Abstract

The jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana and C. frondosa co-occur within some habitats in the Florida Keys, but the frequency with which this occurs is low. It is hypothesized that the symbiosis with different dinoflagellates in the Symbiodiniaceae is the reason: the medusae of C. xamachana contain heat-resistant Symbiodinium microadriaticum (ITS-type A1), whereas C. frondosa has heat-sensitive Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B19). Cohabitation occurs at depths of about 3–4 m in Florida Bay, where the water is on average 0.36 °C cooler, or up to 1.1 °C cooler per day. C. frondosa tends not to be found in the warmer and shallower (<2 m) depths of Florida Bay. While the density of symbionts is about equal in the small jellyfish of the two species, large C. frondosa medusae have a greater density of symbionts and appear darker in color compared to large C. xamachana. However, the number of symbionts per amebocyte are about the same, which implies that the large C. frondosa has more amebocytes than the large C. xamachana. The photosynthetic rate is similar in small medusae, but a greater reduction in photosynthesis is observed in the larger medusae of C. xamachana compared to those of C. frondosa. Medusae of C. xamachana have greater pulse rates than medusae of C. frondosa, suggestive of a greater metabolic demand. The differences in life history traits of the two species were also investigated to understand the factors that contribute to observed differences in habitat selection. The larvae of C. xamachana require lower concentrations of inducer to settle/metamorphose, and they readily settle on mangrove leaves, submerged rock, and sand compared to the larvae of C. frondosa. The asexual buds of C. xamachana are of a uniform and similar shape as compared to the variably sized and shaped buds of C. frondosa. The larger polyps of C. frondosa can have more than one attachment site compared to the single holdfast of C. xamachana. This appears to be an example of niche diversification that is likely influenced by the symbiont, with the ecological generalist and heat-resistant S. microadriaticum thriving in C. xamachana in a wider range of habitats as compared to the heat-sensitive symbiont Breviolum sp., which is only found in C. frondosa in the cooler and deeper waters.

1. Introduction

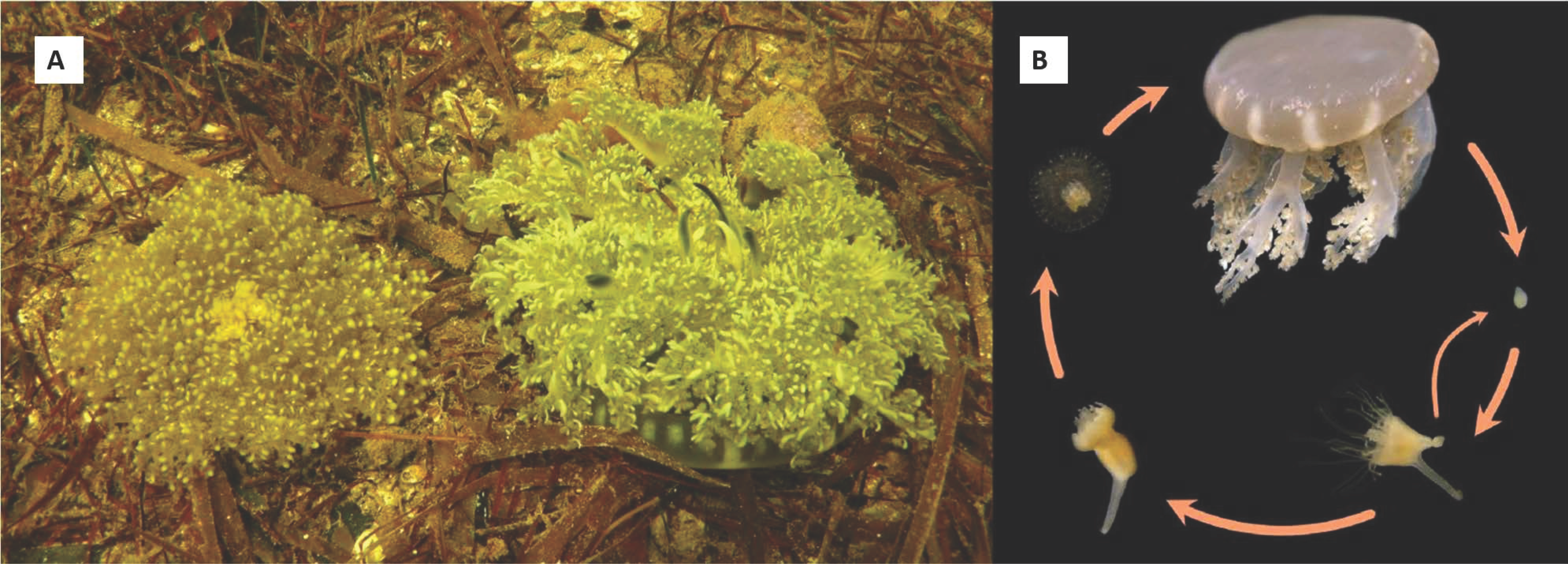

The first species of upside-down jellyfish, Cassiopea frondosa, was described in 1774 from the Caribbean, probably Jamaica [1]; the description of C. andromeda from the Red Sea was published the following year [2]. C. xamachana from the Florida Keys was described about 100 years later by Bigelow [3]. Two of these species, C. frondosa and C. xamachana, co-occur in South Florida, the Bahamas, Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea. Although C. frondosa is typically found in deeper areas, both species can be seen side- by-side on sandy or muddy substrate, in seagrass beds, or among mangrove roots (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Cassiopea frondosa (female) and C. xamachana (male) living together in a deep (3–4 m) channel in Florida Bay. (B) Lifecycle of Cassiopea sp. Eggs hatch into planulae larvae, with both stages lacking symbiotic algae. The planulae metamorphose into scyphistomae (polyps) that acquire symbionts from the environment. Scyphistomae can asexually produce buds that settle into polyps. Symbiotic algae are required for scyphistomae to strobilate into ephyra (immature jellyfish) that subsequently develop into male or female adult medusae.

The life cycle of all species of Cassiopea is assumed to be similar and resemble that of other scyphozoans (Figure 1B), except for one crucial aspect. Cassiopea establishes a symbiotic association with the dinoflagellates of the Symbiodiniaceae family [4] and lives bell-down, typically at the bottom of mangroves or seagrasses. Cassiopea alternates between having an initially aposymbiotic scyphistoma (polyp) form and that of a symbiotic medusa. In fact, the aposymbiotic larvae settle and metamorphose to form an aposymbiotic polyp possessing a mouth, which enables them to engulf and take up the symbiotic dinoflagellates [5]. These Symbiodiniaceae translocate carbon and other molecules, providing nutrients to their host [6]. The acquisition of symbionts leads to a second metamorphic event where the polyps strobilate to give rise to the motile medusa form [7,8].

Ecological theory states that under identical conditions, similar species will compete with each other for the necessary resources they need for survival, resulting in the competitive exclusion of one of the species. C. frondosa and C. xamachana can sometimes be found occupying the same niche. It is unlikely that these two species have fundamentally different lifestyles. However, two similar species can survive together with different symbionts that have different temperature and light tolerances for survival.

The Symbiodiniaceae family encompasses at least 15 genera living in various corals, anemones, hydroids, clams, and jellyfish [4,9,10]. Most of these hosts have one species of detectable Symbiodiniaceae symbiont. However, with global warming, it is thought that having a heat-resistant symbiont species would provide more benefit than a heat-sensitive symbiont species. When a symbiotic system is “open”, meaning that a host can take up more than one symbiont species, a whole new realm of possibilities exist.

Thornhill et al. [11] provided a framework for the symbiosis with C. xamachana. He found that scyphistomae can take up any small Symbiodiniaceae into a symbiosis, and that these symbiotic polyps strobilated with all of those symbionts [12]. However, shortly after stroblilation, the symbiotic algae inside C. xamachana change to a large, heat-tolerant symbiont called Symbiodinium microadriaticum. The interpretation was that the Symbiodiniaceae competed with each other such that S. microadriaticum soon outcompeted all of the other symbionts (competitive exclusion).

As far as we know, no one has performed any long-term analyses of the densities of these jellyfish in seagrass or mangrove ecosystems. The only place where we consistently see C. frondose is in the deeper (3–4 m) parts of Florida Bay. If one were to hypothesize the trends in the populations over time, one would say that C. xamachana might currently have the advantage, in that the medusae house a heat-resistant symbiont in S. microadriaticum, while C. frondosa has a heat-sensitive symbiont (= Breviolum sp. ITS-type B19). With a life cycle that lasts much less than a year, and a high fecundity that takes place during all seasons, we hypothesize that the physiology of C. xamachana is different than that of C. frondosa, and that C. xamachana may be gradually displacing C. frondosa in the warming waters of Florida, the Bahamas, and the Caribbean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Temperature Probes

Temperature probes (HOBO, Onset Computer Corp, Bourne, MA, USA) were placed near the bottom of two sites in Florida Bay where various numbers of C. xamachana and C. frondosa could be found: (1) the nearshore shallow water (1–2 m) in Buttonwood Sound (25.10194, −80.43817), which had many C. xamachana and no C. frondosa, and (2) in a deeper cut (25.12859, −80.44357) extending into Little Buttonwood Sound (3–4 m), which had many C. xamachana and C. frondosa. The probes were collected after 22 d July–August 2017, and the highest and lowest differences of shallow vs. deep temperatures per day (out of six per day) were plotted.

2.2. Symbionts

Dominant phylotype(s) of Symbiodiniaceae from each jellyfish were sampled. DNA was isolated using a modified Promega Wizard genomic DNA extraction protocol (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). A touch-down thermal cycle profile with the primers ‘ITS2clamp’ and ‘ITSintfor2’ was used for PCR amplification of the ITS2 region of the nuclear ribosomal RNA genes. Amplified products were resolved on denaturing gels (45–80% of 7 M urea and 40% deionized formamide) using a CBS Scientific system (Del Mar, CA, USA) for 10 h at 150 V at a constant temperature of 60 °C. To verify that DGGE banding patterns corresponded exactly with phylotype designations, samples were run in parallel to sequenced markers [9,11].

To determine the density of symbiont cells, adult C. xamachana and C. frondosa were first blotted dry with paper towels, weighed, measured, and then a small piece was cut from the bell and weighed. The small piece was ground with a homogenizer and a small volume of seawater, after which the volume of the slurry was measured, the number of symbionts were subsequently counted with a hemocytometer, which was then multiplied to obtain the total number per jellyfish.

Symbionts in Cassiopea jellyfish, as a particular feature, reside in amebocytes within the mesoglea. To determine the density of symbiont cells housed within the host amoebocytes, a thin layer of mesoglea was spread under a microscope, and the number of dinoflagellate cells were enumerated for the first 100 amebocytes of five jellyfish from each species. The symbionts were surrounded by the membrane of the amebocyte. Additionally, the diameter of 100 symbiont cells were measured from both male and female jellyfish.

Algal samples from a portion of the jellyfish (6 of each species) were analyzed for chlorophyll content. Acetone was added to the frozen pellet and the volume was measured; the resulting mixture was homogenized, allowed to develop overnight at −20 °C, centrifuged (1500 rpm, 3–5 min), and absorbances were read on a spectrophotometer. Chl a was calculated by multiplying the proportion using the equations of Jeffery and Humphrey [13].

The photosynthesis of jellyfish was determined in variously sized quartz containers that were submerged in Florida Bay in the middle (10 AM–4 PM) of sunny days (ca. 1400 μE m−2 sec−1). Oxygen was measured with the Vernier Optical Dissolved Oxygen Probe, which required no calibration nor stirring. The jellyfish mixed the water by pulsing, with linear measurements extending for 15–30 min. Measurements were made when the temperatures were 29.0 ± 0.5 °C. The intensity of sunlight was read with a LI-COR LI 185B photometer and the diameter of the bell was measured to determine the surface area and the wet weight.

2.3. Settlement and Metamorphosis

Planulae larvae of C. xamachana and C. frondosa were obtained from brooding female medusae and maintained in 35 ppt Instant Ocean. Four replicate wells (1.0–1.5 mL) of approximately 10–20 larvae per well were used in the experiments. In the first experiment, the planulae were exposed to either 20, 10, 5, or 0 μg/mL of the peptide inducer Z-Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Pro-Ala-OH for 1, 2, or 3 days. In the second experiment, larvae were exposed to the natural substrates from shallow water—either small pieces of aged mangrove leaf, the seagrasses Thalassia testudinum and Halodule wrightii, rock, sand, or a control—for 1, 2, 3, or 4 days. Comparisons of responses were made between C. xamachana and C. frondosa.

2.4. Scyphistomae

The metamorphosis of larvae into polyps was observed. As the polyps grew larger, they started to produce buds, and the buds settled and metamorphosed into polyps. When the calyx of the polyps was about 2 mm in diameter and had obtained an appropriate symbiont, they were observed to strobilate into medusae. Observations and comparisons were made in each of these transitions for C. xamachana and C. frondosa.

2.5. Medusae

Medusae show hydrodynamic pulsing behavior via a cyclic bell contraction. The number of pulses per minute was recorded 10 min after moving five of the medusae of C. xamachana and five of the C. frondose to measuring containers. The temperature of the seawater was 29.0 °C, and all measurements were made in the shade during the middle of the day. The diameters of medusae were measured.

3. Results

3.1. Location, Size, and Quantities of Symbionts

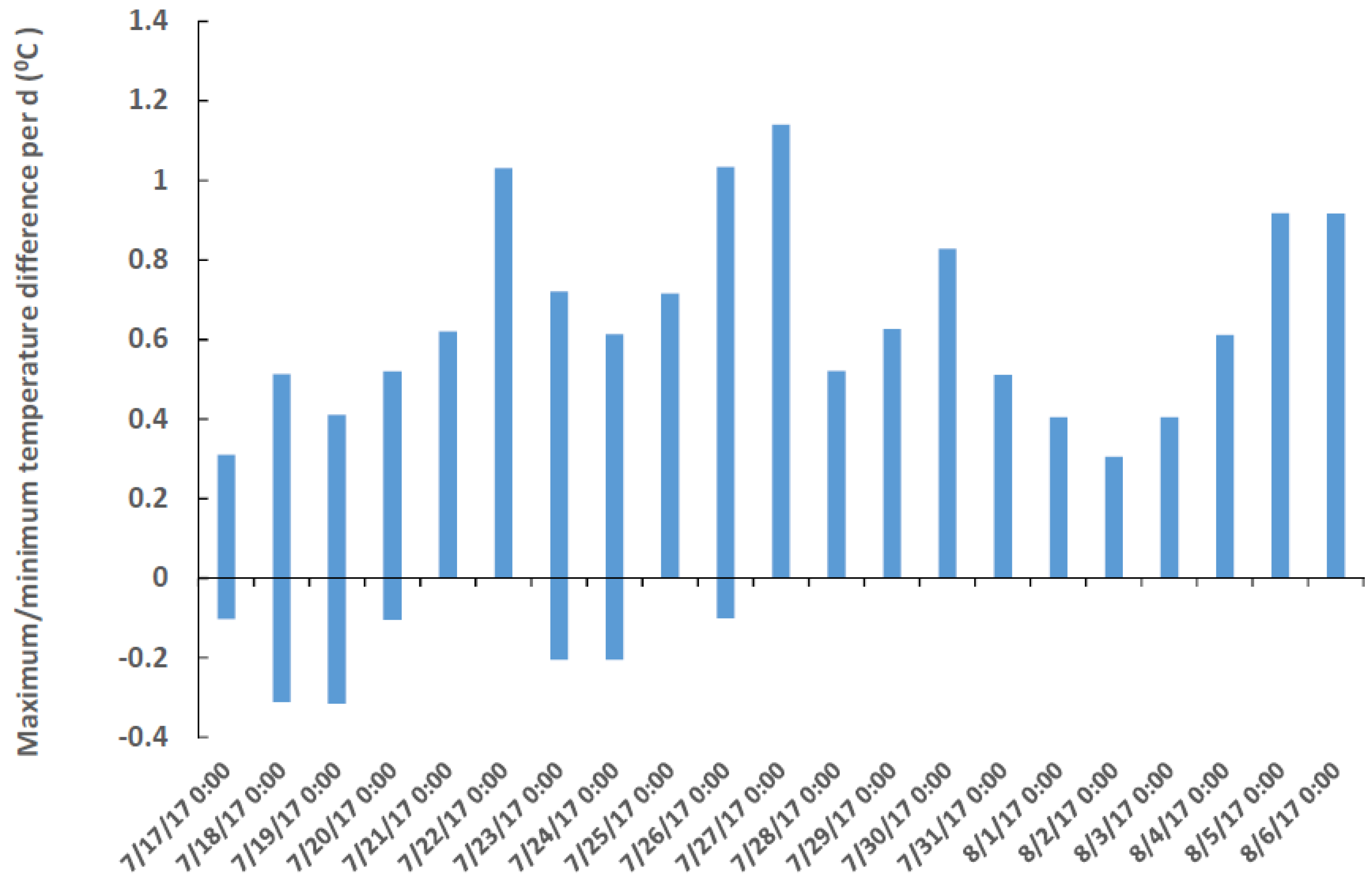

All medusae of the C. xamachana sampled contained S. microadriaticum, the temperature-tolerant species found in virtually all post-ephyra adults. The C. frondosa were colonized by the heat-sensitive Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B19). Given the temperature tolerance of the symbionts, the only place where both jellyfish co-occur is in cooler, deeper habitats (e.g., 3–4 m) that tend to be on average 0.36 ± 0.28 °C (s.d., n = 132) cooler at the bottom compared to shallow water habitats (1–2 m) (Figure 2). The temperature was as much as 1.1 °C higher in shallow vs. deep water during the 6 measurements each day (Figure 2). Peak temperatures varied between 29 °C and 34 °C and usually occurred at 6 PM; the coolest temperature usually occurred at 10 AM each day. The largest difference in temperature between the surface and the deep areas occurred in the daytime, between 10 AM and 10 PM (0.43 ± 0.26, n = 82), as compared to nighttime (0.26 ± 0.23, n = 42) (t = 3.307, p < 0.001). Light intensity was most probably less in deeper water, but it was not measured. The medusae of C. frondosa are darker in color than those of C. xamachana because they have a different symbiont species that is more numerous in larger medusae (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Maximum and minimum temperature differences (from six measurements per day) between a shallow habitat (1–2 m) containing only C. xamachana vs. a deeper habitat (3–4 m) containing both C. frondosa and C. xamachana. Temperatures ranged from 29 °C to 34 °C, and negative values indicate occasions when the shallower habitat was colder than the deeper habitat. Days go from midnight (0:00) to midnight.

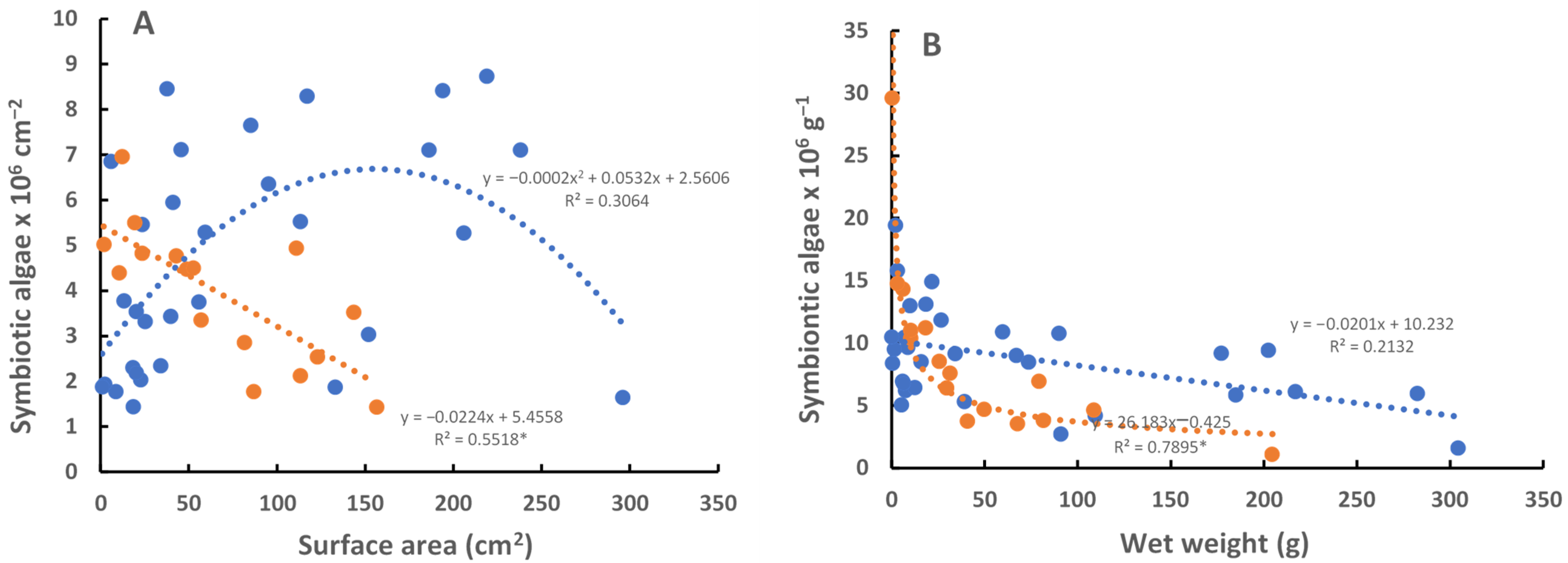

Figure 3.

Number of symbiotic algae in the medusae of C. frondosa (blue, n = 30) and C. xamachana (red, n = 16): (A) per cm2 of the bell surface area, (B) per gram of wet weight. Regressions with * are significant (p < 0.05).

Number of symbionts per amebocyte was similar in C. xamachana (6.66 ± 3.68, n = 5) and C. frondosa (5.79 ± 4.04, n = 5). However, there were apparently more amebocytes in the large (>10 cm diameter) medusae of C. frondosa, such that they contained a higher total number of symbionts and looked much darker than the large (>10 cm diameter) medusae of C. xamachana (Figure 3). Symbiodinium microadriaticum (A1) isolated from C. xamachana have a larger diameter (male 9.9 ± 0.8 µm, female 10.1 ± 0.9 µm; n = 100) and twice the volume of Breviolum sp. (B19) isolated from C. frondosa (male 7.4 ± 0.8 µm, female 7.3 ± 0.6 µm; n = 100), and contain about twice the chlorophyll-a per symbiont (C. xamachana male 2.4 ± 0.5 µg/cell, female 2.0 ± 0.4 µg/cell n = 6; C. frondosa male 1.3 ± 0.4 µg/cell, 1.1 ± 0.5 µg/cell, n = 6).

3.2. Photosynthesis of Symbionts

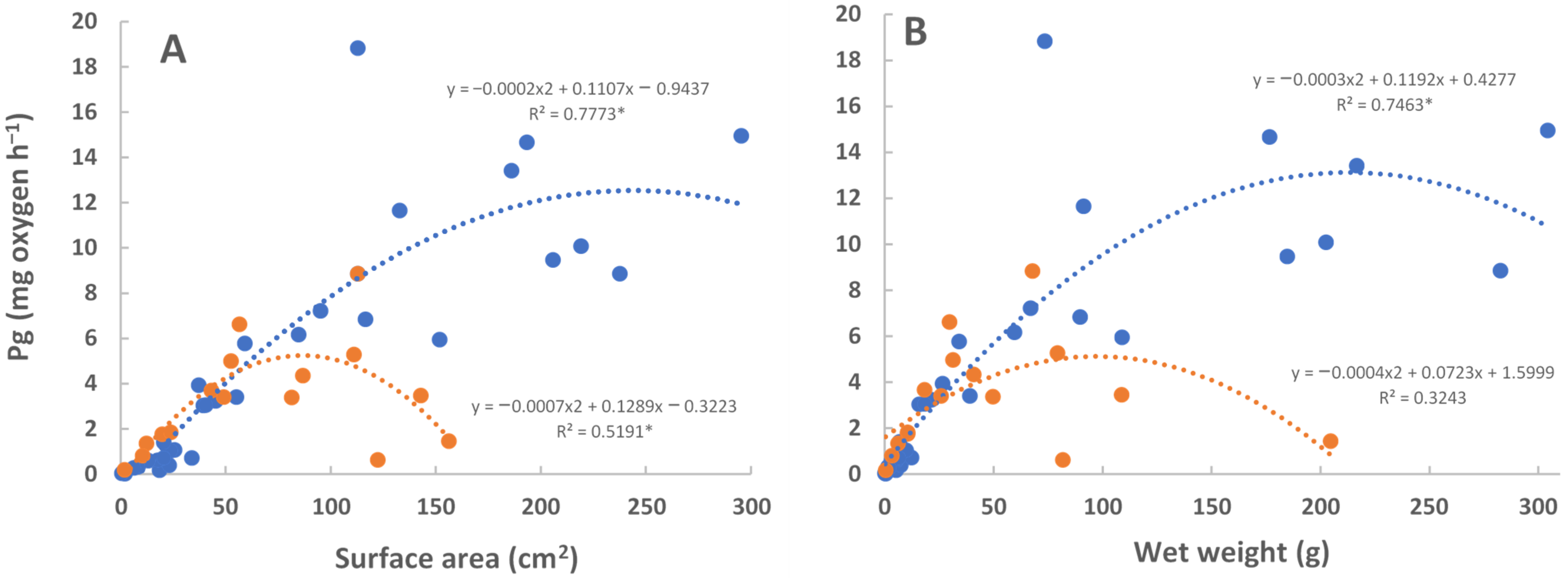

A higher rate of photosynthesis was observed for the larger medusae (>80 cm2, >80 g wet weight) of C. frondosa as compared with the similarly sized C. xamachana (Figure 4). Photosynthetic rates of smaller medusae were not distinguishable. Light intensity (1000–1750 µE m−2 sec−1) was above saturation for all measurements.

Figure 4.

Gross photosynthesis (mg O2 h−1) of medusae of C. xamachana (red, n = 16) and C. frondosa (blue, n = 30) per (A) bell surface area (cm2) and (B) wet weight (g). Regressions with * are significant (p < 0.05).

3.3. Scyphistomae

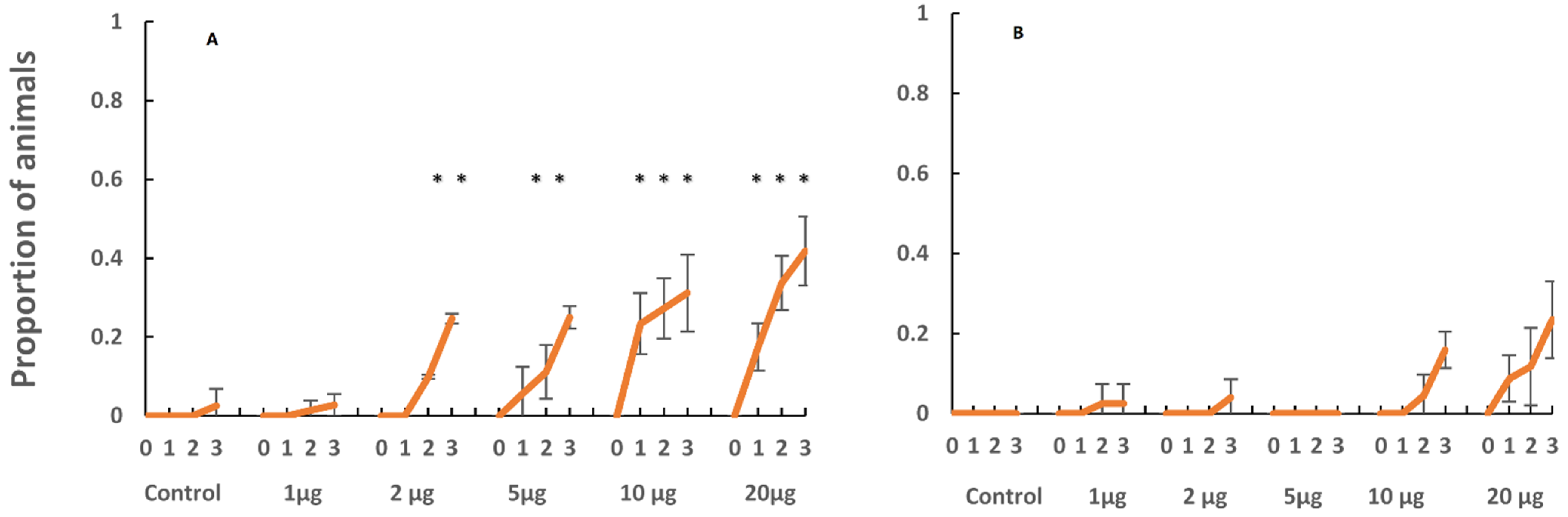

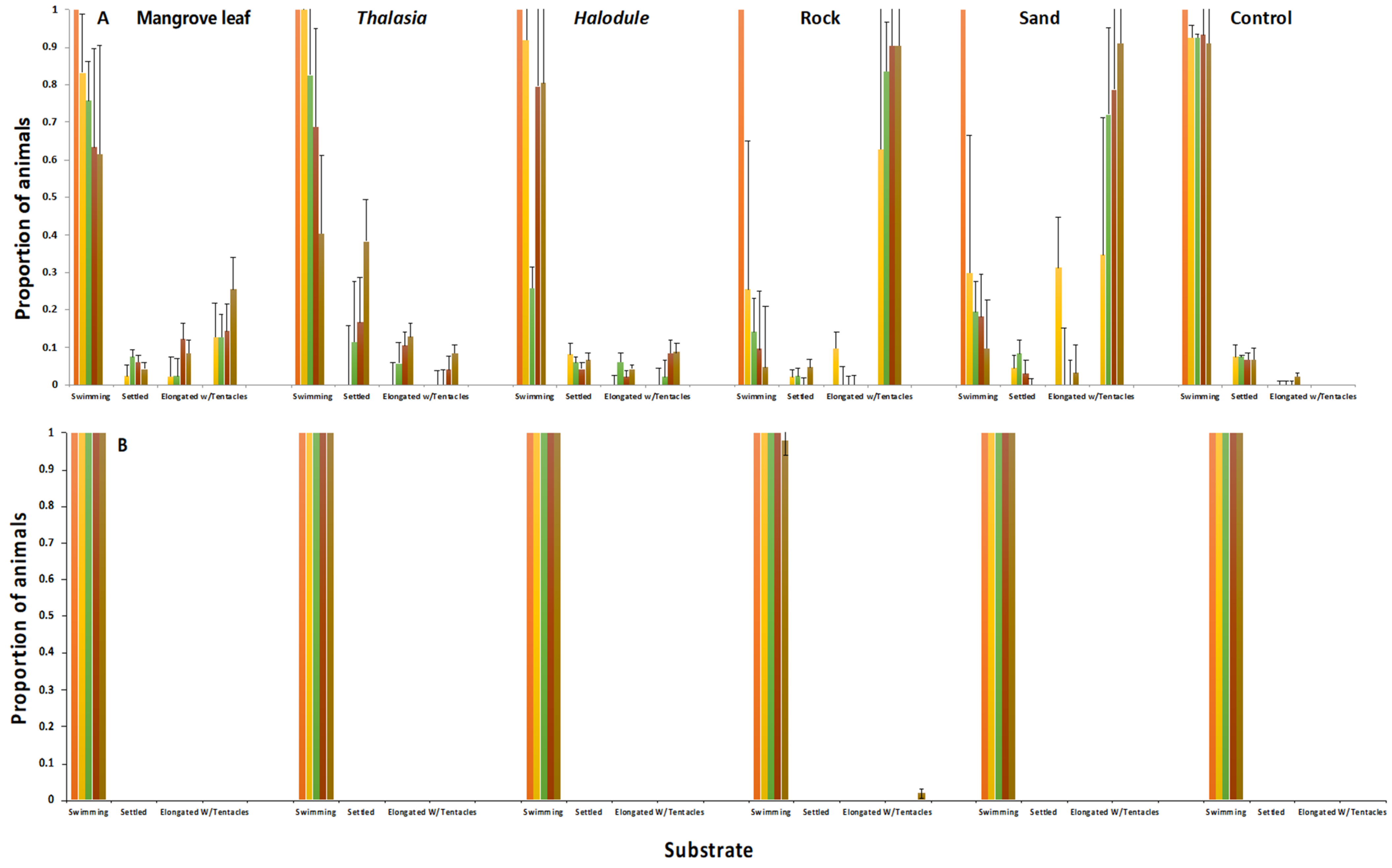

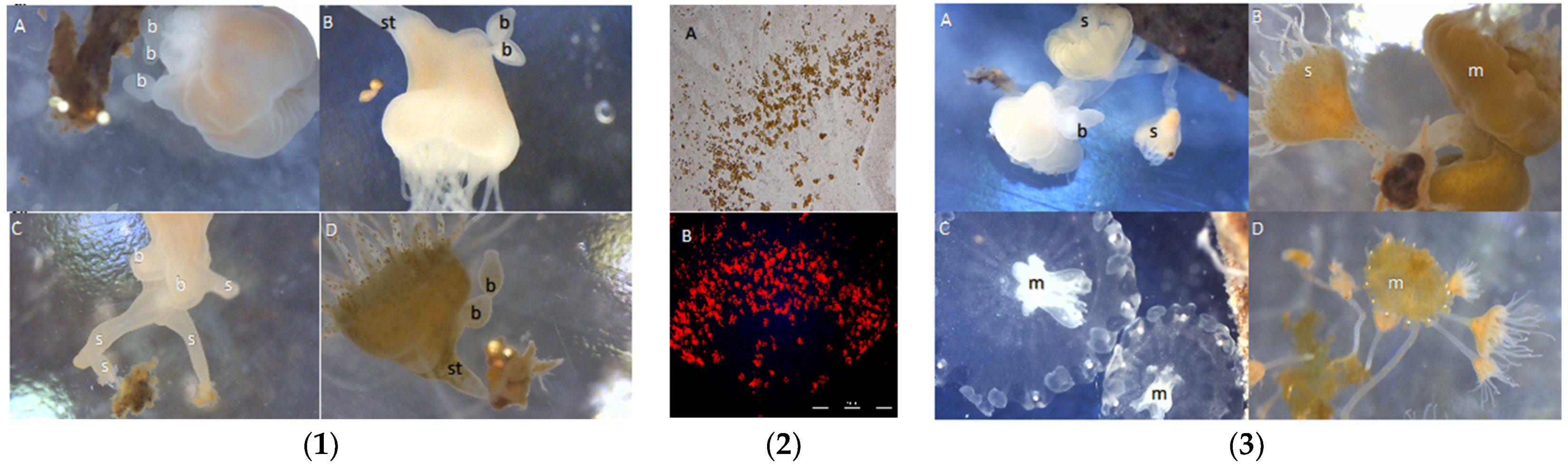

When chemically induced to settle and metamorphose in the laboratory, the planulae of C. xamachana settled and metamorphosed into scyphistomae with an order of magnitude less inducer as compared to the planulae of C. frondosa (Figure 5). Settlement into scyphistomae on natural substrates was observed (Figure 6); C. xamachana tended to settle onto natural substrates at much greater densities than C. frondosa, especially on mangrove leaves, rocks, and sand. As the polyps grew larger, they began to produce buds, and the buds of C. xamachana settled and metamorphosed into polyps at greater rates than the buds of C. frondosa (Figure 7(1)). When the polyps of C. xamachana (Figure 7(2)) and C. frondosa were infected with symbionts and grew to a sufficient size (calyx diameter approximately 2 mm), and when the temperature was above 25 °C, they were observed to strobilate into medusae (Figure 7(3)).

Figure 5.

Settlement and metamorphosis into polyps of C. xamachana (A) and C. frondosa (B) in response to the inducer Z-GLY-PRO-GLY-GLY-PRO-ALA-OH for 0, 1, 2, or 3 days. Mean ± s.d. (n = 4). The proportion of metamorphosed polyps of C. xamachana were significantly higher (*, comparison of means) than metamorphosed polyps of C. frondosa.

Figure 6.

Settlement and metamorphosis of C. xamachana (A) and C. frondosa (B) on substrates from a shallow habitat (1–2 m) for 4 days (orange = Day 0, yellow = Day 1, green = Day 2, maroon = Day 3, brown = Day 4). Mean ± s.d. (n = 4).

Figure 7.

(1) Scyphistomae of C. frondosa (A,C) and C. xamachana (B,D). C. frondosa has asymmetrical buds (b) and often times multiple stolons (s) ending in attachment of large polyps, whereas C. xamachana has symmetrical buds (b) and one attachment at end of the stalk (st). (2) Symbiotic algae in digestive cells and amebocytes in scyphistomae of C. xamachana in (A) incandescent and (B) epiflourescent light. Symbionts are about 10 µm in diameter. (3) Strobilating scyphistomae (s) and medusae (m) of C. frondosa (A,C) and C. xamachana (B,D). b = bud, bright white dots around the edge of medusa are rhopalia (C. frondosa has exactly 12, C. xamachana has 11–23).

3.4. Medusae

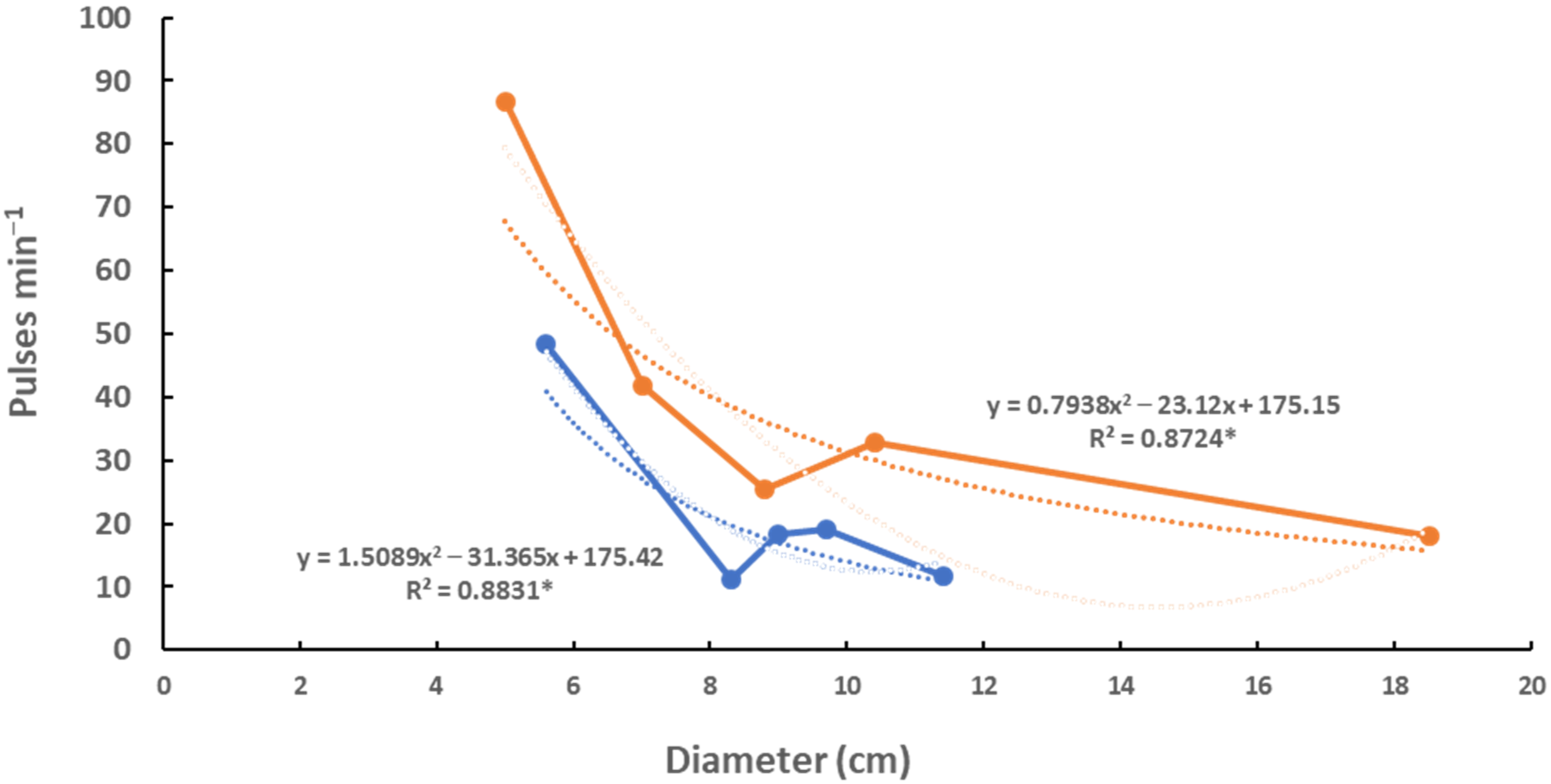

The pulse rate is thought to estimate the metabolic rate of Cassiopea sp. [14]. The pulse rate of C. xamachana is about 50% higher than the pulse rate of C. frondosa (Figure 8), implying that C. xamachana has a higher metabolism than C. frondosa.

Figure 8.

Pulse rates of C. xamachana (red) and C. frondosa (blue). Regressions with * are significant (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

C. xamachana and C. frondosa are found to co-occur along the Florida Keys. C. frondosa are typically found at greater depths compared to C. xamachana, potentially as an adaptive strategy for forming a symbiosis with the temperature-sensitive species of Breviolum (B19). C. frondosa is consistently found with C. xamachana in the deeper parts of Florida Bay. The physiology of C. xamachana is fundamentally different from that of C. frondosa, and C. xamachana may be gradually displacing C. frondosa in the shallow warm waters of Florida, the Bahamas, and the Caribbean. These marked differences in development and physiology underlie differences in the two populations of upside-down jellyfish observed in the Florida Keys.

4.1. Settlement and Metamorphosis

Developing planulae larvae were taken from the stalked vesicles on the oral disk of the sexually mature female medusae of C. xamachana and C. frondosa. The hatched planulae were of similar size and behavior i.e., [15]. However, they showed pronounced differences in settlement responses to both a chemical inducer and to natural substrates. When the planulae were induced to settle with the peptide Z-GLY-PRO-GLY-GLY-PRO-ALA-OH, C. xamachana responded at lower concentrations in contrast to the planulae of C. frondosa (Figure 5). In addition, the planulae of C. xamachana settled at the bottom of old, submerged mangrove leaves, and nearshore sand and rocks, while the planulae larvae of C. frondosa showed no conclusive settlement affinity towards the shallow water substrates offered in this experiment (Figure 6). It appears that either the biofilms inducing the settlement and metamorphosis differ in the shallows vs. deeper sites, or the detection of cues differs between the two species of jellyfish, with C. xamachana becoming competent to settle quicker than C. frondosa. Additionally, C. frondosa may have a more complex stimulus-response system, requiring additional cues not provided in these experiments.

4.2. Bud Formation and Metamorphosis

Buds form easily in C. xamachana, coming off the bottom of the calyx of the scyphistomae in similar sized oblong beads (Figure 7(1B,D)). Buds of C. frondosa also come from the bottom of the calyx, but in haphazard shapes and sizes (Figure 7(1A,C)). In addition, stolon-like extensions protrude from the stalk of C. frondosa and appear to anchor to the polyp with multiple attachment sites, unlike the single attachment in C. xamachana (Figure 7(1C,D)). Both types of buds metamorphose on degrading mangrove leaves and dead seagrasses to form scyphistomae. Aposymbiotic scyphistomae of Cassiopea xamachana take up almost any Symbiodiniaceae from the seawater (Figure 7(2A,D)), but are eventually dominated by S. microadriaticum (formerly ITS-type A1) shortly after they strobilate [11]. We know very little about which symbionts are taken up and which cause strobilation in C. frondosa, though scyphistomae and adult medusae (Figure 7(3A,C)) have been found with the symbiont Breviolum sp. (formerly B19) (LaJeunesse unpublished). It is unclear why S. microadriaticum does not replace Breviolum sp. in C. frondosa, though the former may be too large for the digestive cells in C. frondosa and have additional requirements associated with its large size [12].

4.3. Medusa

Symbiont types are in constant flux in the scyphistomae of C. xamachana, stabilizing shortly after strobilation when the dominant type apparently outcompetes all others [11]. While C. xamachana is known to strobilate with species of Symbiodiniaceae ≤ 10 µm in diameter [12], only S. microadriaticum (A1) is seen in medusae greater than 1 cm in diameter in the field [11]. No such experiments have been performed on C. frondosa as yet; the range of symbiont types held in symbiosis is currently unknown. But we do know that only Breviolum sp. (B19) is currently found in adult C. frondosa from South Florida (LaJuenesse, unpublished).

An analysis of amebocytes showed approximately the same number of symbionts per amebocyte in C. xamachana and C. frondosa. There are apparently many more amebocytes in larger (>10 cm diameter) C. frondosa as compared with larger (>10 cm diameter) C. xamachana. An analysis of C. xamachana and C. frondosa showed that while immature medusae had roughly similar densities of symbionts, the number of Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B19) symbionts in large medusae far exceeded S. microadriaticum in July–August when the temperatures ranged from 29 °C to 32 °C (Figure 3).

The photosynthetic rate is higher in large C. frondosa than in larger C. xamachana due to the higher densities of symbionts (Figure 3). There are several things that are not known about the photosynthesis of the symbionts at this point: (1) the reasons for the general decrease in the number of symbionts with the size of the jellyfish (assumed to be a function of light availability or the competition of symbionts for limited resources), (2) the reason for the bell-shaped curves of photosynthesis with the size of the jellyfish (per surface area, wet weight, diameter of bell; again assumed to be a function of light availability), and (3) the relative amount of carbon received by the jellyfish from their symbionts. Of course, this could all be much different depending on the year the study is performed (e.g., during El Niño events in 1997–1998, 2014–2016), or the time of year (e.g., winter, spring, fall). For instance, if the measurement is performed when there is no temperature stress (e.g., spring), one might see a very different photosynthetic response.

Pulse rates are thought to represent metabolic rates [14,16] and have also been shown to correlate diurnally with a sleep-like behavior [17]. Pulse rates were determined at mid-day in May 2019, and were about twice as high in similarly sized C. xamachana as compared to those in C. frondosa (Figure 8). This is probably due to the difference in metabolic rate in the two species, perhaps indicating physiological differences between the two different symbionts. It would be interesting to know the limitations on the symbionts and host, and how this relates to the metabolic rates (Figure 8) of the two species of jellyfish.

4.4. Climate Change

Late summer and early fall are the periods with the highest temperature in the Florida Keys. Bleaching during this time could be significant since the symbionts provide over 160% of the carbon requirement of C. xamachana medusae [18]. Heat-resistant S. microadriaticum (ITS-type A1) is known to function normally at ≤ 32 °C [19,20] and C. xamachana can survive in water as warm as 36 °C [21]. The heat-sensitive Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B19) symbionts are thought to become less efficient at fixing carbon as temperatures increase past 29 °C, and they presumably become inactive and exit the host at > 31 °C.

Two symbiont species can have pronounced differences in response to the same temperature: e.g., differences in growth rates, respiration and photosynthetic rates, stability of lipid membranes; all of these are possible. Putting this together, a 1.1 °C or less difference in temperature (Figure 2) could make a significant difference in their ability to survive, especially at the critical temperatures of 29–32 °C. Robison and Warner [22] documented differences in the dark-acclimated Fv/Fm (photosynthetic potential) and the critical D1 protein of S. microadriaticum (relatively stable) vs. a heat-sensitive Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B1) (decreases markedly) at 32 °C in elevated light. Enhanced cell death and necrosis in thermally exposed symbionts were noted in intact symbioses as growth decreased rapidly in S. microadriaticum or ceased completely in Breviolum sp. at 32 °C and high light. In addition, Iglesias-Prieto [19] showed a rapid decrease (13–22% per degree C) in the whole-cell fluorescence of S. microadriaticum at temperatures greater than 32 °C.

Observations of relatively small differences in temperature between the cooler-deeper and the warmer-shallower water is probably enabling the Breviolum sp. in C. frondosa to survive in the summers in the Florida Keys. Anecdotal sightings of C. frondosa in the shallow waters of Buttonwood Sound were extremely rare over the past 30 years, but the species is seen consistently in the deeper (3–4 m) sections of Florida Bay. These observations are probably due to the physiological differences between C. xamachana and C. frondosa, especially concerning the different symbionts occurring in the jellyfish.

4.5. Conclusions

Cassiopea xamachana has a heat-resistant symbiont, Symbiodinium microadriaticum, and is found in most Florida Bay habitats, while C. frondosa has the heat-sensitive symbiont, Breviolum sp. (ITS-type B19), and is only found in cooler-deeper water in Florida Bay. Deeper habitats tend to be cooler and shadier than shallow ones, and this appears to be one of the driving factors of the physiological differences between the two species. Symbiont densities, photosynthesis, chlorophyll, size, and the ability of larvae to settle and metamorphose on natural substrates and in response to an artificial inducer were different, as was the pulse rate (= metabolic rate). This appears to be an example of distribution as determined by the type of symbiont.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.F., D.K.H., D.W.K. and A.H.O.; methodology, W.K.F., D.K.H., D.W.K. and A.H.O.; writing—original draft preparation, W.K.F.; writing—review and editing, W.K.F., D.K.H. and A.H.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Key Largo Marine Research Laboratory and the University of Georgia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pallas, P.S. Description of Medusa frondosa. In Spicilegia Zoologica; Lange: Berlin, Germany, 1774; Volume 10, pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Forskål, P. Quae in Itinere Orientali Observavit Petrus Forskål. In Descriptiones Animalium Avium, Amphibiorum, Piscium, Insectorum, Vermium; Ex Officina Mölleri: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1775. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow, R.P. On a new species of Cassiopea from Jamaica. Zool. Anz. 1892, 15, 212–214. [Google Scholar]

- LaJeunesse, T.L.; Parkinison, J.E.; Gabrielson, P.W.; Jeong, H.J.; Reimer, J.D.; Voolstra, C.R.; Santos, S.R. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2570–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colley, N.J.; Trench, R.K. Selectivity in phagocytosis and persistence of symbiotic algae by the scyphisto-ma stage of the jellyfish Cassiopeia xamachana. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1983, 219, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mortillaro, J.M.; Pitt, K.A.; Lee, S.Y.; Meziane, T. Light intensity influences the production and translocation of fatty acids by zooxanthellae in the jellyfish Cassiopea sp. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2009, 378, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.K.; Kremer, B.P. Carbon metabolism and strobilation in Cassiopea androrneda (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa): Significance of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates. Mar. Biol. 1981, 65, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrnann, D.K.; Fitt, W.K.; Fleck, J. Checkpoints in the lifecycle of Cassiopea spp.: Control of metagenesis and metamorphosis in a tropical jellyfish. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1996, 40, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- LaJeunesse, T.L. Diversity and community structure of symbiotic dinoflagellates from the Caribbean coral reefs. Mar. Biol. 2002, 141, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

- LaJeunesse, T.C. Validation and description of Symbiodinium microadriaticum, the type species of Symbiondinium (Dinophyta). J. Phycol. 2017, 53, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornhill, D.J.; Daniel, M.W.; LaJeunesse, T.C.; Bruns, B.U.; Schmidt, G.W.; Fitt, W.K. Natural infections of aposymbiotic Cassiopea xamachana scyphistomae from environmental pools of Symbiodinium. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 338, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitt, W.K. Effect of different strains of the zooxanthella Symbiodinium microadriaticum on growth and survival of their coelenterate and molluscan hosts. In Proceedings of the 5th International Coral Reef Congress, Tahiti, French Polynesia, 27 May 1985; Volume 6, pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S.W.; Humphrey, G.F. New Spectrophotometric Equations for Determining Chlorophylls a, b, c and c2 in Higher Plants, Algae and Natural Phytoplankton. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 1975, 167, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClendon, J.F. The direct and indirect calorimetry of Cassiopea xamachana. J. Biol. Chem. 1917, 32, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitt, W.K.; Hofmann, D.K. The effects of the UV-Blocker Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3) on planulae swimming and metamorphosis of the Scyphozoans Cassioipea xamachana and Cassiopea frondosa. Oceans 2020, 1, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangum, C.P.; Oakes, M.J.; Shick, J.M. Rate-temperature responses in scyphozoan medusae and polyps. Mar. Biol. 1972, 15, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.D.; Bedbrook, C.N.; Abrams, M.J.; Basinger, T.; Bois, J.S.; Prober, D.A.; Sternberg, P.W.; Gradinaru, V.; Goentoro, L. The jellyfish Cassiopea exhibits a sleep-like state. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2984–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verde, E.A.; McCloskey, L.R. Production, respiration, and photophysiology of the mangrove jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana symbiotic with zooxanthellae: Effect of jellyfish size and season. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 167, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias-Prieto, R.; Matta, J.L.; Robins, W.A.; Trench, R.K. Photosynthetic response to elevated temperature in the symbiotic dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum in culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10302–10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diaz-Almeyda, E.M.; Prada, C.; Ohdera, A.H.; Moran, H.; Civitello, D.J.; Iglesias-Prieto, R.; Carlo, T.A.; LaJeunesse, T.C.; Medina, M. Intraspecific and interspecific variation in thermotolerance and photoacclimation in Symbiodinium dinoflagellates. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284, 20171767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fitt, W.K.; Costley, K. The role of temperature in survival of the polyp stage of the tropical rhizostome jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1998, 222, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.D.; Warner, M.E. Differential impacts of photoacclimation and thermal stress on the photobiology of four different phylotypes of Symbiodinium (Pyrrhophyta). J. Phycol. 2006, 42, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).