Lessons Learnt from Götz of the Iron Hand

1. Introduction

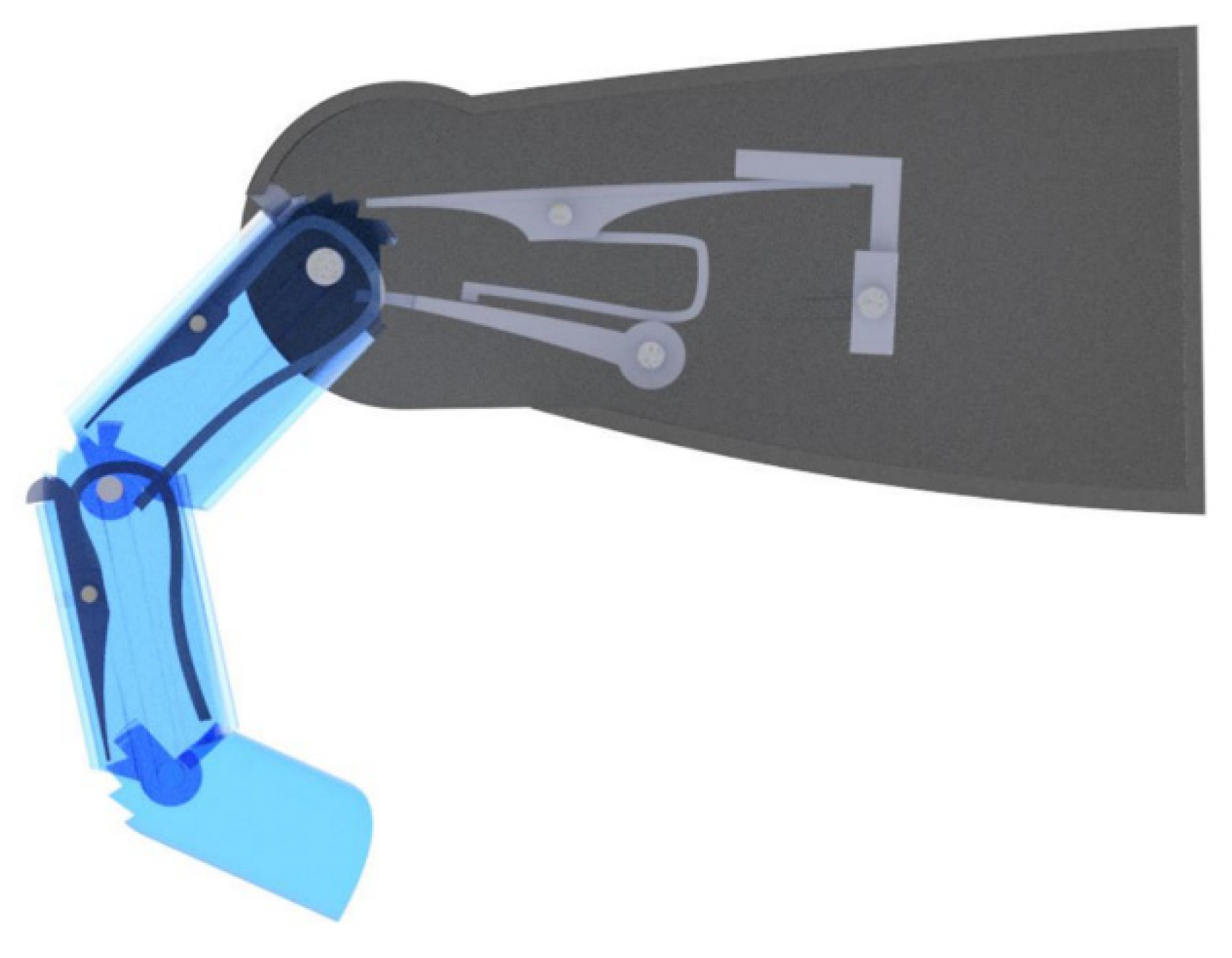

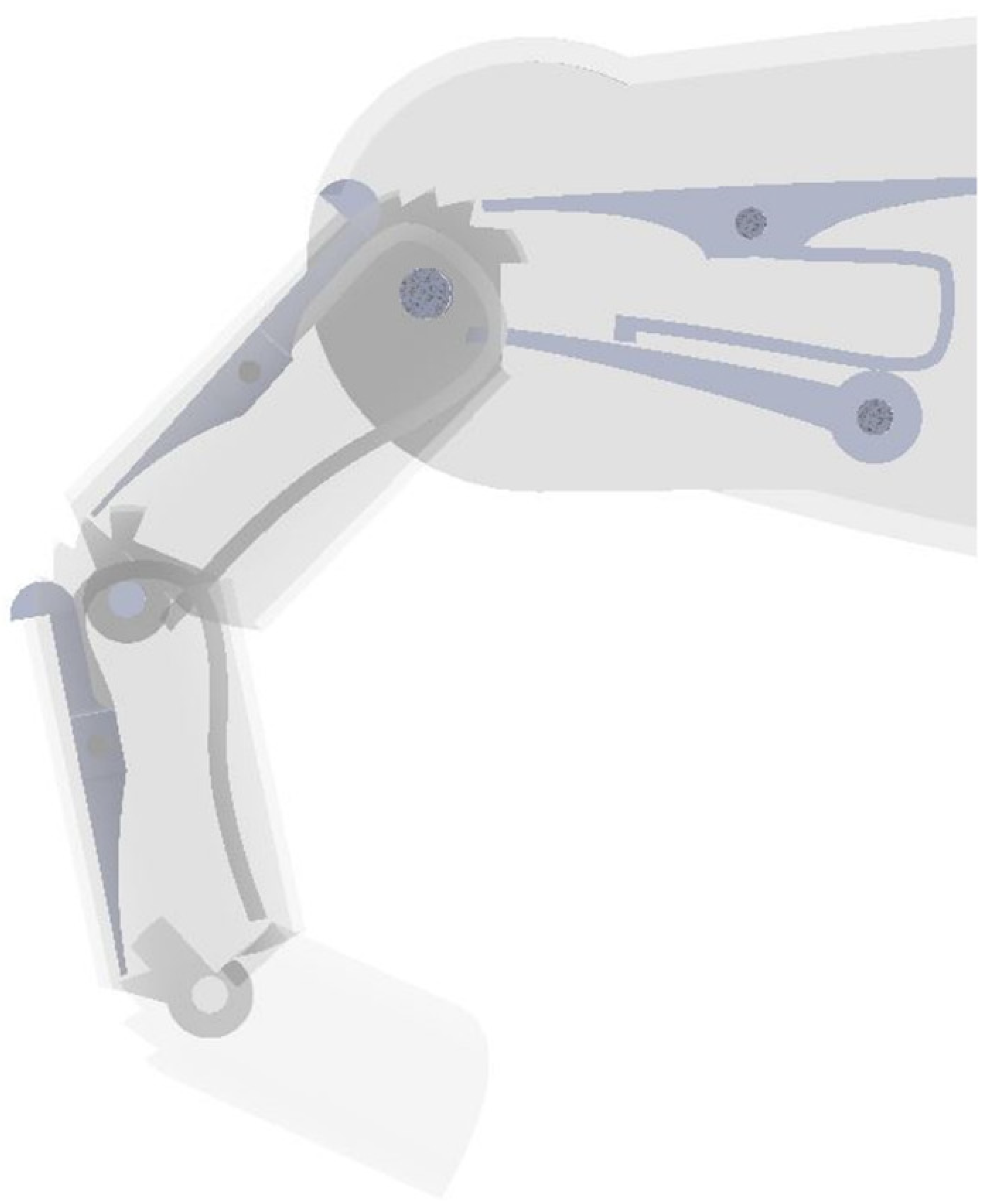

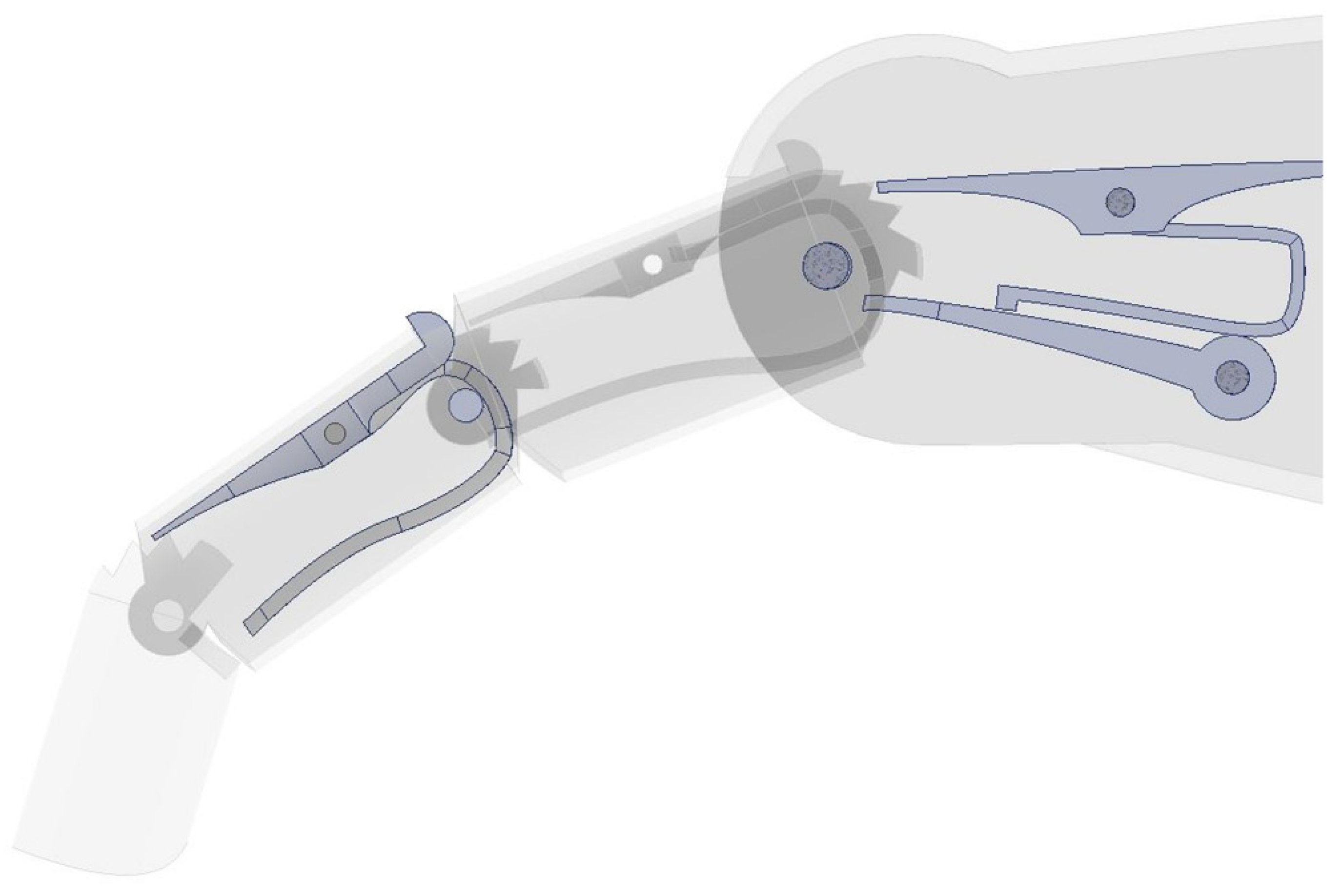

2. 3D-CAD Reconstruction of the Second “Iron Hand”

3. Lessons Learnt

- This ancient hand prosthesis has very complicated mechanics;

- The very detailed Mechel publication does not explain every detail of the hand and is not quite 1:1 in scale.

- When printing the parts with a multi-material polymer printer, the levers and springs of the finger mechanism broke after only a few seconds, while the polymer replica of the first hand still functions perfectly after years of constant use. This indicates that not all prosthetic hand designs are suitable for 3D polymer printing: Especially for such fragile parts, such as those inside the second prosthetic hand, a CAD-based computerized numerical control (CNC) fabrication from metal should be considered. In fact, the original hand in the museum of Jagsthausen, Germany, is also made of sheet alloy. Information on the stability, and thus the choice for the appropriate material, can be simulated in advance, e.g., with a dynamic finite element method (FEM) analysis.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinert, O.; Otte, A. 3-D CAD-Rekonstruktion der ersten “Eisernen Hand” des Reichsritters Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562) [3D CAD reconstruction of the first “Iron Hand” of German knight Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562)]. Arch. Kriminol. 2017, 240, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A.; Weinert, O.; Junk, S. 3D-Multimaterial Printing—Knight Götz von Berlichingen’s Trendsetting “Iron Hand”. Science. Eletter from 2 December 2017. Available online: https://www.science.org/do/10.1126/comment.702964/full/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Otte, A.; Weinert, O.; Junk, S. 3-D CAD-Rekonstruktion der erstens “Eisernen Hand” des Reichsritters Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562): 1. Fortsetzung: Funktionsprüfung mittels 3-D Druck. [3D CAD reconstruction of the first “Iron Hand” of German knight Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562)—First continuation: Function test by means of 3D print]. Arch. Kriminol. 2017, 240, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. Invasive versus non-invasive neuroprosthetics of the upper limb: Which way to go? Prosthesis 2020, 2, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, O.; Otte, A. 3-D CAD-Rekonstruktion der ersten “Eisernen Hand” des Reichsritters Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562)—2. Fortsetzung: Funktionsprüfung eines Umbaus zu einem sensomotorischen, controllergesteuerten intelligenten Fingersystem. [3D CAD reconstruction of the first “Iron Hand” of German knight Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562)—Second continuation: Functional test of a conversion to a sensorimotor, controller-controlled intelligent finger system]. Arch. Kriminol. 2019, 243, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. Smart neuroprosthetics becoming smarter, but not for everyone? eClinicalMedicine 2018, 2–3, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte, A.; Hazubski, S. Die erste “Eiserne Hand” des Reichsritters Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562): Weitere 3-D CAD-Rekonstruktionen. [The first “Iron Hand” of German knight Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562): Further 3D CAD reconstructions]. Arch. Kriminol. 2020, 246, 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. 3D Computer-Aided Design Reconstructions and 3D Multi-Material Polymer Replica Printings of the First “Iron Hand” of Franconian Knight Gottfried (Götz) von Berlichingen (1480–1562): An Overview. Prosthesis 2020, 2, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, A. Christian von Mechel’s Reconstructive Drawings of the Second “Iron Hand” of Franconian Knight Gottfried (Götz) von Berlichingen (1480–1562). Prosthesis 2021, 3, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otte, A. Lessons Learnt from Götz of the Iron Hand. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 444-446. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis4030035

Otte A. Lessons Learnt from Götz of the Iron Hand. Prosthesis. 2022; 4(3):444-446. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis4030035

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtte, Andreas. 2022. "Lessons Learnt from Götz of the Iron Hand" Prosthesis 4, no. 3: 444-446. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis4030035

APA StyleOtte, A. (2022). Lessons Learnt from Götz of the Iron Hand. Prosthesis, 4(3), 444-446. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis4030035