Interventions for Functional and Cosmetic Outcomes Post Burn for Eyelid Ectropion—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search

2.5. Selection of Sources

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Data Items

2.8. Levels of Evidence

2.9. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

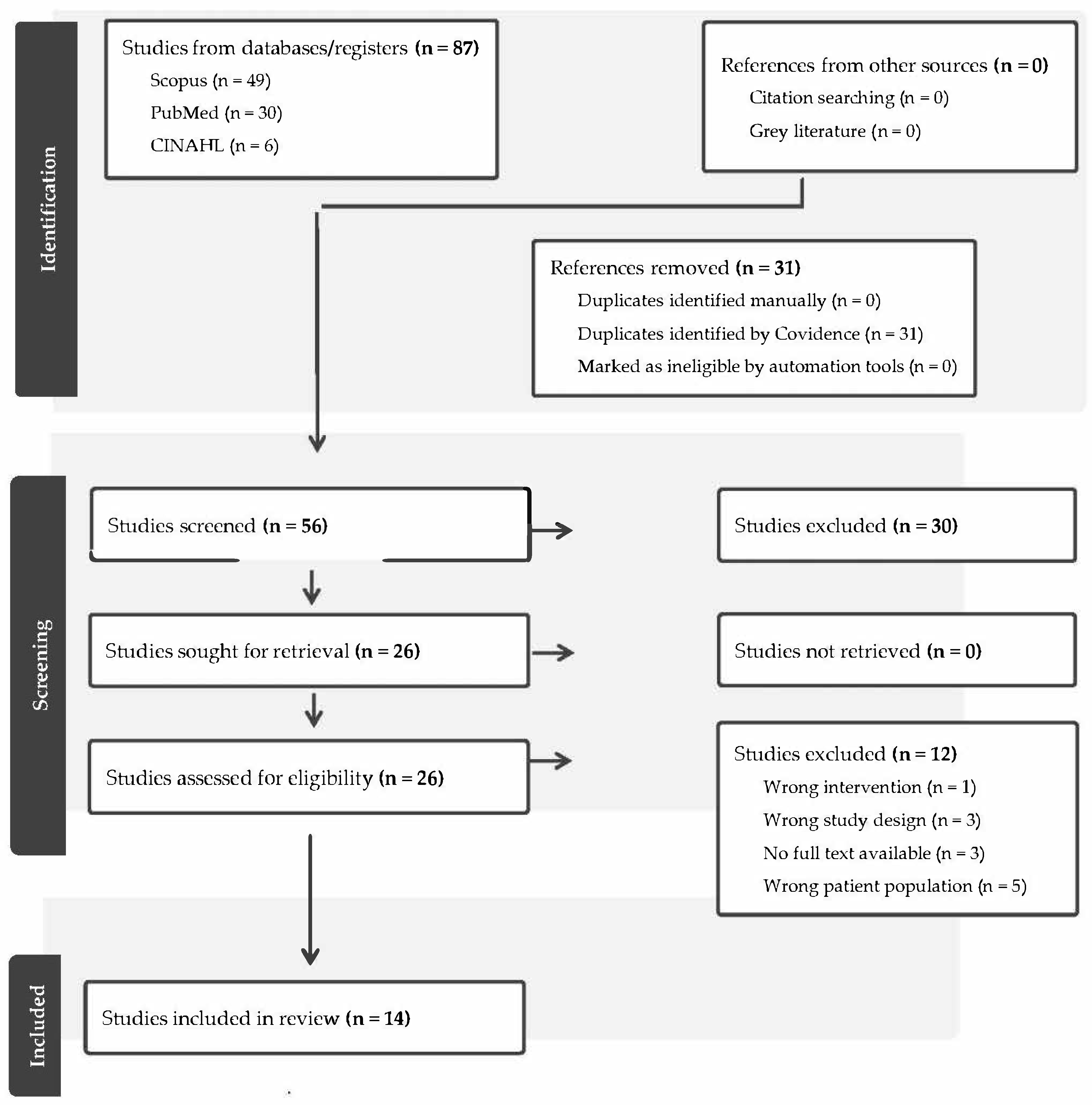

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

3.3. Critical Appraisal Within Sources of Evidence

3.4. Synthesis of Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. PRISMA-ScR Checklist

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 4 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 5 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 5, 6 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 6 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 6 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 7 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 7 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 47 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | 8 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 8 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 8 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 10 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | 10 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 11–15, 17–28 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 16 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 29 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 32 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 32, 33 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 34 |

Appendix A.2. Search Strategy

| Database Search Conducted on 12 August 2024 | Search Search Strategy Includes Concepts and Limits: (Eyelid) AND (Ectropion) AND (Burn) | Search Result (n) With Date Limit: Scope of Search was Refined to 2014–2024 for Each of the Databases Searched |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed search, includes MeSH | (“Ectropion”[Mesh] OR “ectropion”[tiab] OR “ectropions”[tiab]) AND (“Eyelids”[Mesh] OR “eyelids”[tiab] OR “eyelid”[tiab]) AND (“Burns”[Mesh] OR “Eye Burns”[Mesh] OR “Burn Units”[Mesh] OR “burn”[tiab] OR “burns”[tiab] OR “postburn”[tiab] OR “postburns”[tiab] OR “post-burn”[tiab] OR “post-burns”[tiab]) | 30 |

| Embase, includes Emtree | (‘ectropion’/exp “ectropion”:ti,ab OR “ectropions”:ti,ab) AND (‘eyelid’/exp OR “eyelids”:ti,ab OR “eyelid”:ti,ab) AND (‘burn’/exp OR ‘eye burn’/exp OR ‘burn unit’/exp OR “burn”:ti,ab OR “burns”:ti,ab OR “postburn”:ti,ab OR “postburns”:ti,ab OR “post-burn”:ti,ab OR “post-burns”:ti,ab) | 40 |

| CINAHL Complete, includes CINAHL Subject Headings | (TI(“ectropion” OR “ectropions”) OR AB(“ectropion” OR “ectropions”)) AND (MH “Eyelids+” OR TI(“eyelids” OR “eyelid”) OR AB(“eyelids” OR “eyelid”)) AND (MH “Burns+” OR MH “Burn Units” OR MH “Burn Patients” OR TI(“burn” OR “burns” OR “postburn” OR “postburns” OR “post-burn” OR “post-burns”) OR AB(“burn” OR “burns” OR “postburn” OR “postburns” OR “post-burn” OR “post-burns”)) | 6 |

| Cochrane Library, includes MeSH | ID Search Hits #1 MeSH descriptor: [Ectropion] explode all trees 14 #2 (“ectropion” OR “ectropions”):ti,ab,kw 97 #3 #1 OR #2 97 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Eyelids] explode all trees 1409 #5 (“eyelids” OR “eyelid”):ti,ab,kw 2638 #6 #4 OR #5 3535 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Burns] explode all trees 2439 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Eye Burns] explode all trees 33 #9 MeSH descriptor: [Burn Units] explode all trees 55 #10 (“burn” OR “burns” OR “postburn” OR “postburns” OR “post-burn” OR “post-burns”):ti,ab,kw 6605 #11 #8 OR #9 OR #10 6605 #12 #3 AND #6 AND #11 1 | 1 |

| SCOPUS search, includes phrase searching and field searching: | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“Ectropion” OR “ectropion” OR “ectropions”) AND (“Eyelids” OR “eyelids” OR “eyelid”) AND (“Burns” OR “Eye Burns” OR “Burn Units” OR “burn” OR “burns” OR “postburn” OR “postburns” OR “post-burn” OR “post-burns”)) | 49 |

References

- Hoogewerf, C.J.; van Baar, M.E.; Middelkoop, E.; van Loey, N.E. Impact of facial burns: Relationship between depressive symptoms, self-esteem and scar severity. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, K.E.; Thomas, J.R. The Changing Face of Beauty: A Global Assessment of Facial Beauty. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 53, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Cox, R. Recognizing human faces. Appl. Ergon. 1975, 6, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, I.; Legemate, C.M.; Dokter, J.; Van Loey, N.E.; van Baar, M.E.; Polinder, S. Predictors of health-related quality of life after burn injuries: A systematic review. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelan, M.B.; Bojovic, B. Reconstruction of the head and neck after burns. In Total Burn Care; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 532–554.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Bouguila, J.; Viard, R.; Brun, A.; Voulliaume, D.; Comparin, J.; Foyatier, J. Management of eyelid burns. J. Fr. D’ophtalmologie 2011, 34, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, K.D.; Bineshfar, N.; Walsh, H.L.; Johnson, T.E. Burn-Induced Cicatricial Eyelid Retraction: A Challenging Case and Review of Management Principles. J. Burn Care Res. 2024, 45, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, E.F.; Frew, Q.; Din, A.; Pleat, J.; Ashraff, S.; Ghazi-Nouri, S.; El-Muttardi, N.; Philp, B.; Dziewulski, P. Periorbital burns–a 6 year review of management and outcome. Burns 2015, 41, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, R.; Sheikh, I.; Dheansa, B. The management of eyelid burns. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2009, 54, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, N.; Ward, E.; Maitz, P. Full thickness facial burns: Outcomes following orofacial rehabilitation. Burns 2015, 41, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serghiou, M.A.; Ott, S.; Whitehead, C.; Cowan, A.; McEntire, S.; Suman, O.E. Comprehensive rehabilitation of the burn patient. In Total Burn Care: Fourth Edition; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 517–549.e4. [Google Scholar]

- Passaretti, D.; Billmire, D.A. Management of pediatric burns. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2003, 14, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. JBI Levels of Evidence. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI-Levels-of-evidence_2014_0.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Clayton, N.A.; Haertsch, P.A.; Maitz, P.K.; Issler-Fisher, A.C. Ablative Fractional Resurfacing in Acute Care Management of Facial Burns: A New Approach to Minimize the Need for Acute Surgical Reconstruction. J. Burn Care Res. 2019, 40, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilani, C.; De Faria, A.; Baus, A.; Delbarre, M.; Schaal, J.V.; Froussart-Maille, F.; Bey, E.; Duhamel, P. Eyelid Chemical Burns: A Multidisciplinary And Challenging Approach. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters 2021, 34, 312–318. [Google Scholar]

- Elbanoby, T.M.; Elbatawy, A.; Aly, G.M.; Ayad, W.; Helmy, Y.; Helmy, E.; Sholkamy, K.; Dahshan, H.; Al-Hady, A. Bifurcated Superficial Temporal Artery Island Flap for the Reconstruction of a Periorbital Burn: An Innovation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Hou, C.; Zhang, J. Combining the Tunnel Orbicularis Oculi Muscle Flap Technique With Skin Grafting for Enhanced Adhesion in Burn-Induced Ectropion Repair. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 40, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, T.; Alessandri-Bonetti, M.; Liu, H.; Pandya, S.; Stofman, G.M.; Egro, F.M. Fourteen-Year Experience in Burn Eyelid Reconstruction and Complications Recurrence: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2024, 92 (Suppl. 2), S146–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, N.; Dizdarevic, A.; Dizdarevic, N.; Haracic, A.; Gafurovic, L. Case report of Wolfe grafting for the management of bilateral cicatricial eyelid ectropion following severe burn injuries. Ann. Med. Surg. 2018, 34, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.W.; Levitt, A.E.; Erickson, B.P.; Ko, A.C.; Nikpoor, N.; Ezuddin, N.; Lee, W.W. Ablative Fractional Laser Resurfacing With Laser-Assisted Delivery of 5-Fluorouracil for the Treatment of Cicatricial Ectropion and Periocular Scarring. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 34, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lymperopoulos, N.S.; Jordan, D.J.; Jeevan, R.; Shokrollahi, K. A lateral tarsorrhaphy with forehead hitch to pre-empt and treat burns ectropion with a contextual review of burns ectropion management. Scars Burns Health 2016, 2, 2059513116642081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, S.; Nikolaidou, E.; Joycey, A.P.; Tzimorota, Z.; Karagergou, E. Reconstruction of Bilateral Upper and Lower Eyelid Ectropion Caused by a Liquid Unblocker Chemical Burn. Cureus 2023, 15, e40880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K.; Sakai, S.; Kishi, K. Treatment of Cicatricial Lower Eyelid Ectropion with Suture of Horner Muscle Combined with Fascia Transplantation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vana, L.P.; Isaac, C.; Alonso, N. Treatment of extrinsic ectropion on burned face with facial suspension technique. Burns 2014, 40, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşiloğlu, N.; Şirinoğlu, H.; Sarıcı, M.; Temiz, G.; Güvercin, E. A simple method for the treatment of cicatricial ectropion and eyelid contraction in patients with periocular burn: Vertical V-Y advancement of the eyelid. Burns 2014, 40, 1820–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucal, I.; Waldner, M.; Shojaati, G.; Schweizer, R.; Klein, H.J.; Giovanoli, P.; Plock, J.A. Burn Scar Ectropion Correction: Surgical Technique for Functional Outcomes. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 88, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.; Chung, J.H.; Yoon, E.S.; Lee, B.I.; Park, S.H. Algorithm for the management of ectropion through medial and lateral canthopexy. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2018, 45, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauley, J.; Schnake, E.; Smith, T.; Lambert Wagner, A.; Wiktor, A. 496 treatment of lagophthalmos using kinesiology tape in burn patients: A case study. J. Burn Care Res. 2018, 39 (Suppl. 1), S220–S221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalag, M.S.; Wasiak, J.; Syed, Q.; Paul, E.; Hall, A.J.; Cleland, H. Risk factors for ocular burn injuries requiring surgery. J. Burn Care Res. 2017, 38, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, T.; Wynn, R. The clinical case report: A review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Age 18 years or older Burn injury/injuries to face including eye(s) Facial burn ≥ superficial partial thickness Involving treatment/intervention for eyelid ectropion Conducted in acute hospital or outpatient department setting | Age younger than 18 years Pre-existing eye conditions impacting function or cosmetic appearance Participants presenting greater than 18 months post burn injury |

| Study | JBI Level | Study Design | Aim | Sample * (n = Eyes) | Aim of Intervention for Ectropion | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clauss, Bineshfar [7] 2024 USA | 4 | Retrospective review | To describe a complex and challenging patient with cicatricial eyelid ectropion and discuss the management principles for eye exposure keratopathy and eyelid retraction therapy. | n = 2 | Management | Surgical |

| Clayton, Haertsch [16] 2019 Australia | 4 | Retrospective single-centre case study | To evaluate the efficacy of ablative fractional CO2 laser intervention early in the acute treatment of panfacial burn injury. | n = 2 | Prevention & Management | Surgical & non-surgical |

| Elbanoby, Elbatawy [18] 2016 Egypt | 4 | Case series | To present a single pertinent solution to address all problems in the periorbital area. | n = 14 | Management | Surgical |

| Hou, Hou [19] 2024 China | 4 | Case series | To retrospectively examine upper and lower eyelid adhesions using an orbicularis oculi muscle flap and verify its stability. | n = 46 | Management | Surgical |

| Jeong, Alessandri-Bonetti [20] 2024 USA | 4 | Case series | To describe the complication rates in burn eyelid reconstruction at a single centre for 14 years. | n = 23 | Management | Surgical |

| Jovanovic, Dizdarevic [21] 2018 Bosnia and Herzegovina | 4 | Case report | To present a case of bilateral cicatricial eyelid ectropion management following severe burn injuries in a patient who previously sustained severe, deep dermal thermal injuries. | n = 2 | Management | Surgical |

| Keilani, De Faria [17] 2021 France | 4 | Case study | To present the case of a woman who presented second- and third-degree burns of the eyelids secondary to physical domestic assault with acid, who had early surgical management with a full-thickness skin graft. | n = 2 | Prevention & Management | Surgical |

| Lee, Levitt [22] 2018 USA | 4 | Case report | To report on the efficacy and safety of a novel nonsurgical approach to treating cicatricial ectropion using ablative fractional laser resurfacing and laser-assisted delivery of 5-fluorouracil. | n = 1 | Management | Surgical |

| Lymperopoulos, Jordan [23] 2016 UK | 4 | Case report | To describe our early experience of a novel technique for temporary lateral tarsorrhaphy with forehead hitch, which protects the globe and counters the scar- and gravity-related ectropic effects on the lower eyelids. | n = 2 | Management | Surgical |

| Papadopoulou, Nikolaidou [24] 2023 Greece | 4 | Case report | To stress the need for preventive measures regarding the use of chemicals and for close observation and timely surgical intervention in chemical burn patients to prevent and limit disfigurement. | n = 2 | Management | Surgical |

| Takaya, Sakai [25] 2024 Japan | 4 | Retrospective cohort study | To describe a new technique for correcting contractures and deformities that reliably addresses lacrimal punctum deviation and severe cicatricial lower eyelid ectropion. | n = 1 | Management | Surgical |

| Vana, Isaac [26] 2014 Brazil | 4 | Retrospective analysis | To evaluate the outcome of 8 extrinsic ectropion’s secondary to facial burns treated with facial suspension technique. | n = 3 | Management | Surgical |

| Yeşiloğlu, Şirinoğlu [27] 2014 Turkey | 4 | Retrospective case series | To present a simple but useful technique involving the V-Y advancement of the eyelid or eyelids in the vertical direction for the prevention of cicatricial ectropion and eyelid contraction. | n = 1 | Management | Surgical |

| Zucal, Waldner [28] 2022 Switzerland | 4 | Case report | To present our surgical technique for lateral canthopexy in combination with full-thickness skin grafting in patients with eyelid axis distortion after scar contraction of the periorbital region after severe burn injuries of the face. | n = 10 | Management | Surgical |

| Study | Participants | Sample (n = Eyes) | Intervention | Outcome Measures | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clauss, Bineshfar [7] 2024 | 1 patient, 43 years old with 50% TBSA burns including scalp and facial burn | n = 2 | Initial management: multiple procedures including ReCell and Meek micrografting. 42 days post injury: Partial-thickness autologous skin grafting—integra grafts. Post-operative day 8: Bilateral Gunderson Flaps and Synthetic Skin Substitute for Anterior Lamellae Lengthening, and Bilateral permanent Tarsorrhaphies. 42 days post-surgery: repeat Repair for Recurrent Retraction with Autologous Free FTSG *. | Ectropion recurrence; Lagophthalmos; Eyelid function/competence; Exposure keratopathy. | Post surgery 1: Ectropion recurrence—yes Lagophthalmos—present Eyelid function—incompetent Exposure keratopathy—present, bilateral corneal ulcers. Post surgery 2: Ectropion recurrence—yes Post surgery 3: Ectropion recurrence—nil Lagophthalmos—nil Eyelid function—competent Exposure keratopathy—nil |

| Clayton, Haertsch [16] 2019 | 1 patient, 39 years old with 68% TBSA burns including facial burn | n = 2 | Initial management: Blunt debridement and Biobrane xenograft applied to burns. From 48 h post injury: Nonsurgical orofacial scar contracture management: AROM exercises, stretching, mouth splint, topical lubricant applied frequently for corneal protection. 42 days post injury: Ablative fractional CO2 laser and non-surgical scar contracture management. 4x sessions over 8 months, 6- to 8-week intervals. 133 days post injury: Lower eyelid taping, continued daily. | Ectropion resolution; Lagophthalmos resolution; Deficit in eye closure (mm); Eyelid function; Photographs of eye closure at rest and maximal active eye closure. | Post surgical treatment: Ectropion—resolved Lagophthalmos—resolved Deficit in eye closure—reduced to 0 mm Eyelid function—competent Photographs—range of motion, eye closure returned to normal at rest and normal active eye closure |

| Elbanoby, Elbatawy [18] 2016 | 4 patients with chemical burns; 8 patients with thermal burns, 2x bilateral ectropion | n = 14 | Initial treatment (Occurred at time of injury in various hospitals): Unilateral FTSG to release both eyelids n = 4; Bilateral FTSG to release both eyelids n = 1; STSG * to release lower eyelid n = 3 Later reconstructive treatment’: Periorbital reconstruction using bifurcated superficial temporal artery island flap (BSTIF). Two patients underwent bilateral periorbital flap reconstruction, 10 patients underwent unilateral reconstruction. | Complications; Eyelid incompetence; Lagophthalmos; Photographs of post-burn scarring | Post reconstructive surgery: Complications—Nil Eyelid incompetence/lagophthalmos—reduced to 0 mm in 10 cases, 1–2 mm in 2 cases Repeated procedure—nil Photographs—post-burn scarring appearance reduced. |

| Hou, Hou [19] 2024 | 26 patients with burns including facial burns | n = 46 | Initial treatment: 6 (9 eyes) had not previously undergone skin grafting or other treatments for eyelid adhesion, while the remaining 20 (37 eyes) had undergone tarsorrhaphy and/or skin grafting after which ectropion recurrence occurred. Reconstructive procedures: The tunnel orbicularis oculi muscle flap technique. FTSG was then performed. Average time from burn to reconstructive treatment was 533 days (range 91 to 183 days). | Average: Adhesion time; Lagophthalmos/eye exposure; Eyelid closure; Eyelid separation (open eyes); Ectropion recurrence; Adhesion failures; Grafting failure rate (%). | Last follow up: Average adhesion time—21.87 months in the 46 eyes Lagophthalmos—resolved Eyelid closure—reduced from 7.72 mm to 0.22 mm Eyelid separation (open eyes)—reduced from 13.89 mm to 8.75 mm Ectropion/contracture recurrence—nil Adhesion failures—nil Grafting failure rate < 2%. |

| Jeong, Alessandri-Bonetti [20] 2024 | 14 patients with facial burns, average 39.5 ± 19.7% TBSA | n = 23 | Acute n = 10; Acute then reconstructive n = 23. First surgery: FTSG: n =9; Skin substitute and FTSG: n = 2 Lateral canthoplasty: n = 2; Fractional lasering: n = 1; Second surgery: FTSG: n = 4; Z-plasty: n = 1; STSG: n = 1 Third surgery: Flap and canthoplasty: n = 1; Skin substitute and FTSG: n = 2 | Success rate in group (n/total (%) in correcting eyelid ectropion without recurrence) | First surgery: FTSG—33.33% Skin substitute and FTSG—100% Lateral canthoplasty—100% Fractional lasering—50% Second surgery: FTSG—50% Z—plasty—100% STSG—100% Third surgery: Flap and canthoplasty—100% Skin substitute + FTSG—50% |

| Jovanovic, Dizdarevic [21] 2018 | 1 patient, 31 years old, 60% TBSA severe deep thermal burns with facial involvement | n = 2 | Initial treatment (out-of-country treatment)—13 surgeries: several necrotomies and the Meek Micrografting technique procedures with two repeated keratinocytes cultures harvesting in their tissue bank. 244 days post injury: bilateral lower eyelid reconstructive surgery—Skin cantus-to-cantus incision, contracture release, orbicularis liberation, and lid elevation; and oversizing free FTSG (Wolfe technique) from the left inguinal region. Residual lower left lid laxity was addressed by pentagonal wedge resection. Decompressive fasciotomy and prolonged treatment for 213 days. | Eyelid closure deficit. Graft take Corneal exposure; Complications | 6 months post-surgery: Eyelid closure deficit—reduced to mild in lower lid Graft take—100% Corneal exposure—no extensive corneal exposure Complications—nil |

| Keilani, De Faria [17] 2021 | 1 patient, 43 years old, 8% TBSA deep dermal to full-thickness chemical burns. | n = 2 | Treatment 11 days post injury (to release contracture and prevent ectropion): Upper and lower eyelid excision and FTSG over two procedures. The peri-orbital areas were derma braded. Combined with eye drops. Each surgical procedure included a two-staged procedure (debridement and FTSG). | Eyelid closure; Cosmetic appearance; Lagophthalmos; Exposure-related complications. | Six months after surgery: Eyelid closure—full Cosmetic appearance—reported as “satisfying” Lagophthalmos—nil Exposure-related complications—nil |

| Lee, Levitt [22] 2018 | 1 patient, 29-year-old, extensive facial burns | n = 1 | 122 days post injury: Reconstructive—adjunctive intralesional 5-FU (5-fluorouracil) injections and AFLR (ablative fractional laser resurfacing) with laser-assisted delivery of topical 5-FU. Delivered over 4 sessions into the periocular scar tissue. | Ectropion; lagophthalmos; Exposure complications; Skin abnormalities; Cosmetics questionnaire (scar appearance) | Ectropion—resolved Lagophthalmos—resolved Exposure complications—nil Skin abnormalities—improved Questionnaire for cosmetics (scar appearance)—POSAS reduced from 89–26. |

| Lymperopoulos, Jordan [23] 2016 | 1 patient, 19 years old, 96% TBSA mostly full thickness burns, facial involvement. | n = 2 | 28 days post injury: Due to early signs of ectropion with corneal exposure bilaterally, skin grafts were required on both lower lids and right cheek: FTSG to lower eyelid, temporary lateral eyelid tarsorrhaphy with forehead hitch using non-absorbable suture material. Suture kept in for 14 days. | Corneal exposure; Ectropion resolution; Photographs (functional/cosmetic); Eyelid closure | 548 days post-surgery: Ectropion—resolved Photographs—excellent functional and cosmetic result at 548 days. Eyelid closure—complete Corneal exposure—0 mm |

| Papadopoulou, Nikolaidou [24] 2023 | 1 patient, 45-year-old with chemical burns; facial involvement, delayed presentation for medical treatment | n = 2 | Surgical: Post injury day 60—FTSG left upper & lower eyelid, FTSG right lower eyelid, partial lateral tarsorrhaphy left. Day 72—FTSG right upper eyelid. Day 146—Repeat FTSG right lower eyelid. Day 474—Tarsorrhaphy release with local flap, Z Plasties, V-Y Plasties to both eyelids and canthal areas. Between surgeries, sessions of triamcinolone acetonide intralesional injection were completed to soften specific areas with hypertrophic scarring. Conservative: custom-made compressive face mask with silicone sheets | Ectropion recurrence; Eyelid closure; Scar maturation; Eyelid competence; Conservative measure—scar contraction | Conservative measure: Unable to prevent scar contraction. 913 days post burn: Ectropion recurrence—nil Eyelid closure—2/2 eyes satisfactory, adequate & unforced Scar maturation—adequate Eyelid competence—deficit reduced but ongoing need for lubrication |

| Takaya, Sakai [25] 2024 | 1 patient, 73-year-old with facial burns, recurring ectropion following previous surgical intervention | n = 1 | Initial approach: FTSG, scar revision, and lateral tarsal strip surgery. Scar recurred with lachrymation, inadequate eyelid closure, and lower eyelid ectropion Reconstructive surgical approach: Horner Muscle suture and fascia graft—left lower eyelid. | Ectropion; Lagophthalmos; Cosmetic complications; Dry eye symptoms; Retraction | Post-surgery: Ectropion—resolved Lagophthalmos—0 mm Cosmetic complications—nil Dry eye symptoms—nil Retraction—5.5 mm |

| Vana, Isaac [26] 2014 | 2 patients, over 18 years of age, with facial burns | n = 3 | Reconstructive/revision post burn (non-acute) Both patients: Subperiostal suspension. Patient 2: Skin grafting bilateral. | Vertical positioning of eyelid margin; Clinical symptoms; Complications; Need for additional surgeries; Skin graft integration. Subjective interview: Clinical symptomatology (yes/no symptom questionnaire); Appearance | Evaluation 274 days post surgery: Vertical positioning of the eyelid margin—average 19% Gain * Integration of skin grafts—100% Clinical symptoms (lacrimation, red eyes, and ocular occlusion difficulty)—Good (improvement of 100% of symptoms) Incidence of complications—nil Need for additional surgeries—nil Subjective interview: Clinical symptomatology (yes or no questionnaire): Symptoms—moderate (>50%) improvement; Appearance—moderate (>50%) improvement |

| Yeşiloğlu, Şirinoğlu [27] 2014 | 17 patients with periorbital burns | n = 17 | Reconstructive surgical technique: Vertical lid V-Y advancement technique. | Ectropion; Lagophthalmos; Presence of major complications; Presence of minor complications; Scar appearance | Post surgical intervention: Ectropion—nil Lagophthalmos—nil Presence of major complications—nil Presence of minor complications —n = 2 minor complications (resolved) Scar appearance—minimal & satisfactory |

| Zucal, Waldner [28] 2022 | 5 patients, with burn TBSA ranging from 36-88% and facial involvement. | n = 10 | Reconstruction 61 to 183 days post injury: Combined FTSG application and lateral canthopexy. Four of five patients underwent further interventions for scar release and FTSG: Canthopexy n = 3 from 2 patients, Scar release and FTSG n = 7 from 4 patients. Case 1: bilateral lower eyelid ectropion and upper eyelid retraction. 152 days post injury: bilateral ectropion correction with scar release of upper and lower eyelid, supraclavicular FTSG, and bilateral canthopexy. 274 days post injury: bilateral ectropion recurrence. Revision surgery—scar release and FTSG. Case 2: 183 days post injury: bilateral FTSG and lateral canthoplexy to correct bilateral ectropion and eyelid axis distortion. 518 days post injury: recurrence of ectropion. Scar release and FTSG. 883 days post injury: re-canthoplasty and additional tarsal strip procedure. 1370 days post injury: scar release and FTSG. Case 3: 91 days post injury: functional correction of the bilateral ectropion with scar release followed by FTSG and lateral canthopexy. 274 days post injury: correction of medial ectropion with medial canthopexy and z-plasty Four years later, another surgical correction and FTSG for medial lower ectropion. Case 4: 61 days post injury: Scar release of upper and lower eyelid, FTSG from cervical area, and lateral canthopexy. Case 5: 183 days post injury: bilateral ectropion of the lower eyelids. Scar release, FTSG (from the right groin), and lateral canthopexy. 274 days post injury: FTSG repeated for recurrent scar contraction. 457 days post injury: re-canthopexy (bilaterally) with scar release and FTSG. | Symmetry; Eyelid closure; Complications; Lagophthalmos and eyelid closure; Recurrence. | Surgical follow up (median 487 (61 to 122 days): Symmetry—improved in all 5 patients Eyelid closure—forced closure restored in 5/5 patients. Complete relaxed eyelid closure bilaterally in 2 patients, complete relaxed closure unilaterally in another 2 patients. Forced closure bilaterally in 1 patient. Complications—nil Exposure symptoms—resolved or reduced Lagophthalmos—reduced to 0–3 mm; in 1 case, there was a reduced but persistent bilateral lagophthalmos (1.5 mm on the right and 3.0 mm on the left), with complete forced closure. Recurrence—surgical revision required n = 2 (recurrence of unilateral lower eyelid retraction). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mc Kittrick, A.; Hammond, L.; Brown, J. Interventions for Functional and Cosmetic Outcomes Post Burn for Eyelid Ectropion—A Scoping Review. Eur. Burn J. 2025, 6, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030046

Mc Kittrick A, Hammond L, Brown J. Interventions for Functional and Cosmetic Outcomes Post Burn for Eyelid Ectropion—A Scoping Review. European Burn Journal. 2025; 6(3):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMc Kittrick, Andrea, Lola Hammond, and Jason Brown. 2025. "Interventions for Functional and Cosmetic Outcomes Post Burn for Eyelid Ectropion—A Scoping Review" European Burn Journal 6, no. 3: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030046

APA StyleMc Kittrick, A., Hammond, L., & Brown, J. (2025). Interventions for Functional and Cosmetic Outcomes Post Burn for Eyelid Ectropion—A Scoping Review. European Burn Journal, 6(3), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030046