Providers’ Perceptions of Respectful and Disrespectful Maternity Care at Massachusetts General Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

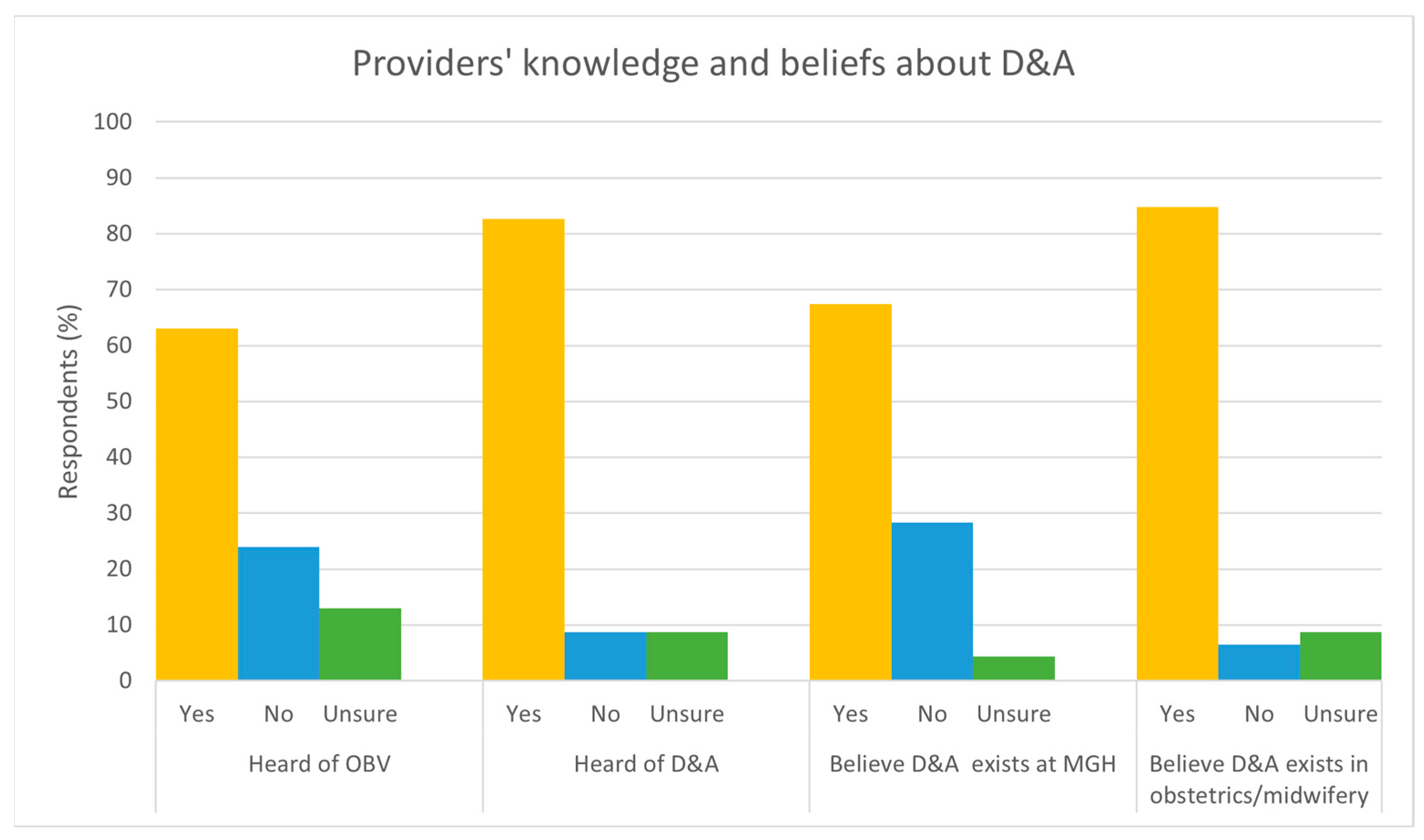

3.2. Knowledge of Disrespectful Care

3.3. Disrespectful Care Witnessed

“There are times when I feel the language people use, whether intentionally or not, can sound rude and disrespectful.”(Respondent 33)

“Conversations outside of the room about a patient or family member that is judgmental or unkind.”(Respondent 27)

“Adequate consenting by providers for medications and procedures in labor feels inadequate. Many of the information that I hear providers offer to patients during care planning feels incomplete and biased towards what the provider most wants the patient to do/feels most convenient.”(Respondent 16)

“Trying multiple times to place cook balloons on patients who are uncomfortable.”(Respondent 41)

“After traumatic cook balloon placement, MD agreed he wasn’t going to put balloon to tension right away and then pulled balloon so hard that patient had vagal response and prolonged deceleration that resulted in unnecessary intervention and unnecessary emotional and physical trauma to patient.”(Respondent 13)

“Often a lack of respect and consideration of patients whose primary language is not English—increasing volume, not addressing them directly, making side comments to staff.”(Respondent 42)

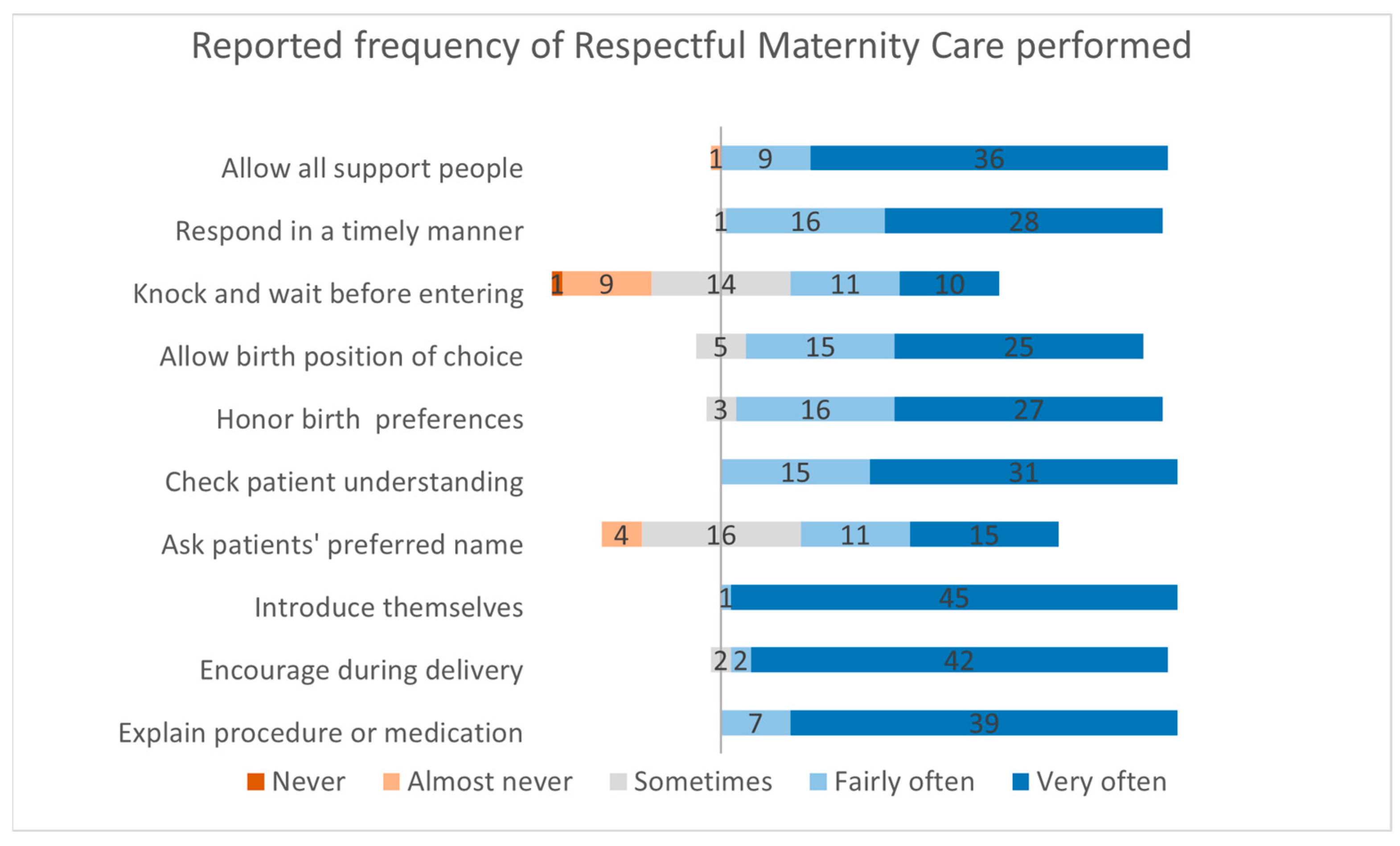

3.4. Respectful Care Performed

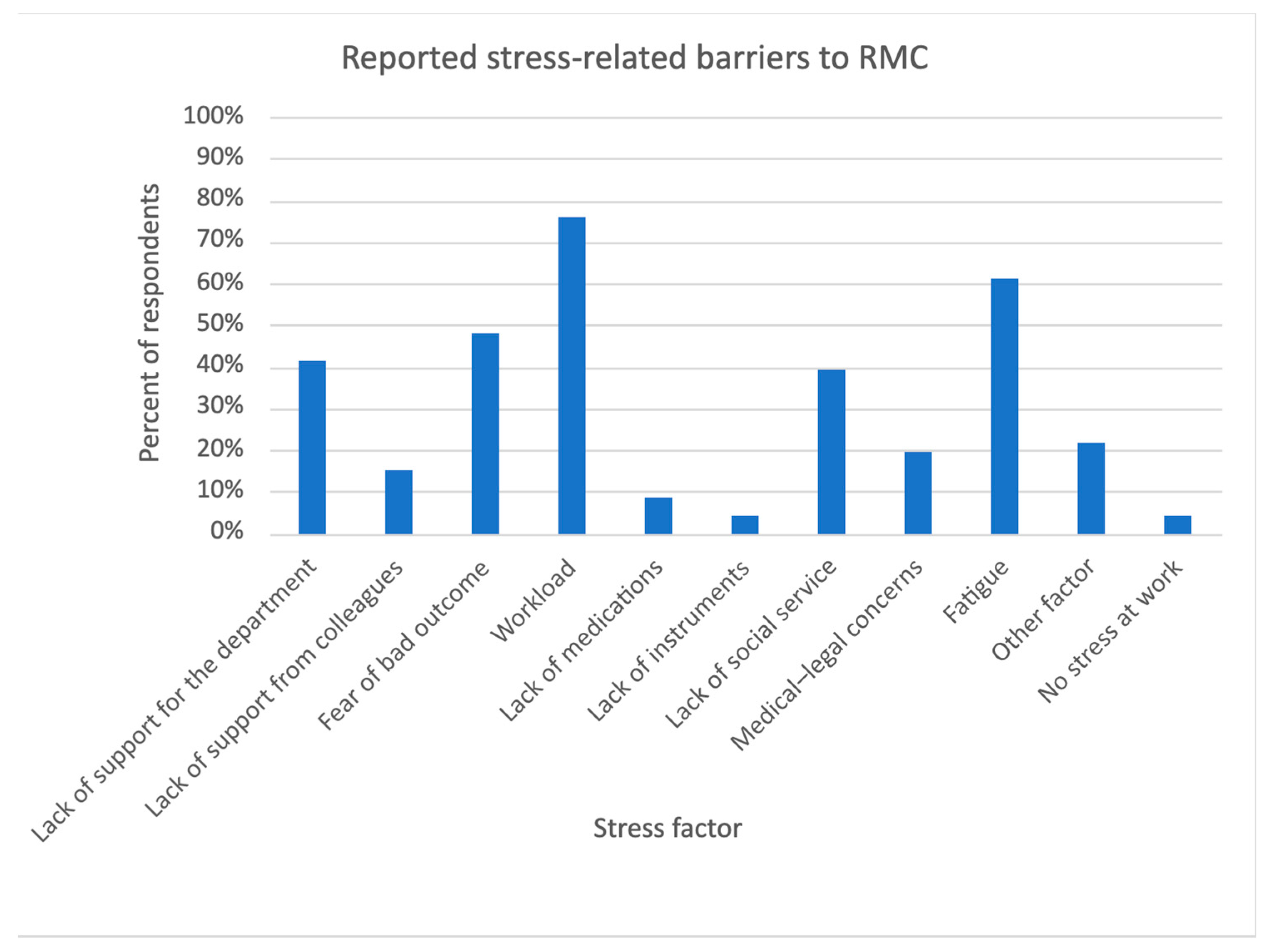

3.5. Stress and Support Factors

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse during Facility-Based Childbirth; WHO statement; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, D.; Hill, K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth: Report of a Landscape Analysis. USAID-TRAction Project; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, W.; Bayou, N.B.; Garedew, M.G. Magnitude of disrespectful and abusive care among women during facility-based childbirth in Shambu town, Horro Guduru Wollega zone, Ethiopia. Midwifery 2020, 83, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotte, V.; Chaudhary, A.; Goodman, A. “At Least Your Baby Is Healthy” Obstetric Violence or Disrespect and Abuse in Childbirth Occurrence Worldwide: A Literature Review. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 10, 1544–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, E.; Moti, G.; Gelan, G.; Creedy, D.K.; Gabriel, L.; Hastie, C. Impact of disrespectful maternity care on childbirth complications: A multicentre cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Vázquez, S.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M. Relationship between perceived obstetric violence and the risk of postpartum depression: An observational study. Midwifery 2022, 108, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escañuela Sánchez, T.; Linehan, L.; O’Donoghue, K.; Byrne, M.; Meaney, S. Facilitators and barriers to seeking and engaging with antenatal care in high-income countries: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e3810–e3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM): A Renewed Focus on Improving Maternal and Newborn Health and Wellbeing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tey, N.P.; Lai, S.L. Correlates of and Barriers to the Utilization of Health Services for Delivery in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 423403. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2013/423403 (accessed on 25 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Dyer, L.; Felker-Kantor, E.; Benno, J.; Vilda, D.; Harville, E.; Theall, K. Maternity Care Deserts and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality in Louisiana. Womens Health Issues Off. Publ. Jacobs Inst. Womens Health 2021, 31, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J. Womens Health 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A.; Zeitlin, J. Improving hospital quality to reduce disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliason, E.L. Adoption of Medicaid Expansion Is Associated with Lower Maternal Mortality. Womens Health Issues 2020, 30, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R. Family Leave and Maternal Mortality in the US. JAMA 2023, 330, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheyfets, A.; Dhaurali, S.; Feyock, P.; Khan, F.; Lockley, A.; Miller, B.; Cohen, L.; Anwar, E.; Amutah-Onukagha, N. The impact of hostile abortion legislation on the United States maternal mortality crisis: A call for increased abortion education. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1291668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, P.; Singh, K.; Shekhar, S.; Agrawal, N.; Misra, S. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health due to delay in seeking health care: Experience from a tertiary center. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 152, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.L.; Hoyert, D.L.; Goodman, D.A.; Hirai, A.H.; Callaghan, W.M. Contribution of maternal age and pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality ratios in the United States, 1978–2012. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 352.e1–352.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyert, D. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, S.; Beauregard, J.; Nije, F. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/data-research/mmrc-2017-2019.html (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Hollier, L.M.; Busacker, A.; Njie, F.; Syverson, C.; Goodman, D.A. Pregnancy-Related Deaths Due to Hemorrhage: Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, 2012–2019. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 144, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, K.L.; Davis-Floyd, R.; Stewart, K.; Cheyney, M. Obstetric iatrogenesis in the United States: The spectrum of unintentional harm, disrespect, violence, and abuse. Anthropol. Med. 2021, 28, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.H.; Henley, M.M.; Seacrist, M.; Roth, L.M. Bearing witness: United States and Canadian maternity support workers’ observations of disrespectful care in childbirth. Birth Berkeley Calif. 2018, 45, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Underhill, K.; Aubey, J.J.; Samari, G.; Allen, H.L.; Daw, J.R. Disparities in Mistreatment During Childbirth. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e244873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Altman, M.R.; Castillo, E.; Bernal, N.; Jones, L.; Camara, T.; Carrasco, Z.; Williams, S.; Sudhinaraset, M.; Kuppermann, M. Adaptation of the Person-Centered Maternity Care Scale in the United States: Prioritizing the Experiences of Black Women and Birthing People. Womens Health Issues 2022, 32, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, G.; Minckas, N.; Tan, D.; Haghparast-Bidgoli, H.; Batura, N.; Mannell, J. Feminisation of the health workforce and wage conditions of health professions: An exploratory analysis. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.J.; Truong, S.; DeAndrade, S.; Jacober, J.; Medina, M.; Diouf, K.; Meadows, A.; Nour, N.; Schantz-Dunn, J. Respectful Maternity Care in the United States-Characterizing Inequities Experienced by Birthing People. Matern. Child Health J. 2024, 28, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.L.; Perez, S.L.; Walker, A.; Estriplet, T.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Auguste, T.C.; Crear-Perry, J.A. The Cycle to Respectful Care: A Qualitative Approach to the Creation of an Actionable Framework to Address Maternal Outcome Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, A.G.; Jungbauer, R.M.; Skelly, A.C.; Hart, E.L.; Jorda, K.; Davis-O’Reilly, C.; Caughey, A.B.; Tilden, E.L. Respectful Maternity Care: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Kelly, A.M.; Buback, L.; Asunka, J.; Kirumbi, L.; Lyndon, A. Providers’ perceptions of disrespect and abuse during childbirth: A mixed-methods study in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud, Y.A. Vital Signs: Maternity Care Experiences—United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Ecuyer, K.M.; Subramaniam, D.S.; Swope, C.; Lach, H.W. An Integrative Review of Response Rates in Nursing Research Utilizing Online Surveys. Nurs. Res. 2023, 72, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervenak, F.A.; McLeod-Sordjan, R.; Pollet, S.L.; De Four Jones, M.; Gordon, M.R.; Combs, A.; Bornstein, E.; Lewis, D.; Katz, A.; Warman, A.; et al. Obstetric violence is a misnomer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S1138–S1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, C.; Wint, K.; Burke, J.; Chang, J.C.; Documet, P.; Kaselitz, E.; Mendez, D. Overlap between birth trauma and mistreatment: A qualitative analysis exploring American clinician perspectives on patient birth experiences. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N.; Brown, G.D.; Hicks, L.L. From a blame culture to a just culture in health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Occupation at MGH | |

| Nurse | 23 (50.0%) |

| Midwife | 8 (17.4%) |

| Physician | 15 (32.6%) |

| Age | |

| Less than 30 years old | 10 (21.7%) |

| 30–39 years old | 17 (37%) |

| 40–49 years old | 8 (17.4%) |

| 50 or older | 11 (23.9%) |

| Gender | |

| Man | 4 (8.7%) |

| Woman | 42 (91.3%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Education | |

| Associate’s degree or diploma program (e.g., ADN) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Bachelor’s degree (e.g., BSN) | 19 (41.3%) |

| Master’s degree (e.g., MSN, CNM) | 11 (23.9%) |

| Doctorate degree (e.g., MD, DNP) | 15 (32.6%) |

| Race | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3 (6.5%) |

| Black or African American | 3 (6.5%) |

| White | 37 (80.4%) |

| Multiracial/Other race | 2 (4.3%) |

| NA | 1 (2.2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (6.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic or non-Latino | 42 (91.3%) |

| NA | 1 (2.2%) |

| Years of experience at MGH | |

| 1–4 years | 27 (58.7%) |

| 5–9 years | 5 (10.9%) |

| 10–14 years | 1 (2.2%) |

| 15+ years | 13 (28.3%) |

| Years of experience in obstetric care | |

| 1–4 years | 18 (39.1%) |

| 5–9 years | 9 (19.6%) |

| 10–14 years | 3 (6.5%) |

| 15+ years | 16 (34.8%) |

| Domain of Disrespect | Item | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal disrespect | Dismissing/disbelieving a patient’s reports of pain | 40 (87.0%) |

| Scolding | 29 (63.0%) | |

| Threatening with unnecessary C-section | 19 (41.3%) | |

| Other verbal/psychological disrespect | 19 (41.3%) | |

| Derogatory comment | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Physical disrespect | Vigorous/uncomfortable vaginal examinations | 30 (65.2%) |

| Not allowing patients’ position of choice in birth | 29 (63.0%) | |

| Other physical disrespect | 9 (19.6%) | |

| Restraining | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Privacy violations/Neglect/Unnecessary procedures | Asking private questions in the presence of others | 27 (58.7%) |

| Leaving patients unattended for long periods of time | 25 (54.3%) | |

| Neglecting a patient | 24 (52.2%) | |

| Medically unnecessary C-section | 15 (32.6%) | |

| Medically unnecessary episiotomy | 13 (28.3%) | |

| Delivery or examination in public | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Other disrespectful/abusive actions | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Discriminatory care | Discriminatory care based on physical characteristics | 31 (67.4%) |

| Discriminatory care based on race | 30 (65.2%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on culture | 28 (60.9%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on language | 21 (45.7%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on age | 20 (43.5%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on immigration status | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on the number of children | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on socioeconomic status | 13 (28.3%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on gender identity or sexual orientation | 12 (26.1%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on marital status | 6 (13%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on insurance status | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Discriminatory care based on other patient characteristics | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Performance of procedures without explanation | Artificial rupture of membrane | 18 (39.1%) |

| Episiotomy | 16 (34.8%) | |

| Stripping membrane | 16 (34.8%) | |

| Rectal exam | 11 (23.9%) | |

| Vaginal exam | 11 (23.9%) | |

| Placement of FSE or IUPC | 10 (21.7%) | |

| Placement of Foley catheter | 7 (15.2%) | |

| C-section | 6 (13%) | |

| Shaving | 6 (13%) | |

| Stitching | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Placement of the straight catheter | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Injection | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Use of assistive device for delivery | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Blood transfusion | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Sterilization | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Other procedure | 1 (2.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fachon, K.D.; Truong, S.; Narayan, S.; Buniak, C.D.; Vergara Kruczynski, K.; Cohen, A.; Barbosa, P.; Flynn, A.; Goodman, A. Providers’ Perceptions of Respectful and Disrespectful Maternity Care at Massachusetts General Hospital. Reprod. Med. 2024, 5, 231-242. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed5040020

Fachon KD, Truong S, Narayan S, Buniak CD, Vergara Kruczynski K, Cohen A, Barbosa P, Flynn A, Goodman A. Providers’ Perceptions of Respectful and Disrespectful Maternity Care at Massachusetts General Hospital. Reproductive Medicine. 2024; 5(4):231-242. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed5040020

Chicago/Turabian StyleFachon, Katherine Doughty, Samantha Truong, Sahana Narayan, Christina Duzyj Buniak, Katherine Vergara Kruczynski, Autumn Cohen, Patricia Barbosa, Amanda Flynn, and Annekathryn Goodman. 2024. "Providers’ Perceptions of Respectful and Disrespectful Maternity Care at Massachusetts General Hospital" Reproductive Medicine 5, no. 4: 231-242. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed5040020

APA StyleFachon, K. D., Truong, S., Narayan, S., Buniak, C. D., Vergara Kruczynski, K., Cohen, A., Barbosa, P., Flynn, A., & Goodman, A. (2024). Providers’ Perceptions of Respectful and Disrespectful Maternity Care at Massachusetts General Hospital. Reproductive Medicine, 5(4), 231-242. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed5040020