Fit Accuracy and Shear Peel Bond Strength of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Versus Conventional Stainless Steel Space Maintainers: In Vitro Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Groups and Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. Band Fabrication and Selection

2.5.1. Digitally Fabricated Space Maintainers

2.5.2. Group 1: Milled PEEK Bands

2.5.3. Group 2: Additively Manufactured Co-Cr Bands

2.5.4. Group 3: Stainless Steel Bands

2.6. Fit Accuracy Test

2.6.1. Working Cast Preparation

2.6.2. Digital Scanning and Reference Models

2.6.3. Band Seating and Secondary Scanning

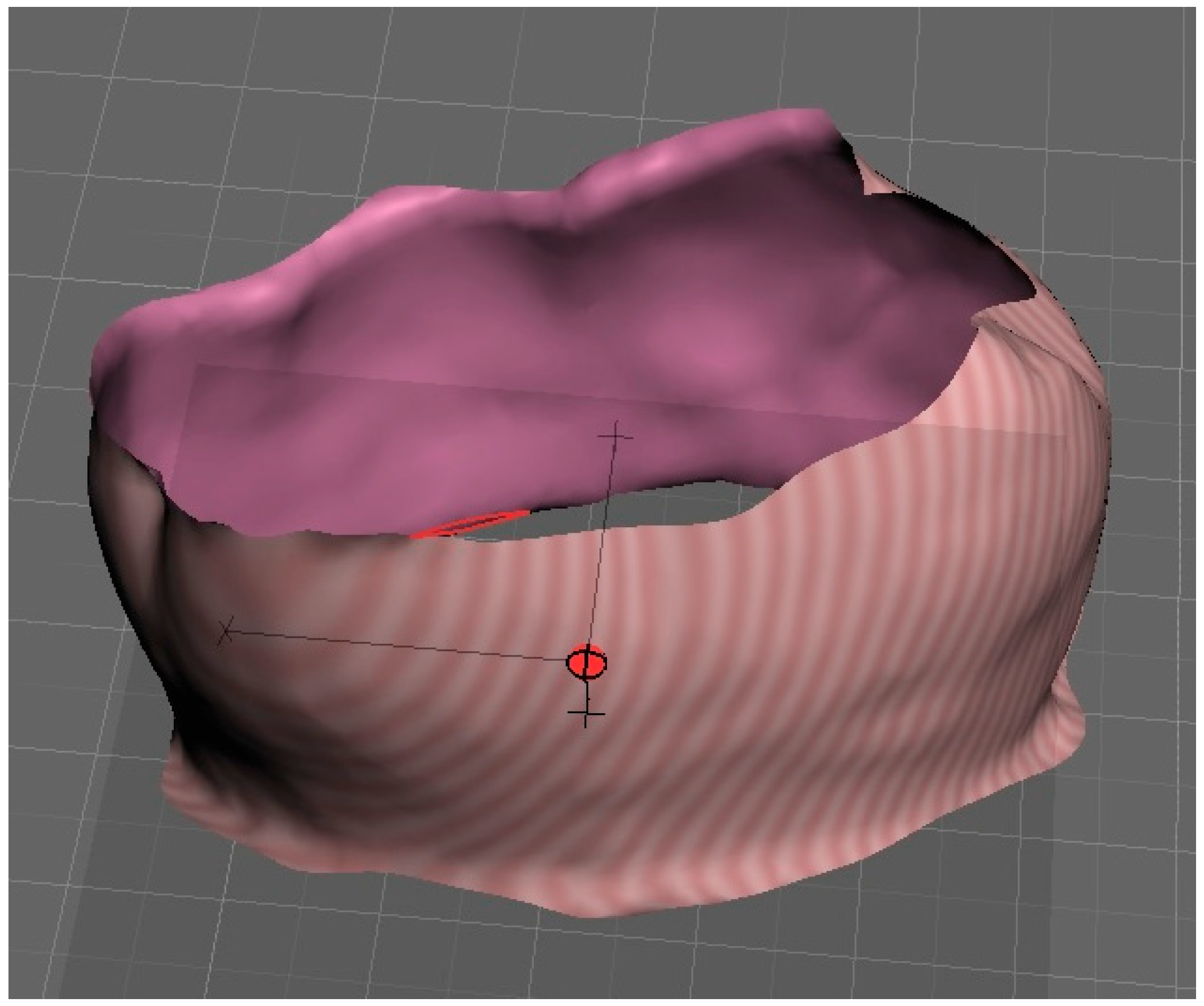

2.6.4. Three-Dimensional Superimposition and Accuracy Analysis

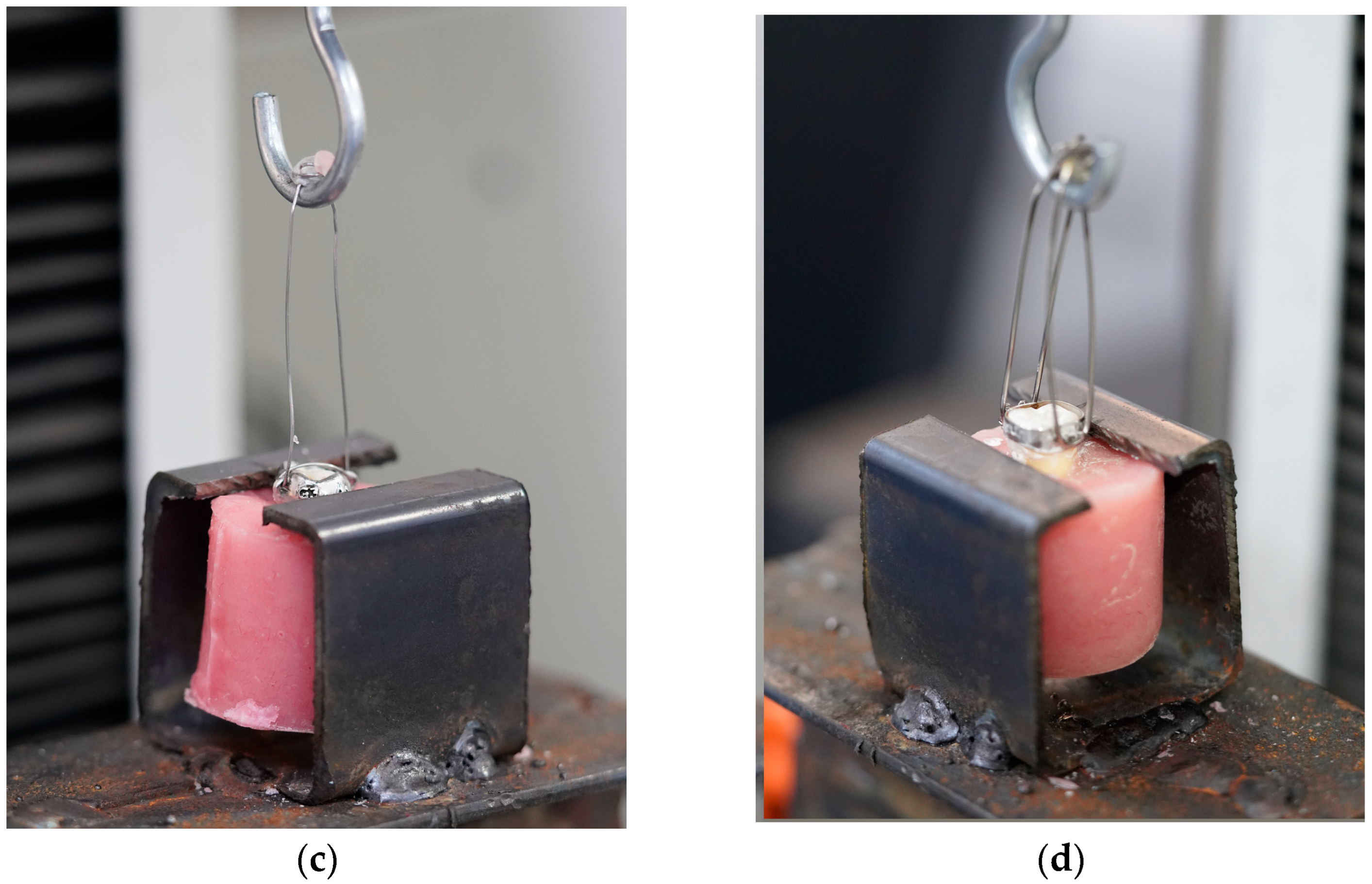

2.7. Shear Bond Strength Test

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

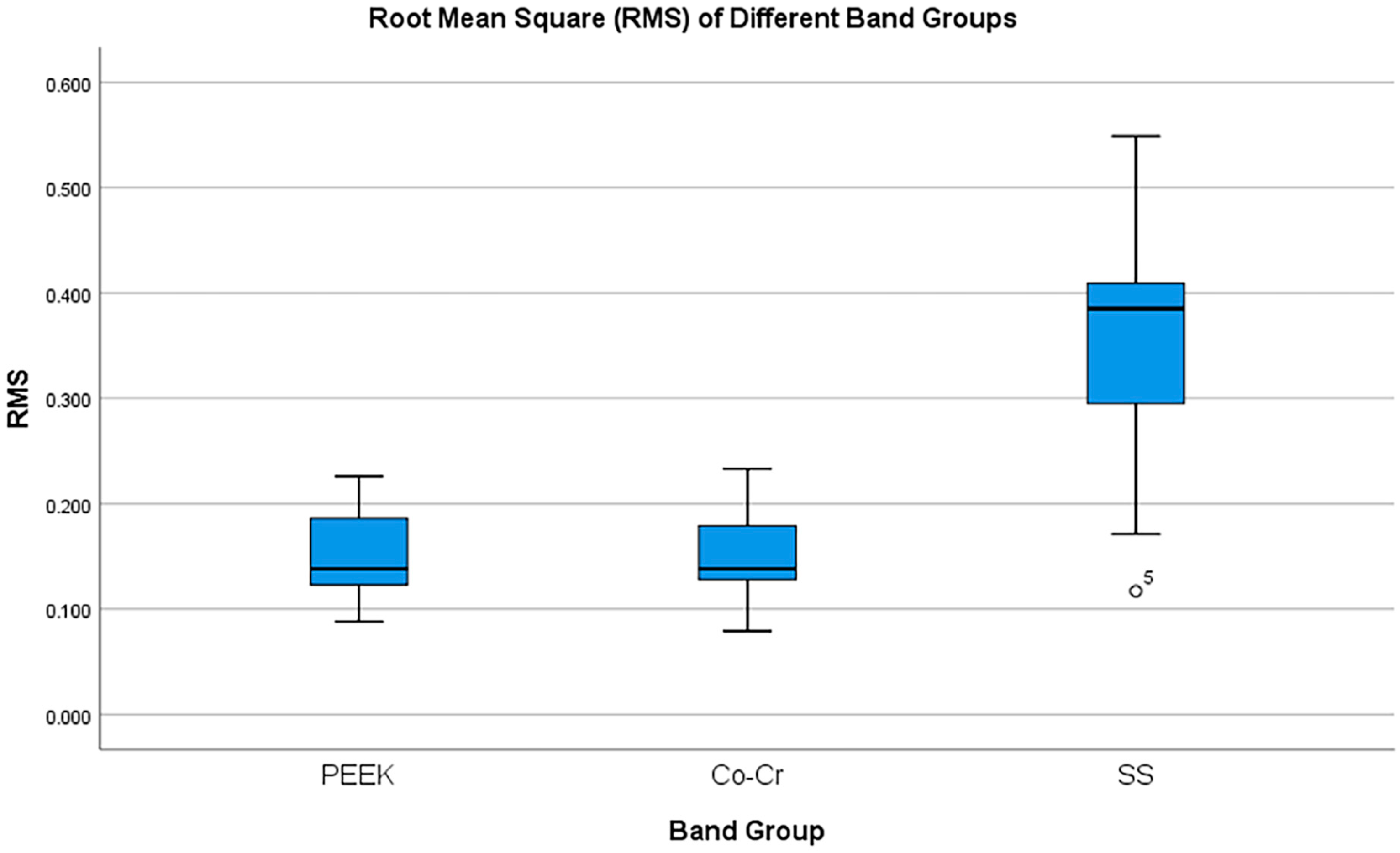

3.1. Fit Accuracy Test

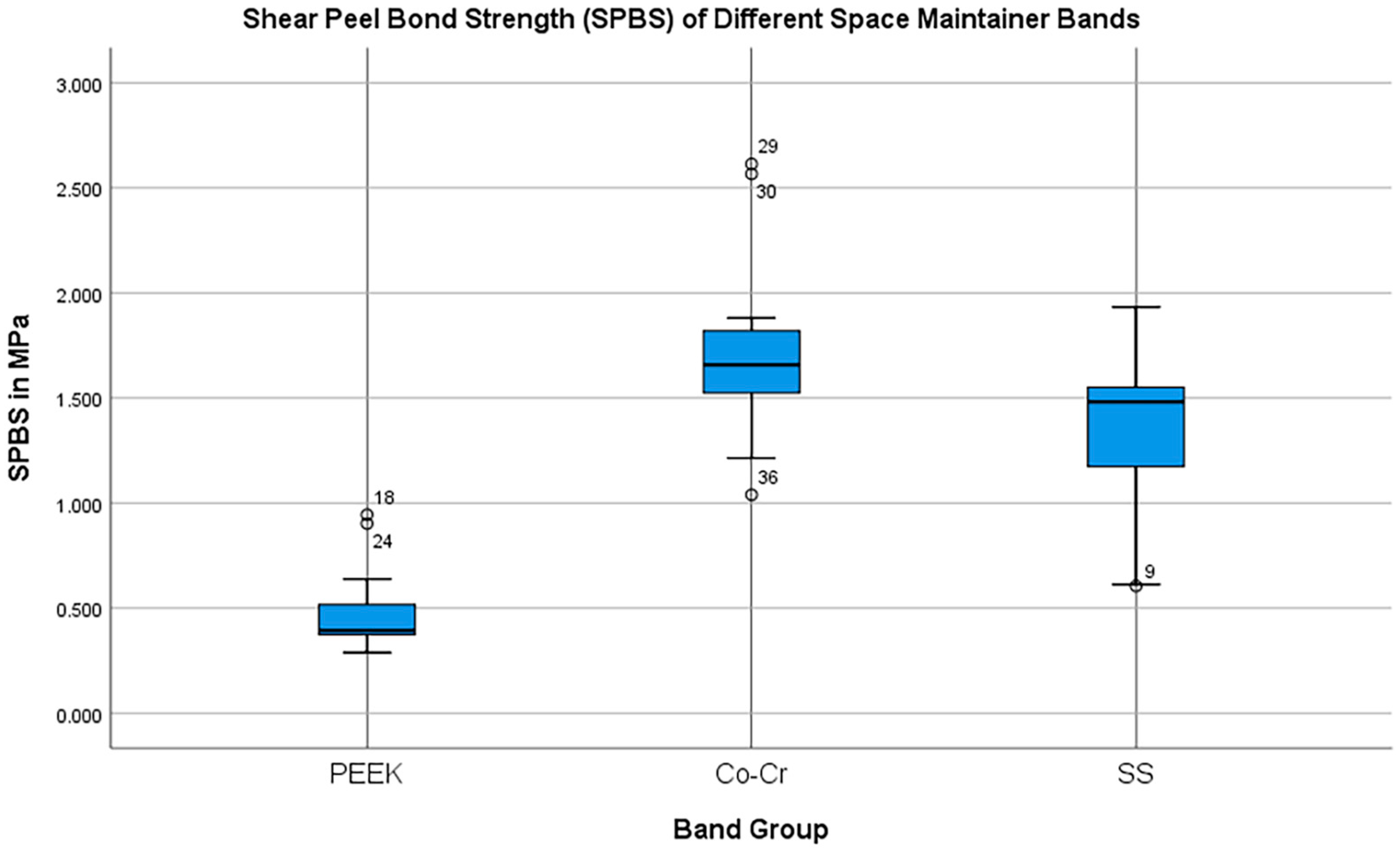

3.2. SPBS

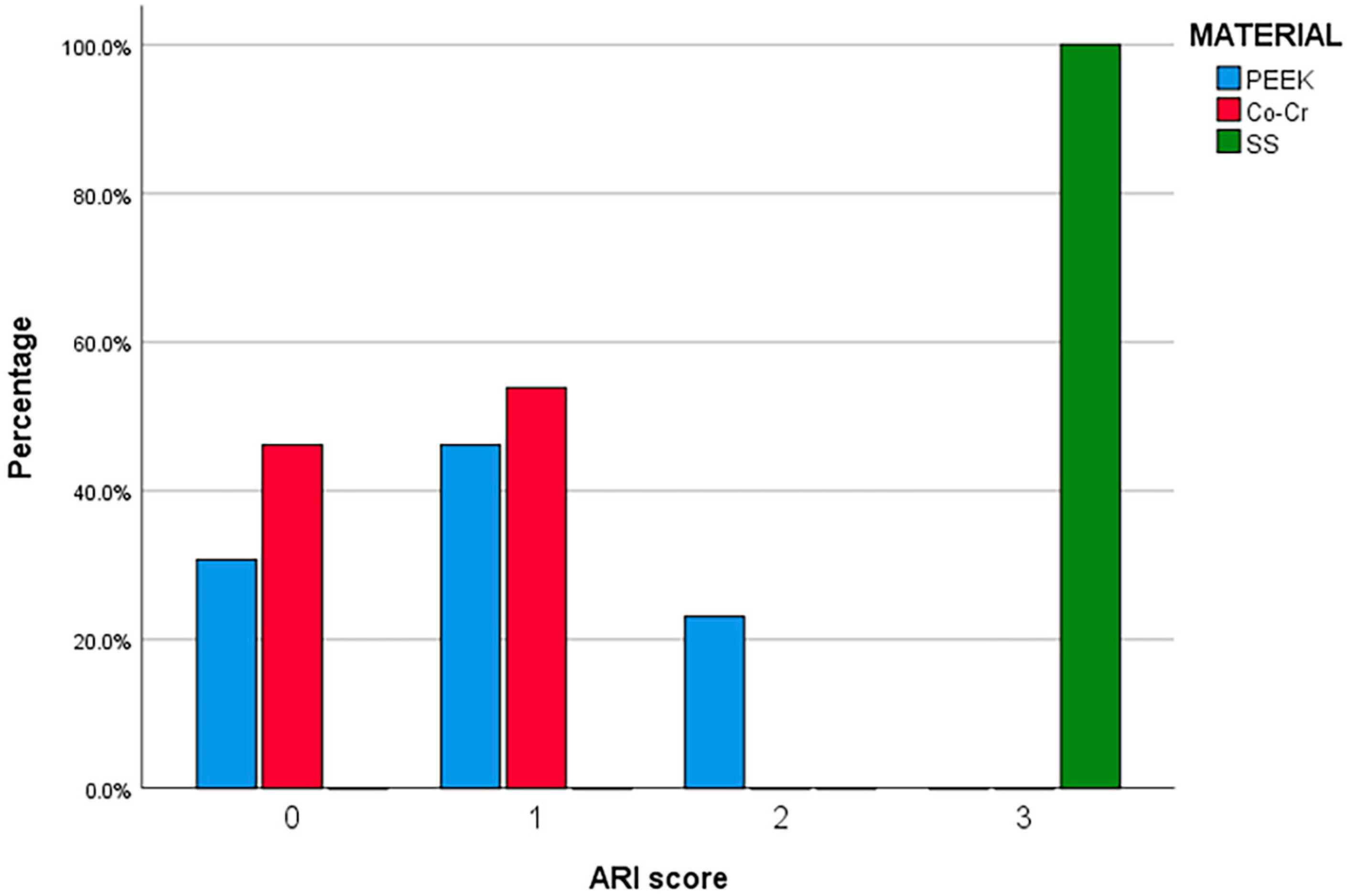

3.3. ARI Grade Distribution

4. Discussion

4.1. Fit Accuracy

4.2. Shear Peel Bond Strength

4.2.1. Clinical Significance

4.2.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Computer-aided design |

| CAM | Computer-aided manufacturing |

| PEEK | Polyetheretherketone |

| Co-Cr | Cobalt–chromium |

| SS | Stainless steel |

| SPBS | Shear peel bond strength |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| ARI | Adhesive remnant index |

| STL | Standard tessellation language |

| ICP | Iterative closest point |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

References

- Watt, E.; Ahmad, A.; Adamji, R.; Katsimpali, A.; Ashley, P.; Noar, J. Space maintainers in the primary and mixed dentition—A clinical guide. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 225, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, S.; Rao, D.; Panwar, S.; Pawar, B.; Ameen, S. 3D Printed Band and Loop Space Maintainer: A Digital Game Changer in Preventive Orthodontics. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 45, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburrino, F.; Chiocca, A.; Aruanno, B.; Paoli, A.; Lardani, L.; Carli, E.; Derchi, G.; Giuca, M.R.; Razionale, A.V.; Barone, S. A Novel Digitized Method for the Design and Additive Manufacturing of Orthodontic Space Maintainers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illescas, G.C.J.; García, K.G.U.; Picón, M.Y.Y.; Illescas, G.C.J.; García, K.G.U.; Picón, M.Y.Y. Innovation in interceptive orthodontics: Digital space maintainers with CAD/CAM and 3D printing: Bibliographic review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, A.; Karayilmaz, H. Comparative evaluation of the clinical success of 3D-printed space maintainers and band–loop space maintainers. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 34, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, K.G.U.; Altun, A.C.; Kırzıoğlu, Z. In vitro evaluation of onlay restorations on primary teeth. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2017, 40, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Torres, C.; Gomes-Silva, J.; Chinelatti, M.; Menezes, F.; Palma-Dibb, R.; Borsatto, M.C. Microstructure and Mineral Composition of Dental Enamel of Permanent and Deciduous Teeth. Microsc. Res. Technol. 2009, 73, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.L.; Cavalheiro, C.P.; Gimenez, T.; Imparato, J.C.P.; Bussadori, S.K.; Lenzi, T.L. Bonding Performance of Universal and Contemporary Adhesives in Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Studies. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 43, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danevitch, N.; Frankenberger, R.; Lücker, S.; Gärtner, U.; Krämer, N. Dentin Bonding Performance of Universal Adhesives in Primary Teeth In Vitro. Materials 2023, 16, 5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuc, M.; Yilmaz, H. Comparison of fit accuracy between conventional and CAD/CAM-fabricated band-loop space maintainers. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekow, E.D. Dental CAD/CAM systems: A 20-year success story. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2006, 137, 5S–6S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, H.K. Application of CAD-CAM for Fabrication of Metal-Free Band and Loop Space Maintainer. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZD14–ZD16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.; Bhardwaj, A.; Luke, A.M.; Wahjuningrum, D.A. Effectiveness of traditional band and loop space maintainer vs 3D-printed space maintainer following the loss of primary teeth: A randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Morita, K.; Nishio, F.; Abekura, H.; Tsuga, K. Clinical report of six-month follow-up after cementing PEEK crown on molars. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, L.; Figueiral, M.H.; Neves, C.B.; Malheiro, R.; Sampaio-Fernandes, M.A.; Oliveira, S.J.; Sampaio-Fernandes, M.M. Fit Accuracy of Cobalt–Chromium and Polyether Ether Ketone Prosthetic Frameworks Produced Using Digital Techniques: In Vitro Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, A.; Sadana, G.; Mehra, M.; Mahajan, M. Evaluation of Shear Peel Bond Strength of Different Adhesive Cements Used for Fixed Space Maintainer Cementation: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 14, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñate, L.; Basilio, J.; Roig, M.; Mercadé, M. Comparative study of interim materials for direct fixed dental prostheses and their fabrication with CAD/CAM technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassary Zadeh, P.; Lümkemann, N.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B.; Kollmuss, M. Differences in Radiopacity, Surface Properties, and Plaque Accumulation for CAD/CAM-Fabricated vs Conventionally Processed Polymer-based Temporary Materials. Oper. Dent. 2019, 45, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, L.; Rajesh, A.; Justin, R.M.; Paranthaman, H.; Varghese, R.P. Effect of Salivary Contamination on the Bond Strength of Total-etch and Self-etch Adhesive Systems: An in vitro Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulazeez, M.I.; Majeed, M.A. Fracture Strength of Monolithic Zirconia Crowns with Modified Vertical Preparation: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 16, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Vo, J.; Abubakr, N.H. Shear Bond Strength of Different Types of Cement Used for Bonding Band and Loop Space Maintainer. Open J. Stomatol. 2023, 13, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.S.; Karawia, I.; Gaber, A.H.; Hall, M.A. Evaluation of the Shear Peel Bond Strength of the Computer-aided Design/Computer-aided Manufacturing Polyetheretherketone Band for Space Maintainer: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2025, 18, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhafiz, S.H.; Abdelkader, S.H.; Azer, A. Marginal and internal fit evaluation of metal copings fabricated by selective laser sintering and CAD/CAM milling techniques: In-vitro study. Alex. Dent. J. 2022, 47, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Wismeijer, D.; Osman, R. Additive Manufacturing Techniques in Prosthodontics: Where Do We Currently Stand? A Critical Review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Banaa, L.R. Evaluation of microleakage for three types of light cure orthodontic band cement. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2022, 12, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, N.A.; Parkhedkar, R.D. An evaluation of dimensional accuracy of one-step and two-step impression technique using addition silicone impression material: An in vitro study. J. Indian. Prosthodont. Soc. 2013, 13, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, S.J.; El-Hammali, H.; Morgano, S.M.; Elkassaby, H. Evaluation of the accuracy of 2 digital intraoral scanners: A 3D analysis study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarauz, C.; Pradíes, G.J.; Chebib, N.; Dönmez, M.B.; Karasan, D.; Sailer, I. Influence of age, training, intraoral scanner, and software version on the scan accuracy of inexperienced operators. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.B.; Wismeijer, D. Factors Influencing the Dimensional Accuracy of 3D-Printed Full-Coverage Dental Restorations Using Stereolithography Technology. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 29, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, O.; Watts, D.C.; Sigusch, B.W.; Kuepper, H.; Guentsch, A. Marginal and internal fit of pressed lithium disilicate partial crowns in vitro: A three-dimensional analysis of accuracy and reproducibility. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AboulAzm, N.; Sharaf, A.; Dowidar, K.; AbdelHakim, A. Effectiveness of CAD/CAM peek fabricated space maintainer in children: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Alex. Dent. J. 2023, 48, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantekin, K.; Delikan, E.; Cetin, S. In vitro bond strength and fatigue stress test evaluation of different adhesive cements used for fixed space maintainer cementation. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Gopikrishna, V.; Datta, M. CRIS Guidelines (Checklist for Reporting In-vitro Studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting in-vitro studies in experimental dental research. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrepois, M.; Soenen, A.; Bartala, M.; Laviole, O. Marginal adaptation of ceramic crowns: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 110, 447–454.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.C.; Henriques, G.E.P.; Sobrinho, L.C.; de Góes, M.F. Stress-relieving and porcelain firing cycle influence on marginal fit of commercially pure titanium and titanium-aluminum-vanadium copings. Dent. Mater. 2003, 19, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, P.H.O.; do Valle, A.L.; de Carvalho, R.M.; De Goes, M.F.; Pegoraro, L.F. Correlation between margin fit and microleakage in complete crowns cemented with three luting agents. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2008, 16, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molin, M.K.; Karlsson, S.L. A randomized 5-year clinical evaluation of 3 ceramic inlay systems. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2000, 13, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tribst, J.P.M.; dos Santos, A.F.C.; da Cruz Santos, G.; da Silva Leite, L.S.; Lozada, J.C.; Silva-Concílio, L.R.; Baroudi, K.; Amaral, M. Effect of Cement Layer Thickness on the Immediate and Long-Term Bond Strength and Residual Stress between Lithium Disilicate Glass-Ceramic and Human Dentin. Materials 2021, 14, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, T.; Ramoglu, S.I.; Ertas, H.; Ulker, M. Microleakage of orthodontic band cement at the cement-enamel and cement-band interfaces. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Computer-aided design of polyetheretherketone for application to removable pediatric space maintainers. BMC Oral. Health. 2020, 20, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.A. Maintenance of space by innovative three-dimensional-printed band and loop space maintainer. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2019, 37, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.H.; Xiong, H.C.; Chen, K. Comparative evaluation of esthetic and physical properties of CAD/CAM PEEK oral space maintainers. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2025, 23, 22808000251345581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.O.; Tsitrou, E.A.; Pollington, S. Comparative in vitro evaluation of CAD/CAM vs conventional provisional crowns. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2016, 24, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, E.E.; Aboutaleb, F.A.; Alam-Eldein, A.M. Virtual Evaluation of the Accuracy of Fit and Trueness in Maxillary Poly(etheretherketone) Removable Partial Denture Frameworks Fabricated by Direct and Indirect CAD/CAM Techniques. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, X.; Wang, G.; Kang, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y. A Novel Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Assisted Manufacture Method for One-Piece Removable Partial Denture and Evaluation of Fit. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Hey, J.; Schweyen, R.; Setz, J.M. Accuracy of CAD-CAM-fabricated removable partial dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barraclough, O.; Gray, D.; Ali, Z.; Nattress, B. Modern partial dentures—Part 1: Novel manufacturing techniques. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boitelle, P.; Mawussi, B.; Tapie, L.; Fromentin, O. A systematic review of CAD/CAM fit restoration evaluations. J. Oral Rehabil. 2014, 41, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadioti, E.; Aquilino, S.A.; Gratton, D.G.; Holloway, J.A.; Denry, I.; Thomas, G.W.; Qian, F. 3D and 2D marginal fit of pressed and CAD/CAM lithium disilicate crowns made from digital and conventional impressions. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.; Valcanaia, A.; Neiva, G.; Mehl, A.; Fasbinder, D. Digital evaluation of the fit of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate crowns with a new three-dimensional approach. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, F.D.; Prado, C.J.; Prudente, M.S.; Carneiro, T.A.P.N.; Zancopé, K.; Davi, L.R.; Mendonça, G.; Cooper, L.F.; Soares, C.J. Micro-computed tomography evaluation of marginal fit of lithium disilicate crowns fabricated by using chairside CAD/CAM systems or the heat-pressing technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Vogler, J.A.H.; Schmidt, A.; Rehmann, P.; Wöstmann, B. Chairside measurement of the marginal and internal fit of crowns: A new intraoral scan-based approach. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 2459–2468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Persson, A.S.K.; Andersson, M.; Odén, A.; Sandborgh-Englund, G. Computer aided analysis of digitized dental stone replicas by dental CAD/CAM technology. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.M.; Kim, S.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, W.C. Trueness of milled prostheses according to number of ball-end mill burs. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H. Digital approach to assessing the 3-dimensional misfit of fixed dental prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.N.; Lee, K.E.; Lee, K.B.; Jeong, S.M.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, C.-H.; An, S.-Y.; Lee, D.-H. Verification of a computer-aided replica technique for evaluating prosthesis adaptation using statistical agreement analysis. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H.; Hatakeyama, W.; Komine, F.; Takafuji, K.; Takahashi, T.; Yokota, J.; Oriso, K.; Kondo, H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groten, M.; Axmann, D.; Pröbster, L.; Weber, H. Determination of the minimum number of marginal gap measurements required for practical in vitro testing. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.S.; Rodrigues, A.C.C.; Chaves, E.T.; Susin, A.H.; Valandro, L.F.; Pereira, G.K.R.; Rippe, M.P. Surface Treatments and Adhesives Used to Increase the Bond Strength Between Polyetheretherketone and Resin-based Dental Materials: A Scoping Review. J. Adhes. Dent. 2022, 24, b2288283. [Google Scholar]

- Alabbadi, A.A.; Abdalla, E.M.; Hanafy, S.A.; Yousry, T.N. A comparative study of CAD/CAM fabricated polyether ether ketone and fiber-glass reinforcement composites versus metal lingual retainers under vertical load (an in vitro study). BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qudeimat, M.A.; Sasa, I.S. Clinical success and longevity of band and loop compared to crown and loop space maintainers. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, B.; Fabris, D.; Mesquita-Guimarães, J.; Sousa, A.C.; Hammes, N.; Souza, J.C.M.; Silva, F.S.; Fredel, M.C. Influence of laser structuring of PEEK, PEEK-GF30 and PEEK-CF30 surfaces on the shear bond strength to a resin cement. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciafesta, V.; Sfondrini, M.F.; Baluga, L.; Scribante, A.; Klersy, C. Use of a self-etching primer in combination with a resin-modified glass ionomer: Effect of water and saliva contamination on shear bond strength. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 124, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQhtani, F.A.B.A.; Abdulla, A.M.; Kamran, M.A.; Luddin, N.; Abdelrahim, R.K.; Samran, A.; AlJefri, G.H.; Niazi, F.H. Effect of adding sodium fluoride and nano-hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to the universal adhesive on bond strength and microleakage on caries-affected primary molars. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

| Tested Properties | Groups | Mean | SD | 95% Cl [Lower, Upper] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit accuracy (mm) | PEEK | 0.152 a | 0.045 | [0.124, 0.179] | |

| Co-Cr | 0.151 a | 0.047 | [0.122, 0.179] | ||

| SS | 0.344 b | 0.118 | [0.272, 0.415] | ||

| Median (MPa) | IQR (25–75%) | Min–Max | |||

| Shear peel bond strength (MPa) | PEEK | 0.393 b | 0.288–0.507 | 0.288–0.944 | |

| Co-Cr | 1.657 a | 1.330–1.657 | 1.039–2.613 | ||

| SS | 1.481 a | 1.109–1.730 | 0.605–1.932 | ||

| ARI grading | ARI | PEEK | Co-Cr | SS | Total |

| 0 | 3 (23.1%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 | |

| 1 | 6 (46.1%) | 7 (53.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 | |

| 2 | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 | |

| 3 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (100.0%) | 13 | |

| Total | 13 | 13 | 13 | 39 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, M.K.; Rauf, A.M. Fit Accuracy and Shear Peel Bond Strength of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Versus Conventional Stainless Steel Space Maintainers: In Vitro Comparative Study. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060159

Ahmed MK, Rauf AM. Fit Accuracy and Shear Peel Bond Strength of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Versus Conventional Stainless Steel Space Maintainers: In Vitro Comparative Study. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060159

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Marzia Kareem, and Aras Maruf Rauf. 2025. "Fit Accuracy and Shear Peel Bond Strength of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Versus Conventional Stainless Steel Space Maintainers: In Vitro Comparative Study" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060159

APA StyleAhmed, M. K., & Rauf, A. M. (2025). Fit Accuracy and Shear Peel Bond Strength of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Versus Conventional Stainless Steel Space Maintainers: In Vitro Comparative Study. Prosthesis, 7(6), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060159