Abstract

Photons in interferometers manifest the functional ability to simultaneously navigate both paths through the device, but eventually appear at only one outlet. How this relates to the physical behaviour of the particle is still ambiguous, even though mathematical representation of the problem is adequate. This paper applies a non-local hidden-variable (NLHV) solution, in the form of the Cordus theory, to explain photon path dilemmas in the Mach–Zehnder (MZ) interferometer. The findings suggest that the partial mirrors direct the two reactive ends of the Cordus photon structures to different legs of the apparatus, depending on the energisation state of the photon. Explanations are provided for a single photon in the interferometer in the default, open-path, and sample modes. The apparent intelligence in the system is not because the photon knows which path to take, but rather because the MZ interferometer is a finely-tuned photon-sorting device that auto-corrects for randomness in the frequency phase to direct the photon to a specific detector. The principles also explain other tunnelling phenomena involving barriers. Thus, navigation dilemmas in the MZ interferometer may be explained in terms of physical realism after all.

1. Introduction

Particles show attributes of wave-particle duality behaviour in interferometer devices. The behaviour manifests as a functional ability of the photon to simultaneously navigate both paths through the device, but eventually appear at only one outlet. This behaviour may be functionally represented in quantum formulations, but how this relates to the physical behaviour of the particle is still ambiguous. Indeed, the level of residual ambiguity depends on the perspective taken, and more mathematical worldviews may not perceive that there is anything left unexplained. Nonetheless, from the perspective of classical physics, and also the philosophical position of physical realism, there are conceptual difficulties reconciling the path navigation behaviour with notions of particle composition. By this we do not mean that there is any lack of mathematical representation of the problem, but rather that there is value in seeking ontologically richer perspectives grounded in physical realism.

This paper extends previous work by applying a non-local hidden-variable (NLHV) solution, in the form of the Cordus theory [], to explain photon path dilemmas. The application is primarily to the Mach–Zehnder interferometer, although the principles generalise to explain tunnelling.

2. Existing Approaches

Wave theory explains the situation as the interference of two waves. However, that only applies to beams of light, whereas the empirical reality is that the behaviour also exists for individual photons. Classical wave theory cannot explain this. Quantum mechanics (QM) began with the idea of light being made of corpuscles, hence photons. Subsequent developments of quantum field theory (QFT) provided a mathematical representation of the photon as a set of quantum oscillators, as opposed to a particle with a specific position []. The operation of an interferometer, a likewise double-slit device, is readily accommodated by QFT, even for a single photon. The photon is represented as having two modes, which correspond to the two legs of the interferometer. Dirac [] similarly noted that “each photon [goes] partly into each of the two components” (p9). Thus, from the QFT perspective, the photon is not simply a point particle, and is more than an electromagnetic plane wave and wave packet. So, from within QFT, the navigation of the photon through the simple interferometer does not present any difficulty. Nonetheless, QFT is not a complete theory (gravitation is excluded), and the interferometer behaviour does present a conundrum when viewed more generally. Specifically, there are ontological problems about the nature of photon identity from a realist perspective. Physical realism is the assumption, based on experience in the everyday world, that observed phenomena have underlying physical mechanisms []. From this perspective both classical and quantum physics are incomplete descriptions of photon path behaviour, despite having acknowledged strengths in other respects.

Other explanations for the path dilemma in wave-particle duality are intelligent photons and parallel universes, but both have difficulties. The first assumes some intelligence in the photon: that photons know when a path is blocked, without even going down it (e.g., Mach–Zehnder interferometer), and adapt their behaviour in response to the presence of an observer (e.g., Schrodinger’s Cat, Zeno effect). This also raises philosophical problems with choice and the power of the observer to affect the physical world and its future merely by looking at it (contextual measurement). Thus, the action of observation would affect the locus taken by a photon, and therefore the outcome. This concept is sometimes generalised to the universe as a whole. The second explanation is the metaphysical idea of parallel universes or many worlds, i.e., that each statistical outcome that does not occur in this universe does in another []. From the perspective of physical realism, it is problematic that these other universes are unobservable. It also means that the theory cannot be verified. Nor is it clear what keeps track of the information content of the vast number of universes that such a system would generate. Both these explanations are convenient ways of comprehending the practicalities of wave-particle duality, but they sidestep the real issues.

Finally, there is the hidden variable sector of physics. This is based on the assumption that particles have internal sub-structures that provide the mechanisms for the observed behaviours. Although this principle is consistent with the expectations of physical realism, the sector as a whole has been unproductive at developing useful theories. There was a historical attempt to explain path dilemmas assuming hidden-variables in the form of the de Broglie-Bohm theory of the pilot wave [,]. However, it is debatable whether this really solves the problem. Nor has the concept progressed to form a broader theory of physics that could explain other phenomena.

The above treatment of the quantum perspective of photons is brief and is not intended to encompass the “true nature” of the photon (if that is even possible). Hence, the question of non-localisation of photons [,], or whether an effective mass emerges for massless particles generally when they interact [], is skipped over here. By this we do not mean that there is any lack of value in considering the problem from the localisation perspective, or any lack of mathematical representation of the problem via quantum field theory, but rather that there is value in the ontologically different perspectives that can be provided by other theories such as NLHV theory. A NLHV theory automatically assumes non-locality occurs, and, hence, implicitly expects the photon to exist in more than one location. Furthermore, the specific NLHV theory explored here has a field component with multiple oscillators [] and, hence, has elements that are not dissimilar to QFT. While NLHV theories may be lacking in mathematical formalism, they do provide new insights. The various existing theories of physics have historically benefited from findings from each other.

3. Approach

The purpose of this work was to apply the Cordus theory to the photon path problem in interferometers. This is a type of non-local hidden-variable (NLHV) theory, and, therefore, has an explicit link between the functional attributes of the particle and a proposed inner causality. For the origin of this NLHV concept and its application to the double-slit device, see []. The theory also provides a derivation of optical laws (reflection, refraction, and Brewster’s angle) [] and a description of the processes of photon emission and absorption [,], conversion of photons to electron-positron in pair production [], annihilation of matter-antimatter back to photons [], the asymmetrical genesis production sequence from photons to a matter universe [], and the origin of the finite speed of light [].

The approach taken was a conceptual one, using abductive reasoning. Design principles were used to logically infer the requisite internal structures that would be sufficient to explain the observed path phenomena. While such methods do not give results with the same level of quantitative formulation as mathematical approaches, they do potentially allow new insights. The area under examination was the Mach–Zehnder (MZ) interferometer.

4. Results

4.1. Underpinning Concepts

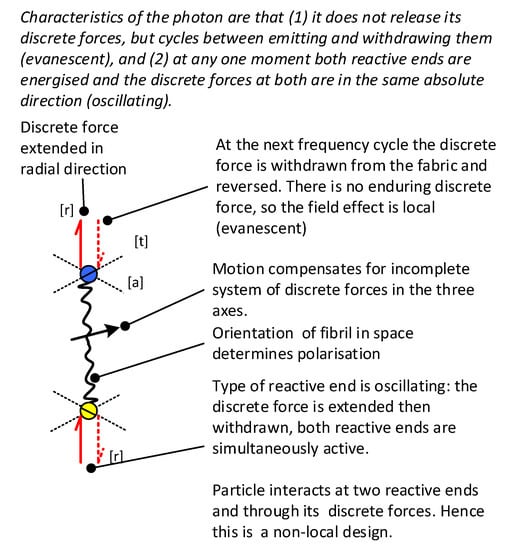

The Cordus theory predicts a specific internal structure for fundamental particles. This comprises two reactive ends, some spatial distance apart, and connected by a fibril. The reactive ends are energised at a frequency, and emit discrete forces at these times []. Each is a type of field oscillator []. This is a NLHV structure but with discrete fields. The structure of the photon is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cordus theory for the internal structure of the photon, its two reactive ends, and its discrete field arrangements. The photon has a pump that shuttles energy outwards into the fabric. Then at the next frequency cycle, it draws the energy out of that field, instantaneously transmits it across the fibril, and expels it at the opposite reactive end. Adapted from [].

The theory requires the photon to have an oscillating system of discrete fields. The discrete forces are ejected from one reactive end and (at the same moment) drawn in at the other. At the next stage in the frequency cycle the directions reverse. Consequently, the photon’s discrete forces are recycled. This also explains why the evanescent field weakens exponentially with distance: because the discrete forces recruit a volume of space []. In contrast, massy particles such as the electron emit discrete forces (the direction provides the charge attribute) and release them into the external environment in a series making up a flux tube. Hence, the electric field has an inverse radius squared relationship because it progresses outwards as a front on the surface of an expanding sphere. The sign convention is for outward motion of discrete forces to correspond to a negative charge, and inward motion to a positive charge. Consequently, this structure also explains why the electric field of the photon reverses its sign.

The explanation of the double-slit experiment is briefly summarised as follows from []. Each reactive end of the photon particle passes cleanly through one slit. The fibril passes through the material between the two slits, but does not interact with it. The particle structure collapses when one of the reactive ends encounters a medium that absorbs its discrete forces, and the whole photon energy then appears at this location. Consequently, whichever reactive end first encounters a detector behind the double-slit device will trigger a detection event. If there is a detector behind each slit, then the variability of the photons’ phase offset results in the events being shared across the detectors. Hence, a single photon appears at one or the other slit, but a stream of them looks like a wave.

However, when only one slit has a detector, then the photon always appears there. This is explained as one of the two reactive ends of the particle passing through each slit, as before. Then the whole particle collapses at whichever reactive end first grounds; this is always the detector since it is first in the locus. No photon structure travels beyond the detector, so no fringes appear on the screen beyond the detector in this case.

4.2. Mach–Zehnder Interferometer

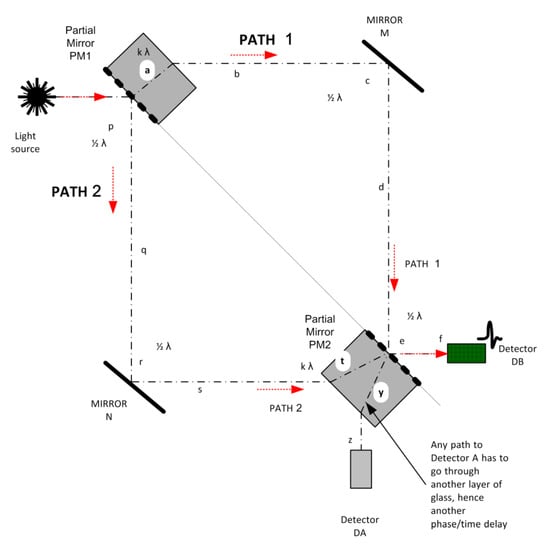

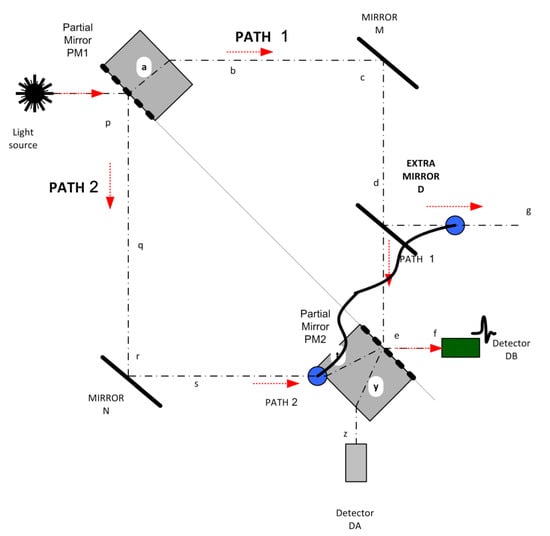

The Mach–Zehnder interferometer also presents with quantum difficulties. It has two detectors at the end of each output path (see Figure 2). The light beam is split into paths 1 and 2 at partial mirror PM1, recombines at partial mirror PM2, and then proceeds to detectors DA and DB.

Figure 2.

Mach–Zehnder interferometer in default mode. The photon appears at DB.

4.2.1. MZ with No Obstructions (Default Mode)

In the default mode, the whole beam selectively appears at one of the detectors. Conventional optical wave theory explains this based on the different reflection and refraction delays encountered on the two paths. The light beam experiences a phase shift of half a wavelength where it reflects off a medium with a higher refractive index (otherwise none), and a constant phase shift k, where it refracts through a denser medium.

The beam on path 1 to detector DB experiences k + ½ + ½ phase-shift (at a, c, and e) (see Figure 2), whereas to reach detector DA requires an additional k (at y). Similarly, the beam on path 2 to detector DB experiences ½ + ½ + k (at p, r, and t). As these are the same, the classical model concludes that the two beams on 1 and 2 result in constructive interference at DB, so the whole output appears there, providing that the optical path lengths around both sides of the interferometer are equal. Similarly, the beam on path 2 into detector DA experiences ½ + ½ + k + k phase-shift (at p, r, t, and v), whereas the 1 beam into DA experiences k + ½ + k phase-shift (at a, c, v). As these differ by half a wavelength, the usual explanation is that the two beams interfere destructively and no light is detected at DA.

This explanation is sufficient for continuous light beams, but not for individual photons.

4.2.2. Quantum Interpretation

This path-selective behaviour also occurs for individual photons, which might be expected to take only one path. If one of the paths is blocked by a mirror that deflects the beam away, then the beam still appears at DB, regardless of which path was blocked. The photon seems to “know” which path was blocked, without actually taking it, and then takes the other. QM successfully quantifies these outcomes [], but leaves the physical explanation unresolved. Explanations such as self-interference, or the existence of virtual particles, add their own problems of interpretation.

4.3. Explanation of MZ Interferometer Behaviour with the Cordus Theory

Considering the Cordus particle with its two ends, it might naively be thought that each reactive end (RE) takes a different path, with the phase difference through the glass at y causing the reactive end to be delayed and, hence, not appearing at detector DA. However, this is unsatisfactory because a decision tree of the path options shows that ¼ of photons should still appear at detector DA even if DA is precisely located relative to DB. The solution involves reconceptualising what happens at the partial mirrors. Specifically, the following mechanisms are proposed (these are lemmas):

- In a full-reflection, i.e., off a mirror, both reactive ends of the photon particle, which are separated by the span, independently reflect off the mirror.

- Reflection does not collapse the particle, i.e., the photon is not absorbed, but rather continues on a locus.

- When encountering a partially reflective surface, e.g., a beam-splitter or partially silvered mirror, the outcome depends on the state (energised vs. dormant) of the reactive end at the time of contact. Specifically:

- 3.1

- A reactive end will reflect off a mirror only if it is predominately in one state, nominally assumed to be the energised state, when it encounters the reflective layer.

- 3.2

- A dormant reactive end passes some way into a reflective layer without reacting. Only if it re-energises within the layer will it be reflected.

- 3.3

- If the reflective layer is thin enough, a dormant reactive end may re-energise on the other side of layer, in which case it is not reflected. Hence, the reactive end tunnels through the layer, and re-energises beyond it.

- 3.4

- The thickness of the layer is therefore predicted to be important, relative to the displacement in space that the reactive end can make. The latter is determined by the velocity and frequency of the particle.

- The orientation of the particle, i.e., polarisation of a photon or spin of an electron, as it strikes the beam-splitter is important in the outcome.

- 4.1

- If the reactive ends strike with suitable timing such that each, in turn, is energised as it engages with the surface, then the whole particle may be reflected. Likewise, if both reactive ends are dormant at their respective engagements, then the whole particle is transmitted.

- 4.2

- It is possible that only one reactive end is reflected and the other transmitted. In this case, the beam-splitter changes the span of the photon.

- The span of a photon is not determined by its frequency.

- 5.1

- The photon span is initially determined at its original emission per [], but is able to be changed subsequently. The reactive ends follow the surfaces of any wave guides that might be encountered, and the span may change as a result. This has no energy implications for the photon.

- 5.2

- In contrast to massy particles, e.g., electrons, the span is inversely related to the frequency and, hence, to the energy.

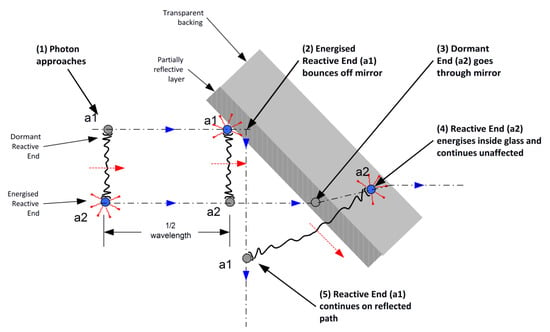

These principles are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A beam-splitter reflects only the energised reactive end. The dormant reactive end passes through. The diagram shows a p-polarised photon, but the principles generalise to other forms of polarisation. The key determinant of the path is the state (energised/dormant) of the pair of reactive ends at contact with the mirror.

The implication is that a reactive end reflects if it is in a suitably energised state at the point of contact. Otherwise it progresses deeper into the material, and may have a further opportunity to energise and be reflected. If it manages to pass entirely through the reflective layer without energising, then it has avoided reflection altogether. This outcome requires a reflective layer thin enough relative to the distance the RE can travel before re-energising, i.e., relative to the wavelength.

Hence, for a photon striking the partial mirror, there are three possible outcomes: both reactive ends reflect; neither reflect (both transmit through); or one reactive end reflects and the other transmits. The latter sends the reactive ends on non-parallel paths and changes the span of the photon.

These outcomes depend on the orientation (polarisation) of the particle, the precise phase location of the energised reactive end when it makes contact, and the frequency relative to the thickness of the mirror.

The lemmas also explain the observed variable output of the beam-splitter, whereby two beams generally emerge. This may be explained as the variable orientations (polarisations) of the input photons resulting in all three outcomes occurring. Furthermore, it is observed that if the polarisation of the input beam is changed then the beam splitter will favour one output. This, too, is consistent with the above Cordus explanation.

4.3.1. Explanation of MZ Interferometer in Default Mode

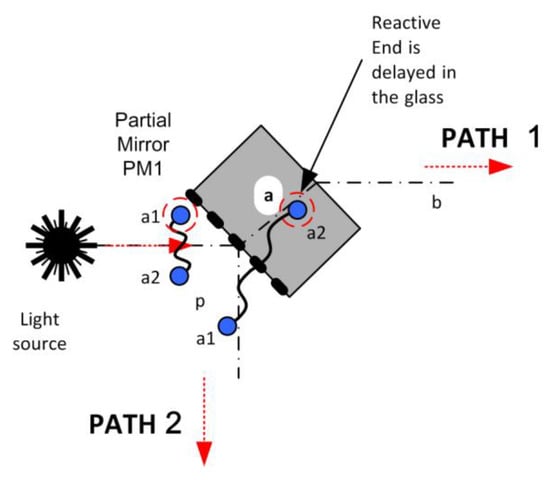

Having established the engagement mechanisms expressed in the lemmas, the explanation of the MZ device may now be continued. We consider a single photon, but the principles generalise to a beam of many. The photon reaches partial mirror PM1 (see Figure 4). The energised reactive ends reflect off the mirror, and the dormant REs transmit through. Depending on the polarisation and frequency states of the photons, some whole photons go down path 1, some down 2, and some are split to go down both.

Figure 4.

Photon particle interaction with the first partial mirror of the Mach–Zehnder interferometer.

The whole photons pose no particular problem, but a split photon needs explanation. Reactive end a1 reflects off the surface and continues on path 2 (pqrst). The dormant a2 reactive end passes through the mirror surface, re-energises beyond it (e.g., in the transparent backing material), and continues on path 1 (abcd). The order is unimportant; it is not necessary that the energised reactive end reaches the surface before the dormant reactive end. The reactive end that was energised at the mirror (a1 in this case) is always reflected (takes path 2). This is important in the following explanation. Assuming equal optical path length along 1 and 2, which is the case since the apparatus is tuned to achieve this, then both reactive ends come together again at partial mirror PM2, having undergone several frequency reversals.

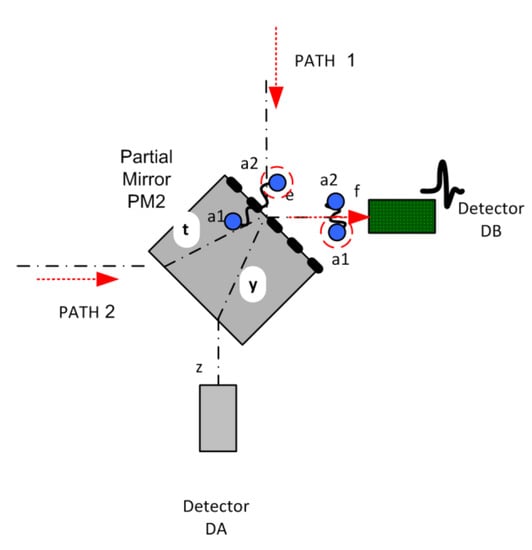

The explanation assumes that the path length is such that the reactive ends at PM2 are all in the opposite state to PM1, i.e., the path lengths are not only equal, but a whole even multiple of half-wavelengths. The particles that have travelled whole down path 1 or 2 now divert to detector DB. The explanation for the split particles follows: when reactive end a1 reaches the mirror surface of PM2 it is now in the dormant state, and therefore passes through to detector DB. By contrast, reactive end a2, which was dormant at PM1, is now energised at PM2, and reflects, taking it also to detector DB (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Photon behaviour at second partial mirror of the Mach–Zehnder interferometer.

Consequently, the photon always appears at detector DB, regardless of which path it took. The arrangement of the partial mirrors and the space between achieve this by the second mirror reversing the operation of the first. This operation occurs whether the reactive ends of a photon take the same path (whole photon) or different paths (split photon). The effect holds for a single photon and many individual photons; hence, the behaviour may be observed at macroscopic scales with beams or light.

The apparent intelligence in the system is not because the photons know which path to take, but rather because the MZ interferometer is a finely-tuned photon-sorting device that auto-corrects for randomness in the frequency phase.

The layout of an interferometer is usually taken for granted. However, such devices only work by design or tuning. The layout of the MZ or any other interferometer is decided beforehand and the apparatus is tuned by moving the components relative to each other until the expected functionality is obtained. Consequently, the layout is actually a set of additional covert variables which the observer (even if unknowingly) imposes on the experiment. This imposition enables and limits the ways the apparatus can behave. The partial mirrors provide the ability to send the reactive ends of a photon down different paths, but the ability to recombine them at one detector rather than the other is a consequence of how the interferometer is designed and the precision to which the path lengths are tuned. The detector at which the photon appears can be controlled by adjusting the path lengths.

4.3.2. MZ Interferometer in Open-Path Mode

Conventionally, the wave-particle dilemma occurs when one of the paths is blocked, since it suggests the weird solution that the photon “knew” which path was blocked without actually taking it. A mirror may be inserted at either D or S to deflect the beam away, but the photon nonetheless appears at detector DB (see Figure 6), despite the apparent mutual exclusivity of these two experiments.

Figure 6.

Inclusion of an extra mirror at D still results in photons arriving at detector DB.

From the Cordus theory the explanation is as follows: the layout of the interferometer ensures that those reactive ends that are not impeded will be forced by the partial mirrors to converge at DB. Regardless of which path, 1 or 2, is open-circuited, the remaining whole photons and the split photons (providing they are not absorbed first at g) will always appear at DB. Note that the theory provides that the whole energy of a photon collapses at the location where the first of its reactives is grounded []. The detectors are devices specifically designed to perform this collapse.

4.3.3. MZ Interferometer in Sample Mode

The MZ device may be used to measure the refractivity ks of a transparent sample placed in one of the legs, say S. The observed reality when using a beam of photons is that a proportion of the beam now appears at detector DA. The wave theory adequately explains this based on phase shift and constructive (destructive) interference, but cannot explain why the effect persists for single photons.

The Cordus explanation is that the sample introduces a small time delay to the (say) a1 reactive end of the split photon, so it arrives slightly late at partial mirror PM2. If sufficiently late, then a2 reaches the mirror in an energised state (it usually would be dormant at this point), and therefore reflects and passes to detector DA. If a2 is only partially energised when it reaches the mirror, then its destination is less certain; a single photon will go to one or the other detector depending on its precise state at the time. The proportioning is proposed to occur when a beam of photons is involved, as the random variabilities will place them each in slightly different states, and, hence, cause them to head to different detectors.

If path 1 or 2 in the MZ device is totally blocked by an opaque barrier (unlike the mirror mode), then the whole particles in that leg ground there, as do the split particles. However, the whole particles in the remaining leg continue to DB as before.

4.4. Explanation of Tunnelling

The partial mirror may be considered to operate on tunnelling effects, per lemma 3.3. The same principles also explain other tunnelling phenomena involving a barrier. The “barrier” could be a reflective surface, layers within prisms, or a non-conductive gap for electrons, e.g., Josephson junction.

The tunnelling effect is not explained by classical mechanics, but is by quantum mechanics. The typical QM explanation follows an energy line of thinking: the barrier requires a higher energy to overcome; the zero-dimensional particle is occasionally able to borrow energy from the external environment; it uses this to traverse the gap; the energy is then returned to the environment. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle provides the mechanism for the underlying indeterminism of energy. For QM, the randomness of tunnelling arises due to not all particles being able to borrow the necessary energy.

In contrast, the proposed Cordus mechanism shows that the reactive end of a particle does not react to the barrier when in the dormant state. If the dormant reactive end can completely traverse the barrier before re-energising, then it passes through the barrier. The other reactive end may likewise have an opportunity to do so; hence, the whole particle may jump the barrier. The thickness of the barrier is a known detriment to tunnelling, and this is consistent with the Cordus explanation.

The Cordus concept of the fibril providing instantaneous co-ordination between reactive ends is also consistent with the observation that some tunnelling effects can be superluminal and non-local []. For the Cordus theory, the randomness of tunnelling arises due to the variability of the particle’s orientation and phase when it meets the barrier and is not primarily an energy borrowing phenomenon. We thus make the falsifiable prediction that with suitable control of frequency, orientation, and phase, it should be possible to get all incident particles to cross the barrier.

5. Discussion

We have shown that it is possible to give an explanation for the path dilemmas in the MZ interferometer, in its various modes, for single photons and beams. The results show that it is possible to conceive of explanations based on physical realism. This does not require virtual particles, parallel worlds, pilot waves, or intelligent photons. Nonetheless, what it does require is physical structures at the sub-particle level, i.e., a non-local, hidden-variable solution. Importantly, while the solution requires some premises, these are not unreasonable and are not precluded by empiricism or other physics. Dirac was of the view that photons only interfered within themselves, not with other photons []. The present theory is consistent therewith. It proposes a type of dipole structure for the photon, with co-ordination occurring between the two ends, and the ability of the two ends to take different optical paths. The theory is also accepting of quantum field theory with its oscillators and fields, but diverges by proposing a specific internal structure to the particle and a physical mechanism for the tunnelling effect. Hence, while the NLHV perspective might seem foreign and incompatible from a quantum theory perspective, it appears there may be significant areas of agreement.

The contribution of the work is, therefore, its explanation of interferometer and tunnelling behaviour in terms of physical realism and NLHV theory.

5.1. Implications

The work demonstrates a new way to conceptualise fundamental physics other than via the stochastic properties of 0-D points. Allowing particles to have internal structure yields explanations of interferometer behaviour and tunnelling. The wider implication is that the stochastic nature of quantum mechanics is interpreted as a simplification of a deeper NLHV mechanics. The Cordus theory, therefore, provides a means to conceptually reconnect the mathematics of quantum theory to physical realism. Given that the Cordus theory spans diverse areas of physics (optics, particles, cosmology), which other theories struggle to achieve, this work suggests that the NLHV sector is not as barren as it seems.

5.2. Limitations

The major limitation of the theory is that its explanations are conceptual and it does not yet have a mathematical formalism to represent the particle concept. This makes it difficult to represent the concepts, e.g., its explanations for the MZ interferometer behaviour, to the same level of quantitative detail that is available to quantum mechanics.

5.3. Future Research Opportunities

There is an opportunity for future research to develop a mathematical representation of the particle behaviour. This is a call for a novel mathematical approach, since there are multiple physical structures at the sub-particle level that need to be represented. There are also several empirical research opportunities. One could be to test the tunnelling mechanism proposed here for the partial mirror (see also the falsifiable prediction above). Another could be to devise other ways of disrupting the MZ interferometer to test the proposal that the reactive ends of the photon occasionally go down different legs, i.e., the photon span is stretched to macroscopic dimensions. The Cordus theory is a proto-physics or candidate theory of new physics, and consequently there are also many possibilities for future research of a conceptual nature.

6. Conclusions

One of the central quantum dilemmas of the wave-particle duality is the ambiguity of where the photon is going and which path it will take. Existing approaches either reconfigure the photon as a wave or treat the problem as simply probabilistic. The present work suggests that the locus of the photon is determined by the orientation and frequency state of its reactive ends when they meet a partial mirror. Furthermore, it is proposed that each of the two reactive ends of the Cordus particle may take a different locus. Hence, the theory is able to explain the behaviour of the Mach–Zehnder interferometer in its three modes: default-, open path-, and sampling-mode.

The Cordus theory provides a conceptual framework for how physical theory may be extended to levels more fundamental than currently reached by wave theory or quantum theory. This has the potential to provide a new understanding of photon behaviour in unusual situations. In summary, the present results show that the Mach–Zehnder interferometer is an unexpectedly finely-tuned passive photon-sorting device that auto-corrects for randomness in the frequency phase. It behaves somewhat like a macroscopic optical meta-material.

Author Contributions

The authors of [] contributed to the development of the idea for the Cordus particle and the explanation for wave particle duality []. D.J.P. developed the explanations for the photon path dilemmas for the current paper. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no financial conflict of interest regarding this work. The research was conducted without personal financial benefit from a third party funding body, nor did any such body influence the execution of the work.

References

- Pons, D.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.M.; Pons, A.J. Wave-particle duality: A conceptual solution from the cordus conjecture. Phys. Essays 2012, 25, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, C.G. What is a Photon? Foundations of Quantum Field Theory. 2018. Available online: https://www.physics.usu.edu/torre/QFT/Lectures/QFT_text.pdf. (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Dirac, P. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, D.J. A physical basis for entanglement in a non-local hidden variable theory. J. Mod. Phys. 2017, 8, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, H. The Theory of the Universal Wave Function: The Many-Worlds interpretation of Quantum Mechanics; DeWitt, B.S., Graham, N., Eds.; Princeton Series in Physics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- De Broglie, L. Recherches sur la théorie des quanta (Researches on the quantum theory). Ann. Phys. 1925, 3, 3–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D.; Bub, J. A proposed solution of measurement problem in quantum mechanics by a hidden variable theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1966, 38, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, T.D.; Wigner, E.P. Localized states for elementary systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1949, 21, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, A.S. On the localizability of quantum mechanical systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1962, 34, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, I.; Saigo, H. Photon localization revisited. Mathematics 2015, 3, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J. How does a particle detect the gradient of a field? viXra. 2020. Available online: http://viXra.org/abs/2009.0004 (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Pons, D.J. Inner process of Photon emission and absorption. Appl. Phys. Res. 2015, 7, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.J. Energy conversion mechanics for photon emission per non-local hidden-variable theory. J. Mod. Phys. 2016, 7, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.J. Pair production explained in a hidden variable theory. J. Nucl. Part. Phys. 2015, 5, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.J. Annihilation mechanisms. Appl. Phys. Res. 2014, 6, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pons, D.J.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.J. Asymmetrical genesis by remanufacture of antielectrons. J. Mod. Phys. 2014, 5, 1980–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.J. Speed of light as an emergent property of the fabric. Appl. Phys. Res. 2016, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J. Internal Structure of the Photon (Image Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0). Wikimedia Commons. 2015 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License). Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Internal_structure_of_the_photon.jpg (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Howell, J.C. Beam Splitter Input-Output Relations; Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nimtz, G. Tunneling confronts special relativity. Found. Phys. 2011, 41, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, D.J.; Pons, A.D.; Pons, A.M.; Pons, A.J. Quo Vadis, Photon? (Cordus Conjecture Part 1.2). viXra 2011, 1–22. Available online: http://vixra.org/abs/1104.0017 (accessed on 2 September 2020).

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).