Unmasking the Fungal Menace: A Case Report of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of Maxilla

Abstract

1. Introduction

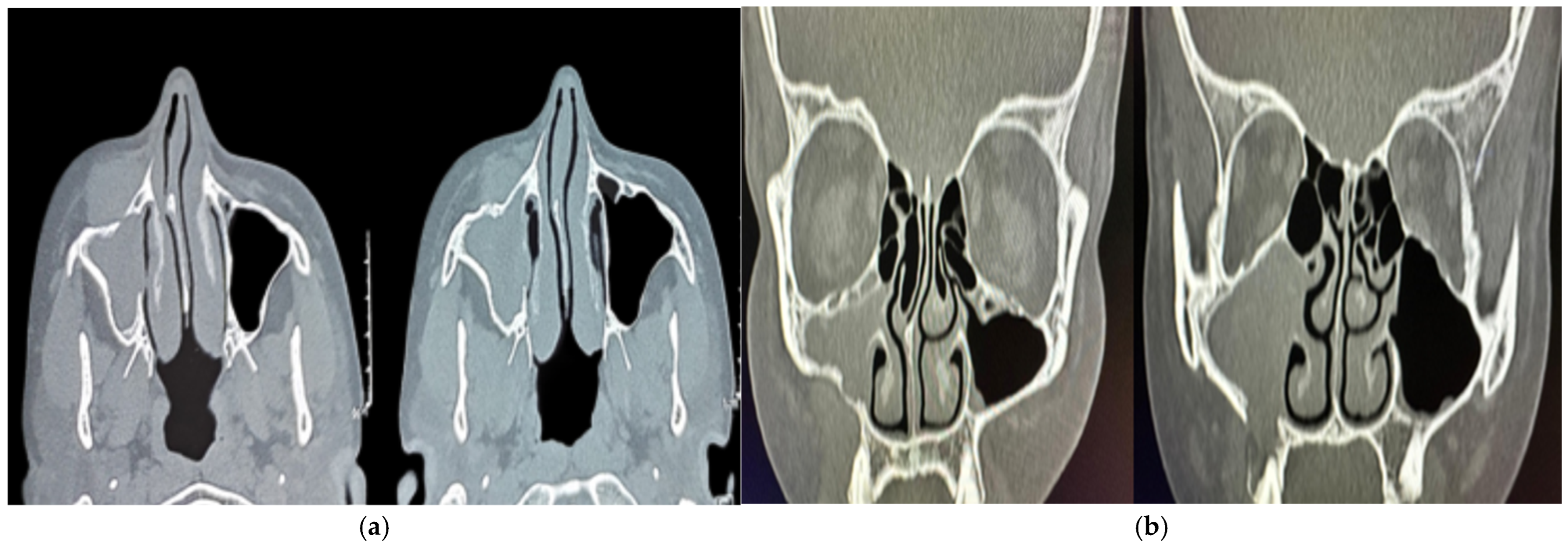

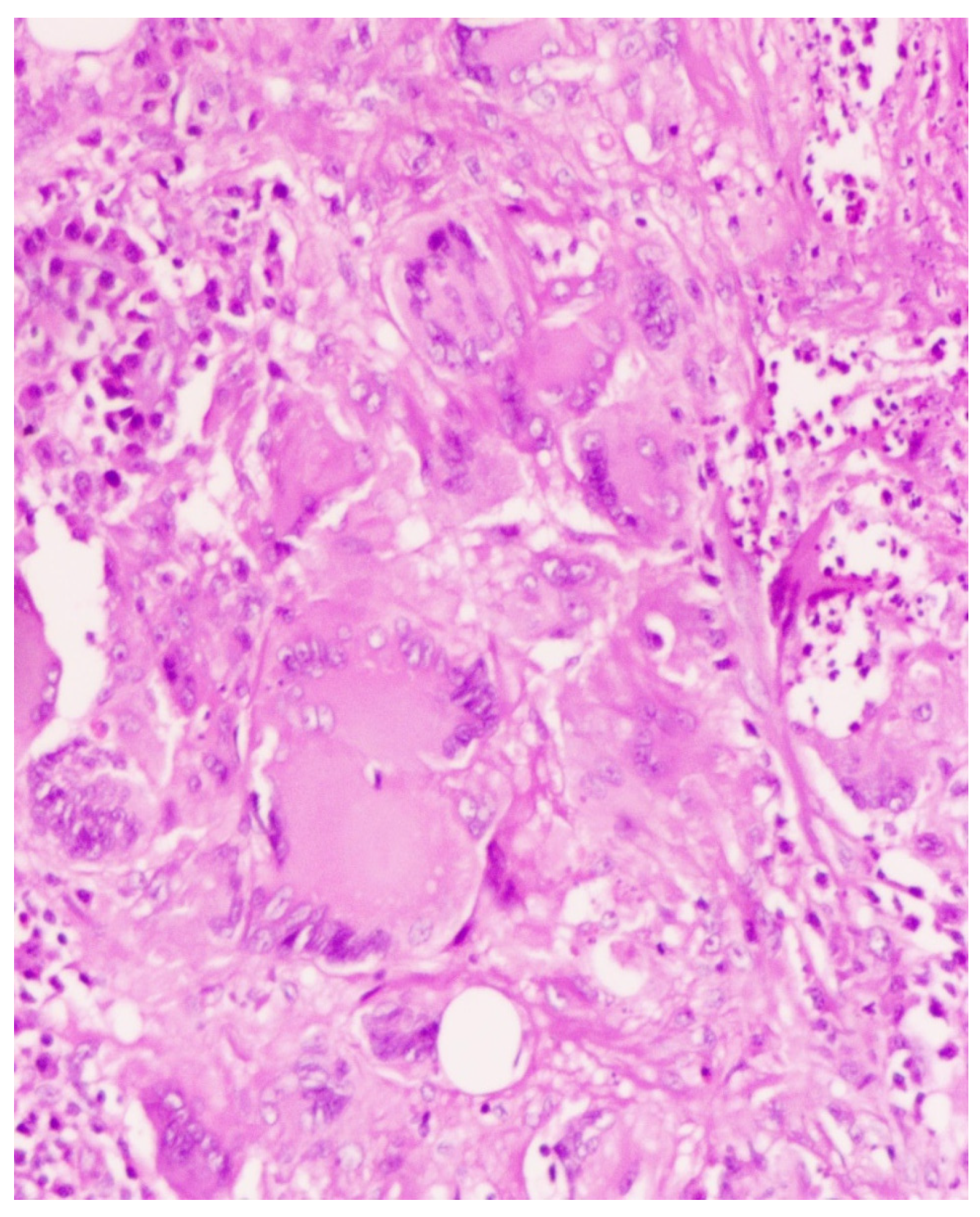

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jariwal, R.; Heidari, A.; Sandhu, A.; Patel, J.; Shoaepour, K.; Natarajan, P.; Cobos, E. Granulomatous Invasive Aspergillus flavus Infection Involving the Nasal Sinuses and Brain. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2018, 6, 2324709618770473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahethi, R.; Talmor, G.; Choudhry, H.; Lemdani, M.; Singh, P.; Patel, R.; Hsueh, W. Chronic invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis and Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: A systemic review of symptomatology and Outcomes. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaji-Kanayama, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Yasuda, M.; Sakiyama, E.; Shimura, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Kuroda, J. Chronic Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis with Atypical Clinical Presentation in an Immunocompromised Patient. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3225–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jang, H.U.; Jung, Y.Y.; Kim, J.S. Granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis extending into the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital floor: A case report. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2012, 1, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulut, H.T.; Kaplan, E.; Çoraplı, M. Acute and chronic invasive fungal sinusitis and imaging features: A review. J. Surg. Med. 2021, 5, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Yoon, T.M.; Lee, J.K.; Joo, Y.E.; Park, K.H.; Lim, S.C. Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of the Sphenoid Sinus. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 7, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisac, R.R.; Garber, M.; Mirza, A.; Shah, C.C. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis presenting with intracranial spread along large sphenoidal emissary foramen. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2021, 32, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, B.K.; Chung, M.J.; Cho, H.B.; Cho, B.H.; Jung, Y.G. Detection of maxillary sinus fungal ball via 3-D CNN-based artificial intelligence: Fully automated system and clinical validation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J. Definitions of fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2000, 33, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshazo, R.D. Syndromes of invasive fungal sinusitis. Med Mycol. 2009, 47, S309–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, A.A.; Enani, M.; Mahasin, Z.; Al-Omran, K. Chronic invasive aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses in immunocompetent hosts from Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001, 65, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, W.; Doffinger, R.; Shelton, F.; Sproson, E.; Ismail-Koch, H.; Lund, V.J.; Harries, P.G.; Eren, E.; Salib, R.J. A Novel Insight into the Immunologic Basis of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis. Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 7, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montone, K.T. Pathology of Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2016, 10, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asoegwu, C.N.; Oladele, R.O.; Kanu, O.O.; Nwawolo, C.C. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in Nigeria: Challenges of management. Int. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 6, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, I.; Alsaleh, S.; Alqaryan, S.; Assiri, H.; Alsukayt, M.; Alswayyed, M.; Sumaily, I. Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: A Case Series and Literature Review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100 (Suppl. S5), 720S–727S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Gonzalez, J.L.; Santos-Santillana, K.M.; Maldonado-Chapa, F.; Morales-Del Angel, J.A.; Gomez-Castillo, P.; Cortes-Ponce, J.R. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. Ann. Med. Surg 2021, 72, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Rasheed, A.; Awan, M.R.; Hameed, A. Aspergillus Infection of Paranasal Sinuses. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2010, 5, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halderman, A.; Shrestha, R.; Sindwani, R. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis: An evolving approach to management. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, D.B.; Walsh, T.J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Stevens, D.A.; Edwards, J.E.; Calandra, T.; Pappas, P.G.; Maertens, J.; Lortholary, O.; Kauffman, C.A.; et al. Revised Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhya, A.K. Grocott methenamine silver positivity in Neutrophils. J. Cytol. 2019, 36, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.; Sivalingam, V.; Tang, H.M.; Montgomery, J.M.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Halliday, C.L. Molecular Diagnostics for Invasive Fungal Diseases: Current and Future Approaches. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeican, I.I.; Barbu Tudoran, L.; Florea, A.; Flonta, M.; Trombitas, V.; Apostol, A.; Dumitru, M.; Aluaș, M.; Junie, L.M.; Albu, S. Chronic Rhinosinusitis: MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Microbiological Diagnosis and Electron Microscopy Analysis; Experience of the 2nd Otorhinolaryngology Clinic of Cluj-Napoca, Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudisa, R.; Harchand, R.; Rudramurthy, S.M. Nucleic-Acid-Based Molecular Fungal Diagnostics: A Way to a Better Future. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Han, S.; Lv, L.; Li, L. Next-Generation Sequencing Applications for the Study of Fungal Pathogens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbrah, G.S.; Jain, S.; Singh, S.; Fatima, Z.; Hameed, S. Diagnostic Efficacy of LAMP Assay for Human Fungal Pathogens: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2023, 17, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Pereira, J.; Fernandes, F.; Araújo, R.; Springer, J.; Loeffler, J.; Buitrago, M.J.; Pais, C.; Sampaio, P. Multiplex PCR Based Strategy for Detection of Fungal Pathogen DNA in Patients with Suspected Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Chakrabarti, A. Epidemiology and medical mycology of fungal rhinosinusitis. Otorhinolaryngol. Clin. Int. J. 2009, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, V.; Peter, J.; Michael, J.S.; Thomas, M.; Irodi, A.; Rajshekhar, V. Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in Patients With Immunocompetence: A Review. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.F.; Thompson, G.R.; Denning, D.W.; Fishman, J.A.; Hadley, S.; Herbrecht, R.; Bennett, J.E. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e1–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.J.; Anaissie, E.J.; Denning, D.W.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Morrison, V.A.; Segal, B.H.; Steinbach, W.J.; Stevens, D.A.; et al. Treatment of Aspergillosis: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, V.; Maheswaran, S.; Ebenezer, J.; Mathews, S. Current therapeutic protocols for chronic granulomatous fungal sinusitis. Rhinol. J. 2015, 53, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krishna, S.; Ashok, V.; Abdulla, S.; John, R.; Ramalingam, P. Unmasking the Fungal Menace: A Case Report of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of Maxilla. Sinusitis 2025, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010004

Krishna S, Ashok V, Abdulla S, John R, Ramalingam P. Unmasking the Fungal Menace: A Case Report of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of Maxilla. Sinusitis. 2025; 9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrishna, Swathi, Vivekanand Ashok, Shahseena Abdulla, Rosmy John, and Prathap Ramalingam. 2025. "Unmasking the Fungal Menace: A Case Report of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of Maxilla" Sinusitis 9, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010004

APA StyleKrishna, S., Ashok, V., Abdulla, S., John, R., & Ramalingam, P. (2025). Unmasking the Fungal Menace: A Case Report of Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis of Maxilla. Sinusitis, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010004