A Dual-Horizon Peridynamics–Discrete Element Method Framework for Efficient Short-Range Contact Mechanics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Discrete Element Method

- Update position to and the velocity/angular velocity to by

- Compute the force and acceleration at .

- Update the velocity and angular velocity to :

2.1.1. Contact Parameters and Calibration

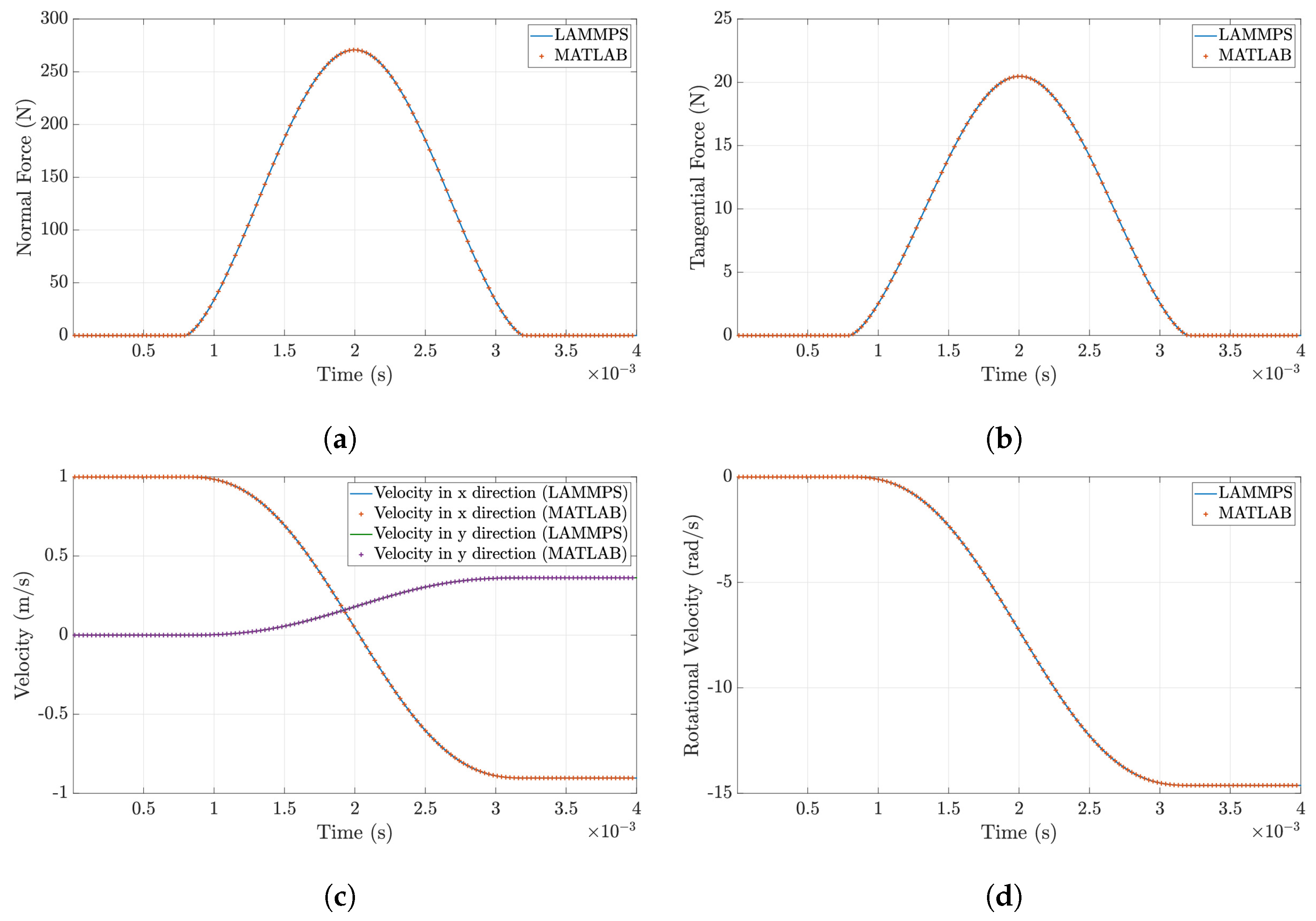

2.1.2. DEM Validation

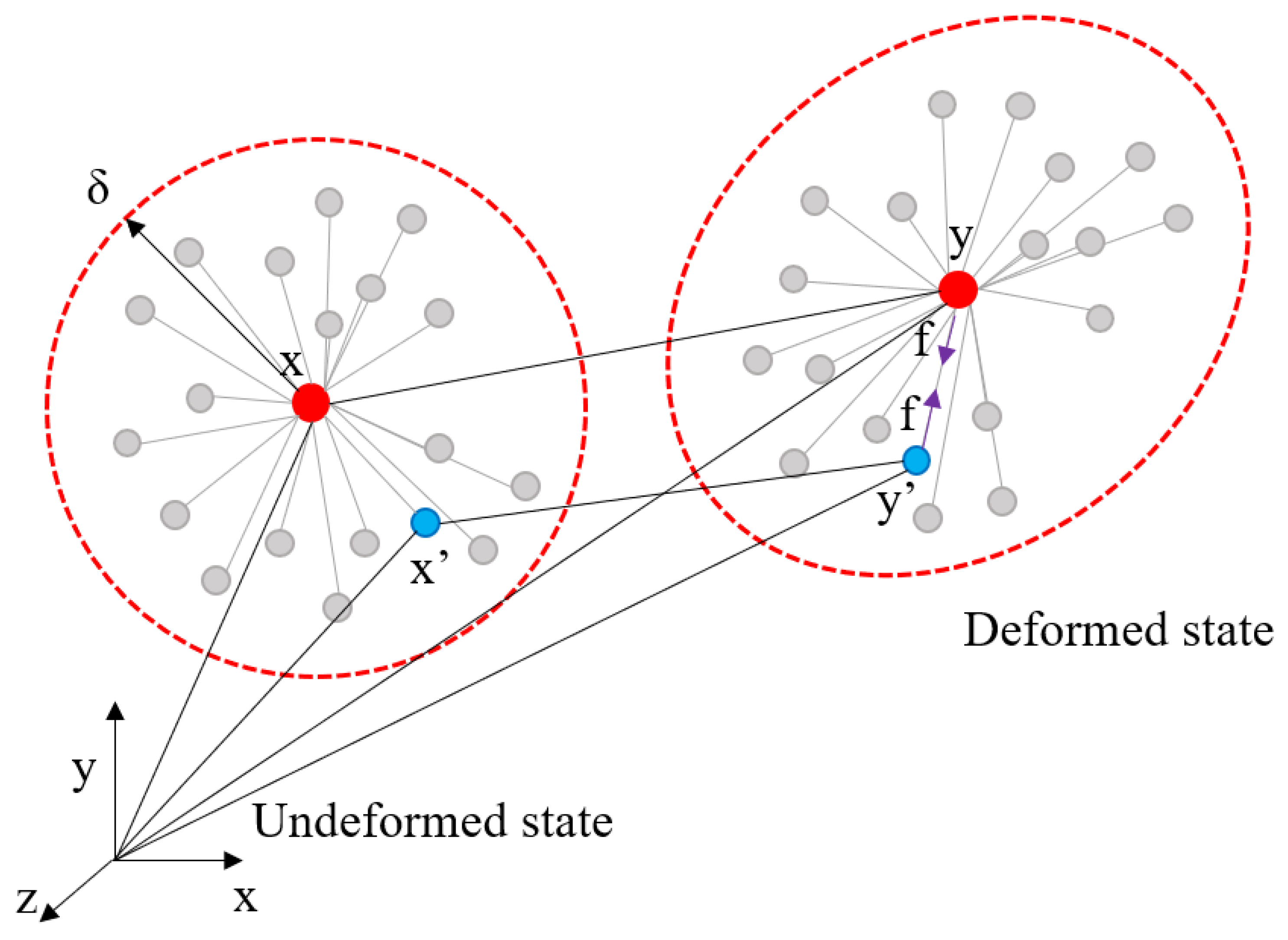

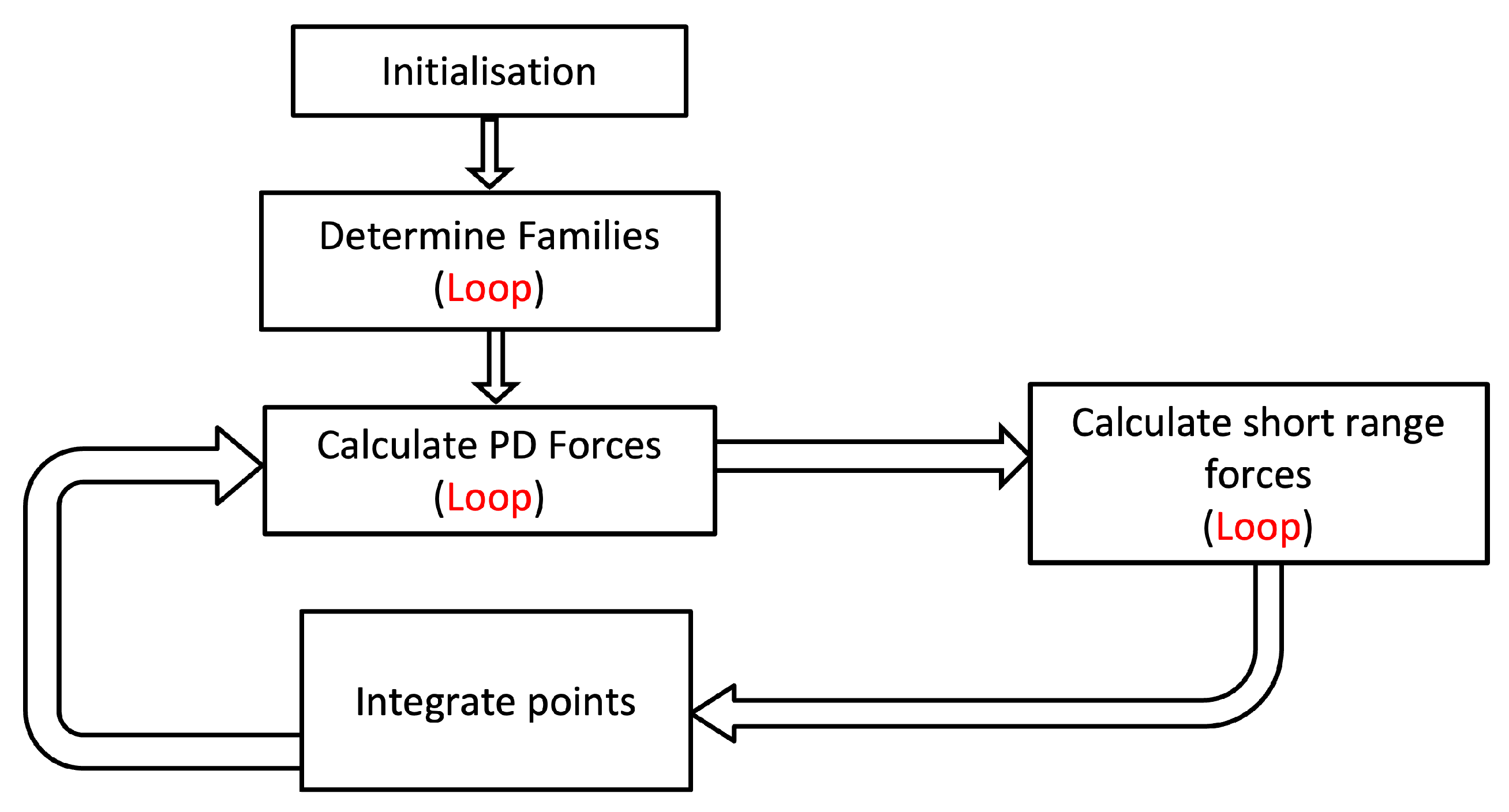

2.2. Peridynamics

2.2.1. Bond-Based Peridynamics

2.2.2. Critical Stretch and Damage

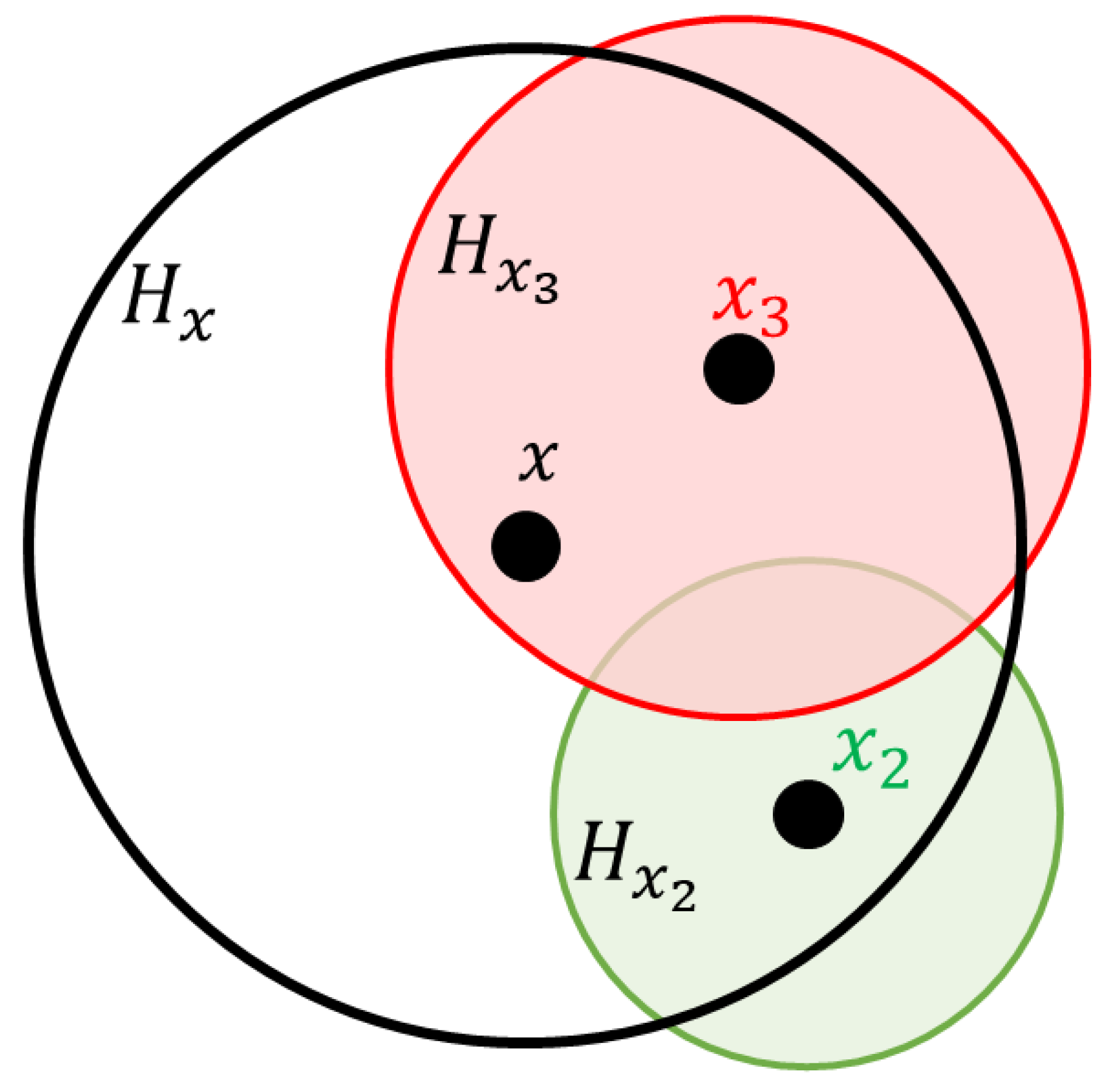

2.2.3. Dual-Horizon Peridynamics

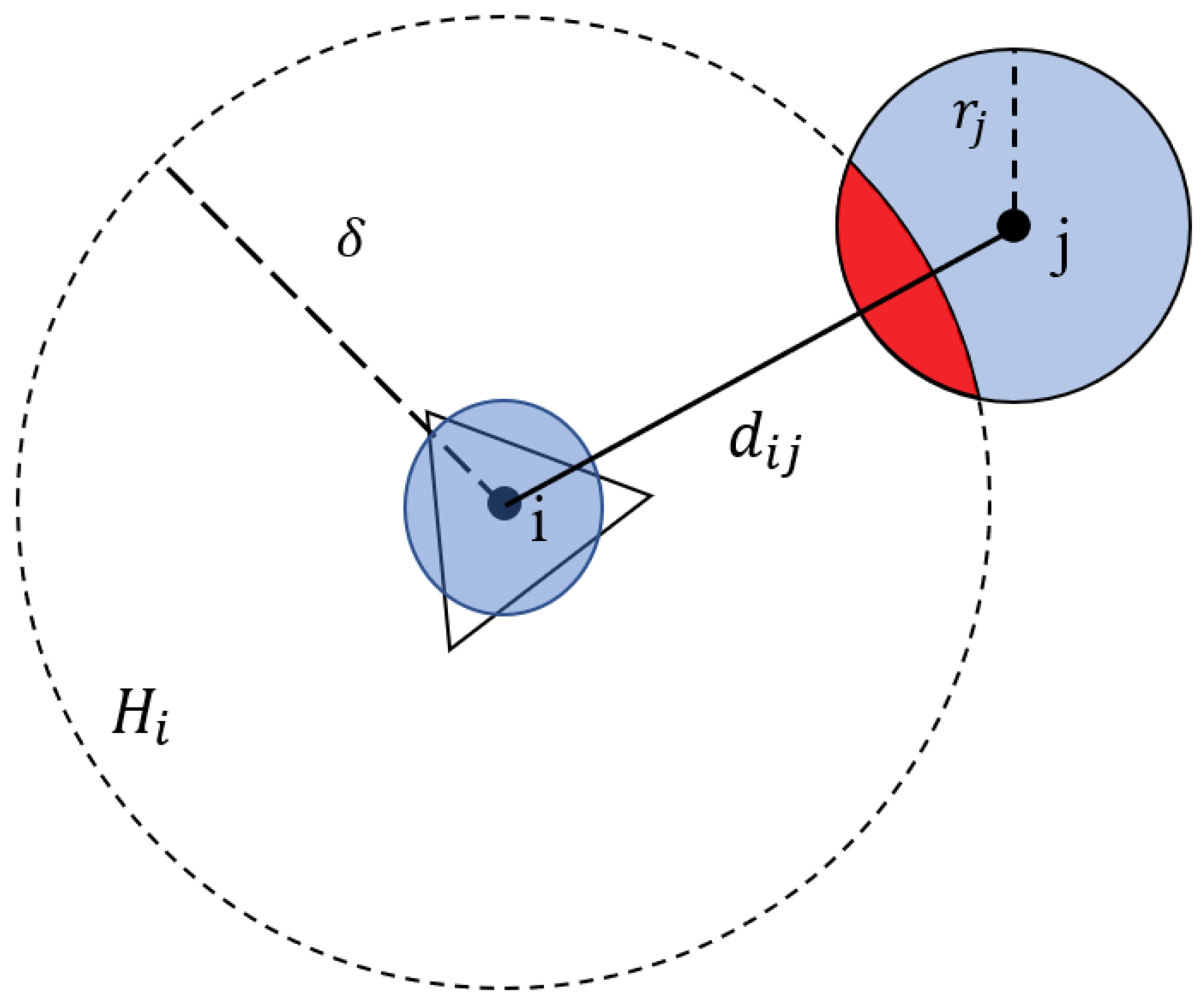

2.2.4. Volume Correction

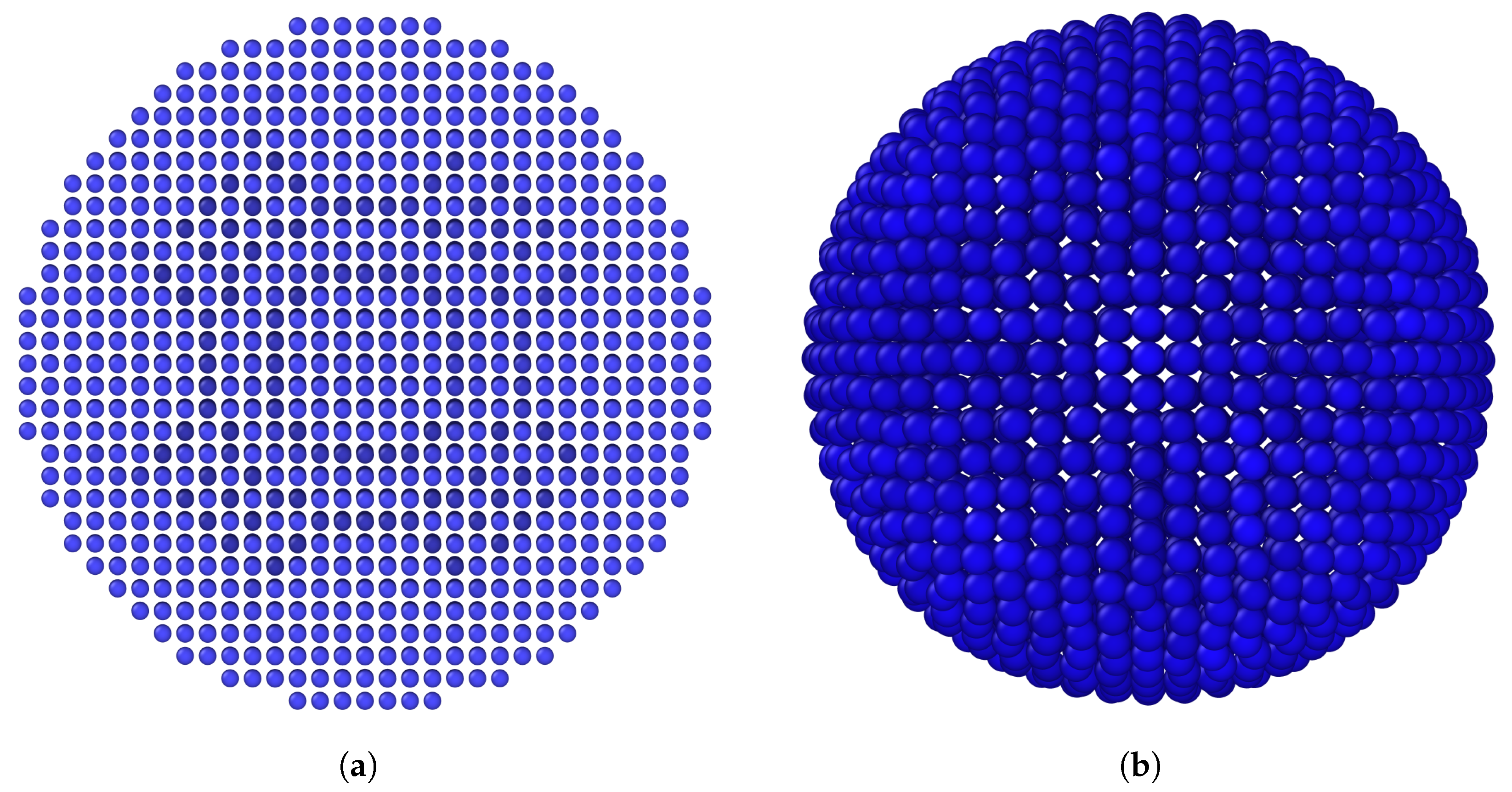

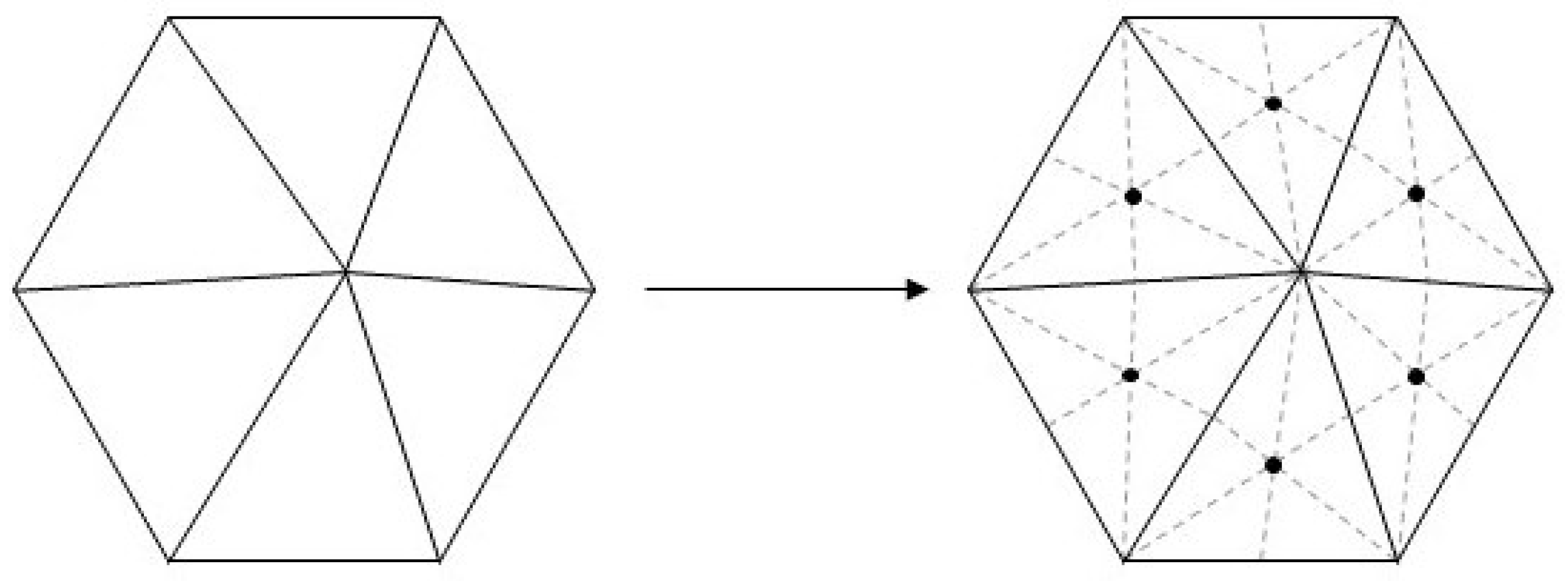

2.2.5. DHPD Discretization

2.2.6. Horizon Selection

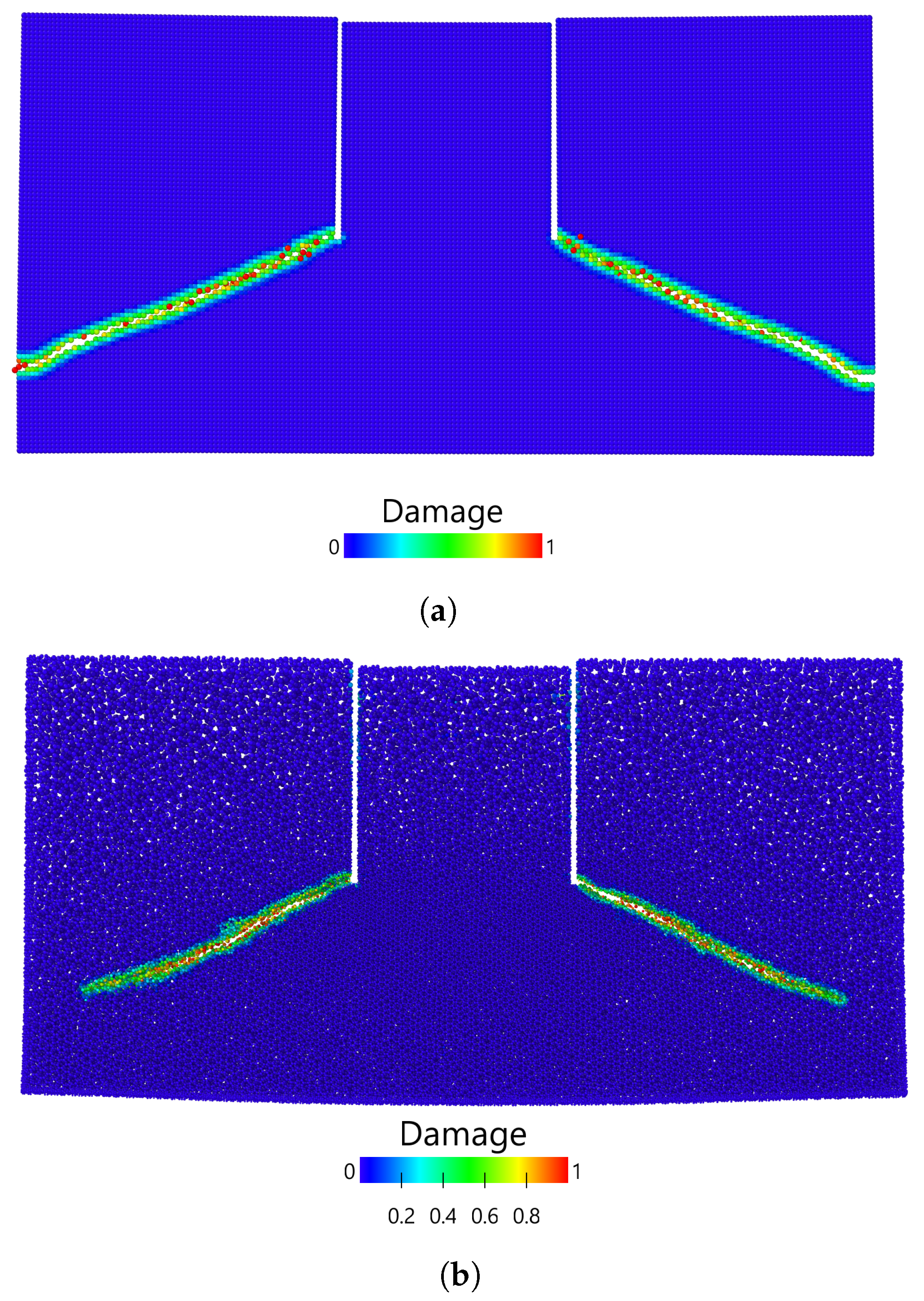

2.2.7. DHPD Validation

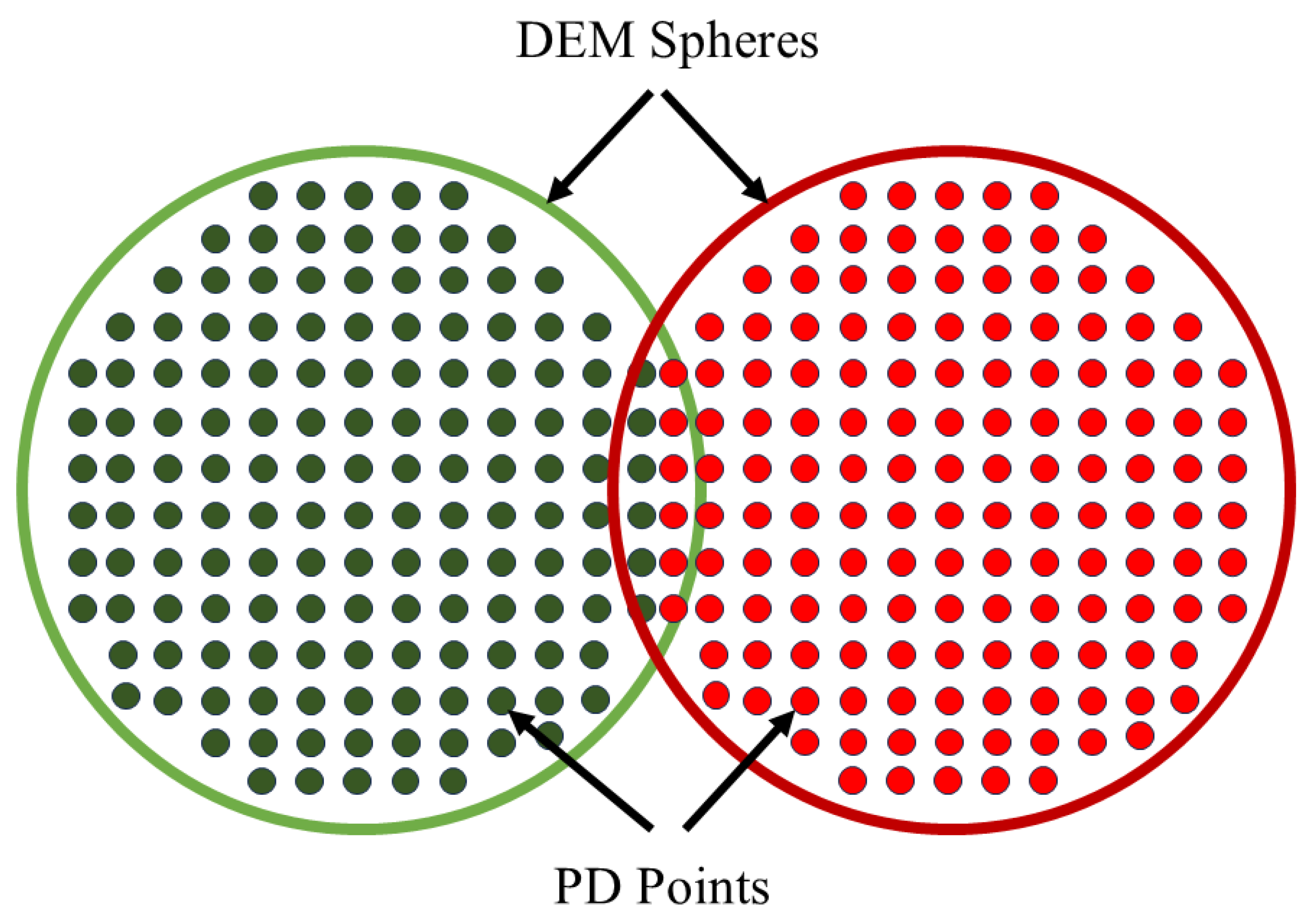

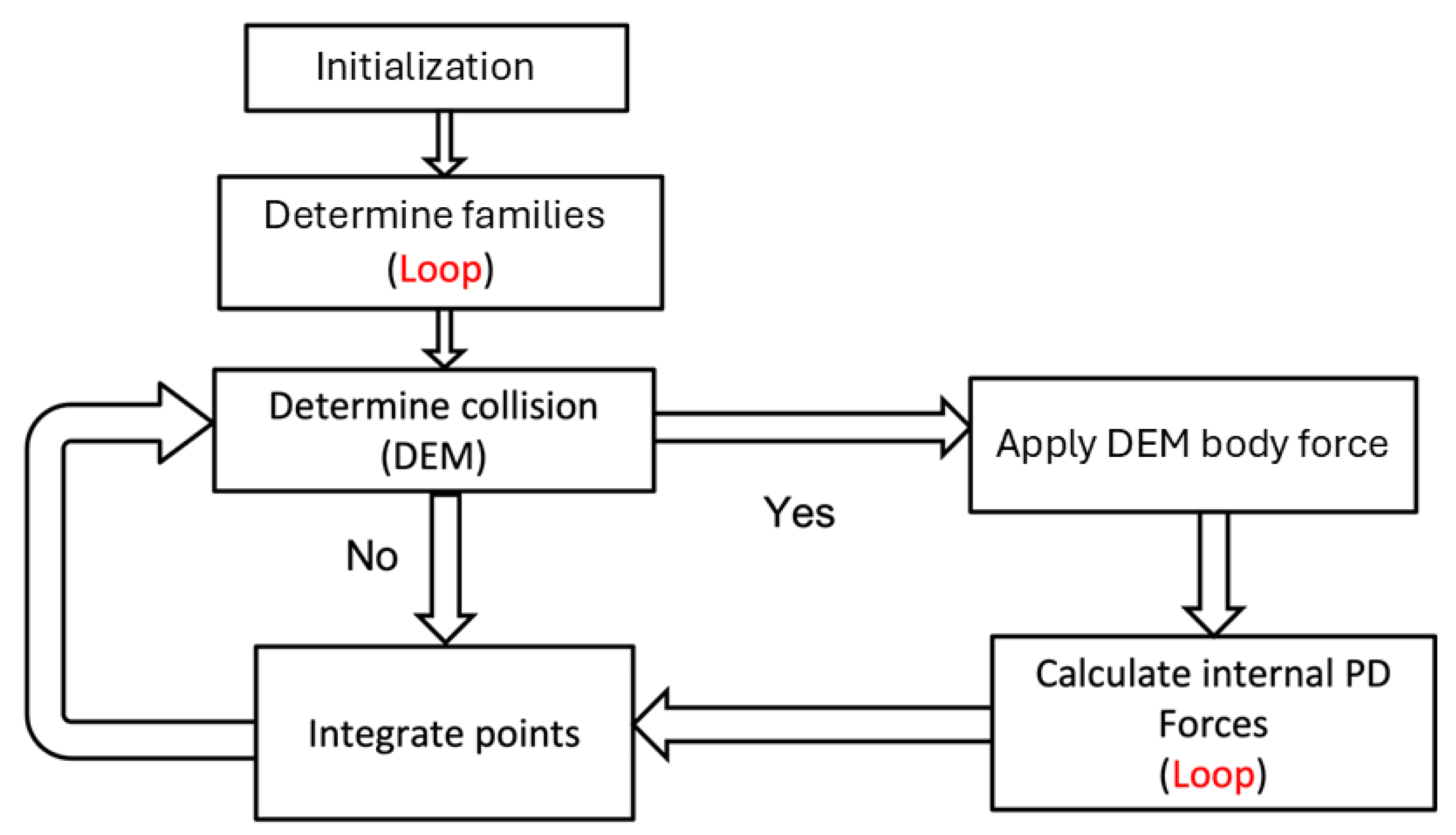

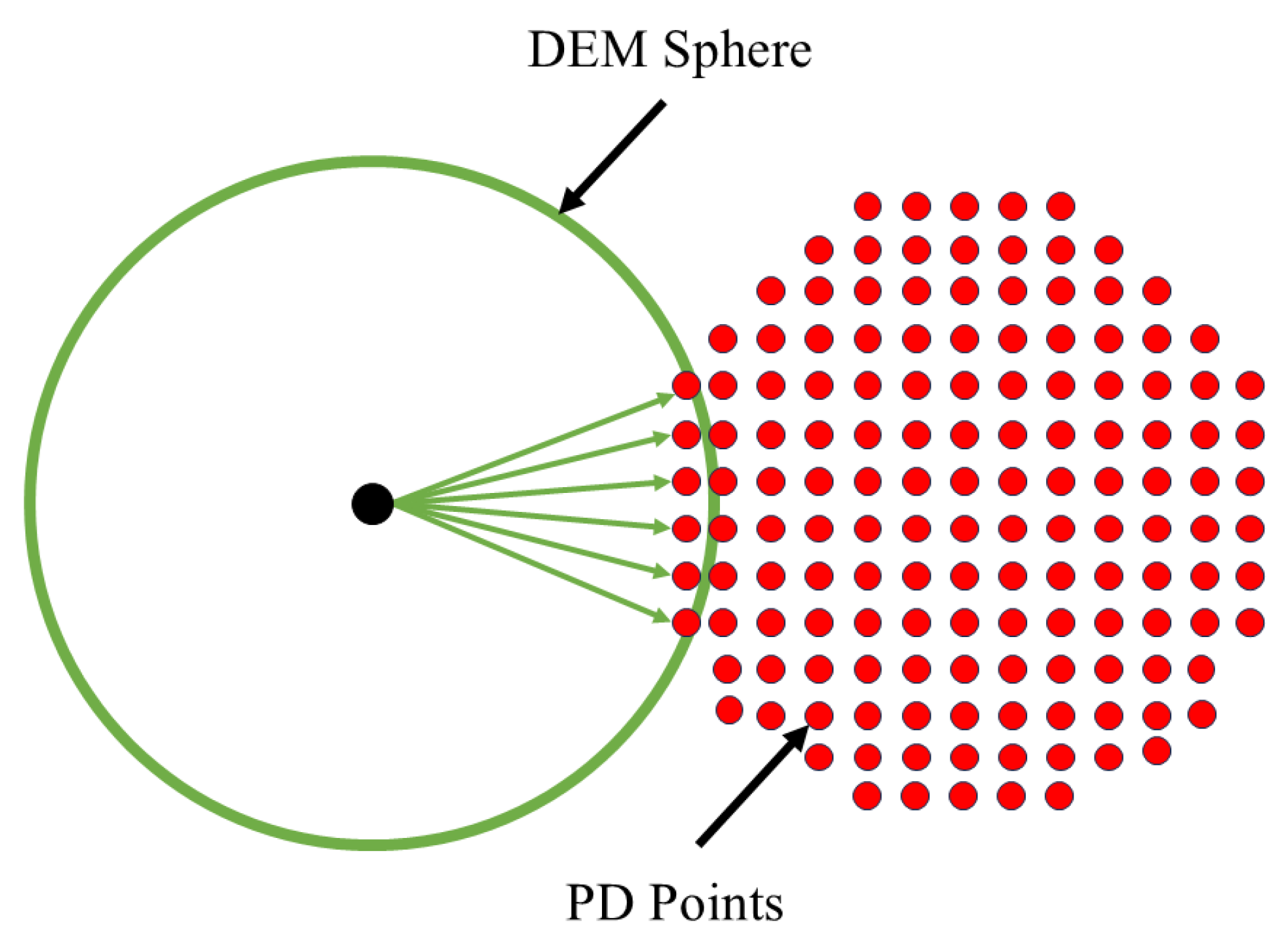

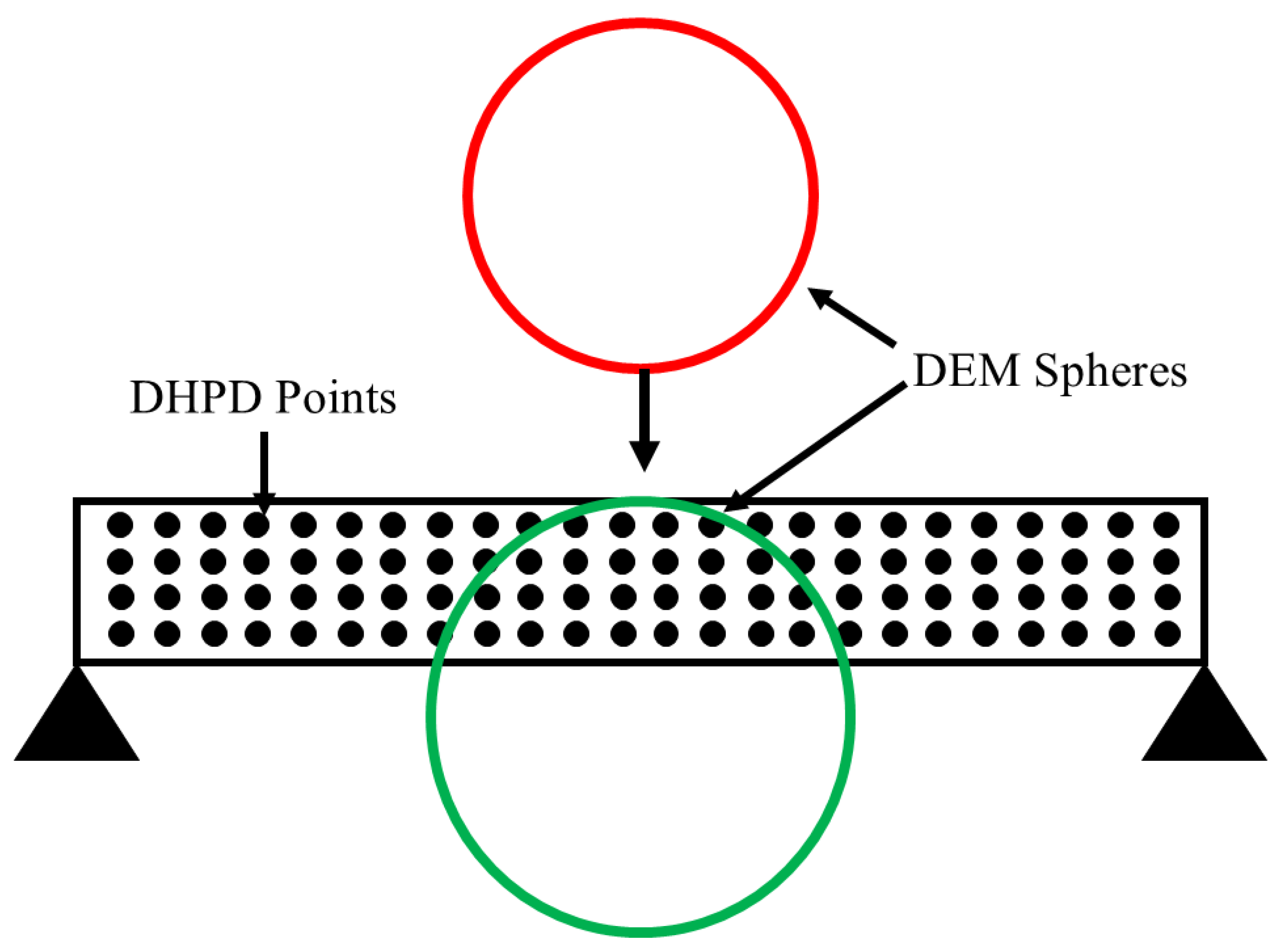

2.2.8. DHPD-DEM Coupling

2.2.9. Distribution of Force

3. Case Studies

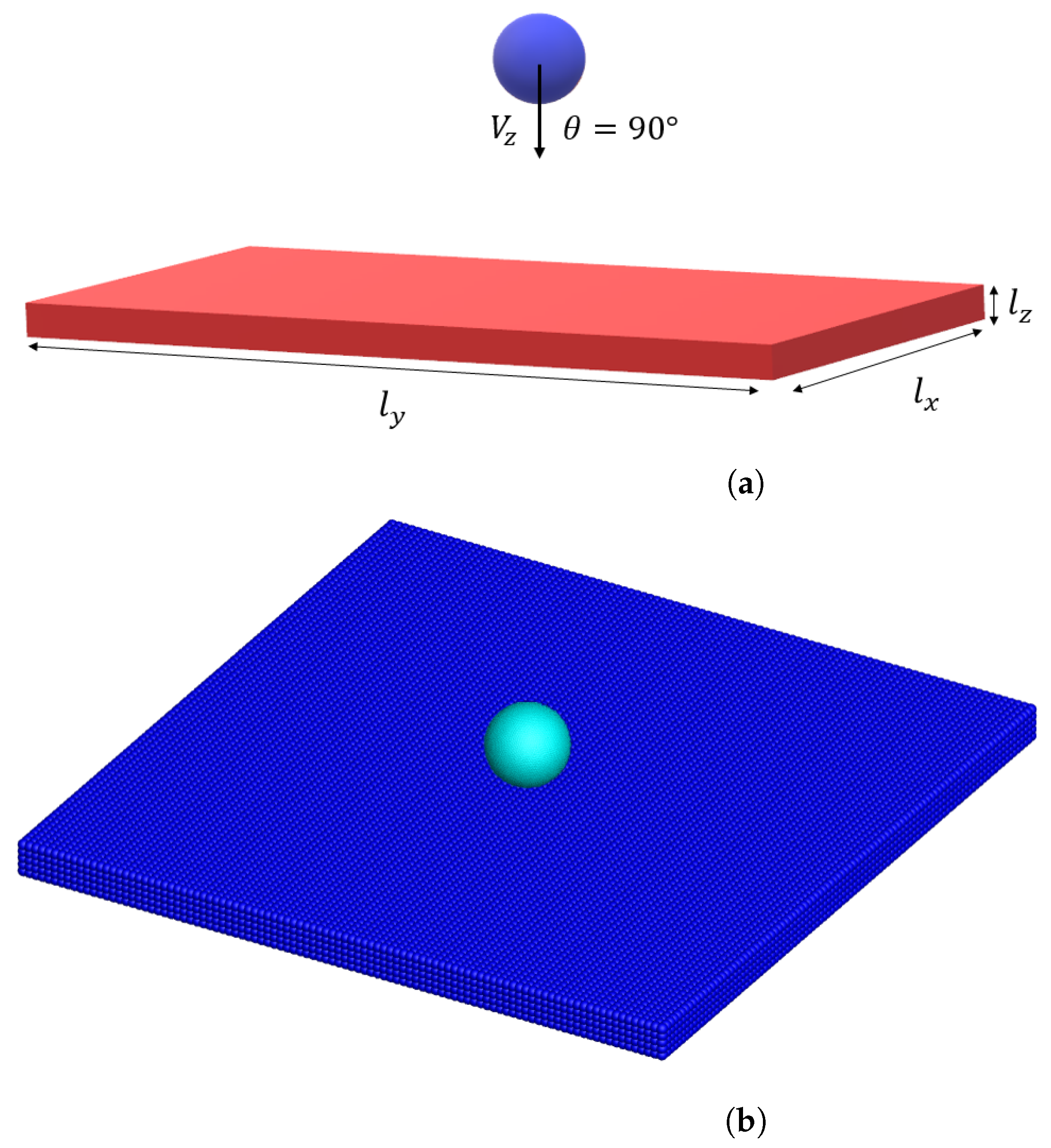

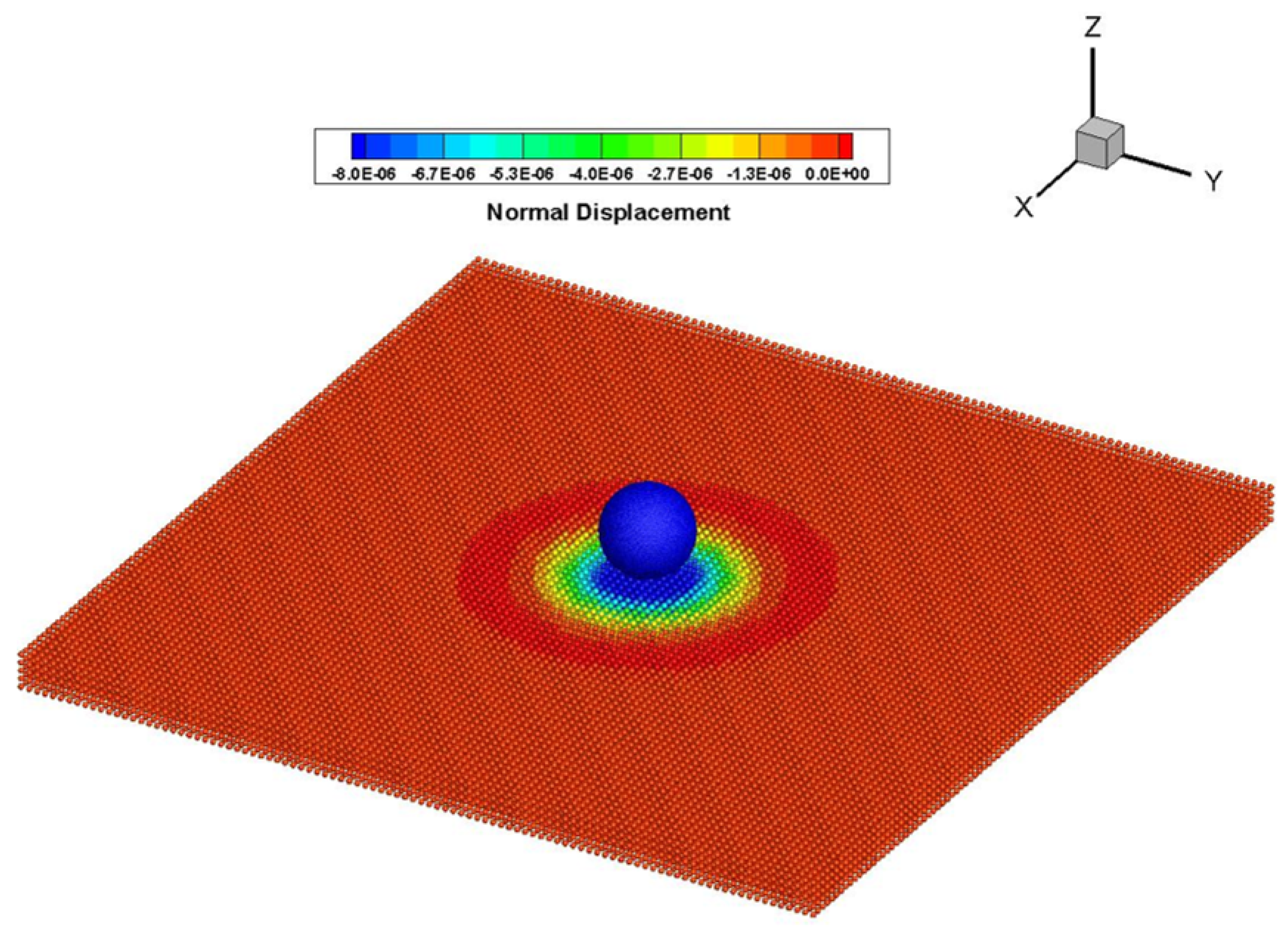

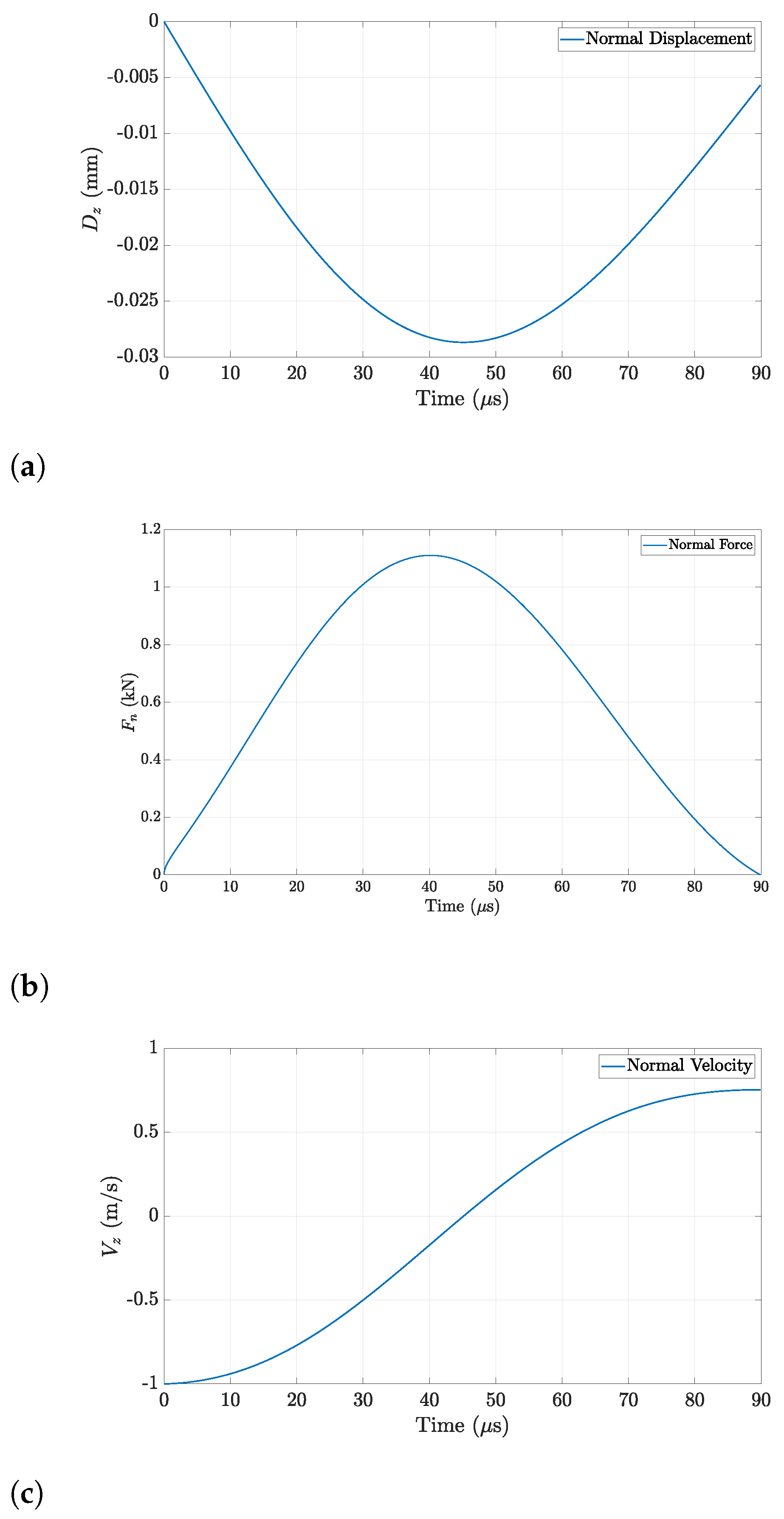

- Case Study 1 investigates the impact of a rigid sphere on a simply supported elastic plate. This case serves as a benchmark to validate the fidelity of force transfer from the DEM to DHPD, by comparing key response metrics (e.g., peak force, displacement, rebound velocity) against analytical solutions and the previous literature.

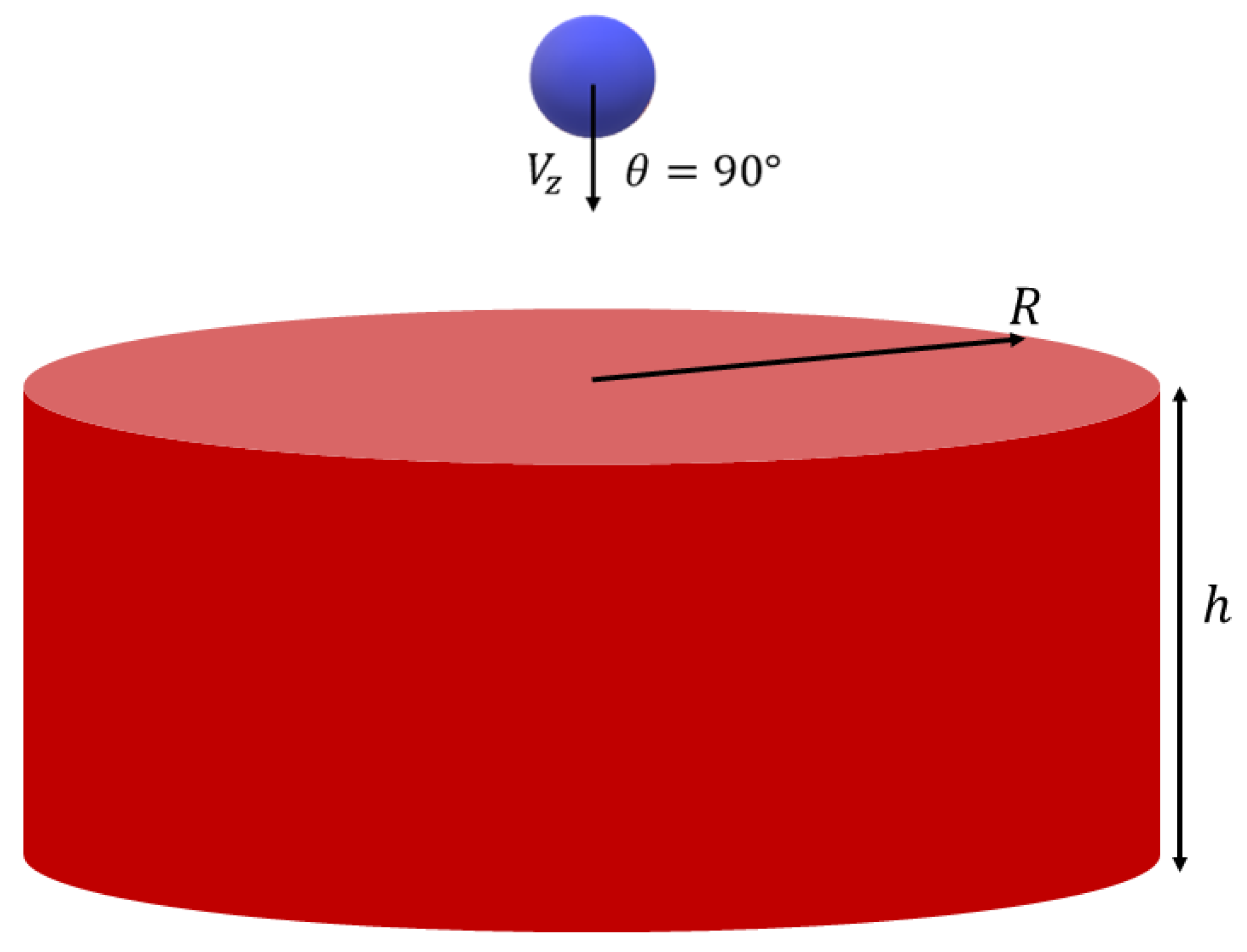

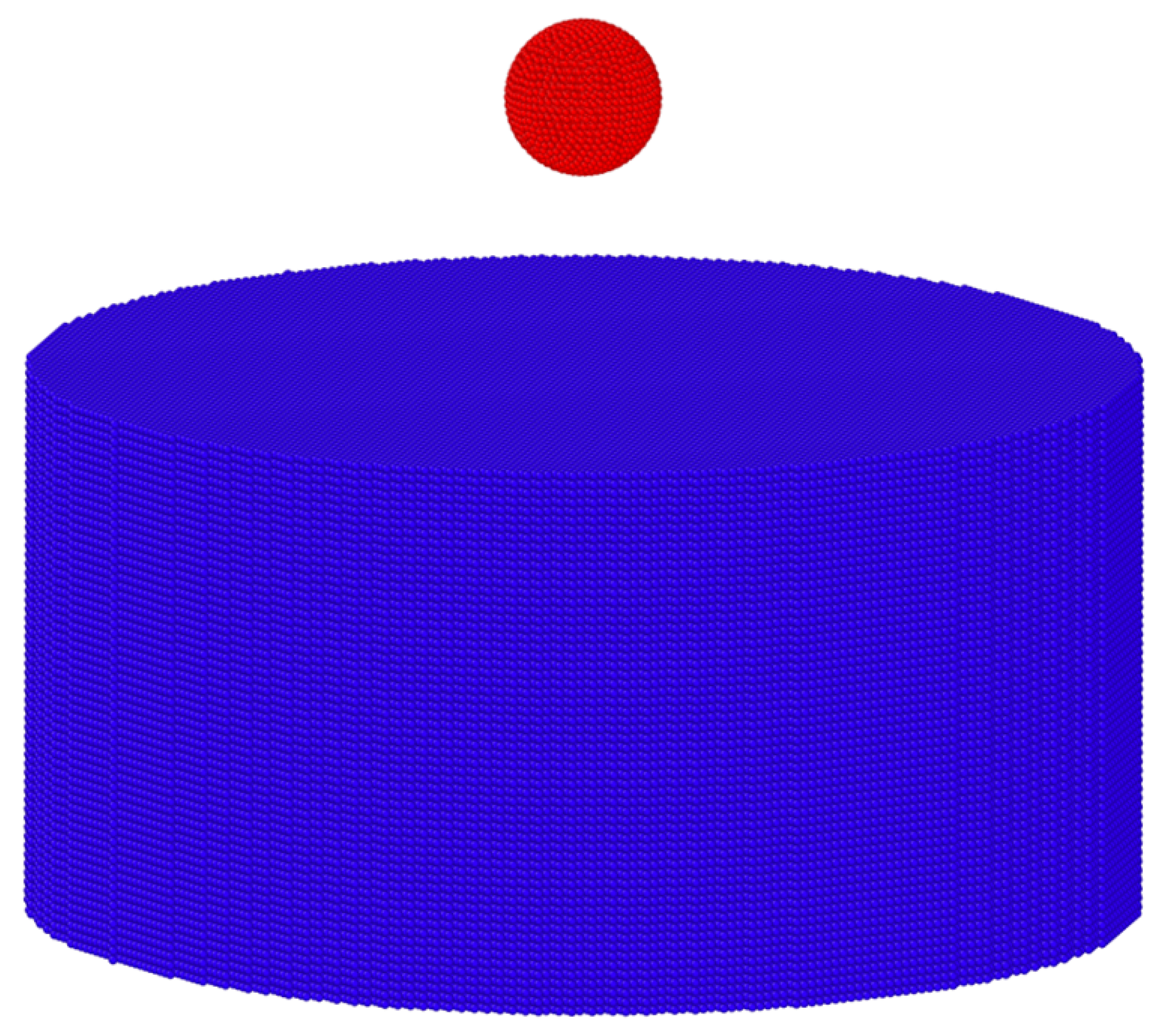

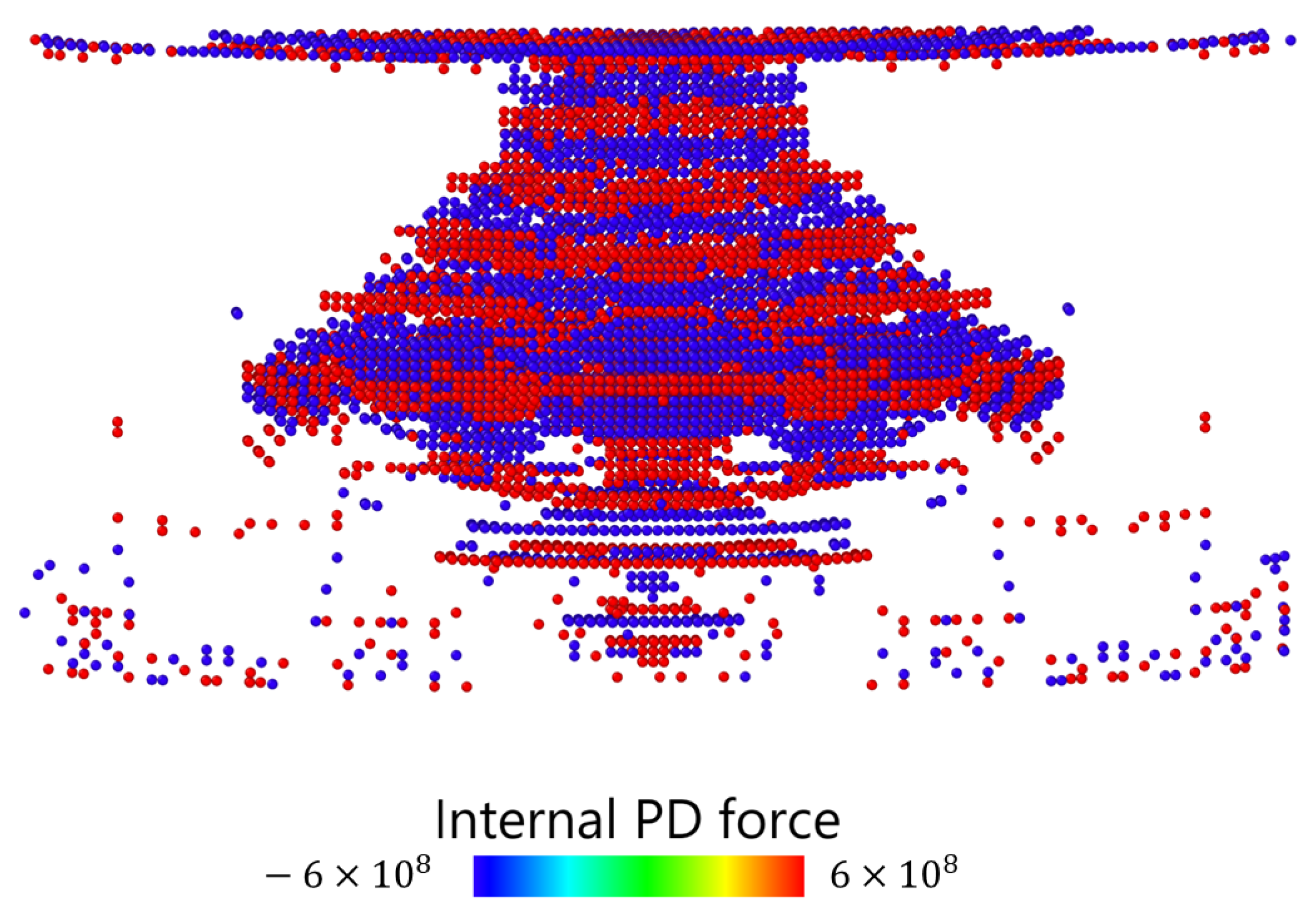

- Case Study 2 examines the high-speed impact of a steel sphere on a brittle cylindrical plate. The purpose of this case is not to capture damage or fracture (which will be added in future work), but to illustrate the directionality and localization of internal PD forces resulting from DEM contact. Qualitative alignment with observed Hertzian cone damage in experiments will be evaluated.

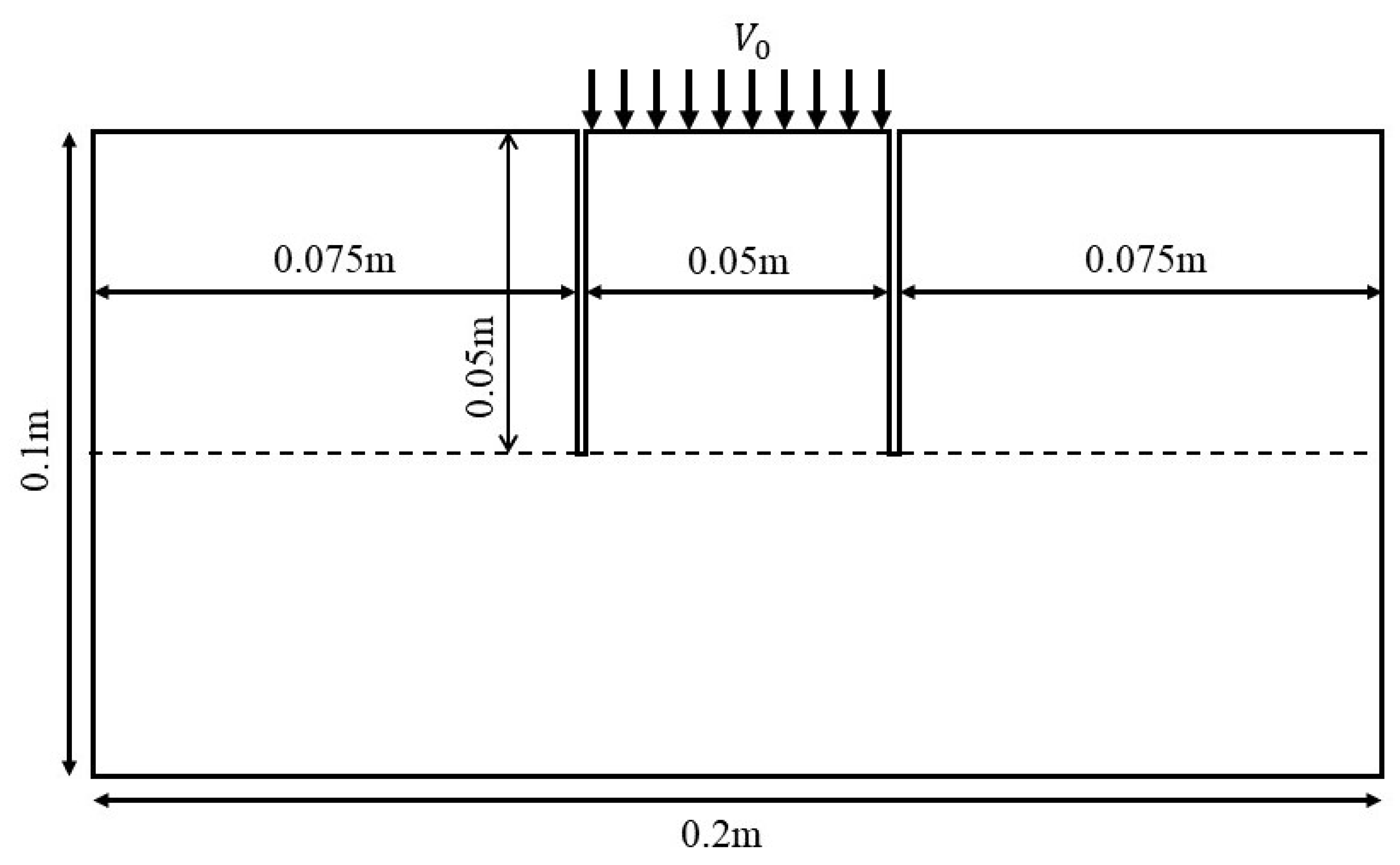

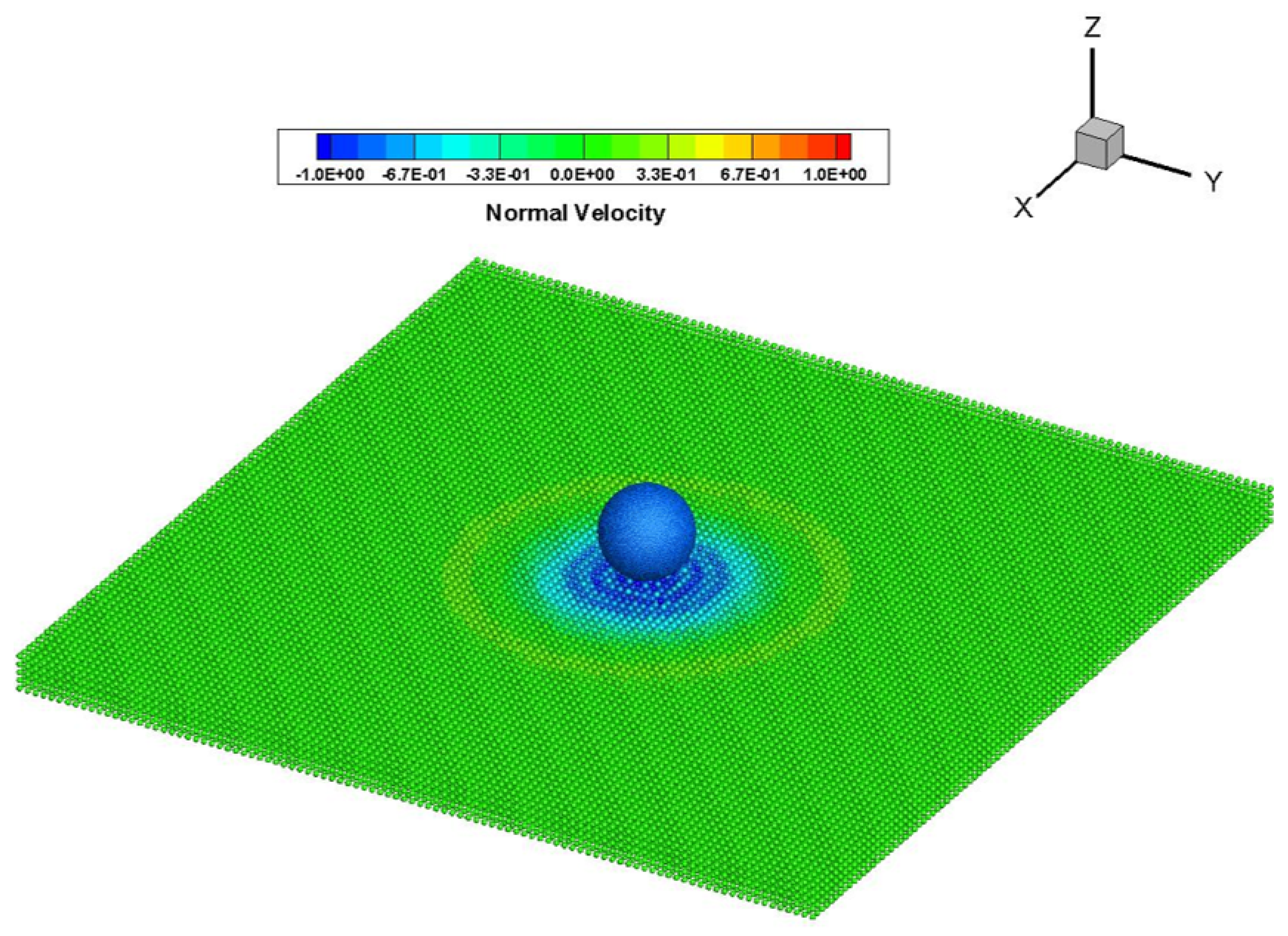

3.1. Normal Impact on a Simply Supported Plate

3.2. Qualitative Demonstration: High-Speed Impact of a Steel Sphere on a Brittle Cylindrical Plate

3.3. Discussion

3.3.1. Contact Check Efficiency

3.3.2. Accuracy of Results

4. Conclusions

- It preserves essential features of contact mechanics with dramatically reduced computational effort;

- It enables realistic internal stress wave propagation in DHPD from externally applied contact forces;

- It lays the groundwork for fully resolved peridynamic fragmentation and erosion modeling using minimal contact infrastructure.

4.1. Future Work

4.2. Operator Choice for PD

4.3. Relation to Filippov Formulations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bezem, K. Computational Modelling of Solid Particle Impact: With Application to Wind Turbine Blades. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oterkus, E.; Madenci, E. Peridynamics for Failure Prediction in Composites. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference 20th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference 14th AIAA, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 April 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 1979, 29, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horabik, J.; Molenda, M. Parameters and contact models for DEM simulations of agricultural granular materials: A review. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 147, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, N.; Zhang, Y.; Haeri, S. Contact models for the multi-sphere discrete element method. Powder Technol. 2023, 416, 118209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.F.; Dong, K.J.; Yu, A.B. DEM study of the flow of cohesive particles in a screw feeder. Powder Technol. 2014, 256, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurentie, J.C.; Traoré, P.; Dascalescu, L. Discrete element modeling of triboelectric charging of insulating materials in vibrated granular beds. J. Electrost. 2013, 71, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.S. Discrete-element modeling of particulate aerosol flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2009, 228, 1541–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunazawa, Y.; Fujihashi, D.; Fukui, S.; Sakai, M.; Tokoro, C. Contact force model including the liquid-bridge force for wet-particle simulation using the discrete element method. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, S.; Wang, Y.; Ghita, O.; Sun, J. Discrete element simulation and experimental study of powder spreading process in additive manufacturing. Powder Technol. 2017, 306, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, S. Optimisation of blade type spreaders for powder bed preparation in Additive Manufacturing using DEM simulations. Powder Technol. 2017, 321, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajepor, S.; Ejtehadi, O.; Haeri, S. The effects of interstitial inert gas on the spreading of Inconel 718 in powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 75, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.R.; am Ende, M.T.; Hancock, B.C. Process Modeling in the Pharmaceutical Industry using the Discrete Element Method. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 442–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O.; Cundall, P.A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 1329–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P. Modelling comminution devices using DEM. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2001, 25, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjiza, A.; Owen, D.R.J.; Bicanic, N. A combined finite-discrete element method in transient dynamics of fracturing solids. Eng. Comput. 1995, 12, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madenci, E.; Oterkus, E. Peridynamic Theory and Its Applications; Number 2; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javili, A.; Morasata, R.; Oterkus, E.; Oterkus, S. Peridynamics review. Math. Mech. Solids 2018, 24, 3714–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A. Reformulation of elasticity theory for discontinuities and long-range forces. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000, 48, 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A.; Epton, M.; Weckner, O.; Xu, J.; Askari, E. Peridynamic States and Constitutive Modeling. J. Elast. 2007, 88, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ha, Y.D.; Bobaru, F. Peridynamic model for dynamic fracture in unidirectional fiber-reinforced composites. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2012, 217–220, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oterkus, E.; Madenci, E.; Weckner, O.; Silling, S.; Bogert, P.; Tessler, A. Combined finite element and peridynamic analyses for predicting failure in a stiffened composite curved panel with a central slot. Compos. Struct. 2012, 94, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Askari, A.; Weckner, O.; Silling, S. Peridynamic analysis of impact damage in composite laminates. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2008, 21, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.D.; Bobaru, F. Characteristics of dynamic brittle fracture captured with peridynamics. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2011, 78, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.D.; Bobaru, F. Studies of dynamic crack propagation and crack branching with peridynamics. Int. J. Fract. 2010, 162, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, B.; Madenci, E. Prediction of crack paths in a quenched glass plate by using peridynamic theory. Int. J. Fract. 2009, 156, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, D.J. A Nonlocal Approach to Modeling Crack Nucleation in AA 7075-T651. In Proceedings of the Volume 8: Mechanics of Solids, Structures and Fluids; Vibration, Acoustics and Wave Propagation, ASMEDC, Denver, CO, USA, 11–17 November 2011; pp. 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A.; Weckner, O.; Askari, E.; Bobaru, F. Crack nucleation in a peridynamic solid. Int. J. Fract. 2010, 162, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobaru, F.; Ha, Y.; Hu, W. Damage progression from impact in layered glass modeled with peridynamics. Open Eng. 2012, 2, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A.; Askari, E. A meshfree method based on the peridynamic model of solid mechanics. Comput. Struct. 2005, 83, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupek, M.R.; Rimoli, J.J.; Radovitzky, R. An approach for incorporating classical continuum damage models in state-based peridynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2013, 263, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleson, P.; Parks, M. On the Role of the Influence Function in the Peridynamic Theory. Int. J. Multiscale Comput. Eng. 2011, 9, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, E.; Bobaru, F.; Lehoucq, R.B.; Parks, M.L.; Silling, S.A.; Weckner, O. Peridynamics for multiscale materials modeling. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 125, 12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghajari, M.; Iannucci, L.; Curtis, P. A peridynamic material model for the analysis of dynamic crack propagation in orthotropic media. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2014, 276, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sundararaghavan, V. A peridynamic implementation of crystal plasticity. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2014, 51, 3350–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstle, W.; Sau, N.; Silling, S. Peridynamic modeling of concrete structures. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2007, 237, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Ren, B.; Fan, H.; Li, S.; Wu, C.T.; Regueiro, R.A.; Liu, L. Peridynamics simulations of geomaterial fragmentation by impulse loads. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2015, 39, 1304–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, D.J. Simulation of Dynamic Fracture Using Peridynamics, Finite Element Modeling, and Contact. In Proceedings of the Volume 9: Mechanics of Solids, Structures and Fluids, ASMEDC, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–18 November 2010; pp. 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleson, P.; Littlewood, D.J. Convergence studies in meshfree peridynamic simulations. Comput. Math. Appl. 2016, 71, 2432–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Haeri, S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Pan, G. A coupled peridynamics and DEM-IB-CLBM method for sand erosion prediction in a viscous fluid. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on Computational Mechanics (ECCM 6) 7th European Conference on Computational Fluid Dynamics (ECFD 7), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Haeri, S. A multi-physics peridynamics-DEM-IB-CLBM framework for the prediction of erosive impact of solid particles in viscous fluids. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 352, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Desai, P.S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Lipton, R. Peridynamics-based discrete element method (PeriDEM) model of granular systems involving breakage of arbitrarily shaped particles. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2021, 151, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.D.; West, B.A.; Frisch, N.J.; O’Connor, D.T.; Parno, M.D. ParticLS: Object-oriented software for discrete element methods and peridynamics. Comput. Part. Mech. 2022, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Thoeni, K.; Rojek, J. A generalised multi-scale Peridynamics–DEM framework and its application to rigid–soft particle mixtures. Comput. Mech. 2023, 71, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, K.; Haeri, S.; Iqbal, I.; Zhang, Y. Hybrid PD-DEM approach for modeling surface erosion by particles impact. Comput. Part. Mech. 2023, 10, 1895–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, Y.; Ren, H.; Bui, T.Q.; Madenci, E.; Rabczuk, T.; Wei, Y. Dual-horizon peridynamics modeling of coupled chemo-mechanical-damage for interface oxidation-induced cracking in thermal barrier coatings. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 430, 117225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, F.; Feng, R. A multi-horizon peridynamics for coupled fluid flow and heat transfer. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1010, A66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sajal; Roy, P. Peridynamics contact model: Application to healing using phase field theory. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 280, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, P.; Lai, Z.; Yin, Z.Y.; Huang, L.; Xu, C. Machine-learning-enabled discrete element method: The extension to three dimensions and computational issues. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 432, 117445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.; Moradi, M.; Pang, Y.; Schott, D. Adaptive AI-based surrogate modelling via transfer learning for DEM simulation of multi-component segregation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.; Xu, L.; Zheng, J. An erosion model for the discrete element method. Particuology 2017, 34, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luding, S. Introduction to discrete element methods. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2008, 12, 785–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindlin, R.D. Compliance of Elastic Bodies in Contact. J. Appl. Mech. 1949, 16, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Z. Introduction to Materials Modelling; Maney Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; in’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. LAMMPS#x2014;A flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhuang, X.; Cai, Y.; Rabczuk, T. Dual-horizon peridynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2016, 108, 1451–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuzaine, C.; Remacle, J.F. Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2009, 79, 1309–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.A. Dynamic fracture modeling with a meshfree peridynamic code. In Computational Fluid and Solid Mechanics 2003; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, L.; Lam, K.Y. Dynamic response of fully-clamped laminated composite plates subjected to low-velocity impact of a mass. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1998, 35, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicode, V.; Diyaroglu, C.; Madenci, E. Peridynamic Modeling of Damage due to Multiple Sand Particle Impacts in the Presence of Contact and Friction. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicode, S.V.K.; Madenci, E. Contact analysis of rigid and deformable bodies with peridynamics. In Peridynamic Modeling, Numerical Techniques, and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhri, M.M. Dynamic fracture of inorganic glasses by hard spherical and conical projectiles. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 373, 20140135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirtich, B.V. Impulse-Based Dynamic Simulation of Rigid Body Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.R.; O’Connor, R. A linear complexity intersection algorithm for discrete element simulation of arbitrary geometries. Eng. Comput. 1995, 12, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Ding, Y.; Miao, Q.; Sang, G.; Jia, M. An improved contact detection algorithm for bonded particles based on multi-level grid and bounding box in DEM simulation. Powder Technol. 2020, 374, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madenci, E.; Barut, A.; Futch, M. Peridynamic differential operator and its applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 304, 408–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, A.F. Differential Equations with Discontinuous Righthand Sides; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieci, L.; Lopez, L. Sliding Motion in Filippov Differential Systems: Theoretical Results and a Computational Approach. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2009, 47, 2023–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.; Montijano, J.I.; Rández, L. Algorithm 968. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2017, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter | 0.05 m |

| Young’s Modulus | Pa |

| Density | 2800 kg/m3 |

| Mass | 0.1833 kg |

| Velocity Vector | [1, 0, 0], [−1, 0, 0] m/s |

| Static Yield Criterion | 0.5 |

| Timestep | s |

| Object | Parameters | DHPD/DEM | Anicode and Madenci [61] | Chun and Lam [59] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impactor | Dz,max (mm) | 0.00287 | 0.0027 | 0.0025 |

| Vz,max | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Fn,max (kN) | 1.11 | 1.2335 | 1.25 | |

| Plate | Dz,max (mm) | 0.008 | 0.00781 | 0.0078 |

| Property | Sphere | Plate |

|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus E (GPa) | 205 | 22.35 |

| Poisson’s Ratio v | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 7945 | 2200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bezem, K.; Haeri, S.; TerMaath, S. A Dual-Horizon Peridynamics–Discrete Element Method Framework for Efficient Short-Range Contact Mechanics. Modelling 2025, 6, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040131

Bezem K, Haeri S, TerMaath S. A Dual-Horizon Peridynamics–Discrete Element Method Framework for Efficient Short-Range Contact Mechanics. Modelling. 2025; 6(4):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040131

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezem, Kinan, Sina Haeri, and Stephanie TerMaath. 2025. "A Dual-Horizon Peridynamics–Discrete Element Method Framework for Efficient Short-Range Contact Mechanics" Modelling 6, no. 4: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040131

APA StyleBezem, K., Haeri, S., & TerMaath, S. (2025). A Dual-Horizon Peridynamics–Discrete Element Method Framework for Efficient Short-Range Contact Mechanics. Modelling, 6(4), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040131