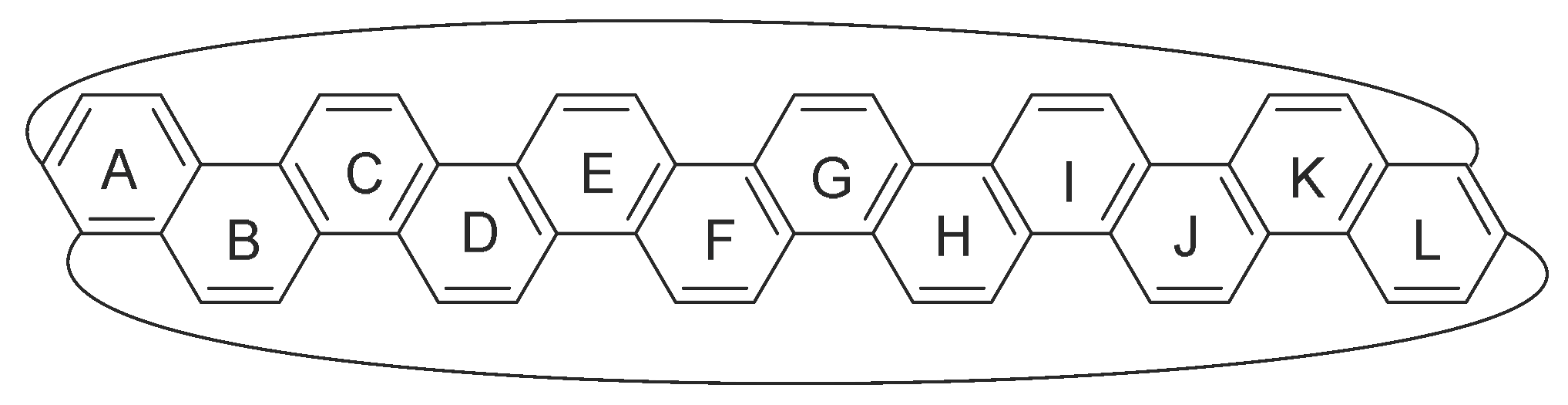

Aromaticity Study of Linear and Belt-like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

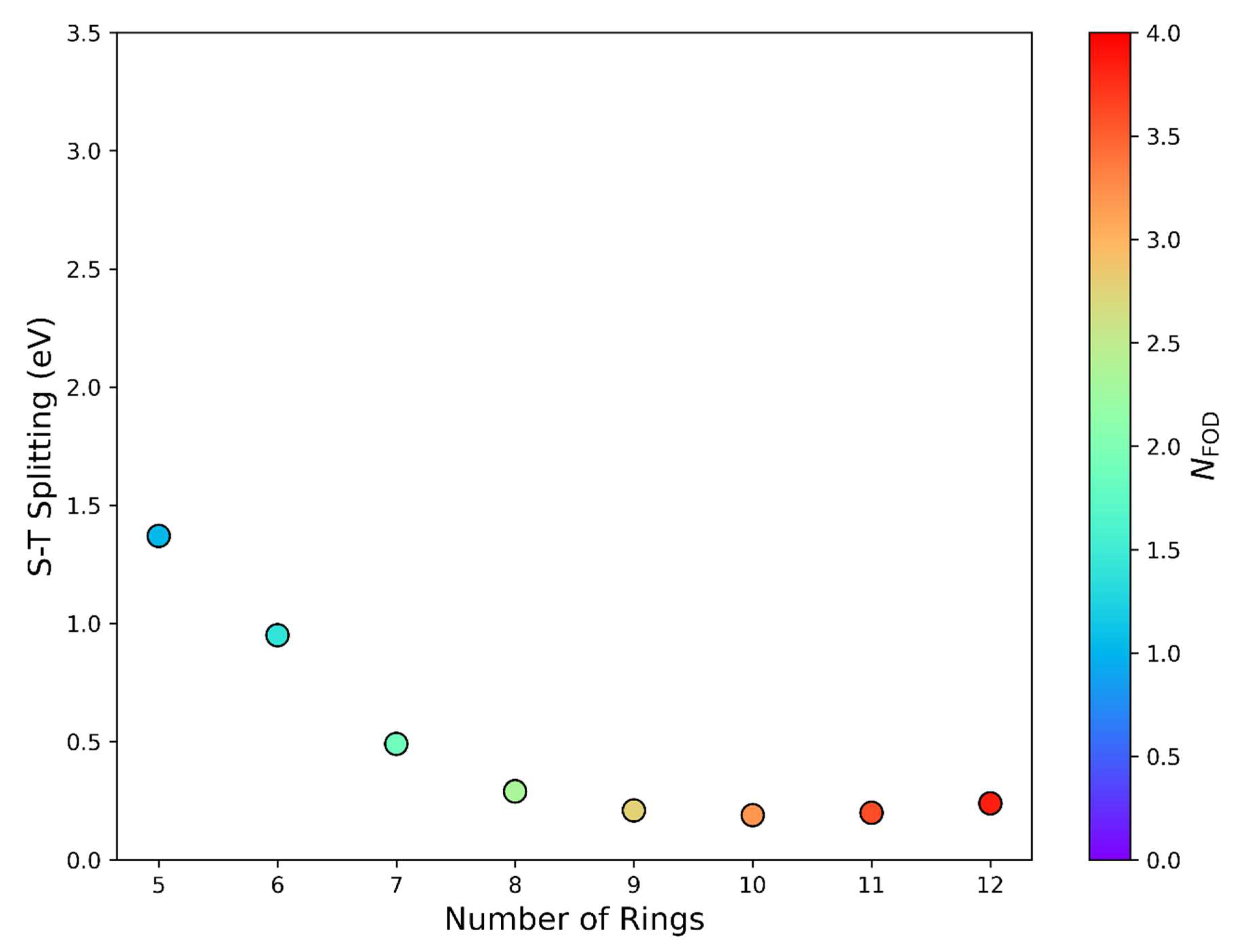

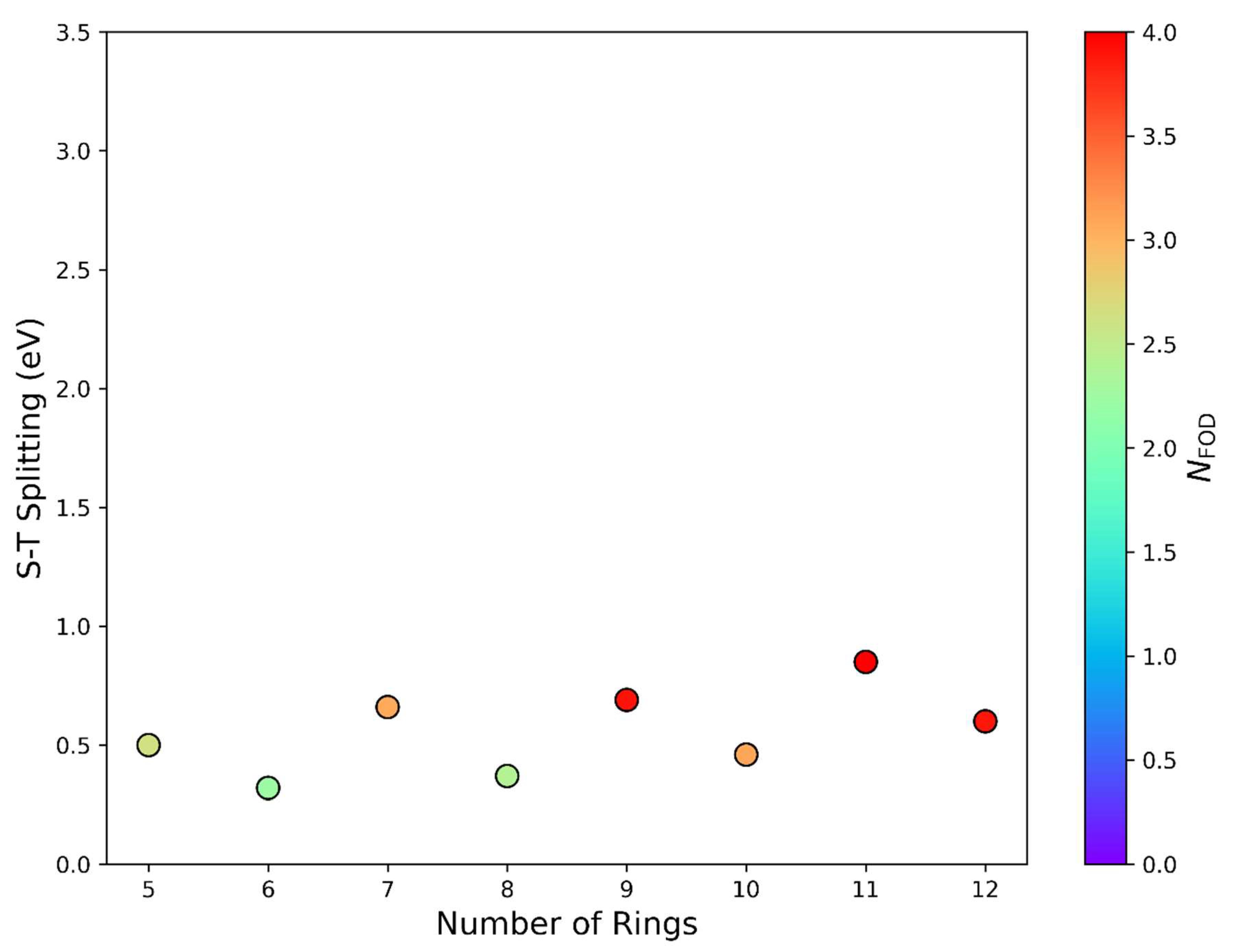

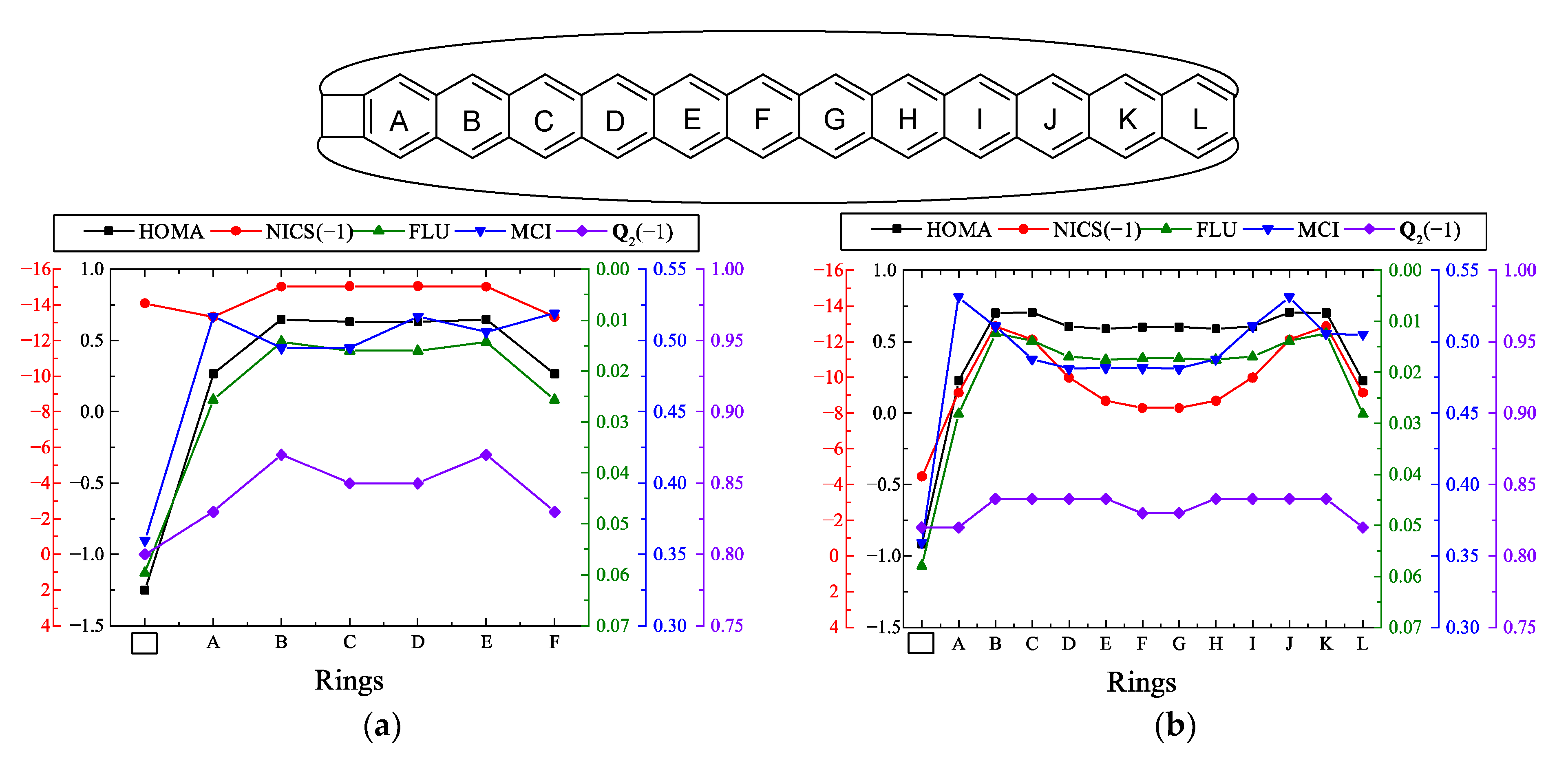

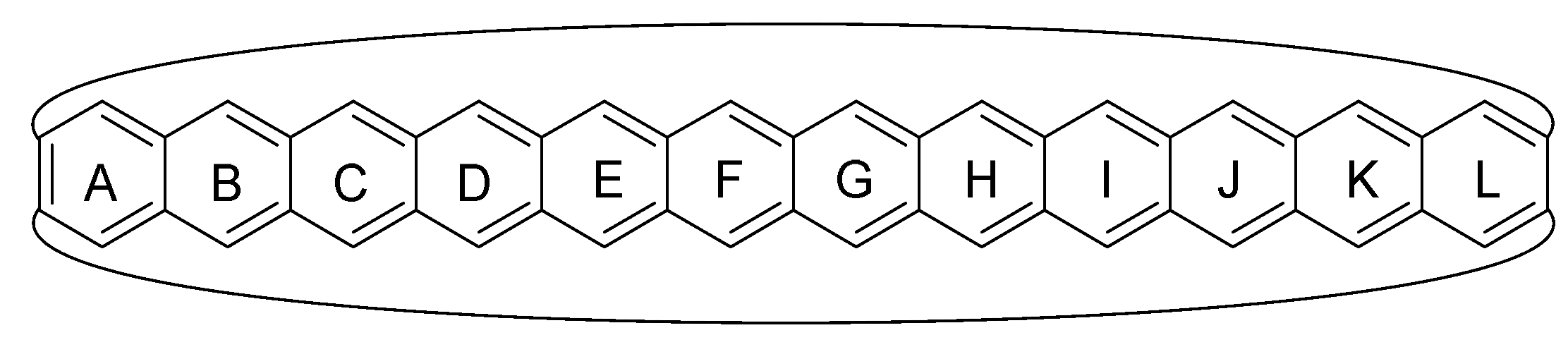

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, X.; Pisula, W.; Müllen, K. Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Synthesis and Discotic Organization. Pure Appl. Chem. 2009, 81, 2203–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ruffieux, P.; Jaafar, R.; Bieri, M.; Braun, T.; Blankenburg, S.; Muoth, M.; Seitsonen, A.P.; Saleh, M.; Feng, X.; et al. Atomically Precise Bottom-up Fabrication of Graphene Nanoribbons. Nature 2010, 466, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.; Carbonell-Sanromà, E.; de Oteyza, D.G. Bottom-Up Fabrication of Atomically Precise Graphene Nanoribbons. In On-Surface Synthesis II; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 113–152. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, T.H.; Shekhirev, M.; Kunkel, D.A.; Morton, M.D.; Berglund, E.; Kong, L.; Wilson, P.M.; Dowben, P.A.; Enders, A.; Sinitskii, A. Large-Scale Solution Synthesis of Narrow Graphene Nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, J.E. Functionalized Acenes and Heteroacenes for Organic Electronics. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5028–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokuchi, H. The Discovery of Organic Semiconductors. Its Light and Shadow. Org. Electron. 2006, 7, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Huang, L.; Gu, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Müllen, K.; Gu, C.; Ma, Y. Electrochemical Synthesis, Deposition, and Doping of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2682–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Hu, W.; Dong, H. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Based Organic Semiconductors: Ring-Closing Synthesis and Optoelectronic Properties. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2022, 10, 2411–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, G.R.; Dufourg-Madec, M.-B.; Crouch, D.J.; Pritchard, R.G.; Ogier, S.; Yeates, S.G. High Performance, Acene-Based Organic Thin Film Transistors. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3059–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.D.; Hu, H.; Wong, F.-L.; Lee, C.-S.; Chen, W.-C.; Feron, K.; Manzhos, S.; Wang, H.; Motta, N.; Lam, Y.M.; et al. Acene-Based Organic Semiconductors for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes and Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2018, 6, 9017–9029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Rocca, D.; Baroni, S.; Gubbins, K.E.; Nardelli, M.B. Molecular Design of Photoactive Acenes for Organic Photovoltaics. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 194701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Rios, R.; Báez-Grez, R.; Solà, M. Acenes and Phenacenes in Their Lowest-Lying Triplet States. Does Kinked Remain More Stable than Straight? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 13574–13582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Yamada, H. Exploring the Chemistry of Higher Acenes: From Synthesis to Applications. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 11204–11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixas, F.; Matito, E.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. Quantifying Aromaticity with Electron Delocalisation Measures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6434–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matito, E.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. The Aromatic Fluctuation Index (FLU): A New Aromaticity Index Based on Electron Delocalization. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygowski, T.M.; Cyrański, M.K. Structural Aspects of Aromaticity. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1385–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixas, F.; Matito, E.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. On the Performance of Some Aromaticity Indices: A Critical Assessment Using a Test Set. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krygowski, T.M.; Szatylowicz, H.; Stasyuk, O.A.; Dominikowska, J.; Palusiak, M. Aromaticity from the Viewpoint of Molecular Geometry: Application to Planar Systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6383–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà, M. Why Aromaticity Is a Suspicious Concept? Why? Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatylowicz, H.; Wieczorkiewicz, P.A.; Krygowski, T.M. Aromaticity Concepts Derived from Experiments. Sci 2022, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máximo-Canadas, M.; Oliveira, R.S.S.; Oliveira, M.A.S.; Borges, I. A New Set of Aromaticity Descriptors Based on the Electron Density Employing the Distributed Multipole Analysis (DMA). ACS Omega 2025, 10, 14157–14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, N.M.P.; Máximo-Canadas, M.; Borges, I. Assessing the Aromaticity of Fluorinated Benzene Derivatives Using New Descriptors Based on the Distributed Multipole Analysis (DMA) Partition of the Electron Density. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2025, 38, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà, M.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Cyrañski, M.K.; Krygowski, T.M.; Merino, G. Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Concepts and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2023; ISBN 9781119085928. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, G.; Solà, M.; Fernández, I.; Foroutan-Nejad, C.; Lazzeretti, P.; Frenking, G.; Anderson, H.L.; Sundholm, D.; Cossío, F.P.; Petrukhina, M.A.; et al. Aromaticity: Quo Vadis. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 5569–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, K.; Tobe, Y. Molecular Loops and Belts. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5274–5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, P.J.; Jasti, R. Molecular Belts. In Polyarenes I; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 249–290. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.-H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, M.-X.; Fraser Stoddart, J. Aromatic Hydrocarbon Belts. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, A.D.; Chandler, G.S. Contracted Gaussian Basis Sets for Molecular Calculations. I. Second Row Atoms, Z. =11–18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, W.J.; Ditchfield, R.; Pople, J.A. Self—Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian—Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian16 Revision C.01 2016, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT, USA. Available online: https://gaussian.com/relnotes/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- dos Santos, L.G.F.; Chagas, J.C.V.; Ferrão, L.F.A.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Nieman, R.; Lischka, H.; Machado, F.B.C. Tuning Aromaticity, Stability and Radicaloid Character of Periacenes by Chemical BN Doping. J. Comput. Chem. 2025, 46, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Perdew, J.P.; Staroverov, V.N.; Scuseria, G.E. Climbing the Density Functional Ladder: Nonempirical Meta–Generalized Gradient Approximation Designed for Molecules and Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 146401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Hansen, A. A Practicable Real-Space Measure and Visualization of Static Electron-Correlation Effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12308–12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, R.; Carvalho, J.R.; Jayee, B.; Hansen, A.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Kertesz, M.; Lischka, H. Polyradical Character Assessment Using Multireference Calculations and Comparison with Density-Functional Derived Fractional Occupation Number Weighted Density Analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 27380–27393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staroverov, V.N.; Scuseria, G.E.; Tao, J.; Perdew, J.P. Comparative Assessment of a New Nonempirical Density Functional: Molecules and Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 11507, Erratum in J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 12129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, J.; Krygowski, T.M. Definition of Aromaticity Basing on the Harmonic Oscillator Model. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 13, 3839–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, J.C. Three Queries about the HOMA Index. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 18699–18710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygowski, T.M. Crystallographic Studies of Inter- and Intramolecular Interactions Reflected in Aromatic Character of. Pi.-Electron Systems. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1993, 33, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Maerker, C.; Dransfeld, A.; Jiao, H.; van Eikema Hommes, N.J.R. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts: A Simple and Efficient Aromaticity Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6317–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wannere, C.S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; von Ragué Schleyer, P. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS) as an Aromaticity Criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultinck, P.; Ponec, R.; Van Damme, S. Multicenter Bond Indices as a New Measure of Aromaticity in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultinck, P.; Rafat, M.; Ponec, R.; Van Gheluwe, B.; Carbó-Dorca, R.; Popelier, P. Electron Delocalization and Aromaticity in Linear Polyacenes: Atoms in Molecules Multicenter Delocalization Index. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7642–7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioslowski, J.; Matito, E.; Solà, M. Properties of Aromaticity Indices Based on the One-Electron Density Matrix. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 6521–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A. AIMAll, Version 19.10.12; TK Gristmill Software: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2019.

- Matito, E. ESI-3D: Electron Sharing Indexes Program for 3D Molecular Space Partitioning, Version 2014; ESI Germany GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Máximo-Canadas, M.; Rosa, N.M.P.; Borges, I., Jr. Aromaticity of Substituted Benzene Derivatives Employing a New Set of Aromaticity Descriptors Based on the Partition of Electron Density. J. Comp. Chem. 2025, 46, e70257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.J.; Alderton, M. Distributed Multipole Analysis. Mol. Phys. 1985, 56, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.J. Distributed Multipole Analysis: Stability for Large Basis Sets. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

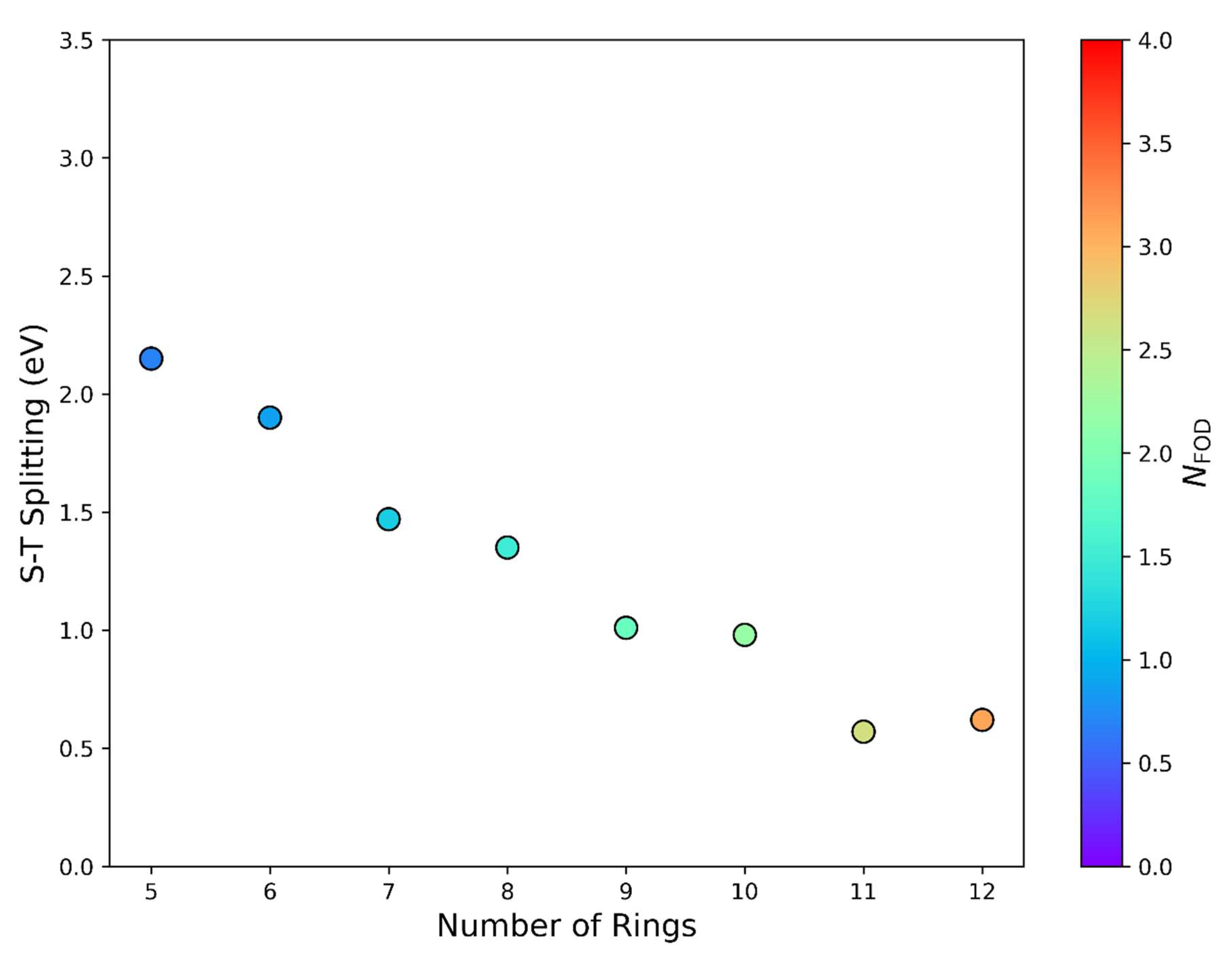

- Pinheiro, M.; Das, A.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Lischka, H.; Machado, F.B.C. Interplay between Aromaticity and Radicaloid Character in Nitrogen-Doped Oligoacenes Revealed by High-Level Multireference Methods. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 9464–9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Plasser, F.; Müller, T.; Libisch, F.; Burgdörfer, J.; Lischka, H. A Comparison of Singlet and Triplet States for One- and Two-Dimensional Graphene Nanoribbons Using Multireference Theory. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2014, 133, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, J.; Pope, M.; Swenberg, C.E.; Alfano, R.R. Heterofission in Pentacene-doped Tetracene Single Crystals. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 1977, 83, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angliker, H.; Rommel, E.; Wirz, J. Electronic Spectra of Hexacene in Solution (Ground State. Triplet State. Dication and Dianion). Chem. Phys. Lett. 1982, 87, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Davidson, E.R.; Yang, W. Nature of Ground and Electronic Excited States of Higher Acenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5098–E5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.R.; Nieman, R.; Kertesz, M.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Hansen, A.; Lischka, H. Multireference Calculations on Bond Dissociation and Biradical Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons as Guidance for Fractional Occupation Number Weighted Density Analysis in DFT Calculations. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2024, 143, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasser, F.; Pašalić, H.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Libisch, F.; Reiter, R.; Burgdörfer, J.; Müller, T.; Shepard, R.; Lischka, H. The Multiradical Character of One- and Two-Dimensional Graphene Nanoribbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2581–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

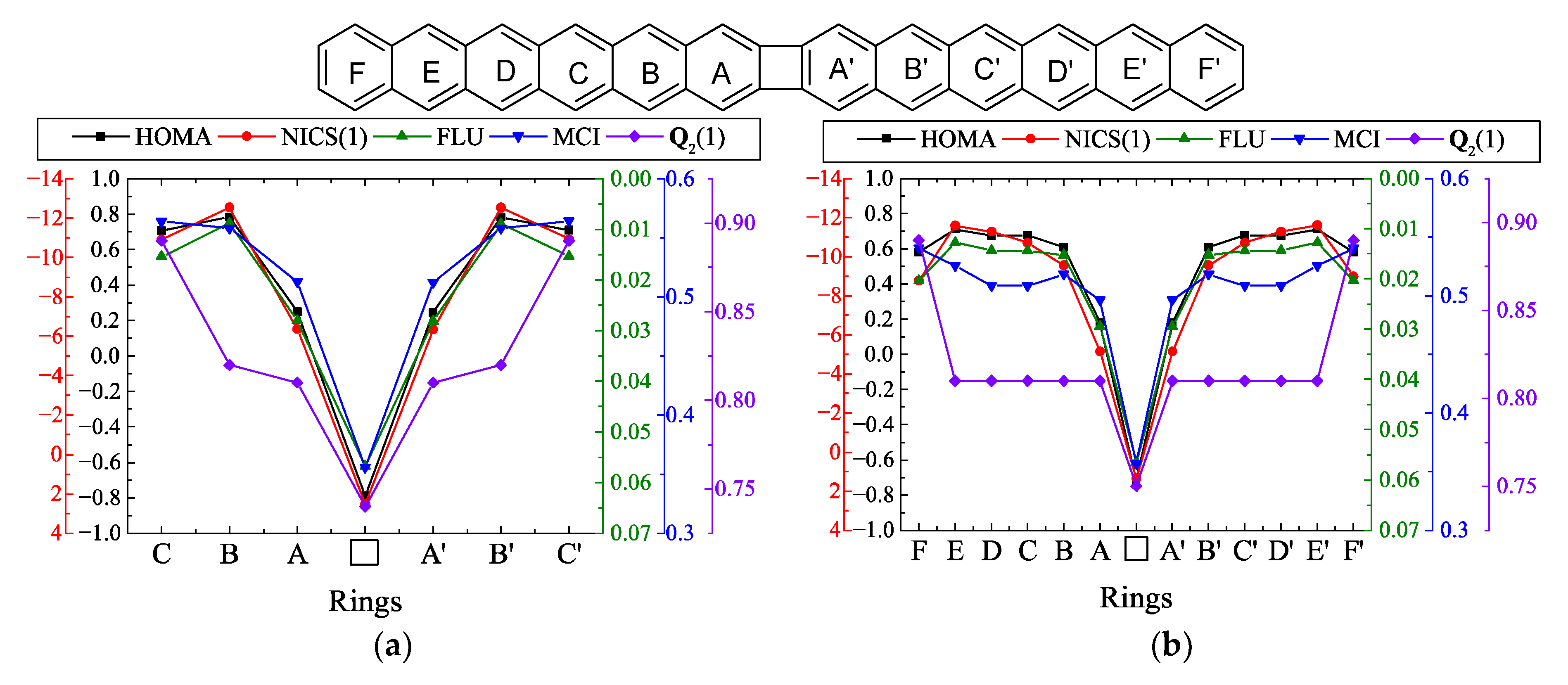

- Kalam, H.; Kerim, A.; Najmidin, K.; Abdurishit, P.; Tawar, T. A Study on the Aromaticity of [n]Phenacenes and [n]Helicenes (N = 3–9). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 592, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portella, G.; Poater, J.; Bofill, J.M.; Alemany, P.; Solà, M. Local Aromaticity of [n]Acenes, [n]Phenacenes, and [n]Helicenes (n = 1–9). J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2509–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Photochemical Synthesis and Electronic Spectra of Fulminene ([6]Phenacene). Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Baltazar, J.; Tovar, J.D. Manifestations of Antiaromaticity in Organic Materials: Case Studies of Cyclobutadiene, Borole, and Pentalene. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanez, B.D.; Chagas, J.C.V.; Pinheiro, M., Jr.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Lischka, H.; Machado, F.B.C. Effects on the Aromaticity and on the Biradicaloid Nature of Acenes by the Inclusion of a Cyclobutadiene Linkage. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2020, 139, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, I.; Stoica, O.; Krawiec, M.; Blieck, R.; Zuzak, R.; Stępień, M.; Echavarren, A.M.; Godlewski, S. On-Surface Synthesis of a Phenylene Analogue of Nonacene. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 4063–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; Janeiro, J.; Cobas, A.; Ortuño, M.A.; Peña, D.; Guitián, E.; Pérez, D. Aryne-Based Synthesis of Cyclobutadiene-Containing Oligoacenes and Related Extended Biphenylene Derivatives. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, D.; Schmidt, W. Diels-Alder Reactivity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. 1. Acenes and Benzologs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 3163–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijegorodov, N.; Ramachandran, V.; Winkoun, D.P. The Dependence of the Absorption and Fluorescence Parameters, the Intersystem Crossing and Internal Conversion Rate Constants on the Number of Rings in Polyacene Molecules. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1997, 53, 1813–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

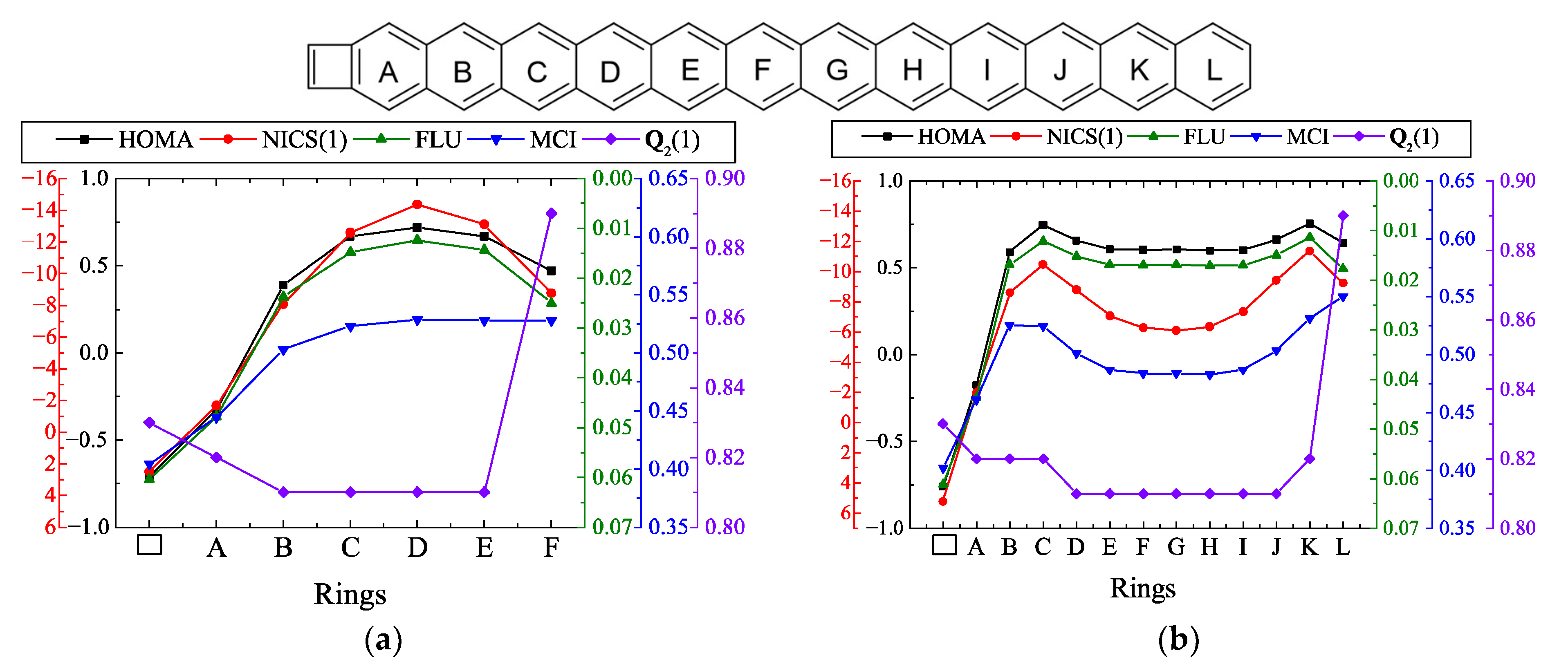

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, K.S. Structures, Magnetic Properties, and Aromaticity of Cyclacenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2256–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, H.-L.; Su, Z.-M. NICS Values Scan in Three-Dimensional Space of the Hoop-Shaped π-Conjugated Molecules [6]8 Cyclacene and [16]Trannulene. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, D.; Lu, X.; Bettinger, H.F.; Dai, S.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Houk, K.N. Open-Shell Singlet Character of Cyclacenes and Short Zigzag Nanotubes. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5449–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Faginas-Lago, N.; Andrae, D.; Evangelisti, S.; Leininger, T. Increasing Radical Character of Large [n]Cyclacenes Unveiled by Wave Function Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 3746–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.-H.; Wang, M.-X. Zigzag Hydrocarbon Belts. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowsky, D.; McNeill, K.; Cramer, C.J. Electronic Structures of [n]-Cyclacenes (n = 6–12) and Short, Hydrogen-Capped, Carbon Nanotubes. Faraday Discuss. 2010, 145, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögtle, F. (Ed.) Cyclophanes II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; Volume 115, ISBN 978-3-540-12478-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.-H.; Guo, Q.-H.; Tong, S.; Wang, M.-X. Zigzag-Type Molecular Belts: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 2573–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Heine, M.W.D. Dewar Benzenoids in Cyclophenacene Nanobelts. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 797, 139576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Heine, M.W.D. Vibrational Stabilization in Cyclacene Carbon Nanobelts. J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 8601–8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, A. Nucleus Independent Chemical Shift (NICS) at Small Distances from the Molecular Plane: The Effect of Electron Density. Chemphyschem 2023, 24, e202300080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambiagi, M.; de Giambiagi, M.S.; Silva, C.D.d.S.; de Figueiredo, A.P. Multicenter bond indices as a measure of aromaticity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000, 2, 3381–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.A.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. The Fractional Occupation Number Weighted Density as a Versatile Analysis Tool for Molecules with a Complicated Electronic Structure. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6150–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

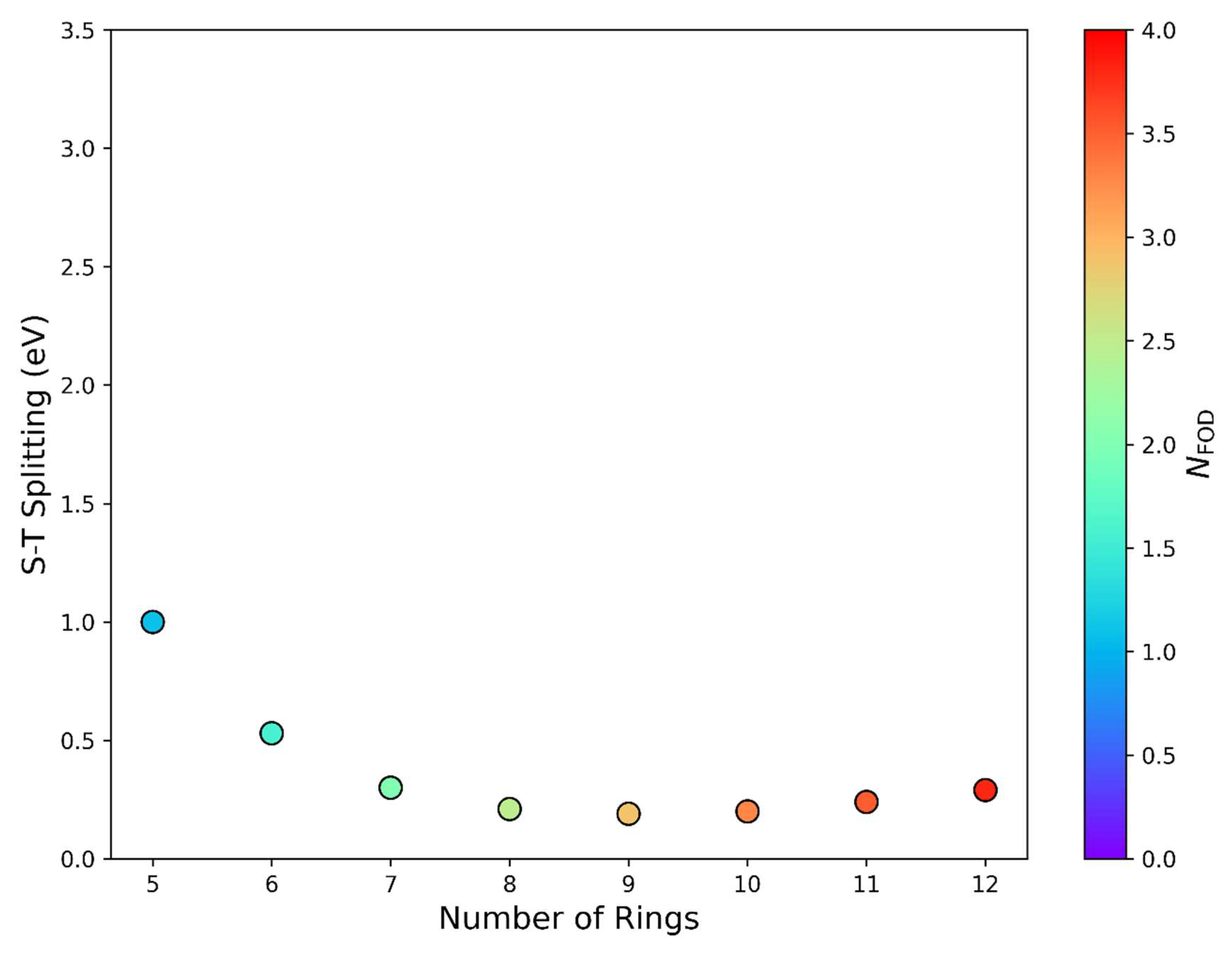

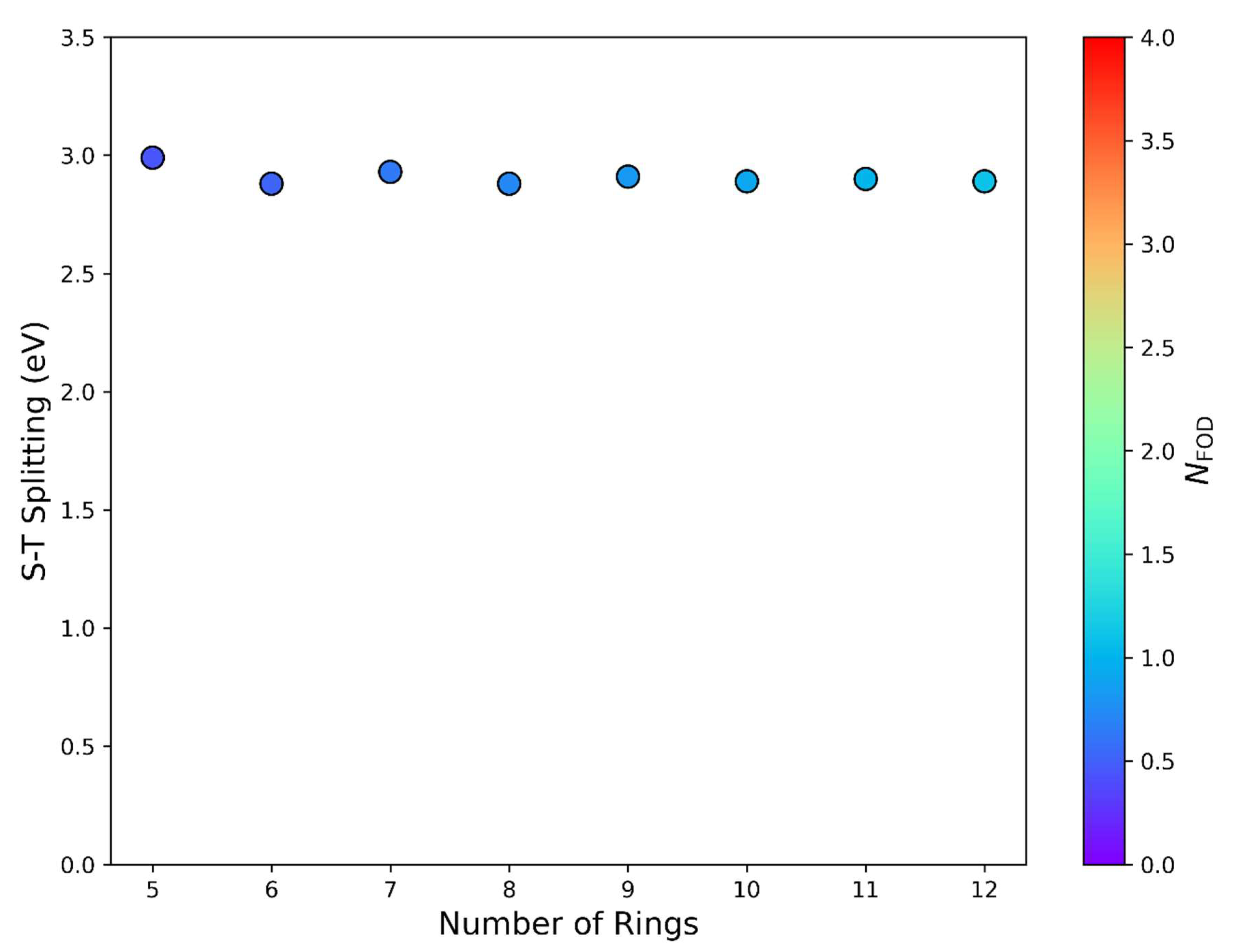

| |||||

| n | HOMA a | NICS b | FLU a | MCI a | b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.323 | −13.35 | 0.0217 | 0.0098 | 0.321 |

| 6 | 0.608 | −19.11 | 0.0168 | 0.0131 | 0.373 |

| 7 | 0.598 | 3.01 | 0.0170 | 0.0127 | 0.290 |

| 8 | 0.613 | −15.17 | 0.0168 | 0.0131 | 0.185 |

| 9 | 0.628 | 0.05 | 0.0164 | 0.0134 | 0.100 |

| 10 | 0.618 | −9.04 | 0.0166 | 0.0133 | 0.052 |

| 11 | 0.631 | −2.66 | 0.0163 | 0.0136 | 0.028 |

| 12 | 0.624 | −4.84 | 0.0164 | 0.0135 | 0.016 |

| |||||

| n | HOMA a | NICS b | FLU a | MCI a | b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.325 | −0.46 | 0.0238 | 0.0200 | 0.012 |

| 8 | 0.553 | −6.26 | 0.0191 | 0.0230 | 0.027 |

| 10 | 0.62 | −7.14 | 0.0173 | 0.0239 | 0.035 |

| 12 | 0.648 | −6.57 | 0.0164 | 0.0245 | 0.025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salles, G.A.; Magalhães, P.R.C.; Carvalho, J.R.; Máximo-Canadas, M.; Rosa, N.M.P.; Chagas, J.C.V.; Ferrão, L.F.A.; Aquino, A.J.A.; Borges, I., Jr.; Machado, F.B.C.; et al. Aromaticity Study of Linear and Belt-like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chemistry 2025, 7, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060178

Salles GA, Magalhães PRC, Carvalho JR, Máximo-Canadas M, Rosa NMP, Chagas JCV, Ferrão LFA, Aquino AJA, Borges I Jr., Machado FBC, et al. Aromaticity Study of Linear and Belt-like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060178

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalles, Guilherme A., Paulo R. C. Magalhães, Jhonatas R. Carvalho, Matheus Máximo-Canadas, Nathália M. P. Rosa, Julio C. V. Chagas, Luiz F. A. Ferrão, Adelia J. A. Aquino, Itamar Borges, Jr., Francisco B. C. Machado, and et al. 2025. "Aromaticity Study of Linear and Belt-like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060178

APA StyleSalles, G. A., Magalhães, P. R. C., Carvalho, J. R., Máximo-Canadas, M., Rosa, N. M. P., Chagas, J. C. V., Ferrão, L. F. A., Aquino, A. J. A., Borges, I., Jr., Machado, F. B. C., & Lischka, H. (2025). Aromaticity Study of Linear and Belt-like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chemistry, 7(6), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060178