Exploring Ethnic Disparities in Burn Injury Outcomes in the UK: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Searches

2.2. Study Selection Criteria

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction & Analysis

2.5. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

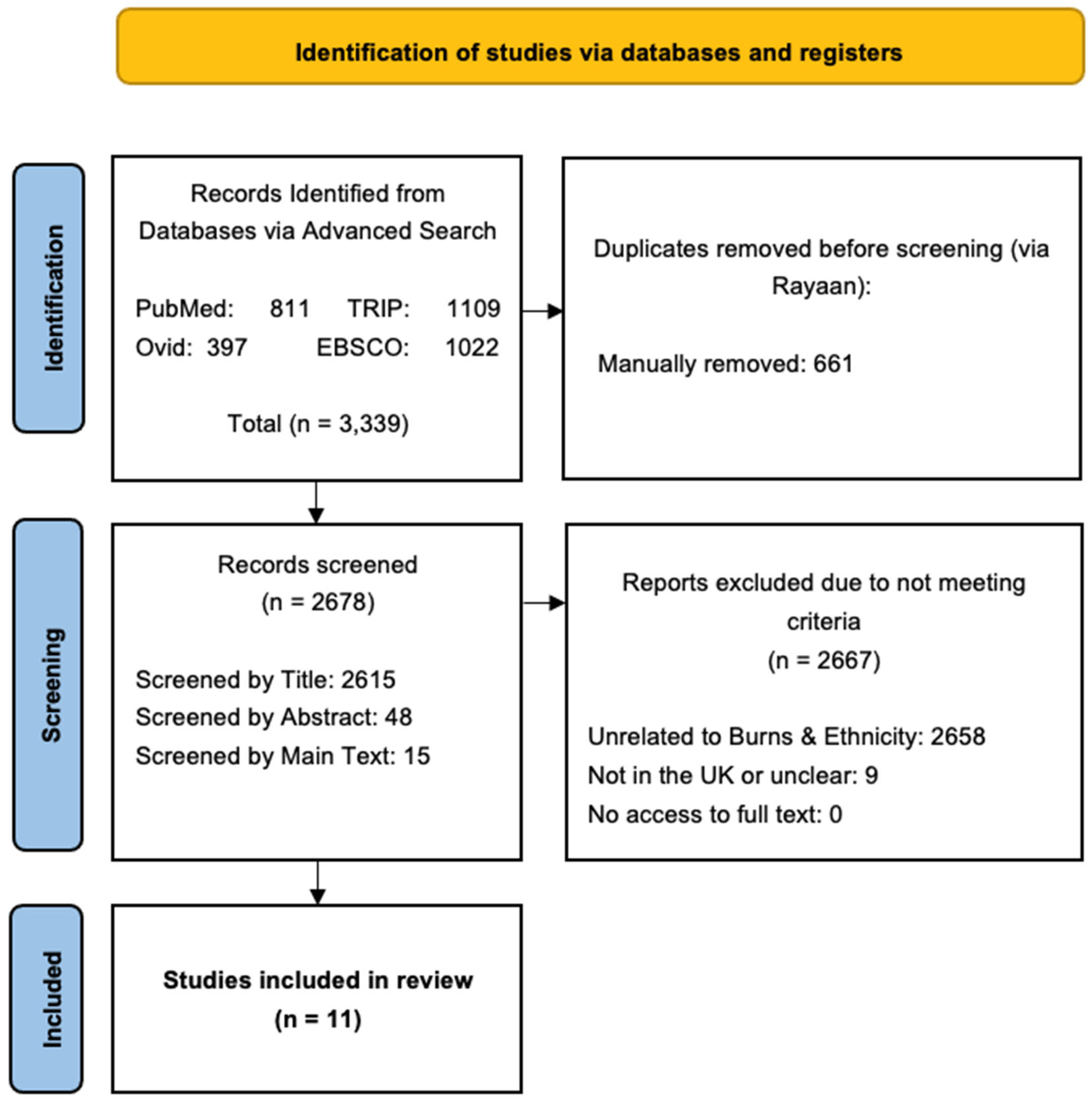

3.1. Identification of Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Cause of Burns

3.2.2. Type & Extent of Burns

3.2.3. Proportion of Burns

3.2.4. Location of Burn Incidents

3.2.5. First Aid Before Admission

3.2.6. Length of Stay in Hospital

3.2.7. Outcomes Following Admission

4. Discussion

4.1. Culturally Appropriate Prevention

4.2. Improving Equity and Outcomes

4.3. Future Challenges

4.4. Risk of Bias

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| TBSA | Total Body Surface Area |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| IMD | Index of Mass Deprivation |

| SIR | Standardised Incidence Ratios |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

References

- Warby, R.; Maani, C.V. Burn classification. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539773/ (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Kelly, D.; Johnson, C. Management of burns. Surgery 2021, 39, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. CKS for Burns and Scalds: Background information—Prevalence; NICE: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/burns-scalds/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Kalson, N.S.; Jenks, T.; Woodford, M.; Lecky, F.E.; Dunn, K.W. Burns represent a significant proportion of the total serious trauma workload in England and Wales. Burns 2012, 38, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. CKS Is Burns and Scalds: Diagnosis—Assessment; NICE: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/burns-scalds/diagnosis/assessment/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Pellatt, R.A.F.; Williams, A.; Wright, H.; Young, A.E.R. The cost of a major paediatric burn. Burns 2010, 36, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.F.; Rodríguez-Mercedes, S.L.; Grant, G.G.; Rencken, C.A.; Kinney, E.M.; Austen, A.; Brady, K.J.S.; Schneider, J.C.; Kazis, L.E.; Ryan, C.M.; et al. Physical, psychological, and social outcomes in pediatric burn survivors ages 5 to 18 years: A systematic review. J. Burn Care Res. 2022, 43, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelling, S.; Challoner, T.; Lewis, D. Burns and socioeconomic deprivation: The experience of an adult burns centre. Burns 2021, 47, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, V. The Health of People from Ethnic Minority Groups in England [Internet]; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/health-people-ethnic-minority-groups-england (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Ikpeme, M.; Emond, A.; Mytton, J.; Hollen, L. Ethnic inequalities in paediatric burns: Findings from a systematic review and analyses of hospital episodes statistics data from 2009 to 2015. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, A59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burns [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Morgner, C.; Patel, H. Understanding ethnicity and residential fires from the perspective of cultural values and practices: A case study of Leicester, United Kingdom. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 125, 103384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzopoulos, P.; Zarogoulidis, P.; Mitrakas, A.; Karanikas, M.; Milothridis, P.; Matthaios, D.; Kouroumichakis, I.; Proikaki, S.; Pavlioglou, P.; Katsikogiannis, N.; et al. Occupational chemical burns: A 2-year experience in the emergency department. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2011, 4, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shamsi, H.; Almutairi, A.G.; Al Mashrafi, S.; Al Kalbani, T. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: A systematic review. Oman Med. J. 2020, 35, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Bello, M.S.; Spera, L.; Gillenwater, T.J.; Yenikomshian, H.A. The impact of race/ethnicity on the outcomes of burn patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Burn Care Res. 2021, 43, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Ethnic Category [Internet]; Data Dictionary NHS: UK. 2024. Available online: https://www.datadictionary.nhs.uk/data_elements/ethnic_category.html (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121 Pt 1, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programme CASP. CASP Qualitative Checklist [Internet]; CASP: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Alnababtah, K.M.; Davies, P.; Jackson, C.A.; Ashford, R.L.; Filby, M. Burn injuries among children from a region-wide paediatric burns unit. Br. J. Nurs. 2011, 20, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnababtah, K.M.; Khan, S. Socio-demographic factors which significantly relate to the prediction of burns severity in children. Int. J. Burn Trauma 2017, 7, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H.E.; Bache, S.E.; Muthayya, P.; Baker, J.; Ralston, D.R. Are parents in the UK equipped to provide adequate burns first aid? Burns 2012, 38, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, H.; Kokocinska, M.; Lewis, D. A five year review paediatric burns social deprivation: Is there a link? Burns 2017, 43, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.T.; Prowse, P.M.; Falder, S. Ethnic differences in burn mechanism and severity in a UK paediatric population. Burns 2012, 38, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipulendran, V.; Lawrence, J.C.; Sunderland, R. Ethnic differences in incidence of severe burns and scalds to children in Birmingham. BMJ 1989, 298, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, C.T.; Coyle, B.; Varma, S. Trends in hospital admissions for burns in England, 1991–2010: A descriptive population-based study. Burns 2013, 39, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, J.S.; Atkins, J.; Clancy, O.; Takata, M.; Dunn, K.W.; Jones, I.; Vizcaychipi, M.P. Geographical analysis of socioeconomic factors in risk of domestic burn injury in London 2007–2013. Burns 2015, 41, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, J.M.; Khan, A.A.; Shenton, A.F.; Sharpe, D.T. Burn patterns of Asian ethnic minorities living in West Yorkshire, UK. Burns 2006, 32, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, L.; Hari, I.; Bamford, L. Associations between ethnicity and referrals, access, and engagement in a UK adult burns clinical psychology service. Eur. Burn J. 2023, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Rawlins, J.; Shenton, A.F.; Sharpe, D.T. The Bradford Burn Study: The epidemiology of burns presenting to an inner city emergency department. Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NWC. Blank Map of United Kingdom (UK): Outline Map and Vector Map of United Kingdom (UK) [Internet]. Available online: https://ukmap360.com/united-kingdom-%28uk%29-blank-map (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Ethnic Group, England and Wales: Census 2021 [Internet]; ONS: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Peck, M.D. Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: Distribution and risk factors. Burns 2011, 37, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, Z.J.; McCool, K.; Magee, W.P.I.I.I.; Potokar, T.; Gillenwater, J. Burn injuries in Asia: A global burden of disease study. J. Burn Care Res. 2022, 43 (Suppl. 1), S40–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, N.; Buchan, I.; Dunn, K. A review of the international burn injury database (iBID) for England and Wales: Descriptive analysis of burn injuries 2003–2011. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e006184corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Age UK. Gas and Fire Home Safety for Elderly People [Internet]; Age UK: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/information-advice/care/housing-options/home-safety/fire-prevention-gas-safety-and-electric-safety (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Legislation.gov.uk. The Building Regulations 2010 [Internet]. 2010. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/2214/contents (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Apps, P. Survivors’ Lawyers Call for “Racial Discrimination” to be Considered as Factor in Grenfell Fire [Internet]; Inside Housing: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/survivors-lawyers-call-for-racial-discrimination-to-be-considered-as-factor-in-grenfell-fire-67075 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Rudder, A. Food safety and the risk assessment of ethnic minority food retail businesses. Food Control 2006, 17, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Action Sustainability. Diversity Survey Benchmarking Report 2023 [Internet]; Action Sustainability: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.actionsustainability.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/240116_Diversity-Survey-Benchmarking-Report_IG.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Government Digital Service. Fire Safety in the Workplace [Internet]. 2012. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/workplace-fire-safety-your-responsibilities/fire-risk-assessments (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Fire Safety Act index [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Fire_Safety_Act_index (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Nagarajan, M.; Mohamed, S.; Asmar, O.; Stubbington, Y.; George, S.; Shokrollahi, K. Data from national media reports of ‘acid attacks’ in England: A new piece in the jigsaw. Burns 2020, 46, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.F.; Fuller, G.W.; Edwards, J. Cohort study evaluating management of burns in the community in clinical practice in the UK: Costs and outcomes. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorks, M. Burns—Regional Burns Service [Internet]; Mid Yorks: West Yorkshire, UK. Available online: https://www.midyorks.nhs.uk/burns/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Wise, J. Racial health inequality is stark and requires concerted action, says review. BMJ 2022, 376, o382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, A.; Negussie, Y.; Geller, A.; Weinstein, J.N. The Root Causes of Health Inequity [Internet]; National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Marmot, M. Health equity in England: The Marmot review in 10 years on. BMJ 2020, 368, m693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, A.; Taylor, K.; Mohebati, L.M.; Sundin, J.; Cooper, M.; Scanlon, T.; de Visser, R. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: A qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henley, P.; Martins, T.; Zamani, R. Assessing ethnic minority representation in fibromyalgia clinical trials: A systematic review of recruitment demographics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S., Jr.; Lara, P.N.; Dang, J.H.; Paterniti, D.A.; Kelly, K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): Laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: Renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer 2014, 120, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, A. Flawed NHS records skew ethnic health data, says study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Ethnicity [Internet]; NHS Digital: West Yorkshire, UK, 2022; Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-collections-and-data-sets/data-sets/mental-health-services-data-set/submit-data/data-quality-of-protected-characteristics-and-other-vulnerable-groups/ethnicity (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- DiPaolo, N.; Hulsebos, I.F.; Yu, J.; Gillenwater, T.J.; Yenikomshian, H.A. Race and ethnicity influence outcomes of adult burn patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2023, 44, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.; Higgins, D.L. Housing and health: Time again for public health action. Am. J. Public. Health. 2002, 92, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. First Aid in Schools, Early Years and Further Education [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/first-aid-in-schools/first-aid-in-schools-early-years-and-further-education (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Alison, J. SCOTS—Burns in School [Internet]. Available online: https://www.scottishcorpus.ac.uk/document/?documentid=962 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- General Medical Council. Medical Education Projects [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula#medical-education-projects (accessed on 19 October 2024).

| Author | Title | Study Aims | * Methodology | Timeline | * Sample Size, Age & Gender | Ethnicity | * Cause of Burn | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that discussed Ethnic Disparities in Infants, Children and Young Adults | ||||||||

| Alnababtah et al., 2011 [20] | Burn injuries among children from a region-wide paediatric burns unit | Patterns in age, gender, ethnicity, IMD, season, time, cause and severity of burns (TBSA), alongside length of hospital stay |

| 2004–2008 |

| White: 787 (63) Asian: 353 (28) African: 75 (6) Mixed: 34 (3) |

| The primary source of burns were spills (765 cases; 61%) and contact injuries (150 cases; 12%). Asian British children exhibited higher rates of admission for burns and were significantly younger at the time (p < 0.05). |

| Alnababtah and Khan 2017 [21] | Socio-demographic factors which significantly relate to the prediction of burns severity in children | Relationship between age, gender, ethnicity and the incidence and mechanisms of burn injuries |

| 2011–2012 |

| White British: 78 (49) Asian British: 40 (25) African British: 15 (9) Other: 12 (8) Afro-Caribbean: 10 (6) Mixed: 5 (3) |

| Burn injuries were significantly higher in children ≤ 5 years old (p < 0.001) and male children (58.1%). Burns were more frequent in minority ethnic groups (p < 0.001); younger aged parents ≤ 25 years old (p = 0.048); and children living with single parents (p = 0.001). Most burns cases resulted from spills (74.4%) and during mealtimes (p < 0.001). |

| Graham et al., 2012 [22] | Are parents in the UK equipped to provide adequate burns first aid? | Differences in first aid practice for burns, including duration of running cool water, seeking medical attention or use of cling film or inappropriate remedies by demographic |

| 2009 |

| White: 152 (81) Other: 36 (19) |

| White British parents were significantly more likely to administer appropriate first aid using cool water compared to other ethnic groups (p = 0.05). 92% (n = 173) of all parents reported using appropriate dressings to protect the wound, 26% (n = 9) of parents from minority ethnic backgrounds indicated the use of potentially harmful remedies. |

| Richards et al., 2017 [23] | A five-year review of paediatric burns and social deprivation: Is there a link? | Associations between age, gender, ethnicity IMD, mechanism of burn and incidence, alongside first aid practices |

| 2006–2011 |

| White: 760 (45) Asian: 456 (27) African: 169 (10) Unknown: 303 (18) |

| The most common mechanism of injury was scalding (61%) and there was a male preponderance (58%). The most affected age group were 1–2-year-olds (38%). Children from Asian and African descent were over-represented in hospital admissions for burn injuries (p = 0.0065). |

| Tan et al., 2012 [24] | Ethnic differences in burn mechanism and severity in a UK paediatric population | Differences in age, gender, ethnicity, IMD cause and location of burn, severity and mechanism of burn and length of hospital stay |

| 2005–2010 |

| White: 692 (90) Asian: 19 (3) Other: 18 (2) Chinese: 16 (2) Black: 13 (2) Mixed: 8 (1) |

| Ethnic minority children sustained burns with a significantly higher total body surface area (p < 0.001) and experienced longer hospital stays (p < 0.001) compared to non-ethnic minority children and ethnic minority children were found to be more socioeconomically deprived than their non-ethnic minority counterparts (p = 0.02). |

| Vipulendran et al., 1989 [25] | Ethnic differences in incidence of severe burns and scalds to children in Birmingham | The incidence of burns by age, gender, ethnicity, TBSA |

| 1983–1987 |

| Non-Asian °: 445 (74) Asian: 155 (26) |

| A disproportionate number of Asian children were admitted for burn injuries in Birmingham compared to their non-Asian counterparts (OR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.29–1.8) |

| Studies that discussed Ethnic Disparities in Adults (and Infants to Children) | ||||||||

| Brewster et al., 2013 [26] | Trends in hospital admissions for burns in England, 1991–2010 | Associations between sex, age, ethnicity, IMD quintile and burns |

| 2001–2010 |

| N/S |

| Rates of hospital admissions for burn injuries in England were higher in most ethnic minority groups, compared to White British population. |

| Heng et al., 2015 [27] | Geographical analysis of socioeconomic factors in risk of domestic burn injury in London 2007–2013 | Risk of burn with age, gender, ethnicity, IMD, health deprivation and disability score, household density and barriers to housing |

| 2007–2013 |

| N/S |

| The relative risk of paediatric domestic burn injury was independently associated with percentage of ethnic minorities (p = 0.005), income deprivation (p < 0.001), health deprivation and disability (p = 0.031) and percentage of families with ≥3 children (p = 0.004). |

| Rawlins et al., 2006 ‡ [28] | Burn patterns of Asian ethnic minorities living in West Yorkshire, UK | Patterns in age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, cause and type of burn, burn location, first-aid, extent of burn, pre-hospital analgesia and outcomes |

| 2003–2004 |

| White: 263 (57) Asian: 188 (41) Black: 9 (2) |

| In the Asian ethnic minority group, 37% of contact burns were caused by hot irons, and 11% of patients used inappropriate remedies such as butter and toothpaste. There were no significant differences in burn severity or mortality compared to non-Asian patients. |

| Shepherd et al., 2023 [29] | Associations between Ethnicity and Referrals, Access and Engagement in a UK Adult Burns Clinical Psychology Service | Access & engagement with burns clinical psychology in respect to age, gender, ethnicity |

| 2014–2022 |

| White: 471 (67) Asian: 43 (6) Other White: 38 (5) Black: 28 (4) Mixed: 10 (1) Other: 9 (1) Unknown: 100 (14) |

| White British patients (p < 0.001) were less likely to be referred to the burns clinical psychology service, whereas patients within Black (p < 0.001) and Asian (p < 0.001) ethnic groups were more likely to be referred. |

| Khan et al., 2007 ‡ [30] | The Bradford Burn Study: the epidemiology of burns presenting to an inner-city emergency department | Relationship between age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, cause and type of burn, alongside burn location, monthly variations, severity, and outcomes, with the use of pre-hospital analgesia in burn patients |

| 2003–2004 |

| White: 263 (57) Asian: 188 (41) Black: 9 (2) |

| Although individuals of Asian origin represent only 10.0% of the population, they accounted for 40.8% of burn injuries, in contrast to 57.1% among White patients. Most cases (85%) were accidental, with scalds representing the most common injury type at 52%. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badakhshan, U.; Zamani, R.; Martins, T. Exploring Ethnic Disparities in Burn Injury Outcomes in the UK: A Systematic Review. Eur. Burn J. 2025, 6, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030048

Badakhshan U, Zamani R, Martins T. Exploring Ethnic Disparities in Burn Injury Outcomes in the UK: A Systematic Review. European Burn Journal. 2025; 6(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadakhshan, Uashar, Reza Zamani, and Tanimola Martins. 2025. "Exploring Ethnic Disparities in Burn Injury Outcomes in the UK: A Systematic Review" European Burn Journal 6, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030048

APA StyleBadakhshan, U., Zamani, R., & Martins, T. (2025). Exploring Ethnic Disparities in Burn Injury Outcomes in the UK: A Systematic Review. European Burn Journal, 6(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030048