Optimizing SAW Device Performance Using Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate Substrates

Abstract

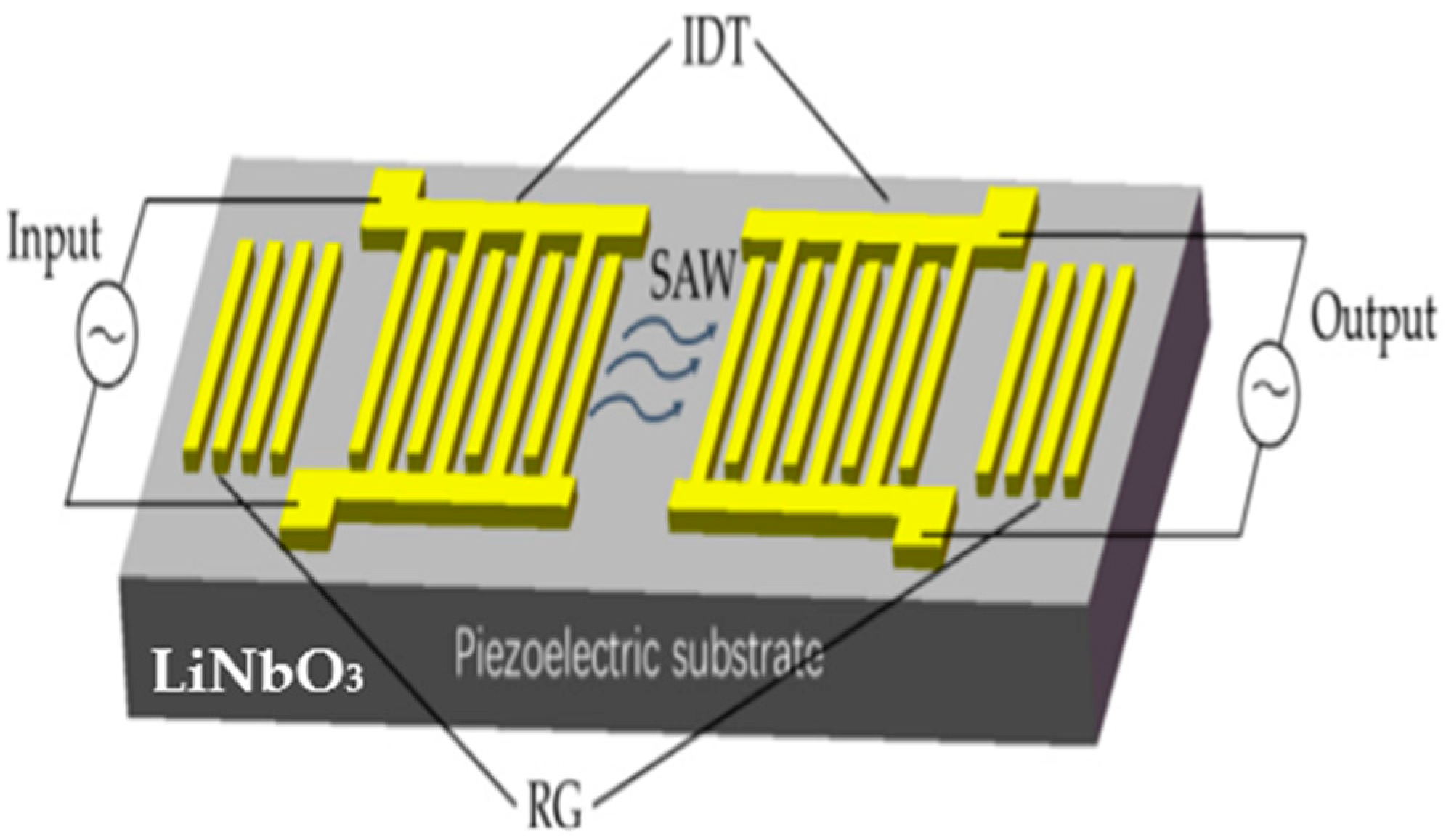

1. Introduction

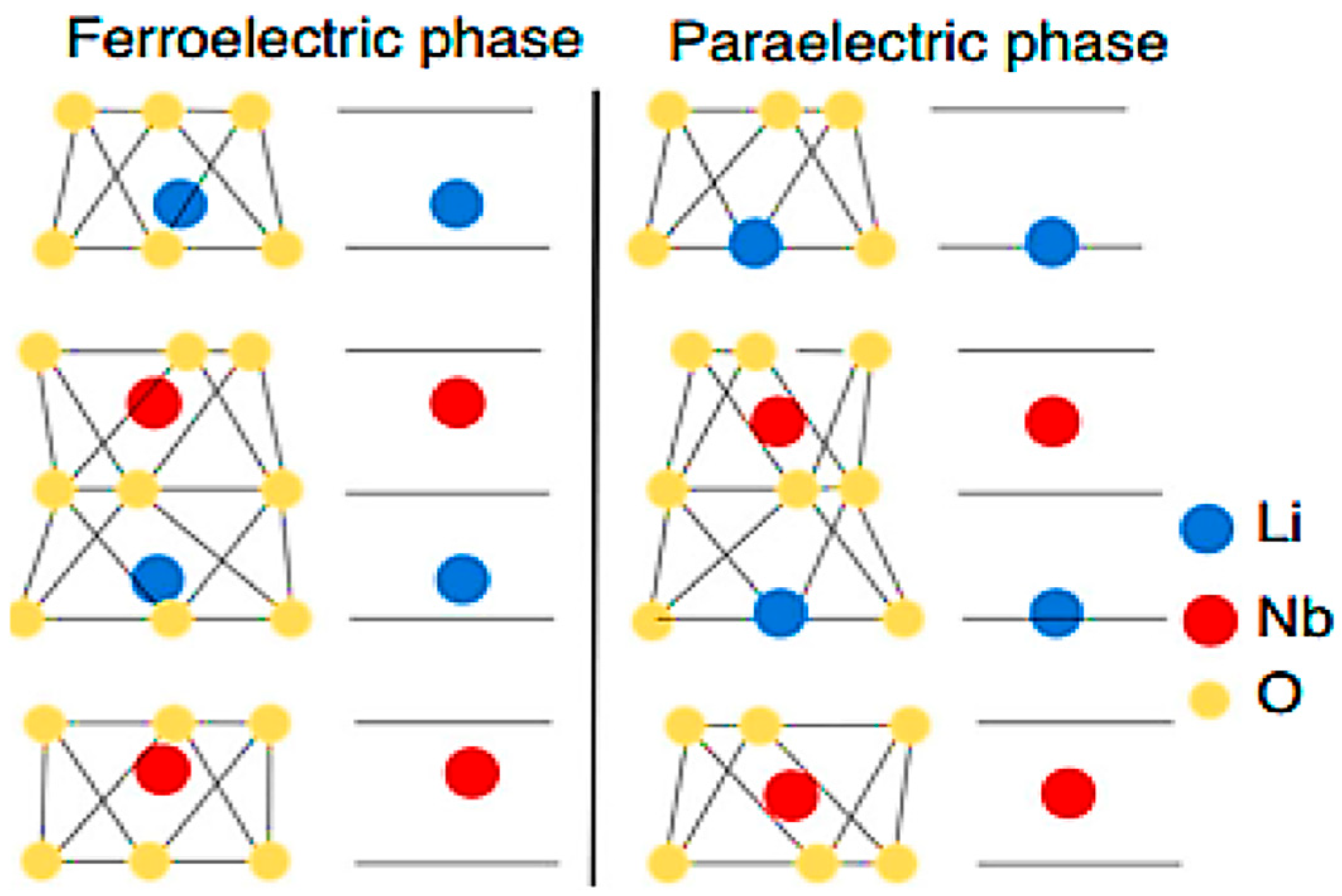

2. Materials and Methods

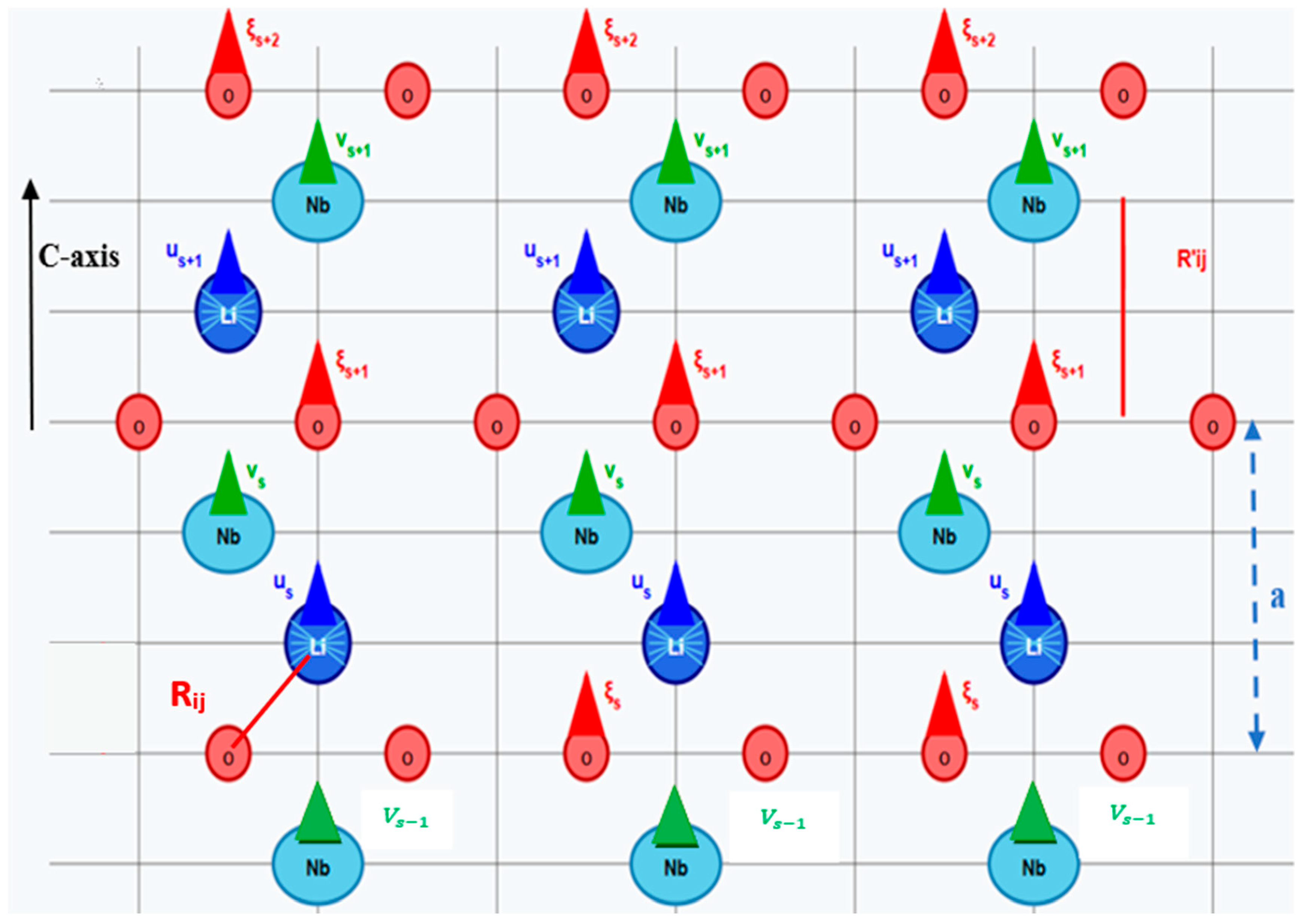

2.1. Previous Theoretical Model (Th1)

2.2. Our Theoretical Approach (Th2)

2.3. Estimation of the Inverse Quality Factor, Electrical Conductivity, and Equivalent Mechanical Strength

2.3.1. Estimation of Electrical Conductivity

2.3.2. Titanium-Doping Model

2.3.3. Modeling of the Inverse Quality Factor

2.3.4. Equivalent Mechanical Resistance

3. Results and Discussion

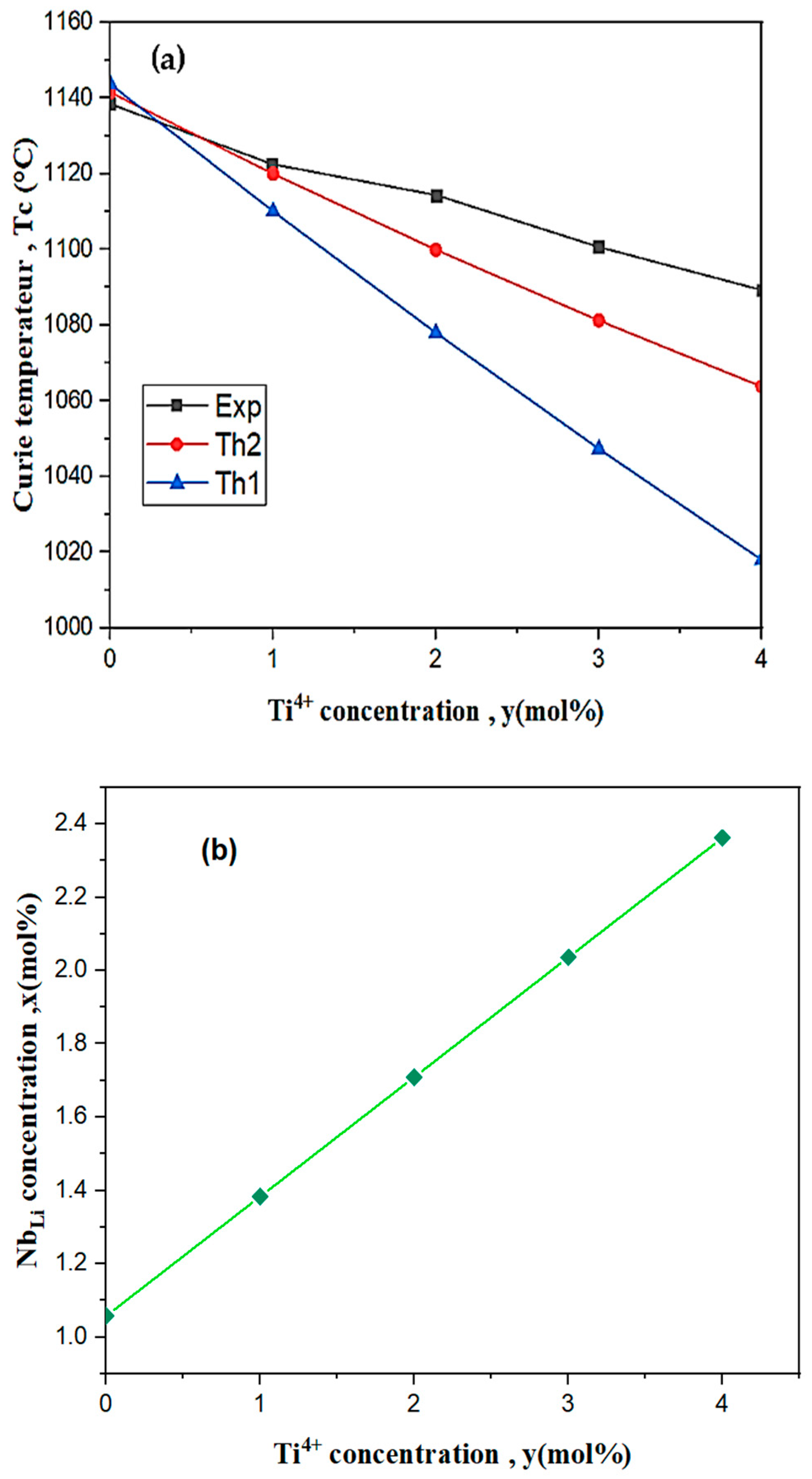

3.1. Curie Temperature of Titanium-Doped Niobate

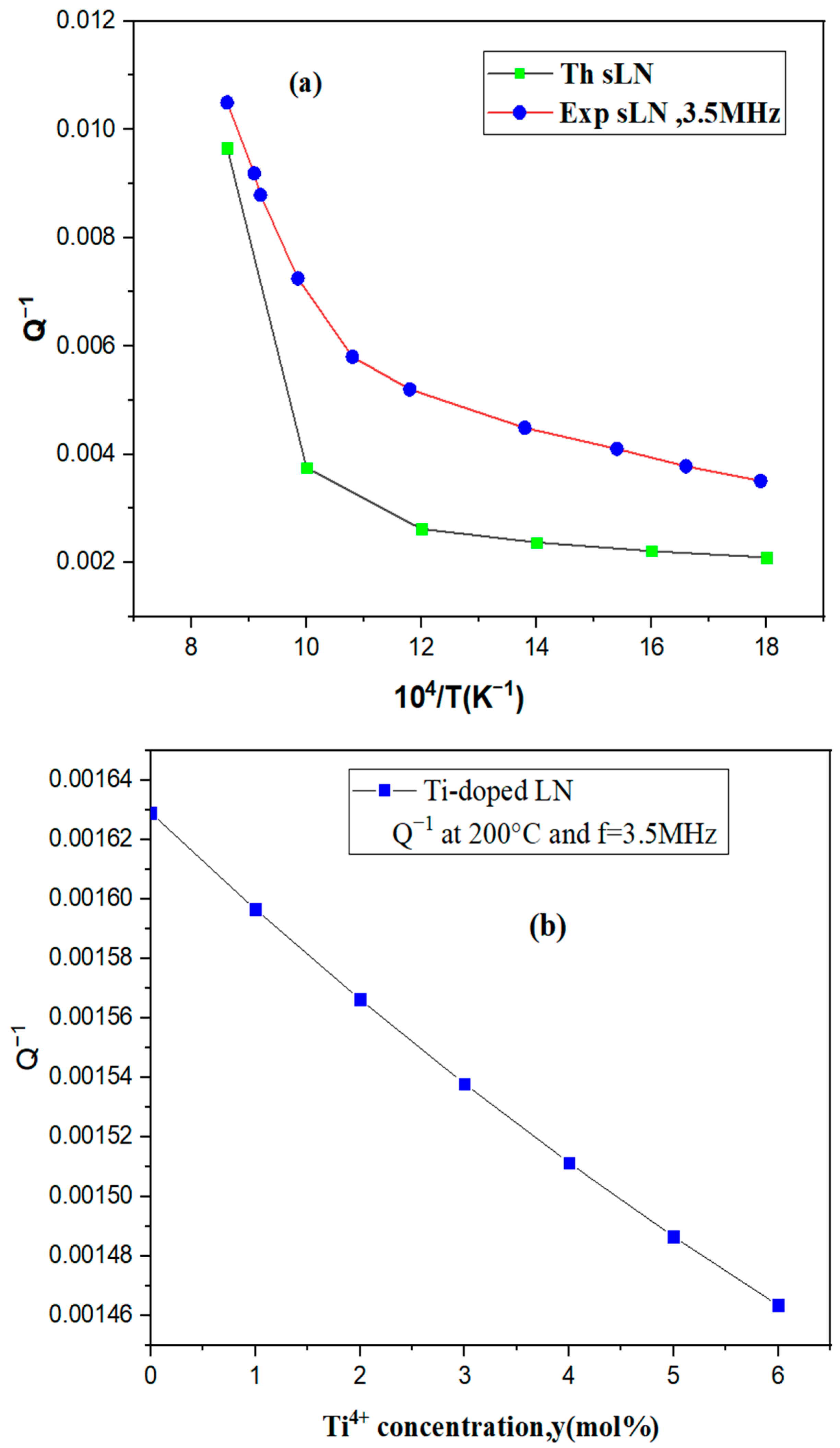

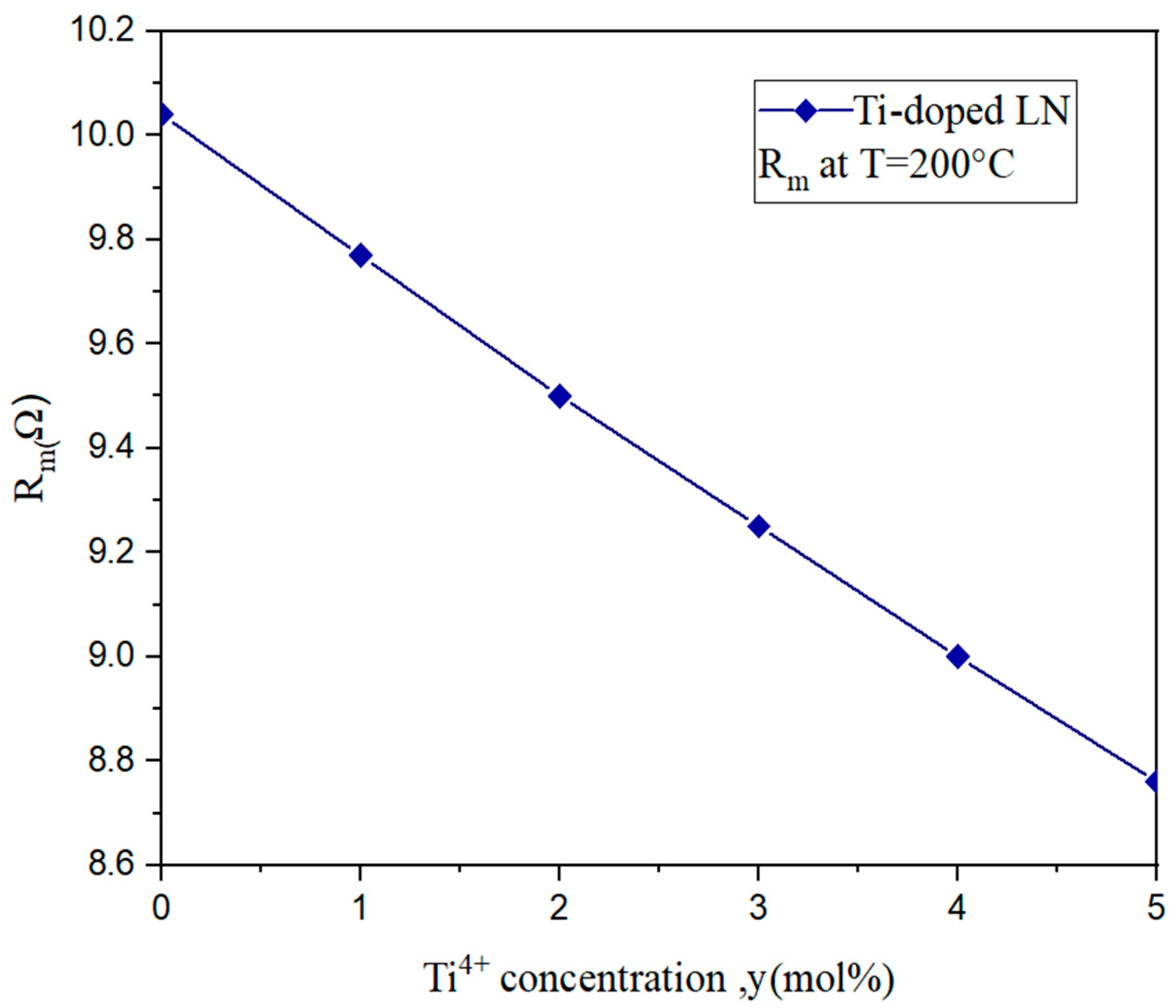

3.2. Inverse of the Quality Factor and Mechanical Strength of Lithium Niobate of Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Si, J.; Liang, S.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; et al. Lithium Niobate Crystal Preparation, Properties, and Its Application in Electro-Optical Devices. Inorganics 2025, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wei, H.; Tang, G.; Cao, B.; Chen, K. Advanced Crystallization Methods for Thin-Film Lithium Niobate and Its Device Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatnikov, M.; Makarova, O.; Kadetova, A.; Sidorov, N.; Teplyakova, N.; Biryukova, I.; Tokko, O. Structure, Optical Properties and Physicochemical Features of LiNbO3:Mg,B Crystals Grown in a Single Technological Cycle: An Optical Material for Converting Laser Radiation. Materials 2023, 16, 4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wan, Q. Lithium niobate/lithium tantalate single-crystal thin films for post-Moore era chip applications. Moore More 2024, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, R. The historical development of the Czochralski method. J. Cryst. Growth 2014, 401, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liang, H.; Luo, R.; Jiang, W.C.; Zhang, X.-C.; Lin, Q. Nonlinear optical oscillation dynamics in high-Q lithium niobate microresonators. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 13504–13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatnikov, M.N.; Kadetova, A.V.; Smirnov, M.V.; Sidorova, O.V.; Vorobev, D.A. Nonlinear optical properties of lithium niobate crystals doped with alkaline earth and rare earth elements. Opt. Maters 2022, 131, 112631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Bo, F.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, J. Advances in on-chip photonic devices based on lithium niobate on insulator. Photon. Res. 2020, 8, 1910–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofahl, C.; Ganschow, S.; Bernhardt, F.; El Azzouzi, F.; Sanna, S.; Fritze, H.; Schmidt, H. Li-diffusion in lithium niobate-tantalate solid solutions. Solid State Ion. 2024, 409, 116514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriniz, M.; El Bouayadi, O.; El Barbri, N.; Maaider, K.; Khalil, A. The impact of the simultaneous presence of Li and Nb(Ta) vacancies in the defect structure of pure LiBO3 (B = Nb, Ta) on the curie temperature. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 469, 00007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, N.V.; Teplyakova, N.A.; Makarova, O.V.; Palatnikov, M.N.; Titov, R.A.; Manukovskaya, D.V.; Birukova, I.V. Boron Influence on Defect Structure and Properties of Lithium Niobate Crystals. Crystals 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, A.; Marques, J.G. Unveiling the Defect Structure of Lithium Niobate with Nuclear Methods. Crystals 2021, 11, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shi, E.; Wang, S.; Lu, Z.; Cui, S.; Wang, L.; Zhong, W. Domain structures and etching morphologies of lithium niobate crystals with different Li contents grown by TSSG and double crucible Czochralski method. Cryst. Res. Technol. J. Exp. Ind. Crystallogr. 2004, 39, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Bhaumik, I.; Ganesamoorthy, S.; Karnal, A.; Gupta, P.; Swami, M.; Patel, H.; Sinha, A.; Upadhyay, A. Study of structural defects and crystalline perfection of near stoichiometric LiNbO3 crystals grown from flux and prepared by VTE technique. J. Mol. Struct. 2014, 1075, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Bhaumik, I.; Ganesamoorthy, S.; Bright, R.; Soharab, M.; Karnal, A.K.; Gupta, P.K. Control of Intrinsic Defects in Lithium Niobate Single Crystal for Optoelectronic Applications. Crystals 2017, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Joo, K.; Shin, K.-B.; Auh, K.-H. Single Crystal Growth of Optic-Grade LiNbO3 Using a Floating Zone Technique. In Proceedings of the Korea Association of Crystal Growth Conference, Gyeongju, Korea, 1 September 1998; The Korea Association of Crystal Growth: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1998; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Dena, O.; Fierro-Ruiz, C.D.; Villalobos-Mendoza, S.D.; Carrillo Flores, D.M.; Elizalde-Galindo, J.T.; Farías, R. Lithium Niobate Single Crystals and Powders Reviewed—Part I. Crystals 2020, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaider, K.; Masaif, N.; Khalil, A. Stoichiometry-related defect structure in lithium niobate and lithium tantalate. Indian J. Phys. 2021, 95, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaryan, F.P.; Feigelson, R.S.; Petrosyan, A.M. An approach to the defect structure analysis of lithium niobate single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 85, 8079–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaider, K.; Jennane, A.; Khalil, A.; Masaif, N. A new analytical description in C2+ doped LiBO3 C (Ni, Zn…); B (Nb, Ta). Indian J. Phys. 2012, 86, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Dong, B.; Hu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, S. High-Frequency Surface Acoustic Wave Resonator with Diamond/AlN/IDT/AlN/Diamond Multilayer Structure. Sensors 2022, 22, 6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, G.; Liao, W.; Zou, Y.; Chu, T.; Fu, Q.; Dong, W. Advancing inorganic electro-optical materials for 5 G communications: From fundamental mechanisms to future perspectives. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Third-Degree Equation: Cardan’s Method. Available online: https://fr.wikiversity.org/wiki/Équation_du_troisième_degré/Méthode_de_Cardan (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Escofier, J.P. Galois Theory; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 204. [Google Scholar]

- Iyi, N.; Kitamura, K.; Izumi, F.; Yamamoto, J.K.; Hayashi, T.; Asano, H.; Kimura, S. Comparative study of defect structures in lithium niobate with different compositions. J. Solid State Chem. 1992, 101, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfelder, A.; Shi, J.; Fielitz, P.; Borchardt, G.; Becker, K.D.; Fritze, H. Electrical and electromechanical properties of stoichiometric lithium niobate at high-temperatures. Solid State Ion. 2012, 225, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichy-Rács, É.; Hurskyy, S.; Yakhnevych, U.; Gaczyński, P.; Ganschow, S.; Fritze, H.; Suhak, Y. Influence of Li-Stoichiometry on Electrical and Acoustic Properties and Temperature Stability of Li(Nb,Ta)O3 Solid Solutions up to 900 °C. Phys. Status Solidi 2025, 222, 2300962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.D.; Bradley, P.D.; Wartenberg, S.; Ruby, R.C. Modified Butterworth-Van Dyke circuit for FBAR resonators and automated measurement system. In Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 22–25 October 2000; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 863–868. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, L.; Kochhar, A.; Vidal-Álvarez, G.; Piazza, G. Impact of frequency mismatch on the quality factor of large arrays of X-cut lithium niobate MEMS resonators. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2020, 29, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriniz, M.; Maaider, K.; El Barbri, N.; Khalil, A.; Amkor, A. Advanced simulations of the Curie temperature of the density in pure and MgO-doped LiNbO3. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Fez, Morocco, 15–16 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, C.; Nozawa, J.; Fujiwara, K.; Uda, S. Effect of point defects on Curie temperature of lithium niobate. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1143.7 | 1141.53 | 1138.47 | 5.23 | 3.06 |

| 1 | 1110.07 | 1119.98 | 1122.54 | −12.47 | −2.56 |

| 2 | 1077.98 | 1099.93 | 1114.34 | −36.36 | −14.41 |

| 3 | 1047.32 | 1081.23 | 1100.68 | −53.36 | −19.45 |

| 4 | 1017.97 | 1063.76 | 1089.29 | −71.32 | −25.53 |

| c.LN | s.LN | |

|---|---|---|

| 3.5 MHz | 3.5 MHz | |

| (1.45 ± 0.07) eV | (1.53 ± 0.07) eV | |

| (8.90 ± 0.05)·10−3 | (5.66 ± 0.05)·10−3 | |

| 0.57 | 0.57 | |

| (0.10 ± 0.04) eV | (0.14 ± 0.04) eV | |

| (1.2 ± 0.1)·10−3 | (1.8 ± 0.1)·10−3 | |

| (5.75 ± 0.07)·105 SKm−1 | (1.16 ± 0.08)·106 SKm−1 |

| c.LN (r = 0.9372) | LN:Ti | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 104/T(K−1) | Q−1 | Concentration of Ti4+ (mol%) | Q−1 at 200 °C |

| 9.43 | 0.005411 | 0 | 0.00162896 |

| 10 | 0.004368 | 1 | 0.00159652 |

| 12 | 0.003277 | 2 | 0.00156617 |

| 14 | 0.002813 | 3 | 0.00153781 |

| 16 | 0.002463 | 4 | 0.0015113 |

| 18 | 0.002190 | 5 | 0.00148654 |

| 20 | 0.001975 | 6 | 0.00146342 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beriniz, M.; Maaider, K.; El Barbri, N.; Amkor, A.; Khalil, A. Optimizing SAW Device Performance Using Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate Substrates. Optics 2025, 6, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040063

Beriniz M, Maaider K, El Barbri N, Amkor A, Khalil A. Optimizing SAW Device Performance Using Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate Substrates. Optics. 2025; 6(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeriniz, Mohamed, Kamal Maaider, Noureddine El Barbri, Ali Amkor, and Abdelghani Khalil. 2025. "Optimizing SAW Device Performance Using Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate Substrates" Optics 6, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040063

APA StyleBeriniz, M., Maaider, K., El Barbri, N., Amkor, A., & Khalil, A. (2025). Optimizing SAW Device Performance Using Titanium-Doped Lithium Niobate Substrates. Optics, 6(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt6040063