Digital Resilience and the “Awareness Gap”: An Empirical Study of Youth Perceptions of Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms in Hungary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Equal access to justice (Target 16.3), which in the digital sphere translates to users’ ability to understand platform rules and access effective remedies against content moderation decisions;

- The protection of fundamental freedoms (Target 16.10), which involves balancing freedom of expression with protection from harm, a task complicated when users lack awareness of their rights and responsibilities online.

2. Theoretical Background and Platform Governance

2.1. Definitional Challenges of Hate Speech in International and European Law

2.2. Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms

2.3. A Proposed Operational Definition for Hate Speech Research

2.4. Moderation and Appeals: Meta’s Internal “Legal Order”

3. Materials and Methods

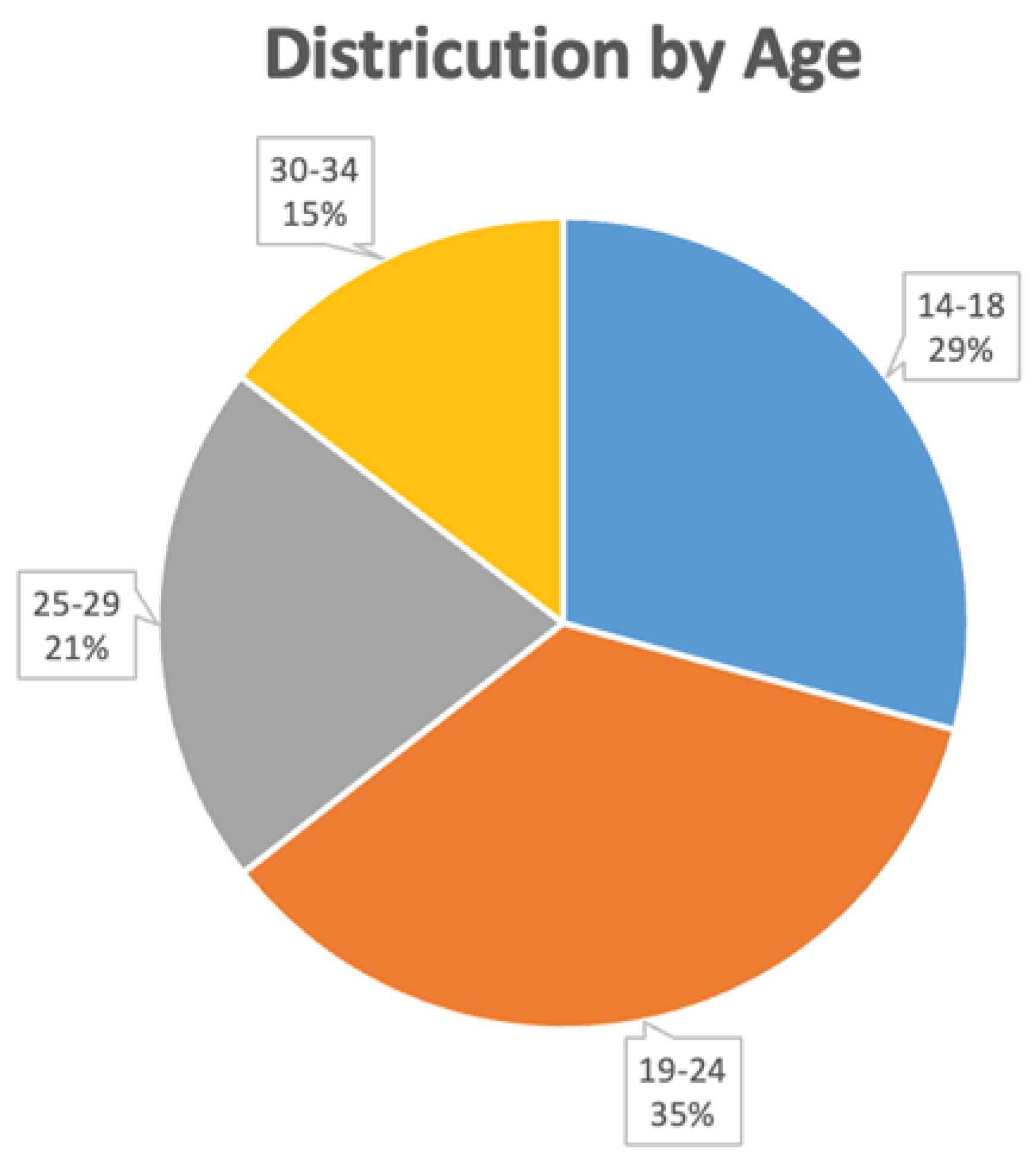

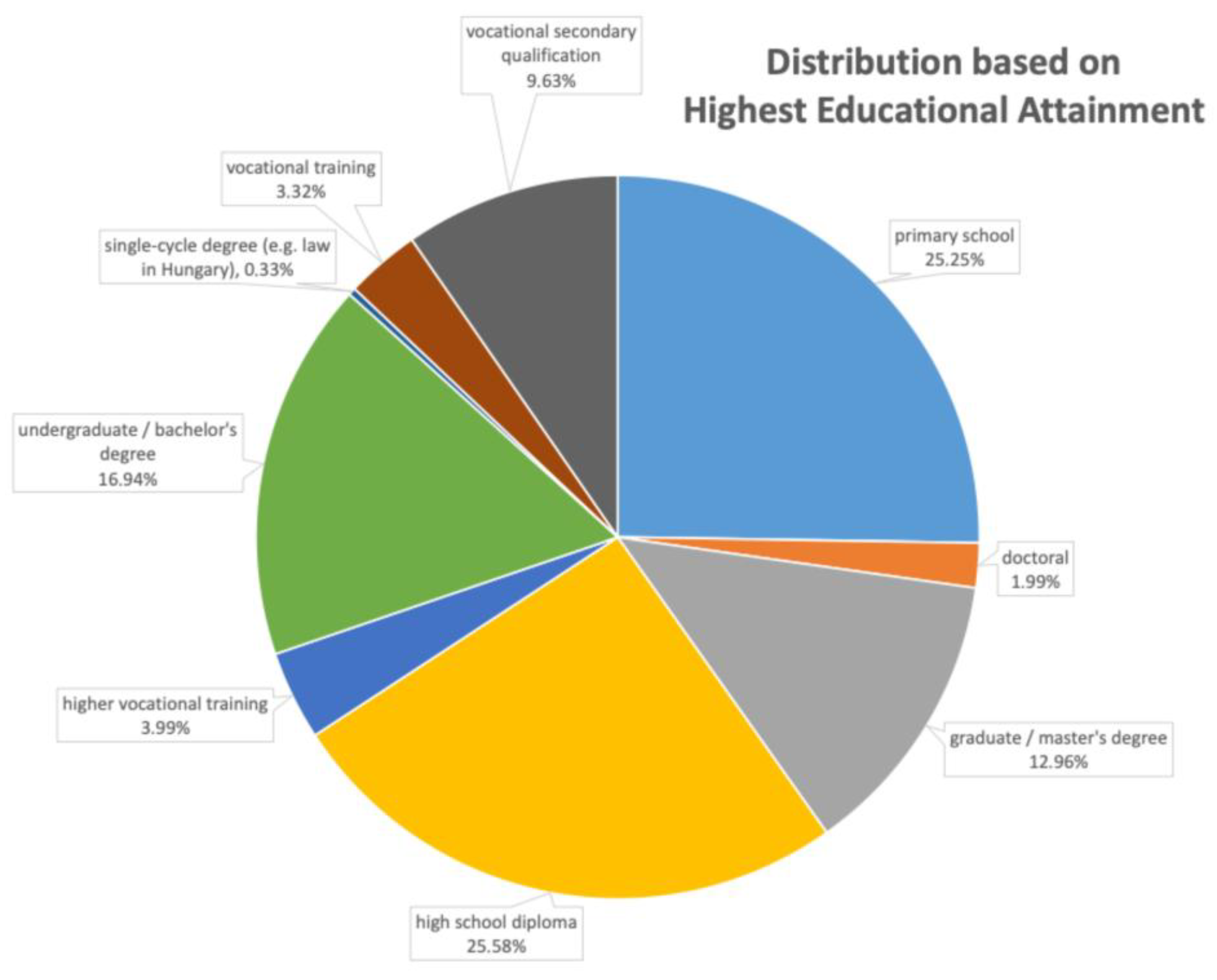

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Survey Instrument and Case Studies

- Negative stereotypes about African Americans: This case was adapted to stereotypes concerning the Roma community to fit the Hungarian social context.

- Hate-inciting meme video montage: A video featuring antisemitic, anti-LGBTIQ+, and other discriminatory content.

- Holocaust denial: An Instagram post that questioned the facts of the Holocaust.

- Post targeting transgender individuals: A post that incited transgender people to commit suicide.

- Dehumanizing speech against a woman: A post that objectified a woman and used offensive language.

3.3. Hypotheses

- H0A: Young Hungarian Facebook users do not recognize posts containing hate speech.

- H0B: Hungarian consumers would not sanction posts containing hate speech accordingly (i.e., in line with Meta’s decision).

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Findings on Conceptual Awareness

4.2. Hypothesis Testing: Recognition of Hate Speech (H0A)

4.3. Hypothesis Testing: Sanctioning Preferences (H0B)

5. Discussion

5.1. Situating the “Awareness Gap” Within Systemic Regulatory Divergences

5.2. Policy Implications and Recommendations

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| DSA | Digital Services Act |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| UDHR | Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

| ICCPR | International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

| ECHR | European Convention on Human Rights |

| ECtHR | European Court of Human Rights |

| LGBTIQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer |

Appendix A

| t-Test: One-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | |

| Mean | 214.8 | 0 |

| Variance | 3108.2 | 0 |

| Observations | 5 | 2 |

| Hypothesized Mean | 151 | |

| df | 4 | |

| t Stat | 2.558887559 | |

| P(T ≤ t) one-tail | 0.031355958 | |

| t Critical one-tail | 2.131846786 | |

| P(T ≤ t) two-tail | 0.062711916 | |

| t Critical two-tail | 2.776445105 |

Appendix B

| t-Test: One-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | |

| Mean | 247.4 | 0 |

| Variance | 196.3 | 0 |

| Observations | 5 | 2 |

| Hypothesized Mean | 151 | |

| df | 4 | |

| t Stat | 15.3851554 | |

| P(T ≤ t) one-tail | 0.00005207 | |

| t Critical one-tail | 2.131846786 | |

| P(T ≤ t) two-tail | 0.000104138 | |

| t Critical two-tail | 2.776445105 |

References

- Gopal, R.; Hojati, A.; Patterson, R.A. A Little Bit Goes a Long Way: Indirect Effects of Content Moderation on Online Social Media. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2025, 29, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, A.; Maltseva, K.; Fieseler, C.; Fleck, M. Muzzling social media: The adverse effects of moderating stakeholder conversations online. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.; Gonçalves, J.; Masullo, G.; Da Silva, M.; Hofhuis, J. Who Can Say What? Testing the Impact of Interpersonal Mechanisms and Gender on Fairness Evaluations of Content Moderation. Soc. Media + Soc. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozo, A.Z.; Campo-Archbold, A.; Díaz-López, D.; Gray, I.; Pastor-Galindo, J.; Nespoli, P.; Mármol, F.G.; McCoy, D. Cyber democracy in the digital age: Characterizing hate networks in the 2022 US midterm elections. Inf. Fusion 2024, 110, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Niker, F. What Social Media Facilitates, Social Media should Regulate: Duties in the New Public Sphere. Political Q. 2021, 92, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytac, U. Digital Domination: Social Media and Contestatory Democracy. Political Stud. 2022, 72, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Kou, Y. “How advertiser-friendly is my video?”: YouTuber’s Socioeconomic Interactions with Algorithmic Content Moderation. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Are, C.; Briggs, P. The Emotional and Financial Impact of De-Platforming on Creators at the Margins. Soc. Media + Soc. 2023, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malki, L.M.; Patel, D.; Singh, A. “The Headline Was So Wild That I Had To Check”: An Exploration of Women’s Encounters With Health Misinformation on Social Media. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, J. Digital platforms as entangled infrastructures: Addressing public values and trust in messaging apps. Eur. J. Commun. 2021, 36, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, S.; Zheng, Z.; Fu, F. Public discourse and social network echo chambers driven by socio-cognitive biases. Phys. Rev. X 2020, 10, 041042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.; Schill, D. Sophisticated Hate Stratagems: Unpacking the Era of Distrust. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 68, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windisch, S.; Wiedlitzka, S.; Olaghere, A.; Jenaway, E. Online interventions for reducing hate speech and cyberhate: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daruwala, N.A. Social media, expression, and online engagement: A psychological analysis of digital communication and the chilling effect in the UK. Front. Commun. 2025, 10, 1565289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nölleke, D.; Leonhardt, B.; Hanusch, F. “The chilling effect”: Medical scientists’ responses to audience feedback on their media appearances during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Underst. Sci. 2023, 32, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosztonyi, G. Challenges of Monitoring Obligations in the European Union’s Digital Services Act. Elte Law J. 2024, 2024, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawono, B.T.; Glaser, H. The Urgency of Restorative Justice Regulation on Hate Speech. Bestuur 2024, 11, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, O.; Turenne, S. The regulation of hate speech online and its enforcement—A comparative outlook. J. Media Law 2022, 14, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.; Batista, F.; Ribeiro, R.; Fialho, P.; Moro, S.; Fonseca, A.; Guerra, R.; Carvalho, P.; Marques, C.; Silva, C. A comprehensive review on automatic hate speech detection in the age of the transformer. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogwa, N.; Ezeibe, C. The state, hate speech regulation and sustainable democracy in Africa: A study of Nigeria and Kenya. Afr. Identities 2020, 20, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.A.; Montero-Díaz, J.; Moreno-Delgado, A. Hate Speech: A Systematized Review. Sage Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, A.I.; Laforgue-Bullido, N.; Abril-Hervás, D. Hate speech: A systematic review of scientific production and educational considerations. Rev. Fuentes 2022, 24, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Szépvölgyi, E.; Tóth, D.A.; Kelemen, R. From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being. Societies 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjin-Tettey, T.D. Combating Fake News, Disinformation, and Misinformation: Experimental Evidence for Media Literacy Education. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2022, 9, 2037229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M.; Rúas-Araújo, J.; Horowitz, M. Beyond Online Disinformation: Assessing National Information Resilience in Four European Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, R.; Squillace, J.; Németh, R.; Cappella, J. The Impact of Digital Inequality on IT Identity in the Light of Inequalities in Internet Access. Elte Law J. 2024, 2024, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) Article 19. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) Article 12. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Article 19. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Article 20. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Preamble. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/convention_ENG (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Article 19. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/convention_ENG (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Article 10. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/convention_ENG (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) Article 17. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/convention_ENG (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Magyar Tartalomszolgáltatók Egyesülete and Index.hu Zrt. v. Hungary No. 22947/13, ECHR, 2016. Available online: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-160314%22]} (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Delfi AS v. Estonia, 64569/09, ECHR, 2015. Available online: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-155105%22]} (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Oster, J. Media Freedom as a Fundamental Right; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottiaux, S. Conflicting Conceptions of Hate Speech in the ECtHR’s Case Law. Ger. Law J. 2022, 23, 1193–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treaty of the European Union. Article 6. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2bf140bf-a3f8-4ab2-b506-fd71826e6da6.0023.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000/C 364/01) Article 11. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000/C 364/01) Article 52. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Koltay, A. A Szólásszabadság Alapvonalai; Századvég Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Expert Workshops on the Prohibition of Incitement to National, Racial or Religious Hatred. 2012, p.6. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Rabat_draft_outcome.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Expert Workshops on the Prohibition of Incitement to National, Racial or Religious Hatred. 2012, p.10. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Rabat_draft_outcome.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Expert Workshops on the Prohibition of Incitement to National, Racial or Religious Hatred. 2012, p.9. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Rabat_draft_outcome.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Fino, A. Defining Hate Speech. J. Int. Crim. Justice 2020, 18, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, M.; Vilar-Lluch, S.; Borg, E.; Hansen, N. What is Hate Speech? The Case for a Corpus Approach. Crim. Law Philos. 2023, 18, 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Lluch, S. Understanding and appraising ‘hate speech’. J. Lang. Aggress. Confl. 2023, 11, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučković, J.; Lučić, S. HATE SPEECH AND SOCIAL MEDIA. TEME 2023, 47, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkiviadou, N. Platform liability, hate speech and the fundamental right to free speech. Inf. Commun. Technol. Law 2024, 34, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market for Digital Services Amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022R2065 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kovács, G. A nyomozás a gyakorlatban—A kezdeti lépésektől a nyomozás tervezéséig és szervezéséig. Magy. Bűnüldöző 2014, 2014, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Pál, G. A gyűlöletbeszéd fogalma: A politikai vitában. Értelmezések és alkalmazások. Polit. Tanulmányok 2012, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Vejdeland and Others v. Sweden, No. 1813/07, ECHR 2012. Available online: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-109046%22]} (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 1964. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/376/254/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Conference of Presidents of Parliament. Women in politics and in the public discourse: What role can national Parliaments play in combating the increasing level of harassment and hate speech towards female politicians and parliamentarians? Strasbourg, France, 24–25 October 2019. Available online: https://edoc.coe.int/en/violence-against-women/7989-women-in-politics-and-in-the-public-discourse.html?fbclid=IwY2xjawO33vRleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFzc0RraU9iTGVNd2tpc3FRc3J0YwZhcHBfaWQQMjIyMDM5MTc4ODIwMDg5MgABHsVOwUKB9rMxBcxOqs54hUDKCr-8ejJEJC6QvTKWAWgowN7BtvgXRugX_Dh5_aem__lSEB6D4ECuvHJ0DGVG7qQ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Abokhodair, N.; Skop, Y.; Rüller, S.; Aal, K.; Elmimouni, H. Opaque algorithms, transparent biases: Automated content moderation during the Sheikh Jarrah Crisis. First Monday 2024, 29, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson-Salahuddin, C. Repairing the harm: Toward an algorithmic reparations approach to hate speech content moderation. Big Data Soc. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market for Digital Services Amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act). Article 20. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022R2065 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Gulati, R. Meta’s Oversight Board and Transnational Hybrid Adjudication—What Consequences for International Law? Ger. Law J. 2023, 24, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douek, E. The Meta Oversight Board and the Empty Promise of Legitimacy. Harv. JL Tech. 2023, 37, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Floridi, L. Meta’s Oversight Board: A Review and Critical Assessment. Minds Mach. 2023, 33, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazúr, J.; Grambličková, B. New Regulatory Force of Cyberspace: The Case of Meta’s Oversight Board. Masaryk. Univ. J. Law Technol. 2023, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggart, B.; Iglesias Keller, C. Democratic legitimacy in global platform governance. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.; Sarapin, S. You can’t block me: When social media spaces are public forums. First Amend. Stud. 2020, 54, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaretnam, T. Statistics for Social Sciences, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- D O’Gorman, K.; MacIntosh, R. Research Methods for Business and Management: A Guide to Writing Your Dissertation; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hietanen, M.; Eddebo, J. Towards a Definition of Hate Speech—With a Focus on Online Contexts. J. Commun. Inq. 2022, 47, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinpeng, A.; Martin, F.; Gelber, K.; Shields, K. Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific; The University of Sydney and The University of Queensland: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, A. Regulating Online Hate Speech through the Prism of Human Rights Law: The Potential of Localised Content Moderation. In The Australian Year Book of International Law Online; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, M.A. Adaptive Folk Theorization as a Path to Algorithmic Literacy on Changing Platforms. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.C. Algorithmic resistance as political disengagement. Media Int. Aust. 2022, 183, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Oscillation Between Resist and to Not? Users’ Folk Theories and Resistance to Algorithmic Curation on Douyin. Soc. Media + Soc. 2025, 11, 20563051251313610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.A.; Yakhmi, S.; Iyer, T.P.; Strasnick, E.; Zhang, A.X.; Bernstein, M.S. Comparing the Perceived Legitimacy of Content Moderation Processes: Contractors, Algorithms, Expert Panels, and Digital Juries. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, P. Sanctioning hate speech on the Internet: In search of the best approach. Prav. Zapisi 2023, 14, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrand, B. ‘Is This a Hate Speech?’ The Difficulty in Combating Radicalisation in Coded Communications on Social media Platforms. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2023, 29, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, G. Democratising online content moderation: A constitutional framework. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2020, 36, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintais, J.P.; Appelman, N.; Fathaigh, R.Ó. Using Terms and Conditions to apply Fundamental Rights to Content Moderation. Ger. Law J. 2023, 24, 881–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, H.N. Transitional justice and online social platforms: Facebook and the Rohingya genocide. Int. J. Law Inf. Technol. 2023, 31, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchik, A.V. Disappearing acts: Content moderation and emergent practices to preserve at-risk human rights–related content. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 1527–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Cazzamatta, R.; Napolitano, C.J. Holding platforms accountable in the fight against misinformation: A cross-national analysis of state-established content moderation regulations. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2025, 87, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Szépvölgyi, E.; Cs Kiss, Z. Mind the Net: Parental Awareness and State Responsibilities in the Age of Grooming. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Clark, S.; Marshall, K.; MacLachlan, M. A Just Digital framework to ensure equitable achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Challenge | Description |

|---|---|

| No universal definition | Varies by country, court, and context |

| Free speech vs. harm | Risk of overbroad or under-protective laws |

| Subjectivity/context | Intent, audience, and culture affect interpretation |

| Distinction from offense/defamation | Difficult to draw clear legal boundaries |

| Digital/operational enforcement | Automated systems struggle with legal nuance |

| Response Type | Count (n) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| At least one correct answer | 113 | 37.5 |

| Both correct answers | 48 | 15.9 |

| Case Study | Recognition (“Yes” Responses, %) |

|---|---|

| Case 1 (Roma ethnicity) | 137 |

| Case 2 (Meme video) | 271 |

| Case 3 (Holocaust denial) | 209 |

| Case 4 (Transgender individuals) | 266 |

| Case 5 (Violence against a woman) | 191 |

| Sanction Outcome | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | 49 | 48 | 60 | 74 | 37 |

| Incorrect | 252 | 253 | 241 | 227 | 264 |

| More Lenient | 125 | 84 | 129 | 79 | 195 |

| More Severe | 127 | 169 | 112 | 148 | 69 |

| Feature | Legal Frameworks | Platform Governance | Implication for Users (as Identified in the Literature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope of Definition | Typically narrow (incitement to violence/discrimination). Constrained by free speech rights. | Generally broader, covering “offensive” content not legally proscribed. | Confusion and “Over-removal”: Users find content removed that would be legally permissible. |

| Enforcement | Requires due process, judicial review. Slower. | Rapid and less transparent. Relies on automated systems and internal policies. | Lack of Predictability and Fairness: Decisions seem arbitrary; users feel disempowered by the opaque process. |

| Standardization | Jurisdiction-specific but based on established legal principles. | Aims for global uniformity but often struggles with local context. | Inconsistent Outcomes: Similar content may be treated differently across platforms or regions, leading to user frustration. |

| Policy Recommendation | Addressed Problem (Root Cause of the “Gap”) | Corresponding SDG 16 Target |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Increasing Regulatory Transparency | Legitimacy Deficit & Algorithmic Opacity: User distrust in opaque, “black box” governance models that lack democratic input and accountability. | Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. Target 16.10: Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms. |

| 2. Transparency of Sanctions & Remedies | Procedural Injustice & User Disempowerment: Inconsistent enforcement, lack of effective remedies, and destruction of evidence, leading to user frustration and “reporting fatigue”. | Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice for all. |

| 3. Raising Awareness as a Shared Responsibility | Political Disengagement & Digital Resignation: Users’ withdrawal from active participation due to a sense of powerlessness and a breakdown of trust between individuals and institutions. | Overarching Goal of SDG 16: Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kelemen, R.; Bosits, D.; Réti, Z. Digital Resilience and the “Awareness Gap”: An Empirical Study of Youth Perceptions of Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms in Hungary. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010003

Kelemen R, Bosits D, Réti Z. Digital Resilience and the “Awareness Gap”: An Empirical Study of Youth Perceptions of Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms in Hungary. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKelemen, Roland, Dorina Bosits, and Zsófia Réti. 2026. "Digital Resilience and the “Awareness Gap”: An Empirical Study of Youth Perceptions of Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms in Hungary" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010003

APA StyleKelemen, R., Bosits, D., & Réti, Z. (2026). Digital Resilience and the “Awareness Gap”: An Empirical Study of Youth Perceptions of Hate Speech Governance on Meta Platforms in Hungary. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010003