Use of Artificial Intelligence in Burn Assessment: A Scoping Review with a Large Language Model-Generated Decision Tree

Abstract

1. Introduction

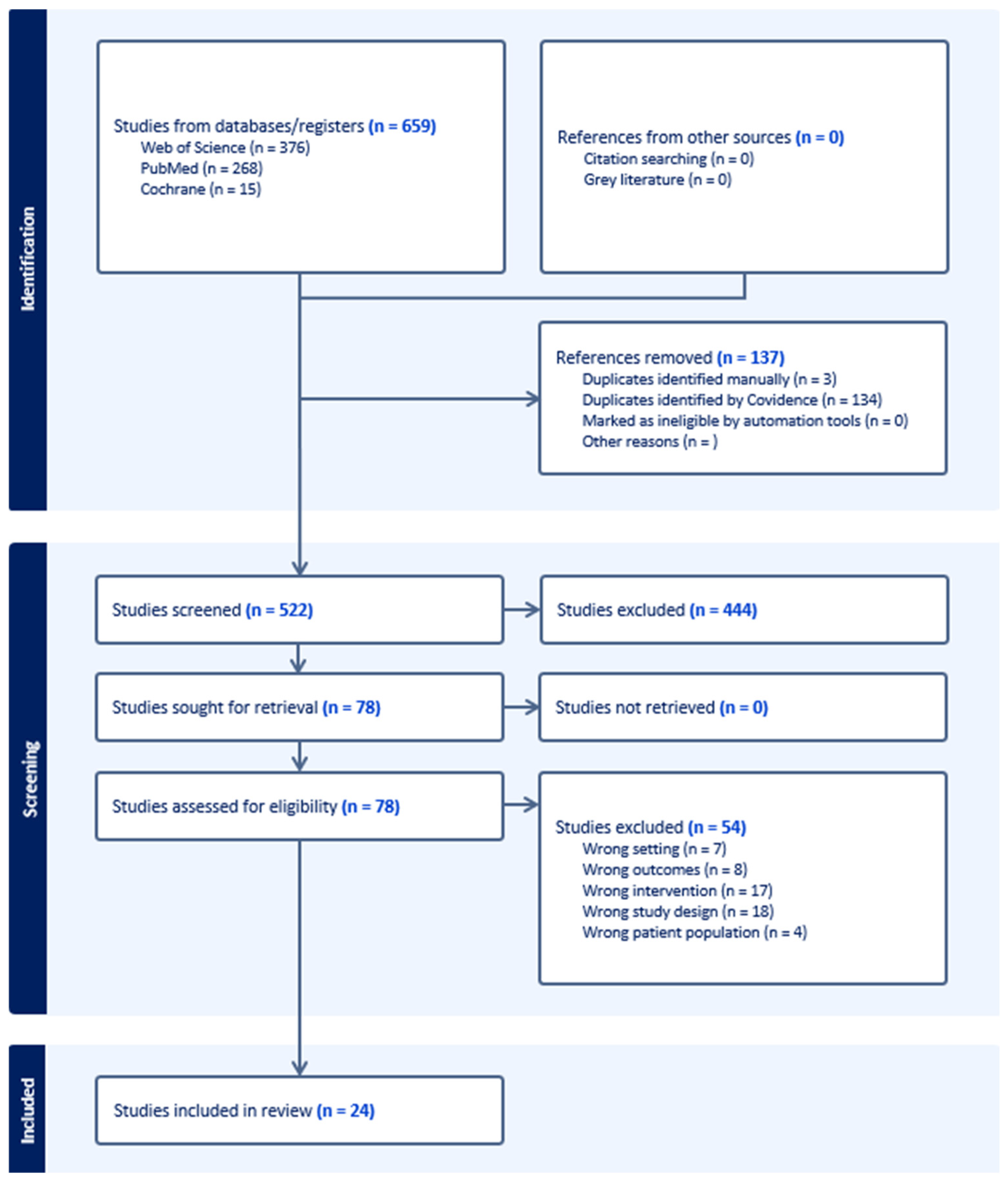

2. Methods

- Written in English.

- Reported use of CNN for analysis of two-dimensional burn images.

- Reported quantitative model performance metrics.

- Exclusion criteria:

- Not focused on burn assessment tasks (TBSA, burn depth or treatment-related tasks).

- Did not use CNN-based methods.

- Did not report quantitative performance metrics.

- Conference abstracts, editorial, letters, protocols or non-peer-reviewed records.

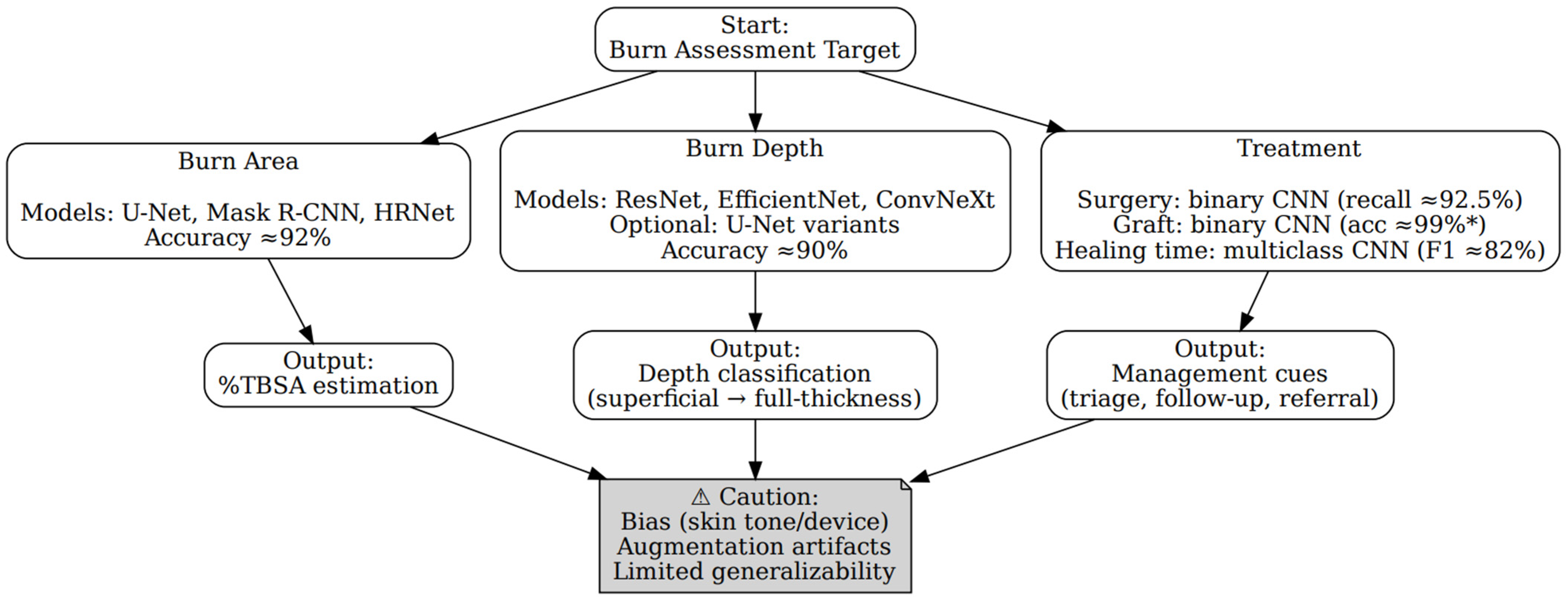

LLM-Derived Decision Model

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Included Studies

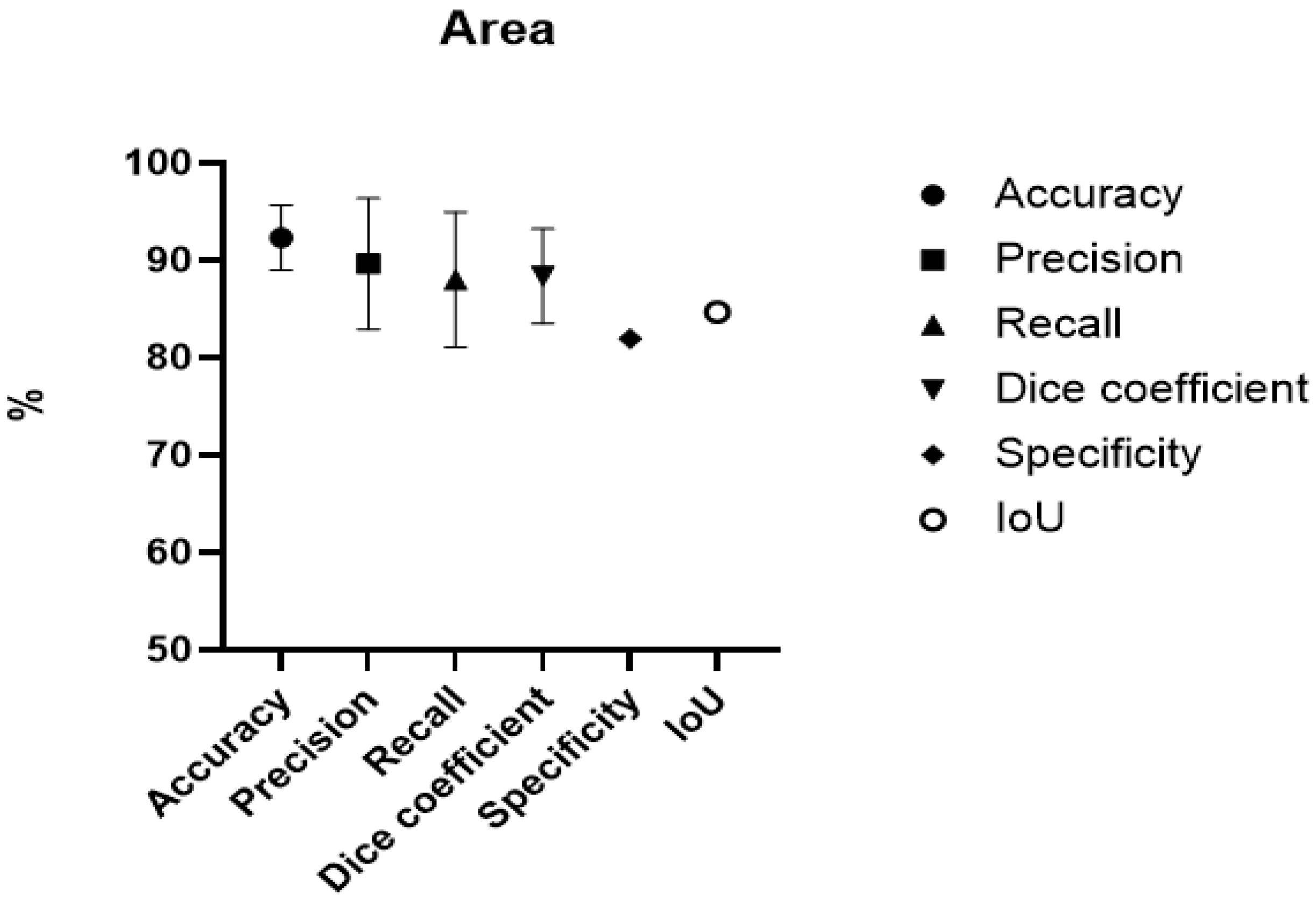

3.2. Burn Area

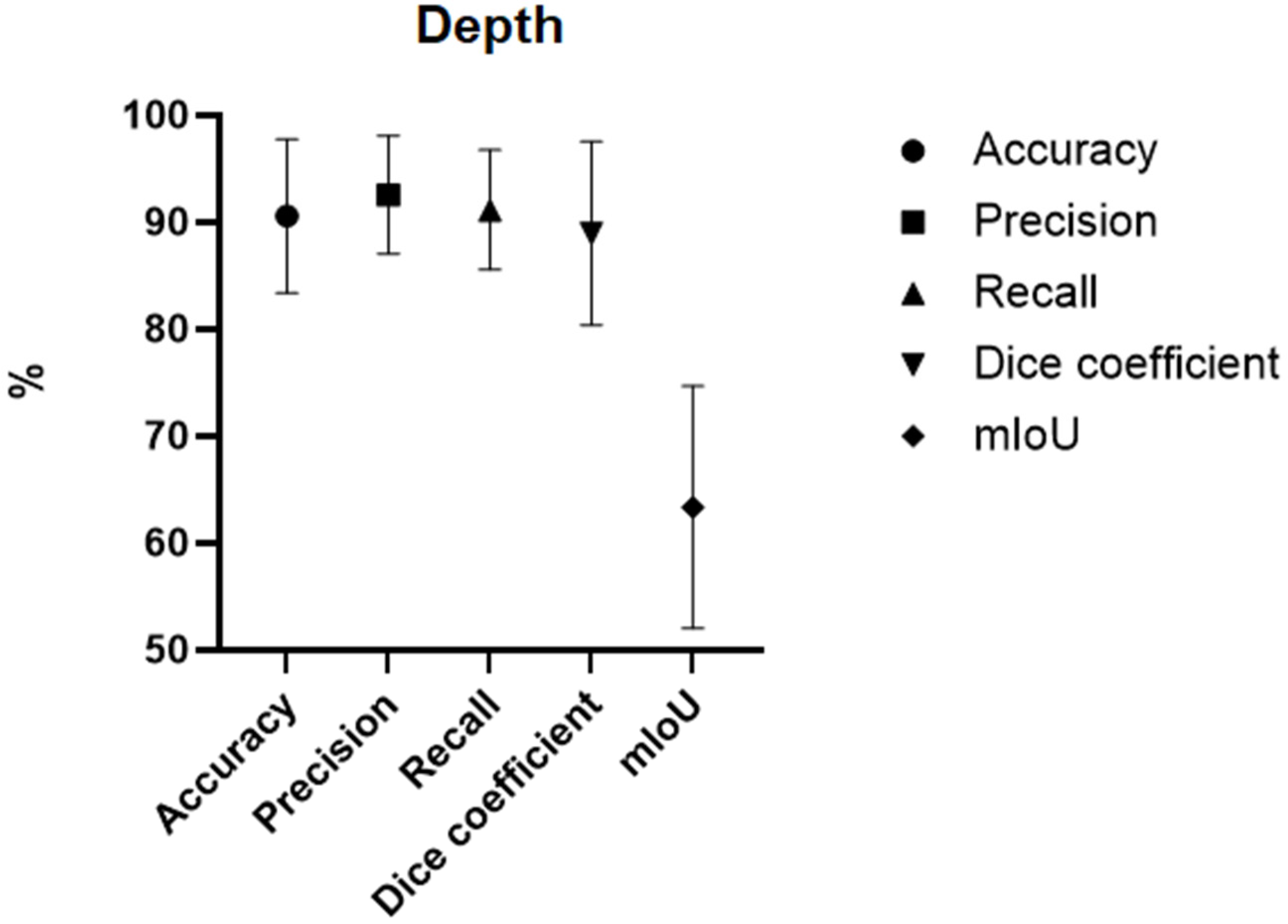

3.3. Burn Depth

3.4. Treatment

3.5. Large Language Model Evaluation

3.5.1. ChatGPT

3.5.2. Evaluation of the LLM Decision Tree

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Burns. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Rybarczyk, M.M.; Schafer, J.M.; Elm, C.M.; Sarvepalli, S.; Vaswani, P.A.; Balhara, K.S.; Carlson, L.C.; Jacquet, G.A. A systematic review of burn injuries in low- and middle-income countries: Epidemiology in the WHO-defined African Region. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. Rev. Afr. Med. D’urgence 2017, 7, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, H.A.; Holmes Iv, J.H.; Hickerson, W.L.; Cockerell, C.J.; Shupp, J.W.; Carter, J.E. Use of 816 Consecutive Burn Wound Biopsies to Inform a Histologic Algorithm for Burn Depth Categorization. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2021, 42, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocco-Tussardi, I.; Presman, B.; Huss, F. Want Correct Percentage of TBSA Burned? Let a Layman Do the Assessment. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2018, 39, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y. Progress in the application of artificial intelligence in skin wound assessment and prediction of healing time. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 2765–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Ray, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Shukla, K.K.; Pradhan, S.; Aggarwal, L.M. Segmentation and classification of medical images using texture-primitive features: Application of BAM-type artificial neural network. J. Med. Phys. 2008, 33, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G.; Jordan, M.; Ilono, P. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Review. Information 2025, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimundić, A.M. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy: Basic Definitions. eJIFCC 2009, 19, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yue, K.; Cheng, S.; Li, W.; Fu, Z. A Framework for Automatic Burn Image Segmentation and Burn Depth Diagnosis Using Deep Learning. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 5514224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Shamseer, L.; Tricco, A.C. Registration of systematic reviews in PROSPERO: 30,000 records and counting. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, F.; Zhang, D.; Su, K.; Xin, N. Burn Images Segmentation Based on Burn-GAN. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2021, 42, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.W.; Lai, F.; Christian, M.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsu, C.; Chen, Y.S.; Chang, D.H.; Roan, T.L.; Yu, Y.C. Deep Learning-Assisted Burn Wound Diagnosis: Diagnostic Model Development Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e22798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, J.; Goyal, P. Convolution neural network for effective burn region segmentation of color images. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2021, 47, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissin, C.; Laflamme, L.; Fransén, J.; Lundin, M.; Huss, F.; Wallis, L.; Allorto, N.; Lundin, J. Development and evaluation of deep learning algorithms for assessment of acute burns and the need for surgery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bu, Q.; Xie, J.; Li, H.; Xu, F.; Li, J. On-site burn severity assessment using smartphone-captured color burn wound images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 182, 109171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahnejad, M.; Lee, J.; Chan, H.; Morzycki, A.; Ethier, O.; Mo, A.; Liu, P.X.; Wong, J.N.; Hong, C.; Joshi, R. Novel CNN-Based Approach for Burn Severity Assessment and Fine-Grained Boundary Segmentation in Burn Images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5009510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabitha, C.; Vanathi, B. Densemask RCNN: A Hybrid Model for Skin Burn Image Classification and Severity Grading. Neural Process. Lett. 2021, 53, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabitha, C.; Vanathi, B. Dense Mesh RCNN: Assessment of human skin burn and burn depth severity. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 1331–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, O.; O Chan, H.; Abdolahnejad, M.; Morzycki, A.; Tchango, A.F.; Joshi, R.; Wong, J.N.; Hong, C. Using Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence to Track the Healing of Severe Burns. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2024, 45, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Abdolahnejad, M.; Morzycki, A.; Freeman, T.; Chan, H.; Hong, C.; Joshi, R.; Wong, J.N. Comparing Artificial Intelligence Guided Image Assessment to Current Methods of Burn Assessment. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2025, 46, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, M.D.; Mirdell, R.; Sjöberg, F.; Pham, T.D. Time-Independent Prediction of Burn Depth Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2019, 40, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Tong, X.; Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; Song, A.; Ji, S. GL-FusionNet: Fusing global and local features to classify deep and superficial partial thickness burn. Math. Biosci. Eng. MBE 2023, 20, 10153–10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Xie, J. Semi-Supervised Burn Depth Segmentation Network with Contrast Learning and Uncertainty Correction. Sensors 2025, 25, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, M.D.; Mirdell, R.; Sjöberg, F.; Pham, T.D. Improving burn depth assessment for pediatric scalds by AI based on semantic segmentation of polarized light photography images. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2021, 47, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabitha, C.; Vanathi, B. FASTER–RCNN for Skin Burn Analysis and Tissue Regeneration. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2022, 42, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suha, S.A.; Sanam, T.F. A deep convolutional neural network-based approach for detecting burn severity from skin burn images. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2022, 9, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Ugail, H.; Bukar, A.M. Assessment of Human Skin Burns: A Deep Transfer Learning Approach. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2020, 40, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam Khan, F.; Butt, A.U.R.; Asif, M.; Ahmad, W.; Nawaz, M.; Jamjoom, M.; Alabdulkreem, E. Computer-aided diagnosis for burnt skin images using deep convolutional neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 34545–34568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Ugail, H.; Smith, K.M.; Bukar, A.M.; Elmahmudi, A. Burns Depth Assessment Using Deep Learning Features. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2020, 40, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.P.; Jalal, A.S.; Prakash, V. Human burn depth and grafting prognosis using ResNeXt topology based deep learning network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 18897–18914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.P.; Aljrees, T.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Singh, K.U.; Singh, T. Spatial attention-based residual network for human burn identification and classification. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ke, Z.; He, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, P.; Li, T.; Zhou, J.; Li, F.; Yang, C.; et al. Real-time burn depth assessment using artificial networks: A large-scale, multicentre study. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2020, 46, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review Summary|Use of AI in Burns|Covidence. Available online: https://app.covidence.org/reviews/578850 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Dense Mesh RCNN: Assessment of Human Skin Burn and Burn Depth Severity|The Journal of Supercomputing. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11227-023-05660-y (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Müller, D.; Soto-Rey, I.; Kramer, F. Towards a Guideline for Evaluation Metrics in Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studies | 24 |

|---|---|

| Design | |

| Comparative | 12 |

| Experimental | 12 |

| Reported outcome | |

| Burn area (%TBSA) | 10 |

| Burn depth assessment | 17 |

| Treatment | 4 |

| Author/Title/Year | Country | Study Design | AI Model | Dataset (# of Images) | Training Set (# of Images) | Summary Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dai et al. 2021 [14] Burn Images Segmentation Based on Burn-GAN | China | Comparative study | Burn-GAN architecture that synthesizes realistic images | 1150 | 1000 + 960 generated | Accuracy = 96.88% Precision = 90.75% DC = 84.5% to 89.3% |

| Chang et al. 2021 [15] Deep Learning-Assisted Burn Wound Diagnosis: Diagnostic Model Development Study. | Taiwan | Comparative study | U-Net or Mask R-CNN with ResNet50 or ResNet101 | 2591 | 2073 (8:1:1, 80% train, 10%validation, 10% test.) | Accuracy = 91.30% Precision = 96.13% Recall = 93.90% |

| Chauhan et al. 2021 [16] Convolution neural network for effective burn region segmentation of colour images. | India | Experimental study | ResNet101 | 434 | 316 | Accuracy = 93.36% Precision = 81.95% Recall = 83.39 Specificity = 95.70% DC = 81.42% |

| Boissin et al. 2023 [17] Development and evaluation of deep learning algorithms for assessment of acute burns and the need for surgery. | Sweden, South Africa | Experimental study | Aiforia Create self-service deep learning tool | 1105 + 536 background | 773 | Accuracy = 86.9% Precision = 83.4% DC = 82.9% Recall Darker Skin = 89.3% Recall Lighter skin = 78.6% |

| Liu et al. 2021 [11] A Framework for Automatic Burn Image Segmentation and Burn Depth Diagnosis Using Deep Learning. | China | Experimental study | ResNet-50 with ResNEt-101 modified to HRNetV2 | 516 + 1200 expanded | 960 | IOU = 84.67% DC = 91.70% |

| Xu et al. 2024 [18] On-site burn severity assessment using smartphone-captured color burn wound images. | China | Comparative study | ResNet and ResNeXt modified to ConvNeXt | 917 | Evaluated with 6-fold cross-validation | DC = 85.36% R2 for %TBSA = 91.36% |

| Abdolahnejad et al. 2025 [19] Novel CNN-Based Approach for Burn Severity Assessment and Fine-Grained Boundary Segmentation in Burn Images | Canada | Experimental study | EfficientNet B7 | 1385 + 184 LDPI images | 1385 | Accuracy = 91.39% |

| Pabitha et al. 2021 [20] Densemask RCNN: A Hybrid Model for Skin Burn Image Classification and Severity Grading | India | Comparative study | ResNet-101 and DenseMask RCNN | 1800 | 1200 | DC = 87.10% |

| Pabitha et al. 2024 [37] Dense Mesh RCNN: assessment of human skin burn and burn depth severity | India | Comparative study | ResNet-101 and Dense Mesh RCNN | 1150 | 1000 | Accuracy = 94.10% Precision 95.90% Recall = 94.80% DC = 95.30% |

| Author/Title/Year | Country | Study Design | AI Model | Dataset (# Images) | Training Set (# Images) | Summary Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethier et al. 2024 [22] Using Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence to Track the Healing of Severe Burns. | Canada | Experimental study | EfficientNet B7 | 1559 | 1285 | Recall = 82% Precision = 83% DC = 82% |

| Lee et al. 2025 [23] Comparing Artificial Intelligence Guided Image Assessment to Current Methods of Burn Assessment. | England | Comparative study | EfficientNet B7 modified integration of Boundary attention mapping (BAM) | 1868 | 1684 | Area under the curve (AUC) = 85% |

| Cirillo et al. 2019 [24] Time-Independent Prediction of Burn Depth Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. | England | Comparative study | ResNet50 ResNet101 | 23 expanded to 676 | 10-fold cross-validation | Accuracy ResNet50 = 77.79% ResNet101 = 81.66% |

| Li et al. 2023 [25] GL-FusionNet: Fusing global and local features to classify deep and superficial partial thickness burn. | China | Comparative study | U-Net With fusion of ResNet50 and ResNet101 | 500 expanded to 3264 | 5-fold cross-validation | Accuracy = 93.52% Recall = 93.67% Precision = 93.51% DC = 93.51% |

| Liu et al. 2021 [11] A Framework for Automatic Burn Image Segmentation and Burn Depth Diagnosis Using Deep Learning. | China | Experimental study | ResNet-50 with ResNet-101 modified to HRNetV2 | 516 expanded to 1200. | 960 | IoU = 51.44% Accuracy = 66.84% DC = 68.82% |

| Zhang et al. 2025 [26] Semi-Supervised Burn Depth Segmentation Network with Contrast Learning and Uncertainty Correction. | China | Comparative study | U-Net modified to semi-supervised model SBCU-net | 1142 | 914 | 50% labelled data: Accuracy = 94.32% DC = 84.51% mIoU = 74.04% 10% labelled data Accuracy = 92.10% DC = 76.95% mIoU = 64.58% |

| Cirillo et al. 2021 [27] Improving burn depth assessment for paediatric scalds by AI based on semantic segmentation of polarized light photography images. | Sweden, Saudi Arabia | Experimental study | Modified U-Net | 100 | 16 | Accuracy = 91.89% DC = 91.88% |

| Pabitha et al. 2022 [28] FASTER-RCNN for Skin Burn Analysis and Tissue Regeneration | India | Comparative study | R-CNN modified to Faster RCNN | 1300 | 1000 | Recall = 89.60% Precision = 98.46% DC = 95.20% |

| Abdolahnejad et al. 2025 [19] Novel CNN-Based Approach for Burn Severity Assessment and Fine-Grained Boundary Segmentation in Burn Images | Canada | Experimental study | ImageNet modified to EfficientNet B7 EfficientNet B7 | 1385 + 184 LDPI images | 1385 | Accuracy 80% |

| Suha et al. 2022 [29] A deep convolutional neural network-based approach for detecting burn severity from skin burn images | Bangladesh | Experimental study | VGG16 | 1530 | 1071 images | Accuracy = 95.80% Recall = 95.00% Precision = 96.00% DC = 95.00% |

| Pabitha et al. 2021 [20] Densemask RCNN: A Hybrid Model for Skin Burn Image Classification and Severity Grading | India | Comparative study | DenseMask RCNN | 1800 | 1200 | Accuracy = 86.63% Precision = 85.00% Recall = 89.00% DC = 86.90% |

| Abubakar et al. 2020 [30] Assessment of Human Skin Burns: A Deep Transfer Learning Approach | UK, Nigeria | Experimental study | ResNet50 | 1360 UK cohort + 540 Nigerian cohort | 1520 | Accuracy = 97.10% using the Nigerian dataset Accuracy = 99.30% using the Caucasian dataset |

| Pabitha et al. 2024 [21] Dense Mesh RCNN: assessment of human skin burn and burn depth severity | India | Comparative study | Dense Mesh RCNN | 1150 | 1000 | Accuracy = 94.10% Precision 95.90% Recall = 94.80% DC = 95.30% |

| Khan et al. 2020 [31] Computer-aided diagnosis for burnt skin images using deep convolutional neural network | Pakistan | Experimental study | CNN modified with more layers to DCNN | 450 | 293 | Accuracy = 79.40% |

| Abubakar et al. 2020 [32] Burns Depth Assessment Using Deep Learning Features | UK, Nigeria | Comparative study | ResFeat50, VggFeat16 | 2080 | 520 LDPI images | ResFeat50 Accuracy = 95.43% Precision = 95.50% Recall = 95.50% DC = 95.50% VGGFeat16 Accuracy = 85.67% Precision = 86.25% Recall = 85.75% DC = 85.75% |

| Yadav et al. 2022 [33] Human burn depth and grafting prognosis using ResNeXt topology based deep learning network | India | Experimental study | ResNeXt modified to BNeXt | 94 expanded to 6000 | 4800 | Accuracy = 97.17% Recall = 97.25% Precision = 97.20% DC = 97.22% |

| Yadav et al. 2023 [34] Spatial attention-based residual network for human burn identification and classification | India | Experimental study | ResNeXt modified to BuRnGANeXt50 | 94 expanded to 6000 | 4800 | Accuracy = 98.14% Recall = 97.22% Precision = 97.22% DC = 97.22% |

| Author/Title/Year | Country | Study Design | AI Model | Data Set (# Images) | Training Set (# Images) | Outcome | Summary Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2020 [35] Real-time burn depth assessment using artificial networks: a large-scale, multicentre study. | China | Experimental study | ResNet50 | 484 expanded to 5637 images | 3945 | Healing time Shallow (0–10 days), moderate (11–20 days), deep more than 21 days or wound healing by surgical skin graft | Recall = 82.34% Precision = 82.67% F1 score = 82% |

| Ethier et al. 2024 [22] Using Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence to Track the Healing of Severe Burns. | Canada | Experimental study | Skin abnormality tracking algorithm that uses BAM | 1559 | 1285 | Healing Time By tracking 4 colours of the wound | F1 Score 82% |

| Boissin et al. 2023 [17] Development and evaluation of deep learning algorithms for assessment of acute burns and the need for surgery. | Sweden, South Africa | Experimental study | Aiforia Create self-service deep learning tool | 1105 + 536 background images | 773 | Surgical vs. non-surgical | Recall = 92.5% Specificity = 53.6% AUC = 88.5% |

| Yadav 2022 [33] Human burn depth and grafting prognosis using ResNeXt topology based deep learning network | India | Experimental study | Modified version of ResNeXt to BNeXt | 94 expanded to 6000 | 4800 | Graft vs. non-graft | Accuracy = 99.67% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Holm, S.; Huss, F.; Nayyer, B.; Zdolsek, J. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Burn Assessment: A Scoping Review with a Large Language Model-Generated Decision Tree. Eur. Burn J. 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010004

Holm S, Huss F, Nayyer B, Zdolsek J. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Burn Assessment: A Scoping Review with a Large Language Model-Generated Decision Tree. European Burn Journal. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolm, Sebastian, Fredrik Huss, Bahaman Nayyer, and Johann Zdolsek. 2026. "Use of Artificial Intelligence in Burn Assessment: A Scoping Review with a Large Language Model-Generated Decision Tree" European Burn Journal 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010004

APA StyleHolm, S., Huss, F., Nayyer, B., & Zdolsek, J. (2026). Use of Artificial Intelligence in Burn Assessment: A Scoping Review with a Large Language Model-Generated Decision Tree. European Burn Journal, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010004