1. Introduction

Automated visual inspection is a critical factor in the safety of operations [

1]. In the industrial field, particularly in high-stakes aerospace, metallurgy, and manufacturing sectors, where cracking, denting, and corrosion are among the major surface-level causes of significant maintenance time loss and other structural failures [

2]. Timely detection and correction can ensure that defects are identified and, when properly addressed, reduce downtime, securing airworthiness [

3]. Manual inspection protocols, despite their usefulness, are highly reliant on human labour and can readily give way to subjective judgments, uneven results, and lower rates of inspection [

4]. As a result, deep learning-based systems, especially CNNs, have become the standard for automated visual inspection [

1].

CNNs are superior to conventional feature engineering models since they have the potential to learn layered features of raw image data [

5]. They are, however, known to decline considerably in cross-domain deployments [

6]. The common variations in surface texture, lighting, curvature, and defect morphology cause domain shift and result in CNNs misclassify novel visual patterns because of a shift in the distribution of learned features [

7]. This difficulty is even more acute in industrial cases when the labelled data of the target domain are either limited or absent due to factors such as proprietary issues, annotation time or cost, or low defect prevalence [

8].

Despite the impressive advances in deep learning-based defect detectors, certain challenges are yet to be addressed during implementation in real-world settings. The majority of the literature is focused on lightweight architectures, which do not explicitly implement mechanisms to prevent domain shift or employ more advanced domain-adaptation algorithms, which are too expensive to run in real-time or on edge devices, thereby restricting their relevance to real-world applications in both real-time and edge-based inspection systems. Though the attention-based models enhance defect-relevant region localization, they tend to overfit to domain-specific visual features. Regularization, e.g., DropBlock, is often intended to perform single-domain robustness and is not optimized to be cross-domain transferable. As a result, the deployed methods often cannot be generalized to visually dissimilar inspection settings, especially in instances of limited annotated target-domain data. Specifically, the existing techniques have three main weaknesses: (i) lightweight convolutional neural networks do not have explicit mechanisms to mitigate domain shift between visually dissimilar inspection conditions. (ii) Attention-based models excel at defect localization but tend to overfit to domain-specific visual features and (iii) existent regularization techniques are not domain-aware, and are instead optimized for single-domain robustness. This work fills these gaps and combines the refinement of features guided by attention and progressive and transfer-aware spatial regularization within a lightweight backbone of MobileNetV2.

We aim to combine the superior hierarchical feature learning ability of neural network architectures along with attention mechanisms [

9] that have recently emerged in the AI landscape. We achieve this by suggesting a new classification framework which is based on the MobileNetV2 backbone, further enhanced with two synergistic components:

The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM): This module sequentially applies spatial and channel-wise attention, directing the model’s focus toward defect-relevant regions such as micro-cracks or corrosion streaks [

10].

The Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock): a novel regularization module that generates attention-guided spatial masks encouraging the learning of semantically diverse and domain-transferable features by selectively suppressing overactive regions during training [

11].

Novelty and Key Contributions

Novel architectural fusion: first integration of CBAM with a progressive, transfer-aware dropout mechanism (TDropBlock) for enhanced attention and regularization under domain-shifted conditions.

Two-phase training protocol: combines source-domain pretraining with target-domain fine-tuning using minimal supervision.

Comprehensive evaluation: validated under zero-shot and fine-tuned settings, with ablation studies, PCA visualizations, and confusion-matrix analyses.

Deployable design: achieves high accuracy while remaining lightweight and edge-compatible, suitable for real-time industrial inspection systems.

The rest of this paper has the following structure.

Section 2 includes the overview of available literature on defect detection, attention-based models, and cross-domain learning.

Section 3 also presents the framework that is proposed where the network architecture and the training strategy are outlined.

Section 4 gives the experimental set-up and quantitative performance analysis with

Section 5 giving qualitative analysis to further analyze the results, ablation analysis, discussion, and conclusion.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Framework

In order to deal with the problem of cross-domain defect classification in industrial settings, we introduce a lightweight and generalizable deep-learning framework that makes use of MobileNetV2 and is enhanced with two synergistic modules namely, Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock). The framework is specifically designed to avoid performance drops due to domain shifts, particularly in cases where the target domain has limited labelled data.

CBAM selectively concentrates attention on the channel and spatial domains of a network, focusing on defect-salient regions to enhance the ability of the network to detect subtle patterns like micro-cracks or diffuse corrosion.

Our regularization approach, TDropBlock, builds on the traditional spatial dropout methodology and gradually introduces an attention-directed suppression on a network at progressively deeper levels of the network. In particular, it takes inverted attention masks based on intermediate feature activations and masks out the most salient parts, causing the model to explore redundant spatial paths. This masking, which is class-sensitive and dynamic encourages diversity of features and eliminates overfitting to domain-specific cues, which is crucial in improving generalisation.

The framework in

Figure 1 demonstrates source-domain pretraining followed by target-domain fine-tuning for cross-domain defect classification. The training process is built into two consecutive stages to resemble a realistic deployment scenario:

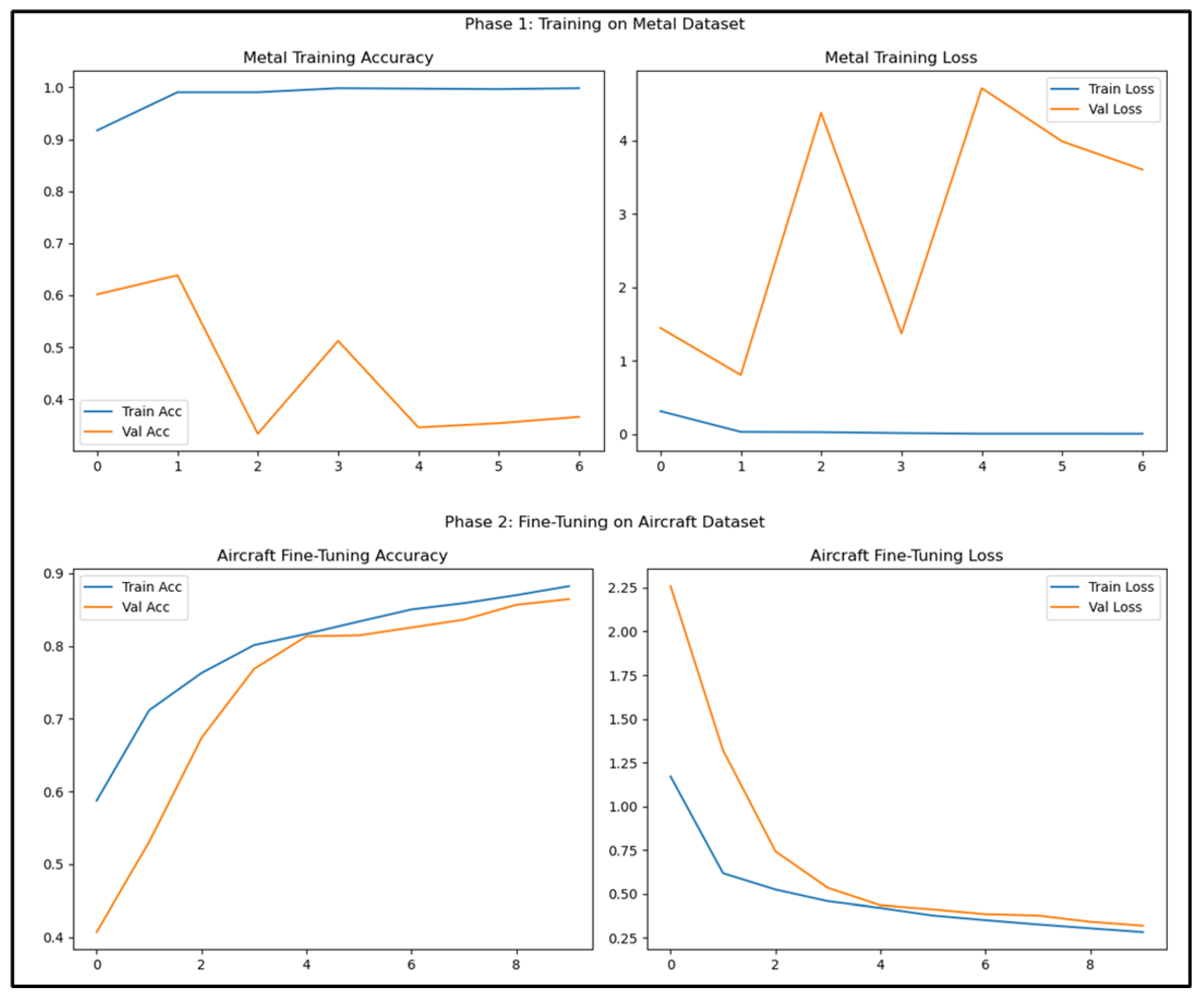

Phase 1—Pretraining: Initially the model is trained on a labeled and balanced metal surface dataset comprising visually homogeneous defects.

Phase 2—Fine-tuning: The pretrained model is adapted to a visually dissimilar aircraft defect dataset using transfer learning under low-supervision settings.

The framework demonstrates source-domain pretraining followed by target-domain fine-tuning for cross-domain defect classification. This two-phase training pipeline not only enables the model to learn generalizable defect representations from a well-labeled source but also encourages robust adaptation to new domains with minimal data and annotation effort. The proposed framework is first trained on the metal surface dataset to learn generic defect-related features and is subsequently fine-tuned on the aircraft surface dataset. This training strategy enables effective knowledge transfer from a controlled industrial domain to a more complex and unconstrained real-world domain.

3.2. Architecture Design

3.2.1. Backbone: MobileNetV2

To achieve a balance between representational capacity and computational efficiency, an essential requirement in industrial inspection and edge-deployment situations, MobileNetV2 was chosen as the backbone architecture [

30]. MobileNetV2 also uses depth-wise separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks to significantly reduce the computational cost compared with heavier convolutional networks, while preserving the ability to learn discriminative feature representations [

31]. This efficiency is particularly relevant in the context of cross-domain defect classification, as the proposed framework incorporates additional modules for attention and transfer-aware regularization. A lightweight backbone ensures that the overall model complexity remains manageable and that deployment feasible in resource-constrained industrial environments, such as embedded inspection systems or on-site monitoring platforms [

31]. Moreover, MobileNetV2 has demonstrated consistent performance across a range of visual inspection tasks, making it a practical and reliable choice for studying the effects of attention mechanisms and progressive regularization under domain-shifted conditions [

31]. Based on these observations, MobileNetV2 is adopted as the backbone and modified by eliminating the initial classification head to enable integration of the suggested attention (CBAM) and regularisation (TDropBlock) modules.

3.2.2. Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

To enhance the localization of defect-relevant regions, CBAM is inserted after the final convolutional block of MobileNetV2. This module sequentially applies:

Channel Attention: Emphasizes salient features by processing global average and max-pooled vectors through a shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP).

Spatial Attention: Applies a 2D convolution over pooled channel features to highlight informative spatial regions.

This dual attention mechanism strengthens the network’s capability to extract fine-grained, domain-relevant defect features, improving robustness in both the source and target domains.

3.2.3. Regularization Module: Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock)

In our proposed system, a novel regularization mechanism termed Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock) has been introduced, which is designed to improve generalization across domain boundaries. Progressive TDropBlock differs from existing adaptive dropout methods such as AutoDropout and group-wise dynamic dropout in both its objectives and design. While prior methods adapt dropout rates or channel groups within a single domain, primarily to reduce overfitting, Progressive TDropBlock is explicitly formulated for cross-domain transfer learning. It employs spatially structured block-wise dropout with a progressively increasing drop probabilities during fine-tuning, allowing the model to gradually suppress source-domain-specific spatial patterns while promoting domain-invariant representations. This transfer-stage-aware regularization strategy enables more stable and robust adaptation across domains, which is not addressed by existing adaptive dropout approaches.

Further, unlike conventional dropout, which deactivates neurons uniformly at random, TDropBlock generates inverted attention masks through lightweight depth-wise convolutions. These saliency-guided masks are applied in a depth-aware fashion, which gradually increases dropout strength in deeper layers. This approach not only simulates an occlusion of dominant activations, but also encourages the network to explore alternative discriminative pathways, ultimately reducing overfitting and introducing class-sensitive spatial regularization. The model enables learning redundant but transferable features that are vital for domain adaptation. It does this by progressively masking high-activation regions. Despite this added complexity, TDropBlock introduces negligible computational overhead, making it suitable for real-time industrial deployment. TDropBlock extends standard DropBlock by progressively increasing the regularization effect during training. The key idea is to suppress high activation spatial blocks in the feature map using an inverted attention mask. This mask is computed from CBAM’s attention maps, so low attention regions are retained while high attention areas are suppressed.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the key steps of the proposed Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock) regularization strategy.

| Algorithm 1 Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock) |

Require: Feature map F, CBAM attention map A, epoch e

Ensure: Regularized feature map - 1:

Compute block size - 2:

Compute drop probability - 3:

Invert CBAM attention to obtain suppression mask M - 4:

Randomly drop proportion of regions guided by M - 5:

Apply mask: - 6:

return

|

The block size

b and drop probability

p increase linearly with the training epoch

e:

This encourages the network to explore alternate discriminative regions and avoid overfitting to high saliency zones in the source domain. The linear growth strategy was selected for its simplicity, stability, and predictable regularization behavior during fine-tuning, allowing gradual adaptation without introducing abrupt changes that could destabilize training. While more complex schedules are possible, empirical validation showed that linear progression provides a reliable balance between performance and training stability.

In Equation (

1), the initial block size

and drop probability

control the strength of regularization at the beginning of fine-tuning, ensuring stable knowledge transfer from the source domain without excessive feature suppression. The growth rates

and

determine how rapidly spatial occlusion and stochastic feature dropping is intensified across training epochs. As training progresses, the gradual increase in both block size and drop probability enforces stronger regularization, discouraging over-reliance on source-domain–specific high-saliency regions and encouraging the learning of more robust and domain-invariant representations under domain shift. The hyperparameters

,

,

, and

were selected via a grid search on the validation set, where candidate values were evaluated to balance regularization strength and classification performance.

3.3. Dataset Description

To evaluate the cross-domain generalization capability of the proposed framework, experiments were conducted using two visually and contextually diverse datasets: a metal surface defect dataset as the source domain and an aircraft surface defect dataset as the target domain.

Source Domain–Metal Surface Dataset: The metal surface dataset consists of a total of 1104 images spanning three defect categories, namely crazing (276 images), pitted (552 images), and rolled (276 images). The images are acquired under controlled industrial inspection settings, with relatively uniform illumination, planar surfaces, and minimal background clutter. Due to its structured appearance and limited intra-class variability, this dataset serves as a suitable source domain for initial feature learning and pretraining.

Target Domain–Aircraft Surface Dataset: The aircraft surface dataset contains 11,121 images annotated into three defect classes: crack, dent, and rust, which are semantically aligned with the defect taxonomy of the metal dataset. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets. The training set consists of 2314 crack images, 2648 dent images, and 2822 rust images. The validation set contains 496 crack, 567 dent, and 605 rust images, while the test set includes 496 crack, 568 dent, and 605 rust images. Compared to the source domain, this dataset exhibits significantly higher intra-class variability due to complex surface curvature, reflections, diverse lighting conditions, and irregular defect morphology. These characteristics closely resemble real-world aircraft maintenance and inspection scenarios.

Dataset splits are predefined using approximately an 80% train, 10% test, 10% val stratified split across training, validation and testing sets to ensure consistent evaluation across experiments, and class-wise distributions are explicitly reported to maintain transparency and reproducibility.

Figure 2 presents representative crack, dent, and rust defects from the aircraft surface dataset.

Figure 3 illustrates sample crazing, pitted, and rolled defects from the metal surface dataset.

3.4. Data Augmentation and Qualitative Analysis Tools

To ensure input consistency and enhance the model generalization, images are resized to a fixed dimension of 224 × 224 × 3 and normalized to the [0, 1] range. During training, real-time data augmentation is applied to introduce variation and reduce overfitting.

The augmentation strategies include:

Random horizontal flipping.

Random rotation within .

Zoom augmentation up to 20%.

Width and height shift up to ±10%.

The augmentations assist in modelling actual real-life changes in imaging conditions, including camera angle, distance, and illumination. Synthetic class balancing is not used because the datasets are originally balanced. All changes are done through the tf. image API of TensorFlow in the data pipeline to make the pipeline efficient and reproducible.

Along with quantitative performance measures, the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used as a qualitative measure to investigate the structure of the learned feature space. PCA allows conducting a visual evaluation of feature separability and alignment between the source and target domains before and after transfer learning by projecting high-dimensional features into a lower-dimensional representation. In order to enhance the interpretability of the proposed model and to examine its decision-making behavior, the Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) is employed to come up with visual explanations of the networks predictions. Grad-CAM identifies the areas in the input images that are class-discriminative and therefore, we can look at whether or not the model is concentrating on the areas of defects or whether it is strained by spurious backgrounds.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Configuration

Entire experimentation and evaluation were done in TensorFlow 2.13 and executed on machine equipped with an NVIDIA RTX GPU (16 GB VRAM). Both metal and aircraft datasets were preprocessed identically, resized to 224 × 224 × 3 pixels, and split using an 80:10:10 ratio for training, validation, and testing.

Training Parameters:

Batch Size: 32

Loss Function: Categorical Cross-Entropy

Input Shape: 224 × 224 × 3

Classifier Head: Global Average Pooling followed by a Dense Softmax layer (3-class output)

Training Callbacks:

EarlyStopping with patience of 5 epochs

ReduceLROnPlateau (factor= 0.5, patience = 3)

ModelCheckpoint for saving the best performing model based on validation loss

To ensure reproducibility and transparency, all code, preprocessed datasets, and trained model checkpoints have been archived and are intended for public release upon publication.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

A wide range of assessment metrics are used to thoroughly evaluate both in-domain classification performance and cross-domain generalization. These are captured separately for both zero-shot evaluation and post-transfer fine-tuning, showing various aspects of predictive reliability.

Primary Metrics:

Accuracy: Represents the proportion of total correct predictions. While commonly reported, it may obscure model weaknesses on minority classes. It is defined as:

where

denotes the number of true positives for class

i,

C is the number of classes (here

), and

N is the total number of samples.

F1-Score: Represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, making it effective for evaluating performance on hard-to-separate or ambiguous defect categories:

where

Macro F1-Score:Computes the F1-score independently for each class and then averages them, treating all classes equally and highlighting performance on underrepresented categories:

Cohen’s Kappa (

): Measures inter-class agreement corrected for chance, providing an additional view of prediction reliability under domain shift:

where

is the observed agreement and

is the expected agreement by chance, computed from the class-wise marginal probabilities.

These metrics provide a multi-faceted evaluation of both the model’s classification accuracy and its robustness to domain variability, which are essential in real-world deployment scenarios such as aircraft maintenance or industrial quality control

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative comparison between zero-shot evaluation and transfer learning performance across standard classification metrics.

4.3. Zero-Shot Evaluation: Evidence of Domain Shift

To simulate real world deployment conditions without prior exposure to the target domain, a zero-shot evaluation performed wherein the model trained exclusively on the metal defect dataset was directly tested on aircraft defect images without any fine-tuning. As expected, performance deteriorated significantly due to domain shift:

Accuracy decreased to 35.40%

Macro F1-Score fell to 0.20

Cohen’s Kappa approached 0.02, indicating near random agreement

Interpretation: This class-wise analysis conducted shows a strong prediction bias toward the dent class, while crack and rust defects were either misclassified or completely overlooked, suggesting that the features learned during pretraining failed to generalize to the target domain. Such a collapse shows the non-transferability of representations across domains with distinct visual characteristics. Variations in surface texture, defect morphology, and lighting conditions between the metal and aircraft datasets likely disrupted internal feature alignment, thereby exacerbating the domain induced degradation.

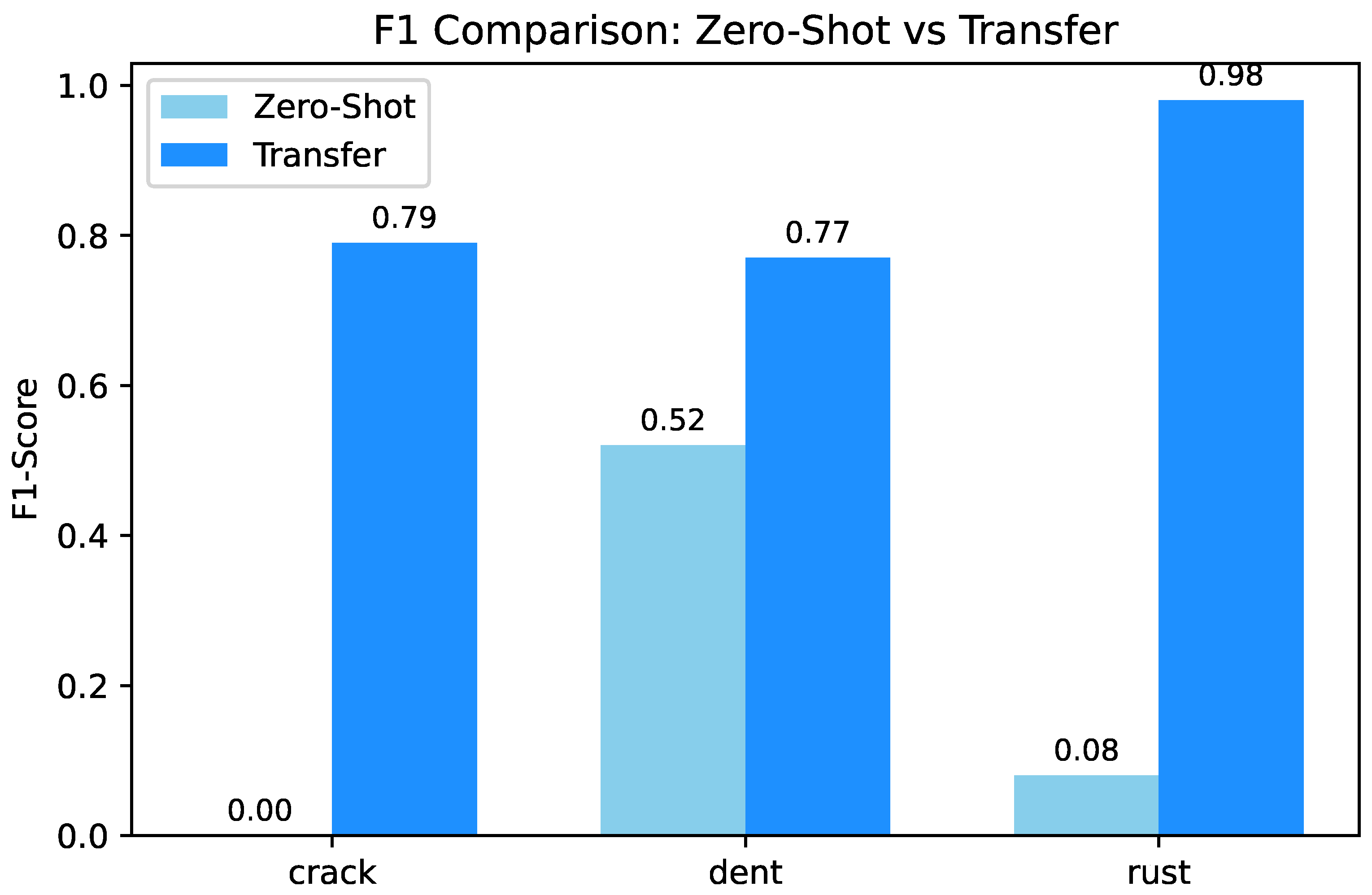

The bar plot in

Figure 4 illustrates the stark contrast between zero shot and transfer learning performance. While the pretrained model performs poorly on unseen aircraft data (Accuracy: 35.00%, Macro F1: 0.20, Cohen’s Kappa: 0.02), fine-tuning on the target domain significantly boosts all metrics, achieving 86.45% accuracy, 0.85 macro F1-score, and 0.78 Cohen’s Kappa highlighting the critical role of domain adaptation.

4.4. Transfer Learning Results

Following the application of transfer learning on the aircraft defect dataset, the model demonstrates a prominent performance boost, confirming the efficacy of domain adaptation. Fine-tuning the pretrained weights with a limited set of labeled aircraft images led to marked improvements across all key evaluation metrics.

Overall Performance:

These results reflect a high degree of prediction consistency and strong generalization to the target domain especially notable when compared with the sharp performance degradation observed in the zero-shot setting.

Combined with the substantial improvement in Macro F1-score, this evidence indicates that the model effectively recalibrates its internal representations through low-shot adaptation, aligning them with the semantic structure of the target domain.

The learning curves in

Figure 5 illustrate a progressive decline in validation loss accompanied by a steady increase in accuracy during the fine tuning phase. This trend confirms the stability of the optimization process and the effective convergence of the model under transfer learning.

To better understand the model’s behavior across individual defect categories,

Table 3 presents the per class precision, recall, and F1-scores.

Table 4 summarizes the overall performance metrics, reinforcing the effectiveness of the proposed framework following transfer learning.

4.5. Confusion Matrix and Visualizations

To better understand the model’s class wise performance and its ability to differentiate features under domain shift, we employ both confusion matrix analysis to visualize classification reliability and feature separability.

Following the application of transfer learning, the class-wise F1-score comparison shown in

Figure 6 highlights the differential improvement across defect categories.

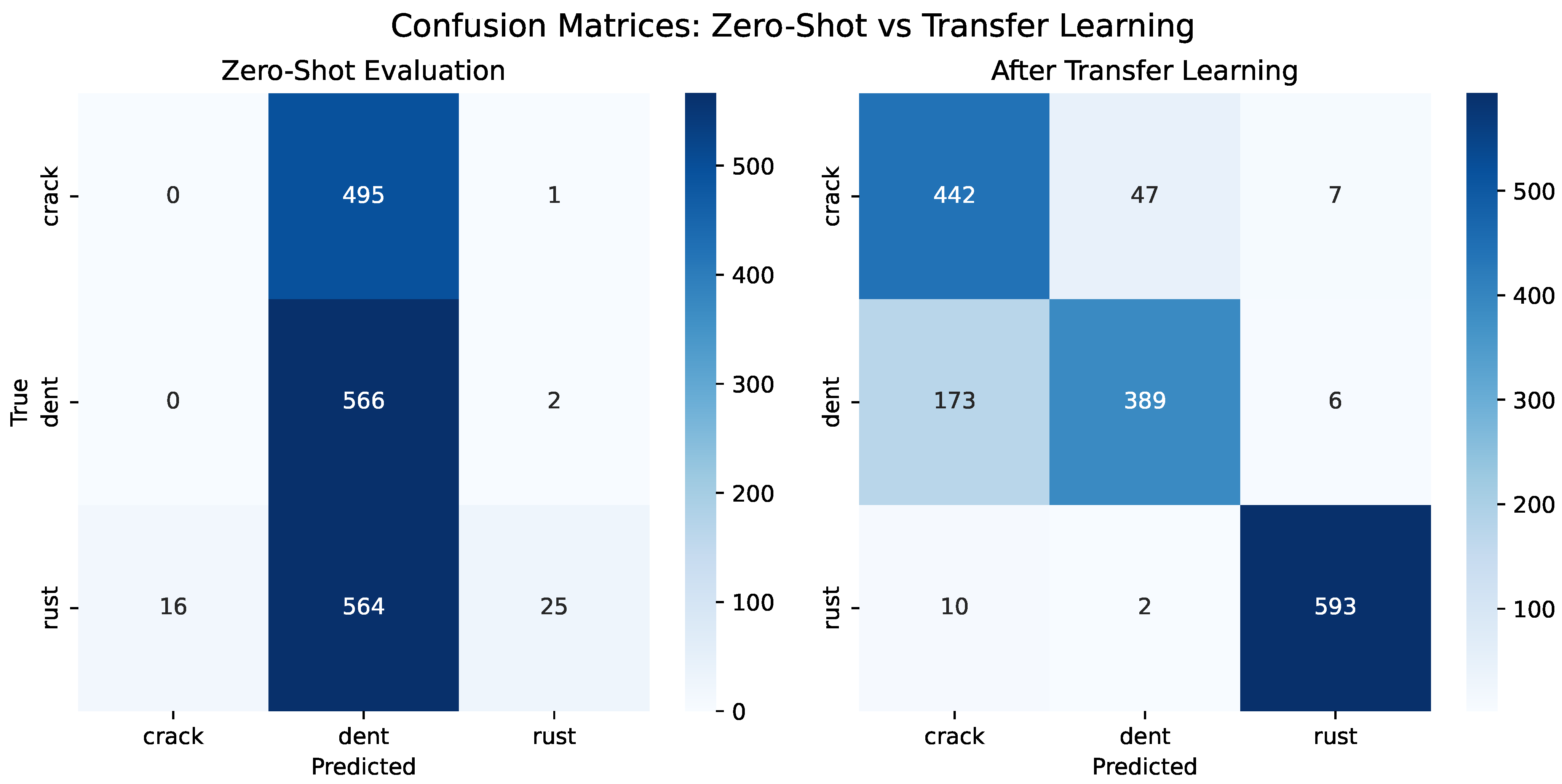

The confusion matrix generated on the aircraft test set

Figure 7 provides a granular view of classification performance.

Rust class exhibits near-perfect classification, with 593 out of 605 instances correctly identified.

Crack and Dent classes show moderate confusion, particularly with crack instances misclassified as dent.

The higher classification accuracy observed for the rust class can be attributed to its distinctive visual characteristics. Rust defects typically exhibit consistent reddish-brown color patterns and textured corrosion regions, which provide strong chromatic and appearance cues for the network. This misclassification for crack and dent likely stems from visual similarities such as shared linear edge textures or surface discontinuities, which challenge the separability without high resolution localization.

Despite these challenges, the confusion matrix confirms that the model has learned robust interclass distinctions post adaptation.

5. Qualitative Interpretation

5.1. PCA: Feature Embedding Evolution

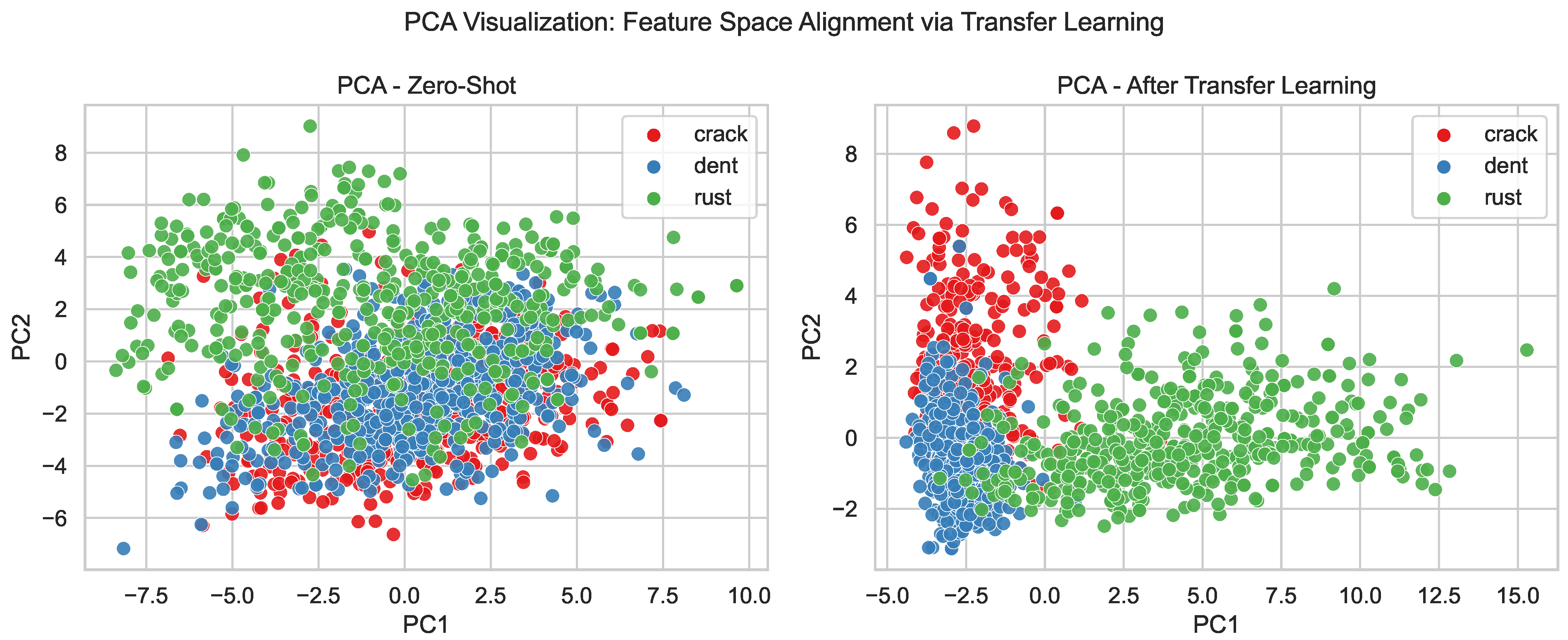

To analyse how the model’s internal representations evolve under domain shift, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is employed as a qualitative interpretability tool on feature embeddings extracted from the penultimate layer (post–Global Average Pooling). These embeddings capture a high-level semantic encodings crucial for classification. Feature space visualization using PCA as shown in

Figure 8 confirmed that post-adaptation embeddings became more compact and separable for each defect class, indicating effective domain alignment and improved cross-domain generalization.

(a) Zero-Shot Scenario:

Significant cluster overlap across crack, dent, and rust classes.

Absence of clear decision boundaries, indicating poor domain-invariant feature learning.

Evidence of feature collapse, a phenomenon typical of severe domain shift.

(b) Post Transfer Learning:

PCA reveals three well-separated clusters, each aligned with a defect class.

Increased intra-class compactness and improved inter-class separation.

Strong evidence that the model successfully adapts to the target domain.

Figure 6 additionally presents the class wise F1-score Comparision between zero-shot evaluation and post-transfer learning on the aircraft dataset. The most noticeable improvement is observed for defect classes such as cracks and corrosion-related patterns, which are highly sensitive to domain-specific texture variations, indicating that the proposed transfer-aware regularization is effective in improving cross-domain generalization.

To further examine the extent of domain shift and the need for adaptation, we performed a cross domain PCA on the penultimate layer embeddings obtained from the model trained solely on the metal dataset (i.e., before transfer learning). This projection includes features from both domains:

PCA in this case is has been used as an interpretative tool to explore features representation in domains providing a representation of the underlying domain shift that is easy to understand by projecting high dimensional representations of both the target data set and the source data set into a shared low dimensional space. PCA visualization showed well-separated clusters after adaptation, confirming stronger domain alignment. The visible difference in source-domain bias of the learned features and hence when the fine-tuning decreases overlap the semantic alignment between the domains is increased before transfer learning. This advancement demonstrates that the proposed framework supports acquisition of domain invariant yet defect discriminative representations, which explains its high cross domain generalization performance.

Together considering, the confusion matrix, within domain PCA, and cross domain PCA provide compelling evidence of domain shift and the model’s successful adaptation through fine-tuning. These visualizations affirm the critical role of CBAM and Progressive TDropBlock in:

Better categorization of defects that would offer a more suitable classification at the class level when there is a domain shift.

Semantic separability of defects based on smaller categorical groups, where reliable semantic representations are based on smaller and structured feature embeddings.

An increased resistance to low levels of supervision in the target area would indicate increased generalization in the case of cross domain inspection.

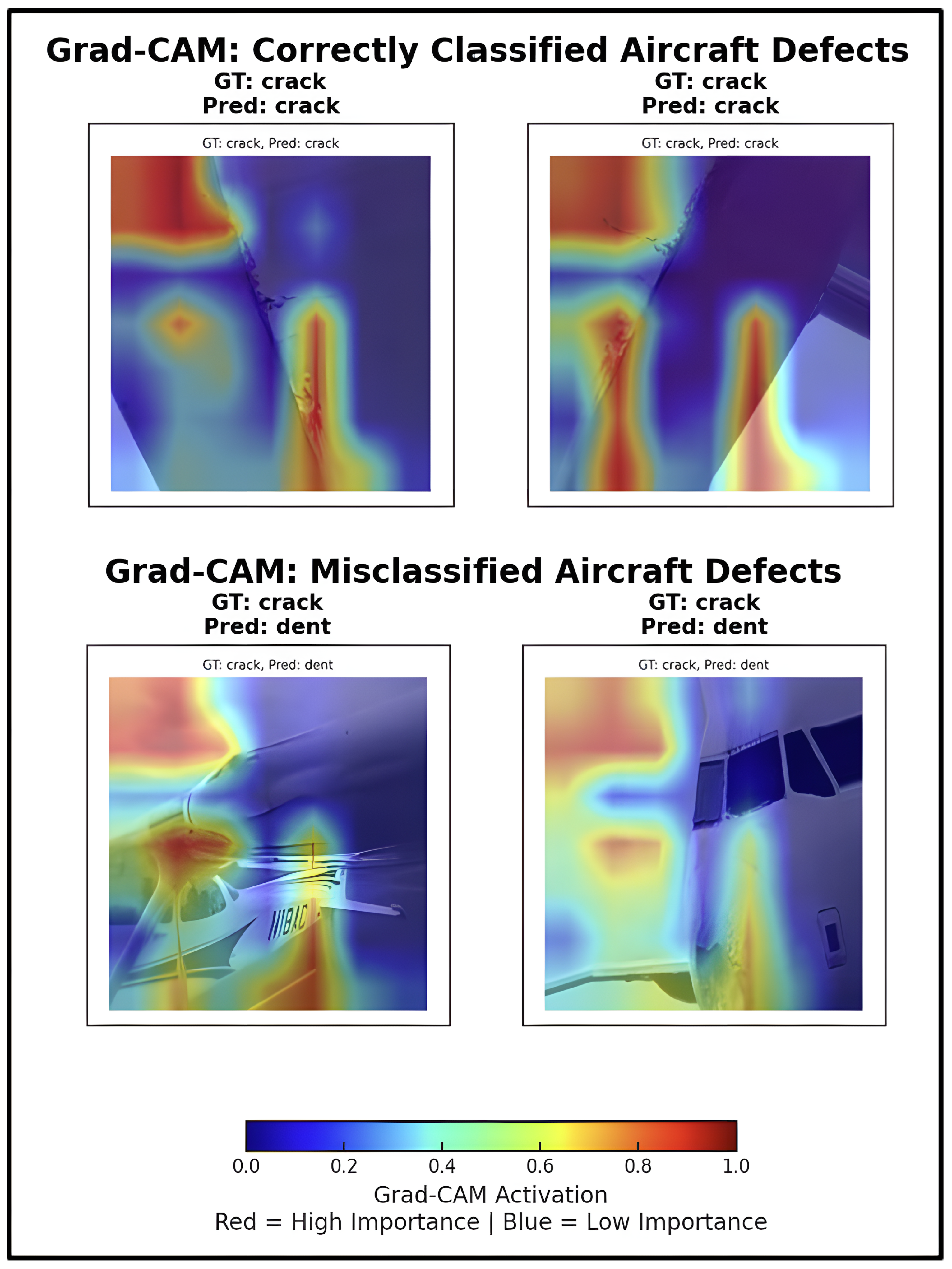

5.2. Interpretability via Grad-CAM

To enhance model interpretability and explain behaviour of misclassification, Grad-CAM heatmaps (

Figure 9) were regenerated for both correctly classified and misclassified samples, across various defect classes. Incorrectly predicted cases and high activation zones (red/yellow) completely aligned with true defect regions, which indicate that the model learned spatially meaningful features successfully. Grad CAM is used not only as a visualization tool but as an interpretability tool to investigate the effect of the proposed CBAM TDropBlock framework on feature attention, given cross-domain conditions. Through comparing activation maps of correct and incorrectly labeled samples, Grad-CAM will show whether the network concentrates on defect relevant areas or background domain-specific patterns. The analysis based on the proposed design gives qualitative evidence that the proposed design promotes more discriminative and transferable features learning, which contributes to the robustness of the model and its generalization of other visually dissimilar inspection fields. However, the misclassified samples frequently displayed scattered or distorted attention, concentrating solely on shadows or background textures instead of the cues that indicate localized defects. The visual evidence clarifies the ongoing confusion between classes that appear visually similar, such as cracks and dents. Furthermore, in certain incorrect instances, a partial focus on defect areas indicates that transfer learning has provided a beneficial inference bias. However, it may be essential to pursue extra fine-tuning or class-specific augmentation. In summary, these attention maps enhance the clarity and dependability of the proposed model within the context of real-world aircraft maintenance workflows.

5.3. Ablation Study

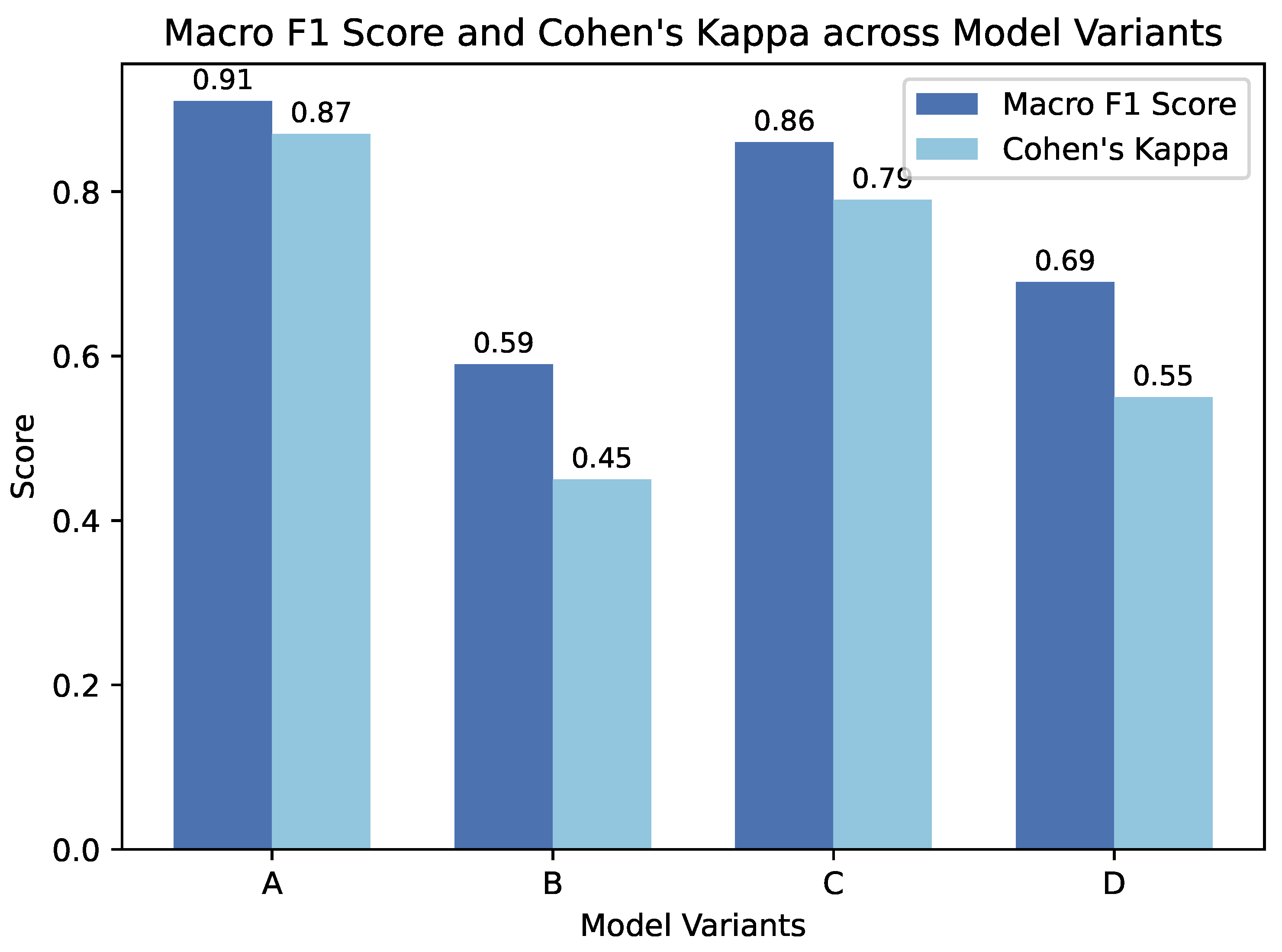

In order to quantitatively assess the individual and combined contributions of the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and the Progressive Transfer DropBlock (TDropBlock), a comprehensive ablation study was performed and results were summarised in

Table 5. The analysis showcases how each component and their combination contributes improvement in the model’s capability in domain shift generalization.

5.4. Key Observations

Variant A (CBAM + TDropBlock): variant ‘A’ achieved strongest results across all evaluation metrics, with values 91.06% accuracy, a 0.9122 Macro F1-Score, and a Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.866. These results clearly show that combining spatial attention along with adaptive dropout creates a very powerful synergy, especially considering situation when the model is tested across different domains.

Variant B (TDropBlock only): This particular variant, despite it offering a modest performance with gain in robustness but at the sametime falls short in discrimination capability. Its macro F1 Score (0.5906) and Kappa (0.445) indicate that the dropout alone, although the version is beneficial for regularization, but observed that, it is not sufficient enough for capturing defect-specific context.

Variant C (CBAM only): variant ‘c’ shows marked improvements over the baseline, substantiating the role of attention in class wise discrimination enhancement. The model highly benefits from refined localization of defect regions, improving feature saliency for subtle surface anomalies.

Variant D (Baseline - MobileNetV2 only): This variant is so far exhibits the lowest scores across all considered metrics, presenting the limited capacity of the backbone to handle domain shift without the support of attention or drop-out based regularization.

Overall, these results so far observed clearly demonstrate that both CBAM and TDropBlock contribute distinct yet complementary advantages. While CBAM improves spatial and channelwise feature localization, TDropBlock enforces structured regularization to promote generalizable learning. Their combination enables the model to not only differentiate between subtle classes but also maintain robustness under cross-domain settings.

Table 6 presents a comparison of lightweight architectures evaluated under identical training and evaluation conditions. The results show that the proposed framework provides consistent and substantial improvements for architectures with sufficient representational capacity, particularly MobileNetV2 [

32] and NASNetMobile [

33], which demonstrate clear gains across accuracy, macro-F1, and Cohen’s

. In contrast, extremely compact architectures exhibit limited or inconsistent benefits. For instance, SqueezeNet [

34] attains slightly higher accuracy and

value in its baseline configuration as compared to its proposed variant (0.670 vs. 0.660, 0.494 vs. 0.481), this difference is marginal and is accompanied by an substantial increase in macro-F1 (0.572 vs. 0.638). Another observation is that both SqueezeNet configurations perform substantially worse than MobileNetV2 integrated with the proposed framework, which achieves markedly higher and more stable performance across all metrics. This behavior is consistent with the design objective of SqueezeNet to aggressively reduce parameters and model size, which inherently constrains representational capacity and limits the effective integration of additional modules. Consequently, SqueezeNet’s marginal accuracy advantage does not translate into robust or balanced performance, and model selection based on overall reliability rather than isolated accuracy favors architectures such as MobileNetV2 when combined with the proposed framework.

5.5. Discussion

Results from Ablation study (

Figure 10) highlight the complementary roles of CBAM and TDropBlock in cross-domain defect classification: (i) CBAM enhances the location of defects by improving spatial attention and producing a higher macro F1-score; (ii) Whereas TDropBlock improves generalization by enforcing spatial regularization and increasing macro F1, Cohen’s Kappa; (iii) together, their combination (Variant A) delivers the best overall accuracy, confirming the synergy between attention and adaptive dropout.

MobileNetV2 enhanced with CBAM-TDropBlock improved accuracy from 35% (zero-shot) to 86% after transfer, while Cohen’s Kappa increased from 0.02 to 0.78, highlighting the benefit of limited target domain supervision. CBAM helped the network focus on subtle defect cues, such as crack edges and surface textures. In contrast, TDropBlock gradually suppressed dominant activations using inverted saliency masks, which encouraged the model to explore alternative regions and reduced overfitting. whereas TDropBlock progressively suppressed dominant activations via inverted saliency masks, encouraging exploration of alternate discriminative regions and reducing overfitting. Residual confusion between crack and dent arises from their similar elongated edges and low-contrast textures, adding class-specific or multi-scale attention heads may help disentangle them. TDropBlock adds negligible computational cost because it relies on depthwise convolutions, making the framework practical for real-time inspection on embedded devices such as drones or edge cameras. In addition, class-domain classification performance with different lightweight backbone evaluations shows comparable absolute accuracy, the proposed model consistently improves cross-domain robustness across all the tested architectures, indicating that the contribution lies in attention-guided regularization rather than backbone capacity. Although the method performs reliably under moderate domain differences, performance may degrade under extreme shifts (e.g., visible-to-thermal transitions or severe imbalance). Future extensions could incorporate unsupervised adaptation, adversarial learning, or domain-invariant constraints to improve robustness. In this context, a direct quantitative comparison with the prior studies is limited, as the aircraft defects dataset utilized in this study is not publicly available.

5.6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study proposed an Adaptive Attention DropBlock framework for domain-adaptive defect classification. By combining CBAM-based spatial attention with the novel TDropBlock regularizer inside a lightweight MobileNetV2 backbone, the model achieved large gains in cross-domain accuracy from 35% to 86% and reliability with Cohen’s Kappa value 0.78. Visualization through PCA and Grad-CAM confirmed enhanced feature separation and focused defect localization.The framework uniquely integrates adaptive attention-guided dropout with progressive depth scheduling, an approach not previously explored for real-time defect classification. This design increases spatial diversity, limits overfitting, and supports interpretable, edge-deployable performance. Remaining challenges include disambiguating visually similar defect types and extending adaptability to wider modality gaps. Future work will pursue unsupervised or adversarial adaptation and adaptive regularization to strengthen domain invariance and broaden industrial applicability. One could also investigate other schedules instead of linear growth rate in Algorithm 1.