. Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiedermann, Christian J., Giuliano Piccoliori, and Adolf Engl. 2025. "Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy" Epidemiologia 6, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030050

APA StyleWiedermann, C. J., Piccoliori, G., & Engl, A. (2025). Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy. Epidemiologia, 6(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030050