1. Introduction

Interest in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has been growing in recent years because of their mission flexibility owing to the continuous advancement of engineering-related fields, including flight control, automatic systems, and the aerospace industry [

1]. This makes UAVs an appealing research object for both civilian and military applications.

Achieving today’s demanding performance, environmental requirements, and economics [

2,

3], new combustion technologies are being developed by aeroengine manufacturers to improve aircraft fuel efficiency and lower pollutant emissions. On the other hand, much attention is given to reducing the weight and to increasing the energy density of the batteries for the electric propulsion system to increase flight endurance [

4,

5], which still remains a challenge. Hybrid-electric propulsion system (HEPS) seems to be the most practical option [

6] for energy-efficient, cleaner [

7], and quieter aeronautical propulsion systems, given its ability to integrate the benefits of both the conventional propulsion system and the electric system [

8]. Despite this, many objectives need to be met for the technology to be viable [

9] and widely used.

Numerous models and configurations of hybrid propulsion UAVs [

10] have been developed and studied to date. Jo and Kwon [

11] investigated the development process of a hybrid UAV for VTOL, which could be operated manually from the ground or totally autonomously. They reported satisfactory results for the flight mission time, hovering tolerance, and pitching angle. Maxim et al. [

12] have suggested a new sizing methodology for UAV development. They studied a hybrid UAV with five fixed rotors, one rotor for horizontal thrust, and four rotors for a vertical lift. Later, a quad tilt wing VTOL UAV was studied by Muraoka et al. [

13]. It consists of tandem tilt wings with propellers span-wise placed in the middle of each wing, showing great potential for hybrid UAVs. These UAVs exhibited better lift characteristics in the front and rear wings. Lucena et al. [

14] proposed a double hybrid tail sitter configuration for multi-rotor UAVs using a cutting-edge approach. They showed, via several flight tests executing vertical takeoff and landing, that their model was able to enhance flight endurance. In a simulation conducted by Flores et al. [

15], they described the control design and hardware execution of a tilt-rotor aircraft. The UAV was designed to obtain high speed during the cruise with better-hovering capability. De Vries et al. [

16] suggested a method to calculate the aero-propulsive interaction effects for leading-edge-mounted distributed propulsion (DP). Their results showed that DP greatly increases wing loading and improves the cruise lift-to-drag ratio by 6%, albeit the growth in the aircraft weight results in a 3% increase in energy consumption.

Controlling UAVs is extremely important to successfully apply UAVs in the real world. Wada et al. [

17] investigated the pitch control of a fixed-wing UAV using a reinforcement learning approach by examining the impact of time delays on flight controller performance and estimating the effective delay. Cowling et al. [

18] simulated and enhanced the trajectory planner of a UAV quadrotor. They demonstrated that the quadrotor UAV can track the reference trajectory reasonably well despite significant perturbations. By employing an algorithm to control the quadrotor’s sensitivity component and reaction speed, Minh and Ha [

19] built a control system in which the flight mission can successfully monitor a certain fixed object in space. Zhang and Cong [

20] developed a novel model of the UAV’s motor and propeller. They claimed that their model was able to perform better than the nonlinear model in terms of reaction time and real-time. Xie et al. [

21,

22] created a basic model of a HEPS UAV. They concluded that using a HEP system on a UAV leads to 7% fuel savings. Cardone et al. [

23] developed a simplified model that allows for defining the hybrid system architecture during the early design phases; they also reported that the margin of error between the simulation and the experimental results was less than 5%. Albuquerque et al. [

24] have detailed a mission-based aircraft preliminary design optimization technique for the evaluation of adaptive technologies. They showed that the mission profile had a significant impact on the choice of any adaptive technology combination, and the weight of the adaptive mechanisms significantly influenced the overall performance. In turn, Zhou and Zhang [

25] introduced a novel control parameter approach using an evolutionary algorithm-based optimization for an aerial manipulator based on a multi-objective optimization where they identified the most suitable control settings to satisfy competing goals, such as decreasing the integrated time error and the control rate.

In conceptual and preliminary aircraft design phases, mission performance drives design options and vehicle sizing [

26,

27]. At these early stages of the design, either very simple or very complex flight performance methods are often used. The former methods usually use quasi-static conditions to estimate mission performance needs (fuel and battery consumption, flight times, etc.) for the different segments [

28,

29]. Step changes between consecutive mission segments are common for simplicity. The latter methods are considerably more complex as they use flight simulation resorting to detailed aircraft dynamic models [

30,

31]. These models imply considerable knowledge of the vehicle’s aerodynamic, propulsion, inertial, and control characteristics, which are not always available at the early design stages. While the simple models lack the capability to account for the transient effects that occur between consecutive segments, the complex models require dynamics and control modeling, which often require extensive resources to obtain and are not always practical to develop at the beginning of the design.

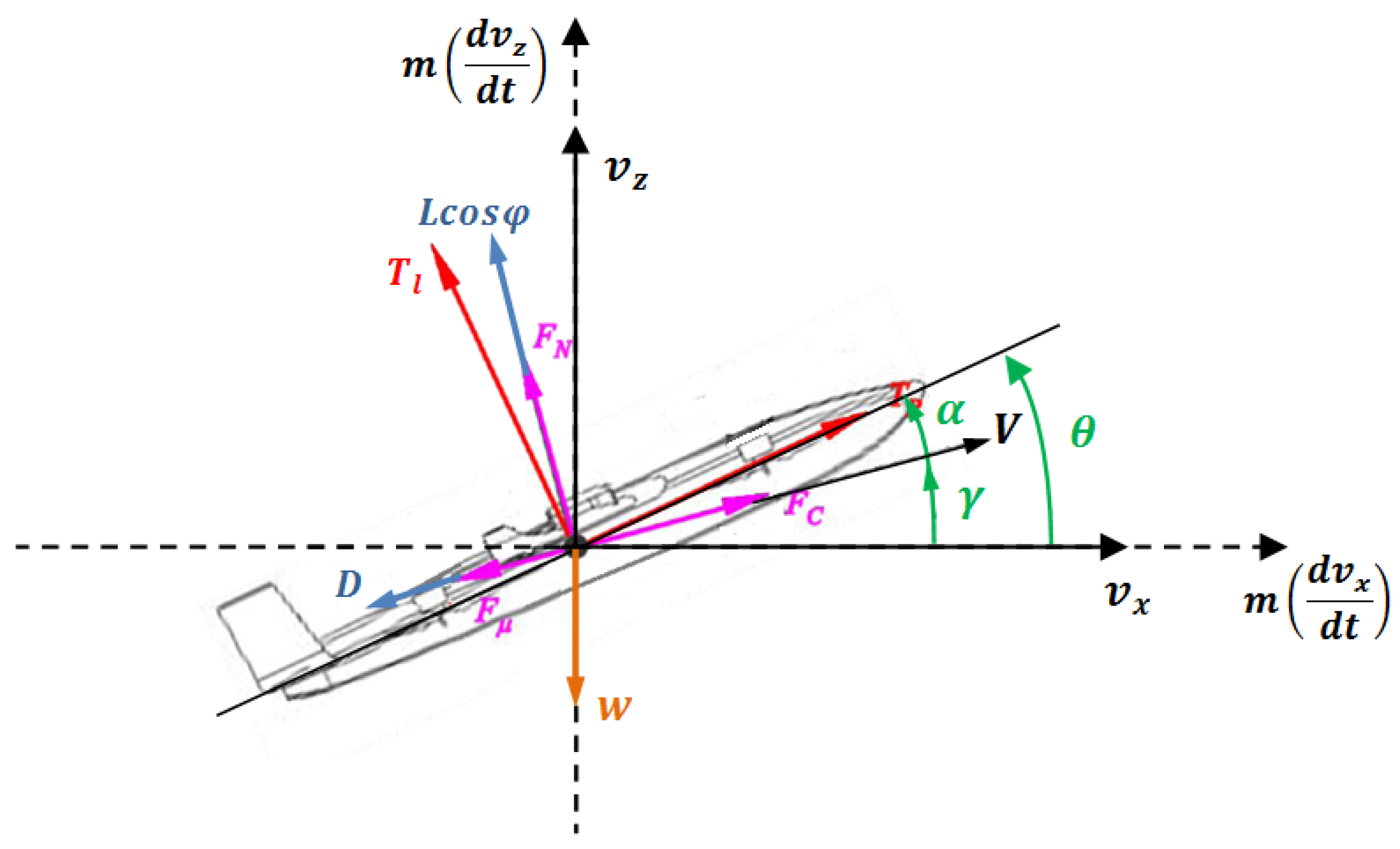

This work presents an intermediate method that uses the two-dimensional (2D) equations of motion integrated over time to take into account transient effects between consecutive mission segments, yet not considering elaborate aerodynamic models which require a large number of aircraft aerodynamic derivatives and inertia parameters. This might be important for predicting fuel and battery consumption and flight times in short-duration missions having vertical and conventional flight modes.

Thus, a simple 2D flight model was developed that allows us to estimate the flight performance and analyze the mission of a fixed-wing and multi-rotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) with a hybrid electric propulsion system (HEPS) with both conventional and VTOL capabilities in order to analyze the effect of control parameters on the UAV’s transient response during a given flight simulated mission. The control is based on the continuous specification of pitch angle, propulsion thrust, and lift thrust to achieve the conditions of a given flight segment. Six different mission profiles were considered to perform a parametric study to help select an appropriate combination of the control parameters and achieve better control performance. This parametric study is applied in a systematic way.

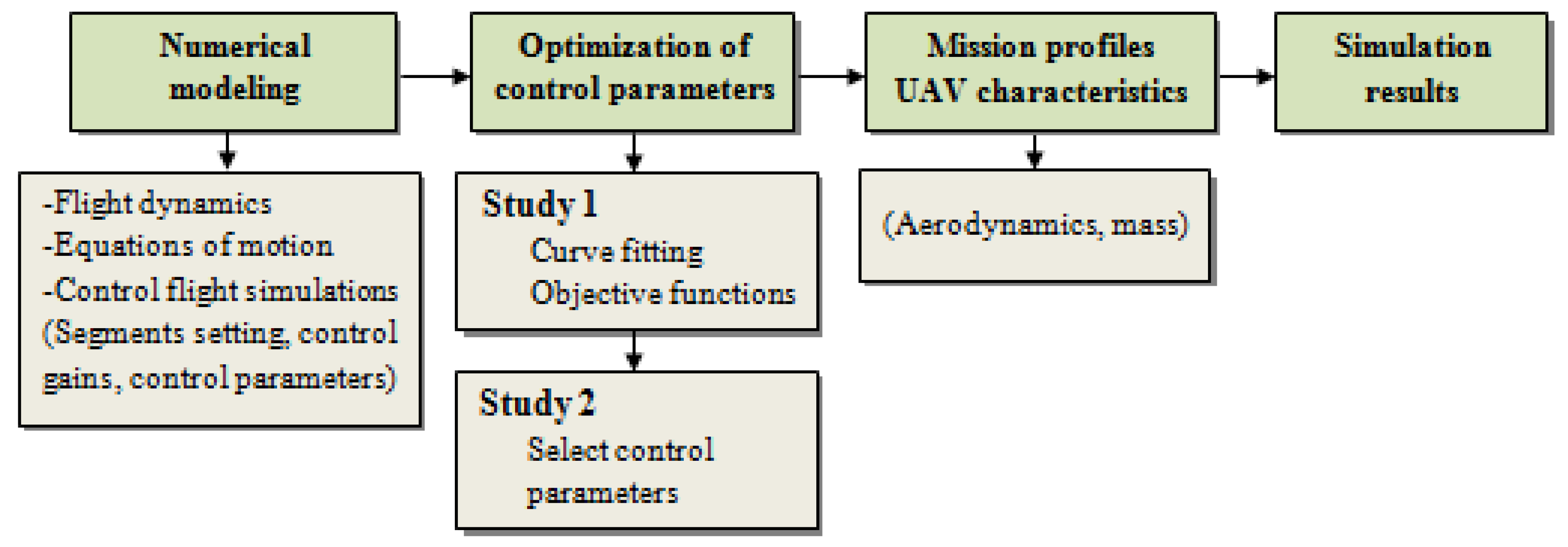

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows (

Figure 1):

Section 2 describes the numerical formulation encompassing the equations of motion, the control approach for various flight conditions, and the calculation of control gains from given control parameters.

Section 3 details the procedure to identify the lower and upper bounds of the control parameters used in the parametric study aimed at selecting the control parameters’ combination for best performance.

Section 4 presents the hybrid propulsion VTOL UAV characteristics and the different analyzed mission profiles. The results obtained from the simulations performed in the parametric study are discussed in

Section 5.

Section 6 contains the conclusions.

3. Optimization of Control Parameters

Two objectives are considered in the current study. One is to identify the control parameters and corresponding lower and upper bounds such that a given mission is well simulated without control divergence. The other is to analyze their effects on the UAV flight simulation by performing both conventional and VTOL segments in different mission profiles in order to obtain the best combination of control parameters that minimize a given mission performance function.

In the first objective, the mission segments that exhibit transient oscillatory responses are analyzed. As the optimal solution cannot be found from an arbitrary initial choice, one way to accurately determine the period of oscillation and the damping ratio of the motion is to find the best-fit curve through the simulation data points. To this end, the least-squares polynomial-curve fit is used for the pitch attitude and thrust responses. Hence, all peaks and valleys of the oscillatory response are detected automatically and used to obtain the maximum and minimum bound curves of the motion; then, a sinusoidal-fit curve equation is used to fit the data points and to obtain the amplitude, the damping, the frequency, and the phase angle, as follows:

where

,

,

, and

represent the amplitude, the damping ratio, the natural frequency, and the phase angle, respectively.

This procedure is applied to the cruise segments, which exhibit the transient oscillatory response at the end of the transition to gain speed or at the end of a climb. After extracting the values of

,

,

, and

, we need to define the lower and upper bounds of the control parameters. This is performed by separately analyzing the thrust and the pitch angle (

θ) curves of each of the specified mission profiles. The function in this problem, Equation (38), is calculated for every

ith case in a set of

n control parameter combinations:

where

,

, and

are weighting coefficients;

and

represent the amplitude and the average amplitude, respectively;

and

are the damping ratio and the average damping ratio, respectively;

and

are the natural frequency and the average natural frequency, respectively. The value of

must be maximized to reduce the oscillations and smooth out the control response. From all analyzed mission profiles, the minimum and maximum values of the control parameters that maximize Equation (38) are selected as lower and upper bounds for the next analysis.

The second objective is to optimize the control parameters by selecting the best combination that minimizes the following equation:

where

,

,

, and

denote weighting coefficients;

and

are the time and the maximum time at the end of the mission, respectively;

and

are the hover

x-position difference and the maximum hover

x-position difference, respectively;

and

are the remaining fuel mass and the maximum remaining fuel mass at the end of the mission, respectively;

and

are the remaining battery energy and the maximum remaining battery energy at the end of the mission, respectively.

Equation (39) is calculated for every ith specified combination of the control parameters. The minimization of aims to achieve better control performance by selecting an appropriate combination of the control parameters weighing the resulting mission time, x distance difference, and fuel mass and battery energy consumption. This approach results in selecting the control parameter combination that leads to a mission that takes less time to complete and uses less energy.

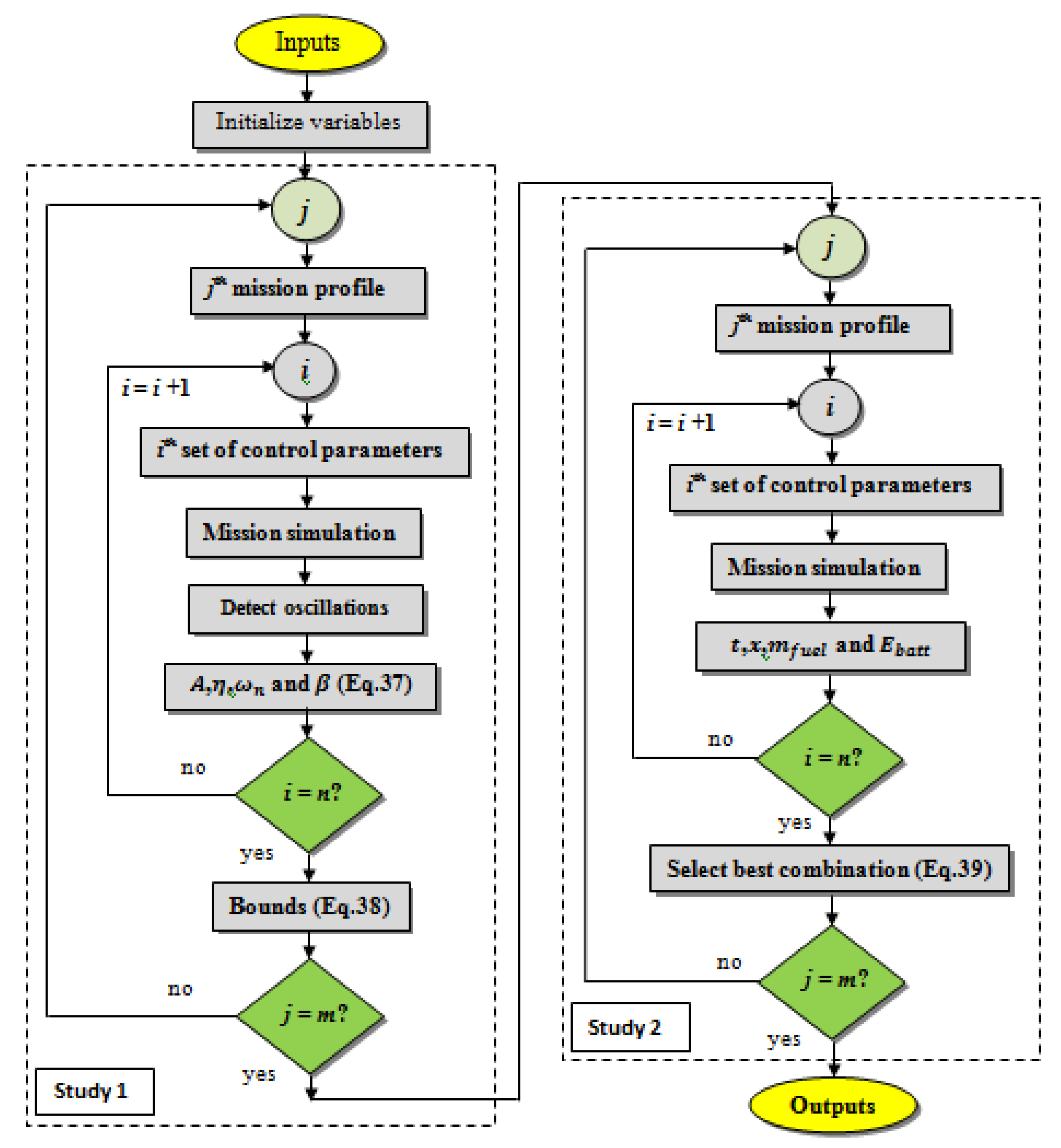

The procedure to estimate the best control parameters is presented in the flow chart shown in

Figure 3. In the first study, the curve fitting procedure is applied to define the minimum and maximum bound curves, using Equation (37) to fit the flight simulation data points and to obtain the amplitude, damping, frequency, and phase angle of the transient motion. Then, a set of minimum, maximum, and step-change values for every control parameter is applied in a set of

n combinations. After running the possible combinations affecting the cruise, the control parameters’ values that minimize Equation (38) are selected as bounds for the second study. Then, in the second study, the control parameters are optimized by minimizing Equation (39) to achieve better control performance.

4. Mission Profiles and UAV Characteristics

In this study, six different UAV sample mission profiles are analyzed. The selected different profiles capture the different flight capabilities typical of a fixed-wing multi-rotor VTOL aircraft. The first mission profile (Mission 1) consists of nine flight phases, starting with a vertical takeoff at 3 m/s up to 45 m altitude, an acceleration transition up to 20 m/s, a cruise of 200 m at 23 m/s, a deceleration transition to 0 m/s, a hover of 60 s at 45 m altitude, a second acceleration transition, a cruise of 200 m at 23 m/s and another deceleration to 0 m/s, and finally a vertical landing to 0 m altitude at −1.5 m/s.

In the second mission profile (Mission 2), five flight phases are chosen: a vertical takeoff at 3 m/s up to 45 m altitude, an acceleration transition up to 20 m/s, a cruise of 2000 m at 23 m/s, and a deceleration transition to 0 m/s before a vertical landing to 0 m altitude at −1.5 m/s.

Eleven flight phases are used in the third mission profile (Mission 3): a vertical takeoff at 3 m/s up to 45 m altitude, an acceleration transition up to 23 m/s, a climb at 23 m/s till 100 m altitude before a cruise of 200 m at 100 m altitude at the same speed, a deceleration transition, a hover of 60 s at 100 m altitude, a second acceleration transition, a cruise of 200 m distance at 23 m/s and 100 m altitude, a descent at 28 m/s to achieve 45 m altitude and another deceleration to 0 m/s, and at the end a vertical landing to 0 m altitude at −1.5 m/s.

For the fourth mission profile (Mission 4), seven phases are studied: a vertical takeoff at 3 m/s up to 45 m altitude, an acceleration transition up to 23 m/s, a climb of 100 m at 23 m/s till 100 m altitude before a cruise of 2000 m at 100 m altitude at the same speed, a descent at 28 m/s and 45 m altitude, a deceleration transition, and a vertical landing to 0 m altitude at −1.5 m/s.

Mission profile five (Mission 5) consists of a takeoff, a climb of 100 m at 23 m/s, a cruise of 200 m at 23 m/s, a transition, a hover of 60 s at 100 m altitude, a transition and a second cruise of 200 m distance and 100 m altitude at 23 m/s, and a final descent at 28 m/s to the takeoff altitude with the goal of landing.

The last mission profile (Mission 6) has five flight phases: a takeoff at 23 m/s, a climb of 100 m at 23 m/s, and a cruise of 2000 m at 23 m/s, ending by descent at 28 m/s to the takeoff altitude with the goal of landing.

The studied hybrid propulsion VTOL UAV is typical of a light UAV under 25 kg of the maximum takeoff mass. It has one internal combustion engine for horizontal thrust and eight electric motors arranged in pairs in a quadcopter configuration for the vertical lift. The UAV’s main characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The model combines numerous system components: an internal combustion engine (ICE) coupled with a generator and propeller for horizontal propulsion, whereas vertical propulsion comprises a battery, electric motors (EM), an electric speed controller (ESC), and propellers. The aerodynamic and propulsion characteristics of the UAV were estimated using the methodology presented by Albuquerque et al. [

24] and are summarized below in Equations (40)–(42).

The lift and drag coefficients,

and

, respectively, can be defined by the following equations:

Given the UAV characteristics and mission data, the propulsion system curves of the internal combustion engine and propeller used to estimate the forward flight thrust are:

where

is the maximum airspeed of the propeller,

is the internal combustion engine power setting,

is the maximum engine speed,

N is the current engine speed,

,

ρ is the air density,

is the ISA sea-level air density, and

is the number of engines.

The propulsion system curves of the electric motors and propellers used to estimate the vertical flight thrust are defined as follows:

where

is the electrical motors power setting,

I is the motor’s drawn current, and

is the number of electric motors.

5. Results and Discussion

A parametric study is carried out to analyze the effects of the control parameters on the UAV flight simulation using conventional and VTOL flight segments in different mission profiles.

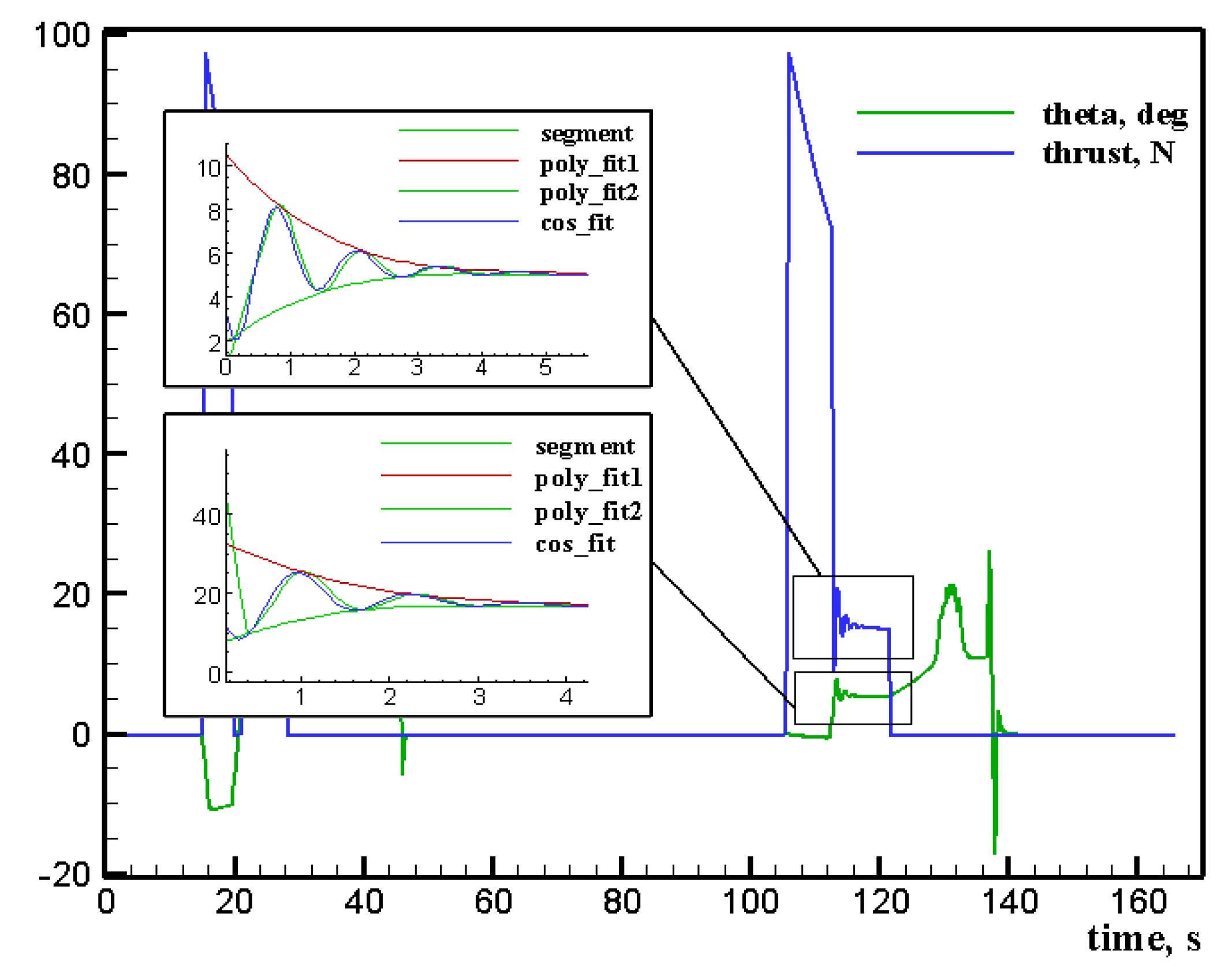

Figure 4 shows the polynomial-curve fit results of the pitch angle (

θ) and the propulsion thrust responses for the cruise ofMission1. From these, all the peaks and valleys are detected automatically and used in the curve fitting procedure to define the maximum and minimum bound curves using Equation (37) to fit the flight simulation data points to obtain the amplitude, damping, frequency, and phase angle. A set of minimum, maximum, and step-change values for every control parameter was defined, and after running the possible combinations affecting the cruise, the control parameters’ values that minimize Equation (38) were selected as bounds and are shown in

Table 2.

Then, a second parametric study is carried out to optimize the control parameters by minimizing Equation (39) to achieve better control performance by selecting an appropriate combination of the control parameters, taking into account the time,

x-distance difference, fuel mass, and battery energy consumption. The optimized parameters are shown in

Table 3 for each mission with the average values (AVR) and the standard deviation (STDEV).

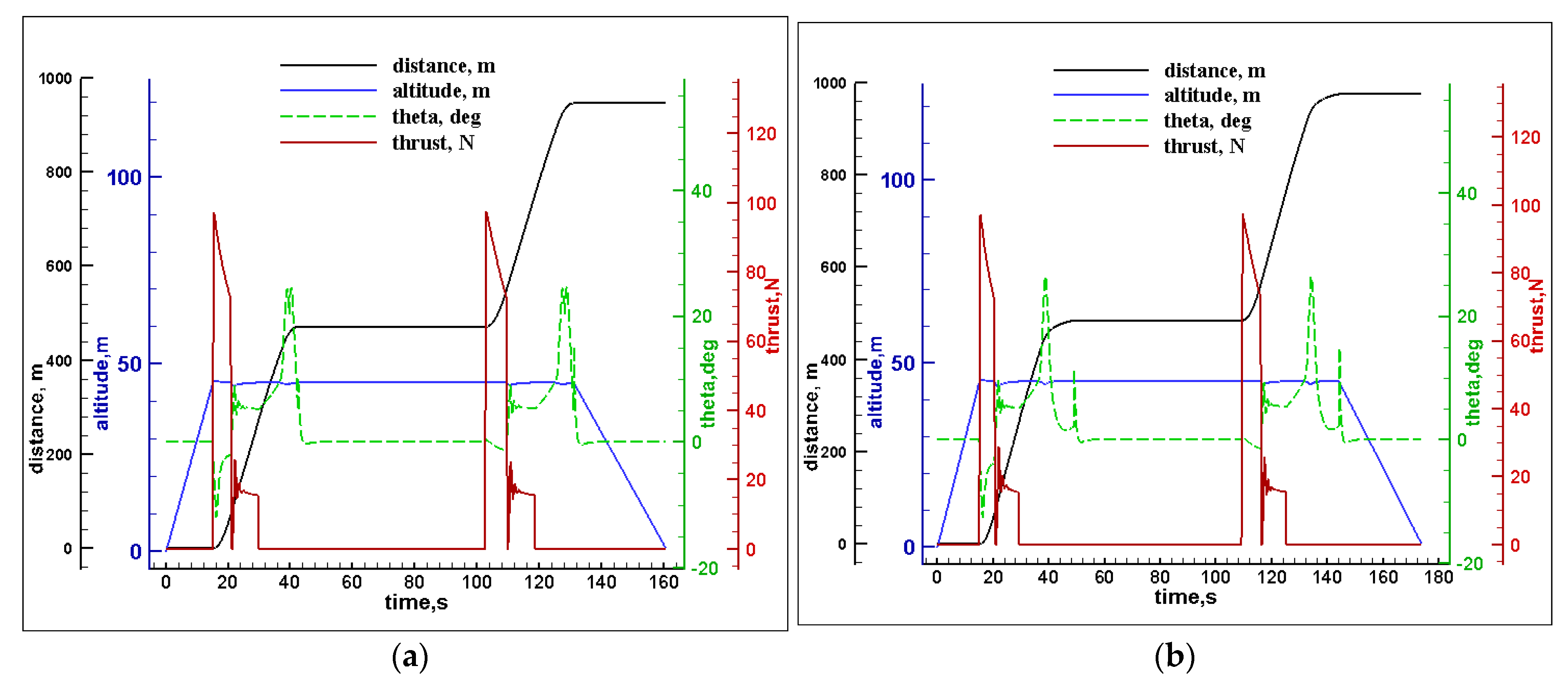

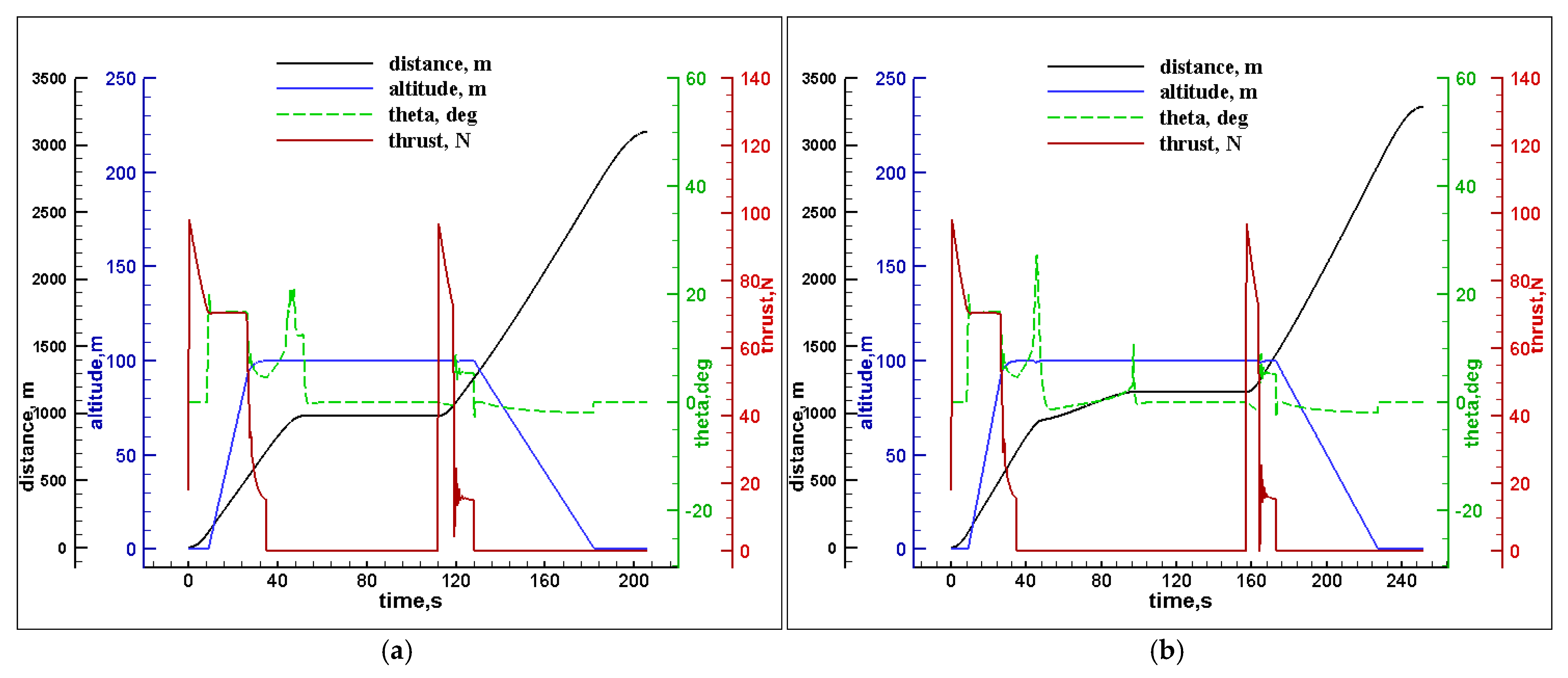

In

Figure 5a, during the vertical takeoff from

t = 0 s to 15 s, the UAV climbs vertically until 45 m of altitude is reached under the electric rotors thrust where the pitch angle is kept at 0°, then it starts to move forward for the acceleration transition with the engine thrust while being assisted by the electric motors until the speed of 20 m/s is achieved, with a pitch angle of −10°. After

t = 20.7 s, the electric motors are turned off, and the UAV starts cruising for 200 m at 23 m/s using the engine thrust, where lift force is obtained from the wings. At

t = 29.8 s, the UAV switches to the electric motors and turns off the engine; the pitch angle increases up to 25°, creating an increased drag force for the deceleration transition until the speed reaches 0 m/s. Then, it hovers for 60 s, and the pitch angle becomes 0° again. At

t = 102 s, the UAV starts the engine for the acceleration transition while the rotational speed of the motor decreases until the speed reaches 20 m/s, then the electric motors are turned off for the cruise at 23 m/s for 200 m using only the engine thrust, where lift force is obtained entirely from the wings; another deceleration transition starts at

t = 118 s, where the engine is turned off, and the electric motors are turned on; the pitch angle rises to increase the drag force until the speed becomes 0 m/s, and the UAV starts the vertical landing at

t = 131.1 s using electric motors, and the pitch angle becomes 0° again. From

Figure 5b, we can see that between

t = 29.2 s and

t = 48 s, the UAV took 7 s longer to start the hover than in

Figure 5a. This is also noticed during the second transition from

t = 125 s to 144 s.

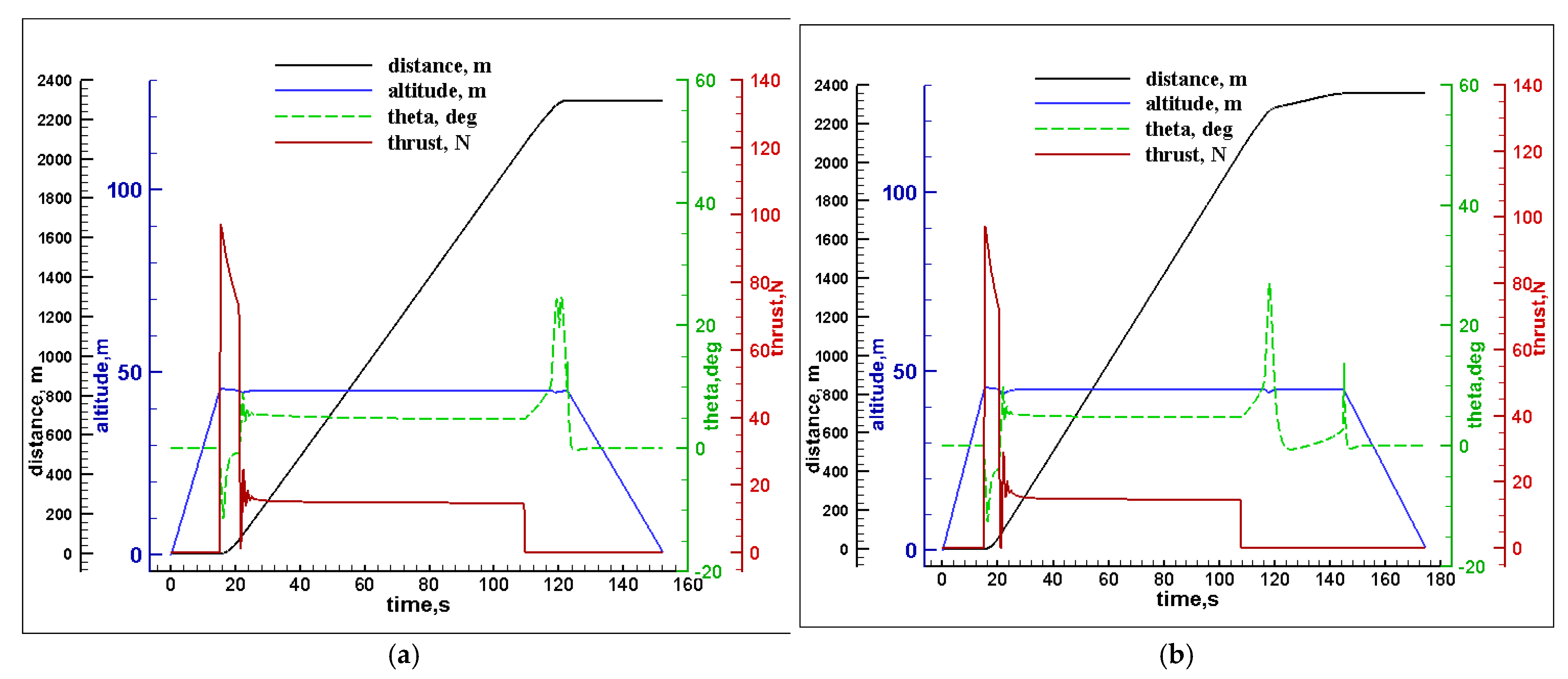

In

Figure 6a, the UAV climbs vertically and reaches 45 m of altitude under the electric motors, where the pitch angle is kept at 0° for 15 s; then it starts to move forward for the acceleration transition with the engine thrust while being assisted by the electric motors until the speed of 20 m/s is achieved, in which the pitch angle becomes −10° due to the propulsion engine. After 21.2 s, the electric motors are turned off, and the UAV starts cruising using the engine thrust, and the lift force is obtained from the wings for 2000 m at 23 m/s. At

t = 109.3 s, the UAV switches to the electric motors and turns off the engine, and the pitch angle increases to 25°, leading to an increased drag force for the deceleration transition until the speed reaches 0 m/s. At

t = 122.6 s, the pitch angle becomes 0° again, and the UAV starts the vertical landing.

Figure 6b shows the mission profile with the average parameters in which the UAV spends almost three times longer than when using the optimized parameters to switch from the cruise to the vertical landing between 107.7 s and 144.7 s.

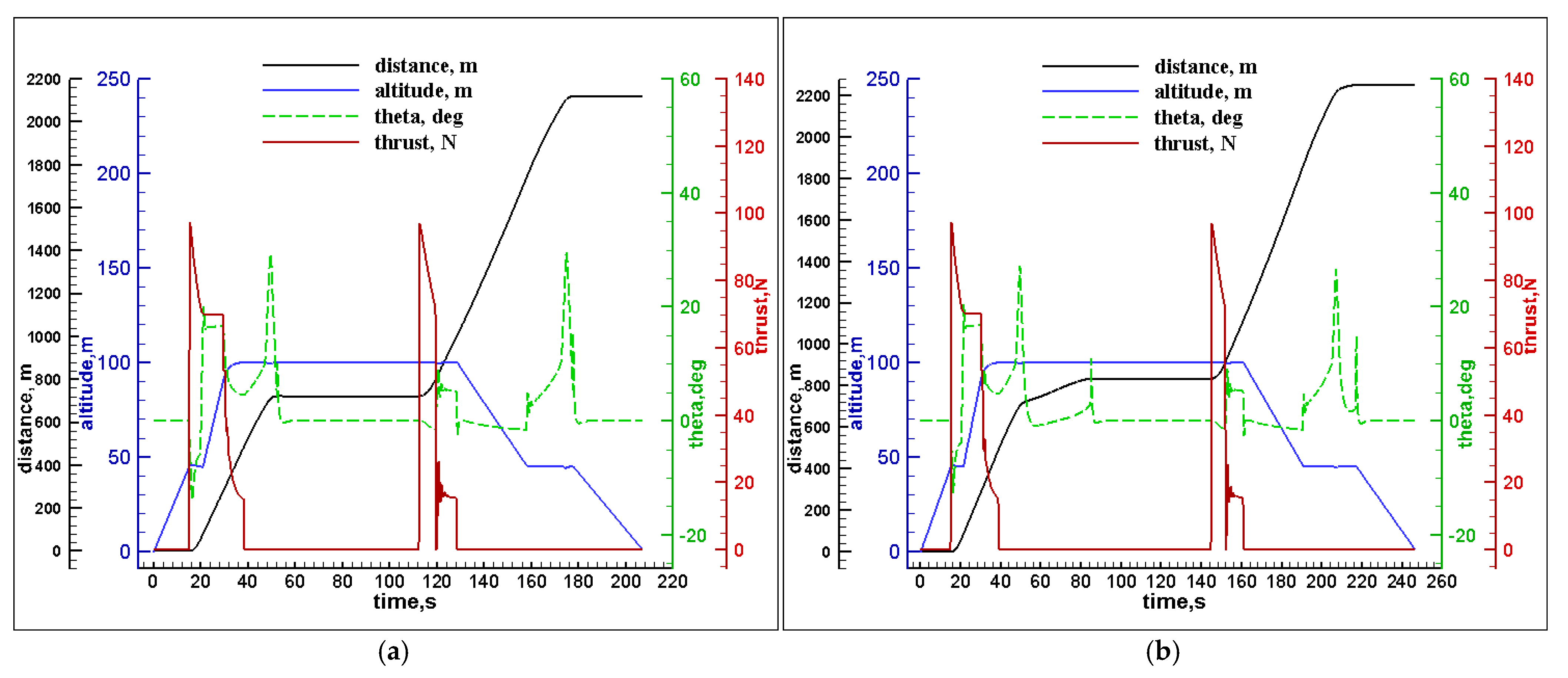

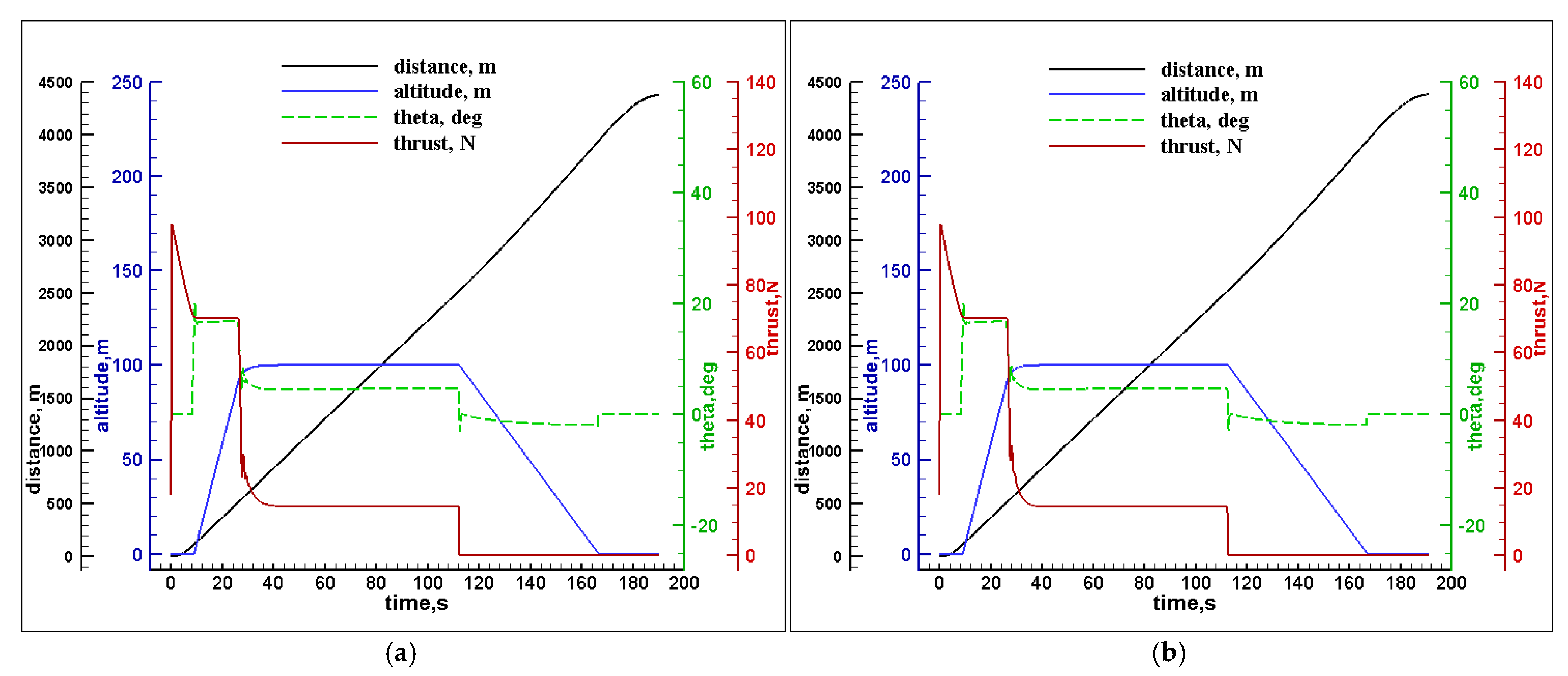

In

Figure 7a, from

t = 0 s to

t = 15 s, the UAV starts the vertical takeoff to reach 45 m of altitude using the electric motors and a pitch angle of 0°; then the engine thrust is turned on to get the horizontal speed while the rotational speed of the electric motor decreases. At

t = 19.9 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, the UAV starts to climb as a conventional fixed-wing aircraft to reach 100 m altitude, and the electric motors are turned off. At

t = 29.7 s, the UAV starts cruising for 200 m using the engine thrust, where the lift force is obtained from the wings. From

t = 38.3 s to 52.2 s, the engine is turned off, and the electric motors are turned on for the deceleration transition, making the pitch angle become 25°, causing an increased drag force until the speed achieves 0 m/s to hover for 60 s using the electric motors. At

t = 112.4 s, the UAV switches to an acceleration transition, where the engine is turned on while the rotational speed of the electric motor decreases; at

t = 119.4 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, and the UAV starts cruising for 200 m using only the engine thrust while the electric motors are turned off, where lift force is obtained entirely from the wings. At

t = 128.4 s, the UAV starts descending to reach 45 m of altitude until

t = 158 s, where the UAV switches to the electric motors and turns off the engine, and the pitch angle is increased, leading to an increase in drag force for the deceleration transition until the speed reaches 0 m/s. Here, the pitch angle becomes 0° again, and the UAV starts the vertical landing using the electric motors. The effect of the average parameters can be seen in

Figure 7b, in which delays of 32 s and 8 s are observed relative to the optimized parameters’ case during the deceleration transitions, the first between

t = 38.7 s and

t = 85 s and the second between

t = 19.3 s and 217 s, respectively.

Figure 8a shows the results of Mission 4, where the UAV starts with a vertical takeoff to 45 m of altitude using the electric motors and a pitch angle of 0° until

t = 15 s; then the engine thrust is turned on to get the horizontal speed, while the rotational speed of the electric motors decreases for the acceleration transition. At

t = 20.8 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, and the UAV climbs until an altitude of 100 m is reached as a conventional fixed-wing aircraft with the electric motors turned off. At

t = 30.5 s, the UAV starts cruising for 2000 m using the engine thrust, where the lift force is obtained from the wings. At

t = 116.9 s, the UAV starts descending to reach an altitude of 45 m until

t = 146.5 s, where the UAV switches to the electric motors and turns off the engine. In the process, the pitch angle increases, leading to a greater drag force for the deceleration transition until the speed reaches 0 m/s. At

t = 166.8 s, the pitch angle becomes 0° again, and the UAV lands vertically using the electric motors. In

Figure 8b, we can also notice that the UAV takes 27 s longer in the deceleration transition from

t = 146 s when compared to

Figure 8b.

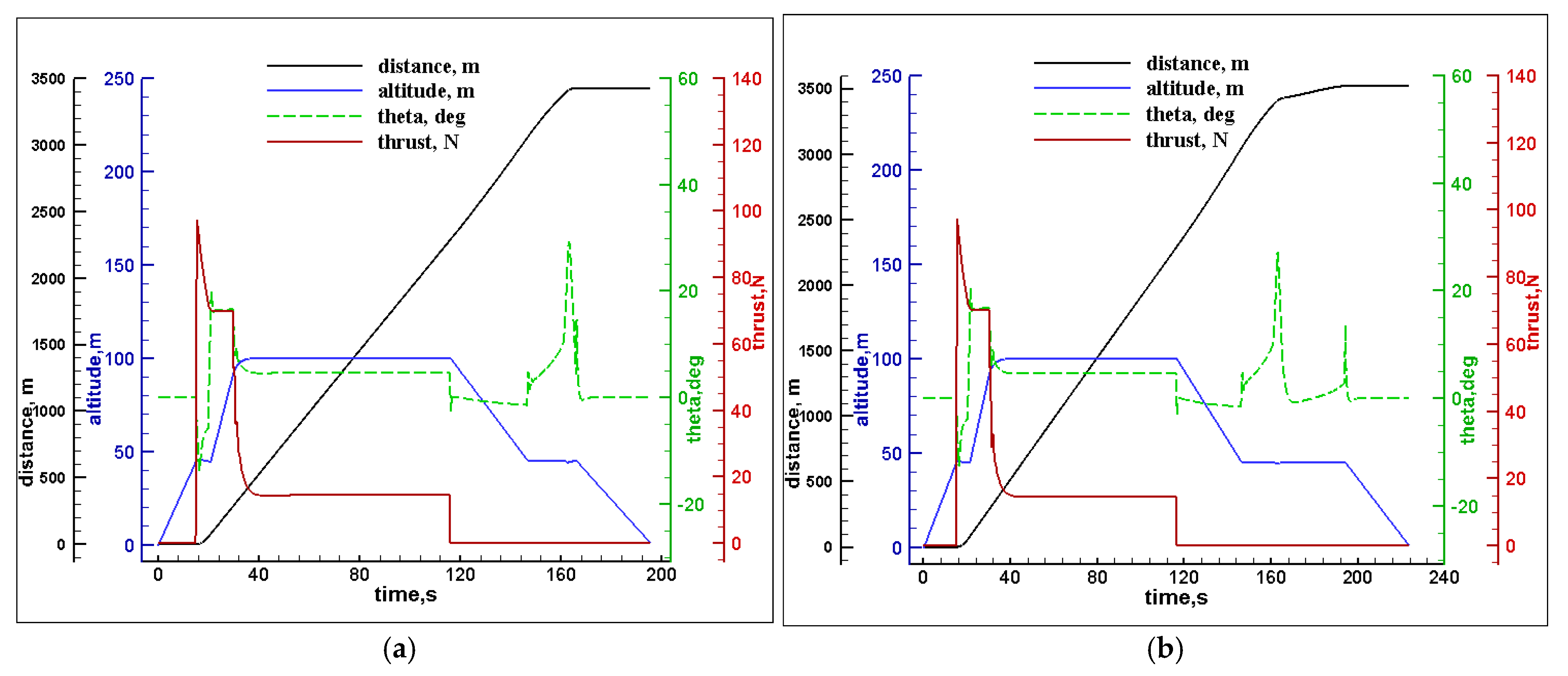

Figure 9a presents the results of Mission 5. The UAV starts with a conventional takeoff using the engine; at

t = 8.3 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, and the UAV climbs as a conventional fixed-wing aircraft up to an altitude of 100 m. After

t = 26 s, the UAV starts cruising for 200 m. From

t = 34.9 s to 51.6 s, the engine is turned off, and the electric motors are turned on in the deceleration the transition, where the pitch angle increases, causing an increased drag force until the speed achieves 0 m/s to hover for 60 s using the electric motors. At

t = 111.8 s, the UAV switches to the acceleration transition, in which the engine is turned on, while the rotational speed of the electric motors decreases; at

t = 118.9 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, and the UAV starts cruising for 200 m using only the engine thrust, while the electric motors are turned off until

t = 129.7 s when the UAV starts descending to the final landing. Looking at

Figure 9b, from

t = 34.8 s, the UAV takes 70 s in the deceleration transition before starting hovering, which is 45 s longer than when using the optimized parameters (

Figure 9a).

Figure 10a shows the results of Mission 6. The UAV starts with a conventional takeoff using the engine, and at

t = 8.3 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s when the UAV climbs as a conventional fixed-wing aircraft up to an altitude of 100 m. After

t = 26 s, the UAV starts cruising for 2000 m. From

t = 34.9 s to 51.6 s, the engine is turned off, and the electric motors are turned on in the deceleration transition, where the pitch angle is increased, causing the drag force to increase until the speed achieves 0 m/s to hover for 60 s using the electric motors. From

t = 111.8 s, the UAV switches to an acceleration transition, in which the engine is turned on while the rotational speed of the electric motors decreases; at

t = 118.8 s, the horizontal speed reaches 23 m/s, and the UAV starts cruising for 2000 m using only the engine thrust, while the electric motors are turned off. When

t = 127.9 s, the UAV starts descending until the final landing. Compared with

Figure 10b, no differences can be seen in this mission profile since there was no transition segment.

From the comparison of the results between the mission simulations using the optimized and the average control parameters, we can notice that the control parameters affect the mission in each deceleration transition, resulting in a longer time to reduce the cruise speed to stand still. This segment is characterized by a large increase in pitch angle to increase the drag to help reduce the speed in a short time. It is observed that if the control parameters in this segment are not well-tuned, the controller struggles to adjust the pitch angle.

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 present a summary of the comparison of the optimized parameters and the average parameters of each simulated mission, where Δ

t, Δ

x,

, and

represent the time, traveled distance, fuel mass and battery energy, respectively, spent in each segment. Battery energy consumption is at its highest during hover and vertical flights, while fuel consumption is highest during the cruise and descent. In each mission, the control parameters show greater influence during deceleration transitions, as compared with the optimized parameters, where the average control parameters lead to longer time intervals and larger energy and fuel consumption.

The analysis of Mission 1 was repeated using a quasi-static analysis, whereby at each time instant during the simulation, the appropriate speeds are set, and from the equilibrium of horizontal and vertical forces, the propulsion thrust, the lift thrust, and the pitch angle are computed. In this case, there is no direct control of the flight, but the state of the aircraft is prescribed at each time instant. This is a more typical approach to estimating mission performance in the early stages of aircraft design due to its simplicity.

Table 10 presents a summary of the comparison of the mission profile analyzed with the approach presented above and with the quasi-static approach. It is observed that the quasi-static approach underestimates both fuel and battery energy consumption and overestimates flight time and distance covered. These differences occur because, unlike in the controlled simulation, in the quasi-static analysis, there is a step change in the aircraft state when it transitions from one segment to the next; therefore, the transient response is not captured. It is also observed that greater differences take place in the transition segments where great changes in speed and pitch attitude occur. The transient response at the beginning, at the end, and when propulsion modes change between lift thrust and propulsion thrust or vice-versa is thus important in predicting these segments’ performance.