Adapting Ophthalmology Practices in Puerto Rico During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

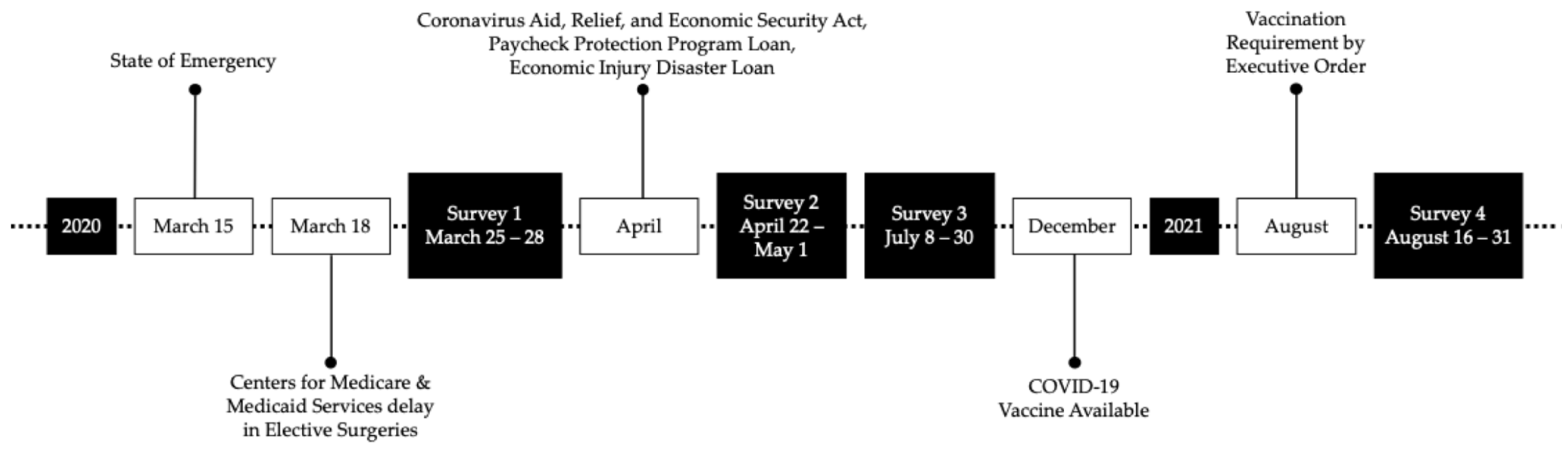

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Adaptations in Ophthalmology Clinical Practices

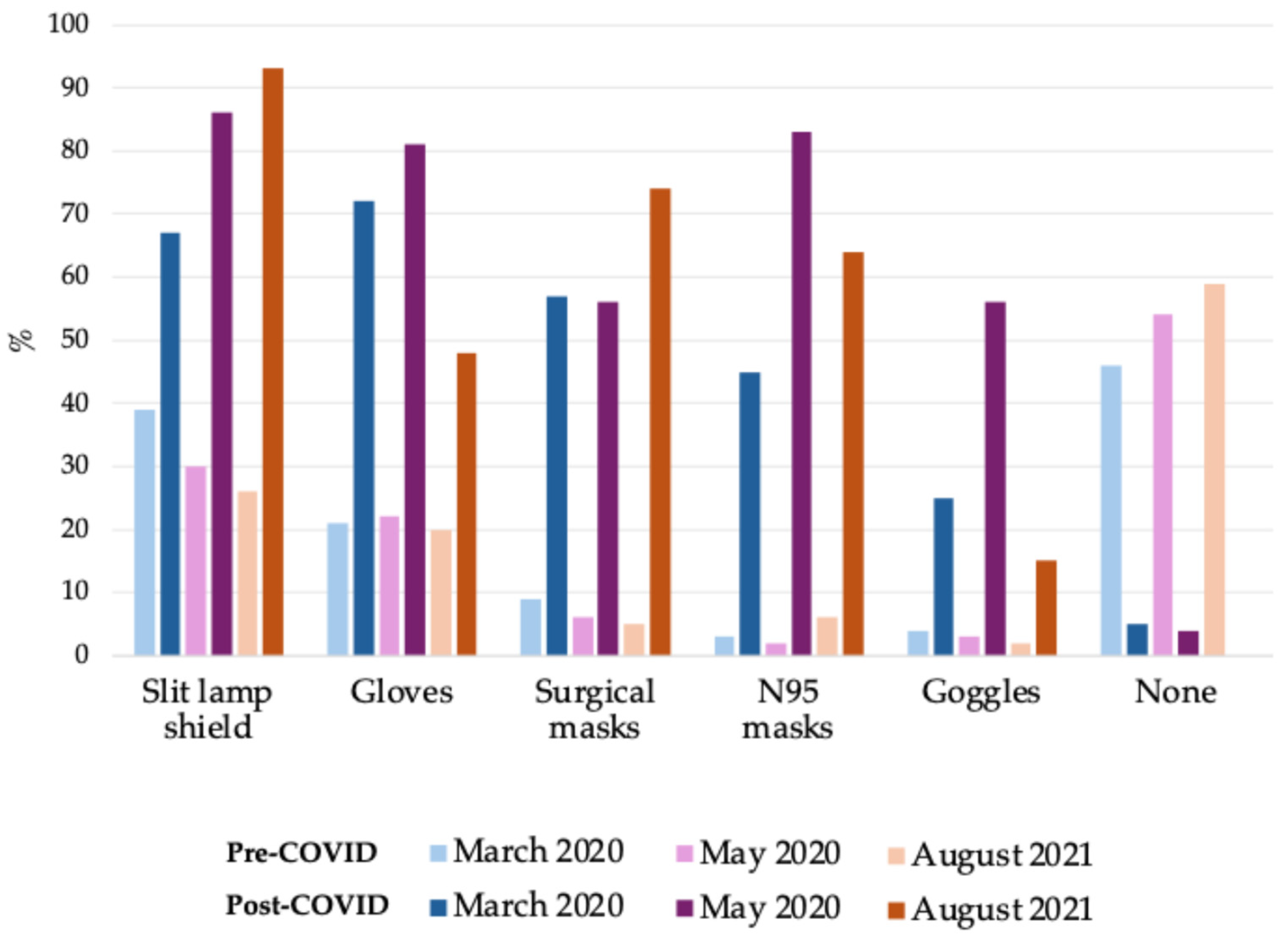

3.3. PPE Usage

3.4. Federal Financial Assistance

3.5. COVID-19 Vaccination, Screening, and Control

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Context and Its Implications

4.2. Guidance and Response Time

4.3. Personal Protective Equipment Utilization and Challenges

4.4. Telemedicine

4.5. Financial Assistance

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Lessons Learned and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PR | Puerto Rico |

| U.S. | United States |

References

- Hoeferlin, C.; Hosseini, H. Review of Clinical and Operative Recommendations for Ophthalmology Practices During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebmann, J.M. Ophthalmology and Glaucoma Practice in the COVID-19 Era. J. Glaucoma 2020, 29, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.D.; Brézin, A.P.; Burdon, M.; Cummings, A.B.; Kemer, O.E.; Malyugin, B.E.; Prieto, I.; Teus, M.A.; Tognetto, D.; Törnblom, R.; et al. Early impact of COVID-19 outbreak on eye care: Insights from EUROCOVCAT group. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, N. Coronavirus: Puerto Rico Needs Medical Supplies but Faces Restrictions. NBC News, 21 March 2020. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/coronavirus-puerto-rico-needs-medical-supplies-faces-restrictions-n1165751 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- García, C.; Rivera, F.I.; Garcia, M.A.; Burgos, G.; Aranda, M.P. Contextualizing the COVID-19 Era in Puerto Rico: Compounding Disasters and Parallel Pandemics. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e263–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.A.; Quigley, D.D.; Chastain, A.M.; Ma, H.S.; Shang, J.; Stone, P.W. Urban and Rural Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes in the United States: A Systematic Review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2025, 82, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Madera, S.L.; Varas-Díaz, N.; Padilla, M.; Grove, K.; Rivera-Bustelo, K.; Ramos, J.; Contreras-Ramirez, V.; Rivera-Rodríguez, S.; Vargas-Molina, R.; Santini, J. The impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s health system: Post-disaster perceptions and experiences of health care providers and administrators. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2021, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, M.; Becerra, J.E.; Reyes, J.C.; Castro, K.G. Assessment of early mitigation measures against COVID-19 in Puerto Rico: March 15–May 15, 2020. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Non-Emergent, Elective Medical Services, and Treatment Recommendations. 2020. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Recommendations for Urgent and Nonurgent Patient Care. 2020. Available online: https://www.aao.org/education/headline/new-recommendations-urgent-nonurgent-patient-care (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Nie, J.; Laditi, F.; Leapman, M.S. Distribution of Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund Assistance to Urology Practices. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Did the small business administration’s COVID-19 assistance go to the hard hit firms and bring the desired relief? J. Econ. Bus. 2021, 115, 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Member Pulse Survey: Telemedicine Usage Declines as Patient Volume Grows. 2020. Available online: https://www.aao.org/about/governance/academy-blog/post/covid-survey-telemedicine-usage-patient-volume (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Evan, M.; Chen, B.; Ravi Parikh, M.D. COVID-19 and Ophthalmology: The Pandemic’s Impact on Private Practices. Eyenet24 2020. Available online: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/pandemic-impact-on-private-practices (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Hahn, P.; Blim, J.F.; Packo, K.; Jumper, J.M.; Murray, T.; Awh, C.C. The Impact of COVID-19 on US and International Retina Specialists, Their Practices, and Their Patients. J. Vitr. Dis. 2022, 6, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Order of the Governor of Puerto Rico, Hon. Pedro R. Pierluisi, for the Purposes of Requiring Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccinations and Screening for the Restaurant, Bar, Theater, Cinema, Stadium, and Activity Center Sectors, Among Others. 2021. Available online: https://docs.pr.gov/files/Estado/OrdenesEjecutivas/2021/OE-2021-063-%20English.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Executive Order of the Governor of Puerto Rico Hon Pedro, R. Pierluisi, for the Purposes of Implementing Measures to Combat COVID-19 at Gyms, Beauty Salons, Barber Shops, Spas, Child Care Centers, Casinos, Grocery Stores, and Convenience Stores Among Others. 2021. Available online: https://docs.pr.gov/files/Estado/OrdenesEjecutivas/2021/OE-2021-064%20English.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- National Provider Identifier Database. National Provider Identifier Database, Ophthalmology Puerto Rico. Available online: https://npidb.org/doctors/allopathic_osteopathic_physicians/ophthalmology_207w00000x/pr/?page=1 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Your COVID-19 Experience Drives Academy Efforts on Your Behalf. 2020. Available online: https://www.aao.org/about/governance/academy-blog/post/your-covid-19-experience-drives-academy-efforts (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Asch, S.; Connor, S.E.; Hamilton, E.G.; Fox, S.A. Problems in recruiting community-based physicians for health services research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.D. Solo Practice in Ophthalmology: Resisting the Tides? EyeNet Magazine: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/solo-practice-in-ophthalmology (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Sirkin, J.T.; Flanagan, E.; Tong, S.T.; Coffman, M.; McNellis, R.J.; McPherson, T.; Bierman, A.S. Primary Care’s Challenges and Responses in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from AHRQ’s Learning Community. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlette, S.; Berenson, R.A.; Wengle, E.; Lucia, K.; Thomas, T. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Primary Care Practices; Urban Institute: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.S.; Ryniker, L.; Schwartz, R.M.; Shaam, P.; Finuf, K.D.; Corley, S.S.; Parashar, N.; Young, J.Q.; Bellehsen, M.H.; Jan, S. Physician challenges and supports during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1055495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.W.; Ahluwalia, A.; Feng, H.; Adelman, R.A. National Trends in the United States Eye Care Workforce from 1995 to 2017. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 218, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, R.; Telner, D.; Butt, D.A.; Krueger, P.; Fleming, K.; MacDonald, S.; Pyakurel, A.; Greiver, M.; Jaakkimainen, L. Factors associated with plans for early retirement among Ontario family physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Escobar, F.J.; Sánchez-Cano, D.; Lasave, A.F.; Soria, J.; Franco-Cárdenas, V.; Reviglio, V.; Dantas, P.E.; Pastrana, C.P.; Corbera, J.C.; Chan, R.Y.; et al. Early-Phase Perceptions of COVID-19’s Impact on Ophthalmology Practice Patterns: A Survey from the Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 3249–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra, A.; Chernew, M.; Linetsky, D.; Hatch, H.; Cutler, D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Oupatient Visist: A Rebound Emerges. 2020. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Jarenwattananon, P.; Bior, A.; Handel, S. Why Puerto Rico leads the U.S. in COVID vaccine rate—And what states can learn. The Coronavirus Crisis. 2021. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/10/27/1049323911/puerto-rico-leads-the-us-in-covid-19-vaccine-rates-and-what-states-can-learn (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Perez Semanaz, S. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Puerto Rico. 2020. Available online: https://www.american.edu/cas/news/catalyst/covid-19-in-puerto-rico.cfm (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Goniewicz, K.; Goniewicz, M.; Włoszczak-Szubzda, A.; Lasota, D.; Burkle, F.M.; Borowska-Stefańska, M.; Wiśniewski, S.; Khorram-Manesh, A. The Moral, Ethical, Personal, and Professional Challenges Faced by Physicians during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. In Show of COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence, 96% of America’s Ophthalmologists Already Vaccinated. 2021. Available online: https://www.aao.org/newsroom/news-releases/detail/96-percent-of-americas-ophthalmologists-vaccinated (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Syed, A.A.O.; Jahan, S.; Aldahlawi, A.A.; Alghazzawi, E.A. Preventive Practices of Ophthalmologists During COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauchegger, T.; Osl, A.; Nowosielski, Y.; Angermann, R.; Palme, C.; Haas, G.; Steger, B. Effects of COVID-19 protective measures on the ophthalmological patient examination with an emphasis on gender-specific differences. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021, 6, e000841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Important Coronavirus Updates for Ophthalmologists. 2020. Available online: https://www.aao.org/education/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Hu, V.; Wolvaardt, E. Ophthalmology during COVID-19: Who to see and when. Community Eye Health 2020, 33, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, T.H.T.; Tang, E.W.H.; Chau, S.K.Y.; Fung, K.S.C.; Li, K.K.W. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: An experience from Hong Kong. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.W.; Liu, X.F.; Jia, Z.F. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet 2020, 395, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Deng, C.; Zou, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, X. The evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection on ocular surface. Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Ali, M.; Bleasdale, S.C.; Lora, A.J.M. Cost of personal protective equipment during the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1897–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenia, A.; Li, P.; Seefeldt, R.; Seitzman, G.D.; Sun, C.Q.; Kim, T.N. Longitudinal Use of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Utility of Asynchronous Testing for Subspecialty-Level Ophthalmic Care. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, D.B. Is There a Future for Telehealth in Ophthalmology? JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lott, L.B.; Newman-Casey, P.A.; Lee, P.P.; Ballouz, D.; Azzouz, L.; Cho, J.; Valicevic, A.N.; Woodward, M.A. Change in Ophthalmic Clinicians’ Attitudes Toward Telemedicine During the Coronavirus 2019 Pandemic. Telemed. e-Health 2021, 27, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.M.; Pasquale, L.R.; Sidoti, P.A.; Tsai, J.C. Virtual Ophthalmology: Telemedicine in a COVID-19 Era. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 216, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.W.; Young, K.Z.; Johnson, M.W.; Young, B.K. Workforce separation among ophthalmologists before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2024, 262, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HHS Distributing $1.75 Billion in Provider Relief Fund Payments to Health Care Providers Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2022. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/press-releases/hhs-distributing-additional-provider-relief-fund-payments (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- García Lorente, M.; Zamorano Martín, F.; Rodríguez Calvo de Mora, M.; Rocha-de-Lossada, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ophthalmic emergency services in a tertiary hospital in Spain. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, NP313–NP315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, Y.C.; Husain, R.; Teo, K.Y.C.; Tan, A.C.S.; Chew, A.C.Y.; Ting, D.S.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Tan, G.S.W.; Wong, T.Y. New digital models of care in ophthalmology, during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 March 2020 | 2 May 2020 | 3 July 2020 | 4 August 2021 | |||||

| (n = 111) | (n = 93) | (n = 82) | (n = 81) | |||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Age Group | ||||||||

| 25–34 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| 35–44 | 29 | 26 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 21 |

| 45–54 | 31 | 28 | 26 | 28 | 24 | 29 | 21 | 26 |

| 55–64 | 28 | 25 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 26 | 23 | 28 |

| 65+ | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 | 19 | 23 | 14 | 17 |

| Subspecialty a | ||||||||

| Comprehensive | 67 | 60 | 59 | 63 | 46 | 56 | 56 | 69 |

| Medical and Surgical Retina | 20 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 21 | 18 | 22 |

| Glaucoma | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 12 |

| Cornea | 12 | 11 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 7 | 9 |

| Medical Retina | 7 | 6 | * | * | * | * | 5 | 6 |

| Oculoplastics | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Pediatric or Strabismus | * | * | 5 | 5 | * | * | * | * |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Uveitis | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Geographic health district a | ||||||||

| Metropolitan | 50 | 45 | 46 | 49 | 41 | 50 | 40 | 49 |

| Mayagüez | 14 | 13 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 7 |

| Arecibo | 13 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 20 | 11 | 14 |

| Bayamón | 12 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 16 |

| Caguas | 10 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 11 |

| Ponce | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| Fajardo | * | * | 6 | 6 | * | * | * | * |

| Practice type b | ||||||||

| Solo Practitioner | 66 | 59 | 55 | 59 | 47 | 57 | 39 | 48 |

| Small Group (<5) | 27 | 24 | 25 | 27 | 18 | 22 | 28 | 35 |

| Large Group (≥5) | 18 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 16 |

| University Setting | 17 | 15 | 12 | 13 | * | * | 7 | 9 |

| Veterans Hospital | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | * | * |

| Fondo | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | – |

| Survey | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 March 2020 | 2 May 2020 | 3 July 2020 | ||||

| (n = 111) | (n = 93) | (n = 82) | ||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Office hours | ||||||

| Open | 86 | 77 | 72 | 77 | 82 | 100 |

| Emergency only | – | – | 63 | 88 | 4 | 5 |

| All visits | – | – | 9 | 13 | 78 | 95 |

| Closed | 24 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | <1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Patient volume if open | ||||||

| 25% or less of usual | 55 | 64 | 64 | 89 | 5 | 6 |

| 50% of usual | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 23 | 28 |

| 75% of usual | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 61 |

| 100% of usual | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Missing | 28 | 33 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 May 2020 | 3 July 2020 | |||

| (n = 93) | (n = 82) | |||

| No | % | No | % | |

| Applied for a Paycheck Protection Program Loan | ||||

| Applying | 53 | 57 | 2 | 2 |

| Approved | 17 | 18 | 65 | 79 |

| Ineligible because of other reasons | 10 | 11 | 7 | 9 |

| Heard of loan, would like more information | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Ineligible because office is closed | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Do not know about the loan | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Applied for Economic Injury Disaster Loan | ||||

| Not interested | 35 | 38 | 33 | 40 |

| Do not know about the loan | 24 | 26 | 18 | 22 |

| Applied/applying | 18 | 19 | 19 | 23 |

| Heard of loan, would like more information | 9 | 10 | 3 | 4 |

| Ineligible | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| Received Health and Human Services Stimulus Grant | ||||

| Received | 66 | 71 | 64 | 78 |

| Not received | 17 | 18 | 9 | 11 |

| Do not know if I, my group, or my employer received | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 |

| Do not know about the grant | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hailu, S.; Ponce, A.N.; Charak, J.; Jimenez, H.; Al-Attar, L. Adapting Ophthalmology Practices in Puerto Rico During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030042

Hailu S, Ponce AN, Charak J, Jimenez H, Al-Attar L. Adapting Ophthalmology Practices in Puerto Rico During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleHailu, Surafuale, Andrea N. Ponce, Juliana Charak, Hiram Jimenez, and Luma Al-Attar. 2025. "Adapting Ophthalmology Practices in Puerto Rico During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study" Epidemiologia 6, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030042

APA StyleHailu, S., Ponce, A. N., Charak, J., Jimenez, H., & Al-Attar, L. (2025). Adapting Ophthalmology Practices in Puerto Rico During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Epidemiologia, 6(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6030042