1. Introduction

The search for analytical solutions of wave equations for charged particles in intense electromagnetic fields remains an active research area. Such solutions are essential for understanding laser-induced phenomena in the high-intensity regime [

1,

2]. In particular, the well-known Volkov states, i.e., the exact solutions of the Dirac equation (electrons) [

3], Klein–Gordon equation (scalar charged particles) [

4], or Schrödinger equation [

5] in a classical plane-wave field, provides the basis for analyzing processes such as nonlinear Compton scattering, multiphoton ionization, and electron–positron pair production without restoring to perturbative expansions (see, for instance, [

6]). This non-perturbative framework is crucial when considering strong fields, where conventional perturbation theory often breaks down [

7].

Also, exact analytical solutions of the Dirac and Klein–Gordon equations, which underpin relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics (QED), have been derived for various classes of external field configurations, including crossed and longitudinal fields and beam guides [

8], monochromatic plane waves in media [

9,

10], and rotating electric fields [

11] (see the review by Bagrov and Gitman [

12] for earlier works). Another particular line of work concerns solutions of the Dirac equation in quantized electromagnetic fields, which capture quantum fluctuations of light. These solutions enable comparison between semiclassical and fully quantized approaches and are especially relevant for time-dependent fields, where conservation laws break down and semiclassical methods fail to determine photon absorption or emission [

13]. They also provide a foundation for studying electron–photon entanglement, decoherence, and quantum correlations in strong-field regimes [

14]. Notable examples include the cases of an electron in a quantized electromagnetic plane wave [

15,

16,

17], in a combined quantized wave and homogeneous magnetic field [

13,

18,

19], in a single-mode field with arbitrary polarization [

20,

21], and in a multimode quantized field [

22] (see [

12] for earlier works).

Recently, considerable interest has focused on the intrinsic entanglement of Dirac wave functions. Entanglement, a hallmark of nonclassicality, describes correlations so strong that subsystems cannot be described independently. With the advent of quantum information science, it has become a key resource for superdense coding, teleportation, cryptography, and precision measurements beyond classical limits [

23,

24,

25]. Unlike entanglement between distinct particles (e.g., polarization entanglement of photon pairs), intrinsic (intraparticle) entanglement refers to correlations among internal degrees of freedom of a single particle. A well-known example is the parity–spin entanglement in Dirac equation solutions, extensively studied in [

26,

27,

28], including the role of arbitrary Poincaré classes of external potentials in its production and desctruction [

28]. Moreover, since Dirac dynamics under various external potentials can be simulated with trapped-ion setups or mapped onto bilayer graphene, this entanglement can be reinterpreted in terms of correlations between angular momentum quantum numbers in the former [

29], and lattice–layer quantum correlations in the latter [

30]. Another important instance of intrinsic entanglement arises in neutron interferometry, where the particle’s spin is entangled with its path from the source to the detector. This entanglement has been measured and used to reconstruct the density matrix of Bell states [

31].

In light of the above considerations, in this work we study the Dirac equation in a monochromatic quantized electromagnetic plane wave and a confining scalar linear potential. We first derive the exact wave functions and equation giving the energy spectrum, then use these solutions to analyze how particle–field interactions affect the quantum entanglement between the particle’s spin and the remaining degrees of freedom.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we derive the exact solutions of the Dirac equation and examine their limit when the particle–field interaction is switched off. In

Section 3, we review negativity and Von Neumann entropy as entanglement measures and apply them to correlations between the particle’s spin and the remaining degrees of freedom. In

Section 4, we present our conclusion.

2. The Dirac Equation

Consider a Dirac particle, with a charge

and a rest mass

m, moving in the

plane in the field of a Lorentz scalar linear potential

, with

being a real positive parameter and interacting with the quantized field of a monochromatic electromagnetic plane wave. Specifically, we assume that the electromagnetic field is linearly polarized along the axis

x and propagates along the

y-direction, so that, in the Coulomb gauge, it is represented by the vector potential

, with

being the unit polarization vector. The dynamics of the particle is then described by the equation

where

is a four-component wave function and

are the Dirac matrices. Note that throughout this paper we will be using natural units in which

. The operator-valued potential

can be written as

where

V is the quantization box volume, and

a and

are annihilation and creation operators of a photons with angular frequency

, respectively, satisfying the commutation relation

. Then, in order to exclude the variable

from the vector potential operator, we make the unitary transformation

, where

is an unknown four-component function. Injecting this into Equation (

1), multiplying the latter from the left by

, and using the operator identity

leads to the following equation for

with

. Now, since each of the two variables

t and

y appears in Equation (

4) only as a derivative, it is natural to seek a solution for this equation in the form

, where

and

are constants and

is a four-component function independent of

t and

y. In fact, as will become clear below,

represents the energy of the particle–photon system and

is the component of the total momentum along the

y-axis. Moreover, it will be wise to decompose

as

where

(for

k = 1, 2, 3) denote the Pauli matrices and

and

are unknown two-component functions. After substitution into Equation (

4), and by working in the Majorana basis, one obtains the following equations

with the abbreviations

. The advantage of the Majorana basis becomes clear here, given the simplicity of Equation (

7), which provides a direct expression of

in terms of

. On the other hand, the elimination of

in favor of

results in the equation

We thus have two decoupled equations for the two components of

, and our next task is to construct the exact solutions of these equations. To do this we will use the “momentum” representation for the operators

a and

:

In this way Equation (

8) becomes

where we have introduced the dimensionless variable

. In light of Equation (

10), the function

will depend on both the variable

, i.e., the coordinate of the particle, and on the field variable

q. The same also goes for the function

. We handle Equation (

10) by transforming it to new variables

where

,

,

, and

are constants to be determined by requiring that the variables

u and

v separate in the transformed equation. After a lengthy but straightforward calculation we find that one can actually achieve this result by choosing

With these choices, Equation (

10) takes the form

with the notations

and

. In the non-interaction case (

), we have

for

, and

for

. Note that, in the limit

, the

problem should separate, as can be inferred from Equation (

10). On the other hand, it follows from Equations (

13) and (

14) that the form of the solutions of Equation (

10) depends crucially on whether or not

is real and

. For

, we readily verify that

is always real and less than one. However, for

, elementary calculations (see

Appendix A) show that these conditions fail within

implying the appearance of a forbidden energy region due to the particle–field interaction, which disappears when the interaction is switched off.

Then, for real

and

, introducing the new variables

and

, with

casts Equation (

13) into the canonical form

with

. Moreover, we can show that

, which is useful for deducing the non-interaction case as

. Equation (

17) shows that all the effect of the interaction between the particle and the field of the electromagnetic wave is contained in the quantity

. In the limit

, whether

or

, Equation (

17) reduces to two independent “harmonic oscillators”: one for the particle in the scalar linear potential and one for the quantized field. Notably, the oscillator describing the particle for

corresponds to that of the field for

, and vice versa. This feature of the problem will be further commented on below. Subsequently, from Equation (

17) it results that the energy spectrum of the particle–photon system is determined by the equation

where

and

are two non-negative integers and

for the energy eigenvalues associated with

, the lower (upper) components of

. These latter are expressed in terms of Hermite polynomials

and they are given, up to multiplicative constants, by

Furthermore, it is clear from Equation (

18) that it is not possible, in the general case, to find solutions

where both

and

are non-zero and have the same energy. We thus have two distinct sets of solutions for Equation (

1): A first set, hereinafter denoted as

, for which

and the system energy is to be determined from Equation (

18) with

, and a second set, hereinafter denoted as

, for which

and the system energy is to be determined from Equation (

18) with

. More specifically, on the basis of the above, the complete expression of the wave functions

can be written as

and

where

are normalization constants and where we have used the following abbreviations

with

The wave functions

satisfy the orthogonality condition

with

and

being, respectively, the Dirac and the Kronecker delta functions. Thus, taking into account the standard orthogonality relation of Hermite polynomials, we find that the normalization constants

can be chosen as

Let us look at the behaviour of the wave functions

when the interaction between the Dirac particle and the field of the quantized electromagnetic wave is switched off. It is straightforward to verify that as

and

, we have

,

,

,

, and

, so that

reduce to the forms below

and

with

However, as and , we have , , , , and , such that reduce to the same forms as above with and interchanged and q replaced by .

Thus, in the limit

, the particle–photon wave function factorizes into the Dirac particle wave function in the scalar linear potential and the harmonic oscillator wave function. In this case, the states are eigenfunctions of the particle operators

and

, associated with its energy and

y-momentum, with eigenvalues

and

, respectively. They are also eigenfunctions of the operator

, associated with both the energy and the momentum of the monochromatic wave (remember that

), with the eigenvalue

. Hence,

and

represent, respectively, the total energy and the

y-momentum of the system. Note that

and

are conserved even when an interaction between the particle and the photon occurs, which is not the case for the individual operators

,

, and

. An interesting feature of the limit

is that, for

, the wave functions describe a particle in a level labeled by

and a state of the electromagnetic field with

photons, whereas for

, the wave functions represent a particle in the level

and a state of the electromagnetic field with

photons. However, in the interacting system, as shown in Equations (

20) and (

21), individual particle and photon states cannot be distinguished; only the entangled particle–photon state as a whole can be defined.

As for the energy, found via Equation (

18), in the limit

we obtain for

with

being the particle energy,

its

y-momentum, and

. For

, we obtain the same form as Equation (

26) but with

and

interchanged. These results coincide with the known energy spectrum of a Dirac particle in a scalar linear potential [

32].

Although not our main aim, it is worth commenting on the case where

is real but

. In this situation, the solutions of Equation (

13) can be written, up to constant factors, in terms of parabolic cylinder functions

as

where

and

are arbitrary real numbers. However, these wave functions are nonphysical because they cannot be normalized in the sense of Equation (

22), as this leads to divergent integrals. This fact can be easily verified given the asymptotic expansions of the function

for

,

and

[

33]:

3. Spin–Rest Entanglement

In this section, we investigate the effect of particle–field interaction on the quantum entanglement between spin on one side and the remaining (position plus field) degrees of freedom on the other. We restrict ourselves to

, the positive-energy branch of the light-front dispersion relation, where

plays the role of light-cone energy, ensuring a forward-propagating state. To quantify entanglement, we use negativity [

34,

35] and Von Neumann entropy [

25,

36]. Negativity is a measure based on the Peres–Horodecki (PPT) criterion, which states that a separable bipartite density matrix has a positive partial transpose [

37]. For a bipartite state

, Negativity is given by

where

are the eigenvalues of the partial transpose of

. Negativity also has a direct physical meaning as a count of the number of entangled dimensions between the system’s subsystems [

38]. Von Neumann entropy is a widely used entanglement measure for pure bipartite states. For a composite system

in a pure state

, it is defined as

where

is the reduced density matrix of subsystem

with eigenvalues

. By Schmidt decomposition,

and

share the same non-zero eigenvalues [

39].

The density operator

associated with the state

can be written as

with the following notations

where

denote normalized eigenstates of the 2D harmonic oscillator in variables

and

, and

The states

are not eigenstates of the spin operator in the Majorana basis but are related to them by a unitary transformation. Since

are orthonormal, we employ the basis

to construct the matrix of

. The partial transpose of

with respect to spin is obtained by interchanging ↑ and ↓ in the last two terms in Equation (

31). Note that transposing either subsystem yields the same eigenvalues and, hence, the same negativity. On the other hand, the reduced spin density matrix is obtained by tracing out the (position + field) degrees of freedom. This gives

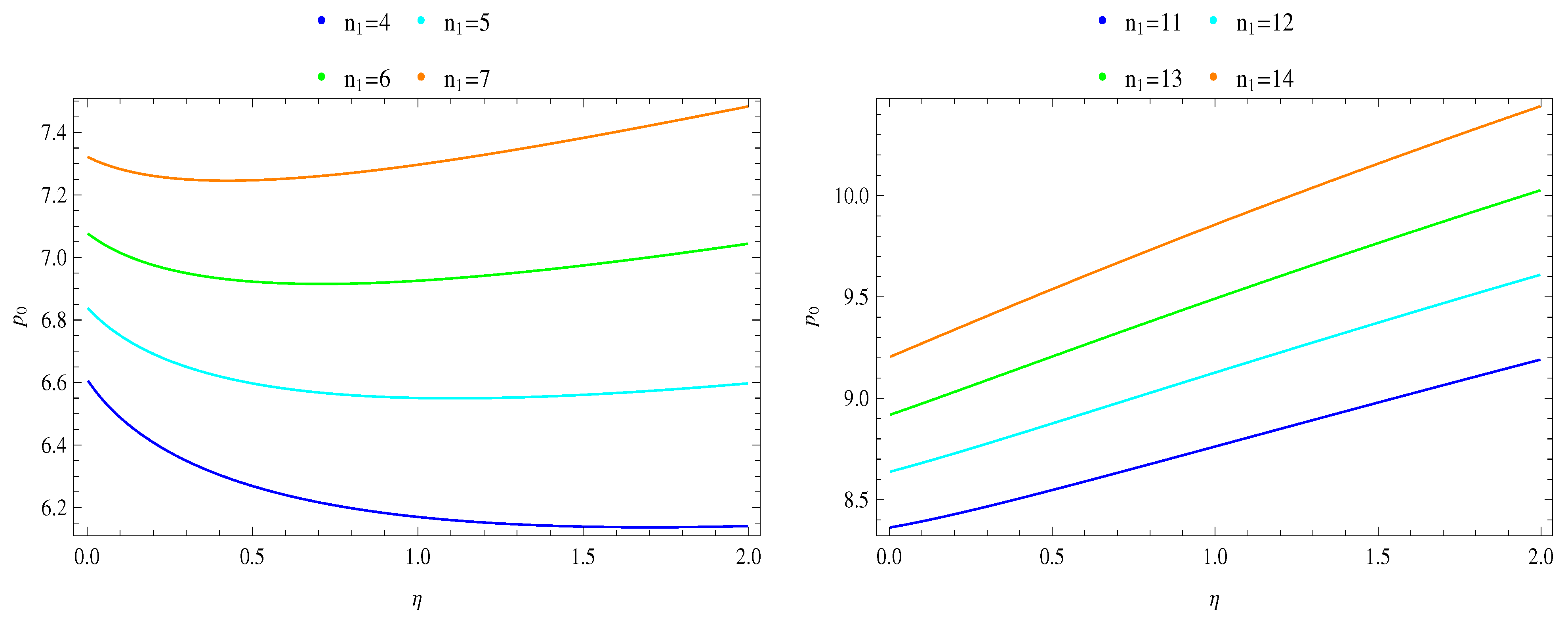

In

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, we show the variations in the negativity

N and the Von Neumann entropy

E with the coupling parameter

for illustrative states, while

Figure 3 displays the corresponding total energies. For states with monotonically increasing energy in

, both

N and

E also rise monotonically: the spin undergoes smooth hybridization with the orbital-field modes, leading to increasing correlations. Since the spin is a two–level system,

N and

E are bounded above by

and

, respectively. Once the reduced spin state approaches the maximally mixed limit, further coupling cannot increase entanglement, and both

N and

E saturate. However, for states whose total energy is non-monotonic in the coupling,

N and

E first rise with

, approach their limiting values, and then decrease as

increases further. This resonant behavior of the entanglement arises from the competition between the Lorentz scalar linear potential and the external field; for these states,

Figure 3 shows that at small

the external field pulls the energy downward, so the energy initially decreases before rising again. The slower this recovery, the sharper the entanglement resonance. Notably, the spin becomes maximally entangled with the rest of the system at a lower coupling

. This behavior resembles the spin–boson model, where in the symmetric case the entanglement grows monotonically with coupling until maximal, while in the asymmetric case it peaks at an intermediate value before decreasing [

40].