Association Between Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-Specific IgE and House-Dust-Mite-Specific IgE in Brazilian Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

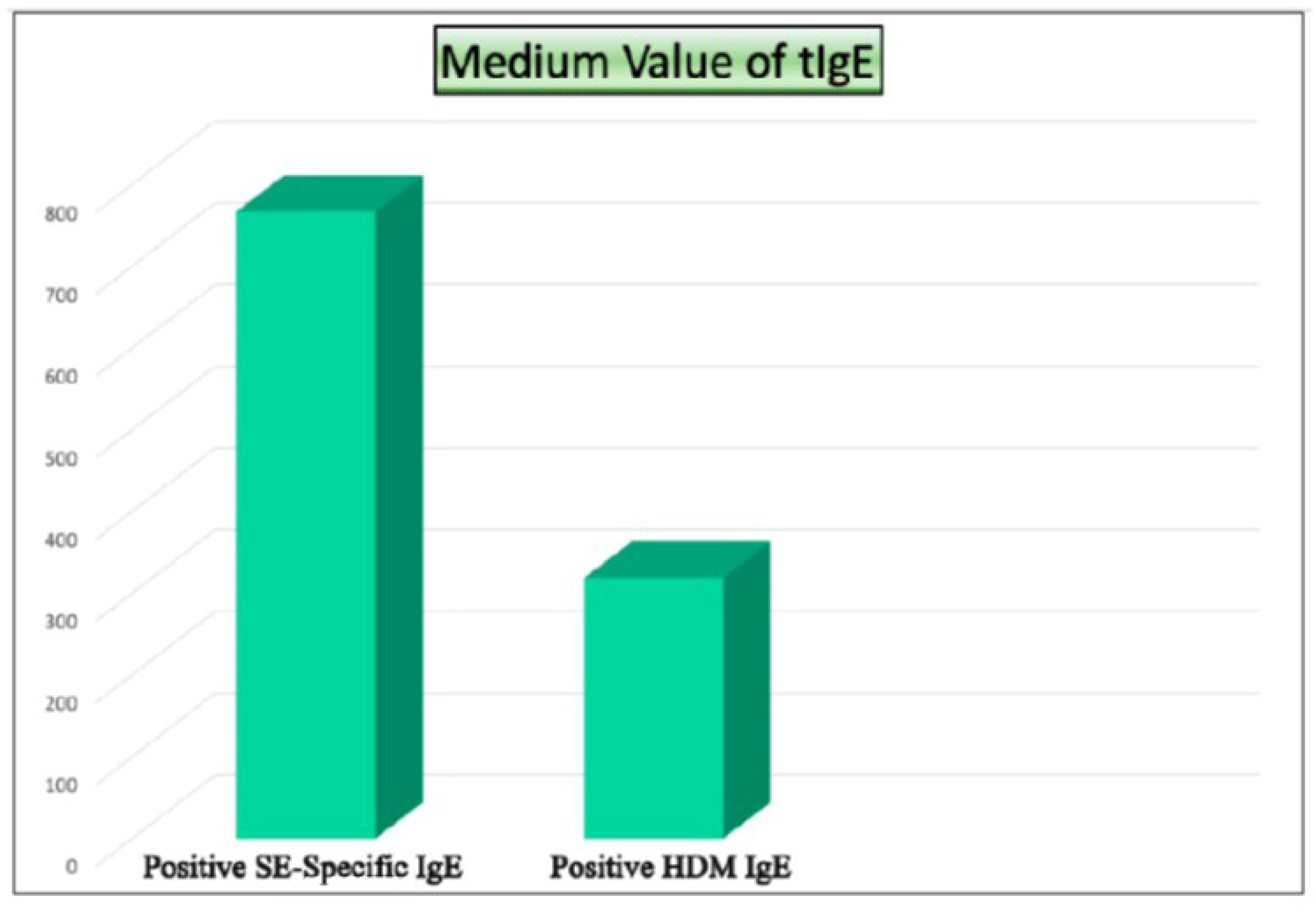

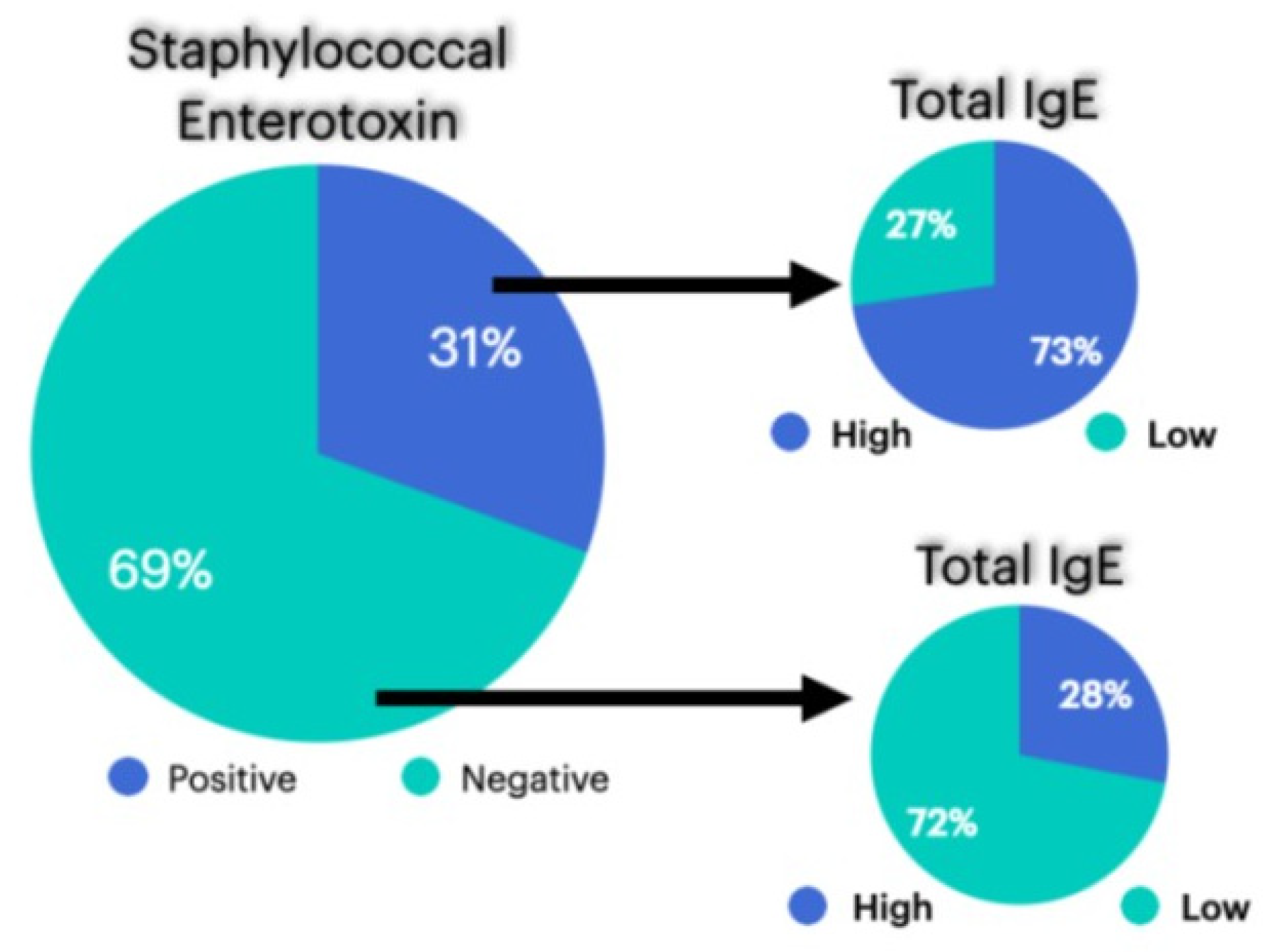

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielik, L.P.; Mielnik-Niedzielska, G.; Kasprzyk, A.; Stankiewicz, T.; Niedzielski, A. Health-Related Quality of Life Assessed in Children with Chronic Rhinitis and Sinusitis. Children 2021, 8, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caminha, G.P.; Melo, J.T., Jr.; de Hopkins, C.; Pizzichini, E.; Pizzichini, M.M.M. SNOT-22: Adaptação cultural e propriedades psicométricas para a língua portuguesa falada no Brasil. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 78, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.S.; Prince, A.A.; Maxfield, A.Z.; Corrales, C.E.; Shin, J.J. The Sinonasal Outcome Test–22 or European Position Paper: Which Is More Indicative of Imaging Results? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 164, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L. Comparison of different endoscopic scoring systems in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: Reliability, validity, responsiveness and correlation. Rhinol. J. 2017, 55, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasztura, M.; Richard, A.; Bempong, N.-E.; Loncar, D.; Flahault, A. Cost-effectiveness of precision medicine: A scoping review. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Zele, T.; Gevaert, P.; Watelet, J.B.; Claeys, G.; Holtappels, G.; Claeys, C.; van Cauwenberge, P.; Bachert, C. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and IgE antibody formation to enterotoxins is increased in nasal polyposis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 114, 978–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Zhang, L.; Gevaert, P. Current and future treatment options for adult chronic rhinosinusitis: Focus on nasal polyposis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, M.; Perrotta, F.; Nicolai, A.; Maffucci, R.; Pratillo, A.; Mollica, M.; Bianco, A.; Calabrese, C. Staphylococcus Aureus in Chronic Airway Diseases: An Overview. Respir. Med. 2019, 155, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chegini, Z.; Didehdar, M.; Khoshbayan, A.; Karami, J.; Yousefimashouf, M.; Shariati, A. The role of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Zhang, N.; Holtappels, G.; De Lobel, L.; van Cauwenberge, P.; Liu, S.; Lin, P.; Bousquet, J.; Van Steen, K. Presence of IL-5 protein and IgE antibodies to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins in nasal polyps. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 962–968.e9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujieda, S.; Imoto, Y.; Kato, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Tsutsumiuchi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kidoguchi, M.; Takabayashi, T. Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol Int. 2019, 68, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.L.; Borish, L. Chronic sinusitis pathophysiology: The role of allergy. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-K.; Yoo, S.-J.; Kim, T.S.; Kim, B.-K.; Jang, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, K. Differences between Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage and IgE-sensitization to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin on risk factors and effects in adult population. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westwood, M.; Ramaekers, B.; Lang, S.; Armstrong, N.; Noake, C.; de Kock, S.; Joore, M.; Severens, J.; Kleijnen, J. ImmunoCAP® ISAC and Microtest for multiplex allergen testing in people with difficult to manage allergic disease: A systematic review and cost analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 20, 1–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, P.; Dortas Junior, S.D.; Valle, S.O.R.; Novello Ferreira, N.; da Cruz, F.C.; Ferraiolo, P.N.; Elabras Filho, J. Associação entre IgE específicas para enterotoxinas estafilocócicas (EE), ácaros e IgE total (IgEt) em pacientes com rinossinusite crônica (RSC). Arq. Asma Alerg. Imunol. 2019, 3 (Suppl. S1), S184, XLVI Brazilian Congress of Allergy and Immunology. Available online: http://aaai-asbai.org.br/default.asp?ed=129 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ho, J.; Earls, P.; Harvey, R.J. Systemic biomarkers of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund–Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 5,3 | 76 | Y | N | N | 04 | 31 |

| 2 | M | 16 | 62 | N | Yes, 1 | N | 06 | 40 |

| 3 | M | 15 | 63 | Y | Yes, 1 | N | 02 | 08 |

| 4 | M | 13 | 45 | Y | Yes, 1 | Y | 04 | 26 |

| 5 | M | 66 | 25 | N | N | N | 02 | 12 |

| 6 | F | 10 | 68 | N | N | N | 03 | 23 |

| 7 | F | 8,0 | 68 | Y | N | N | 02 | 30 |

| 8 | M | 65 | 51 | N | N | N | 02 | 12 |

| 9 | F | 24 | 34 | N | N | N | 03 | 19 |

| 10 | M | 87 | 56 | N | N | N | 04 | 27 |

| 11 | F | 9,0 | 46 | N | N | N | 02 | 21 |

| 12 | F | 6,4 | 55 | Y | N | N | 03 | 13 |

| 13 | F | 33 | 25 | N | N | N | 01 | 09 |

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund–Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | M | 25 | 20 | N | N | N | 02 | 28 |

| 15 | M | 68 | 73 | Y | N | N | 03 | 32 |

| 16 | M | 86,3 | 59 | N | N | N | 04 | 46 |

| 17 | M | 25 | 40 | Y | N | N | 03 | 36 |

| 18 | M | 60 | 39 | Y | N | N | 02 | 29 |

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund–Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | M | 305 | 44 | Y | Yes, 5 | Y | 02 | 37 |

| 20 | F | 360 | 14 | N | Yes, 5 | N | 01 | 32 |

| 21 | F | 249 | 54 | Y | Yes, 1 | Y | 03 | 10 |

| 22 | F | 214 | 40 | N | N | N | 02 | 20 |

| 23 | F | 234 | 50 | N | N | N | 02 | 31 |

| 24 | F | 544 | 58 | Y | N | N | 01 | 27 |

| 25 | M | 325 | 64 | N | N | N | 02 | 32 |

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund–Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | F | 487 | 40 | Y | Yes, 1 | N | 05 | 65 |

| 27 | M | 165 | 55 | N | N | N | 04 | 41 |

| 28 | F | 914 | 26 | N | N | N | 04 | 55 |

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund–Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | M | 173 | 62 | Y | Yes, 6 | Y | 08 | 73 |

| 30 | M | 149 | 43 | N | Yes, 2 | N | 06 | 68 |

| 31 | F | 3040 | 58 | Y | Yes, 1 | N | 04 | 71 |

| 32 | F | 1030 | 32 | N | N | N | 02 | 41 |

| 33 | F | 180 | 60 | N | N | N | 02 | 35 |

| Patient | Sex | t-IgE | Age | Asthma | Previous Surgeries | AERD | Lund Kennedy Score | SNOT-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | F | 92 | 65 | N | Yes, 1 | Y | 06 | 43 |

| 35 | M | 84 | 56 | N | N | N | 04 | 48 |

| 36 | F | 53 | 44 | Y | N | N | 04 | 27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos, P.; Dortas Junior, S.D.; Valle, S.O.R.; Novello Ferreira, N.; da Cruz, F.C.; Ferraiolo, P.N.; Elabras Filho, J. Association Between Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-Specific IgE and House-Dust-Mite-Specific IgE in Brazilian Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Sinusitis 2025, 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010005

Campos P, Dortas Junior SD, Valle SOR, Novello Ferreira N, da Cruz FC, Ferraiolo PN, Elabras Filho J. Association Between Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-Specific IgE and House-Dust-Mite-Specific IgE in Brazilian Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Sinusitis. 2025; 9(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos, Priscilla, Sérgio Duarte Dortas Junior, Solange Oliveira Rodrigues Valle, Nathalia Novello Ferreira, Fabiana Chagas da Cruz, Priscila Novaes Ferraiolo, and José Elabras Filho. 2025. "Association Between Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-Specific IgE and House-Dust-Mite-Specific IgE in Brazilian Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps" Sinusitis 9, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010005

APA StyleCampos, P., Dortas Junior, S. D., Valle, S. O. R., Novello Ferreira, N., da Cruz, F. C., Ferraiolo, P. N., & Elabras Filho, J. (2025). Association Between Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-Specific IgE and House-Dust-Mite-Specific IgE in Brazilian Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Sinusitis, 9(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9010005