1. Introduction

The United States has long relied on a vast and interconnected transportation system—which has evolved through our history with the decline of railroads but an increase in reliance on our vast interstate, highway, state, and local roadway system to support the economy and connect goods, services, and people across its large and diverse landscape [

1]. As this network continues to evolve in response to technological advancements and shifting societal needs, ridesharing has emerged as a technological disruption within the mobility sector [

2,

3]. Although personal vehicles have traditionally dominated ground transportation, the growth of rideshare services is reshaping how people travel [

4,

5,

6]. Gaining a deeper understanding of these changes, particularly the distinctions between personal and pooled rideshare services, is essential for anticipating the direction of future transportation systems in the U.S. [

7].

Ridesharing offers on-demand transportation via digital platforms. The basic service of ridesharing is “arranging one-way transportation on short notice” [

8], connecting passengers with drivers through smartphone applications [

9,

10]. This model, popularized by Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) such as Uber and Lyft [

7], has rapidly increased, offering a customized and convenient transportation solution. However, it is important to distinguish between personal rideshare and pooled rideshare services—terms often used interchangeably but representing different experiences [

11]. Personal rideshare (also known as ride-hailing) provides direct point-to-point service for a single rider or group of riders who know one another, while pooled rideshare involves sharing a ride with a single or multiple passengers traveling in similar directions who do not know one another [

12]. Although TNCs offer both options, most rideshare trips use personal rideshare.

Rideshare services are parallel and diverge from traditional transportation, which is notable in several ways. For instance, taxi services require “roadside hailing”, whereas rideshare platforms offer pre-scheduled pick-ups and cashless transactions [

13]. Unlike carpooling, which often requires pre-planning, ridesharing dynamically matches riders and drivers in real time, offering greater flexibility [

14]. Furthermore, environmental and societal implications are notable, as these services can contribute to decreased traffic congestion and a positive environmental impact [

11,

15].

To fully understand the current state of ridesharing, a brief look at its history is essential. Although the concept of sharing rides, such as jitney services, dates to the era of the Ford Model T [

16,

17,

18,

19], the modern iteration of ridesharing is closely linked to technological advancements [

20]. The proliferation of smartphones and internet access outside the home or office created the foundation for real-time ride matching and efficient communication between drivers and riders [

21,

22]. The inspiration for Uber, the largest company in the rideshare industry, originated in 2008, when two friends struggled to find a taxi in Paris [

23]. Their initial idea evolved into a service provider using a smartphone app. As of 2025, Uber operates in approximately 70 countries and more than 10,000 cities worldwide, with a market capitalization of around

$160 billion [

24]. Lyft, another major service provider, followed in 2012, increasing the mainstream adoption of app-based mobility [

25]. Apart from Uber and Lyft, numerous ridesharing platforms are available worldwide, such as DiDi in China [

26], Ola Cabs in India [

27], Grab in Southeast Asia [

28], and Chauffeur Privé in France [

29]. Uber offers services worldwide and is the largest ridesharing service provider.

While ridesharing has become a global phenomenon, it is important to recognize the unique challenges that exist within the United States compared to other countries [

30,

31]. Ridesharing services have been more seamlessly integrated into many international markets with longstanding multimodal public transportation networks and urban planning efforts. In contrast, the U.S. relies predominantly on personal vehicles. Coupling personal vehicle use, reliance on a suburban lifestyle, and limited public transit infrastructure outside major metropolitan areas [

32], these conditions create different expectations and demands from U.S. consumers. Additionally, regulatory policies vary widely across the U.S., leading to varying user experiences and operational hurdles for TNCs, which may not be as prevalent in more centralized regulatory systems in other countries [

31]. Understanding these unique dynamics is critical when examining the reasons behind the lack of widespread use of pooled rideshare adoption within the United States.

The growth of rideshare use has not been without its challenges [

33,

34]. While riders benefit from flexibility, affordability, and decreased impaired driving incidents, key concerns—particularly with pooled rideshare—persist [

35]. Pooled rideshare adoption continues to face user concerns that cause reluctance in widespread acceptance. Safety is a primary issue, with many users hesitant to share rides with strangers due to fear concerning their physical security and/or the unpredictability of fellow passengers as well as the driver (these concerns may be related to the lack of background checks and/or screenings) [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Topics related to the ride’s service and/or experience are another area of concern, particularly around the consistency and reliability of pick-ups, drop-offs, and the vehicle’s cleanliness [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Privacy is often cited as a barrier, as pooled rides require passengers to share confined spaces [

48] and personal travel details such as pick-up and drop-off locations with strangers [

49]. Pooled rides can also take longer due to multiple stops, leading to concerns about the efficiency of one’s time as well as the overall convenience of these services [

50]. Trust in both the rideshare platform and the driver is critical. Riders must feel confident that the driver is safe, professional, and respectful of riders’ preferences [

51,

52]. These topics collectively shape the perceptions of pooled rideshare and highlight areas where service providers may improve their services to enhance ridership.

Despite these challenges, ridesharing continues to evolve, with TNCs consistently exploring enhanced services to address user concerns [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. As rideshare services grow their presence in the U.S. transportation sector, understanding how users view their multifaceted aspects becomes increasingly important. Understanding the TNCs’ pooled rideshare services, as well as their associated benefits and concerns, requires a comprehensive analysis. By examining the different rideshare-associated topics, policymakers, transportation planners, and other stakeholders can work towards building a future where pooled rideshare contributes to a more efficient and effective transportation system for all.

Previous Nationwide Study on Pooled Rideshare

The current study builds upon and extends the findings of a nationwide survey conducted in 2021, which included 5385 respondents, with 3385 participants from seven major U.S. cities and an additional national sample of 2000 participants. The objective of the 2021 survey was to create a baseline understanding of pooled rideshare within the transportation sector. The survey responses revealed trends in transportation preferences and usage, barriers, and motivators influencing the willingness to consider pooled rideshare services [

59]. The study employed a mixed-methods approach that integrated qualitative insights with quantitative data. Initially, open-ended responses were analyzed to capture users’ concerns and experiences related to pooled rideshare.

The results from the 5385 participants were used to conduct two separate factor (including exploratory and confirmatory) analyses to identify latent constructs that influence pooled rideshare adoption [

60,

61]. The first factor analysis focused on identifying factors influencing one’s willingness to consider pooled rideshare, resulting in five major factors: safety, service experience, privacy, time/cost, and traffic/environment [

60]. The second factor analysis explored how to optimize the user’s experience so that the user may be willing to consider pooled rideshare, and identified four factors: comfort/ease of use, convenience, vehicle technology/accessibility, and passenger safety [

61]. Logistic regressions revealed how each of the factors individually can influence one’s willingness to consider pooled rideshare. Privacy concerns, for instance, were found to reduce the likelihood of pooled rideshare adoption by 77%, while convenience can increase it by 156%. These nine factors formed the conceptual backbone for further modeling efforts.

Next, the goal was to determine their contribution to the adoption of pooled rideshare when evaluating all the factors together. To understand the relationships among these factors, the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) was developed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [

62]. This model assessed how each of the nine factors contributed to outcomes, including trust in pooled rideshare services, user attitudes, and behavioral intent to use pooled rideshare. Among the factors, privacy, safety, trust in the service, and convenience had a strong significant influence on the PRAM, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s f

2 > 0.35), along with the significance of comfort/ease of use, service experience, traffic/environment, and passenger safety factors. Notably, while time and cost were not significant on their own, their influence was indirectly included under the context of convenience and service reliability.

Recognizing that transportation preferences are not uniform across populations, another set of analyses extended PRAM into the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analyses (PRAMMA) [

63]. This stage of analysis incorporated 16 demographic moderators—such as gender, age, generation, income, education, geographic area, and prior rideshare experience—to explore subgroup differences. The multigroup analyses confirmed the need for tailored strategies for different groups of users. For instance, privacy concerns were especially critical for female participants, while younger participants placed more emphasis on environmental and technological benefits. Frequent riders showed higher tolerance for shared rides and stronger trust in the platform.

Drawing from these results, the research team translated statistical insights into 84 actionable items that may be used to address barriers to pooled rideshare [

59]. These items were developed through a series of workshops. The actionable items were categorized thematically into key domains, including vehicle selection, routing, driver and passenger characteristics, safety, user experience, and educational services. Each recommendation was derived from empirical data, ensuring the actionable items were grounded in user-centered design principles. The data-driven process used in this series of studies provides the foundation for this manuscript.

This study aims to provide a nationwide perspective of potential modifications and features that may increase pooled rideshare usage in the United States. Building on findings from a previous nationwide survey and the development of 84 actionable items, this follow-up research uses a large national sample to assess how participants respond to specific pooled rideshare service enhancements across multiple categories. Comparing users’ willingness to use pooled rideshare before and after rating the actionable items serves as an initial step to identify the most impactful strategies that may be adopted by Transportation Network Companies (TNCs), policymakers, and urban planners, etc., to increase pooled rideshare adoption. This exploratory study, using a broad national sample, may provide a foundation for future targeted efforts to build upon the most promising actionable items. Since this is an exploratory study, a pre–post comparison is used by asking participants about their willingness to use pooled rideshare before and after reviewing the actionable items to determine if exposure to these topics influences participants’ ratings.

4. Discussion

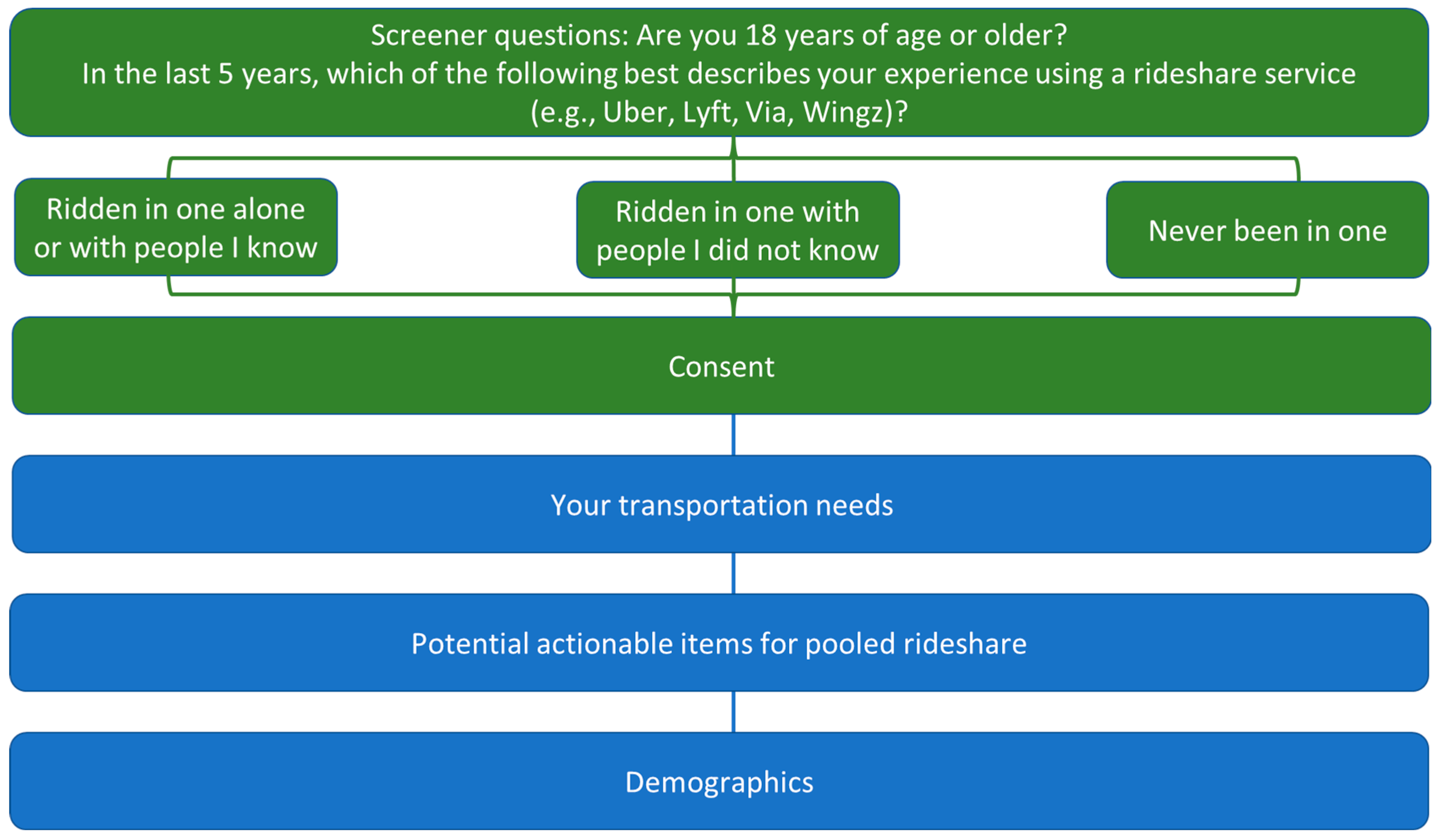

This study is exploratory in nature and focuses on the descriptive analysis of 8,296 participants’ survey responses to understand their transportation behaviors, rideshare experiences, and pooled rideshare preferences. By examining participants’ responses across multiple transportation modes, including personal vehicles, personal rideshare, and pooled rideshare, the study provides insights into shifting mobility patterns, key items influencing pooled rideshare adoption, and the impact of external factors. In addition to analyzing current behaviors and preferences, the study introduced a set of 77 actionable items aimed at addressing user concerns to potentially improve pooled rideshare experiences. By comparing willingness to use pooled rideshare before and after exposure to these actionable items, the study assessed the actionable items’ potential effectiveness in influencing user perceptions regarding pooled rideshare.

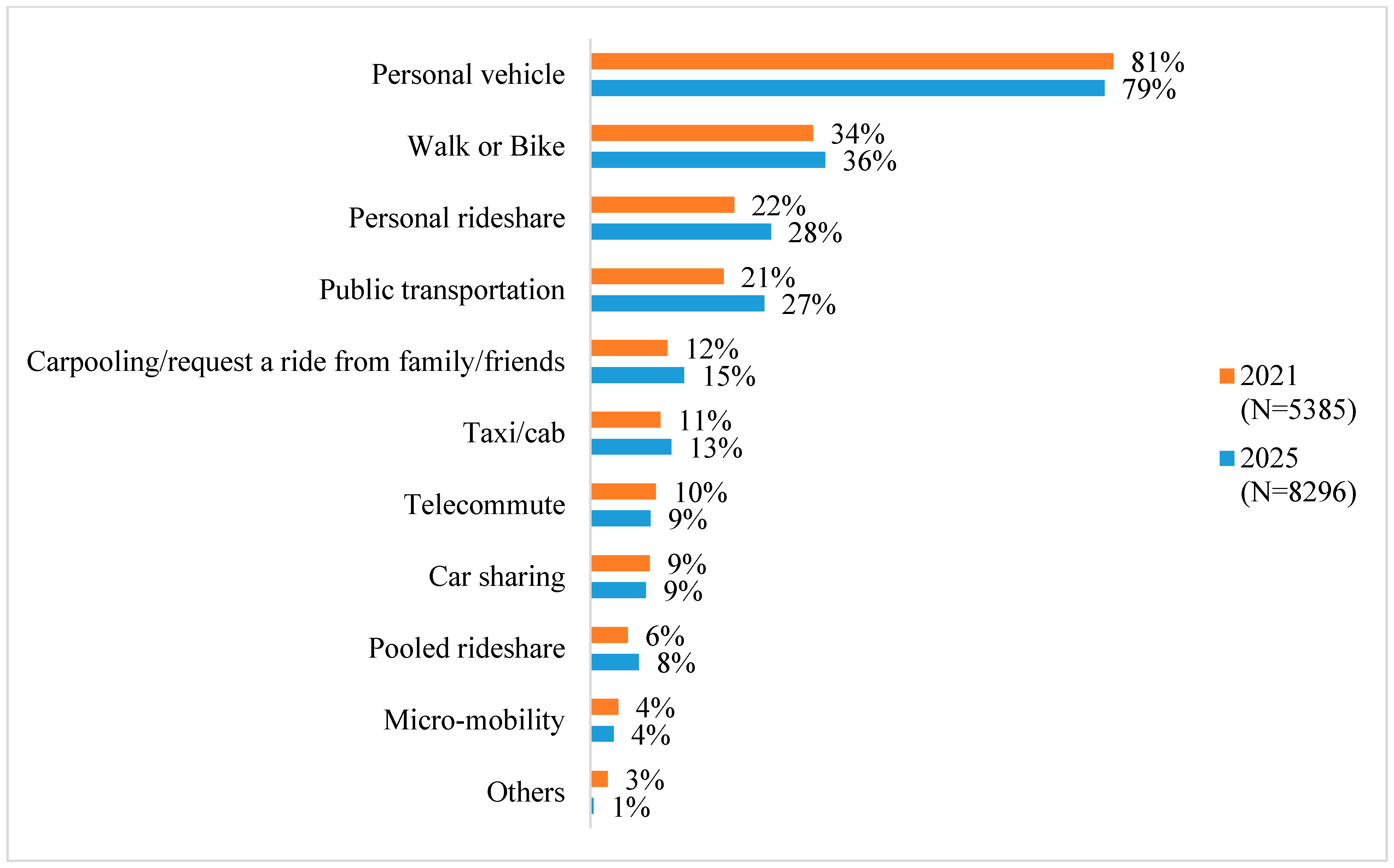

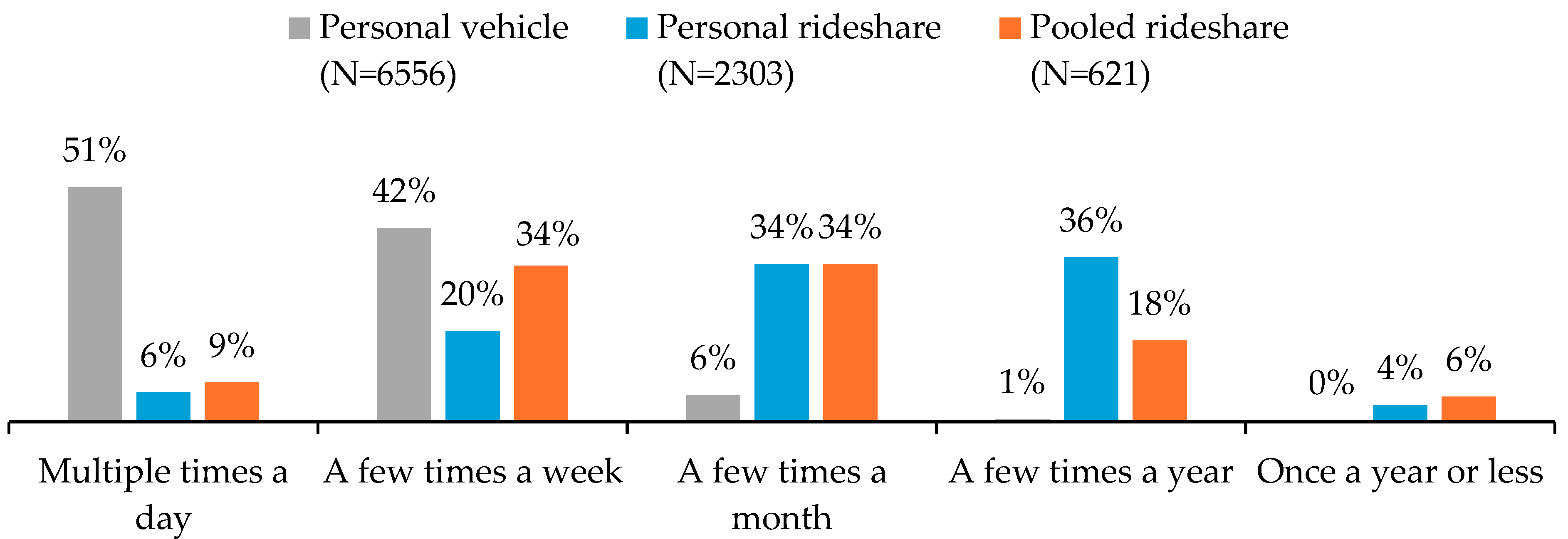

The findings of this study highlight shifts in transportation behaviors and rideshare adoption over time (2021 vs. 2025). Notably, the use of personal rideshare services has grown, with usage increasing from 22% to 28%, while the use of public transportation has also increased from 21% to 27%. These trends indicate a growing reliance on or return to shared mobility solutions. Personal vehicle use remains dominant, with 79% of respondents still favoring private transportation. The increased use of pooled rideshare services for essential trips, such as airport transportation and errands, suggests a shift toward integrating rideshare into routine mobility rather than just social or leisure travel. While a decline in pooled rideshare participation was observed for work-related travel and social outings, this may be an artifact in the data, since the new category of large events was added as an option. While personal and pooled rideshare services are used regularly, their frequency of use remains lower compared to personal vehicle use. Personal vehicles are overwhelmingly the primary mode of transportation, with most users driving multiple times a day or at least a few times a week. In contrast, personal and pooled rideshare services are more often used on a situational basis, typically a few times a month or a few times a year.

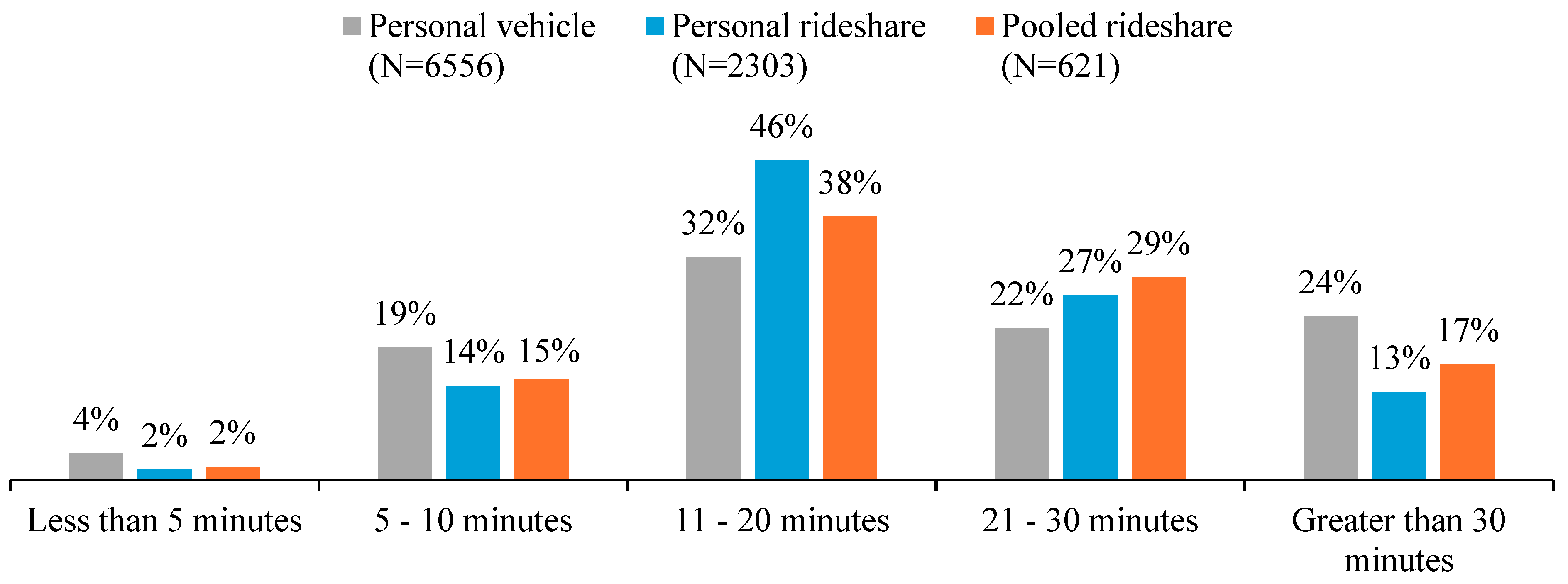

Cost remains a distinguishing factor, with pooled rideshare fares generally lower than personal rideshare fares, highlighting its service as a budget-friendly alternative. However, pooled rideshare users tend to have longer trip durations compared to personal rideshare users, and this may be partially due to the additional time required for multiple pick-ups and drop-offs. This trade-off between cost savings and travel time efficiency continues to be an important consideration for users when selecting a rideshare option.

Next, to understand the factors influencing participants’ willingness to use pooled rideshare services, the study examined 77 actionable items.

Table 10 includes all 70 of the 77 actionable items that showed importance (combined across “strongly agree” and “agree”) to more than half of the respondents. Among all the actionable items, those related to verification and security were rated of the highest importance, with more than 90% of participants agreeing that having the driver’s name and photo, displaying vehicle details such as make, model, and license plate number, and implementing a two-way verification code system are essential for ensuring trust and safety. Similarly, providing a reliable service during peak demand times and allowing users to save the most money and time on their trips were equally important, indicating that users prioritize dependability and efficiency in their pooled rideshare experiences. In addition to security and reliability, driver selection criteria were highly rated, with more than 90% of respondents emphasizing the need for clean driving records, high punctuality ratings, recent background checks, and high passenger ratings. This suggests that users are highly selective regarding who operates their rideshare experience. Vehicle cleanliness and accessibility are highly relevant, with the expectation that pooled rideshare providers should maintain excellent hygiene standards and ensure vehicles are easy to enter and exit.

Topics that fall between 80 and 90% include trip planning, personalization, and customer experience features. Users want faster pick-ups at airports and transit hubs, the ability to book roundtrips in one transaction, and clear pick-up/drop-off zones for large events. Additionally, discounts and price fixation for pre-booked trips, reward programs for frequent riders, and the ability to book recurring trips in advance were highly favored, indicating that pricing incentives and convenience features can further influence pooled rideshare use. Real-time trip tracking and emergency contact options play a crucial role in increasing user confidence in pooled rideshare services.

Several actionable items fell within the 70–80% agreement range. Many of these topics focus on features that enhance ride efficiency, personalization, and inclusivity. The ability to store frequently used destinations and set maximum detour times is valued, suggesting that users desire control over their trip logistics. Additionally, options to choose a conversation-friendly or quiet ride, consult with the driver regarding the temperature and music settings, and transparency on passenger pick-up/drop-off locations were seen as beneficial, but not as universally essential as safety and cost-related topics. A free trial ride for first-time users and ensuring that elderly passengers have access to pooled rideshare services were also supported, indicating that targeted promotions and inclusivity measures can positively influence adoption.

Many additional actionable items, while still relevant, were of lower importance (50–70%). Some of these topics include environmental savings calculations, partnerships with major employers for pooled rideshare incentives, and connectivity features like Wi-Fi and charging ports. Similarly, preferences for fragrance-free vehicles, pet-friendly options, and luxury vehicle choices were of value to some, but certainly not most of the users.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Seven items were not valued by the full group of participants, and these items have 50% or less of respondents selecting “strongly agree” or “agree” (

Table 11). Offering beverages or snacks during a pooled rideshare trip was the least valued item, followed by the inclusion of a child and/or booster seat and having a driver of the same gender. The four other low-rated items include passengers who are of the same gender or a similar age, accessibility features such as accommodating wheelchairs, walkers, or assistive devices, and services for unaccompanied minors. Future research should examine many of these items based on targeted subgroups, because their actionable items are anticipated to be valued differently. For example, parents with young children may value booster seats, while parents with young teens may value services specifically for young teenagers who are too young to drive. It is not surprising that only 42% of the sample supports having a child or booster seat, considering that 59% of the participants do not have children. Future efforts should also examine what makes unaccompanied minors using a pooled rideshare comfortable and uncomfortable. The same applies to riders who use assistive devices, a walker, or a wheelchair.

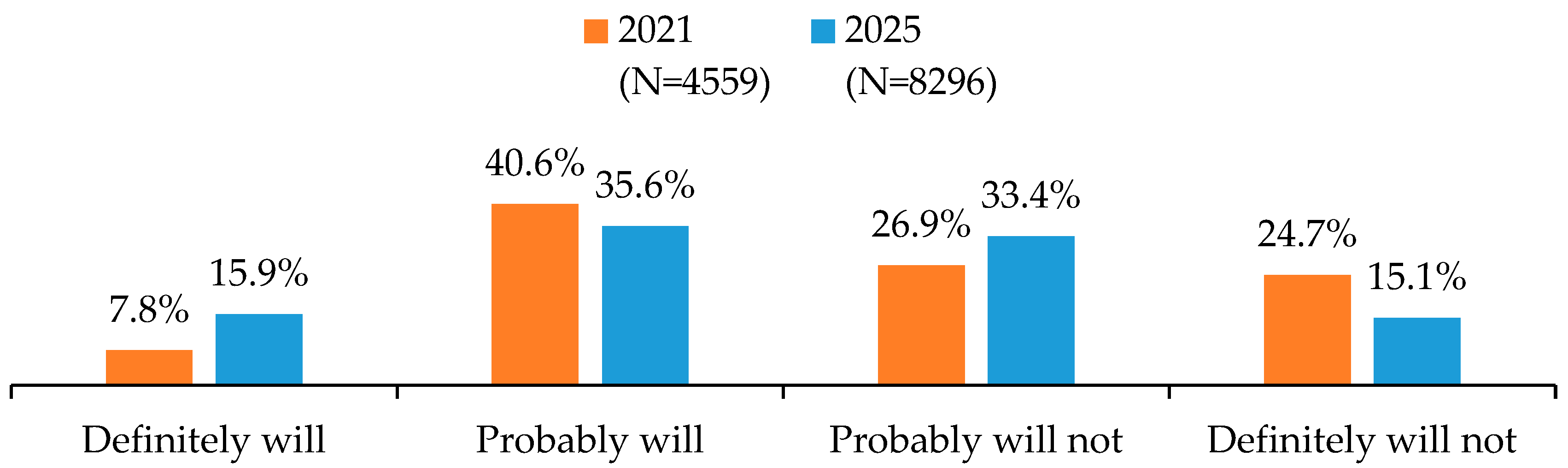

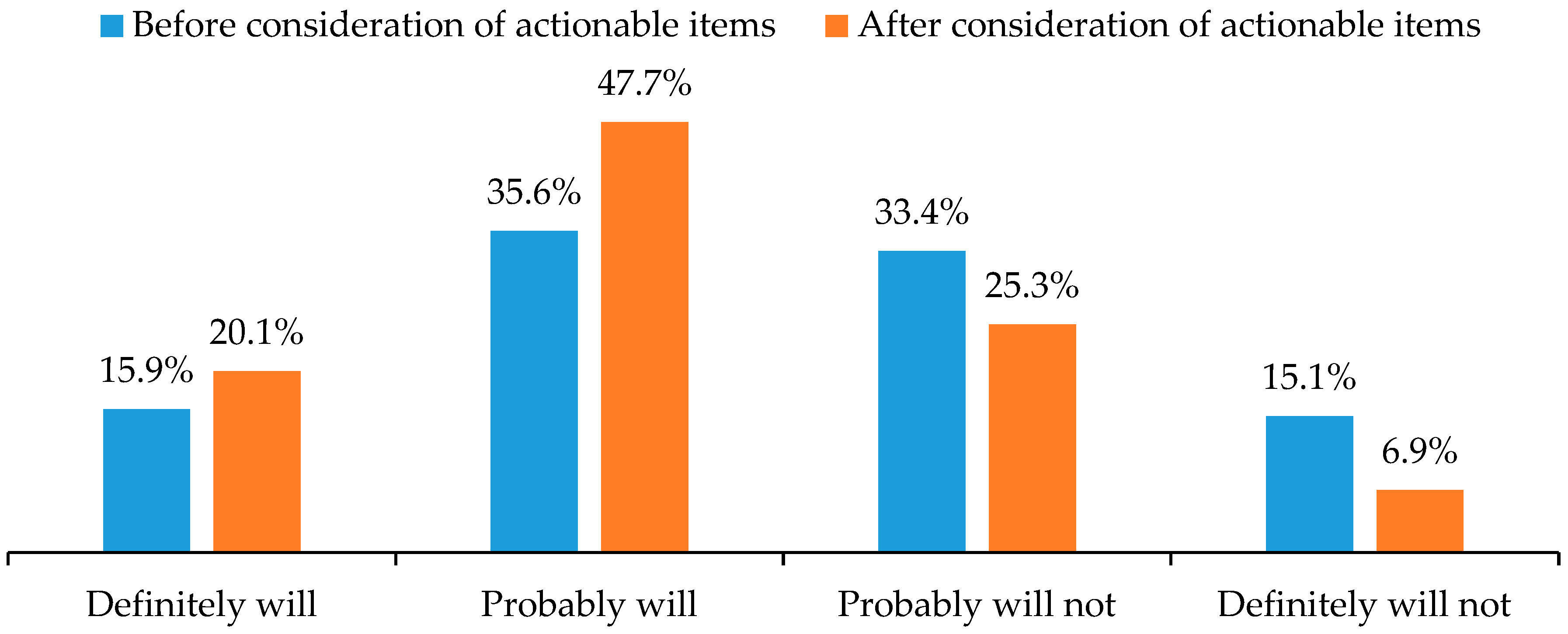

This study assessed the potential effectiveness of the proposed actionable items by comparing willingness to use pooled rideshare before and after exposure to these 77 items. This simple pre–post comparison indicates a positive shift in willingness to use pooled rideshare, with the proportion of participants who responded “definitely will” increasing from 15.9% to 20.1% and those selecting “probably will” rising from 35.6% to 47.7%. Meanwhile, reluctance to use pooled rideshare decreased, as those who selected “probably will not” declined from 33.4% to 25.3%, and “definitely will not” dropped from 15.1% to 6.9%. These findings suggest that addressing users’ concerns through targeted improvements may increase the likelihood of pooled rideshare adoption, yet these differences may be partially due to study participants recently reading the actionable items. It will be valuable to have longitudinal data to see how participants’ views and actual rideshare usage changes over time as actionable items are introduced to the market.

Future analyses should explore specific demographic variables, such as age. It is well known in the automotive field that Gen Z is not as excited to drive as previous generations [

65,

66,

67]. A deeper dive into that generation may provide generation-specific recommendations. The growing retired demographic [

68,

69,

70] may also have generation-specific preferences that deserve special attention. As vehicle prices are expected to increase due to tariffs and increases in the cost of automotive components [

71], increases in pooled rideshare may follow. Future efforts should be made to share the utility of the recommendations that are incorporated by TNCs or municipalities.

The goal of this study was to gain a wide national view of pooled rideshare. While pooled rideshare increases with population densities, this study’s sample is largely represented by suburban (50.3%) and rural (19.1%) participants compared to urban (29%) populations, where pooled rideshare is typically more prevalent. Future analyses should compare the results from urban and suburban markets.

While this study compares two independent groups of participants from 2021 and 2025, a longitudinal study including participants from different generations and locations will be beneficial. A longitudinal study will not only allow for comparisons of transportation behaviors across time, but also nuanced perspectives from different geographical regions. A longitudinal study will allow for understanding how parents’ needs change as their children age, but also the different transportation needs of the growing aging population. A longitudinal study will be especially valuable to ensure that users with disabilities receive equitable services across their lifespan.

In addition, this study lays the foundation for promising directions for future research for modeling perspectives. First, the results from this study offer an opportunity to apply the new dataset to the previously developed Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) and its extension, Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analyses (PRAMMA), to examine whether factors such as privacy, safety, and convenience continue to most strongly influence pooled rideshare. With over 8000 participants, this new dataset can support more robust statistical models that may refine or expand upon the existing theoretical constructs. Therefore, future analytical phases of this research can incorporate formal statistical modeling, including estimates of variability such as confidence intervals.

Future research should also move beyond survey-based evaluations to real-world applications by conducting pilot programs, field experiments, or collaborations with Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) to observe the practical adoption and effectiveness of the key actionable items. It will also be important to evaluate many of the actionable items in locations using self-driving vehicles [

72]. Together, these steps will help bridge the gap between user-centered research, policy, and/or industry-level decisions that support the growth of pooled rideshare.

6. Conclusions

This exploratory study investigated pooled rideshare preferences among 8296 participants. The study evaluated 77 actionable items designed to address known barriers to rideshare acceptance, such as safety, service reliability, privacy, and convenience. Through a descriptive and comparative analysis, the results revealed that security-related features such as verified driver and vehicle information, emergency contact tools, and trip tracking were among the most valued, with over 90% of respondents agreeing on their importance. Users also expressed strong preferences for reliable service during peak demand (93%), the ability to save time and money (92–93%), and driver-related attributes like clean driving records and high ratings (92%). While vehicle cleanliness and ease of access were similarly important (92–93%), features like in-vehicle refreshments (41% agreed), booster seats (42% agreed), and demographic-based matching with passengers or drivers (46–50% agreed) were among the least valued.

The study demonstrated that presenting participants with potential targeted service improvements led to a notable increase in willingness to use pooled rideshare. The percentage of participants who responded “definitely will” increased from 15.9% to 20.1%, and those who chose “probably will” rose from 35.6% to 47.7%. These findings suggest that addressing users’ concerns through thoughtful and targeted improvements can enhance pooled rideshare adoption. By identifying which features matter most to users, this study offers practical guidance for Transportation Network Companies and policymakers aiming to improve pooled rideshare.