1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a well-established and cost-effective intervention for end-stage hip pathology, demonstrating high rates of implant survivorship and patient satisfaction [

1]. Nevertheless, the growing demand for THA—driven by an aging population and expanded surgical indications—poses increasing challenges for long-term implant durability. According to projections based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services dataset, the annual number of THA procedures in the United States is expected to rise by 176% by 2040 [

1]. Despite the overall success of THA, a subset of implants ultimately fail, requiring revision procedures that are associated with increased surgical complexity, prolonged recovery, and higher complication rates [

2,

3,

4]. Failure mechanisms are diverse, encompassing mechanical and biological etiologies [

2,

3,

4]. While aseptic loosening and wear-induced osteolysis remain the leading causes of late revision [

5], early failures are commonly linked to instability, periprosthetic joint infection, and femoral stem subsidence [

5,

6].

In the context of revision THA, particularly in cases involving severe proximal bone loss, the use of tapered, fluted titanium stems (TFTSs) has become increasingly common in complex femoral reconstruction during revision THA [

7,

8]. The introduction of monoblock designs, such as the Wagner stem in the late 1980s, represented a significant advancement in managing complex femoral deficiencies [

9]. However, monoblock stems are limited by a lack of intraoperative adjustability, contributing to high subsidence rates (greater than 5 mm in 21–34% of cases) and dislocation [

9,

10].

Modular TFTSs were developed to overcome the limitations of monoblock stems by enabling independent control over proximal and distal fixation, thus allowing for enhanced intraoperative flexibility and improved restoration of hip biomechanics [

11]. These designs provide stable distal fixation through a fluted, tapered geometry. At the same time, modularity in the proximal body enables accurate restoration of hip biomechanics via intraoperative customization of offset, anteversion, and length [

11]. Although concerns remain regarding mechanical failure at the modular junction—particularly in patients with compromised bone stock or elevated body mass index (BMI)—recent studies have reported improved mechanical reliability and favorable clinical outcomes with the latest generation of modular tapered stems [

12,

13].

The M-Vizion

® Femoral Revision System is a cementless, modular, tapered, and fluted titanium stem specifically engineered for use in both complex primary and revision THA procedures. Its design enables enhanced intraoperative flexibility through the independent adjustment of length, diameter, version, and offset, accommodating varied femoral anatomies and bone loss patterns [

11,

12,

13]. Given the technical demands of femoral reconstruction in complex primary and revision settings, modular tapered stems are increasingly utilized to optimize implant stability and restore patient-specific anatomy [

11,

12,

13]. However, clinical evidence supporting the performance of specific modular designs, particularly in the context of acute femoral fractures or stem revisions, remains limited [

7,

12,

13]. In this context, we hypothesized that the M-Vizion

® modular stem would yield favorable short-term clinical and radiographic outcomes, with a low incidence of complications and reliable osseointegration. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated patients undergoing THA for unstable lateral femoral fractures or femoral stem revision.

This study aimed to evaluate the two-year clinical and radiographic outcomes of the M-Vizion modular stem (Medacta International, Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) in patients undergoing THA for unstable lateral femoral fractures or femoral stem revision.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective observational study was approved by the Territorial Ethics Committee of Regione Calabria (Protocol No. 96/2025, 30 June 2020) and conducted at the “Franco Faggiana” Orthopaedic Institute (Reggio Calabria, Italy). Due to the study’s retrospective nature, written informed consent was obtained from all participants during their first postoperative follow-up.

The institutional arthroplasty registry was queried to identify patients who underwent complex primary or revision total hip arthroplasty using a cementless tapered, fluted, modular titanium stem system (M-Vizion®; Medacta International, Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) between September 2020 and March 2023.

2.2. Patient Eligibility and Selection Criteria

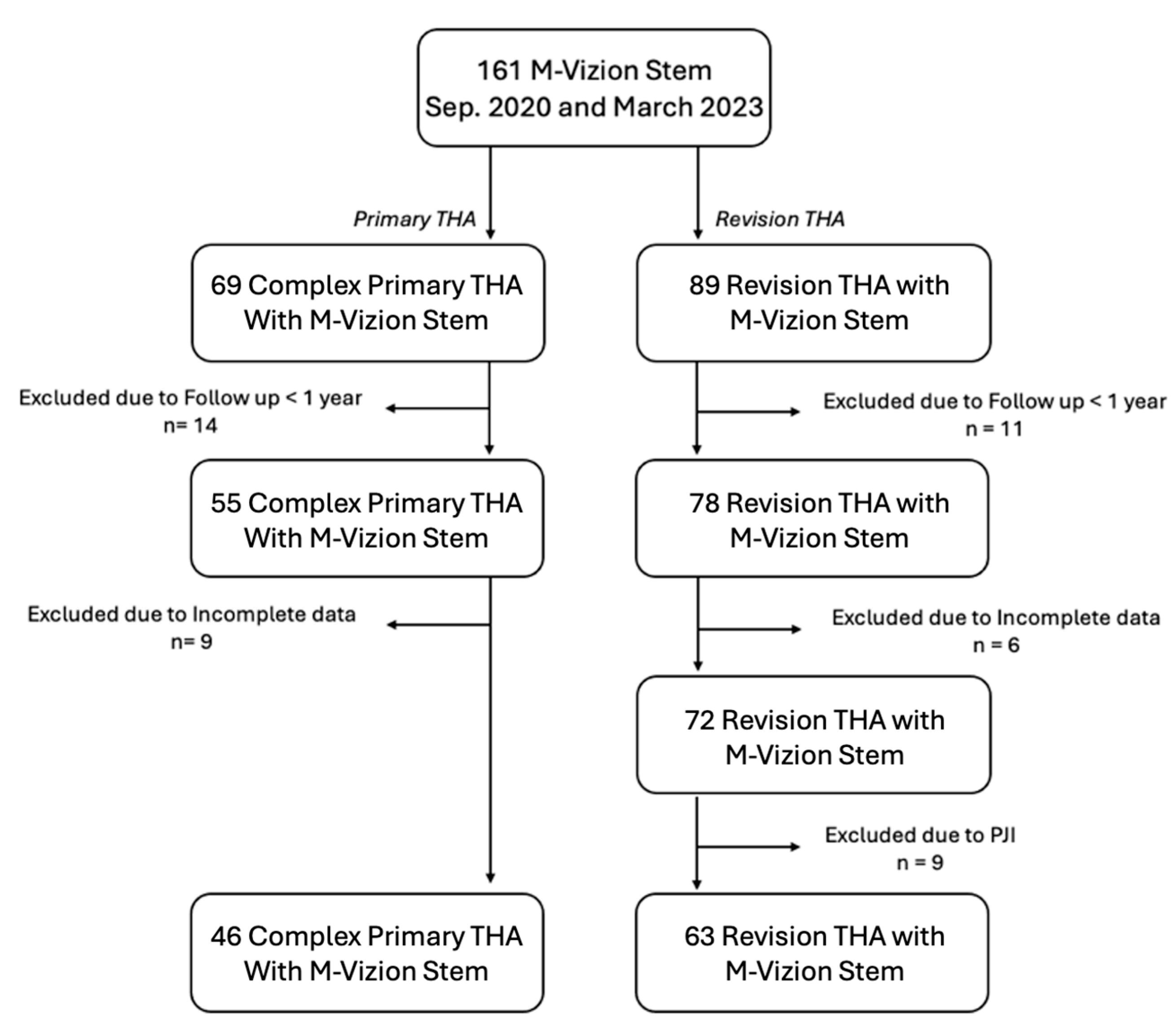

During the study period, a total of 161 patients underwent THA procedures utilizing the M-Vizion

® cementless modular tapered fluted titanium stem system. Patients were included in the analysis if they had complete clinical and radiographic data with a minimum follow-up of 12 months. Exclusion criteria were shorter follow-up, incomplete datasets, or a diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI). After applying these criteria, 109 patients were included in the final analysis: 46 underwent complex primary THA and 63 underwent revision THA (

Figure 1).

Data were extracted from the institutional arthroplasty registry and cross-verified with electronic medical records. Extracted variables included patient demographics (age, sex, BMI), surgical indication, type of procedure (complex primary vs. revision), operative details (components used, surgical approach), and follow-up data. Radiographic measurements and clinical scores were retrieved from standardized follow-up documentation completed at defined intervals. Any missing or inconsistent data were resolved through direct review of imaging archives and patient records.

For each patient included in the analysis, the following variables were collected: age at the time of surgery, sex, body mass index (BMI), surgical indication, and whether the procedure involved complex primary or revision THA. In the revision group, additional data were collected regarding the specific indication for revision (e.g., periprosthetic fracture, aseptic loosening, adverse reaction to metal debris, recurrent dislocation, or component failure), as well as whether the revision involved only the femoral component or both the femoral and acetabular components. For comparative purposes, all variables were organized and summarized separately for the complex primary and revision THA groups.

2.3. Implant Characteristics

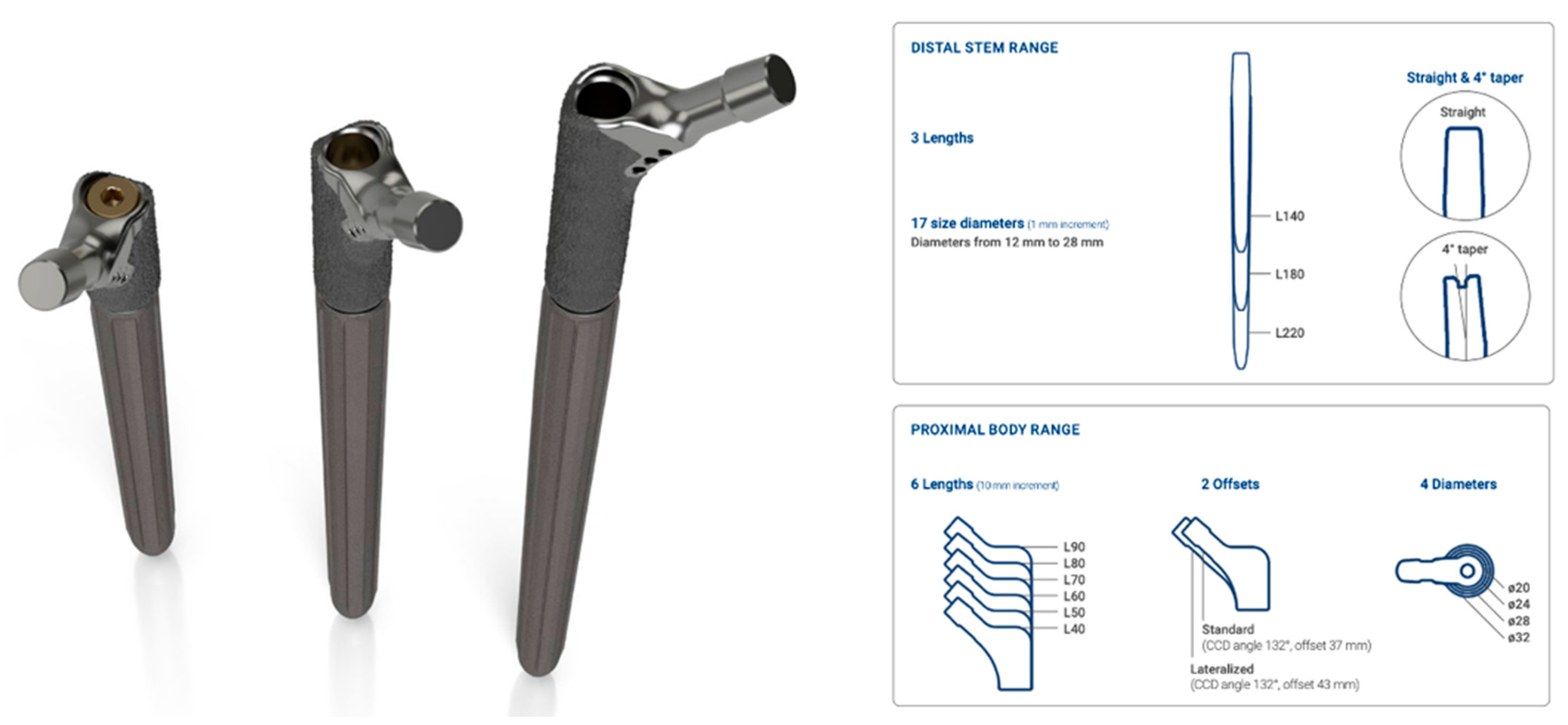

All procedures were performed by the senior author (P.C.). The M-Vizion

® Modular Femoral Revision System (Medacta International, Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) was used for femoral reconstruction in both complex primary and revision THA cases (

Figure 2).

The M-Vizion® system features a two-part modular design consisting of independently selectable proximal and distal components, allowing for adaptability to a wide range of femoral anatomies and bone defects. The proximal body is available in multiple sizes and with two offset options: standard (0 mm) and lateralized (+10 mm). It is coated with Mectagrip®, a titanium plasma spray designed to enhance proximal fixation and promote osseointegration.

The distal stem is manufactured from forged Ti-6Al-7Nb alloy, with available lengths ranging from 140 mm to 220 mm and diameters between 14 mm and 26 mm. It has a tapered, fluted design that provides axial and rotational stability by engaging the diaphyseal cortex.

This modular architecture enables independent intraoperative adjustment of length, offset, and version, offering a tailored approach to complex reconstructions [

11,

12,

13]. The proximal and distal components can be assembled either in vivo or on the back table. Proper junctional stability is ensured using a calibrated torque-limiting screwdriver. Furthermore, the metaphyseal component includes three dedicated holes designed to accommodate ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) cerclage cables for supplemental fixation when necessary.

2.4. Assessment of Clinical, Radiographic, and Functional Outcomes

Standardized anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were independently evaluated by two observers (G.C. and F.D.M.) at the 6-month postoperative follow-up. The 6-month interval was selected based on evidence indicating that most femoral stem subsidence typically occurs within the first 6 to 8 weeks following implantation [

14].

Stem subsidence was quantified by measuring the vertical distance between the apex of the greater trochanter and the most proximal visible point on the shoulder of the femoral stem on both immediate postoperative and 6-month radiographs [

14]. In cases where notable discrepancies in radiographic projection between time points were identified, additional imaging was obtained to ensure measurement reliability. Patients with persistent inconsistencies in radiographic quality, despite repeated imaging, were excluded from the subsidence analysis.

Radiographic assessment also included evaluation of radiolucent lines, defined as radiolucent zones exceeding 2 mm in width between the implant and the surrounding bone, not previously visible on earlier radiographs. These were further categorized as progressive or non-progressive and classified according to their location using the Gruen zone system [

15]. Additionally, the presence and severity of heterotopic ossifications were assessed using the Brooker classification system [

16].

Functional and patient-reported outcomes were assessed by the same two observers who conducted the radiographic evaluations (G.C. and F.D.M.) during each follow-up visit. During each follow-up visit, patients completed the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) and the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS) questionnaires to evaluate functional performance and joint awareness.

The FJS questionnaire was administered postoperatively to all patients in both the complex primary and revision THA groups. In contrast, the HOOS questionnaire was administered preoperatively only in the revision THA group. This was because all patients in the complex primary group underwent arthroplasty following acute femoral fractures and thus did not present with chronic degenerative pathology warranting preoperative functional assessment. Both outcome measures were collected again at the 1- and 2-year postoperative time points for longitudinal comparison.

All intraoperative and postoperative complications were systematically recorded throughout the study period to provide a comprehensive overview of the safety profile associated with the use of the M-Vizion® modular stem. Recorded complications included surgical site infections, intraoperative fractures, dislocations, mechanical failures, and any adverse events requiring reoperation or revision.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Given the study’s retrospective nature and the use of pre-existing clinical data, no formal sample size calculation was performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as counts and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons between the complex primary THA group and the revision THA group were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. The Kruskal–Wallis test was chosen instead of ANOVA because it does not require the assumption of normality of data distribution, which may not be met in clinical datasets. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Complex Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty

In the complex primary THA group (

Table 1), the mean age at surgery was 81 ± 11.8 years (range, 49–97), with 34 women (73.9%) and 12 men (26.1%). The mean BMI was 26 ± 3.6 kg/m

2 (range, 18–36).

As reported in

Table 2, the most common surgical indication was unstable lateral femoral fracture (33 cases, 71.7%), followed by failed osteosynthesis (13 cases, 28.3%).

The mean follow-up duration was 33.3 ± 7.2 months (range, 12–47 months). Surgical time was less than 60 min in 14 cases (30.4%), between 60 and 80 min in 28 cases (60.9%), and greater than 80 min in 4 cases (8.7%). Estimated blood loss was less than 500 mL in 11 patients (23.9%), between 500 and 1000 mL in 24 patients (52.2%), and more than 1000 mL in 10 patients (21.7%).

Three patients (6.5%) died due to causes unrelated to surgery at a mean of 18.6 ± 5.4 months postoperatively. Importantly, none of these patients required femoral component revision during the follow-up period.

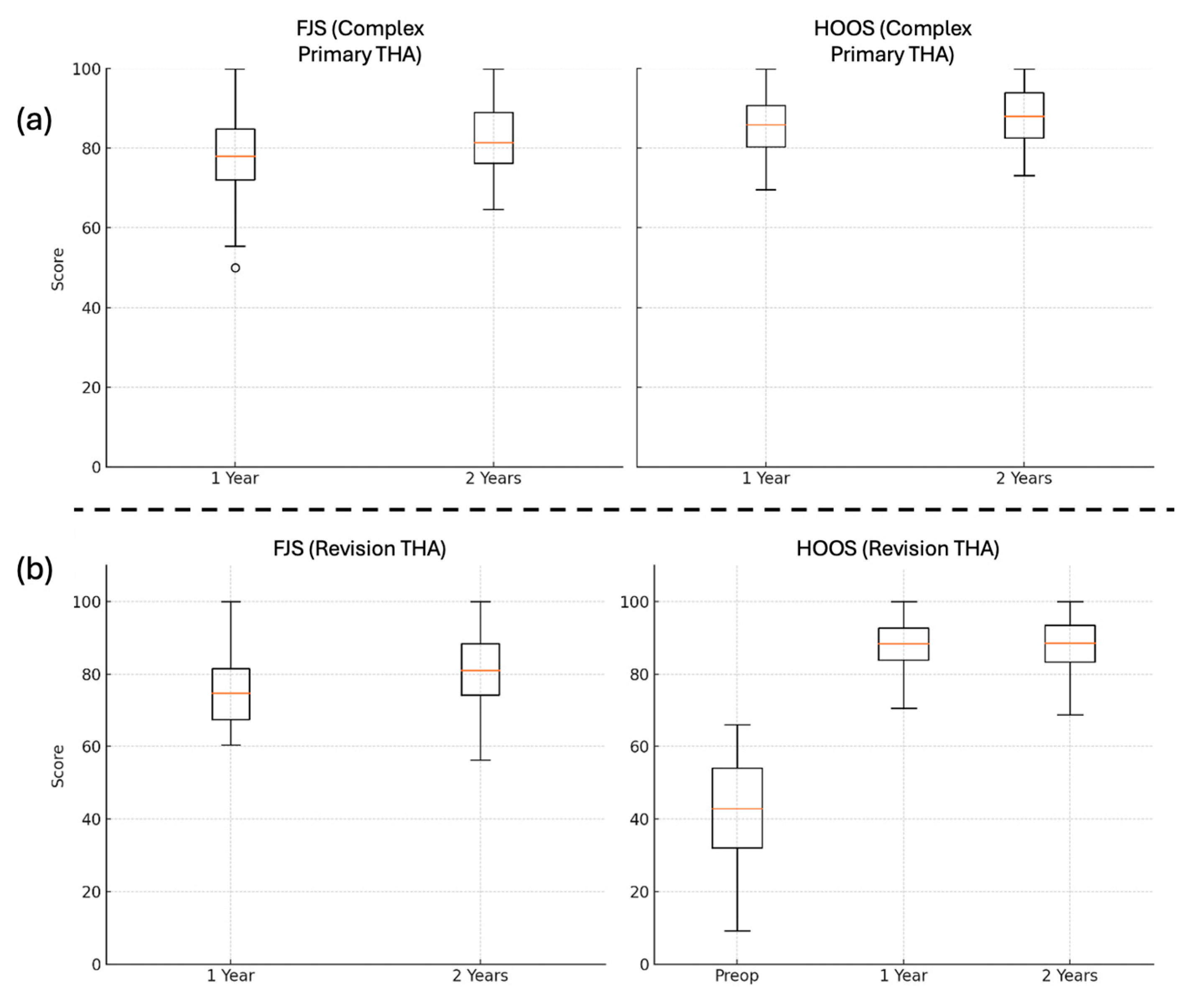

At the 1-year follow-up, the mean FJS was 74.8 ± 11.3 (range, 50–100), increasing to 81.2 ± 10.0 (range, 64.6–100) at 2 years (

Figure 3a).

The mean HOOS at 1 year was 79.4 ± 7.6 (range, 69.6–100) and improved to 84.9 ± 7.1 (range, 73.1–100) at 2 years (

Figure 3a). FJS showed a statistically significant improvement between 1 and 2 years (

p = 0.028), while the increase in HOOS was not statistically significant (

p = 0.087).

Mean stem subsidence was 2.1 ± 3.9 mm. Subsidence greater than 5 mm was observed in four patients (8.7%). No cases of aseptic loosening were reported. Non-progressive radiolucent lines were detected in five cases (10.8%). According to the Brooker classification [

16], grade 1 heterotopic ossification was present in six patients (13%).

Intraoperative complications occurred in three patients (6.5%). These included two greater trochanter fractures (4.3%) managed with wires/cerclage and one posterior acetabular wall fracture (2.2%) treated using a multihole acetabular component.

Postoperatively, two patients (4.3%) experienced a single hip dislocation managed with closed reduction. One patient (2.2%) sustained a Vancouver C periprosthetic fracture following a low-energy fall and was managed with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), without requiring femoral component revision. One patient (2.2%) developed a PJI, treated with a two-stage revision.

3.2. Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty

In the revision THA group, the mean age at the time of surgery was 74.0 ± 9.9 years (range, 52–88), with 37 women (58.7%) and 26 men (41.3%), and a mean BMI of 27.5 ± 3.2 kg/m

2 (range, 20–35), as shown in

Table 1.

The most common surgical indications were aseptic loosening (24 cases, 38.1%) and adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD) (12 cases, 19.0%), followed by periprosthetic joint infection (9 cases, 14.3%), as detailed in

Table 2.

An isolated femoral component revision was performed in 38 patients (60.3%), while both femoral and acetabular components were revised in 25 patients (39.7%).

The mean follow-up was 31.8 ± 6.9 (range, 12–44) months. Surgical time was <60 min in 3 cases (4.8%), 60–80 min in 15 cases (23.8%), and >80 min in 45 cases (71.4%). Blood loss was <500 mL in 10 cases (15.9%), 500–1000 mL in 35 cases (55.6%), and >1000 mL in 18 cases (28.6%). Three patients (9.1%) died from unrelated causes at a mean follow-up of 14.3 months; none required femoral revision.

At the 1-year follow-up, the mean FJS was 74.7 ± 9.9 (range, 60–100), increasing to 78.4 ± 11.6 (range, 61.3–100) at 2 years. The mean preoperative HOOS was 71.0 ± 9.8 (range, 51.6–88.3) and improved to 88.3 ± 6.6 (range, 66.1–100) at 2 years (

Figure 3b).

Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in HOOS between the 1-year and 2-year follow-up (p = 0.91), whereas FJS demonstrated a statistically significant improvement over the same period (p < 0.001).

Stem subsidence was 1.8 ± 4.0 mm, with subsidence >5 mm observed in five cases. One patient presented with 10 mm of subsidence at 6 months but remained asymptomatic and was considered clinically and radiographically stable. Non-progressive radiolucent lines were observed in six patients (9.5%).

Heterotopic ossifications developed in eight patients (12.7%), with six cases classified as Brooker grade I (9.5%) and two cases as grade II (3.2%) [

16] (

Table 2).

One patient (1.6%) experienced an intraoperative greater trochanter fracture, managed with a trochanteric plate and screws. Two patients (3.2%) experienced postoperative dislocation: one case was managed with closed reduction, while the other, characterized by recurrent instability, required femoral component revision. Two patients (3.2%) developed PJI, both managed with two-stage revision.

A summary of the main clinical, radiographic, and functional outcomes for both the complex primary THA and revision THA groups is provided in

Table 3. This table highlights the low complication rates, minimal stem subsidence, and the improvements observed in both FJS and HOOS between the 1-year and 2-year follow-up evaluations.

4. Discussion

The use of TFTSs has been extensively documented in the context of revision THA, where their mechanical stability, modularity, and ability to achieve secure diaphyseal fixation make them a preferred option in the presence of deficient proximal femoral bone stock. Conversely, evidence supporting their application in complex primary THA—procedures often characterized by severe deformity, previous fracture fixation, or bone loss requiring reconstructive strategies comparable to revision settings—remains relatively scarce. Only a limited number of studies have specifically investigated outcomes of complex primary THA performed with TFTSs [

4,

9,

14,

16], and these typically involve heterogeneous patient populations, small sample sizes, and varied follow-up protocols. In contrast, most of the available literature focuses on the use of TFTSs in revision THA [

12,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], where their role is well established. Importantly, several frequently cited studies are not directly comparable to the present investigation: one exclusively addresses re-revision THA [

18], while others evaluate femoral stems that do not conform to the established definition of a TFTS system [

19,

20]. Consequently, there remains a paucity of high-quality comparative evidence assessing the same TFTS design—specifically, the M-Vizion

® stem—across both complex primary and revision THA. The present study was conceived to address this gap by systematically evaluating intraoperative and postoperative complication rates, stem subsidence, and patient-reported functional outcomes in these two challenging but distinct clinical scenarios.

In the complex primary THA group, the intraoperative complication rate was 6.5%, postoperative complications occurred in 8.7% of cases, mean stem subsidence was 2.1 ± 3.9 mm, and clinically significant subsidence (>5 mm) was recorded in 8.7% of patients. Between the first and second postoperative year, the FJS increased by 10%, while the HOOS improved by 8.5%. These findings are positioned toward the lower end of the ranges reported in the literature for complex primary THA using TFTSs, where intraoperative complication rates range from 6% to 15% and postoperative complication rates from 8% to 18% [

4,

9,

14]. Mean subsidence values in the present series were comparable to those observed in previous reports [

9,

16], with similar frequencies of clinically relevant subsidence. Improvements in PROMs (FJS, HOOS) were consistent with, or slightly superior to, those documented in smaller cohorts [

14,

16], suggesting that the M-Vizion

® stem may provide favorable functional recovery even in demanding primary reconstructions. Nonetheless, these results should be interpreted considering inter-study variability in baseline demographic and clinical characteristics—such as patient age, sex distribution, bone quality, body mass index (BMI), and follow-up duration—that may influence complication rates and functional outcomes.

In the revision THA group, intraoperative and postoperative complication rates were 1.6% and 6.3%, respectively. Mean stem subsidence was 1.8 ± 4.0 mm, with subsidence greater than 5 mm occurring in 7.9% of cases. Between the first and second postoperative year, the FJS increased by 12% and the HOOS by 9.2%. These values are in line with previously reported outcomes for TFTSs in revision THA [

12,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], where mean subsidence typically ranges from 1.5 to 3.0 mm and complication rates generally remain in the single-digit range. It is important to note that in some comparative studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], implant survivorship was a primary endpoint, whereas survivorship was not assessed in the present analysis. Additionally, the revision cohort in our study exhibited a higher comorbidity burden, more variable bone stock, and a greater prevalence of multiple prior hip surgeries compared with the complex primary group—factors likely to influence both complication profiles and functional recovery trajectories [

24,

25].

The present study has several limitations. First, patients were not randomly assigned to the study groups, reflecting the retrospective nature of the investigation and potentially introducing selection bias. Second, although relevant preoperative data were collected prospectively, the exclusion of patients with incomplete or missing follow-up data may have led to attrition bias. Third, for 11 patients in the complex primary THA group, outcome measures were available only postoperatively, as these procedures were performed in an emergency setting; consequently, changes in PROMs from preoperative baseline to first follow-up could not be determined in these cases. Fourth, the latest follow-up (33.0 months for complex primary THA and 31.8 months for revision THA) was relatively short, and longer follow-up is required to confirm the durability of the observed clinical and radiographic outcomes.