Abstract

Personality changes have been reported following organ transplantation. Most commonly, such changes have been described among heart transplant recipients. We set out to examine whether personality changes occur following organ transplantation, and specifically, what types of changes occur among heart transplant recipients compared to other organ recipients. A cross-sectional study was conducted in which 47 participants (23 heart recipients and 24 other organ recipients) completed an online survey. In this study, 89% of all transplant recipients reported personality changes after undergoing transplant surgery, which was similar for heart and other organ recipients. The only personality change that differed between heart and other organ recipients and that achieved statistical significance was a change in physical attributes. Differences in other types of personality changes were observed between these groups but the number of participants in each group was too small to achieve statistical significance. Overall, the similarities between the two groups suggest heart transplant recipients may not be unique in their experience of personality changes following transplantation, but instead such changes may occur following the transplantation of any organ. With the exception of physical attributes, the types of personality changes reported were similar between the two groups. These finding indicate that heart transplant recipients are not unique in their reported experience of personality changes following organ transplantation. Further studies are needed to deepen our understanding of what causes these personality changes.

Keywords:

personality change; organ transplant; heart transplant; temperament; emotions; preferences 1. Introduction

More than 144,000 organs were transplanted worldwide in 2021 [1] and just under 8200 heart transplants were performed worldwide in 2020 [2]. Undergoing transplantation surgery can have significant psychological effects and some recipients worry about developing the personality traits of their donor [3]. This concern has been supported by studies that describe heart transplant recipients experiencing changes in their personality after receiving a new organ, with some experiencing traits that were present in their donor [4]. Such reports have appeared in both the medical and lay literature.

Personality changes following transplant surgery are not limited to heart transplantation. Pearsall reported changes in personality following the transplantation of kidney, liver, and other organs, but described these changes as generally transitory. He suggested personality changes following heart transplantation appear to be more robust and more strongly associated with the donor’s history than personality changes reported following the transplantation of other organs [4].

While multiple accounts exist of personality changes following organ transplants, there is a paucity of scientific literature quantifying such changes. We set out to explore whether individuals who underwent organ transplantation experienced personality changes, and if so, what were these changes, and were these changes similar or different in individuals who underwent heart versus other organ transplantation.

1.1. How Common Are Personality Changes Following Organ Transplantation?

Previous studies have described personality changes following organ transplantation in some but not all recipients.

A Swedish study looked at personality changes in 35 heart and kidney transplant recipients for two years following their surgery. This study found some recipients reported personality changes following transplant surgery, but the frequency of these changes was not quantified [5].

A Canadian study examined 27 adolescent heart transplant recipients and found these individuals struggled to integrate their concepts of “self” and “other” (i.e., their donated organ) and several recipients experienced thoughts or questions about potentially acquiring characteristics of their donor via their donor’s heart. However, no statistics were given for the frequency of personality changes [3].

An Austrian study reported on the frequency of personality changes following heart transplantation. These investigators examined 47 heart transplant recipients approximately 3 months after transplant surgery. They found 21% of recipients described changes in their personality after receiving a new heart whereas 79% reported no such changes [6].

A U.S. study explored psychiatric outcomes in 41 adults and 2 children who had undergone heart transplantation. This study found 68% of adults experienced affective disorders, 45% sexual dysfunction, 37% organic brain syndromes, and 25% family or marital problems. The investigators attributed many of the problems to the immunosuppressive drugs that were administered post-transplant to prevent the rejection of the new heart [7].

1.2. Types of Personality Changes Following Transplant

Many different types of personality changes have been described following organ transplantation. These include changes in preferences for food, music, art, sex, recreation, and career [8], the experience of new memories [9], feelings of euphoria, enhanced social and sexual adaptation [10], improved cognitive abilities [11], and spiritual or religious episodes [12]. These changes were generally described as neutral or positive. However, troubling changes have also been reported. As many as 30–50% percent of heart transplant recipients experience emotional or affective issues [7,13], while others experience delirium [10], depression, anxiety [14,15,16], psychosis [17], and sexual dysfunction [18].

A report in the lay literature describes the case of Claire Sylvia who reported changes in her personality, preferences, and behaviors following a heart and lung transplant at Yale-New Haven hospital in 1988. Following surgery, Sylvia developed a new taste for green peppers and chicken nuggets, foods she previously disliked. As soon as she was released from the hospital, she promptly headed to a Kentucky Fried Chicken to order chicken nuggets. She later met her donor’s family and inquired about his affinity for green peppers. Their response was, “Are you kidding? He loved them… But what he really loved was chicken nuggets” (p. 184, [9]). Sylvia later discovered that at the time of her donor’s death in a motorcycle accident, a container of chicken nuggets was found under his jacket [9].

In addition to changes in preferences, some recipients describe new aversions after receiving a donor heart. For example, a 5-year-old boy received the heart of a 3-year-old boy but was not informed about his donor’s age or cause of death. Despite this lack of information, he provided a vivid description of his donor after the surgery: “He’s just a little kid. He’s a little brother like about half my age. He got hurt bad when he fell down. He likes Power Rangers a lot I think, just like I used to. I don’t like them anymore though” (p. 70, [8]). Subsequently it was reported that his donor had died after falling from an apartment window while trying to reach a Power Ranger toy that had fallen onto the window ledge. After receiving his new heart, the recipient refused to touch or play with Power Rangers [8].

Some recipients have reported “memories” that seem unrelated to their own lived experiences and involved sensory experiences that were, unbeknownst to them, related to their donor. For example, a 56-year-old college professor received the heart of a 34-year-old police officer who tragically lost his life after he was fatally shot in the face. Following the transplant, the recipient reported a peculiar experience, stating, “A few weeks after I got my heart, I began to have dreams. I would see a flash of light right in my face and my face gets real, real hot. It actually burns” (p. 71, [8]).

1.3. Proposed Causes of Changes Following Organ Transplant

Numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain changes in personality following organ transplantation. These hypotheses can be grouped into three categories: psychological, biochemical, and electrical/energetic.

Psychological hypotheses include the idea that the personality profiles of patients influence the outcomes of organ transplantation [9]. For example, personality changes have been suggested to result from fantasies about the donor and the donor’s organ [4]. Personality changes have also been hypothesized to result from the recipients’ use of defense mechanisms which are employed to manage the stress associated with transplant surgery [4,8,9]. Magical thinking and analogy thinking have also been offered as explanations for the personality changes that may occur following transplant. The latter is described as a type of thinking that is based on the idea that since a mixed substance shows traits from all the components that comprise that substance, one could expect the same could occur following transplantation where people view themselves as a mix of their own body and the organ of the donor [5].

Biochemical hypotheses include the concept that the donor’s organ is capable of storing memories or other personality traits that are transferred to the recipient with the donated organ. Examples include the idea that engrams are formed in the brain of the donor and these engrams are transferred to the brain of the recipient via exosomes [19]. The transfer of cellular memory between donor and recipients is another hypothesized mechanism [5]. Several different mechanisms of cellular memory have been suggested including: (1) epigenetic memory, (2) DNA memory, (3) RNA memory, and (4) protein memory [20]. Another biochemical mechanism invoked to explain personality changes in heart transplant recipients involves the transfer of personality characteristics via the intracardiac nervous system. The intracardiac nervous system is a complex system of neurons within the heart that is transferred along with the heart during transplant surgery. These neurons use the same chemical neurotransmitters that are found in the cerebral brain to communicate and store information. This complex system of neurons, which has been termed the “heart brain”, is postulated to store memories which could be transferred with the heart during transplantation surgery, thus altering the recipient’s personality [20].

Another hypothesized mechanism involves alterations in the electromagnetic field of the recipient. Pearsall highlighted the fact that “energy and information are the same thing” (p., 5 [4]). One form of energy is electromagnetic energy, and the heart generates the largest electromagnetic field in the body. Information related to the personality of the donor could be stored within the electromagnetic field of the donor’s heart and this information could then be transferred with the heart during transplant surgery, producing a change in the recipient’s personality [4].

1.4. Limitations of Existing Studies

Previous studies investigating personality changes following organ transplantation are limited by a number of factors including a small sample size, lack of comparison groups, subjective assessments, and a lack of prospective studies. Currently, a paucity of information exists regarding personality changes following the transplantation of organs other than the heart. Furthermore, minimal quantitative evidence exists to determine the frequency of personality changes following the transplantation of any organ.

In this paper, we explore subjective reports of personality changes in individuals who underwent transplantation of any organ. We also compare personality changes reported by heart transplant recipients with changes reported by recipients of other transplanted organs to determine if changes in personality vary with the organ being transplanted.

2. Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of people who live in the United States and had previously undergone organ transplantation at any time in their life. We collected demographic information and asked whether participants had experienced any changes in their personality since receiving their new organ, and if so, what these changes were.

2.1. Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited by communicating with transplant centers and transplant support groups either via telephone, email, or on Facebook during 2022. Transplant centers were identified through online searches and national transplant organizations. Support groups were found through Google searches and transplant forums. Since many of the phone numbers were medical offices that could not directly disclose patient information, or were numbers that were no longer in service, the majority of participants were recruited by advertising on Facebook to public organ transplant support groups or by requesting to join private groups. A Facebook page was specifically designed for this project. We identified and communicated with approximately 20 Facebook support groups. Initial contact with participants was made by email and phone. Recruitment ended in December 2022.

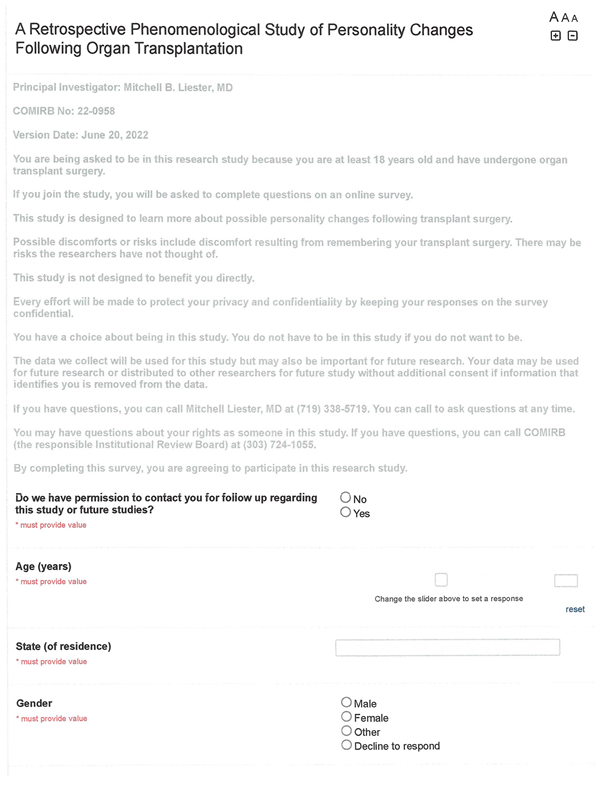

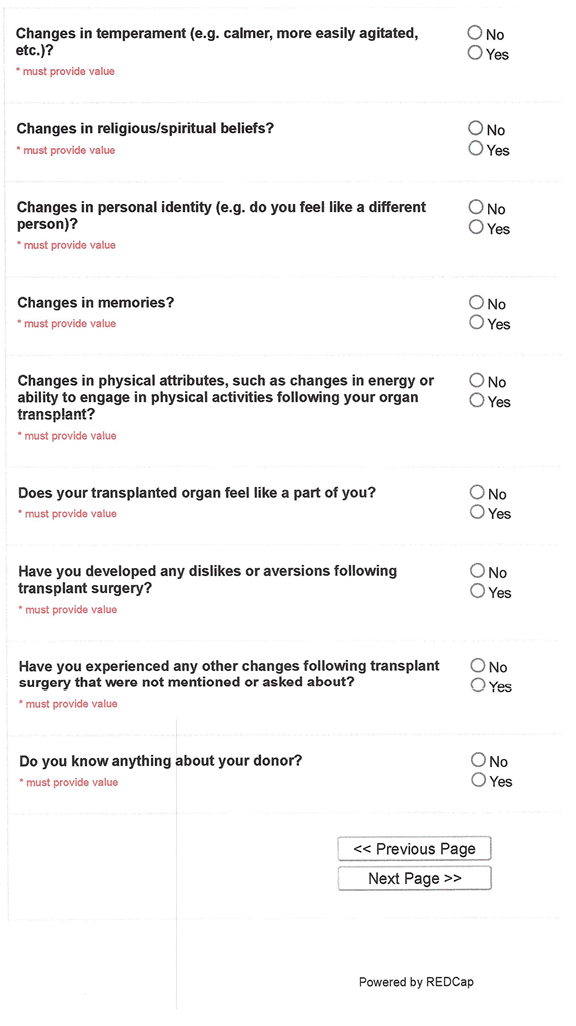

Participants were asked to complete an anonymous survey (see Appendix A) that was available online and took approximately 15 min to complete. A total of 67 participants initiated the survey. Participants who initiated but did not complete the survey were contacted by telephone, when a telephone number was provided, to inquire if they needed assistance completing the survey. A total of 47 participants completed the entire survey. All participants who completed the entire survey were included in our sample group. For this analysis, our sample included 23 heart transplant recipients and 24 recipients of other organs. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Colorado [21]. IRB approval was obtained from the University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, for this study (Submission ID APP001-2).

2.2. Survey

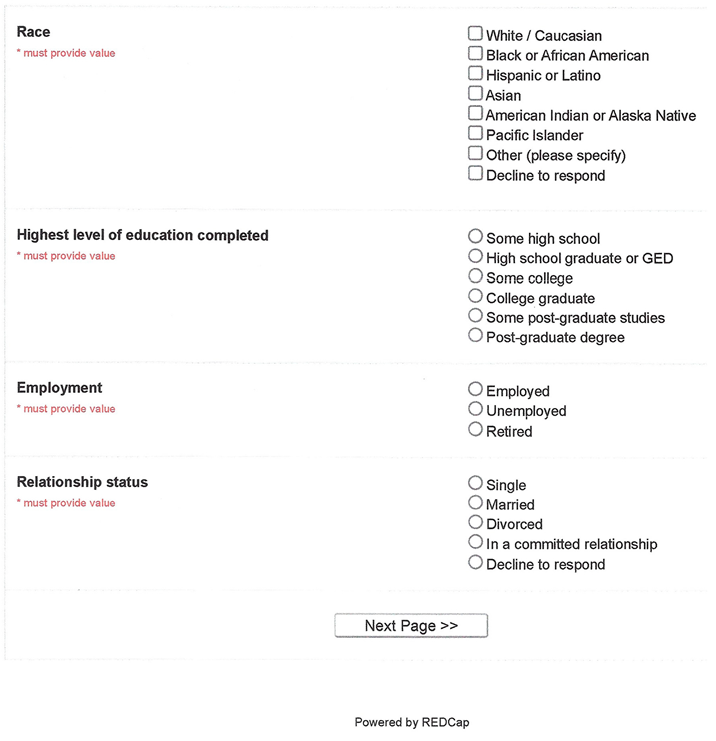

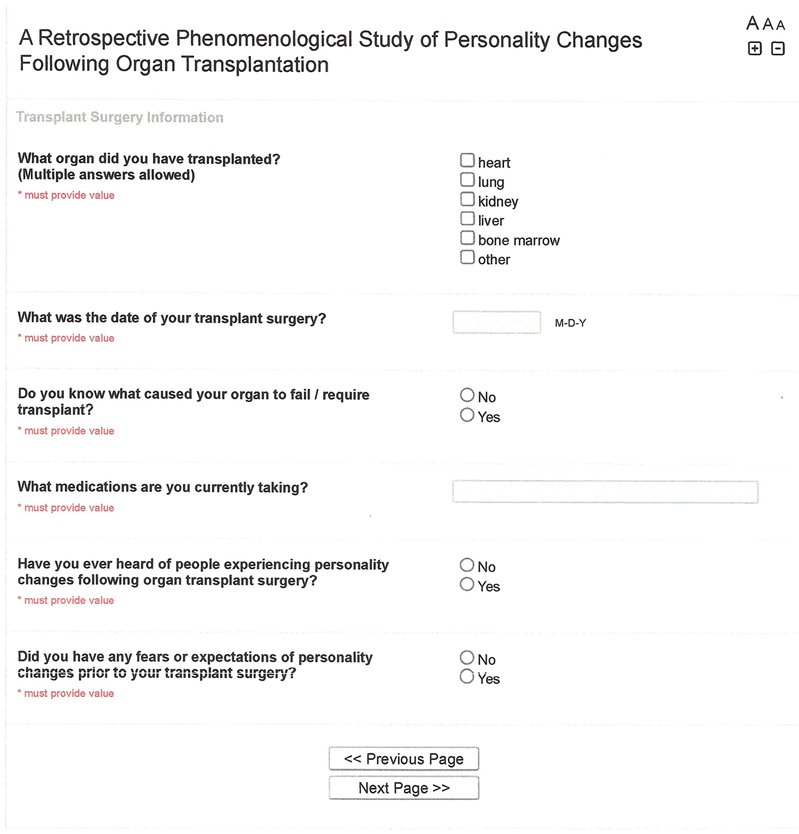

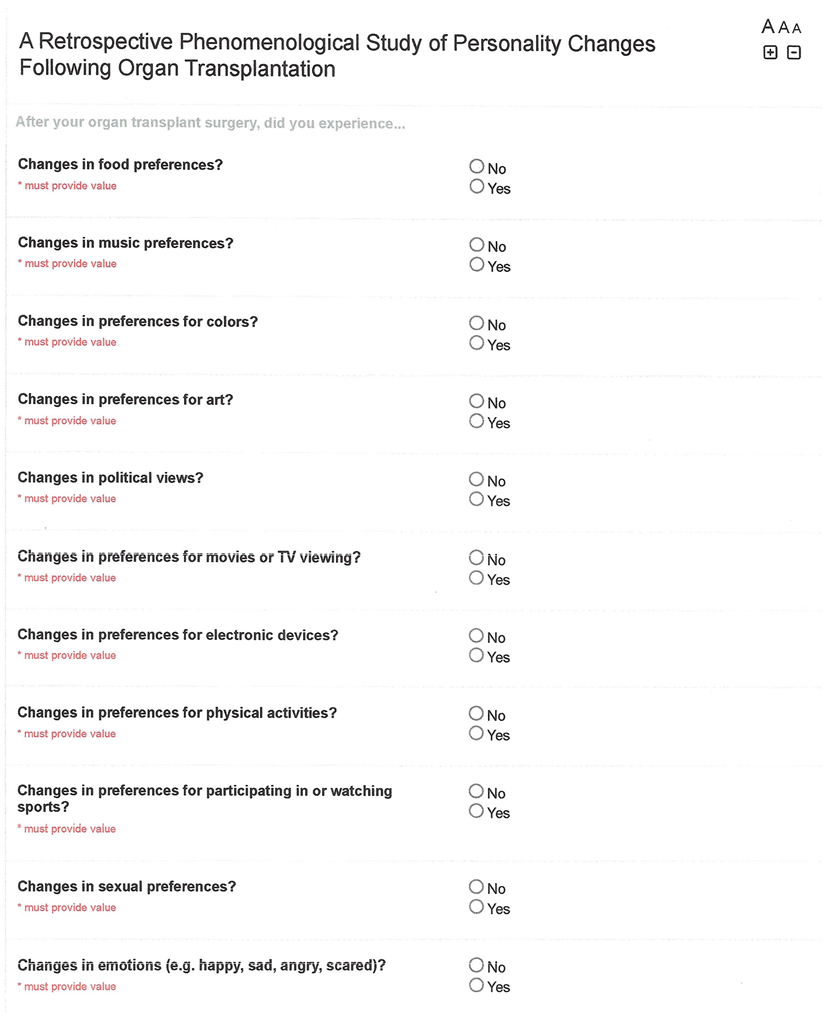

The survey (see Appendix A) was developed by our research team based on past personality assessments and characteristics previously reported to change following organ transplant. The questions went through multiple iterations and feedback from experts was incorporated. The final version of the survey consisted of 61 questions, which were divided into two sections. The first section included questions assessing demographics such as gender, age, and race. In addition, general questions were included to gather information about participants’ organ transplantation. The second section asked specific questions to assess self-reported types of personality changes that participants might have experienced either prior to, during, or after transplantation. Data were requested on 16 different types of personality changes, including changes in temperament, emotions, preferences for food, music, sports, colors, religion, etc. Participants were also asked to provide a free-text report of any other personality changes that were not specifically requested in the survey.

2.3. Analytical Methods

Analyses were chosen based on the variable type and distribution. Statistical comparisons were made between heart versus other recipients using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests with a 0.05 level of significance. p-values were obtained using chi-square tests comparing proportions between heart transplant versus other organ transplant recipients. When the counts were small, a Fisher’s exact test was used instead. An alpha value of 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance for all comparisons.

Data are reported for all participants collectively, as well as by the type of organ transplant (heart vs. other). These two groups were selected in order to help determine if personality changes were isolated to heart transplant recipients, as well as to compare and contrast reported changes between the heart and other organ transplant recipients. There were 3 participants who reported having more than one organ transplant. These included 1 participant who received a heart and a lung transplant and 2 participants who received a kidney and other (unspecified) organ transplant. These individuals were included in the analysis, with the heart/lung recipient being included in the heart group and the kidney/other recipients being included in the other group.

3. Results

A total of 67 participants initiated the survey and 47 completed the entire survey. For this analysis, our sample included 23 heart transplant recipients and 24 other organ transplant recipients. The demographic characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. Nearly half of the participants were heart transplant recipients. Other organs transplanted include the kidney, lung, and liver. Among all transplant recipients, the mean age was 61.9 years old, with over 80% being Caucasian and 60% being retired. The demographic data were similar when comparing heart transplants to other organ transplants. There was a non-significantly larger percentage of males who received a heart transplant (60.9%) compared to other organ transplants (42.7%) (p = 0.14). Approximately 38.3% of all transplant recipients had heard of personality changes occurring due to transplant, yet less than 8.5% were concerned with experiencing personality changes.

Table 1.

Demographics.

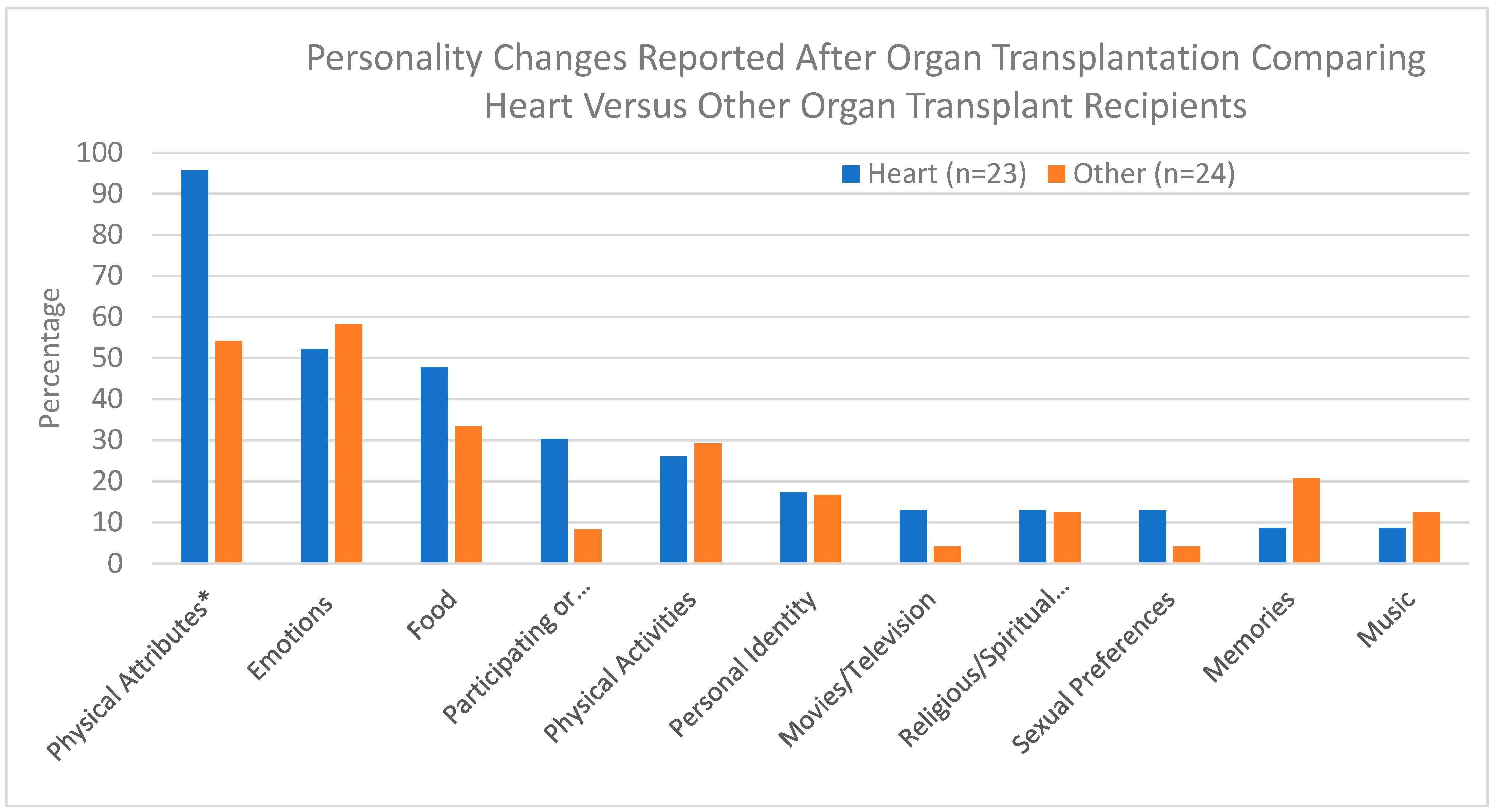

Personality changes reported following transplantation are listed in Table 2. Among heart transplant recipients, a change in physical attributes was the most common change reported, with 95.7% reporting a change in comparison to 54.2% among other organ transplants (p = 0.03). One possible explanation for this finding is that heart transplant recipients experienced improved cardiac output following their transplant resulting in increased energy and increased tolerance of physical activities.

Table 2.

Reported personality changes.

When excluding changes in physical attributes, 89.3% of all transplant recipients reported experiencing a personality change after receiving their organ transplant. Other changes that were more prevalent among heart transplant recipients, but not statistically significant, included participation in or watching sporting activities (30.4% vs. 8.9%), temperament (60.9% vs. 50%), and food preferences (47.8% vs. 33.3%). These changes could be related to a transfer of cellular memory from donors to recipients, although further studies are needed to confirm or disprove this hypothesis. Also, the small number of subjects in our study may explain why statistical significance was not achieved.

A change in memories was more commonly reported among other organ transplants compared to heart (20.8% vs. 8.7%). The explanation for this finding is unclear. It is possible that the small number of subjects in our study produced a statistical artifact. A future study involving a larger number of subjects would help to validate or contradict this finding. The most commonly reported change among other organ transplants was in emotions, although this was similar among heart transplants (58.3% vs. 52.2%). The finding that a similar number of heart and other organ transplant recipients reported changes in emotions following their surgeries suggests this change may occur as a result of the effects of the surgery rather than being a consequence of the transfer of cellular information related to the specific type of organ being transplanted. It is also plausible that changes in emotions occur as a result of any organ being transplanted due to the transfer of cellular memory between donor and recipient. Negligible differences in percentages were observed with other personality attributes when comparing heart and other organ transplants, and/or relatively few individuals reported experiencing these personality changes.

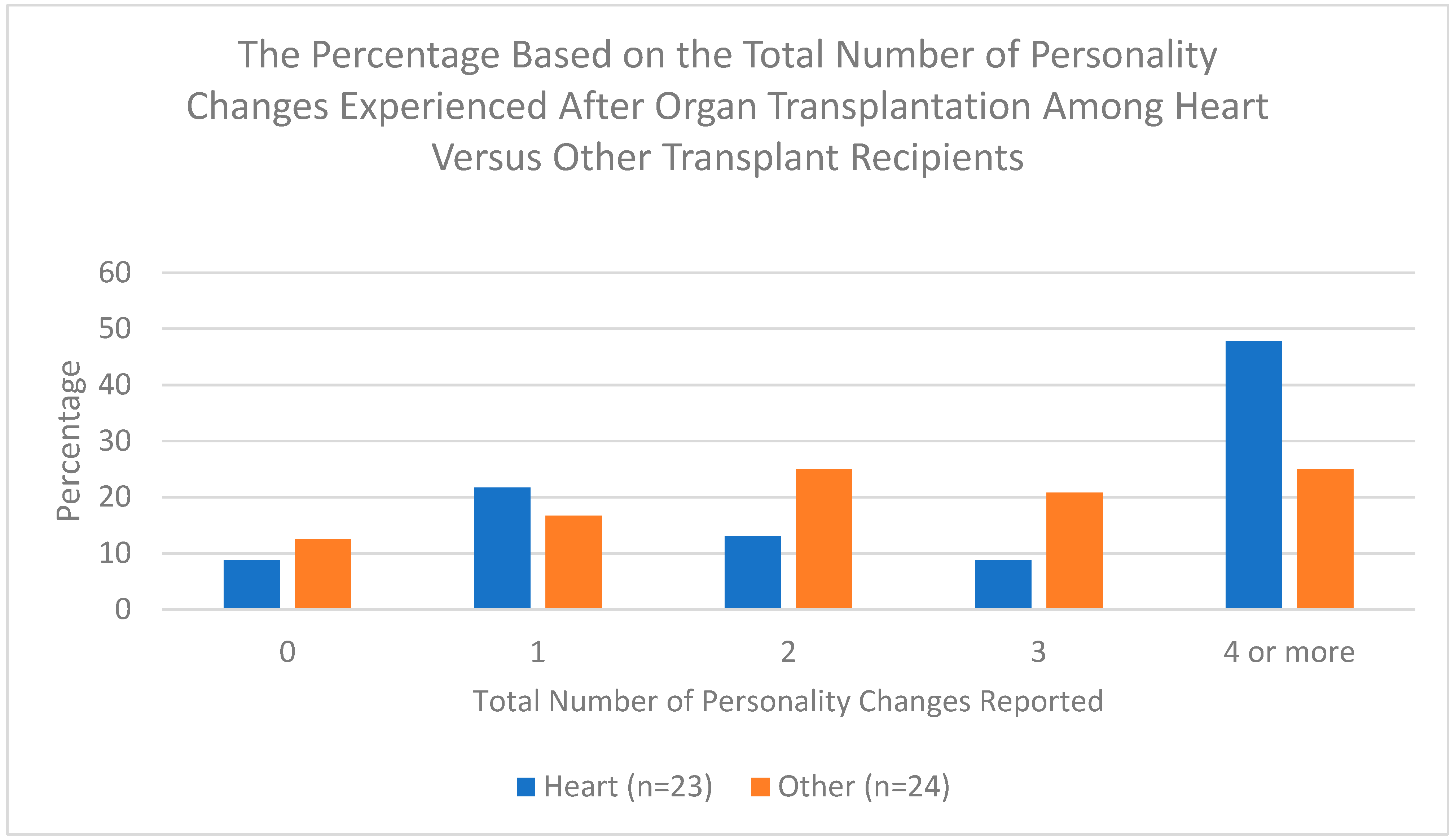

Table 3 summarizes the total number of personality changes presented in Table 2 that participants experienced after transplantation, excluding a change in physical attributes. Among all transplant recipients, 36.2% reported having four or more personality changes. When stratified by type of transplant, heart transplants were more likely to report having four or more personality changes compared to other organ transplants (47.8% vs. 25.0%), although this was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Summary of number of changes per group.

Figure 1 shows the types of personality changes reported after organ transplantation and compares such changes following heart versus other organ transplantation. The most pronounced changes reported were in physical attributes and these were more common following heart transplant than other organs. As previously noted, this finding may indicate cardiac effects, such as improved cardiac output and exercise tolerance.

Figure 1.

Personality changes reported after organ transplantation. * The most pronounced changes reported were in physical attributes.

The total number of personality changes experienced following organ transplantation is shown in Figure 2. Among heart transplant recipients who reported personality changes after receiving their new heart, nearly half described experiencing four or more types of personality changes whereas only one fourth of recipients who received other organs reported experiencing four or more personality changes. This finding suggests heart transplantation may have a broader range of influence on personality changes than the transplantation of other organs.

Figure 2.

Total number of personality changes reported.

4. Discussion

The majority of participants (89.3%) who underwent organ transplant reported changes in their personality following transplantation. This finding is much higher than was found in Bunzel et al.’s study and likely represents volunteer selection bias resulting from our recruitment of individuals to participate in a study that explicitly stated it was examining personality changes following organ transplants. Individuals who have not experienced personality changes might be less likely to participate in such a study. Despite potential selection bias, our finding corroborates previous studies demonstrating the occurrence of personality changes following transplant surgery. Such changes have the potential to influence transplant outcomes, as psychiatric issues have been shown to influence post-transplant morbidity and mortality [22].

The finding that some patients experience fears about the possibility of personality changes following organ transplant is an issue that should be addressed with potential transplant recipients prior to undergoing transplant surgery, as such a discussion might reduce transplant surgery hesitancy and potentially improve post-transplant treatment compliance.

The percentage of participants reporting any personality changes was comparable between heart transplant recipients (91.3%) and other organ transplant recipients (87.5%). These results suggest personality changes following any organ transplant are common, although this may again involve selection bias. The finding of a similar rate of personality changes following both heart and other organ transplants is a new finding. Previous studies have not compared personality changes in these two categories.

In looking at the types of personality changes reported by transplant recipients, the only statistically significant difference between heart and other organ recipients was a change in physical attributes. Although other differences were observed between these groups when looking at specific types of personality changes, the number of participants in each group was too small to achieve statistical significance. Overall, the similarities between the two groups suggest heart transplant recipients may not be unique in their experience of personality changes following transplantation, but instead such changes may occur following the transplantation of any organ.

This study was not designed to confirm reported personality changes with collateral contacts or evaluate the impact of such changes on the individuals who experienced the changes. Prospective studies are needed to determine if subjective reports of personality changes match reports from collateral contacts and to evaluate the impact of such changes on recipients’ post-transplant mental health and adjustment to their new organs. Our study was also not designed to determine the cause of personality changes following organ transplantation. Hypotheses regarding such mechanisms are numerous, as previously discussed, and it is possible that multiple mechanisms play a role. Also, these mechanisms may not be mutually exclusive (i.e., more than one mechanism may be involved) and mechanisms that have not yet been identified may contribute to these changes.

The limitations of our study include the small sample size (47 participants) which limits the generalizability of our findings. Our recruitment strategy, which primarily involved soliciting participants via Facebook and support groups, could introduce selection bias and may not accurately represent the broader transplant recipient population. Another limitation is potential selection bias. Recipients who experienced personality changes following organ transplantation might be more likely to respond to an online survey that was described as exploring such changes than recipients who experienced no personality changes. Also, our identification of personality changes following transplantation is based solely on self-reports. The reliance on self-reported data can lead to subjective bias. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of our study which precludes any objective assessment of pre-transplant personality. The absence of multiple, corroborating informants in the evaluation of personality changes is another limitation. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of our study restricts establishing causality.

Further studies are needed to determine the etiological factors contributing to personality changes following organ transplantation and to determine if such changes are more common with specific types of organs. Future studies could benefit from the use of reliable and valid psychiatric scales. Also, prospective studies utilizing pre-transplant and post-transplant assessments of personality could help to objectively ascertain personality changes. These objective findings could then be compared with subjective reports of personality changes to reduce participant bias. Also, interviews with family members and friends of donors could help to identify donors’ personality characteristics which could then be compared with newly acquired personality changes in recipients to determine if there are any matching characteristics. Another method that could be used to explore the transfer of personality traits via organ transplant would be to conduct a prospective study of transplant recipients who receive a donated organ from a living donor (e.g., a kidney or liver transplant). This would allow pre-transplant and post-transplant personality assessments to be carried out in both donors and recipients. These assessments could then be compared to determine if any donor personality traits have been transferred to the recipients. Studies examining potential personality changes in children and adults who undergo transplantation would be helpful in determining whether long-lasting personality characteristics are more or less likely to be transferred from donors to recipients than personality characteristics of shorter duration. Finally, a larger sample size would help to determine changes that are statistically significant versus changes that are an artifact resulting from a smaller study population.

In summary, our study confirms the findings of previous studies that found personality changes occur in some individuals following organ transplantation. Our study expands upon these previous studies by demonstrating recipients of organs other than the heart may experience personality changes similar to those experienced by heart transplant recipients.

Author Contributions

B.C.: study conceptualization and design; acquisition and interpretation of the data; writing—review and editing. L.K.: study conceptualization and design; data acquisition; writing—review and editing. M.S.: study conceptualization and design; data acquisition; writing—review and editing. L.H.: study conceptualization and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing—review and editing. B.W.: study conceptualization and design; writing—review and editing. M.L.: study conceptualization and design; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and determined to be exempt from the need for Institutional Review Board review by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) (protocol number 22-0958 and date of determination 27 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey

References

- Elflein, J. Estimated Number of Organ Transplantations Worldwide in 2021. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/398645/global-estimation-of-organ-transplantations/#:~:text=Global%20number%20of%20organ%20transplantations%202021&text=In%202021%2C%20there%20were%20a,can%20be%20challenging%20and%20complex (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Cleveland Clinic. Heart Transplant. 2023. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/17087-heart-transplant (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Anthony, S.J.; Nicholas, D.B.; Regehr, C.; West, L.J. The heart as a transplanted organ: Unspoken struggles of personal identity among adolescent recipients. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearsall, P.P. The heart’s code: Tapping the wisdom and power of our heart energy. In The New Findings about Cellular Memories and Their Role in the Mind/Body/Spirit Connection; Broadway: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sanner, M.A. Transplant recipients’ conceptions of three key phenomena in transplantation: The organ donation, the organ donor, and the organ transplant. Clin. Transplant. 2003, 17, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunzel, B.; Schmidl-Mohl, B.; Grundböck, A.; Wollenek, G. Does changing the heart mean changing personality? A retrospective inquiry on 47 heart transplant patients. Qual. Life Res. 1992, 1, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, P.A.; Kornfeld, D.S. Psychiatric outcome of heart transplantation. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1989, 11, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearsall, P.; Schwartz, G.E.; Russek, L.G. Changes in heart transplant recipients that parallel the personalities of their donors. J. Near-Death Stud. 2002, 20, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, C.; Novak, W. A Change of Heart: A Memoir; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, F.M. Psychiatric aspects of heart transplantation. Br. J. Psychiatry 1993, 163, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.A.; Starling, R.C.; Myerowitz, P.D.; Haas, G.J. Neuropsychological function in patients with end-stage heart failure before and after cardiac transplantation. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1995, 91, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, I.A. Psychiatric complications of cardiac transplantation. Semin. Psychiatry 1971, 3, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mauthner, O.E.; De Luca, E.; Poole, J.M.; Abbey, S.E.; Shildrick, M.; Gewarges, M.; Ross, H.J. Heart transplants: Identity disruption, bodily integrity and interconnectedness. Health 2015, 19, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, A.M., III; Watts, D.; Karp, R. Evaluation of cardiac transplant candidates: Preliminary observations. Psychosomatics 1984, 25, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.M.; Chang, V.P.; Esmore, D.; Spratt, P.; Shanahan, M.X.; Farnsworth, A.E.; Keogh, A.; Downs, K. Psychological adjustment after cardiac transplantation. Med. J. Aust. 1988, 149, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, W.F.; Myers, B.; Brennan, A.F.; Davis, M.H.; Lippmann, S.B.; Gray, L.A., Jr. Pool GE. Psychopathology in heart transplant candidates. J. Heart Transplant. 1988, 7, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lunde, D.T. Psychiatric complications of heart transplants. AORN J. 1969, 10, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabler, J.B.; Frierson, R.L. Sexual concerns after heart transplantation. J. Heart Transplant. 1990, 9, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lakota, J.; Jagla, F.; Pecháňová, O. Heart memory or can transplanted heart manipulate recipients brain control over mind body interactions? Act. Nerv. Super. Rediviva 2021, 63, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liester, M.B. Personality changes following heart transplantation: The role of cellular memory. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 135, 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfieri, L.; Gitto, S.; Vukotic, R.; Andreone, P.; Marra, F.; Morelli, M.C.; Cescon, M.; Grandi, S. Impact of psychosocial status on liver transplant process. Ann. Hepatol. 2019, 18, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).