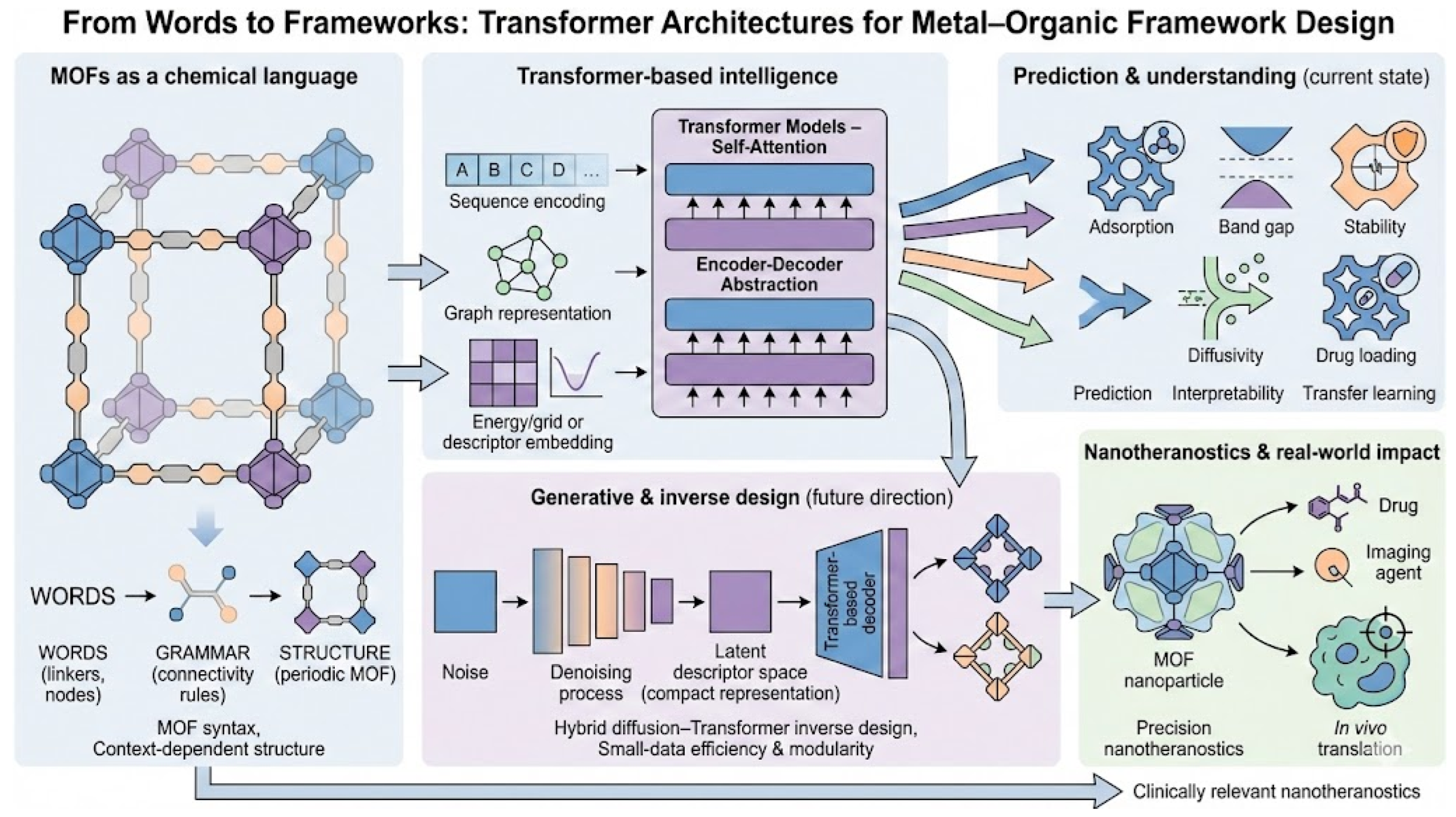

From Words to Frameworks: Transformer Models for Metal–Organic Framework Design in Nanotheranostics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transformer Architecture

2.1. Encoder

2.2. Decoder

2.3. Variations in the Transformer Architecture

2.4. Attention Mechanism in Transformers

2.5. Advantages of Transformers over Traditional Models

3. Why Do MOFs Benefit from Transformer Architectures?

3.1. Capturing Higher-Order Context: Metal Center + Organic Linker + Synthesis Conditions

3.2. Functional Group Introduction as a Design Switch: From Structural Equivalence to Functional Divergence

3.3. Representing MOFs for Transformer Models

4. Addressing Data Limitations in MOF Prediction Models: Strategies and Advances

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | CoRE MOF | MOFX-DB | CoRE COF | CSD | QMOF-DB | DigiMOF | ARC-MOF | Boyd&Woo | |

| Source | [240] | [241] | [242] | [243] | [82,229] | [229] | [228] | [244] | |

| Data volume | 25,000+ MOFs | 168,000+ MOFs | 187 COFs | 88,000+ MOFs | 20,000+ MOFs | 52,000 | 280,000+ MOFs | 324,426 MOFs | |

| Information | 3D Structures | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Physical Properties | x | x | - | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Chemical Properties | x | x | - | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Synthetic Data | x | - | x | x | - | - | - | - | |

| Hypothetical MOFs | x | x | - | - | x | x | x | x | |

| Physical Interactions | x | x | - | - | x | - | x | - | |

| Code available | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | |

| Other Properties | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Access Type | Open | Open | Open | Restricted | Open | Open | Open | Open | |

| Date last version | 2024 | 2022 | 2024 | 2024 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2019 | |

| Type | Real and generated data | Real and generated data | Experimental data | Experimental data | Real and generated data | Generated data | Real and generated data | Real and generated data | |

| Downloads | 31K | - | - | - | - | - | 9K | - | |

5. Recent Breakthroughs in Transformer-Based Approaches

5.1. MOFNet—Graph Transformer for Isotherms

5.2. MOFormer: Self-Supervised Transformer Model

5.3. MOFTransformer—Multi-Modal Transformer

5.4. Uni-MOF Universal Gas Predictor

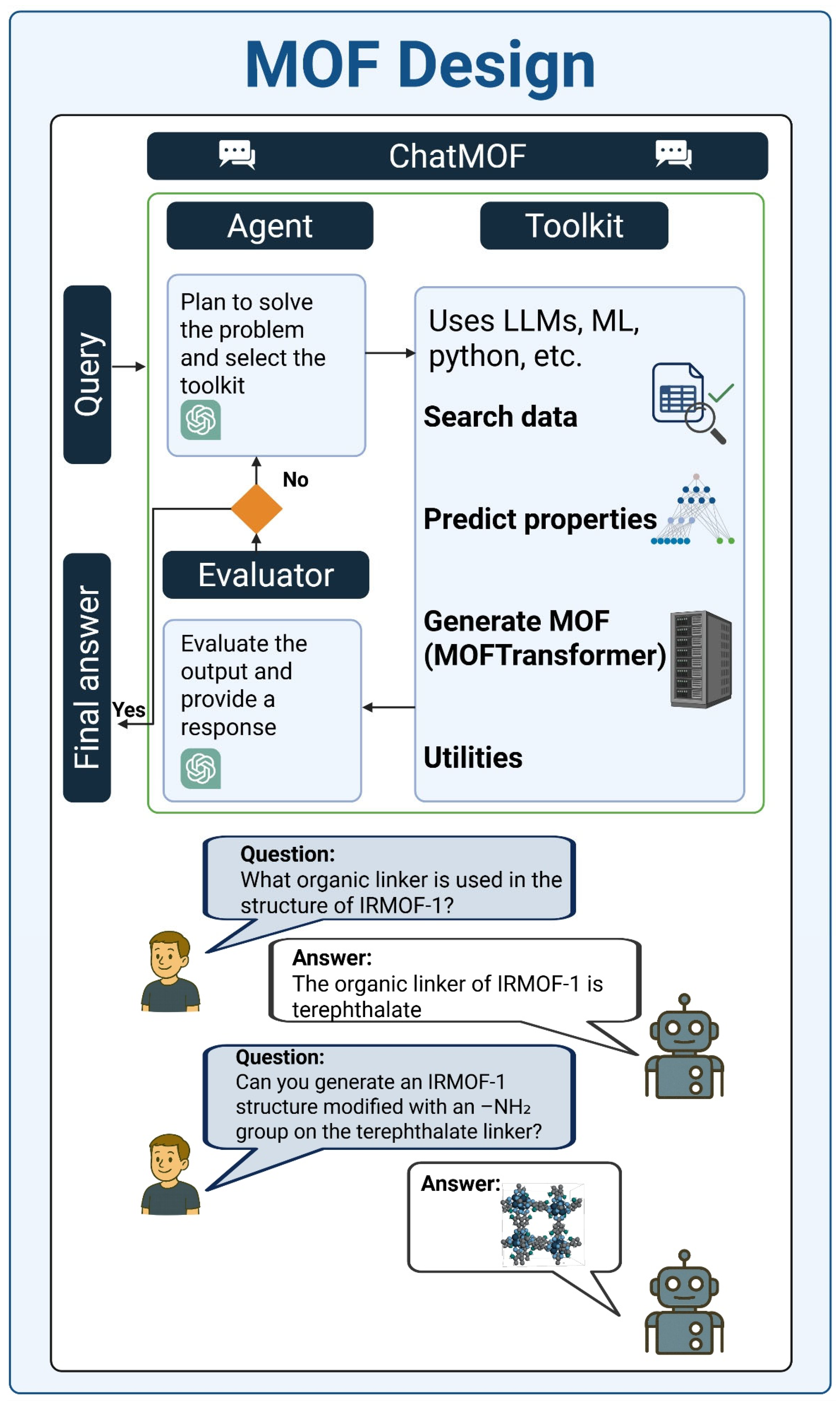

5.5. Agents for MOF Design

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mondal, I.; Haick, H. Smart Dust for Chemical Mapping. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2419052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.M.; Ku, C.-E.; Zhang, C. Hyperselective Carbon Membranes for Precise High-Temperature H2 and CO2 Separation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppe, J.; Yakimov, A.V.; Gioffrè, D.; Usteri, M.-E.; Vosegaard, T.; Pintacuda, G.; Lesage, A.; Pell, A.J.; Mitchell, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; et al. Coordination Environments of Pt Single-Atom Catalysts from NMR Signatures. Nature 2025, 642, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Bao, M.; Meng, F.; Ma, B.; Feng, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhong, R.; Xi, S.; et al. Designer Topological-Single-Atom Catalysts with Site-Specific Selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Shen, J. A Review: Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles for Environmental Applications. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 15068–15085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, C.F.; Quezada, V.; Guzmán-Sastoque, P.; Orozco, J.C.; Reyes, L.H.; Osma, J.F.; Muñoz-Camargo, C.; Cruz, J.C. A Mathematical Phase Field Model Predicts Superparamagnetic Nanoparticle Accelerated Fusion of HeLa Spheroids for Field Guided Biofabrication. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.F.; Guzmán-Sastoque, P.; Santacruz-Belalcazar, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Villamarin, P.; Reyes, L.H.; Cruz, J.C. Magnetoliposomes for Nanomedicine: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications in Drug, Gene, and Peptide Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2025, 22, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yan, S.; Yan, X.; Lv, Y. Recent Advances in Metal-Organic Frameworks: Synthesis, Application and Toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yadav, A.; Zhou, H.; Roy, K.; Thanasekaran, P.; Lee, C. Advances and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Emerging Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, L.; Omoding, D.; Jayswal, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Advances and Prospects in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Using MOFs and COFs: Mechanism and AI-Assisted Strategies. React. Funct. Polym. 2026, 219, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Han, Z.; Fan, J. Review of Synthesis and Separation Application of Metal-Organic Framework-Based Mixed-Matrix Membranes. Polymers 2023, 15, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal–Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-B.; Liang, J.; Wang, X.-S.; Cao, R. Multifunctional Metal–Organic Framework Catalysts: Synergistic Catalysis and Tandem Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 126–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptopoulou, C.P. Metal-Organic Frameworks: Synthetic Methods and Potential Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Hanikel, N.; Lomachenko, K.A.; Atzori, C.; Lund, A.; Lyu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Angell, C.A.; Yaghi, O.M. High-Porosity Metal-Organic Framework Glasses. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202300003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeim, H.; Molahalli, V.; Prajongthat, P.; Pattanaporkratana, A.; Pathak, G.; Phettong, B.; Hongkarnjanakul, N.; Chattham, N. Porosity Tunable Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Composites for Energy Storage Applications: Recent Progress. Polymers 2025, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, X.; Kang, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, D. Isoreticular Chemistry within Metal–Organic Frameworks for Gas Storage and Separation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 213968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, F. Progress and Potential of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Gas Storage and Separation: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.-L. Microenvironment Modulation in Metal–Organic Framework-Based Catalysis. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021, 2, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Pan, T.; Wang, L.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, W.; Huo, F. Programmable Logic in Metal–Organic Frameworks for Catalysis. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, H.; Ghasemzadeh, S.; Ghoreishi, Z.; Majidi, M.R.; Yoon, Y.; Dizge, N.; Khataee, A. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOF)-Based Sensors for Detection of Toxic Gases: A Review of Current Status and Future Prospects. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 299, 127512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Yang, W. Applications of Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Sensors for Food Safety: Enhancing Mechanisms and Recent Advances. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ge, S.; Liew, R.K.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Tran, T. Van Recent Progress and Challenges of MOF-Based Nanocomposites in Bioimaging, Biosensing and Biocarriers for Drug Delivery. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1800–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.D.; Walton, S.P.; Chan, C. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Drug Delivery: A Design Perspective. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7004–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khafaga, D.S.R.; El-Morsy, M.T.; Faried, H.; Diab, A.H.; Shehab, S.; Saleh, A.M.; Ali, G.A.M. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Drug Delivery: Engineering Versatile Platforms for Therapeutic Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 30201–30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khulood, M.T.; Jijith, U.S.; Naseef, P.P.; Kallungal, S.M.; Geetha, V.S.; Pramod, K. Advances in Metal-Organic Framework-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 673, 125380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Liang, T.; Zheng, J.; Chen, G.; Ye, Y.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A.; Lu, L.; Song, Z.; Huang, Y. MOF-Based Platforms on Diabetic Disease: Advanced and Prospect of Effective Diagnosing and Therapy. React. Funct. Polym. 2026, 218, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, M.J.; Zubillaga, M. Theranostic Nanoplatforms in Nuclear Medicine: Current Advances, Emerging Trends, and Perspectives for Personalized Oncology. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; Bayoumi, L.; Helal, N.F.; Mohamed, N.R.A.; Emarh, Y.; Ahmed, A.M. Emerging Trends in NanoTheranostics: Integrating Imaging and Therapy for Precision Health Care. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinbasak, I.; Alp, Y.; Sanyal, R.; Sanyal, A. Theranostic Nanogels: Multifunctional Agents for Simultaneous Therapeutic Delivery and Diagnostic Imaging. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 14033–14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Sastoque, P.; Rodríguez, C.F.; Monsalve, M.C.; Castellanos, S.; Manrique-Moreno, A.; Reyes, L.H.; Cruz, J.C. Nanotheranostics Revolutionizing Gene Therapy: Emerging Applications in Gene Delivery Enhancement. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Cong, C. Insights and Advances of Theranostic Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Liu, M.; Yu, Q.; Ge, D.; Zhang, J. Metal–Organic Framework Nanomaterials as a Medicine for Catalytic Tumor Therapy: Recent Advances. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehata, A.K.; Vikas; Viswanadh, M.K.; Muthu, M.S. Theranostics of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Image-Guided Nanomedicine for Clinical Translation. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X. Metal-Organic Frameworks-Loaded Indocyanine Green for Enhanced Phototherapy: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1601476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantwalawalkar, J.; Mhettar, P.; Nangare, S.; Mali, R.; Ghule, A.; Patil, P.; Mohite, S.; More, H.; Jadhav, N. Stimuli-Responsive Design of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Cancer Theranostics: Current Challenges and Future Perspective. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4497–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Chi, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z. AI-Driven Advances in Metal–Organic Frameworks: From Data to Design and Applications. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 15972–16001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, S.; Magar, R.; Antony, A.; Meda, R.S.; Barati Farimani, A. MOFGPT: Generative Design of Metal–Organic Frameworks Using Language Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 9049–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, S.; Qian, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, M.; Zheng, B.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J. Advances and Challenges of ZIF-Based Nanocomposites in Immunotherapy and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2026, 14, 841–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, R. The Historical Development of the Concepts Underlying the Design and Construction of Targeted Coordination Polymers/MOFs: A Personal Account. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202400038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yifu, C. Metal-Organic Frameworks: Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Prospects. In Metal Organic Frameworks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.F.; Sabouni, R.; Garg, R.; Gomaa, H. Recent Advances in Metal-Organic Frameworks as Nanocarriers for Triggered Release of Anticancer Drugs: Brief History, Biomedical Applications, Challenges and Future Perspective. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 225, 113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, G.; Li, H. Selective Binding and Removal of Guests in a Microporous Metal–Organic Framework. Nature 1995, 378, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, H. Hydrothermal Synthesis of a Metal-Organic Framework Containing Large Rectangular Channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10401–10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghade, D.; Shelare, S.; Prakash, C.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Yunus Khan, T.M.; Kalam, M.A. Innovations in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Pioneering Adsorption Approaches for Persistent Organic Pollutant (POP) Removal. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Datta, S.J.; Zhou, S.; Jia, J.; Shekhah, O.; Eddaoudi, M. Advances in Metal–Organic Framework-Based Membranes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8300–8350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recent Progress in Strategies for Preparation of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Hybrids with Different Dimensions. Chem. Synth. 2022, 3, 1. [CrossRef]

- Rangnekar, N.; Mittal, N.; Elyassi, B.; Caro, J.; Tsapatsis, M. Zeolite Membranes—A Review and Comparison with MOFs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7128–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teffu, D.M.; Makgopa, K.; Somo, T.R.; Ratsoma, M.S.; Honey, S.; Makhado, E.; Modibane, K.D. Metal and Covalent Organic Frameworks (MOFs and COFs): A Comprehensive Overview of Their Synthesis, Characterization and Enhanced Supercapacitor Performance. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 540, 216798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Taheri-Ledari, R.; Saeidirad, M.; Qazi, F.S.; Kashtiaray, A.; Ganjali, F.; Tian, Y.; Maleki, A. Regulation of Porosity in MOFs: A Review on Tunable Scaffolds and Related Effects and Advances in Different Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Xin, R.; Earnshaw, J.; Tang, J.; Hill, J.P.; Ashok, A.; Nanjundan, A.K.; Kim, J.; Young, C.; Sugahara, Y.; et al. MOF-Derived Nanoporous Carbons with Diverse Tunable Nanoarchitectures. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2990–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Han, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. The Key to MOF Membrane Fabrication and Application: The Trade-off between Crystallization and Film Formation. Chem.—Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202401868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorlu, T.; Hetey, D.; Reithofer, M.R.; Chin, J.M. Physicochemical Methods for the Structuring and Assembly of MOF Crystals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Bai, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Jun, S.C.; Yamauchi, Y.; Chen, L. Emerging Pristine MOF-Based Heterostructured Nanoarchitectures: Advances in Structure Evolution, Controlled Synthesis, and Future Perspectives. Small 2023, 19, 2303884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Samsami, S.; Ghaffarkhah, A.; Hashemi, S.A.; Ghasemi, S.; Amini, M.; Wuttke, S.; Rojas, O.; Tam, K.C.; Jiang, F.; et al. MOF-Based Electromagnetic Shields Multiscale Design: Nanoscale Chemistry, Microscale Assembly, and Macroscale Manufacturing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2304473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirlikovali, K.O.; Hanna, S.L.; Son, F.A.; Farha, O.K. Back to the Basics: Developing Advanced Metal–Organic Frameworks Using Fundamental Chemistry Concepts. ACS Nanosci. Au 2023, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Gates, B.C. Analyzing Stabilities of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Correlation of Stability with Node Coordination to Linkers and Degree of Node Metal Hydrolysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 8551–8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, T.; Zhou, T.; Shang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Shang, C.; Guo, Z. Porosity Engineering of MOF-Based Materials for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbina, V.V.; Belik, Y.A.; Vodyankina, O.V. Effect of Organic Linker Substituents on Properties of Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Review. React. Chem. Eng. 2025, 10, 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.C.; Huang, L. Advances in Metal–Organic Frameworks for the Removal of Chemical Warfare Agents: Insights into Hydrolysis and Oxidation Reaction Mechanisms. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewska, P.; Haponiuk, J.; Saeb, M.R.; Rabiee, N.; Bencherif, S.A. Mitigating Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) Toxicity for Biomedical Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ayyoubzadeh, S.M.; Ghorbani-Bidkorbeh, F.; Shahhosseini, S.; Dadashzadeh, S.; Asadian, E.; Mosayebnia, M.; Siavashy, S. An Investigation of Affecting Factors on MOF Characteristics for Biomedical Applications: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavykina, A.; Kolobov, N.; Khan, I.S.; Bau, J.A.; Ramirez, A.; Gascon, J. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Heterogeneous Catalysis: Recent Progress, New Trends, and Future Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8468–8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Guo, J.; Tang, Z. Engineering Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks for Heterogeneous Catalysis. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lv, X.; Jin, L.; Du, K.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, X.; Liang, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Facile Synthesis of Sn-Doped MOF-5 Catalysts for Efficient Photocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 344, 123586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.-J.; Yang, C.; Tang, Z. Enabling Long-Distance Hydrogen Spillover in Nonreducible Metal-Organic Frameworks for Catalytic Reaction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Song, H.; Huang, Z.; Su, Y.; Lv, Y. Multisignals Sensing Platform for Highly Sensitive, Accurate, and Rapid Detection of p -Aminophenol Based on Adsorption and Oxidation Effects Induced by Defective NH2-Ag-NMOFs. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 3137–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, J.; Peng, Y.; Cao, S.; Zhang, S.; Pang, H. Applications of Metal Nanoparticles/Metal-Organic Frameworks Composites in Sensing Field. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, L.; Yang, P.; Hou, X. Nanoscale Metal Organic Frameworks and Their Applications in Disease Diagnosis and Therapy. Microchem. J. 2022, 180, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Z.-H.; Xu, H. Nanoscale Metal−Organic Frameworks and Their Nanomedicine Applications. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 834171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S.; Sun, Y. A Short Review of Advances in MOF Glass Membranes for Gas Adsorption and Separation. Membranes 2024, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.; Aulakh, D.; Purewal, J.; Siegel, D.J.; Veenstra, M.; Matzger, A.J. Optimizing Hydrogen Storage in MOFs through Engineering of Crystal Morphology and Control of Crystal Size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10727–10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y. A Long-Lasting TIF-4 MOF Glass Membrane for Selective CO2 Separation. J. Memb. Sci. 2022, 655, 120611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yan, W.; Kang, Z.; Zou, X.; Fan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, R.; Sun, D. Thermal Treatment Optimization of Porous MOF Glass and Polymer for Improving Gas Permeability and Selectivity of Mixed Matrix Membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ren, Y.; Cheng, H.; Jiao, Y.; Shi, S.; Gao, L.; Xie, H.; Gao, J.; Sun, L.; Hou, J. Metal-Organic Framework Glass Catalysts from Melting Glass-Forming Cobalt-Based Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework for Boosting Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Y.; Kou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lu, P. Metal Organic Framework Glasses: A New Platform for Electrocatalysis? Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, N.; Azad, M.; Mehrabi, Z.; Dini, G.; Marandi, A. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications: Bridging Materials Science and Regenerative Medicine. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 34481–34509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Tang, H.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Ren, Z.; Wu, S.; Xia, D.; Zheng, Y. Bridging Biodegradable Metals and Biodegradable Polymers: A Comprehensive Review of Biodegradable Metal–Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Application. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2026, 155, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidanemariam, A.; Cho, S. Recent Advancements in Metal–Organic Framework-Based Microfluidic Chips for Biomedical Applications. Micromachines 2025, 16, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H.; Daglar, H.; Gulbalkan, H.C.; Aksu, G.O.; Keskin, S. Recent Advances in Computational Modeling of MOFs: From Molecular Simulations to Machine Learning. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 484, 215112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.L.; Fahy, K.M.; Morris, W.; Dravid, V.P.; Hernandez, B.; Farha, O.K. The Road Ahead for Metal–Organic Frameworks: Current Landscape, Challenges and Future Prospects. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.S.; Fung, V.; Huck, P.; O’Donnell, C.T.; Horton, M.K.; Truhlar, D.G.; Persson, K.A.; Notestein, J.M.; Snurr, R.Q. High-Throughput Predictions of Metal–Organic Framework Electronic Properties: Theoretical Challenges, Graph Neural Networks, and Data Exploration. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, B.; Yurdusen, A.; Stock, N.; Maurin, G.; Serre, C. Synthetic Aspects and Characterization Needs in MOF Chemistry—From Discovery to Applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2411359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Du, D. Bayesian Optimization Enhanced Neural Networks for Predicting Metal-Organic Framework Morphology: A ZIF-8 Synthesis Case Study. Mater. Lett. 2025, 380, 137738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kang, Y.; Choe, W.; Kim, J. Mining Insights on Metal–Organic Framework Synthesis from Scientific Literature Texts. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Yan, W.; Dong, L.; Deng, S.; Wilkinson, D.P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Catalytically Active Sites of MOF-Derived Electrocatalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, Theoretical Calculations, and Functional Mechanisms. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2021, 9, 20320–20344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharissova, O.V.; Kharisov, B.I.; González, L.T. Recent Trends on Density Functional Theory–Assisted Calculations of Structures and Properties of Metal–Organic Frameworks and Metal–Organic Frameworks-Derived Nanocarbons. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 1424–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Wang, Q.; Peng, C.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Tsidaeva, N.; Wang, W. MOF-Derived CoS2/WS2 Electrocatalysts with Sulfurized Interface for High-Efficiency Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: Synthesis, Characterization and DFT Calculations. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, T.; Fazly Abdul Patah, M.; Hoong Wong, Y.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Probing the Capability of the MOF-74(Ni)@GrO Composite for CO2 Adsorption and CO2/N2 Separation: A Combination of Experimental and Molecular Dynamic Simulation Studies. Fuel 2024, 372, 131837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman.FM, F.; Taha, M.; Farghali, A.A.; Abdelhameed, R.M. Synthesis and Applications of Porphyrin-Based MOFs in Removal of Pesticide from Wastewater: Molecular Simulations and Experimental Studies. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 6697–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroushaki, T.; Dekamin, M.G.; Hashemianzadeh, S.M.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Ganjali Koli, M. A Molecular Dynamic Simulation Study of Anticancer Agents and UiO-66 as a Carrier in Drug Delivery Systems. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2022, 113, 108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.-J.; Wang, D.-R.; Lu, W.; Li, D. Machine Learning-Assisted Discovery of Propane-Selective Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 6955–6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Yan, X.; Zhu, R.; Huerta, E.A.; Chaudhuri, S.; Cooper, D.; Foster, I.; Tajkhorshid, E. A Generative Artificial Intelligence Framework Based on a Molecular Diffusion Model for the Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Carbon Capture. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Tomiya, S.; Lin, J. An Interpretable and Transferrable Vision Transformer Model for Rapid Materials Spectra Classification. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Artificial Intelligence Meets Laboratory Automation in Discovery and Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 4637–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K. AtomGPT: Atomistic Generative Pretrained Transformer for Forward and Inverse Materials Design. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 6909–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.; Rittig, J.G.; Wolf, A.B.; Grohe, M.; Burger, J.; Mitsos, A.; Grimm, D.G. GraphXForm: Graph Transformer for Computer-Aided Molecular Design. Digit. Discov. 2025, 4, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M.; Ke, G.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, Z.; Lu, D. A Comprehensive Transformer-Based Approach for High-Accuracy Gas Adsorption Predictions in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xu, J.; Niu, Z.; Zhan, S.; Ma, W. LLM-Mambaformer: Integrating Mamba and Transformer for Crystalline Solids Properties Prediction. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Du, Z.; Shu, L.; Cen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, H. Transformer-Generated Atomic Embeddings to Enhance Prediction Accuracy of Crystal Properties with Machine Learning. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Park, H.; Smit, B.; Kim, J. A Multi-Modal Pre-Training Transformer for Universal Transfer Learning in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Lee, W.; Bae, T.; Han, S.; Jang, H.; Kim, J. Harnessing Large Language Models to Collect and Analyze Metal–Organic Framework Property Data Set. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 3943–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Magar, R.; Wang, Y.; Barati Farimani, A. MOFormer: Self-Supervised Transformer Model for Metal–Organic Framework Property Prediction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2958–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wu, H. Comprehensive Overview of Machine Learning Applications in MOFs: From Modeling Processes to Latest Applications and Design Classifications. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2025, 13, 2403–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.; Kang, Y.; Lim, Y.; Kim, J. From Data to Discovery: Recent Trends of Machine Learning in Metal–Organic Frameworks. JACS Au 2024, 4, 3727–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neikha, K.; Puzari, A. Metal–Organic Frameworks through the Lens of Artificial Intelligence: A Comprehensive Review. Langmuir 2024, 40, 21957–21975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen, P.; Trojovský, P. Overview and Challenges of Machine Translation for Contextually Appropriate Translations. iScience 2024, 27, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ruan, Q.; Qian, S.; Zhang, M. A Hybrid Model Based on Transformer and Mamba for Enhanced Sequence Modeling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, L.; Ke, L.; Dou, B.; Zhang, C.; Feng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, B.; Wei, G. A Review of Transformers in Drug Discovery and Beyond. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 15, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. A Survey of Transformers. AI Open 2022, 3, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggrainingsih, R.; Hassan, G.M.; Datta, A. Transformer-Based Models for Combating Rumours on Microblogging Platforms: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakehal, A.; Alti, A.; Annane, B. CORES: Context-Aware Emotion-Driven Recommendation System-Based LLM to Improve Virtual Shopping Experiences. Future Internet 2025, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.Y.; Cheok, A.D.; Pan, Z.; Cai, J.; Yan, Y. From Turing to Transformers: A Comprehensive Review and Tutorial on the Evolution and Applications of Generative Transformer Models. Sci 2023, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, T.; Luo, H. Rethinking Position Embedding Methods in the Transformer Architecture. Neural Process. Lett. 2024, 56, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choo, H.; Jeong, J. Self-Attention (SA)-ConvLSTM Encoder–Decoder Structure-Based Video Prediction for Dynamic Motion Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Vogt, M.; Bajorath, J. DeepAC—Conditional Transformer-Based Chemical Language Model for the Prediction of Activity Cliffs Formed by Bioactive Compounds. Digit. Discov. 2022, 1, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdal Hafeth, D.; Kollias, S. Insights into Object Semantics: Leveraging Transformer Networks for Advanced Image Captioning. Sensors 2024, 24, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Duan, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, F.; Tang, H.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. TransGEM: A Molecule Generation Model Based on Transformer with Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanksale, V. Transformers for Network Traffic Prediction. In 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 236–240.

- Sajun, A.R.; Zualkernan, I.; Sankalpa, D. A Historical Survey of Advances in Transformer Architectures. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, G.; Schulze Balhorn, L.; Schweidtmann, A.M. Learning from Flowsheets: A Generative Transformer Model for Autocompletion of Flowsheets. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 171, 108162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Dong, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Bao, Z. RB-GAT: A Text Classification Model Based on RoBERTa-BiGRU with Graph ATtention Network. Sensors 2024, 24, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tato, F.R.; Ibrahim, I.M. State-Of-The-Art Named Entity Recognition and Related Extraction: A Review. Eng. Technol. J. 2025, 10, 4315–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Cambria, E.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Gao, J. Deep Learning-Based Text Classification. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Sun, T.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Dai, N.; Huang, X. Pre-Trained Models for Natural Language Processing: A Survey. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2020, 63, 1872–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Sirrianni, J.; Linwood, S.L. Operationalizing and Implementing Pretrained, Large Artificial Intelligence Linguistic Models in the US Health Care System: Outlook of Generative Pretrained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) as a Service Model. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e32875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Chiriatti, M. GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. ChatGPT: A Comprehensive Review on Background, Applications, Key Challenges, Bias, Ethics, Limitations and Future Scope. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Solanki, A. Improving ROUGE-1 by 6%: A Novel Multilingual Transformer for Abstractive News Summarization. Concurr. Comput. 2024, 36, e8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayyanu, Z.M. Revolutionising Translation Technology: A Comparative Study of Variant Transformer Models—BERT, GPT, and T5. Comput. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2024, 14, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, P.; Verraest, A.E.C.; Eleftheroglou, N.; Zarouchas, D. Intelligent Fatigue Damage Tracking and Prognostics of Composite Structures Utilizing Raw Images via Interpretable Deep Learning. Compos. B Eng. 2024, 287, 111863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ke, L.; Chen, L.; Dou, B.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, T.; Wei, G. Transformer Technology in Molecular Science. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2024, 14, e1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandelt, S.; Zheng, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X. Large Language Models for Intelligent Transportation: A Review of the State of the Art and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, M.; Lacivita, V.; Shin, Y.; Tarakanova, A. Accelerating Materials Property Prediction via a Hybrid Transformer Graph Framework That Leverages Four Body Interactions. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauwers, G.; Frasincar, F. A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 3279–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santana Correia, A.; Colombini, E.L. Attention, Please! A Survey of Neural Attention Models in Deep Learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 6037–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhong, G.; Yu, H. A Review on the Attention Mechanism of Deep Learning. Neurocomputing 2021, 452, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.-I.; Rhodes, O. Learning Long Sequences in Spiking Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G. Recurrent Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures, Variants, and Applications. Information 2024, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.R.; Lee, M. Transformer Architecture and Attention Mechanisms in Genome Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Review. Biology 2023, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, B. Long-Term Prediction for Temporal Propagation of Seasonal Influenza Using Transformer-Based Model. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 122, 103894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Transfer Learning for Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A.; de Vilas, T.G.; Ardila, K.; Fajardo-Rojas, F.; Pak, A.J. Machine Learning to Design Metal–Organic Frameworks: Progress and Challenges from a Data Efficiency Perspective. Mater. Horiz. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Situ, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Qiao, Z.; Ding, L.; Yang, Q. Efficient and Explainable Transformer-Based Language Models for Property Prediction in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, C.; Altundal, O.F.; Keskin, S.; Yildirim, R. Machine Learning Meets with Metal Organic Frameworks for Gas Storage and Separation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, K.-D.; Singh, A. Application of Transformers in Cheminformatics. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 4392–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Duan, L.; Jiang, J. Leveraging Machine Learning for Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Perspective. Langmuir 2023, 39, 15849–15863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashhadimoslem, H.; Abdol, M.A.; Karimi, P.; Zanganeh, K.; Shafeen, A.; Elkamel, A.; Kamkar, M. Computational and Machine Learning Methods for CO2 Capture Using Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 23842–23875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Bao, L.; Ji, Y.; Tian, Z.; Cui, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, X. Combining Machine Learning and Metal–Organic Frameworks Research: Novel Modeling, Performance Prediction, and Materials Discovery. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 514, 215888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Srinivasan, A.; Macneil, S.; Chan, J. Fluid Transformers and Creative Analogies: Exploring Large Language Models’ Capacity for Augmenting Cross-Domain Analogical Creativity. In C&C ’23: Proceedings of the Creativity and Cognition, Virtual Event, 19–23 June 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Y.G.; Haldoupis, E.; Bucior, B.J.; Haranczyk, M.; Lee, S.; Zhang, H.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Milisavljevic, M.; Ling, S.; Camp, J.S.; et al. Advances, Updates, and Analytics for the Computation-Ready, Experimental Metal–Organic Framework Database: CoRE MOF 2019. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 5985–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.S.; Iyer, S.M.; Ray, D.; Yao, Z.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Gagliardi, L.; Notestein, J.M.; Snurr, R.Q. Machine Learning the Quantum-Chemical Properties of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Accelerated Materials Discovery. Matter 2021, 4, 1578–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldblyum, J.I.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Matzger, A.J. Non-Interpenetrated IRMOF-8: Synthesis, Activation, and Gas Sorption. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lee, H.-S.; Seo, D.-H.; Cho, S.J.; Jeon, E.; Moon, H.R. Melt-Quenched Carboxylate Metal–Organic Framework Glasses. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Srinivas, K. Organic Carboxylate-Based MOFs and Derivatives for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 428, 213619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, L. Recent Advances in Naphthalenediimide-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks: Structures and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 430, 213665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Z.; Zhang, X.-D.; Zhang, Y.-K.; Wang, F.-T.; Geng, L.; Hu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.-S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X. Linker Engineering in Mixed-Ligand Metal–Organic Frameworks for Simultaneously Enhanced Benzene Adsorption and Benzene/Cyclohexane Separation. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 8101–8109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Singh, P.; Singhal, A.; Kumar, S.; Singh Gahlot, A.P.; Gandhi, N.; Kumari, P. Advances in Metal–Organic Frameworks for Water Remediation Applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3413–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Tian, J.; Chen, Q.; Hong, M. Water-Stable Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Rational Construction and Carbon Dioxide Capture. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 1570–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, B.N.; Borges, D.D.; Park, J.; Lee, J.S.; Jo, D.; Chang, J.; Cho, S.J.; Maurin, G.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, U. Tuning Hydrophilicity of Aluminum MOFs by a Mixed-Linker Strategy for Enhanced Performance in Water Adsorption-Driven Heat Allocation Application. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giappa, R.M.; Papadopoulos, A.G.; Klontzas, E.; Tylianakis, E.; Froudakis, G.E. Linker Functionalization Strategy for Water Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Molecules 2022, 27, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.H.; Shim, H.S.; Ha, J.; Moon, H.R. MOF-on-MOF Architectures: Applications in Separation, Catalysis, and Sensing. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2021, 42, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, A.; Liu, J.-Q. Prospects, Advances and Biological Applications of MOF-Based Platform for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 3725–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Wang, K.-Y.; Liang, R.-R.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Mao, Y.; Huo, J.; Shi, W.; Zhou, H.-C. Modular Construction of Multivariate Metal–Organic Frameworks for Luminescent Sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 3866–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinstry, C.; Cussen, E.J.; Fletcher, A.J.; Patwardhan, S.V.; Sefcik, J. Effect of Synthesis Conditions on Formation Pathways of Metal Organic Framework (MOF-5) Crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 5481–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, M.A.; Abbas, Q.; Mouselly, M.; Alawadhi, H.; Olabi, A.G. High-Performance Effective Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrochemical Applications. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2022, 7, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Lahtinen, M. 3D Zinc–Organic Frameworks Based on Mixed Thiophene Dicarboxylate and 4-Amino-3,5-Bis(4-Pyridyl)-1,2,4-Triazole Linkers: Syntheses, Structural Diversity, and Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Transformations. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemenčič, K.; Krajnc, A.; Puškarić, A.; Huš, M.; Marinič, D.; Likozar, B.; Logar, N.Z.; Mazaj, M. Amine-Functionalized Triazolate-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Enhanced Diluted CO2 Capture Performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202424747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-López, L.; Arcís-Castillo, Z.; Muñoz, M.C.; Real, J.A. Clathration of Five-Membered Aromatic Rings in the Bimetallic Spin Crossover Metal–Organic Framework [Fe(TPT)2/3{MI(CN)2}2]·G (MI = Ag, Au). Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 6311–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Sánchez, M.; Turo-Cortés, R.; Bartual-Murgui, C.; da Silva, I.; Muñoz, M.C.; Real, J.A. Enhanced Interplay between Host–Guest and Spin-Crossover Properties through the Introduction of an N Heteroatom in 2D Hofmann Clathrates. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 11866–11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runowski, M.; Marcinkowski, D.; Soler-Carracedo, K.; Gorczyński, A.; Ewert, E.; Woźny, P.; Martín, I.R. Noncentrosymmetric Lanthanide-Based MOF Materials Exhibiting Strong SHG Activity and NIR Luminescence of Er3+: Application in Nonlinear Optical Thermometry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 3244–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyanfar, N.; Ahmadi, M.; Ayyoubzadeh, S.M.; Ghorbani-Bidkorpeh, F. Drug Delivery System Tailoring via Metal-Organic Framework Property Prediction Using Machine Learning: A Disregarded Approach. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Ke, G.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, Z.; Lu, D. Metal-Organic Frameworks Meet Uni-MOF: A Transformer-Based Gas Adsorption Detector. ChemRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z.; Liu, D. Synthesis and Applications of Isoreticular Metal–Organic Frameworks IRMOFs- n (n = 1, 3, 6, 8). Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 7439–7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Lu, L. Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework-3 (IRMOF-3): From Experimental Preparation, Functionalized Modification to Practical Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A. Large-Scale Free Energy Calculations on a Computational Metal–Organic Frameworks Database: Toward Synthetic Likelihood Predictions. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 8106–8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Jeong, H.-K. Generation of Covalently Functionalized Hierarchical IRMOF-3 by Post-Synthetic Modification. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181–182, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Argandona, S.M.; Melle, F.; Rampal, N.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. Advances in Surface Functionalization of Next-Generation Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications: Design, Strategies, and Prospects. Chem 2024, 10, 504–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.; Javanbakht, S.; Mohammadi, R. Encapsulation of NH2-MIL-101(Fe) with Dialdehyde Starch through Schiff-Base Imine: A Development of a PH-Responsive Core-Shell Fluorescent Nanocarrier for Doxorubicin Delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, L.; Cheng, F.; Luo, F. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Xenon and Krypton Separation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, A.; Coudert, F.-X.; Rogge, S.M.J.; Heydenrych, G.; Fan, D.; Sarikas, A.P.; Keskin, S.; Maurin, G.; Froudakis, G.E.; Wuttke, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Paradigms for Next-Generation Metal–Organic Framework Research. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 23367–23380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, S.; Islam, N.U.; Uddin, Z.; Cheema, K.M.; Ahmed, S.S.; Khan, M.F. Deep Ensemble Learning with Transformer Models for Enhanced Alzheimer’s Disease Detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Kim, J. Property-Guided Inverse Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks Using Quantum Natural Language Processing. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilania, G. Machine Learning in Materials Science: From Explainable Predictions to Autonomous Design. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 193, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, X.; Cao, Y.-C.; Cheng, S. Artificial Intelligence to Power the Future of Materials Science and Engineering. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 1900143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.; Sun, M.; Huang, B. Application of Machine Learning for Advanced Material Prediction and Design. EcoMat 2022, 4, e12194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Liu, W.; Huang, C.; Mei, T. A Review of Performance Prediction Based on Machine Learning in Materials Science. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaam, A.R.A.; Greeni, A.B.; Arockiaraj, M. Modified Reverse Degree Descriptors for Combined Topological and Entropy Characterizations of 2D Metal Organic Frameworks: Applications in Graph Energy Prediction. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1470231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Automated Graph Neural Networks Accelerate the Screening of Optoelectronic Properties of Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Greenberg, J.; Zhao, X.; Hu, X.; McCLellan, S.; Kalinowski, A.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Langlois, K.; Furst, J.; Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A.; et al. Building Open Knowledge Graph for Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOF-KG): Challenges and Case Studies. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04502. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, K.; Yildirim, T.; Siderius, D.W.; Kusne, A.G.; McDannald, A.; Ortiz-Montalvo, D.L. Graph Neural Network Predictions of Metal Organic Framework CO2 Adsorption Properties. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 210, 111388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z. Attention-Based Interpretable Multiscale Graph Neural Network for MOFs. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025, 21, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Wolverton, C. Developing an Improved Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network Framework for Accelerated Materials Discovery. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 063801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Grossman, J.C. Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for an Accurate and Interpretable Prediction of Material Properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, S.; Mayr, F.; Thomas, S.; Gagliardi, A.; Zavadlav, J. Active Learning Graph Neural Networks for Partial Charge Prediction of Metal-Organic Frameworks via Dropout Monte Carlo. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omee, S.S.; Louis, S.-Y.; Fu, N.; Wei, L.; Dey, S.; Dong, R.; Li, Q.; Hu, J. Scalable Deeper Graph Neural Networks for High-Performance Materials Property Prediction. Patterns 2022, 3, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, B.; Zhou, K.; Wu, J.; Song, K. High-Throughput Prediction of Metal-Embedded Complex Properties with a New GNN-Based Metal Attention Framework. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 2350–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah Khan, M.; Alissa, M.; Inam, M.; Alsuwat, M.A.; Abdulaziz, O.; Mostafa, Y.S.; Hussain, T.; ur Rehman, K.; Zaman, U.; Khan, D. Comprehensive Overview of Utilizing Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Precise Cancer Drug Delivery. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 111056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Sim, Y.; Yang, G.; Park, M.-H.; Kim, K.; Ryu, J.-H. Surface Functionalization of Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticle for Overcoming Biological Barrier in Cancer Therapy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3119–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hong, Z. A Review on the Applications of Graph Neural Networks in Materials Science at the Atomic Scale. Mater. Genome Eng. Adv. 2024, 2, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouichaoui, A.R.N.; Fan, F.; Abildskov, J.; Sin, G. Application of Interpretable Group-Embedded Graph Neural Networks for Pure Compound Properties. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 176, 108291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, P.; Neubert, M.; Eberhard, A.; Torresi, L.; Zhou, C.; Shao, C.; Metni, H.; van Hoesel, C.; Schopmans, H.; Sommer, T.; et al. Graph Neural Networks for Materials Science and Chemistry. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, K.K.; Achenie, L.E.K.; Asamoah, T.; Arthur, E.K.; Asiedu, N.Y. Incorporating Mechanistic Insights into Structure–Property Modeling of Metal–Organic Frameworks for H2 and CH4 Adsorption: A CGCNN Approach. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 3764–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; He, J.; Park, S.-I.; Min, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yoo, B. SparseVoxFormer: Sparse Voxel-Based Transformer for Multi-Modal 3D Object Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08092. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, S.; Xie, E.; Chu, R.; Yao, L.; Hong, L.; Nießner, M.; Li, Z. DiT-3D: Exploring Plain Diffusion Transformers for 3D Shape Generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 67960–67971. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnapriyan, A.S.; Haranczyk, M.; Morozov, D. Topological Descriptors Help Predict Guest Adsorption in Nanoporous Materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 9360–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapriyan, A.S.; Montoya, J.; Haranczyk, M.; Hummelshøj, J.; Morozov, D. Machine Learning with Persistent Homology and Chemical Word Embeddings Improves Prediction Accuracy and Interpretability in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Nature 2020, 11, 8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Vázquez-González, M.; Willner, I. Stimuli-Responsive Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticles for Controlled Drug Delivery and Medical Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4541–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mswahili, M.E.; Jeong, Y.-S. Transformer-Based Models for Chemical SMILES Representation: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktavian, R.; Schireman, R.; Glasby, L.T.; Huang, G.; Zanca, F.; Fairen-Jimenez, D.; Ruggiero, M.T.; Moghadam, P.Z. Computational Characterization of Zr-Oxide MOFs for Adsorption Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 56938–56947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, M.; Peskov, M.A.; Ramsden, S.J.; Yaghi, O.M. The Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (RCSR) Database of, and Symbols for, Crystal Nets. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Ji, H. IMG2SMI: Translating Molecular Structure Images to Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.04202. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.F.; Goeßmann, A.; Rupp, M. Representations of Molecules and Materials for Interpolation of Quantum-Mechanical Simulations via Machine Learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Sun, Z.-Y. Is BigSMILES the Friend of Polymer Machine Learning? ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S.; Arenas-Vivo, A.; Horcajada, P. Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Novel Platform for Combined Advanced Therapies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 388, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcajada, P.; Gref, R.; Baati, T.; Allan, P.K.; Maurin, G.; Couvreur, P.; Férey, G.; Morris, R.E.; Serre, C. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1232–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Qian, X.; Fu, T.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Yan, H.; Cui, C.; Tan, W. Metal–Organic Framework Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery in Biomedical Applications. Nanomicro Lett. 2020, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.-G.; Wei, W.; Lv, P.-P.; Yue, H.; Wang, L.-Y.; Su, Z.-G.; Ma, G.-H. Surface Charge Affects Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2440–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmolo, P.; Pirone, D.; Sirico, D.G.; Miccio, L.; Bianco, V.; Ayoub, A.B.; Psaltis, D.; Ferraro, P. Loss Minimized Data Reduction in Single-Cell Tomographic Phase Microscopy Using 3D Zernike Descriptors. Intell. Comput. 2023, 2, 0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, P.Z.; Chung, Y.G.; Snurr, R.Q. Progress toward the Computational Discovery of New Metal–Organic Framework Adsorbents for Energy Applications. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, K.; Wakiuchi, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Yoshida, R. Advancing Extrapolative Predictions of Material Properties through Learning to Learn Using Extrapolative Episodic Training. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sui, Y.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Hooi, B. UniGraph2: Learning a Unified Embedding Space to Bind Multimodal Graphs. In WWW ’25: Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rogacka, J.; Labus, K. Metal–Organic Frameworks as Highly Effective Platforms for Enzyme Immobilization–Current Developments and Future Perspectives. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 4, 1273–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burner, J.; Luo, J.; White, A.; Mirmiran, A.; Kwon, O.; Boyd, P.G.; Maley, S.; Gibaldi, M.; Simrod, S.; Ogden, V.; et al. ARC–MOF: A Diverse Database of Metal-Organic Frameworks with DFT-Derived Partial Atomic Charges and Descriptors for Machine Learning. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, L.T.; Gubsch, K.; Bence, R.; Oktavian, R.; Isoko, K.; Moosavi, S.M.; Cordiner, J.L.; Cole, J.C.; Moghadam, P.Z. DigiMOF: A Database of Metal–Organic Framework Synthesis Information Generated via Text Mining. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 4510–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Tao, Z.; Xue, X.; Li, R.; Feng, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Machine Learning Accelerates the Investigation of Targeted MOFs: Performance Prediction, Rational Design and Intelligent Synthesis. Nano Today 2023, 49, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Fang, Y.; Hu, M.; Guo, S.; Sui, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. Interpretable Machine-Learning and Big Data Mining to Predict the CO2 Separation in Polymer-MOF Mixed Matrix Membranes. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2405905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Situ, Y.; Ding, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q. MOF-GRU: A MOFid-Aided Deep Learning Model for Predicting the Gas Separation Performance of Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 59887–59894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.T.; Moosavi, S.M. Connecting Metal-Organic Framework Synthesis to Applications with a Self-Supervised Multimodal Model. ChemRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, O.; Borgs, C.; Chayes, J.T.; Yaghi, O.M. ChatGPT Chemistry Assistant for Text Mining and the Prediction of MOF Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 18048–18062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, R.; Xu, R.; Ju, M.-G.; Wang, J. How to Accelerate the Inorganic Materials Synthesis: From Computational Guidelines to Data-Driven Method? Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, L.; Feng, G. Identifying MOFs for Electrochemical Energy Storage via Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H.; Keskin, S. A New Era of Modeling MOF-Based Membranes: Cooperation of Theory and Data Science. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2300225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Breunig, H.M.; Peng, P. Broad Range Material-to-System Screening of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage Using Machine Learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Gounaris, C.E. Computational Discovery of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Sustainable Energy Systems: Open Challenges. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 167, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.G.; Haldoupis, E.; Bucior, B.J.; Haranczyk, M.; Lee, S.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Ling, S.; Milisavljevic, M.; Zhang, H.; Camp, J.S. Computation-Ready Experimental Metal-Organic Framework (CoRE MOF) 2019 Dataset; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 3528250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbitt, N.S.; Shi, K.; Bucior, B.J.; Chen, H.; Tracy-Amoroso, N.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Merlin, J.H.; Siepmann, J.I.; Siderius, D.W.; et al. MOFX-DB: An Online Database of Computational Adsorption Data for Nanoporous Materials. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2023, 68, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Lan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhong, C. Exploring the Structure-Property Relationships of Covalent Organic Frameworks for Noble Gas Separations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 168, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, P.Z.; Li, A.; Wiggin, S.B.; Tao, A.; Maloney, A.G.P.; Wood, P.A.; Ward, S.C.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. Development of a Cambridge Structural Database Subset: A Collection of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Past, Present, and Future. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 2618–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P.G.; Chidambaram, A.; García-Díez, E.; Ireland, C.P.; Daff, T.D.; Bounds, R.; Gładysiak, A.; Schouwink, P.; Moosavi, S.M.; Maroto-Valer, M.M.; et al. Data-Driven Design of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Wet Flue Gas CO2 Capture. Nature 2019, 576, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Jiao, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y. Interpretable Graph Transformer Network for Predicting Adsorption Isotherms of Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 5446–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, Z.; Ahamed, F.; Mayer, W.; Patel, N.; Grossmann, G.; Stumptner, M.; Kuusk, A. Artificial Intelligence for Industry 4.0: Systematic Review of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 216, 119456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Applications-A Revolution in Modern Industries. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.B.; Kausik, M.A.K. AI Revolutionizing Industries Worldwide: A Comprehensive Overview of Its Diverse Applications. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Qi, J.; Peng, Y. Leave It to Large Language Models! Correction and Planning with Memory Integration. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Z.; Lai, Y.; Huang, R.; Bai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q. Enhancing Robot Task Planning and Execution through Multi-Layer Large Language Models. Sensors 2024, 24, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Song, K.; Tan, X.; Zhang, W.; Ren, K.; Yuan, S.; Lu, W.; Li, D.; Zhuang, Y. TaskBench: Benchmarking Large Language Models for Task Automation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 37, 4540–4574. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; Jain, A.; Tavazza, F.; Cohn, R.; Park, C.W.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A.; Billinge, S.J.L.; et al. Recent Advances and Applications of Deep Learning Methods in Materials Science. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Lin, H.; Li, M.; Ma, S.; Avdeev, M.; Shi, S. Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Applications in Materials Science: Current Situation and Future Perspectives. J. Mater. 2023, 9, 798–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, K.M.; Ai, Q.; Al-Feghali, A.; Badhwar, S.; Bocarsly, J.D.; Bran, A.M.; Bringuier, S.; Brinson, L.C.; Choudhary, K.; Circi, D.; et al. 14 Examples of How LLMs Can Transform Materials Science and Chemistry: A Reflection on a Large Language Model Hackathon. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, N.; Marrone, S.; Sansone, C. Transformers in the Real World: A Survey on NLP Applications. Information 2023, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenstein, L.; Konen, E.; Green, M.; Klang, E. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers in Radiology: A Systematic Review of Natural Language Processing Applications. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2024, 21, 914–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.; Lee, S.-T. Applications of Transformers in Computational Chemistry: Recent Progress and Prospects. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Nie, Z. Application of Machine Learning in Material Synthesis and Property Prediction. Materials 2023, 16, 5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, J. ChatMOF: An Artificial Intelligence System for Predicting and Generating Metal-Organic Frameworks Using Large Language Models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-H.; Kong, F.; Liu, B.-F.; Ren, N.-Q.; Ren, H.-Y. Preparation Strategies of Waste-Derived MOF and Their Applications in Water Remediation: A Systematic Review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 533, 216534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.D.; Vu, N.-N.; Hoang, T.L.G.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Materials for Photocatalytic Antibacterial Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 523, 216298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kang, Y.; Bae, T.; Bernales, V.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Kim, J. EGMOF: Efficient Generation of Metal-Organic Frameworks Using a Hybrid Diffusion-Transformer Architecture. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.03122. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodríguez, C.F.; Guzmán-Sastoque, P.; Rodríguez, J.E.; Sanchez-Hernandez, W.; Cruz, J.C. From Words to Frameworks: Transformer Models for Metal–Organic Framework Design in Nanotheranostics. J. Nanotheranostics 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010003

Rodríguez CF, Guzmán-Sastoque P, Rodríguez JE, Sanchez-Hernandez W, Cruz JC. From Words to Frameworks: Transformer Models for Metal–Organic Framework Design in Nanotheranostics. Journal of Nanotheranostics. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez, Cristian F., Paula Guzmán-Sastoque, Juan Esteban Rodríguez, Wilman Sanchez-Hernandez, and Juan C. Cruz. 2026. "From Words to Frameworks: Transformer Models for Metal–Organic Framework Design in Nanotheranostics" Journal of Nanotheranostics 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010003

APA StyleRodríguez, C. F., Guzmán-Sastoque, P., Rodríguez, J. E., Sanchez-Hernandez, W., & Cruz, J. C. (2026). From Words to Frameworks: Transformer Models for Metal–Organic Framework Design in Nanotheranostics. Journal of Nanotheranostics, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010003