1. Introduction

Coronary angiography with PCI in patients with stable ischaemic heart disease (IHD) has robust data supporting improvements in symptoms and quality of life. As a consequence, PCI remains one of the most frequently performed invasive cardiac procedures [

1,

2]. Its utility is likely to further increase on the back of recent evidence demonstrating significant reductions in cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction in patients who present with ST elevated myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) who undergo staged PCI for complete coronary revascularisation [

3]. The benefits were consistently observed in patients who had elective PCI following their index acute coronary syndrome [

3].

Despite widespread use, there remains significant variability amongst PCI-performing centres surrounding the duration of monitoring for complications that may not be apparent during the initial procedure [

4]. In the absence of definitive studies examining specific durations of monitoring post elective PCI, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) recommended in 2009 that overnight stay was the standard of care following uncomplicated elective PCI [

4]. Over the years, the increasing use of trans-radial artery PCI coupled with technological advances in stent design and improvements in anti-platelet therapy have significantly reduced the risk of complications post PCI [

4,

5]. Radial arterial access has consistently been shown to be safe for performing PCI and is associated with reduced patient discomfort, bleeding complications and hospital length of stay (LOS) compared with femoral access [

6,

7,

8]. Same-day discharge (SDD) following PCI reflects a process where patients have their procedure, are monitored for a specified period of time and then discharged home on the same day if deemed safe.

In 2018, Amin et al. examined 672,470 patients undergoing elective PCI in US hospitals and reported that there was no higher risk of death, bleeding or acute myocardial infarction at 30, 90 or 365 days in patients who were managed with SDD [

9]. More recently, a large population-based cohort study of elective PCI patients from Canada in 2019 illustrated that patients who underwent SDD had no significant difference in the incidence of death or hospitalisation for acute coronary syndrome compared with non-SDD patients at 30 days [

10]. Such evolution in PCI has led to the thought that overnight observation may not be necessary for all elective PCI patients. SDD is not practised globally, and, indeed, most sites in Australia would routinely admit patients overnight for observation.

Finally, there is little debate that SDD is associated with objective reductions in hospital LOS and better use of healthcare resources. With the increasing pressure on hospitals to free hospital beds, especially during pandemic times, elective PCI without a requirement for overnight hospital admission remains an attractive prospect, given most hospitals operate at near maximum bed capacity [

11]. Moreover, admission to hospital can sometimes subject patients who are otherwise well to adverse events and potential for infection. SDD was associated with 50% lower hospital cost per patient undergoing PCI, with a mean saving of CAD 1086.8 per patient [

12]. SDD, therefore, effectively improves the value of PCI as it definitively reduces healthcare costs while concurrently allowing for greater patient satisfaction as patients are able to recover from the procedure in the familiarity of their homes [

5,

13].

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

This observational cohort study was performed in the Cardiology Catheter Lab, St George Hospital, Sydney, Australia. Elective PCI was defined as any coronary revascularisation procedure encompassing drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation or drug-eluting balloon (DEB) in a patient with stable ischaemic heart disease undergoing ad hoc or staged intervention. Consecutive patients who presented for elective PCI from 1 January 2017 through to 31 December 2019 were prospectively recruited as part of a registry. Their clinical, socio-demographic and procedural data were subsequently recorded into a database. PCI data were collected using McKesson software V7.0™. The South Eastern Sydney Local Health District human research ethics committee provided approval for PCI follow-up as quality assurance.

3.2. Procedure

All patients had dual anti-platelet therapy on board prior to PCI. Patients that were not normally on any anti-platelet agent received loading doses of 300 mg aspirin and 600 mg clopidogrel. All patients received pre-procedural sedation with midazolam and/or fentanyl at the discretion of the operator. Radial arterial access was used preferentially; otherwise, femoral access was gained. The access site was anaesthetised with lignocaine prior to insertion of a 6Fr radial sheath. All patients who had radial PCI received glyceryl trinitrate upon insertion of the radial sheath. The sheath was removed immediately after the procedure, and the point of puncture was compressed with a TR band (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). The band was deflated as per institutional policy.

3.3. Outcomes and Clinical Follow-Up

Our primary outcomes included 7-day major adverse cardiovascular endpoints (MACEs) and readmission to hospital within 30 days. Follow-up of all elective PCI patients was performed by cath lab staff by reviewing the electronic medical record as well as contacting the patients by telephone. Patients or their next of kin were asked about complications following PCI, including vascular access complications that may have required presentation to hospital or review by their local general practitioner. Information was also obtained regarding compliance with dual anti-platelet therapy. Data relating to mortality were obtained from electronic hospital records and next of kin.

3.4. Cost Determination

Information about cost differences between SDD and overnight admission was obtained following a discussion with the Finance department at our hospital. National weighted activity unit (NWAU) calculators were used to obtain specific cost estimates for overnight admission to hospital following a coronary angiogram, drug-eluting stent insertion, post-procedure pathology costs and the cost for an overnight stay in a monitored bed in the coronary care unit. Readmissions to hospital were not included in the cost analysis.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the following software programs: Microsoft Excel 2013™ and IBM SPSS 22™.

5. Discussion

Our single centre population-based study of patients undergoing elective PCI with SDD offers a new paradigm for PCI practice in Australia. Our results demonstrate that SDD is a safe and cost-effective way of managing patients who present for elective PCI.

Table 1 highlights the baseline characteristics of our patient population, which is in keeping with established demographic data on SDD post elective PCI. The mean age of our cohort was 67.6 years, which is higher than a previous French trial in this area, where there was a mean age of 62 years [

14]. Our patient population also had standard rates of prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including current and past smoking (44.9%) and type II diabetes mellitus (34.1%). Importantly, almost 98% of our patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography and then proceeded to ad hoc PCI, with a small proportion presenting for staged procedures.

More than 80% of our PCI patients were discharged home on the same day after the mandatory period of observation of 4–6 h. Our rates are considerably higher when compared with large randomised trial data comparing SDD with overnight admission post PCI [

5,

15]. The majority of PCI at our institution was performed on the LAD artery, followed by the RCA and then LCx, which is comparable to the established literature for outpatient PCI [

5]. The 2009 SCAI consensus guidelines had stipulated that anatomic lesions such as multi-vessel disease or bifurcation lesions are at higher risk for complications and, as such, may be better managed with overnight observation. However, our data highlights that these lesions can be just as effectively managed with SDD, a notion that is now reflected in the updated 2018 SCAI expert consensus document, which adjusted its recommendation due to the absence of evidence supporting overnight observation reducing risk to patients post PCI [

4].

The timeframe of 4–6 h of post procedural monitoring performed in our centre was chosen to avoid compromise to patient safety. The STRIDE study demonstrated that most of the complications post PCI occurred within 6 h and that none occurred between 6 and 24 h after PCI [

8]. Subsequent studies reinforced that the incidence of complications following elective PCI was low and that most complications usually occur within the first 6 h after PCI or after 24 h [

8]. Our data reinforce the notion that 4–6 h of monitoring post procedure could be considered the standard period of monitoring in patients who undergo SDD following PCI to ensure patient safety.

Our MACE data reflects a strong safety profile and low rates of procedural complications. The results from our study are slightly higher than those by Saad et al., who did not have any MACEs in their cohort of 300 patients who underwent SDD [

2]. Data from the US National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI database highlighted that the incidence of PCI-related complications was approximately 5% and that overall in-hospital mortality post PCI was 1% [

16]. Most significantly, our cohort of patients who were managed with SDD tended to have less re-hospitalisation than those who were admitted to hospital overnight following elective PCI. The observation that SDD patients had no difference in clinical outcomes at 30 days and had lower rates of clinical outcomes was reassuring and suggests that our patients were appropriately selected for discharge. Those patients who were admitted to hospital for further observation were admitted mainly for complications from access sites as well as for post-IVF hydration, which is in line with the 2018 SCAI expert consensus document recommendation about variables that are unfavourable for SDD [

4].

Importantly, our study also sought to examine the fiscal differences between SDD and overnight admission and place this in a contemporary Australian context, where there are ever-growing pressures on health budgets. As such, attempts at reducing LOS cost and improving hospital bed flow are very welcome from a health economic point of view. Amin et al. were able to show that simply switching from elective femoral PCI with an overnight stay to radial PCI with SDD, if done in 30% of elective PCI patients, would save up to USD 1 million in cost in PCI centres annually [

9]. North American data would suggest that SDD is able to save CAD 1141 or USD 5128 per PCI procedure [

9,

10]. Our data showed a cost saving of AUD 4817 per case with SDD, which amounts to a total saving of at least AUD 2,948,004 over three years for our local health district.

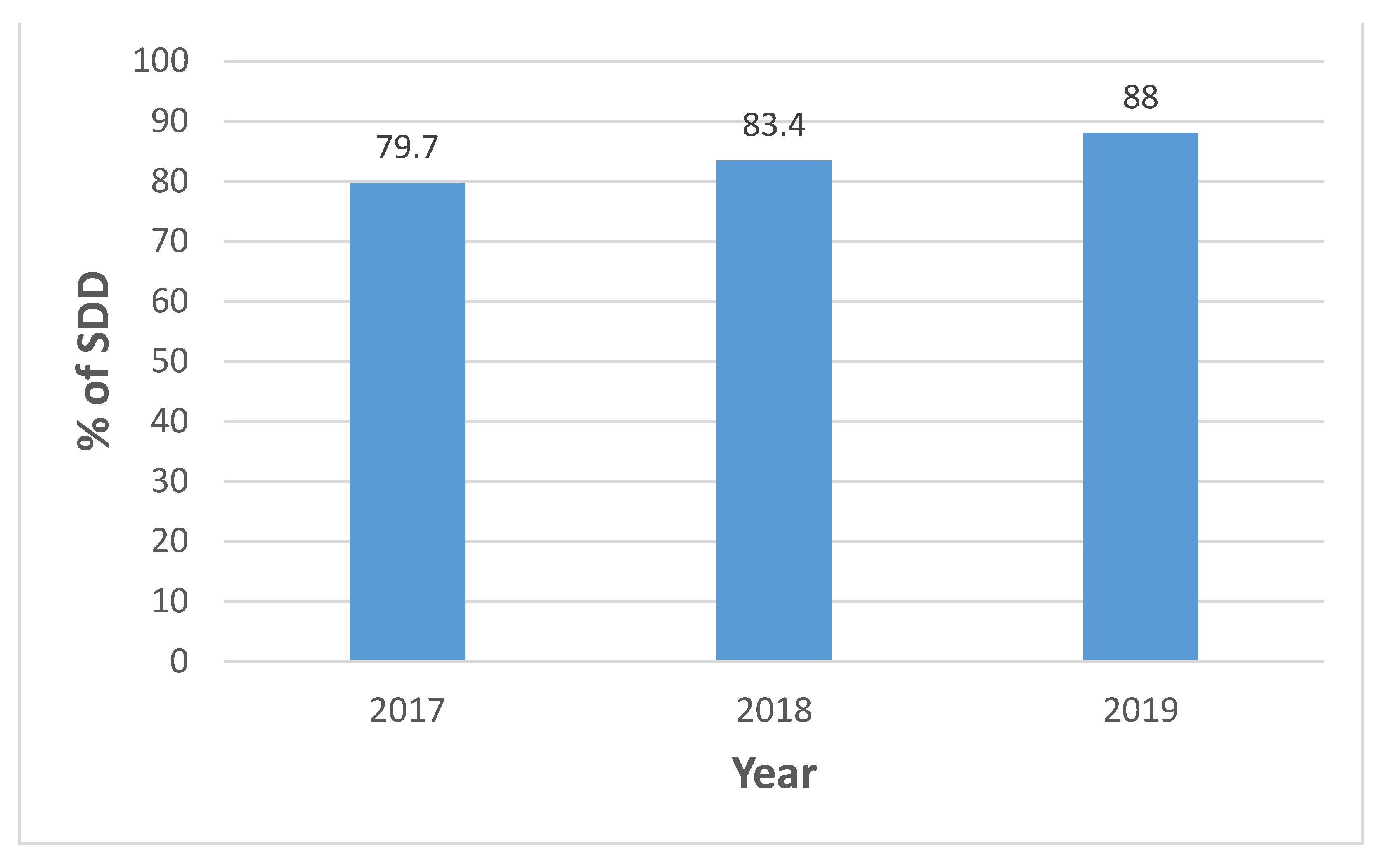

Further,

Figure 1 highlights that since 2017, our utilisation of SDD has increased precipitously, which is unique to our centre. Din et al. acknowledged that the rates of uptake of SDD vary around the world, with 57% of cardiologists in the United Kingdom and only 32% in Canada routinely practising it in the elective setting [

17]. Interestingly, our experience of SDD has coincided with more radial PCI being performed (79.0%), which is a trend observed internationally and that has been previously described in the literature. Radial PCI is associated with costs savings in excess of USD 800 per patient compared with femoral PCI [

18]. Our approach of SDD had the additional benefit of removing the chance of cancellations to staged PCI procedures due to overnight bed unavailability. Indeed, SDD post elective PCI was recently recommended as a strategy to improve cardiovascular healthcare services in the 2020 Cardiovascular Disease and COVID-19: Australian/New Zealand Consensus Statement [

19]. Our data add further weight to this recommendation and should assist in making clinicians aware of the safety of SDD and encouraging its more widespread use during non-pandemic times.

6. Limitations

Limitations of our study included that it was a retrospective cohort study and not a randomised clinical trial strictly comparing SDD to overnight admission at our institution and, as such, is prone to confounding and selection bias. However, our research aims were to examine the rates of SDD at St George Hospital and review its safety by examining clinical outcomes, which is illustrated by our data. Additionally, our 7-day follow-up for MACEs may not have been long enough. However, this interval was justified by the fact that most complications from elective PCI occur within the first 48 h. It may also have been helpful to examine re-hospitalisation as an outcome at longer intervals, such as 60 and 90 days. The mixture of radial and femoral procedures may also confound some of the results obtained. There were also patients who were lost to follow-up, but our clinical outcomes still demonstrate a robust safety profile from our single-centre cohort. Finally, it would be important to see if SDD can be safely applied in other aspects of interventional cardiology, namely, structural and electrophysiological procedures.