Abstract

The increasing volume of digital medical data offers substantial research opportunities, though its complete utilization is hindered by ongoing privacy and security obstacles. This proof-of-concept study explores and confirms the viability of using Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) to ensure protection and integrity of sensitive patient data, allowing the construction of clinical trial cohorts. Our findings reveal that SMPC facilitates collaborative data analysis on distributed, private datasets with negligible computational costs and optimized data partition sizes. The established architecture incorporates patient information via a blockchain-based decentralized healthcare platform and employs the MPyC library in Python for secure computations on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)-format data. The outcomes affirm SMPC’s capacity to maintain patient privacy during cohort formation, with minimal overhead. It illustrates the potential of SMPC-based methodologies to expand access to medical research data. A key contribution of this work is eliminating the need for complex cryptographic key management while maintaining patient privacy, illustrating the potential of SMPC-based methodologies to expand access to medical research data by reducing implementation barriers.

1. Introduction

The significant growth of available data in the healthcare sector has led to significant medical advancements, heightening patient safety, enhancing diagnostics, and improving efficiency, just to name a few of the benefits [1]. This has been fueled by the large-scale adoption of Eletronic Health Records (EHR) [2], with reports of as much as 85% of European healthcare facilities having adopted EHRs [3], and similar values for US hospitals [4]. Furthermore, the aggregation of these data on a large scale presents significant potential, enabling the conduct of comprehensive research and studies grounded in big data [5,6]. For instance, Wood et al. report that access to EHRs covering 96% of England’s population allowed a cohort study to assess possible correlation between COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease on a population of 54.4 million people [7]. Similar large-scale nationwide cohort studies include [8,9].

Nonetheless, a variety of issues continue to arise regarding the privacy and security of healthcare data [10]. Within the contemporary healthcare setting, balancing the protection of patient data privacy and security with the efficient use of this data for research is becoming progressively challenging [10,11]. It is therefore of the utmost importance to study and assess methodologies for secure and privacy-aware sharing of health data. Studies on blockchain and new encryption methods are part of the efforts to tackle these challenges. Research focusing on blockchain technology typically deals with anti-tampering issues and the advantages of decentralization [12], whereas encryption initiatives utilize advances in cryptography to handle confidentiality and privacy concerns [13]. While these approaches are yielding promising outcomes, they overlook more intricate situations such as the complex process of creating clinical trial cohorts. This process involves data from various institutions that, although interoperable at the data model layer due to standards like FHIR, are not interoperable at the infrastructure layer, which restricts the implementation of advanced cryptographic techniques.

This study investigates the potential of employing Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) for the formation of clinical trial cohorts from private patient data, focusing on the privacy requirement. Thus, our primary aim is to assess the efficacy of utilizing the SMPC protocol for accessing patient medical data, all the while preserving its privacy and confidentiality. To achieve this, we have executed a proof of concept using Python with the MPyC Python library. Our methodology necessitates the involvement of several stakeholders, each motivated by distinct economic interests, potentially influencing the practicality and implementation of SMPC in clinical contexts.

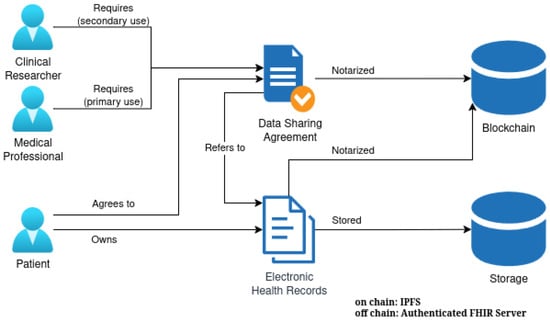

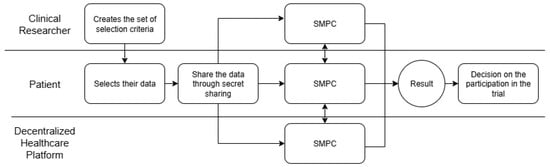

This work is part of a larger research effort aimed at developing a decentralized, blockchain-based healthcare platform. Figure 1 shows the components of this broader architecture that are relevant to the present study, which employs the notarization of EHR on a blockchain and incorporates Data Sharing Agreements (DSAs) for various use cases, such as primary care by medical professionals and secondary uses by clinical researchers.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the decentralized healthcare platform.

While the full decentralized platform is still under research and development, the present study operates under the following assumptions regarding key architectural components: (1) patients maintain full sovereignty over their data through blockchain-based identity and access control mechanisms; (2) medical data is stored securely at each healthcare institution (e.g., in FHIR servers with encrypted records), with institutions acting as data custodians rather than data controllers; (3) data sharing agreements, implemented as smart contracts or similar programmable access policies, govern access to patient data and delegate specific actions on the patient’s behalf; and (4) delegated actions preserve medical data confidentiality and privacy through cryptographic techniques such as account abstraction and secure enclaves [14,15].

For the purposes of this work, the required functionality from such a platform comprises: an authentication and authorization interface that verifies patient consent and access permissions; a secure query interface that allows authorized parties to request cohort identification without accessing raw medical records; and a verifiable audit trail of all data access requests. The focus of this study is specifically on evaluating whether SMPC can feasibly support privacy-preserving cohort identification under these assumptions, while the broader platform architecture remains a subject of ongoing research.

The main contribution of this work is centered around the assessment of the benefits and challenges from resorting to SMPC for anonymously sharing sensitive data of EHRs. For this purpose, a proof-of-concept is devised and tested.

This paper is organized in the following remaining sections: Section 2 provides an overview of SMPC, detailing its fundamental elements and introducing the challenges associated with healthcare data management. Section 3 elaborates on the formulation of our proof-of-concept, detailing the architectural and implementation decisions made. Section 4 presents the outcomes of our proof-of-concept analysis. Section 5 reflects on the of results and discusses the main limitations of SMPC. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and suggests avenues for future research.

2. Background

In this section, we discuss the fundamental principles to enhance comprehension of the broader concepts associated with the proposed research, namely SMPC.

2.1. Secret Sharing

One of the basis of SMPC is secret sharing that allows data, called the secret, to be shared by separating it in n shares [16]. This cryptographic technique divides the secret into multiple shares, ensuring that no individual share reveals any information about the original secret. Reconstruction of the secret is only possible when a sufficient number of shares are combined, at least t out of n. This method ensures privacy, as subsets with fewer than t shares provide no information about the secret.

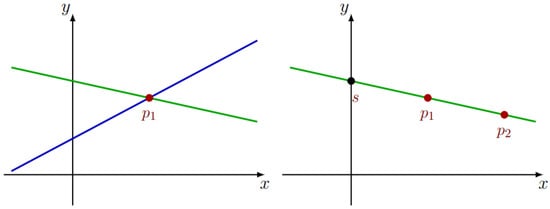

Shamir [17] proposed a -secret sharing scheme that represents the secret as the constant term () of a polynomial of degree . Each share corresponds to a point on this polynomial, and the secret can be revealed by interpolating the polynomial with at least t shares. Figure 2 illustrates this concept with a simple example where the secret is shared using a degree 1 polynomial. To determine the polynomial, and therefore uncover the secret, at least two shares (points , and ) are required. If only one point is known, the secret remains indeterminate due to the infinite number of possible polynomials that could pass through that point.

Figure 2.

Shamir Secret Sharing example.

Another commonly used scheme is additive secret sharing, where the secret is the sum of all shares [18]. As implied by its designation, this cryptographic approach involves splitting a secret into several parts, distributing each portion to various participants. The collective sum of these segments corresponds to the initial secret. It is impossible to uncover the secret without having knowledge of all parts. For example, when involving three individuals, A, B, and C, and the secret to be distributed is the integer 20, each participant receives a distinct integer such that their sum equals 20. One way to divide the secret could be assigning , , and , resulting in the total sum of 20.

2.2. Circuits

Circuits [19] form the basis for SMPC protocols because it is possible to represent a function using a circuit. Circuits comprise gates that represent operations and wires that represent paths that transport values. Circuits can be boolean or arithmetic, depending on the values that they carry.

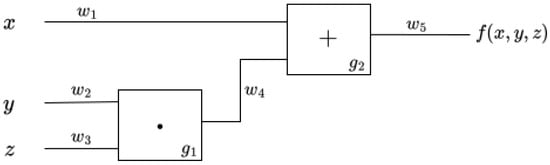

Figure 3 represents an arithmetic circuit designed to calculate the function . To obtain the result of this function, we first need to execute the multiplication gate g1. This operation gives the result of on the w4 wire, which then allows the execution of the addition gate g2. After g2, we get the final value on the output wire w5.

Figure 3.

Circuit that represents the function .

2.3. Secure Multi-Party Computation

SMPC allows a set of participants to perform jointly computations on shared data without revealing it.

In an ideal world [20], every participant would communicate with and trust a third-party to facilitate the intended computation. This entity would receive all of the inputs, compute the function that was agreed upon by them, and send the results to each one of them. In an optimal situation, all participants would access the results, ensuring both output delivery and the accurate assessment of the function, thereby confirming its correctness. Moreover, it would be infeasible for a participant to select their input reliant on another’s input, hence upholding input independence, and participants would be restricted to knowing solely their own outcomes, thereby preserving privacy. However, no trusted intermediary is present in practice, and the primary objective of SMPC protocols and their users is to overcome the limitations of the real world.

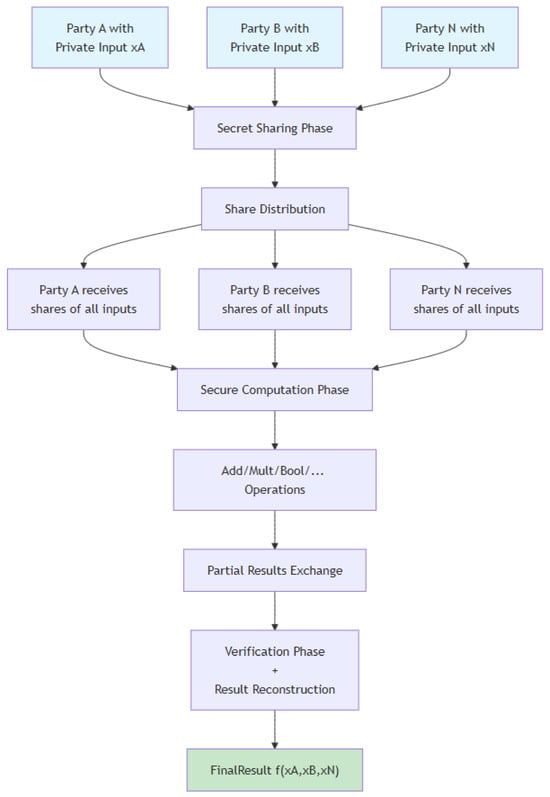

One of the first protocols to be developed for multiple participants was devised by Ben-Or, Goldwasser, and Wigderson, best known as the BGW protocol [16,21]. The protocol is structured around arithmetic circuits and follows this procedure: it commences with participants distributing their shares to one another using Shamir’s secret sharing scheme. Subsequently, each participant executes the circuit representing the agreed-upon function with the shares in their possession. Throughout execution, addition gates are computed independently, whereas for multiplication gates, participants must communicate to decrease the polynomial’s degree. After processing all gates, each participant possesses a share of the result, which they either exchange among themselves or assign to a specified participant for reconstructing the outcome. The algorithm for this protocol is detailed in Algorithm 1, and Figure 4 visually represents the key steps of the SMPC protocol.

| Algorithm 1 BGW Protocol |

Require: Participant Input, Accorded circuit

|

Figure 4.

SMPC fluxogram.

2.3.1. Security

Within the scope of executing SMPC, an entity may attempt to extract sensitive data or alter the results. This entity is known as an adversary, and it can exert control over one or more participants. Those who fall under its control are termed corrupted, whereas those who remain uninfluenced are referred to as honest participants.

Each SMPC protocol is linked to a specific security model [16,18] that specifies the capabilities of an adversary, including the permitted actions and the extent of participant corruption. In the context of an adversary’s capabilities, two crucial aspects need consideration: the classification of adversaries and the methodology for corruption. With reference to adversary classification, there are primarily two categories: semi-honest and malicious [20]. An adversary described as semi-honest, or honest-but-curious, adheres to the protocol regulations while trying to glean as much information as possible from accessible sources, like participant messages under their influence. Conversely, a malicious adversary disregards protocol constraints and can deviate unpredictably. The main models for corruption strategies include static, adaptive, and proactive security [20]. In the static model, participants are classified as either corrupt or honest from the onset and maintain these roles throughout the protocol’s execution. Conversely, the adaptive model permits participants to be corrupted at any point during the protocol, maintaining their corrupted status until completion. The proactive security model parallels the adaptive model; however, it allows participants who become corrupt to revert to honesty over time, mimicking real-world situations where compromised systems can purge adversaries and regain their honest status after detecting malicious activities.

Concerning the proportion of corrupt participants as discussed in [18], it is typically assumed there is either a majority of honest or dishonest participants. In scenarios with a majority of honest individuals, the security of the protocol is maintained as long as the majority remain truthful. Conversely, for a dishonest majority, the protocol remains secure even when most participants are compromised. In most cases, protocols must balance between security and performance as highlighted in [16]. For instance, ensuring security against a malicious adversary is typically more challenging than protecting against a semi-honest adversary, which often results in increased computational demands.

2.3.2. Use Cases

First introduced by Andrew Yao in the 1980s [22], SMPC primarily focused on theoretical development and feasibility in its first twenty years. Nonetheless, since the turn of the millennium, there has been a steady rise in its practical applications.

A prominent early example of practical SMPC deployment was a secure auction for Danish sugar beet contracts, where a key requirement was to maintain the confidentiality of bids [23]. In 2008, Danish farmers and the Danisco company used a so-called double auction to negotiate production contracts. In this format, sellers and buyers each submit bids indicating the quantity of goods they are willing to trade at various predefined price points [24]. The auctioneer then calculates the equilibrium price, where aggregate demand equals aggregate supply. The farmers sought to keep their individual bids private to protect their position in future negotiations, which motivated the use of SMPC. The implementation relied on three separate servers to safeguard the data: one operated by Danisco, one by the farmers’ association, and a third by the research group that developed the protocol. Approximately 1200 farmers and the Danisco company submitted their bids via a web server [24]. Each submitted bid was then secret-shared and encrypted in a database using the servers’ public keys. Once all bids were collected, the servers jointly performed the computation. This system determined the market clearing price—the per-unit cost of the commodity—while ensuring the confidentiality of all individual bid details.

Another use case is statistical studies on sensitive data. In 2015, a study conducted in Estonia investigated potential relationships between delayed degree completion and employment while studying [25]. The research resorted to SMPC due to the requirement for confidential data, specifically tax records and level of education (high school, college, etc.), which are both sensitive and could not be disclosed as raw text. The study used the ShareMind platform [19,26]. During the initial stage, both parties engaged in data provision exchanged information through secret sharing with three other computational entities. Subsequently, the data underwent transformation to eliminate extraneous fields and was consolidated into a singular analytical table. Ultimately, the analysts engaged with the data through Rmind, a statistical instrument within the ShareMind ecosystem [27].

An additional illustration of SMPC comes from a research initiative in Boston aimed at assessing gender-based disparities in wages [28]. In this scenario, corporations provided their compensation data by anonymously disclosing salaries categorized by gender, ethnicity, and employment rank, ensuring complete confidentiality and privacy. Wage data were collected for over 166,000 employees across 114 different firms, which comprises approximately 14% of the workforce in the greater Boston region [28]. To facilitate this study, the researchers introduced a solution named Web-MPC, which utilizes a JavaScript library referred to as JavaScript Implementation of Federated Functionalities (JIFF) [29].

Cryptographic key management and protection represent a distinct application of SMPC through the use of threshold cryptography [20]. Threshold cryptography allows the functionality associated with a single secret key to be distributed among n participants. Each participant contributes an individual cryptographic key share, ensuring no single party has comprehensive knowledge of the secret key, thus eliminating the need for a trusted authority to allocate keys. A subset of t or more shares, known as the threshold, can collaboratively conduct cryptographic tasks, such as signing digital documents or decrypting data. An essential security attribute of this system is that the full secret key is not reconstructed on any single device at any time, reducing the risk of exposure from single points of failure. The scheme maintains security and functionality even if up to shares become compromised or lost.

The latest significant development pertains to secure machine learning. In this context, SMPC is employed during model training to ensure data confidentiality, effectively addressing privacy concerns. This is achieved through federated learning [30,31], an approach that permits model training in a decentralized fashion, thus retaining data on the local device. The local device employs secret sharing techniques to convey its trained model to a central server, enabling updates to the overarching central model. A relevant illustration is Gboard, Google’s virtual keyboard, employing a compact language model on mobile devices [32]. The model is locally trained by the user and subsequently sends updates to a server. The server consolidates these updates into a new, comprehensive model, which is then disseminated back to users, maintaining the iterative process.

2.4. Healthcare and Secure Multi-Party Computation

As stated earlier, technological advances have led to the digitization of medical records in the form of EHRs [33]. EHR enhance data accessibility, facilitating extensive clinical trials and boosting diagnostic precision. Despite these benefits, the broad implementation of EHRs presents challenges, including issues related to access control, interoperability, and defense against cyber threats. As observed in [33], patient’s concerns over privacy, confidentiality, and security can lead to the withholding of relevant information, which can impact the quality of medical care. These concerns can be mitigated by improving technological literacy and increasing transparency. According to Nowrozy et al., the implementation of access control mechanisms, blockchain technologies, cloud computing, and cryptography is prevalent in the context of EHR data exchange [10]. In particular, blockchain technology can be leveraged to enhance privacy and grant patients greater control by transferring the ownership of medical records to the patients themselves. This approach facilitates a patient-managed, interoperable framework equipped with audit trails to monitor data access [10,33].

The FHIR standard is extensively acknowledged for resolving interoperability challenges in healthcare data exchange, facilitating quicker data transmission among entities [34]. This standard covers a broad spectrum, ranging from electronic health records (EHRs) to information from administrative and clinical studies. At its core, FHIR utilizes resources to act as abstract representations of different elements like diagnostic findings, patient records, medications, or medical procedures. These resources can be combined to create complex data systems such as EHRs. The data is structured using established formats like JSON or XML and is accessible through RESTful API interfaces.

Electronic Health Records naturally incorporate details that can be utilized to identify an individual, known as PII. Removing these identifiers alone often fails to fully anonymize the data. Within the European Union, the exchange of EHRs among distinct entities is subject to the stipulations of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). According to GDPR [35], data must be collected only if it is sufficient and absolutely necessary (data minimization) and is collected for a defined, explicit purpose (purpose limitation). Moreover, processing of this data requires the clear consent of the individual to whom it pertains, who also possesses the right to request its deletion (right to be forgotten). The GDPR distinguishes between data that is anonymous, which cannot be traced back to individuals, and pseudonymous data. Pseudonymous data pertains to personal information that cannot be associated with a specific individual unless additional data is used, provided this supplementary data is kept separately [36]. Within the framework of SMPC, the distinction between whether each share is categorized as anonymous or personal data remains unclear [37,38]. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that, when implemented correctly, no individual participant is able to access private information. Furthermore, the privacy implications of the particular computations being executed must be taken into account.

2.5. Comparison of SMPC with Other Privacy-Enhancing Technologies

SMPC enables distributed computation across multiple parties while preserving privacy, but alternative privacy-enhancing technologies offer complementary or competing approaches to similar problems. This section compares SMPC with two important related technologies: homomorphic encryption (HE) and coded computation, examining their fundamental differences, advantages, limitations, and suitability for different application scenarios.

2.5.1. Comparison of SMPC with Homomorphic Encryption

HE and SMPC represent distinct paradigms for privacy-preserving computation. HE allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without requiring decryption, enabling a single untrusted server to compute functions on encrypted data and return encrypted results that only the data owner can decrypt [39]. In contrast, SMPC distributes the computation across multiple parties who jointly evaluate a function over their combined private inputs, with none of them individually learning the inputs of others. This approach represents the fundamental difference between SMPC and HE. While HE can operate under a single-server model where an external party (such as a cloud service provider) performs computations on ciphertexts, SMPC, by comparison, requires active participation from multiple computing parties; it functions as a distributed protocol where each party maintains secret shares of data and actively participates in the computation.

Another critical distinction lies in computational overhead. SMPC operations, particularly in fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), are computationally expensive [40]. The cost of homomorphic operations typically far exceeds standard operations, resulting in significant slowdowns [41]. SMPC protocols, while still introducing overhead, often perform more efficiently for practical computations, especially for linear operations and protocols using additive secret sharing. The communication complexity of SMPC can be higher than HE in some scenarios, as SMPC often requires interaction between parties, whereas HE allows a single-pass computation model.

2.5.2. Comparison of SMPC with Coded Computations

Coded computation represents a recently emerging approach that combines coding theory with secure computation, particularly through techniques like Lagrange Coded Computing (LCC) [42]. Rather than explicitly using cryptography to mask data or split it into shares, coded computation encodes data using error-correcting codes in a manner that enables both privacy and security during distributed computation. It applies polynomial coding techniques to general computation problems. In the LCC approach, data is encoded as evaluations of a polynomial at different points, and these encoded pieces are distributed to workers [42]. Each worker performs the same computation on its encoded data, and the results can be combined using polynomial interpolation to recover the final result. This encoding structure simultaneously provides privacy (workers cannot individually recover the original data from their encoded pieces) and security (the computation remains correct even if some workers return incorrect results or fail).

A major advantage of coded computation is improved communication and storage efficiency compared to standard SMPC protocols [43]. Since coded computation leverages polynomial properties, it can achieve optimal tradeoffs between privacy level and security level while requiring minimal redundancy. The technique is universal in that multiple polynomial computations up to a certain degree can be computed on the same encoding, reducing the need for reencoding between different operations.

Coded computation excels particularly for polynomial computations and certain structured computation patterns [43]. While coded computation can theoretically address general polynomial functions up to a specified degree, SMPC provides greater generality for arbitrary computation patterns. SMPC has well-established protocols for any computable function, whereas coded computation is most efficient when computations naturally align with polynomial structures [42].

2.5.3. Comparative Analysis

SMPC, HE, and coded computation represent three complementary approaches to privacy-preserving distributed computation, each with distinct strengths and trade-offs. SMPC provides practical, theoretically grounded solutions for multiparty computation with minimal overhead for general computations. Homomorphic encryption is optimal for outsourced computation to untrusted servers but faces computational challenges. Coded computation offers innovations for large-scale distributed systems performing structured computations, combining privacy with inherent fault tolerance. The choice among these technologies should be guided by specific application requirements, including the threat model, scale of deployment, types of computations required, and the relative importance of communication efficiency, computational efficiency, and implementation maturity. Table 1 summarizes the feature comparison between SMPC, HE and Coded Computation.

Table 1.

Feature comparison between SMPC, HE and Coded Computation.

3. Proposed Solution

This section outlines our proposed architecture [44] and the creation of a proof-of-concept designed to examine the viability of employing SMPC for assembling clinical trial cohorts with confidential patient data.

3.1. Architecture

The proof-of-concept for creating clinical trials cohorts was designed to encompass three distinct entities: (i) the patient who owns their medical data; (ii) the clinical researcher; and (iii) the provider of the decentralized health platform.

The process initiates with the clinical investigator delineating the target patient profile for the study through the formulation of a set of selection criteria. Following this, the patient selects their medical data in accordance with these criteria, divides it into portions, and shares them with other participants. These three participants jointly review the criteria by examining the patient’s data. When there is a match, the patient is informed and asked about their interest in participating in the study. If the patient agrees, they provide their contact details to the clinical researcher. Patient confidentiality is maintained as unauthorized parties do not gain access to the entire dataset. This procedure is illustrated in Figure 5. The actual confidential storage of patient data is outside the scope of this study. We assume that the cryptographic keys that ensure that confidenciality are tied to the patient blockchain wallet. Under our architecture some mechanism, in principle a smart contract working under the control of the patient wallet, can retrieve medical data and create the secret shares in a scope accessible only to each patient. The SMPC approach insures that each computation participant cannot derive the original data from the secret shares that the participant receives.

Figure 5.

Flowchart representing the process.

3.2. Implementation

Our implementation incorporated Python v3.12 together with the open-source library MPyC [45], which employs Shamir’s secret sharing scheme [17]. This library ensures security assuming a majority of parties are honest, defending specifically against semi-honest adversaries. Its asynchronous evaluation capability enhances efficiency by enabling communication and computation to proceed simultaneously. MPyC’s use of Python’s operator overloading feature allows for rapid prototyping and development of SMPC concepts, making it accessible even to those without specialized SMPC expertise.

3.2.1. Selection Criteria Set

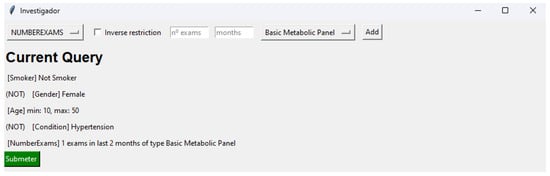

We constructed a simple graphical interface utilizing Python’s Tkinter (https://docs.python.org/3/library/tkinter.html, accessed on 25 July 2025), incorporating five categories for clinical researchers to define the selection criteria. This interface allows to select the following criteria: smoking status, gender, age range, SNOMED CT (https://www.snomed.org/, accessed on 25 July 2025) code, as well as the quantity and classifications of medical examinations that the patient has undergone in the preceding x months. Regarding the smoking status, the system interface maps non-smoker, current smoker, former smoker, and unknown to the respective numerical identifiers 0, 1, 2, and 3. In gender classification, four categories are available: male, female, other, and unknown, with these identifiers assigned numerical values from 0 to 3. For age, the clinical researcher defines an age range with minimum and maximum values. The interval is exclusive, meaning that the minimum and maximum ages are not included.

For the SNOMED CT, the prototype supports the four predefined conditions, identified through the respective code: Polyp of colon (68496003); Cardiac Arrest (410429000); Hypertension (59621000); and Hyperlipidemia (55822004). Finally, the researcher defines the minimum number of exams of a given type, that the patient has realized. Exam types are defined through the Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) (https://loinc.org/, accessed on 23 May 2025), which is a standard for identifying and describing exams, clinical, and laboratory results. The prototype supports four types of exams: Lipid panel (57698-3), Blood panel (58410-2), Basic Metabolic Panel (51990-0) and comprehensive metabolic panel (24323-8). To allows for an easier secret share, we dropped the hyphen and the last digit, yielding the codes 57698, 58410, 51990, and 24323.

Moreover, for every selection criterion, the inverse condition can also be employed. For instance, when clinical researchers choose the criterion of “male” gender and then apply the inverse condition, the selection will encompass all genders other than male. After finalizing and submitting the desired selection criteria, a JSON file is created, documenting the configuration of these selections. Listing 1 demonstrates the JSON file generated based on the selection criteria depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Interface representing each selected selection criteria.

| Listing 1. Example of a query.json file representing each selected selection criteria. |

| { |

| "params": [ "Smoker", "Gender", "Age", "Conditions", "NumberExams" ], |

| "restrictions": [ |

| { |

| "restriction_type": "SMOKER", |

| "value": 0, |

| "inverse": false |

| }, |

| { |

| "restriction_type": "GENDER", |

| "value": 0, |

| "inverse": true |

| }, |

| { |

| "restriction_type": "AGE", |

| "max_age": 24, |

| "min_age": 12, |

| "inverse": false |

| }, |

| { |

| "restriction_type": "CONDITION", |

| "value": 5582004, |

| "inverse": false |

| }, |

| { |

| "restriction_type": "NUMBEREXAMS", |

| "nr_exams": 2, |

| "type": 57698, |

| "nr_months": 200, |

| "inverse": false |

| } |

| ] |

| } |

3.2.2. Algorithm

In our experimental setup, we utilized a standardized program across all entities, with each participant’s role being determined by their assigned Patient IDentifier (PID). Specifically, we designated pid 0 for the patient, pid 1 for the clinical researcher, and pid 2 for decentralized healthcare platform. For the secure exchange of data, MPyC employs specialized secure types, and our investigation was centered on secure integers and secure arrays of integers. Algorithm 2 details the steps of the SMPC process. The procedure begins with the extraction of data, which is converted into a secure format. This secure data is then secret-shared among the other two participants. In the final step, we loop through each selection criterion, appraise these based on patient data, and verify whether all assessments result in a positive outcome.

| Algorithm 2 Algorithm of the proposed SMPC solution. |

|

3.2.3. Obtaining Data from FHIR Files

For the extraction phase, we utilized the JSON FHIR R4 dataset from Synthea (https://synthetichealth.github.io/synthea/, accessed on 29 April 2025), an open-source, synthetic patient generator that models the medical history of synthetic patients. Each file within this dataset contains comprehensive data of a patient, encompassing medical examinations, personal information, and health conditions. Using the JMESPath (https://jmespath.org/, accessed on 29 April 2025) library to query the JSON dataset, we acquired all the necessary information to verify the truthfulness of the selection criteria.

For determining age, we located the resource denoted as Patient and retrieved the birthDate attribute, from which the individual’s age is calculated. In terms of gender, we accessed the gender attribute of the Patient data, converting it to a range of values from 0 to 3.

To determine the smoking status, we investigated all resources categorized as Observation and identified by the LOINC code 72166-2, which denotes tobacco smoking status. We then sorted these observations by date to retrieve the latest data and captured the corresponding code. These codes can be 266919005 for a patient who has never smoked, 449868002 for daily smokers, and 8517006 for former smokers. We subsequently mapped these values to a scale of 0 to 3, with the value 3 indicating an unknown smoking status. Listing 2 shows the Python code that handles this extraction logic.

Under the given circumstances, we determined all resources classified as Condition where the clinicalStatus was active, and the verificationStatus was confirmed, and then retrieved their associated SNOMED CT codes. To gather all examinations along with their respective dates, we first identified the resources marked as DiagnosticReport, from which we extracted the LOINC code representing the exam type and the date utilizing the effectiveDateTime attribute.

To ensure the secure distribution of data among participants, we employed the MPyC method input(x) from the SecureObject class. Here, the parameter x is characterized as a secure object, specifically a secure integer (SecInt), since our proof-of-concept relied on utilizing integers as inputs. This function converts a private value into a shared secret object. Conversely, the MPyC method output(y) from the class SecureObject collects these individual shares, allowing for the reconstruction of the secret referenced by y.

| Listing 2. Python class for extracting the tobacco smoking status from a FHIR document. |

| from mpyc.runtime import mpc |

| from mpyc.sectypes import SecInt |

| import jmespath as jm |

| secint_32 = SecInt(32) |

| class ParamSmoker: |

| def __init__(self, value): |

| self.value = value |

| def secret_share(self): |

| return mpc.input(secint_32(self.value), senders=0) |

| # Creates a new ParamSmoker object from a FHIR document |

| # (in JSON format) passed in the ’data’ parameter. |

| @staticmethod |

| def from_fhir(data): |

| # Gets all Observations that have the code 72166-2 |

| # (Tobacco smoking status NHIS), sorted by most recent. |

| smoker = jm.search( |

| """entry[?resource.resourceType == ’Observation’ && |

| resource.code.coding[0].code == ’72166-2’] | |

| sort_by(@, &resource.issued)[-1].resource.valueCodeableConcept.coding[0].code""" |

| , data) |

| if smoker == ’266919005’: # never smoked tobacco |

| smoker = 0 |

| elif smoker == ’449868002’: # smokes tobacco daily |

| smoker = 1 |

| elif smoker == ’8517006’: # ex-smoker |

| smoker = 2 |

| else: # unknown |

| smoker = 3 |

| return ParamSmoker(smoker) |

3.2.4. Evaluation

To evaluate the selection criteria concerning patient data, we devised a unique function tailored to each criterion type. When the inverse parameter was activated, we calculated one minus the result (i.e., ), using the secure subtraction method sub(a,b).

To evaluate criteria concerning smoking status and gender, we ensured the patient data met the criteria by using the method eq(a,b) for secure value comparison. The patient’s age is determined using the function lt(a,b), which securely checks whether a is less than b. First, we confirm lt(min_age, age) and lt(age, max_age), and subsequently employ the secure method all() to validate if both conditions are true. Listing 3 shows the Python code that handles the evaluation of the smoking status restriction.

Initially, we examined each condition and matched it with the selection criteria using the eq(a,b) secure method. The results were organized into an array. Subsequently, we used the any() secure method to check for an element with the value 1, which signifies a true boolean value.

The process of assessing the criteria for selecting exams begins by iterating over the entire list of exams to identify the specific exam and tallying the exams conducted in the preceding x months. Subsequently, this count is compared against the number of specified exams. The summation is executed using the secure function sum(a,b), and comparisons are accomplished through the lt(a,b) and eq(a,b) methods.

| Listing 3. Python class for evaluating the smoking status restriction. |

| from mpyc.runtime import mpc |

| from mpyc.sectypes import SecInt |

| secint_32 = SecInt(32) |

| class RestrictionSmoker: |

| param = "Smoker" |

| def __init__(self, value: int, inverse: bool): |

| if value not in [0, 1, 2, 3]: |

| raise Exception("Value must be between 0 and 3") |

| self.restriction_type = "SMOKER" |

| self.value = value |

| self.inverse = inverse |

| def __eq__(self, other): |

| return (self.restriction_type == other.restriction_type and |

| self.value == other.value) |

| # Evaluates the smoking status restriction. |

| @mpc.coroutine |

| async def evaluate(self, smoker): |

| if self.inverse: |

| return mpc.sub(secint_32(1), mpc.eq(self.value, smoker)) |

| else: |

| return mpc.eq(self.value, smoker) |

3.2.5. Aggregation Tool

To simulate the computation for all three participants, it is necessary to run the Python script thrice in an asynchronous manner. As a result, we crafted an aggregation script that initiates and runs them using Python’s asyncio library, specifically through the create_subprocess_shell() function. Following this, the results of all three executions are aggregated using the gather(*obj) method, which assembles separate secure objects from each party into a unified list of secure objects. Finally, the application displays the patient’s FHIR file, indicating whether it satisfies the criteria necessary for inclusion in the cohort study.

The typical execution of the aggregation script aggregator.py involves performing a single run for a randomly selected patient, based on the selection criteria specified in the query.json file. This default configuration can be modified by specifying the population size, the specific FHIR file for a patient, and the related file that includes the selection criteria. Table 2 lists the command line parameters for the aggregator.py Python script.

Table 2.

List of all command line parameters available in the Python aggregator.py script.

4. Results

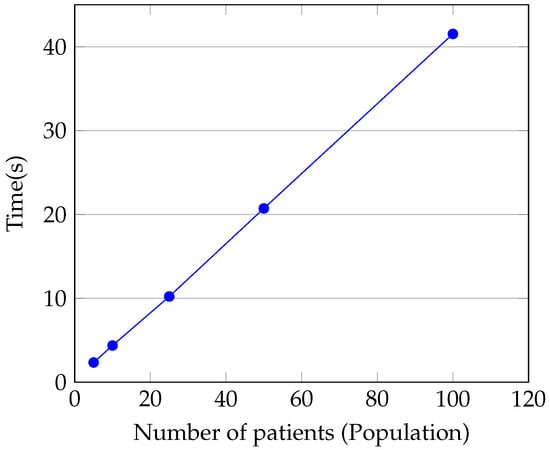

To evaluate our proof-of-concept, we collected data utilizing the Python time module, specifically the perf_counter() function, along with the default MPyC logging messages. The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11/23H2 machine equipped with an AMD Ryzen 5 5600 CPU and 8 GiB of RAM. It is important to note that communication time was excluded from our analysis, although it should be addressed in a practical implementation for a fairer assessment.

Figure 7 illustrates how the patient count (referred to as the population) correlates with the total execution duration. This dataset was derived by running the aggregator script 30 times and computing the average duration for patient groups of 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100. For our selection criteria, we chose one criterion from each category, and patients were drawn randomly a single time. As depicted, the execution time scales linearly with the population size, consuming approximately seconds per patient to determine their eligibility for inclusion in clinical trial cohorts.

Figure 7.

Relationship between execution time and number of patients.

Figure 7 illustrates a linear increase in execution time relative to population size. Consequently, subsequent experiments were carried out solely with 100 patients.

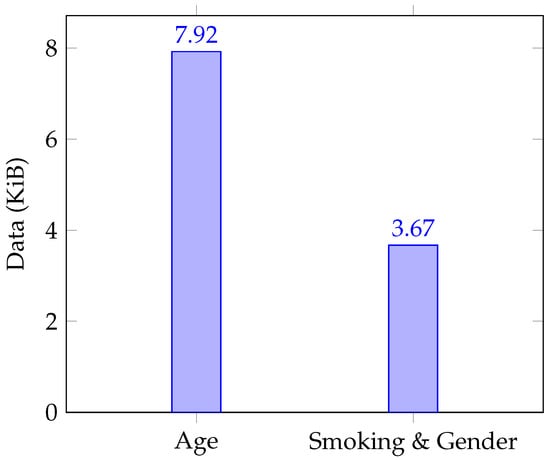

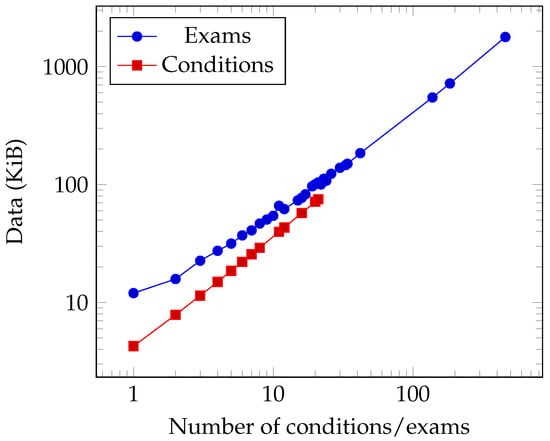

Figure 8 illustrates the data volume exchanged among participant types for both Age and Smoking\&Gender, while Figure 9 depicts this information for exams/conditions. The figures are based on the average bytes exchanged between participants over 30 distinct trials.

Figure 8.

Data sent for age, smoking and gender selection criteria.

Figure 9.

Data sent for a different number of conditions and exams.

The dataset employed for evaluating criteria regarding age, smoking habits, and gender selection follows a systematic pattern; individual comparisons are made for smoking and gender, while two comparisons are applied to age. Concerning medical conditions and examinations, data transmission scales in direct relation to the quantity of information analyzed. For example, when assessing a patient subjected to 459 examinations, the data exchanged amounted to 1780 KiB.

5. Discussion

This research illustrated the viability of using Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) for forming clinical trial cohorts using sensitive patient information, yielding a solution balancing between data usefulness and personal privacy. Results suggest that incorporating SMPC into a healthcare data framework can streamline data collection processes, such as cohort selection, minimizing time delays and reducing the volume of managed data shares. This removes one of the most relevant obstacle of private data sharing for cohort study, offering a solution for clinical researchers to access and analyze aggregated patient characteristics without compromising the confidentiality of individual records. The charactistics, in terms of confidenciality and privacy, that our proposed solution provides aligns with the current guidelines in the European Health Data Space [46] by providing a confidential (no single node in the computation can obtain the patient data) and privacy preserving (the computation results don’t allow for the inferences on the original data) mechanism for secondary uses.

Selecting MPyC for the SMPC implementation, along with Python and FHIR-based data structures, enabled secure integer operations and array processing, demonstrating the viability of using contemporary SMPC libraries in healthcare contexts. The capability to execute computations on private data, ensuring that no single participant uncovers the inputs from others, is crucial for data sharing in sensitive areas. Section 4 examined specific characteristics of the proof-of-concept, including the short time interval needed to assess the eligibility of an individual for inclusion in the clinical trial cohort. This evaluation process can be expedited further by opting for an alternative implementation of SMPC, such as employing a C/C++ version instead of relying on a Python implementation, which is documented to be significantly slower [47]. Evaluating the optimal cost-benefit security model with precision is essential prior to implementation. The MP-SPDZ [47] framework offers a method to comprehensively analyze the balance between costs and benefits, enhancing decision-making.

One of the limitations of our proof-of-concept is its dependence on predefined selection criteria. Establishing new criteria necessitates outlining the method for extracting pertinent information from the FHIR file, determining a suitable data type for sharing, and designing a process to assess the new criteria. Another limitation is that only specific data types can be shared and evaluated, often necessitating the use of particular formats and standards, like LOINC and SNOMED CT, for representing medical conditions, diagnostic tests, and clinical findings. These formats also pose challenges; for example, if a condition is novel, uncommon, or absent from these coding systems, it cannot be feasibly chosen as a condition for the selection criteria. Furthermore, while the time overhead was minimal for the tested scenarios, scalability remains a critical consideration for significantly larger datasets or a greater number of participating institutions, where the communication and computational burdens of SMPC protocols can escalate.

A proof-of-concept study inherently omits several legitimate concerns from its scope. The question is can this method be successfully implemented in real-world scenarios, where conditions are not completely controllable? We acknowledge that implementing a solution using our suggested method will encounter challenges, but these should be assessed against other methods and their associated complexities. The primary alternative to forming a clinical trial cohort without breaching patient confidentiality is encryption, which comes with significant drawbacks such as key management and computational complexity, particularly with techniques like Homomorphic Encryption. The efforts to implement a SMPC approach appear advantageous when compared to the complexity involved in cryptographic solutions, especially considering that quantum computing might soon pose a real concern.

6. Conclusions

The study explored the viability of employing Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) for constructing clinical trial cohorts from patients’ confidential data. It tackled the challenge of balancing data-driven research needs with the critical importance of patient privacy and confidentiality. We devised and assessed a prototype system that involves three key participants—the patient, the clinical researcher, and a computation service provider—who collaboratively assess a patient’s trial eligibility without exposing raw medical data to unauthorized parties. This system utilizes the MPyC library to execute secure computations on data derived from standard FHIR files, evaluating it against predefined criteria such as age, gender, smoking habits, and particular medical conditions and tests.

Our results demonstrate that SMPC is a viable solution for this use case. The proof-of-concept exhibited efficient performance, with execution time scaling linearly with the number of patients, requiring only a minimal computational overhead per patient. This confirms that private cohort selection can be achieved without imposing significant delays. The architecture guarantees that no single entity gains access to the complete patient profile, thus preserving privacy throughout the eligibility assessment process. However, we also identified key constraints, notably the system’s reliance on predefined selection criteria and its dependency on standardized coding systems like SNOMED CT and LOINC, which could limit its applicability for novel or non-coded conditions.

In future research, multiple pathways can be explored to enhance the system’s adaptability and efficiency. An enhancement would involve crafting a more versatile framework that lets clinical researchers establish custom selection criteria via an intuitive interface, which would be automatically transformed into a circuit compatible with SMPC. This approach would address the current constraint of fixed criteria. Additionally, performance might be improved by transitioning the implementation from Python to a more rapid framework such as MP-SPDZ, supporting compiled languages like C/C++. This transition would also permit a comparative study of various security models (e.g., semi-honest versus malicious) and their respective performance implications. Future endeavors should involve large-scale experiments that incorporate real-world network latency to thoroughly evaluate the system’s feasibility in a production context. On a higher level, subsequent research should include the integration of blockchain technology to incentivize patients to enter cohort studies by providing a means to regulate access and data sharing, coupled to a reward mechanism such as monetization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B., B.F. and R.G.; methodology, M.M., R.G., C.M.A. and V.T.; software, R.B. and B.F.; validation, M.M., R.G., C.M.A. and V.T.; investigation, R.B. and B.F.; resources, M.D., R.C.B. and V.T.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.A. and P.D.; writing—review and editing, C.M.A. and P.D.; visualization, C.M.A. and P.D.; supervision, M.M., R.G., V.T., M.D. and R.C.B.; project administration, V.T.; funding acquisition, V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Project BlockchainPT—Decentralize Portugal with Blockchain Agenda, WP 2: Health and Wellbeing, 02/C05-i01.01/2022.PC644918095-00000033, funded by the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Program (PPR) (https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt/, accessed on 25 July 2025), The Portuguese Republic and The European Union (EU) under the framework of Next Generation EU Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/AgendaBlockchain-IPLeiria/CHIQ-SMPC-Data/, accessed on 25 July 2025.

Acknowledgments

This work is included in the Blockchain.pt project, part of Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan with the objective of spreading blockchain to various sectors and it was done in partnership with BioGHP (https://www.bioghp.com/, accessed on 25 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Manuel Dias and Ricardo Correia Bezerra were employed by the company BioGHP. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSAs | Data Sharing Agreements |

| EHR | Eletronic Health Records |

| FHE | Fully Homomorphic Encryption |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HE | Homomorphic Encryption |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LCC | Lagrange Coded Computing |

| LOINC | Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes |

| PID | Patient IDentifier |

| PII | Personally Identifiable Information |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| SMPC | Secure Multi-Party Computation |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

References

- Uslu, A.; Stausberg, J. Value of the Electronic Medical Record for Hospital Care: Update From the Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, F.; Prieto, J.T.; Julien, S.P. Electronic Health Records: Origination, Adoption, and Progression. In Public Health Informatics and Information Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C. Electronic Health Record Implementation in Europe in 2022|Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1421309/ehr-implementation-in-europe/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Yardi, S. Electronic Health Records Statistics and Facts (2025). 2025. Available online: https://media.market.us/electronic-health-records-statistics/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Dash, S.; Shakyawar, S.K.; Sharma, M.; Kaushik, S. Big data in healthcare: Management, analysis and future prospects. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, T.; Seifollahi, S.; Chan, J.; Zhang, X.; Aksakalli, V.; Hudson, I.; Verspoor, K.; Cavedon, L. The Secondary Use of Electronic Health Records for Data Mining: Data Characteristics and Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.; Denholm, R.; Hollings, S.; Cooper, J.; Ip, S.; Walker, V.; Denaxas, S.; Akbari, A.; Banerjee, A.; Whiteley, W.; et al. Linked electronic health records for research on a nationwide cohort of more than 54 million people in England: Data resource. BMJ 2021, 373, n826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggaard, T.; Reguant, R.; Jørgensen, I.F.; Haue, A.D.; Lademann, M.; Aguayo-Orozco, A.; Hjaltelin, J.X.; Jensen, A.B.; Banasik, K.; Brunak, S. Disease trajectory browser for exploring temporal, population-wide disease progression patterns in 7.2 million Danish patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Almqvist, C.; Bonamy, A.K.E.; Ljung, R.; Michaëlsson, K.; Neovius, M.; Stephansson, O.; Ye, W. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrozy, R.; Ahmed, K.; Kayes, A.S.M.; Wang, H.; McIntosh, T.R. Privacy Preservation of Electronic Health Records in the Modern Era: A Systematic Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A.; Almomani, I. Digitization of healthcare sector: A study on privacy and security concerns. ICT Express 2023, 9, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, M. The Application of Blockchain Technology in Securing Electronic Health Records Blockchain for Healthcare Data Security. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinakaran, D.; Ramani, R.; Edwin Raja, S.; Selvaraj, D. Enhancing security in electronic health records using an adaptive feature-centric polynomial data security model with blockchain integration. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGiffen, M. Introducing Always Encrypted with Enclaves. In Pro Encryption in SQL Server 2022: Provide the Highest Level of Protection for Your Data; McGiffen, M., Ed.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Maximiano, M.; Gomes, R.; Távora, V.; Dias, M.; Bezerra, R.C. Architecture for Health Private Data Sharing using Blockchain. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Kolesnikov, V.; Rosulek, M. A Pragmatic Introduction to Secure Multi-Party Computation. Found. Trends® Priv. Secur. 2018, 2, 70–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, A. How to share a secret. Commun. ACM 1979, 22, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgård, I.; Pastro, V.; Smart, N.; Zakarias, S. Multiparty Computation from Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2012, Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2012, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2012; Safavi-Naini, R., Canetti, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, D. Sharemind: Programmable Secure Computations with Practical Applicationss. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, Y. Secure multiparty computation. Commun. ACM 2020, 64, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Or, M.; Goldwasser, S.; Wigderson, A. Completeness theorems for non-cryptographic fault-tolerant distributed computation. In Providing Sound Foundations for Cryptography: On the Work of Shafi Goldwasser and Silvio Micali; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, A.C. Protocols for secure computations. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1982), Chicago, IL, USA, 3–5 November 1982; pp. 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetoft, P.; Christensen, D.L.; Damgård, I.; Geisler, M.; Jakobsen, T.; Krøigaard, M.; Nielsen, J.D.; Nielsen, J.B.; Nielsen, K.; Pagter, J.; et al. Secure multiparty computation goes live. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Accra Beach, Barbados, 23–26 February 2009; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Talviste, R. Applying Secure Multi-Party Computation in Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tartu, Estonia, Tartu, Estonia, 2016. Supervised by Sven Laur and Dan Bogdanov. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, D.; Kamm, L.; Kubo, B.; Rebane, R.; Sokk, V.; Talviste, R. Students and taxes: A privacy-preserving study using secure computation. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2016, 2016, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, D.; Laur, S.; Willemson, J. Sharemind: A framework for fast privacy-preserving computations. In Proceedings of the Computer Security-ESORICS 2008: 13th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, MáLaga, Spain, 6–8 October 2008; Proceedings 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, D.; Kamm, L.; Laur, S.; Sokk, V. Rmind: A Tool for Cryptographically Secure Statistical Analysis. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2018, 15, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapets, A.; Jansen, F.; Albab, K.D.; Issa, R.; Qin, L.; Varia, M.; Bestavros, A. Accessible Privacy-Preserving Web-Based Data Analysis for Assessing and Addressing Economic Inequalities. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS ’18), New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiparty. GitHub—Multiparty/Jiff: JavaScript Library for Building Web-Based Applications That Employ Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC). Available online: https://github.com/multiparty/jiff (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Muazu, T.; Mao, Y.; Muhammad, A.U.; Ibrahim, M.; Kumshe, U.M.M.; Samuel, O. A federated learning system with data fusion for healthcare using multi-party computation and additive secret sharing. Comput. Commun. 2024, 216, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Dai, H.; Yang, G.; Xiang, Y. Robust Federated Learning for Privacy Preservation and Efficiency in Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2025, 18, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Andrew, G.; Choquette, C.; Kairouz, P.; Mcmahan, B.; Rosenstock, J.; Zhang, Y. Federated Learning of Gboard Language Models with Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 5: Industry Track), Toronto, ON, USA, 9–14 July 2023; Sitaram, S., Beigman Klebanov, B., Williams, J.D., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, N.N.; Ambe, S.; Ekhator, C.; Fonkem, E. Health Records Database and Inherent Security Concerns: A Review of the Literature. Cureus 2022, 14, e30168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorisek, C.N.; Lehne, M.; Klopfenstein, S.A.I.; Mayer, P.J.; Bartschke, A.; Haese, T.; Thun, S. Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) for Interoperability in Health Research: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e35724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—Official Legal Text—gdpr-info.eu. Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.J. Singling out people without knowing their names—Behavioural targeting, pseudonymous data, and the new Data Protection Regulation. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2016, 32, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.M.; Varia, M.; Cohen, A.; Sellars, A.; Bestavros, A. Multi-Regulation Computing: Examining the Legal and Policy Questions That Arise From Secure Multiparty Computation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Symposium on Computer Science and Law (CSLAW ’22), Washington, DC, USA, 1–2 November 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, G.; Schmechel, P. Personal data and encryption in the European general data protection regulation. J. Intellect. Prop. Inf. Technol. E-Commer. Law 2016, 7, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Munjal, K.; Bhatia, R. A systematic review of homomorphic encryption and its contributions in healthcare industry. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 9, 3759–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheibner, J.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. Health data privacy through homomorphic encryption and distributed ledger computing: An ethical-legal qualitative expert assessment study. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smajlović, H.; Shajii, A.; Berger, B.; Cho, H.; Numanagić, I. Sequre: A high-performance framework for secure multiparty computation enables biomedical data sharing. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kruglik, S.; Mao Kiah, H. Verifiable Coded Computation of Multiple Functions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 8009–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Raviv, N.; Avestimehr, A.S. Coding for Private and Secure Multiparty Computing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW), Guangzhou, China, 25–29 November 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.; Borges, R.; Antunes, C.M.; Maximiano, M.; Gomes, R.; Távora, V.; Dias, M.; Correia Bezerra, R. Can Secure MultiParty Computation Be Used to Create Clinical Trial Cohorts Based on Blockchain Notarized Private Patient Data? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, B. MPyC: Multiparty Computation in Python. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/lschoe/mpyc (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS)—Public Health; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Keller, M. MP-SPDZ: A Versatile Framework for Multi-Party Computation. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’20), Virtual Event, 9–13 November 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1575–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.