1. Introduction

The past few years have witnessed a significant surge in the application of large language models (LLMs), followed by vision-language models (VLMs), in the field of medical research [

1,

2,

3,

4]. VLMs, a category of artificial intelligence (AI) utilizing deep learning, are designed to interpret and reason about visual and textual data simultaneously. The most widely known model to date is ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI [

5]. Since September 2023, ChatGPT has been augmented with vision capabilities, allowing it to analyze and interpret images alongside textual input [

6]. The first studies show that there is room for improvement compared to the current text function [

7,

8].

The intended use and clinical role for an AI approach in this context is to act as an assistive tool for radiologists and orthopedic surgeons. It could help streamline radiology workflow by pre-screening radiographs, flagging potential abnormalities, and providing preliminary interpretations, especially in settings with limited access to subspecialty expertise. Approximately 3% of all pediatric and adolescent cancer cases are attributable to malignant bone tumors [

9]. Among primary bone tumors, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma are the most prevalent [

10,

11]. While malignant tumors receive considerable attention, benign bone tumors are also of clinical significance, with osteochondromas being the most common, followed by giant cell tumors, osteoblastomas, and osteoid osteomas [

12,

13]. The rarity of these lesions poses a diagnostic challenge, as many radiologists may lack the experience needed to detect and evaluate them accurately on conventional radiographs [

14]. Deep learning (DL), a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) that recognizes complex patterns in large datasets, has shown great promise in detecting such lesions [

15,

16,

17]. More recently, there has been a rapid expansion of vision–language and foundation models in medical imaging, which aim to jointly learn from images and text and generalize across multiple radiologic tasks [

18,

19,

20]. In parallel, robustness-oriented methods have been proposed that focus on enhancing feature representations under adverse imaging conditions. For example, Li et al. introduced IHENet, an illumination-invariant hierarchical feature enhancement network for low-light object detection that improves performance in challenging scenes. Although designed for natural images, IHENet exemplifies hierarchical feature enhancement and illumination-invariant representation learning that could inspire more robust bone tumor analysis on X-ray imaging [

21].

The primary aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the diagnostic capabilities of VLMs in detecting and classifying bone tumors on conventional radiographs, using visual information alone. Our primary hypothesis was that VLMs could achieve clinically relevant accuracy in tumor detection and classification. Model performance was assessed across five clinically relevant tasks: tumor detection, classification, tumor type identification, anatomical region recognition, and X-ray view classification. In addition to evaluating diagnostic accuracy, the study investigated whether self-reported certainty scores could serve as a meaningful indicator of prediction correctness. Furthermore, we explored the effect of adding basic demographic information—specifically patient age and sex—on model performance. We hypothesized that the inclusion of demographic data would improve diagnostic accuracy, particularly for age-dependent tumor types. Moreover, all models were evaluated using a standardized zero-shot prompt with a temperature of 0 to ensure reproducibility. This approach may disadvantage models that perform better with Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting or iterative interaction. Also, the dataset reflects class imbalances inherent to the source collection, which may skew performance metrics; for instance, frequent tumor types like osteochondroma are overrepresented compared to rare lesions. Lastly, we tested an ensemble strategy to determine whether combining multiple models could enhance diagnostic reliability. This comprehensive evaluation provides insights into the current potential and limitations of VLMs in musculoskeletal radiologic diagnostics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a retrospective study designed to evaluate the performance of existing AI models on a publicly available dataset. The study goal was to perform a feasibility study and exploratory analysis of several commercially available VLMs for the task of bone tumor diagnosis on radiographs.

2.2. Data

The data source for this study was the Bone Tumor X-ray Radiograph (BTXRD) dataset, a publicly available collection of anonymized radiographs with expert annotations, accessible at

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-024-04311-y (accessed on 27 May 2025). The images were collected as part of routine clinical care, though specific dates and locations of initial data collection are not detailed in the source dataset.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

All images from the BTXRD dataset were initially considered. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in our final study cohort were the presence of a single, unambiguous ground-truth label for each of the following categories: X-ray view, anatomical body region, tumor presence, tumor classification (benign/malignant), and specific tumor type.

2.4. Data Pre-Processing and Selection

Prior to model evaluation, the dataset underwent a rigorous filtering process to ensure data quality and remove ambiguity. This process constituted the selection of a data subset. Only cases with a single, unambiguous ground-truth label for each of the following categories were retained for analysis:

X-ray view (e.g., frontal, lateral, or oblique)

Anatomical body region (Upper limb/lower limb/pelvis location)

Tumor presence, if yes:

- (a)

Tumor classification (benign or malignant)

- (b)

Tumor type

- (c)

Tumor location

This filtering step resulted in a final cohort where each case had a single, definitive ground-truth label for all evaluated characteristics, ensuring a clear and objective basis for performance assessment. Data elements were defined based on the labels provided in the original BTXRD dataset. The dataset authors state that the images were de-identified prior to public release; no further de-identification methods were applied by us. No missing data were imputed; cases with missing or ambiguous labels were excluded during the filtering step.

2.5. Ground Truth

The ground truth reference standard was defined by the expert-annotated labels provided within the BTXRD dataset. The rationale for choosing this reference standard is that it represents a curated, publicly available benchmark that has undergone peer review. The original dataset paper specifies that annotations were performed by clinical experts. Details on the qualifications and specific preparation of the annotators or the annotation tools used are provided in the source publication for the BTXRD dataset. The original dataset creators did not provide measurements of inter- and intrarater variability or methods to resolve discrepancies, which is a limitation of the source data.

2.6. Data Partitions

This study did not involve training a new model; therefore, data was not partitioned into traditional training, validation, and testing sets. The entire filtered dataset of 3746 images was used as a single test set to evaluate the performance of the pre-trained, commercially available VLMs. The intended sample size was the maximum number of high-quality, unambiguously labeled images available from the source dataset after filtering.

2.7. Models

Six commercially available large language models (LLMs) were evaluated: Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro Preview (5 June 2025) and Gemini 2.5 Flash Preview (20 May 2025), Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4 (14 May 2025), and OpenAI’s GPT-4.1 (14 April 2025), GPT-4o Mini, and GPT-o3 (16 April 2025). These models are vision-language models that take an image and a text prompt as input and generate a structured JSON text as output. The internal architectures (intermediate layers and connections) of these commercial models are proprietary and not publicly detailed. All models were accessed via the HyprLab API gateway (

https://hyprlab.io/ (accessed on 27 May 2025)).

2.8. Evaluation

To maximize determinism and reproducible outputs, the temperature for all model inferences was set to 0.0, with a maximum token output of 1024. For each image, the models were provided with a consistent system prompt defining their role as an expert radiologist. The user prompt instructed the models to perform five clinical tasks. Outputs were returned in a structured JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) format, which included all available class labels per category to enable automated analysis. The prompt was as follows:

You are an expert radiologist specializing in X-ray interpretation.

Carefully examine the provided X-ray image and extract the following information in a structured JSON format:

Identify the anatomical view or projection (e.g., frontal, lateral, oblique). Specify the body region depicted in the image. Determine whether a tumor or abnormal growth is present. - –

If present, classify the tumor (benign or malignant), specify the tumor type, and indicate its anatomical location.

Assign a certainty score to your analysis (from 0 [completely uncertain] to 1 [completely certain]).

Base your assessment strictly on the visual evidence in the image. Be concise, accurate, and avoid speculation. Return only the structured JSON output as specified by the schema. |

To assess the impact of patient context, two experimental conditions were tested for each model on each image: (1) analysis of the X-ray image alone, and (2) analysis of the X-ray image supplemented with patient demographic information (age and sex). Whenever a model was overly specific, the specific term was mapped to the general category (e.g., “foot” was mapped to “lower limb”). The mapping rules are documented in the

Appendix A.

2.9. Creation of the Gemini Ensemble Model

To explore the potential of combining model strengths, a “Gemini Ensemble” model was created by integrating the predictions of Gemini 2.5 Pro and Gemini 2.5 Flash. The ensembling strategy was determined empirically by comparing multiple fusion approaches. For the primary task of tumor detection, three strategies were evaluated:

High-Recall (OR logic): The ensemble predicts a tumor if either model detects one.

High-Precision (AND logic): The ensemble predicts a tumor only if both models detect one.

Certainty-Weighted: The ensemble adopts the prediction of the model with the higher self-reported certainty score.

The strategy yielding the highest F1 score for tumor detection was selected for the final ensemble model. For classification tasks (tumor classification, tumor type, body region, and X-ray view), we compared four fusion strategies: (1) certainty-weighted voting, (2) majority voting with certainty-based tie-breaking, (3) Gemini Pro predictions only, and (4) Gemini Flash predictions only. For a two-model ensemble, majority voting reduces to agreement-based selection with a tie-breaker when models disagree; we used certainty scores as the tie-breaker to maintain consistency. The comparison revealed that certainty-weighted and majority voting yielded identical results, while single-model performance varied by task (

Table A2).

2.10. Statistical Analysis and Performance Metrics

Model performance was evaluated across the five clinical tasks using metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F1 score. The F1 score was considered the key metric for the tumor detection task due to its balanced assessment of precision and recall. To evaluate the impact of including demographic data, paired t-tests were performed to compare model accuracy on each task under the “with demographics” (providing age and sex of the patient) versus “without demographics” conditions. Statistical measures of uncertainty were calculated as 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the mean differences. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The correlation between model-reported certainty scores and actual accuracy was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. A robustness analysis was performed by evaluating performance with and without demographic data. The unit of analysis was the individual radiographic image. Due to the anonymized nature of the dataset, clustering by patient identity was not possible. No specific methods for explainability or interpretability (e.g., saliency maps) were evaluated in this study, as the focus was on diagnostic output accuracy. All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R (version 4.3) with the tidyverse, ggplot2, and gt packages.

4. Discussion

This study represents one of the first systematic evaluations of VLMs in the context of musculoskeletal tumor diagnostics using radiographs. By analyzing multiple commercially available models across a range of clinically relevant tasks, we provide novel insights into the capabilities, limitations, and calibration of current VLMs in a real-world medical imaging scenario. Our findings highlight both promising use cases and critical challenges that must be addressed before broader clinical adoption is feasible.

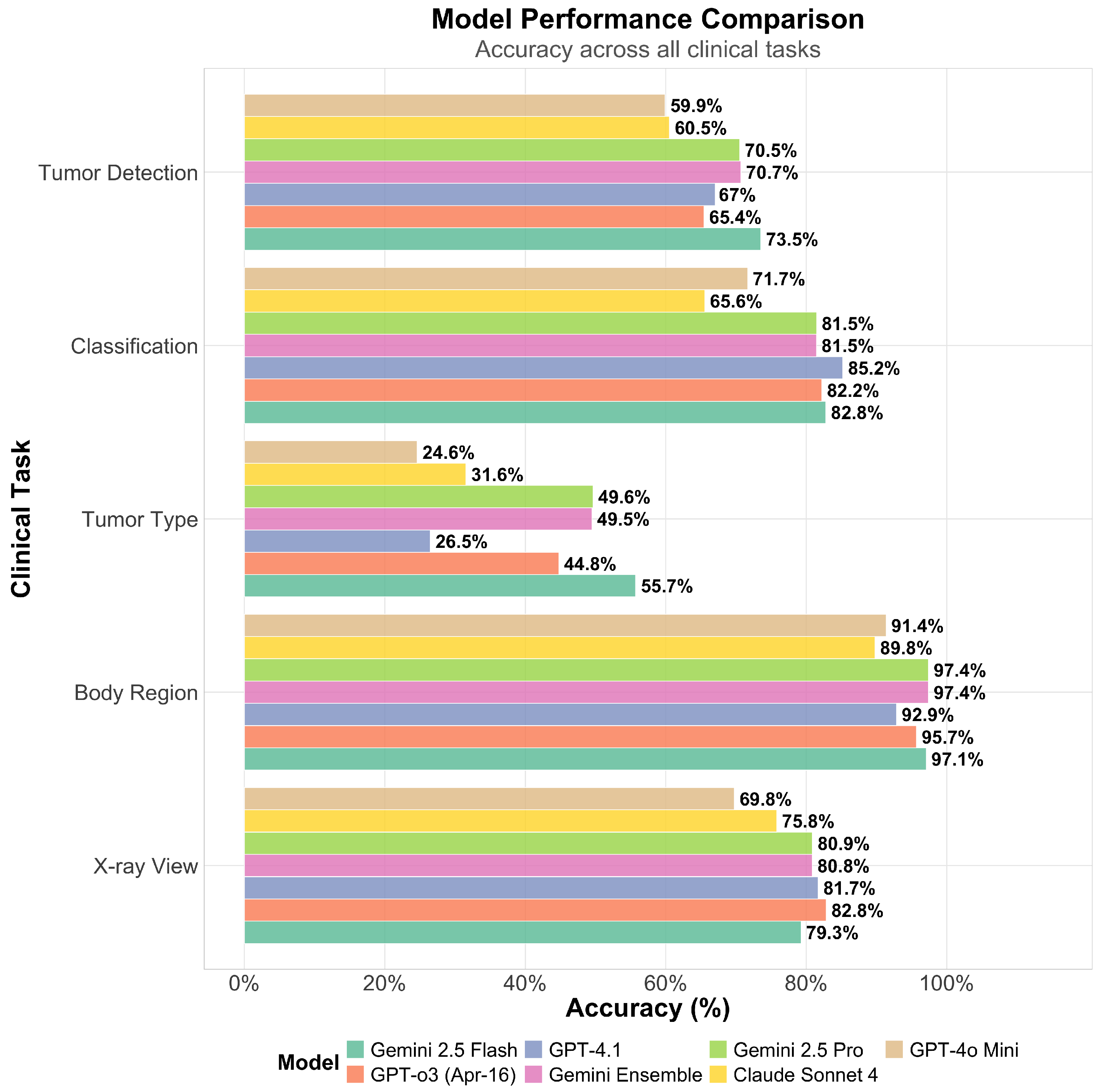

All models performed well in basic image classification tasks such as anatomical region (up to 97.4%) and X-ray view identification (up to 82.8%). At their best, the VLMs achieved performance levels that were comparable to, although in many cases lower, those of deep learning models specifically trained for this task [

22,

23]. For more complex tasks such as tumor detection, the models demonstrated overall poor performance, achieving accuracies of up to only 73.5%, which is notably lower than the >90% accuracy reported in previous studies using dedicated deep learning approaches [

24,

25]. It is noteworthy that prior studies were limited to a single anatomical region, while VLMs, although less accurate, offer greater flexibility for use across a wider range of anatomical sites [

25,

26]. Compared to a previously conducted study on the classification of different primary bone tumors from X-ray images at different anatomical locations, which yielded an accuracy of 69.7% using a multimodal deep learning model, the VLMs in our study—like Gemini Flash 2.5—achieved a slightly lower performance (55.7% for tumor type classification) [

27]. When considering only the distinction between benign and malignant tumors, the VLMs demonstrated performance comparable to that of musculoskeletal fellowship-trained radiologists and exceeded the performance of radiology residents [

28]. Although Gemini 2.5 Flash is less powerful and less expensive than the Pro version, it outperformed the Pro version in this study [

29,

30]. The reasons for the different performance of the models should be investigated further in future studies.

The overall results indicate that VLMs are capable of delivering solid diagnostic performance, even without task-specific training. This suggests considerable potential for adaptation and improvement through fine-tuning and future advances in model architecture and multimodal integration, which could further enhance their clinical utility. A recent study by Ren et al. assessed the diagnostic performance of GPT-4 in classifying osteosarcoma on radiographs. Using a binary classification setup with 80 anonymized X-ray images, the model showed limited sensitivity for malignant lesions. Osteosarcoma was correctly identified as the top diagnosis in only 20% of cases and was at least mentioned among the possible diagnoses in 35% [

31]. These results highlight the challenges of malignancy recognition for current VLMs in clinical imaging. In contrast, our study evaluated a broader range of musculoskeletal tumors across multiple anatomical regions and found higher diagnostic accuracy, particularly in tumor detection. The best-performing ensemble model achieved a recall of 0.822 and an F1 score of 0.723, indicating a more balanced and clinically useful performance. However, both studies confirm that tumor type classification remains a major limitation, and that VLMs, while improving, should not yet replace expert radiologists in high-stakes diagnostic tasks. This is further underscored by a recent reader study in which two radiologists specialized in musculoskeletal tumor imaging achieved accuracies of 84% and 83% at sensitivities of 90% and 81%, respectively, clearly outperforming both an artificial neural network and non-subspecialist readers on the same benign–malignant classification task. To place these findings in a clinical context, radiologists interpreting bone tumors on radiographs have been reported to achieve substantially higher sensitivity for distinguishing malignant from benign or infectious lesions (e.g., sensitivities around 93–98%) (PMID: 31850149), and recent task-specific deep learning models for bone tumor detection or classification can approach or even match such expert performance on selected tasks [

32]. In contrast, the sensitivity and F1 scores observed for the general-purpose VLMs in our study fall clearly below such thresholds and would be insufficient for any system that could miss malignant lesions. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that, in their current form, general-purpose vision–language models are not suitable for autonomous diagnostic interpretation in clinical practice and should be regarded as exploratory research tools only.

In addition to evaluating model accuracy, our study also assessed the calibration of VLMs by analyzing the correlation between self-reported certainty and diagnostic correctness. While Gemini Pro demonstrated a weak but positive correlation (r = 0.089), indicating that higher certainty was slightly associated with better performance, all other models showed a weak negative correlation. This suggests that many VLMs are overconfident, even when incorrect, which poses a critical concern in clinical contexts where reliability and transparency are essential. Beyond image interpretation, current research also explores whether LLMs can assess their own confidence when generating responses. This self-evaluation capability is crucial in medical applications, where overconfidence can lead to misinformed decisions. A recent study demonstrated that even state-of-the-art models such as GPT-4o show limited differentiation in confidence levels between correct and incorrect answers [

33]. Self-evaluation may even help improve the accuracy of the responses [

34]. These findings highlight a critical limitation of current LLMs in safety-sensitive domains like healthcare and emphasize the need for improved methods of uncertainty estimation before broader clinical integration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate image-based recognition, diagnostic accuracy and self-assessment of large-scale language models in a real-world clinical setting.

We also investigated whether providing demographic context (age and sex) improved diagnostic performance. While the inclusion of this information led to a statistically significant increase in tumor detection accuracy (+1.8%, p < 0.001), it had no meaningful effect on more complex classification tasks such as tumor type or malignancy status. To date, no published studies have systematically examined the influence of demographic information on the diagnostic output of VLMs. However, given that demographic factors such as age and sex can substantially affect the likelihood and presentation of specific tumors and diseases, their consideration represents an important aspect of real-world clinical decision-making.

Nevertheless, VLMs can have practical value as an aid, particularly for triage or second opinions in resource-constrained settings. For low-risk applications, such as providing differential diagnoses, even moderate accuracy and good calibration can offer meaningful benefits. In contrast, high-risk applications—such as autonomous primary diagnoses in musculoskeletal tumor imaging—require near-expert performance and robust reliability. Our results suggest that current VLMs do not yet meet these higher requirements and should therefore remain limited to complementary tasks within carefully controlled clinical workflows. Future work should focus on improving model calibration, incorporating multimodal data sources (e.g., clinical history, lab results), and validating performance in real-world, heterogeneous clinical environments.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, potential bias exists as the evaluation was performed on a single, curated public dataset, which may not fully represent the diversity of clinical presentations and image quality seen in practice. The generalizability of our findings is therefore not guaranteed. Second, all models were evaluated using a standardized prompt format, which limits the assessment of model flexibility and adaptability to different instruction styles. Third, we deliberately restricted clinical context to the minimal demographic variables available in the BTXRD dataset, namely age and sex. This design choice allowed us to isolate how limited demographic information modulates otherwise purely image-based VLM performance. A broader multimodal evaluation that integrates richer clinical metadata (e.g., medical history, laboratory values, follow-up imaging) lies beyond the scope of the present work and should be addressed in future studies. Fourth, the dataset consisted of clearly labelled cases with unambiguous ground-truth annotations, which may not reflect the diagnostic ambiguity frequently encountered in clinical practice. As such, the generalizability of these findings to more complex or borderline cases remains uncertain. Finally, no comparison was made to human radiologists, so it remains unclear how current VLM performance benchmarks against expert-level clinical interpretation.