Effect of Post-Casting Cooling Rate on Clasp Complications in Co–Cr–Mo Removable Partial Dentures: 5-Year Retrospective Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Room temperature air cooling (RATA): This type of cooling is performed in daily practice in dental laboratories. After casting the alloy, the flask is left to cool in room air until the bright red color of the alloy disappears. Alloy manufacturers then recommend immersion in cold water to prevent a continuous arrangement of carbides along the grain contours. Carbides, being the last to solidify, tend to settle at the edges, reducing strength and plasticity.

- -

- Slow furnace cooling (LRF): This type of cooling, first explored in 2004, is used at the dentist’s request. Once the alloy has been cast, the flask is left to cool slowly for 24 h in a furnace (model WARMY 9, Manfredi), heated to 980°C (1980°F), and then turned off, leaving the door open approximately 5 cm (2 in). This type of cooling allows the atoms to rearrange into a more stable and homogeneous crystalline structure, helping prevent the formation of internal stresses, structural defects, and precipitation of unwanted phases along grain boundaries. It effectively increases the mechanical properties while maintaining good ductility.

Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CK | Kennedy class |

| RPD | Removable partial denture |

| LRF | Slow cooling in the oven |

| RATA | Air cooling at room temperature |

References

- Kim, J.J. Revisiting the Removable Partial Denture. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behr, M.; Zeman, F.; Passauer, T.; Koller, M.; Hahnel, S.; Buergers, R.; Lang, R.; Handel, G.; Kolbeck, C. Clinical performance of cast clasp-retained removable partial dentures: A retrospective study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2012, 25, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhamoudi, F.H.; Aldosari, L.I.N.; Alshadidi, A.A.F.; Bin Hassan, S.A.; Alwadi, M.A.M.; Vaddamanu, S.K.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. An Investigation of the Fracture Loads Involved in the Framework of Removable Partial Dentures Using Two Types of All-Ceramic Restorations. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ceraulo, S.; Caccianiga, P.; Barbarisi, A.; Caccianiga, G.; Biagi, R. Insertion axis in removable prosthesis: A preliminary report. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2024, 73, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, P.; Moumni, Z.; Zhang, W. Effects of Build Direction and Heat Treatment on the Defect Characterization and Fatigue Properties of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Ti6Al4V. Aerospace 2024, 11, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Kakitani, R.; Cangerana, K.C.B.; Garcia, A.; Cheung, N. Microstructural Refinement and Improvement of Microhardness of a Hypoeutectic Al–Fe Alloy Treated by Laser Surface Remelting. Mater. Proc. 2020, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawid, M.-T.; Moldovan, O.; Rudolph, H.; Kuhn, K.; Luthardt, R.G. Technical Complications of Removable Partial Dentures in the Moderately Reduced Dentition: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandman, E. The influence of different heat treatments on a dental Co-Cr alloy. Odontol. Revy. 1976, 27, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ko, K.-H.; Kang, H.-G.; Huh, Y.-H.; Park, C.-J.; Cho, L.-R. Effects of heat treatment on the microstructure, residual stress, and mechanical properties of Co-Cr alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126, 105051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktürk, D.; Yildiz, M.T.; Yurtkuran, E.; Babacan, N. Microstructural and fatigue properties of dental structures produced via selective laser melting: Comparing Co-Cr-Mo, Co-Cr-Mo-W and Co-Cr-W alloys. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, F.; Song, M.; Ni, S.; Liu, S. Evoluzionedellamicrostruttura, trasformazionedella martensite e proprietàmeccanichedelleleghe Co-Cr-Mo-W trattatetermicamentemediantefusione laser selettiva. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 113, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, W.; Alapati, S.B. Heat Treatment of Dental Alloys: A Review. In Metallurgy—Advances in Materials and Processes; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Du, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Yi, Y. Effects of rapid infrared radiation heating on the warping deformation and mechanical properties of selective laser melted Co-Cr dental alloy. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 907.e1–907.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-J.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, H.-I.; Kwon, Y.H.; Seol, H.-J. Effect of ice-quenching after oxidation treatment on hardening of a Pd-Cu-Ga-Zn alloy for bonding porcelain. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 79, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Mori, M.; Chiba, A. Assessment of precipitation behavior in dental castings of a Co-Cr-Mo alloy. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 50, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Marcos, C.; Mirza-Rosca, J.C.; Vermesan, D.; Saceleanu, A. Evaluation of the Structure, Microhardness and Corrosion Properties of Cobalt-chromium Dental Alloys with Two Different Cooling Media. Int. J. Met. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htat, H.L.; Takaichi, A.; Kajima, Y.; Kittikundecha, N.; Kamijo, S.; Hanawa, T.; Wakabayashi, N. Influence of stress-relieving heat treatments on the efficacy of Co-Cr-Mo-W alloy copings fabricated using selective laser melting. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, M.T.; Babacan, N. Comparison of tensile properties and porcelain bond strength in metal frameworks fabricated by selective laser melting using three different Co-Cr alloy powders. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, L.; Toni, G.; Stefanoni, F.; Mollica, F.; Guarneri, M.P.; Siciliani, G. The effect of temperature on the mechanical behavior of nickel-titanium orthodontic initial archwires. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vutova, K.; Stefanova, V.; Markov, M.; Vassileva, V. Study on Hardness of Heat-Treated CoCrMo Alloy Recycled by Electron Beam Melting. Materials 2023, 16, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajima, Y.; Takaichi, A.; Kittikundecha, N.; Nakamoto, T.; Kimura, T.; Nomura, N.; Kawasaki, A.; Hanawa, T.; Takahashi, H.; Wakabayashi, N. Effect of heat-treatment temperature on microstructures and mechanical properties of Co–Cr–Mo alloys fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 726, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceraulo, S.; Buzzanca, R.; Geraci, D.; Passi, P. Variazionedellaresistenza a trazione e compressione di unastellite con diversimetodi di raffreddamento. Protech Anno. 2004, 5, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, A.; Ben-Ur, Z. The mandibular first premolar as an abutment for distal-extension removable partial dentures: A modified clasp assembly design. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 188, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G.; Herford, A.S.; Lauritano, F.; D’Amico, C.; Lo Giudice, R.; Laino, L.; Troiano, G.; Crimi, S.; Cicciù, M. Interferon Crevicular Fluid Profile and Correlation with Periodontal Disease and Wound Healing: A Systemic Review of Recent Data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Curinga, M.R.S.; da Silva, D.J.; Pereira, A.L.C.; da Silva, N.R.; Carreiro, A.F.P. Digital planning and surveying for a rotational path removable partial denture: A case report. Gen. Dent. 2024, 72, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schittly, J. Détermination de l’axed’insertion et impératifsesthétiquesenprothèseadjointepartielle [Determination of the axis of insertion and the esthetic requirements of removable partial dentures]. Rev. Odontostomatol. 1985, 14, 293–298. (In French) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ceraulo, S. Vertical dimension modification. Case report [Modifica della dimensione verticale. Caso clinico]. PROTECH 2008, 9, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkoum, M.A. New Clasp Assembly for Distal Extension Removable Partial Dentures: The Reverse RPA Clasp. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renani, M.S.; Meysami, A.; Najafabadi, R.A.; Meysami, M.; Khodaei, M. Effect of Cooling Rate on Structural, Corrosion, and Mechanical Properties of Cobalt–Chromium–Molybdenum Dental Alloys. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2024, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittikundecha, N.; Kajima, Y.; Takaichi, A.; Cho, H.H.W.; Htat, H.L.; Doi, H.; Takahashi, H.; Hanawa, T.; Wakabayashi, N. Fatigue properties of removable partial denture clasps fabricated by selective laser melting followed by heat treatment. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 98, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

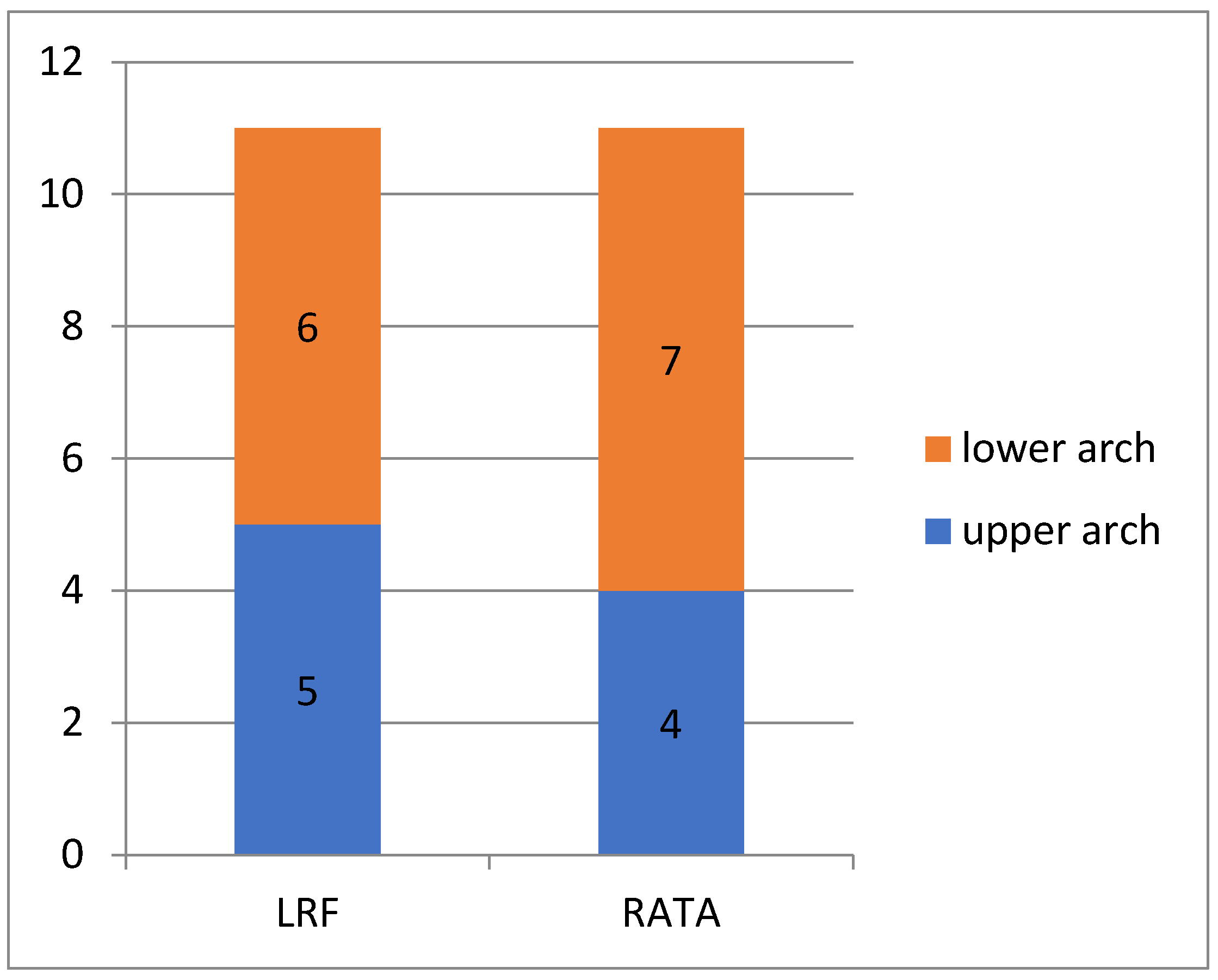

| Prosthesis | Superior | Inferior | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow cooling in the oven | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| % upper/lower | 45.45% | 54.54% | |

| Kennedy Class (CK) | 1 (I CK—20%) | 3 (I CK—50%) | 4 |

| 3 (II CK—60%) | 3 (II CK—50%) | 6 | |

| 1 (III CK—20%) | _ | 1 | |

| Air cooling at room temperature | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| % upper/lower | 36.36% | 63.63% | |

| Kennedy Class (CK) | 1 (I CK—25%) | 1 (I CK—14.28%) | 2 |

| 1 (II CK—25%) | 1 (II CK—14.28%) | 2 | |

| 2 (III CK—50%) | 5 (III CK—71.42%) | 7 |

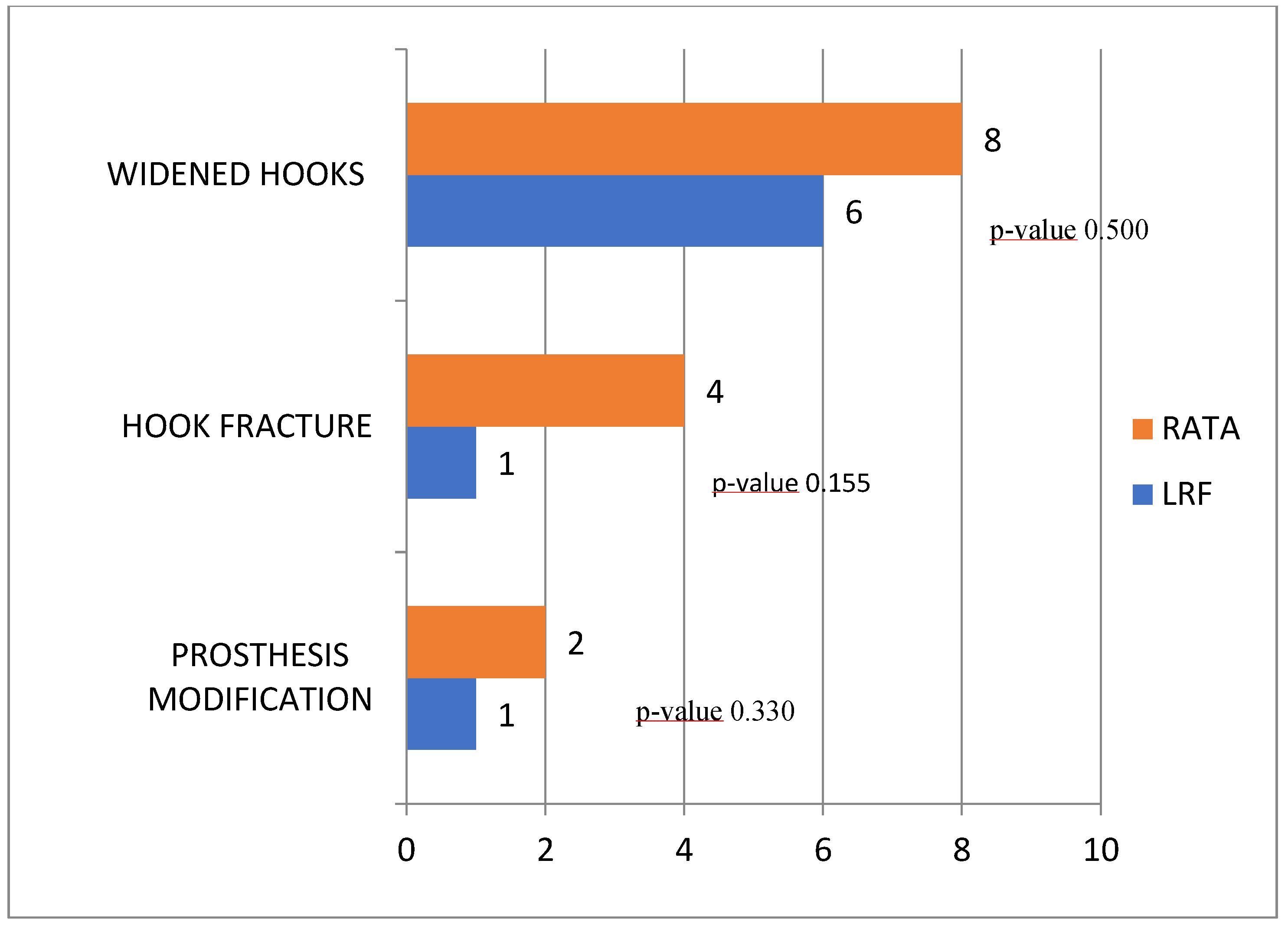

| 11 RPD LRF | LRF | 11 RPD RATA | RATA | OddS RATIO | 95% IC | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modification Prosthesis | 1 | 9.1% | 2 | 18.2% | 0.44 | 0.03–6.20 | 0.500 |

| Fractured clasp | 1 | 9.1% | 4 | 36.4% | 0.18 | 0.02–1.92 | 0.155 |

| Enlarged clasp | 6 | 54.4% | 8 | 72.7% | 0.43 | 0.08–2.31 | 0.330 |

| Source of Bias | Type of Bias | Description of the Bias | Potential Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness of the clasps intentionally | Confounding variable | The LRF group hooks were designed to be thinner (2/3 tenths of a millimeter) in order to improve aesthetics, unlike the RATA group hooks. This approach was part of a manufacturing protocol aimed at testing whether the improved mechanical properties of the LRF allowed for a reduction in thickness without compromising strength. | This difference in thickness introduces a confounding variable that makes it impossible to isolate the effect of the cooling method alone. The observed differences in failure rates could be attributed to both thickness variations and the cooling method. Consequently, this study compares not just two cooling methods, but two different manufacturing protocols. |

| Retrospective nature of follow up | Information bias | The analysis is based on clinical data collected retrospectively over a 5-year period. The records may not be standardized or sufficiently detailed regarding patient behavioral factors, such as diet or maintenance efforts. | The lack of quantitative and standardized data on factors such as diet or actual grooming effort prevents us from establishing a causal relationship between these behaviors and hook failures. Conclusions may be influenced by unmeasured variables. |

| Small sample | Sampling bias | The total number of prostheses analyzed (n=22) is limited, with only 11 for each group | A small sample size reduces the statistical power of the study, making it difficult to detect significant differences between groups. |

| Operator variability | Experimental design | The RPDs were designed, manufactured, and evaluated after 5 years by the same experienced dental technician. Furthermore, the evaluation of the clasps was conducted blindly, eliminating measurement bias. | The evaluation with a single expert and blinded operator significantly reduces the risk of bias related to the operator’s subjectivity, strengthening the internal validity of the study. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ceraulo, S.; Caccianiga, G.; Lauritano, D.; Carinci, F. Effect of Post-Casting Cooling Rate on Clasp Complications in Co–Cr–Mo Removable Partial Dentures: 5-Year Retrospective Data. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060137

Ceraulo S, Caccianiga G, Lauritano D, Carinci F. Effect of Post-Casting Cooling Rate on Clasp Complications in Co–Cr–Mo Removable Partial Dentures: 5-Year Retrospective Data. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060137

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeraulo, Saverio, Gianluigi Caccianiga, Dorina Lauritano, and Francesco Carinci. 2025. "Effect of Post-Casting Cooling Rate on Clasp Complications in Co–Cr–Mo Removable Partial Dentures: 5-Year Retrospective Data" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060137

APA StyleCeraulo, S., Caccianiga, G., Lauritano, D., & Carinci, F. (2025). Effect of Post-Casting Cooling Rate on Clasp Complications in Co–Cr–Mo Removable Partial Dentures: 5-Year Retrospective Data. Prosthesis, 7(6), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060137