Comparative Evaluation of Screw Loosening in Zirconia Restorations with Different Abutment Designs

Abstract

1. Introduction

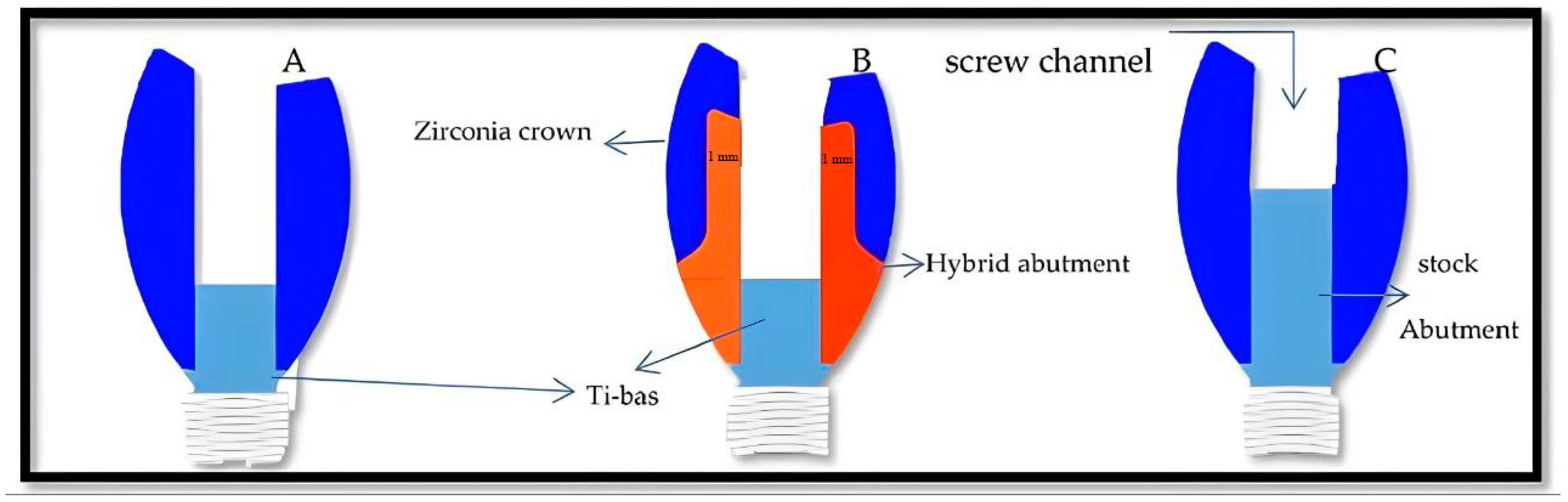

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

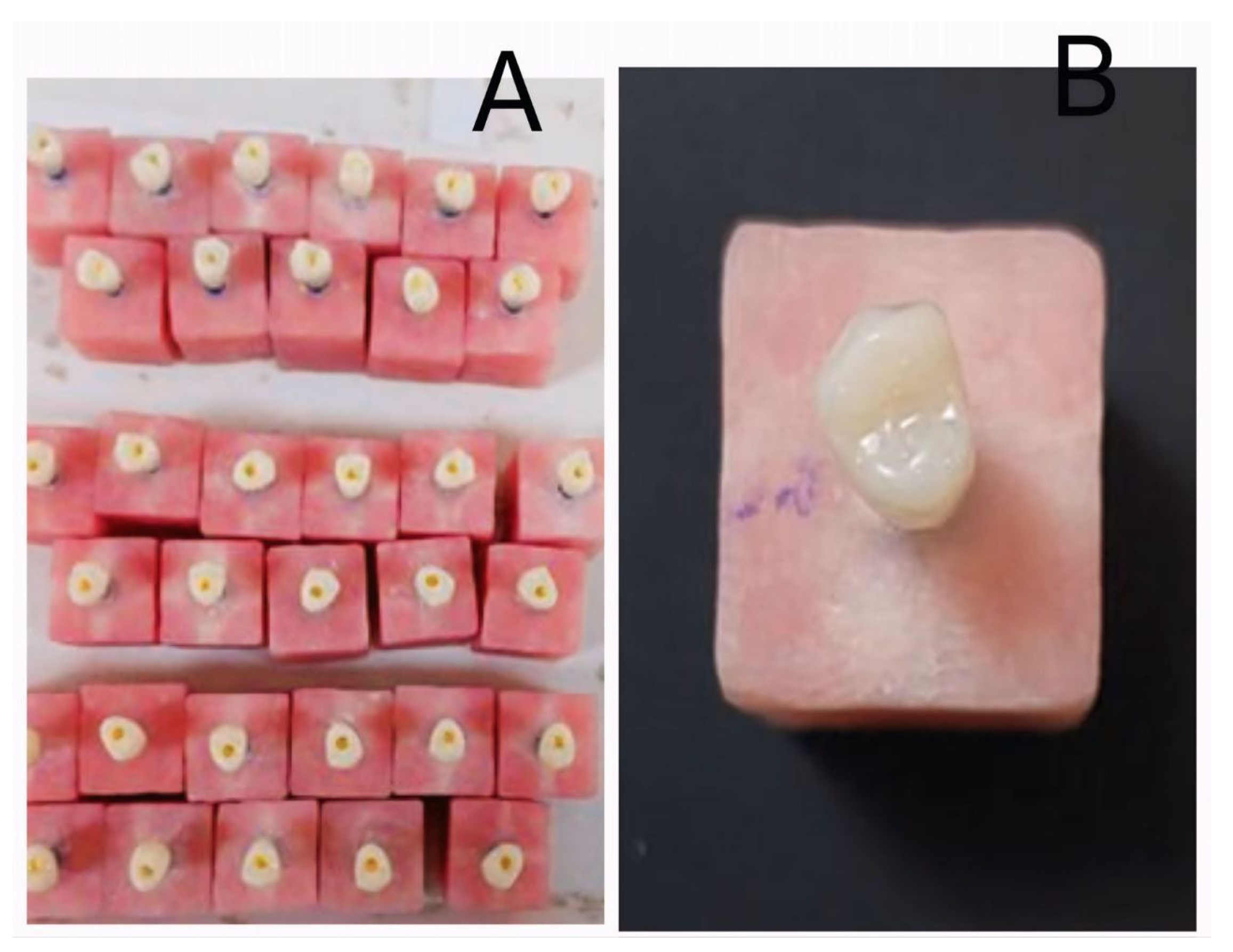

2.2. Sample Mounting

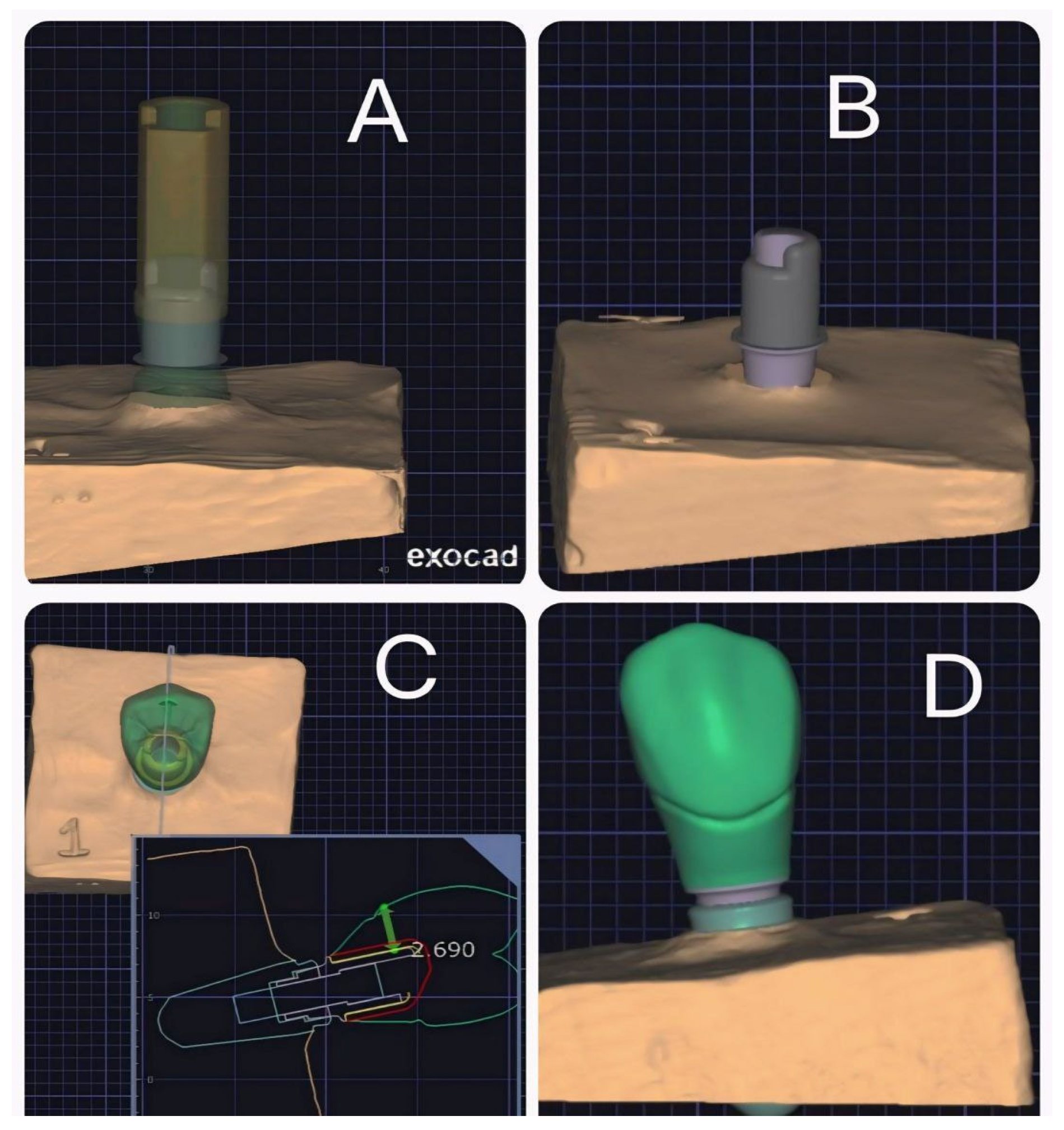

2.3. Scanning the Samples

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. Parameters of the Crown

2.6. Fabrication of Restorations

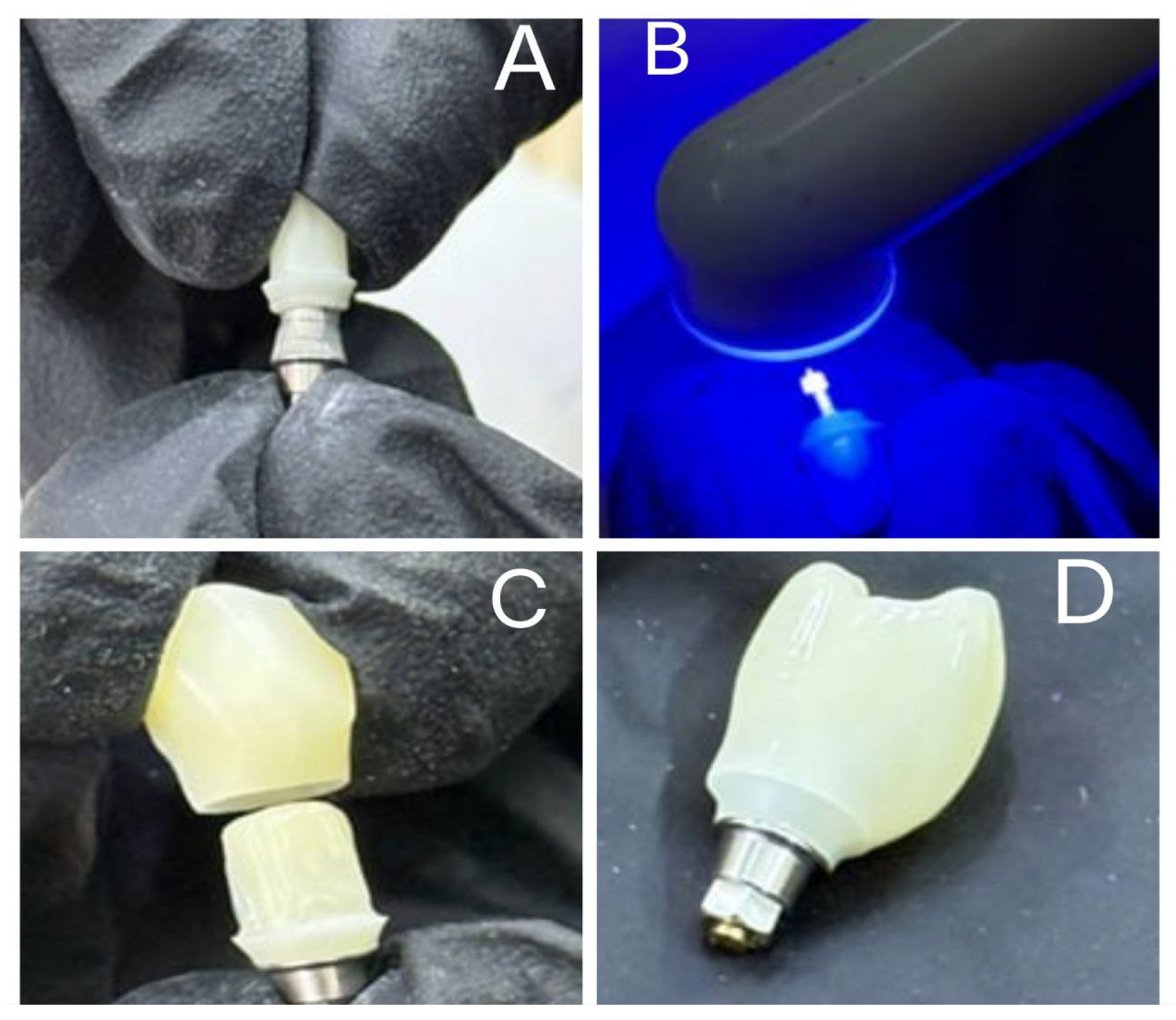

2.7. Surface Treatment

2.8. Cementation Protocol

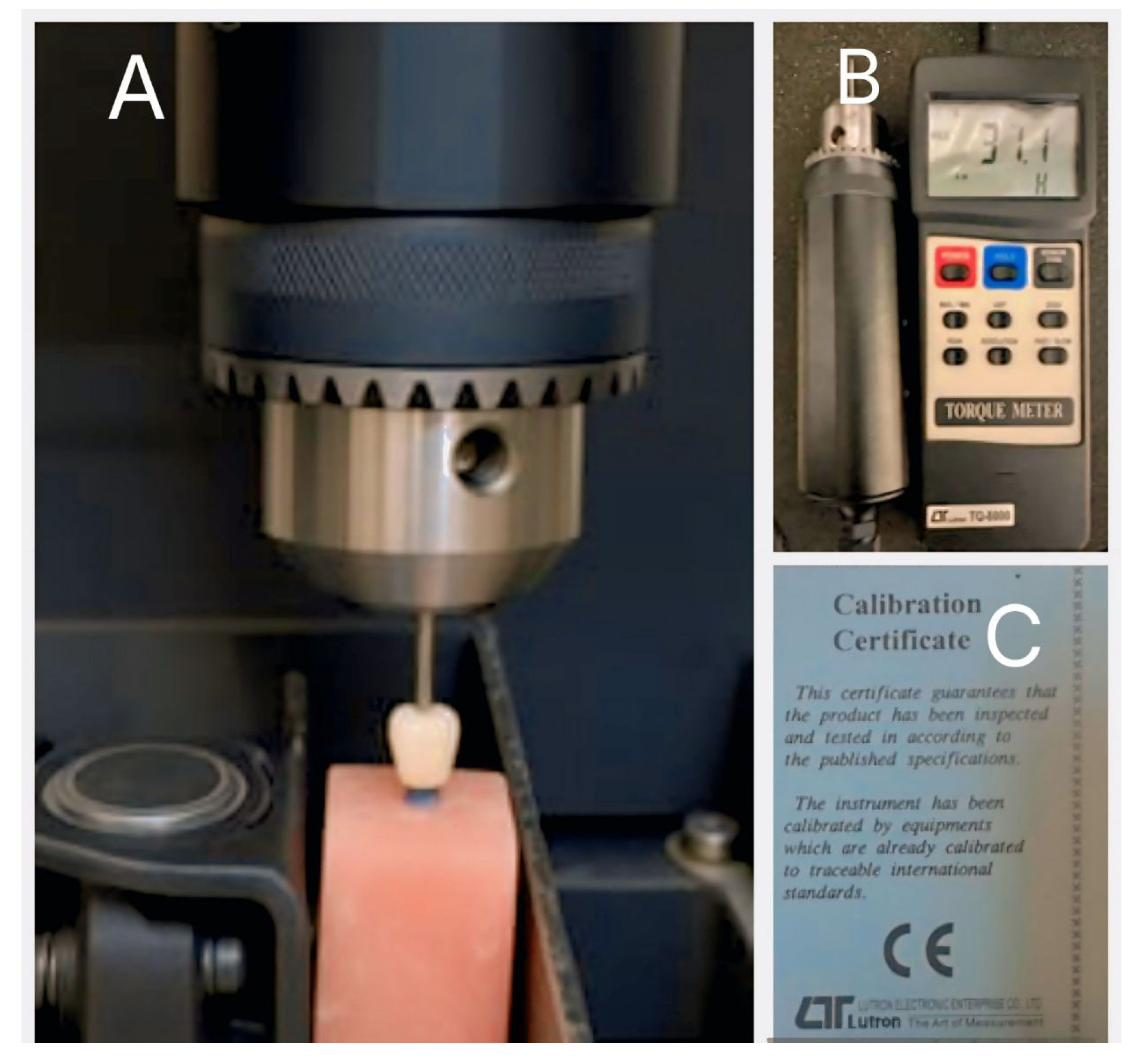

2.9. Measurement of Preloading Removal Torque (RTV1)

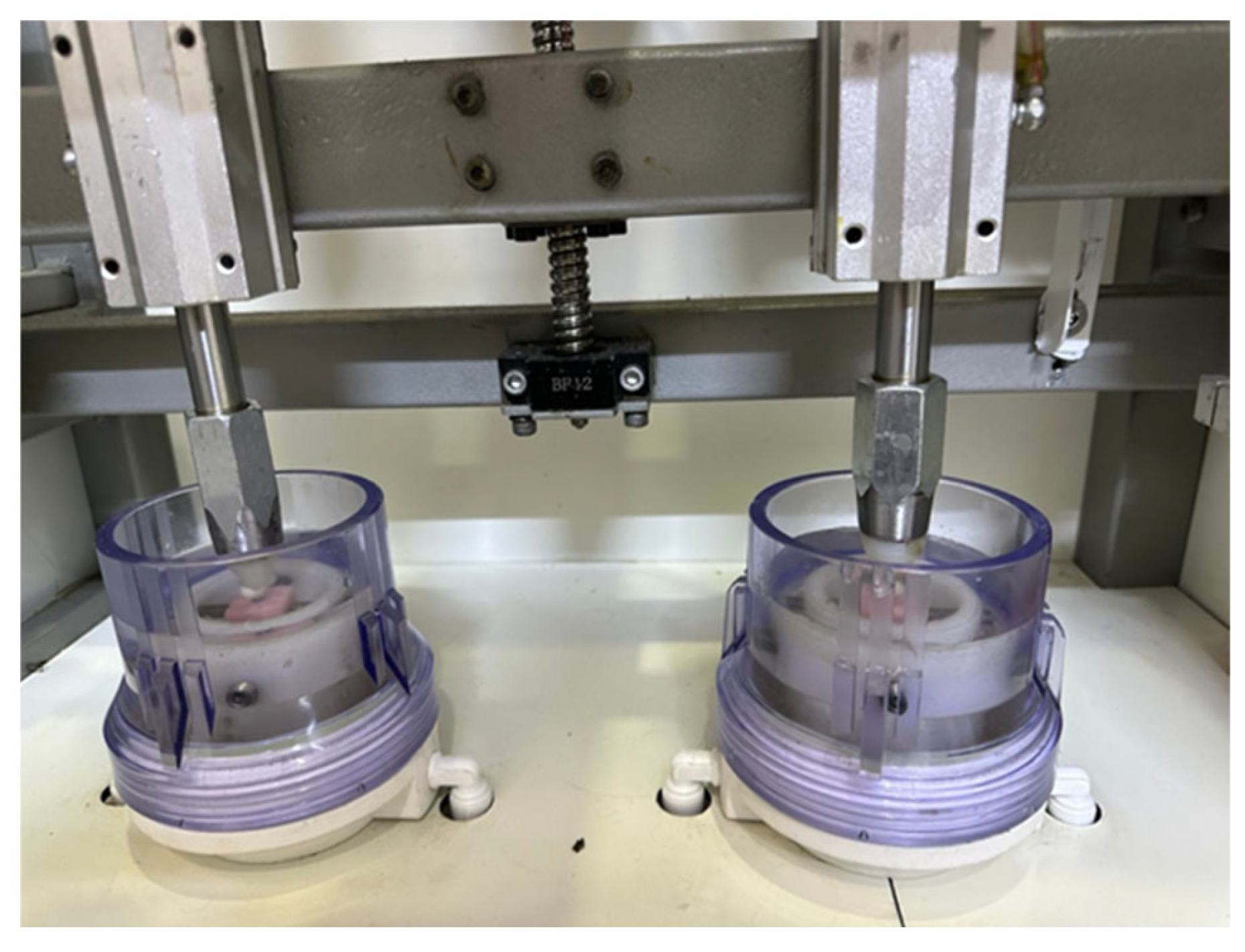

2.10. Artificial Aging

2.11. Measurement of Post-Loading Removal Torque (RVT2)

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Normality Test

3.2. Paired t-Test Comparing Removal Torque Before and After Aging

- In Group A, the mean removal torque decreased from 31.6 Ncm to 27.9 Ncm.

- In Group B, torque decreased from 31.1 Ncm to 28.7 Ncm.

- In Group C, torque decreased from 31.5 Ncm to 28.9 Ncm.

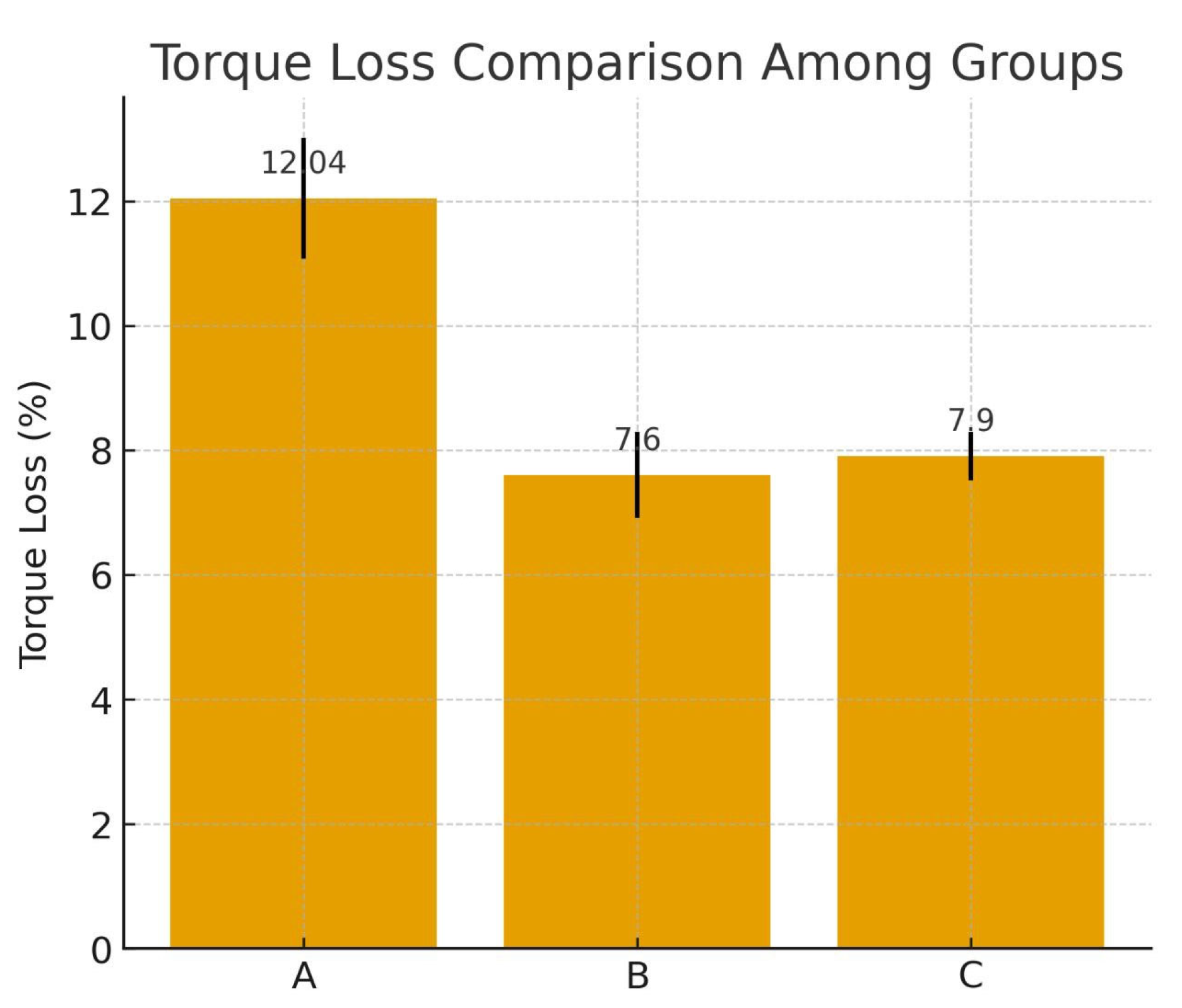

3.3. Torque Loss Percentage (RTL%)

3.4. Post Hoc Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| °C | Degree Celsius |

| µm | Micrometer |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| Hz | Hertz |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| N.cm | Newton Centimeter |

| PMMA | Polymethyl Methacrylate |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| RTL% | Removal Torque Loss Percentage |

| RTV | Removal Torque Value |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| STL | Standard Tessellation Language (file format) |

| Ti-base | Titanium Base |

References

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Chen, C.J.; Singh, M.; Weber, H.P.; Gallucci, G. Success criteria in implant dentistry: A systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moraschini, V.; Poubel, L.D.C.; Ferreira, V.F.; Barboza, E.D.S.P. Evaluation of survival and success rates of dental implants reported in longitudinal studies with a follow-up period of at least 10 years: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas, R.; Sánchez, D.; Euán, R.; Flores, A.M. Effect of fatigue loading and failure mode of different ceramic implant abutments. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonyatpour, M.; Giti, R.; Erfanian, B. Implant angulation and fracture resistance of one-piece screw-retained hybrid monolithic zirconia ceramic restorations. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.; Farrag, G.; Chaar, M.S.; Abdelnabi, N.; Kern, M. Influence of different CAD/CAM crown materials on the fracture of custom-made titanium and zirconia implant abutments after artificial aging. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 32, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarri, M.; Hjerppe, J.; Romeo, D.; Fickl, S.; Thompson, V.P.; Stappert, C.F.J. Marginal accuracy of three implant-ceramic abutment configurations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2012, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Cavusoglu, Y.; Akça, K.; Gürbüz, R.; Cehreli, M.C. Joint stability at the zirconium or titanium abutment/titanium implant interface: A pilot study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimmelmayr, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Güth, J.F.; Erdelt, K.; Happe, A.; Beuer, F. Wear at the titanium–titanium and titanium–zirconia implant–abutment interface: A comparative in vitro study. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thobity, A.M. Titanium base abutments in implant prosthodontics: A literature review. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, T.; Schweiger, J.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Erdelt, K.; Schubert, O.; Güth, J.F. Influence of monolithic restorative materials on the implant–abutment interface of hybrid abutment crowns: An in vitro investigation. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 67, 450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, P.; Alkan Demetoğlu, G.; Talay Çevlik, E. Effect of cement type on vertical marginal discrepancy and residual excess cement in screwmentable and cementable implant-supported monolithic zirconia crowns. Odontology 2024, 112, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhr, M.W.Z.F.; Alansary, H.; Hassanien, E.E.Y. Internal fit and marginal adaptation of all-ceramic implant-supported hybrid abutment crowns with custom-milled screw-channels on titanium-base: In vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouh, I.; Kern, M.; Sabet, A.E.; Aboelfadl, A.K.; Hamdy, A.M.; Chaar, M.S. Mechanical behavior of posterior all-ceramic hybrid-abutment-crowns versus hybrid-abutments with separate crowns: A laboratory study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, A.; Wille, S.; Al-Akhali, M.; Kern, M. Effect of fatigue loading on the fracture strength and failure mode of lithium disilicate and zirconia implant abutments. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J. Mechanism of and factors associated with the loosening of the implant abutment screw: A review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ülkü, S.Z.; Kaya, F.A.; Uysal, E.; Gülsün, B. Clinical evaluation of complications in implant-supported dentures: A 4-year retrospective study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 6137–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Srivastava, S. A study on screw loosening in dental implant abutment. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 53, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çötert, I.; Ulusoy, M.; Türk, A.G. In-vitro comparison of screw loosening, fracture strength and failure mode of implant-supported hybrid-abutment crowns and screwmentable crowns manufactured with different materials. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2025, 28, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabih, D.Q.; Jasim, H.H.; Sabih, D.Q. Comparative evaluation of fracture strength of implant supported crown fabricated from CAD/CAM and 3D printed resin matrix ceramic. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrairo, B.M.; Piras, F.F.; Lima, F.F.; Honório, H.M.; Duarte, M.A.H.; Borges, A.F.S.; Rubo, J.H. Comparison of marginal adaptation and internal fit of monolithic lithium disilicate crowns produced by four different CAD/CAM systems. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, N.D.; Senna, P.M.; Gomes, R.S.; Del Bel Cury, A.A. Influence of luting space of zirconia abutment on marginal discrepancy and tensile strength after dynamic loading. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 683.e1–683.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakmak, G.; Subaşı, M.G.; Sert, M.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of surface treatments on wear and surface properties of dental ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 130, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preis, V.; Hahnel, S.; Behr, M.; Rosentritt, M. In vitro performance and fracture resistance of novel CAD/CAM ceramic molar crowns loaded on implants and human teeth. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2018, 10, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyor, P.; Verma, A.; Meena, K.L.; Meena, R.; Choudhary, S.; Singh, A. Fracture resistance of monolithic translucent zirconia crown bonded with different self-adhesive resin cement: Influence of MDP-containing zirconia primer after aging. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, J.; Jasim, H.H. Fracture resistance of premolars restored with inlay/onlay composite and lithium disilicate CAD/CAM block restorations: An in vitro study. Mustansiriya Dent. J. 2023, 19, 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaiy, E.F. Abutment screw loosening in implants: A literature review. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5490–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamos, G.; Winkler, S.; Boberick, K.G. The relationship between implant preload and screw loosening on implant-supported prostheses. J. Oral Implantol. 2002, 28, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendi, A.; Mirzaee, S.; Falahchai, M. The effect of different implant-abutment types and heights on screw loosening in cases with increased crown height space. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsiri, S.; Arksornnukit, M.; Homsiang, W.; Kamonkhantikul, K. Effect of restoration design on the removal torque loss of implant-supported crowns after cyclic loading. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2023, 24, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, Z.; Sleibi, A. Effect of deep margin elevation on fracture resistance of premolars restored with ceramic onlay: In vitro comparative study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2023, 15, e446–e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Almohaimen, M.; Atef, A.; Ali, A.; Mahmoud, S. Impact of various lining materials on fracture resistance of CAD/CAM fabricated ceramic onlays subjected to thermo-mechanical cyclic loading. Egypt Dent. J. 2023, 69, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, A.M.; El-Kateb, M.M.; Azer, A.S. The effect of two preparation designs on the fracture resistance and marginal adaptation of ceramic crowns using CAD/CAM technology. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaoğlu, Ö.; Nemli, S.K.; Bal, B.T.; Güngör, M.B. Comparison of screw loosening and fracture resistance in different hybrid abutment crown restorations after thermomechanical aging. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2024, 39, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zordk, W.; Elmisery, A.; Ghazy, M. Hybrid-abutment-restoration: Effect of material type on torque maintenance and fracture resistance after thermal aging. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2020, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, M.B.; Diken Türksayar, A.A.; Olcay, E.; Sahmali, S. Fracture resistance of single-unit implant-supported crowns: Effects of prosthetic design and restorative material. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.; Torres, M.F.; Lourenço, E.J.V.; Telles, D.M.; Rodrigues, R.C.S.; Ribeiro, R.F. Torque removal evaluation of prosthetic screws after tightening and loosening cycles: An in vitro study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemt, T. Cemented CeraOne and porcelain fused to TiAdapt abutment single-implant crown restorations: A 10-year comparative follow-up study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2009, 11, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalaei, S.; Rajabi Naraki, Z.; Nematollahi, F.; Beyabanaki, E.; Shahrokhi Rad, A. Stress distribution pattern of screw-retained restorations with segmented vs. non-segmented abutments: A finite element analysis. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects 2017, 11, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bratu, E.; Mihali, S.; Jivanescu, A. The use of a screw sealer in implant abutment fixation. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 11, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihali, S.; Canjau, S.; Bratu, E.; Wang, H.L. Utilization of ceramic inlays for sealing implant prosthesis screw access holes: A case-control study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2016, 31, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Name of Abutment | Restoration Configuration | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Hybrid Abutment Crown | One-Piece Zirconia Crown And Abutment Milled As A Single Monolithic Unit And Bonded To A Ti-Base | Screw-Retained |

| B | Hybrid Abutment | Two-Piece Hybrid Zirconia Abutment + Crown; Custom Zirconia Abutment Bonded To A Ti-Base; Zirconia Crown Cemented Separately | Screw-Retained |

| C | Stock Titanium Abutment | Prefabricated Titanium Abutment With CAD/CAM Zirconia Crown | Screw-Retained |

| Group | Statistic | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (one-piece hybrid abutment crown) | 0.90 | 12 | 0.17 |

| Group B (two-piece restoration) | 0.94 | 12 | 0.62 |

| Group C (stock abutment with zirconia crown) | 0.90 | 12 | 0.18 |

| Group | Pairs | Mean Diff (Ncm) | SD | 95%cl | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | RTV1-RTV2 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.99–3.61 | 40 | <0.001 |

| B | RTV1-RTV2 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.43–2.17 | 38 | <0.001 |

| C | RTV1-RTV2 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.56–2.44 | 54 | <0.001 |

| Group | N | Mean of % | Sd (Stander Deviation) | 95% cl | MIN | MAX | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 12 | 12.04 | 0.97 | 12.66–11.42 | 10.6 | 14.0 | <0.001 |

| B | 12 | 7.6 | 0.69 | 8.04–7.16 | 6.2 | 8.5 | |

| C | 12 | 7.9 | 0.39 | 8.15–7.65 | 7.4 | 9.3 |

| Group (I) | Group (J) | Mean Diff | SE | 95% CI Lower–Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | 4.42 | 0.30 | 3.82–5.02 | p < 0.001 |

| A | C | 4.10 | 0.30 | 3.50–4.70 | p < 0.001 |

| B | C | −0.32 | 0.30 | −0.92–0.28 | NS (p = 0.53) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, Z.A.; Jasim, H.H. Comparative Evaluation of Screw Loosening in Zirconia Restorations with Different Abutment Designs. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060161

Abbas ZA, Jasim HH. Comparative Evaluation of Screw Loosening in Zirconia Restorations with Different Abutment Designs. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060161

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Zainab Ahmed, and Haider Hasan Jasim. 2025. "Comparative Evaluation of Screw Loosening in Zirconia Restorations with Different Abutment Designs" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060161

APA StyleAbbas, Z. A., & Jasim, H. H. (2025). Comparative Evaluation of Screw Loosening in Zirconia Restorations with Different Abutment Designs. Prosthesis, 7(6), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060161