Enhancing the Antibacterial and Biointegrative Properties of Microporous Titanium Surfaces Using Various Metal Coatings: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

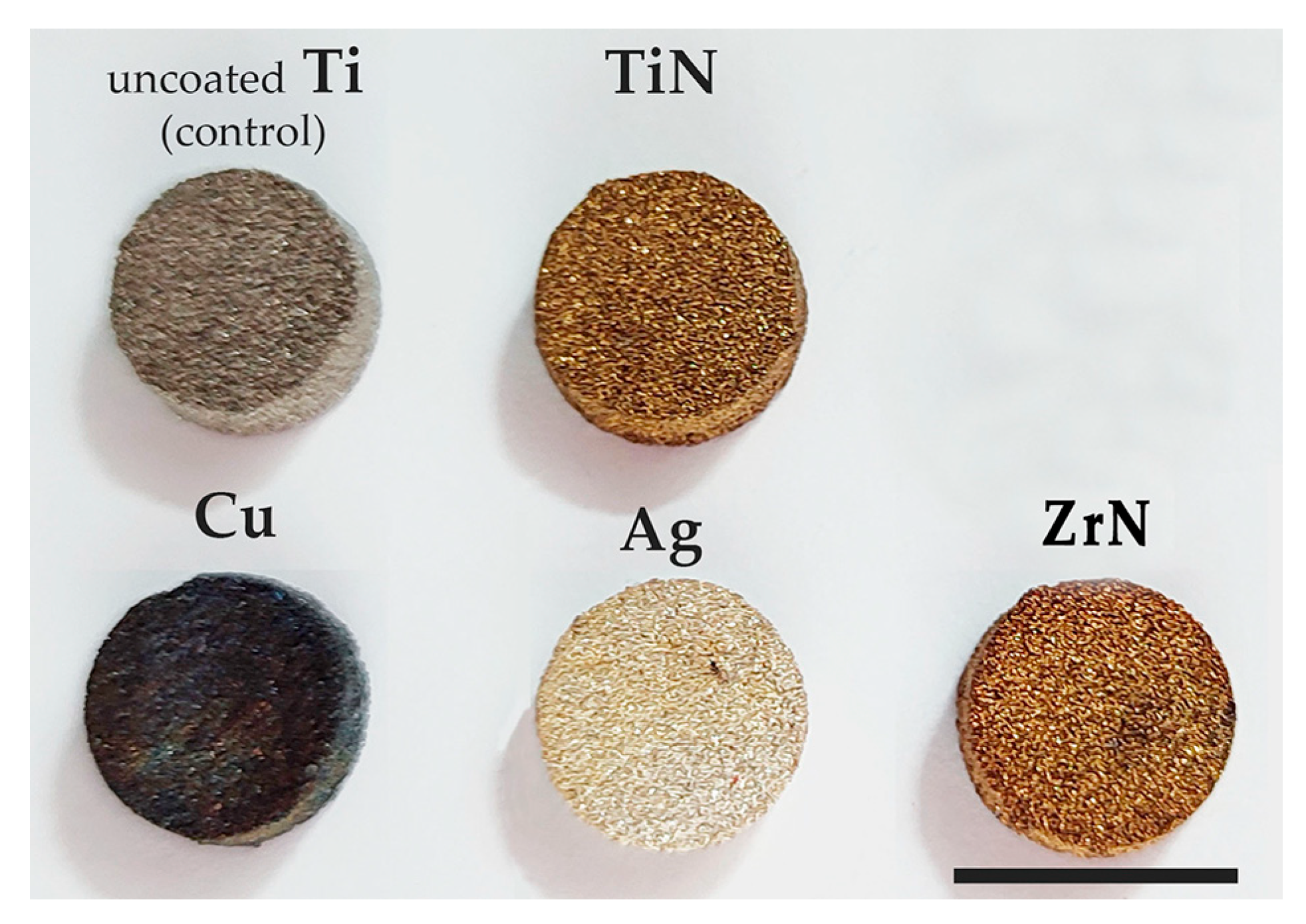

2.1. Synthesis, Metal Coating, and Characterization of the Ti Disks

2.1.1. Porous Titanium Samples for the Current Study

- Once the 10−5 torr vacuum was achieved, the chamber was back-filled with high-purity argon to partial pressure between 11 psi and 12 psi. The sintering (that involved decomposition of titanium hydride to pure titanium) was carried out at 1190 °C (2174 °F) for 2 h.

- For the second stage of sintering, the vacuum pressure was reduced to 10−5 torr (no argon), and the temperature was raised to 1300 °C (2372 °F). The sintering time was 4 h.

2.1.2. Coating of the Samples (Figure 2)

2.2. Cells

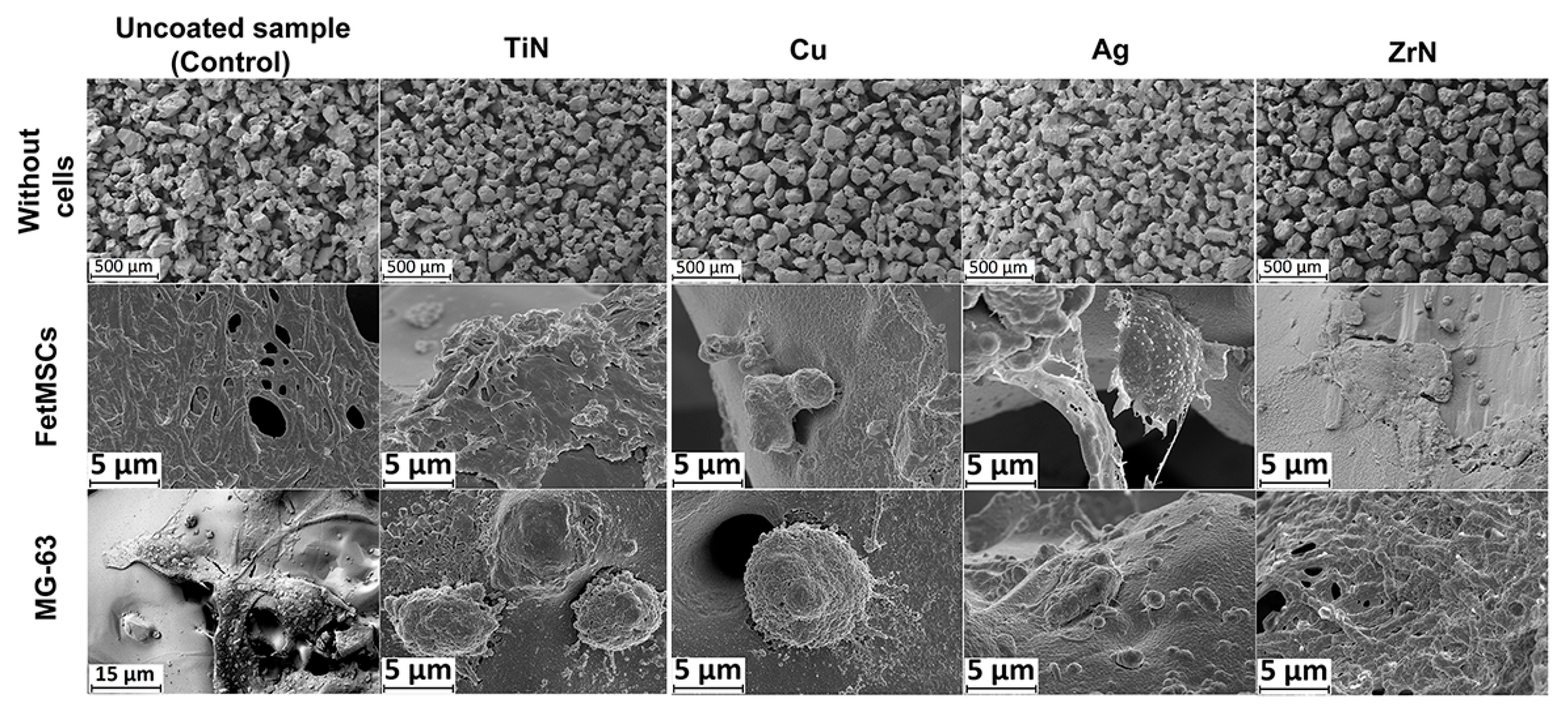

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

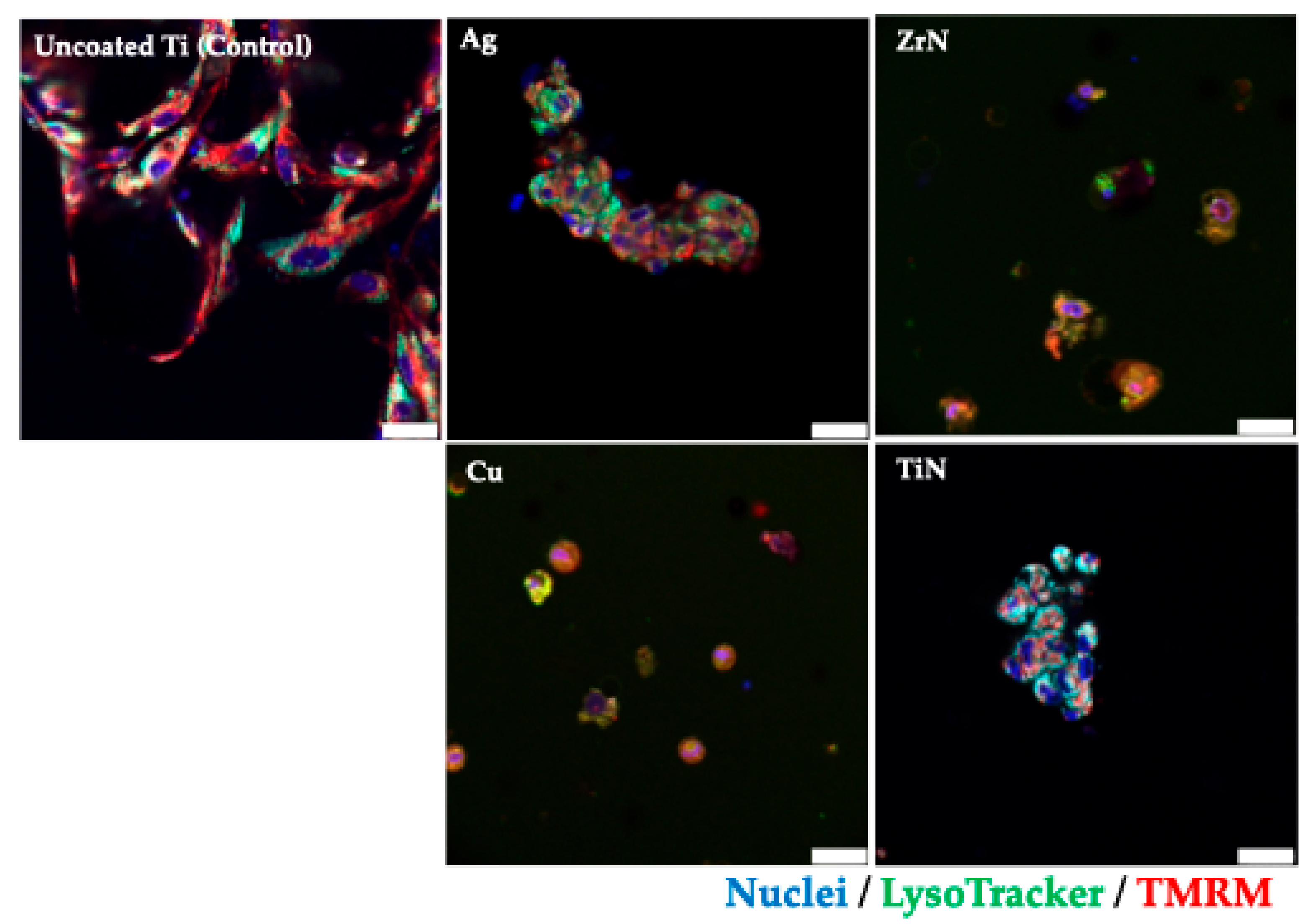

2.4. Confocal Microscopy

2.5. Testing of Antibacterial Activities

2.6. Analysis of the Matrix Metalloproteinase Production

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

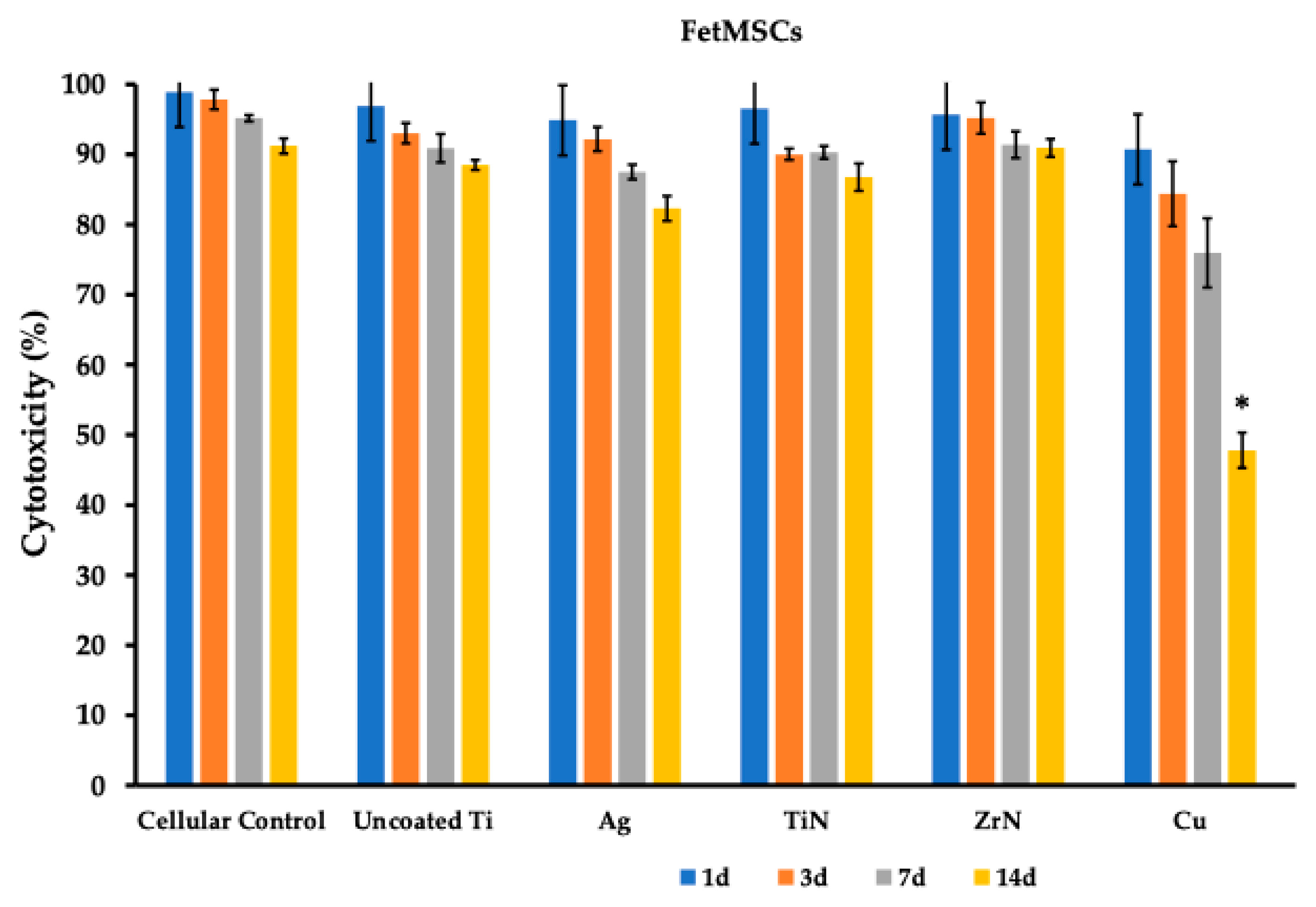

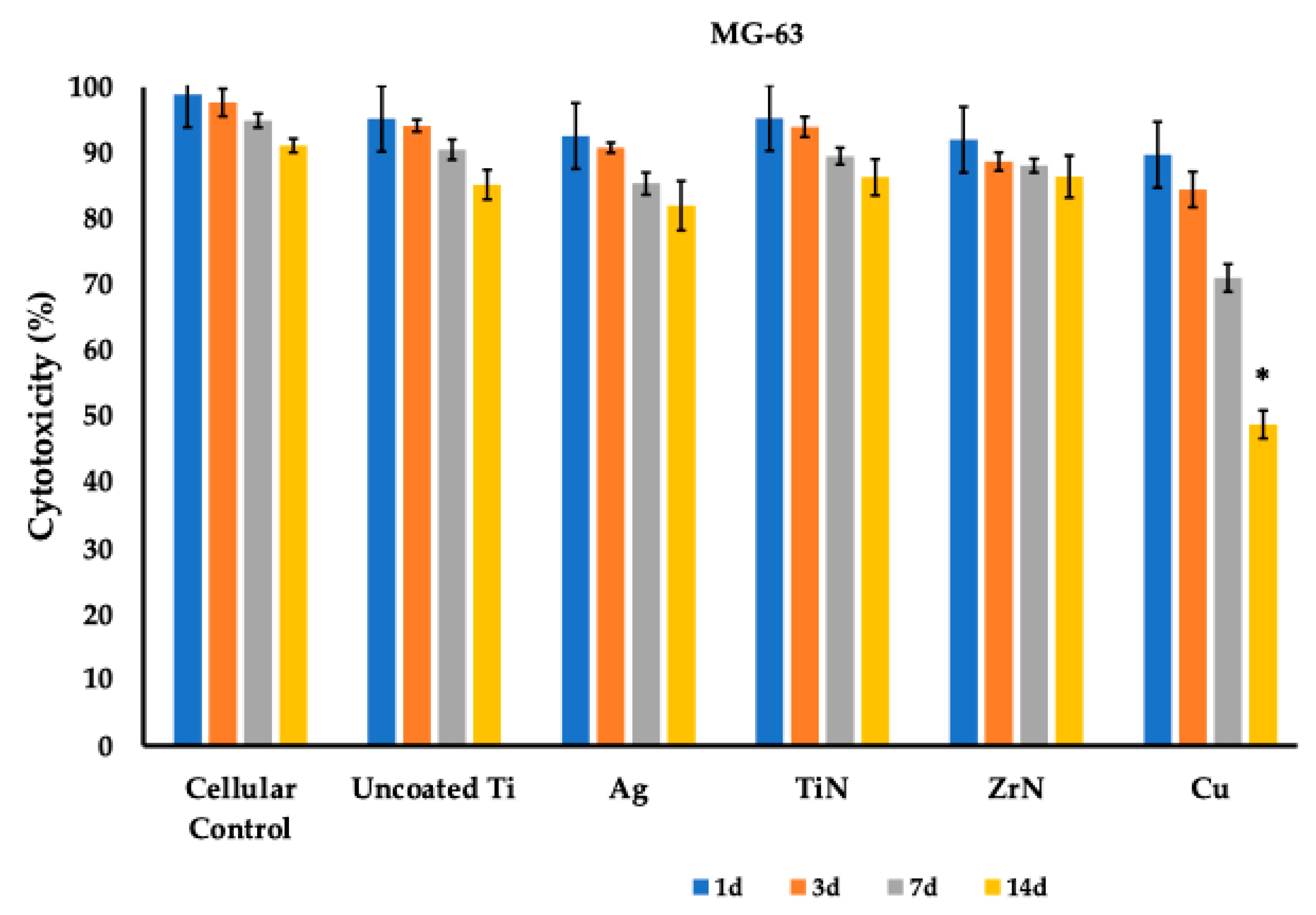

3.1. Cytotoxicity Profile of the Titanium Metal Coatings

3.2. Antibacterial Properties of the Microporous Titanium Metal Coatings

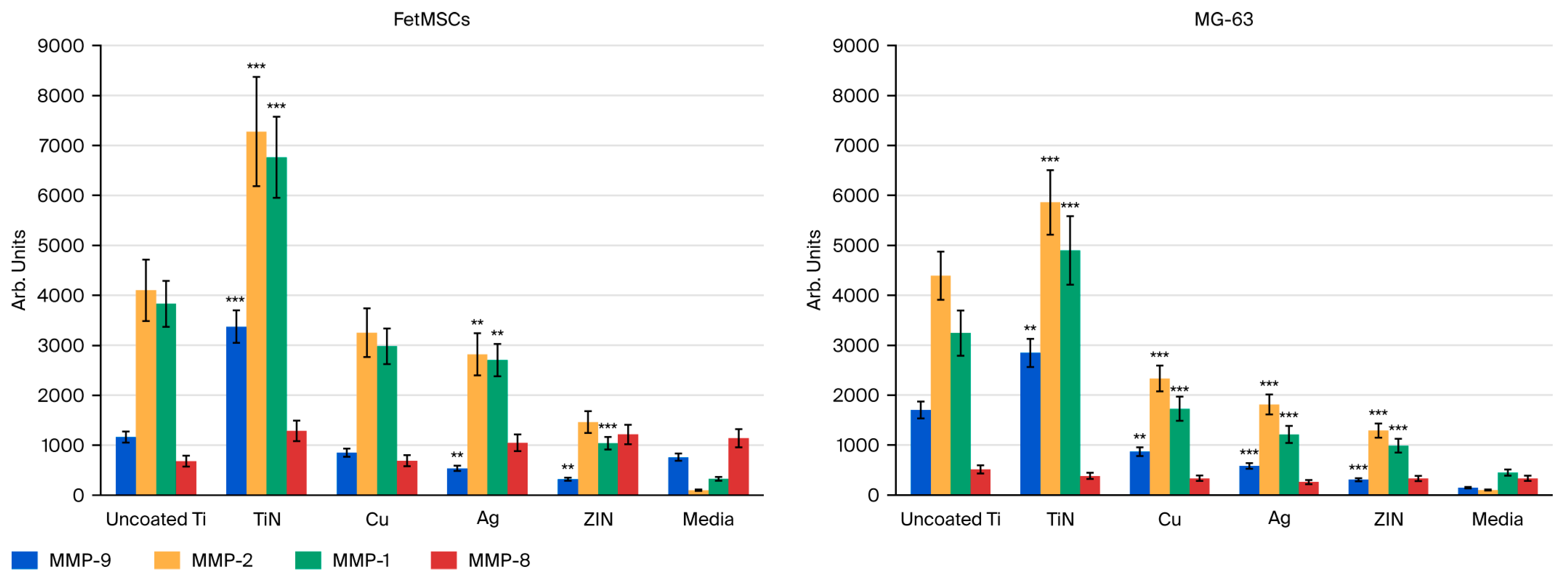

3.3. Induction of the Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity by Metal Coatings

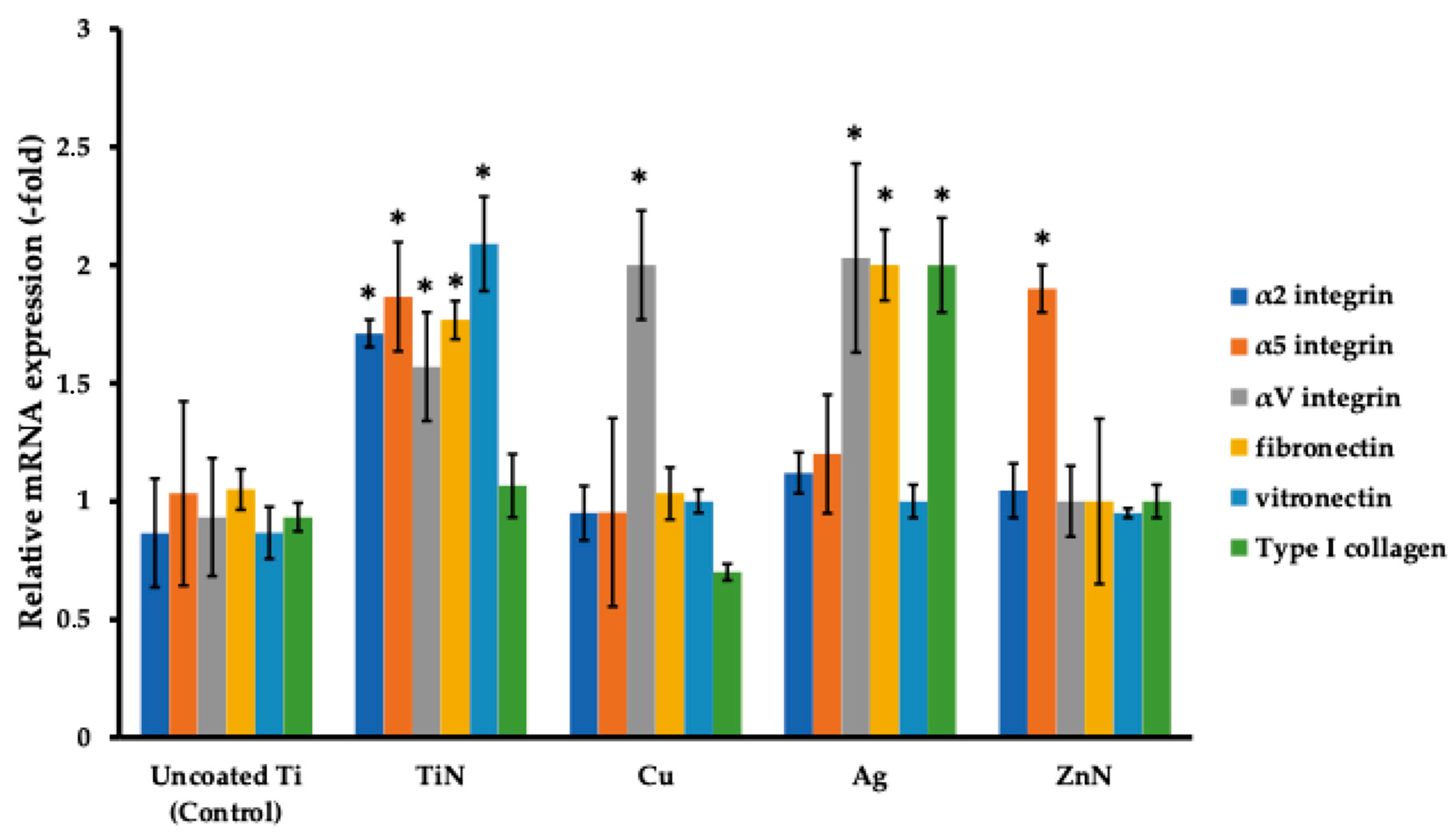

3.4. Analysis of Focal Adhesion Markers of FetMSCs Cultured on Ti Disks with Various Metal Coatings

3.5. Analysis of Osteogenic Markers of MG-63 Cells Cultured on Ti Disks with Various Metal Coatings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMP | bone mineral density |

| CaP | calcium phosphate |

| DSA | direct skeletal attachment |

| FAK | focal adhesion kinase |

| FetMSCs | fetal mesenchymal stem cells |

| HA | hydroxyapatite |

| ML-ALD | molecular layering of atomic layer deposition |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-di methyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB |

| RT-PCR | Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RTQ | removal torque tests |

| SBIP | skin- and bone-integrated pylon |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SLM | selective laser melting |

| SMAD4 | SMAD family member 4, Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TiN | Titanium Nitride |

| TMRM | Tetramethylrhodamine-methylester |

| ZrN | Zirconium Nitride |

References

- Farina, D.; Vujaklija, I.; Brånemark, R.; Bull, A.M.J.; Dietl, H.; Graimann, B.; Hargrove, L.J.; Hoffmann, K.P.; Huang, H.H.; Ingvarsson, T.; et al. Toward higher-performance bionic limbs for wider clinical use. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, Y.; Thompson, A.R.; Andaya, V.R.; Smith, K.; Doung, Y.C.; Gundle, K.R.; Hayden, J.B.; Tran, T.H.; Mohler, D.G.; Avedian, R.S.; et al. Survival of Proximal Tibial Endoprostheses Using Compressive Osseointegration: A Multi-Institution Retrospective Study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 132, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groundland, J.; Brown, J.M.; Monument, M.; Bernthal, N.; Jones, K.B.; Randall, R.L. What Are the Long-term Surgical Outcomes of Compressive Endoprosthetic Osseointegration of the Femur with a Minimum 10-year Follow-up Period? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2022, 480, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearing, B.V.; Gitajn, I.L.; Romereim, S.M.; Hoellwarth, J.S.; Wenke, J.C. Basic science review of transcutaneous osseointegration: Current status, research gaps and needs, and defining future directions. OTA Int. 2025, 8, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivas, S.; Samaur, H.; Yadav, V.; Boda, S.K. Soft and Hard Tissue Integration around Percutaneous Bone-Anchored Titanium Prostheses: Toward Achieving Holistic Biointegration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 1966–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevtsov, M.; Gavrilov, D.; Yudintceva, N.; Zemtsova, E.; Arbenin, A.; Smirnov, V.; Voronkina, I.; Adamova, P.; Blinova, M.; Mikhailova, N.; et al. Protecting the skin-implant interface with transcutaneous silver-coated skin-and-bone-intergrated-pylon (SBIP) in pig and rabbit dorsum models. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, M.; Pitkin, E.; Combs, S.E.; Meulen, G.V.; Preucil, C.; Pitkin, M. Comparison In Vitro Study on the Interface between Skin and Bone Cell Cultures and Microporous Titanium Samples Manufactured with 3D Printing Technology Versus Sintered Samples. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Borre, C.E.; Zigterman, B.G.R.; Mommaerts, M.Y.; Braem, A. How surface coatings on titanium implants affect keratinized tissue: A systematic review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braem, A.; Chaudhari, A.; Vivan Cardoso, M.; Schrooten, J.; Duyck, J.; Vleugels, J. Peri- and intra-implant bone response to microporous Ti coatings with surface modification. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Attarilar, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, B.; Tang, Y. Surface Modification Techniques of Titanium and its Alloys to Functionally Optimize Their Biomedical Properties: Thematic Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 603072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Ma, J.; Tian, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Tong, X.; Ma, X. Surface modification techniques of titanium and titanium alloys for biomedical orthopaedics applications: A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 227, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachar, P.; Bartakova, S.; Brezina, V.; Cvrcek, L.; Vanek, J. Cytocompatibility of implants coated with titanium nitride and zirconium nitride. Bratisl. Med. J. 2015, 116, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hove, R.P.; Sierevelt, I.N.; van Royen, B.J.; Nolte, P.A. Titanium-Nitride Coating of Orthopaedic Implants: A Review of the Literature. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 485975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Bhattacharya, K.; Dittrick, S.A.; Mandal, C.; Balla, V.K.; Sampath Kumar, T.S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Manna, I. In situ synthesized TiB-TiN reinforced Ti6Al4V alloy composite coatings: Microstructure, tribological and in-vitro biocompatibility. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, F.; Finke, B.; Zietz, C.; Bader, R.; Weltmann, K.D.; Polak, M. Antimicrobial surface modification of titanium substrates by means of plasma immersion ion implantation and deposition of copper. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 256, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkin, M.; Raykhtsaum, G. Skin Integrated Device. US Patent 8257435, 4 September 2012. Available online: http://www.google.com/patents/US8257435 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Ching, H.A.; Choudhury, D.; Nine, M.J.; Abu Osman, N.A. Effects of surface coating on reducing friction and wear of orthopaedic implants. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2014, 15, 014402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetz, M.C.; Fleischmann, E.W.; Konrad, C.H.; Schuetz, A.; Glatzel, U. Abrasion resistance of oxidized zirconium in comparison with CoCrMo and titanium nitride coatings for artificial knee joints. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 93, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galetz, M.C.; Seiferth, S.H.; Theile, B.; Glatzel, U. Potential for adhesive wear in friction couples of UHMWPE running against oxidized zirconium, titanium nitride coatings, and cobalt-chromium alloys. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 93, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-W.; Lee, H.-S.; Park, J.-H.; Shin, S.-M.; Wang, J.-P. Sintering of titanium hydride powder compaction. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 2, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrup, N.; Sharma, A.K.; Jacobsen, N.R.; Loeschner, K. Distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity of implanted silver: A review. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 2388–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SreeHarsha, K.S. Principles of Physical Vapor Deposition of Thin Films, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. xi, 1160p. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Chen, A.; Wu, M.; Tang, X.; Feng, H.; Liu, J.; Xie, G. A shellfish-inspired bionic microstructure design for biological implants: Enhancing protection of antibacterial silver-loaded coatings and promoting osseointegration. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 167, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G.W.; Stetler-Stevenson, W.G.; Kleiner, D.E. Zymography, Casein Zymography, and Reverse Zymography: Activity Assays for Proteases and their Inhibitors. In Proteolytic Enzymes: Tools and Targets; Sterchi, E.E., Stöcker, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, M.; Sohail, A.; Fridman, R. Assessment of gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) by gelatin zymography. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 878, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomi, M.W.; Kalinovsky, T.; Monterrey, J.; Rath, M.; Niedzwiecki, A. In vitro modulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in adult human sarcoma cell lines by cytokines, inducers and inhibitors. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Fischer, N.G.; Kong, X.; Sang, T.; Ye, Z. Hybrid coatings on dental and orthopedic titanium implants: Current advances and challenges. BMEMat 2024, 2, e12105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkioka, M.; Rausch-Fan, X. Antimicrobial Effects of Metal Coatings or Physical, Chemical Modifications of Titanium Dental Implant Surfaces for Prevention of Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Studies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirtharaj Mosas, K.K.; Chandrasekar, A.R.; Dasan, A.; Pakseresht, A.; Galusek, D. Recent Advancements in Materials and Coatings for Biomedical Implants. Gels 2022, 8, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jiang, B.; Yang, L.; Zhang, P.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Dual-functional titanium implants via polydopamine-mediated lithium and copper co-incorporation: Synergistic enhancement of osseointegration and antibacterial efficacy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1593545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, H.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Qin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Ren, L.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of osteogenesis and antibacterial activity of Cu-bearing Ti alloy in a bone defect model with infection in vivo. J. Orthop. Transl. 2021, 27, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, M.; Bakhshandeh, S.; van Hengel, I.A.J.; Lietaert, K.; van Kessel, K.P.M.; Pouran, B.; van der Wal, B.C.H.; Vogely, H.C.; Van Hecke, W.; Fluit, A.C.; et al. Antibacterial and immunogenic behavior of silver coatings on additively manufactured porous titanium. Acta Biomater. 2018, 81, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, M.; Pitkin, E.; Combs, S.E.; Yudintceva, N.; Nazarov, D.; Meulen, G.V.; Preucil, C.; Akkaoui, M.; Pitkin, M. Biocompatibility Analysis of the Silver-Coated Microporous Titanium Implants Manufactured with 3D-Printing Technology. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsymbal, S.; Li, G.; Agadzhanian, N.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dukhinova, M.; Fedorov, V.; Shevtsov, M. Recent Advances in Copper-Based Organic Complexes and Nanoparticles for Tumor Theranostics. Molecules 2022, 27, 7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.; Tang, X.; Wei, Q.; Liu, B.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y. In Situ Electrochemical Fabrication of Photoreactive Ag-Cu Bimetallic Nanocomposite Coating and Its Antibacterial-Osteogenic Synergy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 6326–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubayev, V.I.; Brånemark, R.; Steinauer, J.; Myers, R.R. Titanium implants induce expression of matrix metalloproteinases in bone during osseointegration. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2004, 41, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oum’hamed, Z.; Garnotel, R.; Josset, Y.; Trenteseaux, C.; Laurent-Maquin, D. Matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2, -9 and tissue inhibitors TIMP-1, -2 expression and secretion by primary human osteoblast cells in response to titanium, zirconia, and alumina ceramics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2004, 68, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Xie, J.; Hu, N.; Liang, X.; Chen, R.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Xu, C.; Huang, W.; Paul Sung, K.L. Titanium particles up-regulate the activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in human synovial cells. Int. Orthop. 2014, 38, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oliva, S.; Diomede, F.; Della Rocca, Y.; Mazzone, A.; Marconi, G.D.; Pizzicannella, J.; Trubiani, O.; Murmura, G. Anti-TLR4 biological response to titanium nitride-coated dental implants: Anti-inflammatory response and extracellular matrix synthesis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1266799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, U.; Nusselt, T.; Sewing, A.; Ziebart, T.; Kaufmann, K.; Baranowski, A.; Rommens, P.M.; Hofmann, A. The effect of different collagen modifications for titanium and titanium nitrite surfaces on functions of gingival fibroblasts. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, C.E.B.; Queiroz Neto, M.F.; Braz, J.; de Medeiros Aires, M.; Silva Farias, N.B.; Barboza, C.A.G.; Cavalcanti Júnior, G.B.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Alves Junior, C. Effect of plasma-nitrided titanium surfaces on the differentiation of pre-osteoblastic cells. Artif. Organs 2019, 43, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreiqat, H.; Valenzuela, S.M.; Nissan, B.B.; Roest, R.; Knabe, C.; Radlanski, R.J.; Renz, H.; Evans, P.J. The effect of surface chemistry modification of titanium alloy on signalling pathways in human osteoblasts. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7579–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaiya, B.B.; Kumar, S.; Pathan, M.S.H.; Patel, S.; Gupta, V.; Haque, M. The Impact of Implant Surface Modifications on the Osseointegration Process: An Overview. Cureus 2025, 17, e81576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, M.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Recent development and applications of electrodeposition biocoatings on medical titanium for bone repair. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 9863–9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshaya, S.; Rowlo, P.K.; Dukle, A.; Nathanael, A.J. Antibacterial Coatings for Titanium Implants: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonato, R.S.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Mello, A.; Rossi, A.M.; Carreira, A.C.O.; Sogayar, M.C.; Granjeiro, J.M. The Influence of rhBMP-7 Associated with Nanometric Hydroxyapatite Coatings Titanium Implant on the Osseointegration: A Pre-Clinical Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Ganguly, S.; Marvi, P.K.; Hassan, S.; Sherazee, M.; Mahana, M.; Shirley Tang, X.; Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R. Silicene-Based Quantum Dots Nanocomposite Coated Functional UV Protected Textiles with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties: A Versatile Solution for Healthcare and Everyday Protection. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2025, 14, e2404911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Feng, P.; Hao, M.; Tang, Y.; Wu, X.; Cui, W.; Ma, J.; Ke, C. Nanomaterials in Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy and Antibacterial Sonodynamic Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Gong, G.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Song, S.; Dai, H.; Wu, C.; Zou, Q.; Li, J.; et al. Mechanical and biological properties of 3D-printed porous titanium scaffolds coated with composite growth factors. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Fibronectin | F: CAGCCTCTGGTTCAGACTGC R: TCTTGTCCTACATTCGGCGG |

| Vitronectin | F: TACCCCAAGCTCATCCGAGA R: ACTGTAGCTATGGGCAGGGA |

| Type I collagen | F: GGTGTAAGCHCTGGTGGTTA R: CCAGTTCTTGGCTGGGATGT |

| α2 integrin | F: GGCTGGCCCAGAGTTTACAT R: ATCGAAAAATCTCCTAACTT |

| α5 integrin | F: TTCAACTTAGACGCGGAGGC R: ATCGCCCCCTCTCCTAACTT |

| αV integrin | F: CCTAGGCACCCTCCTTCTGA R: TCACATTTGAGGACCTGCCC |

| FAK | F: GTCGTCTGCCTTCGCTTCA R: AGCAGGCCACATGCTTTACT |

| Paxillin | F: AAAGTTGCGGGGCATAGACG R: CAAGAACACAGGCCGTTTGG |

| Vinculin | F: GAGCAAAACCATCTCCCCGA R: CTGCCTCAGCTACAACACCT |

| Osteopontin | F: CAGCAGCAGCAGGAGGAG R: ACGGCTGTCCCAATCAGAAG |

| Osteonectin | F: TCGGCATCAAGCAGAGGAAT R: GTCCCTAGAGCCCCTGAGAA |

| TGF-β1 | F: TGTCCAGGCAAGAAATGGCA R: AGGAACCGCAGCACTCATAC |

| SMAD4 | F: ATGCTCAGTGGCTTCTCGAC R: CCTAGGGGAGAGCAGGAAGG |

| Cellular Control | Uncoated Ti (Control) | Ag | TiN | ZrN | Cu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d | 98.93 (0.47) | 96.93 (1.27) | 94.87 (2.90) | 96.53 (1.42) | 95.67 (4.56) | 90.73 (1.43) |

| 3d | 97.83 (1.40) | 93.03 (1.46) | 92.20 (1.73) | 90.03 (0.81) | 95.20 (2.23) | 84.40 (4.63) |

| 7d | 95.17 (0.45) | 90.90 (2.02) | 87.50 (1.06) | 90.30 (0.90) | 91.40 (1.90) | 75.97 (4.94) |

| 14d | 91.20 (1.08) | 88.50 (0.72) | 82.30 (1.78) | 86.77 (1.96) | 90.93 (1.27) | 47.80 (2.50) |

| Cellular Control | Uncoated Ti (Control) | Ag | TiN | ZrN | Cu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d | 98.93 (0.55) | 95.20 (1.06) | 92.60 (2.17) | 95.33 (4.31) | 92.03 (2.92) | 89.73 (0.45) |

| 3d | 97.67 (2.10) | 94.17 (0.91) | 90.80 (0.78) | 93.97 (1.53) | 88.70 (1.37) | 84.47 (2.71) |

| 7d | 94.93 (1.05) | 90.53 (1.53) | 85.37 (1.68) | 89.53 (1.27) | 88.10 (1.06) | 71.03 (2.10) |

| 14d | 91.13 (1.06) | 85.20 (2.25) | 82.00 (3.75) | 86.33 (2.76) | 86.43 (3.19) | 48.77 (2.14) |

| Samples | MMP-9 | MMP-2 | MMP-1 | MMP-1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| Media | 762 | 73 | 100 | 15 | 328 | 39 | 1140 | 182 |

| Uncoated Ti (Control) | 1165 | 112 | 4103 | 615 | 3832 | 460 | 681 | 109 |

| TiN | 3376 | 324 | 7280 | 1092 | 6764 | 812 | 1287 | 206 |

| Cu | 852 | 82 | 3253 | 488 | 2981 | 358 | 693 | 111 |

| Ag | 539 | 52 | 2821 | 423 | 2704 | 325 | 1050 | 168 |

| ZrN | 321 | 31 | 1464 | 220 | 1040 | 125 | 1215 | 194 |

| Samples | MMP-9 | MMP-2 | MMP-1 | MMP-1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| Media | 150 | 15 | 100 | 11 | 451 | 63 | 336 | 54 |

| Uncoated Ti (Control) | 1705 | 169 | 4393 | 483 | 3244 | 454 | 513 | 82 |

| TiN | 2846 | 282 | 5860 | 645 | 4899 | 686 | 384 | 61 |

| Cu | 869 | 86 | 2335 | 257 | 1729 | 242 | 337 | 54 |

| Ag | 583 | 58 | 1815 | 200 | 1215 | 170 | 261 | 42 |

| ZrN | 307 | 30 | 1292 | 142 | 987 | 138 | 331 | 53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shevtsov, M.; Bozhokina, E.; Yudintceva, N.; Bobkov, D.; Lukacheva, A.; Nazarov, D.; Voronkina, I.; Smagina, L.; Pitkin, E.; Oganesyan, E.; et al. Enhancing the Antibacterial and Biointegrative Properties of Microporous Titanium Surfaces Using Various Metal Coatings: A Comparative Study. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060133

Shevtsov M, Bozhokina E, Yudintceva N, Bobkov D, Lukacheva A, Nazarov D, Voronkina I, Smagina L, Pitkin E, Oganesyan E, et al. Enhancing the Antibacterial and Biointegrative Properties of Microporous Titanium Surfaces Using Various Metal Coatings: A Comparative Study. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060133

Chicago/Turabian StyleShevtsov, Maxim, Ekaterina Bozhokina, Natalia Yudintceva, Danila Bobkov, Anastasiya Lukacheva, Denis Nazarov, Irina Voronkina, Larisa Smagina, Emil Pitkin, Elena Oganesyan, and et al. 2025. "Enhancing the Antibacterial and Biointegrative Properties of Microporous Titanium Surfaces Using Various Metal Coatings: A Comparative Study" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060133

APA StyleShevtsov, M., Bozhokina, E., Yudintceva, N., Bobkov, D., Lukacheva, A., Nazarov, D., Voronkina, I., Smagina, L., Pitkin, E., Oganesyan, E., Kayumov, A., Raykhtsaum, G., Matviychuk, M., Moxson, V., Akkaoui, M., Combs, S. E., & Pitkin, M. (2025). Enhancing the Antibacterial and Biointegrative Properties of Microporous Titanium Surfaces Using Various Metal Coatings: A Comparative Study. Prosthesis, 7(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060133