Digital Boundaries and Consent in the Metaverse: A Comparative Review of Privacy Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Data Collection in Metaverse

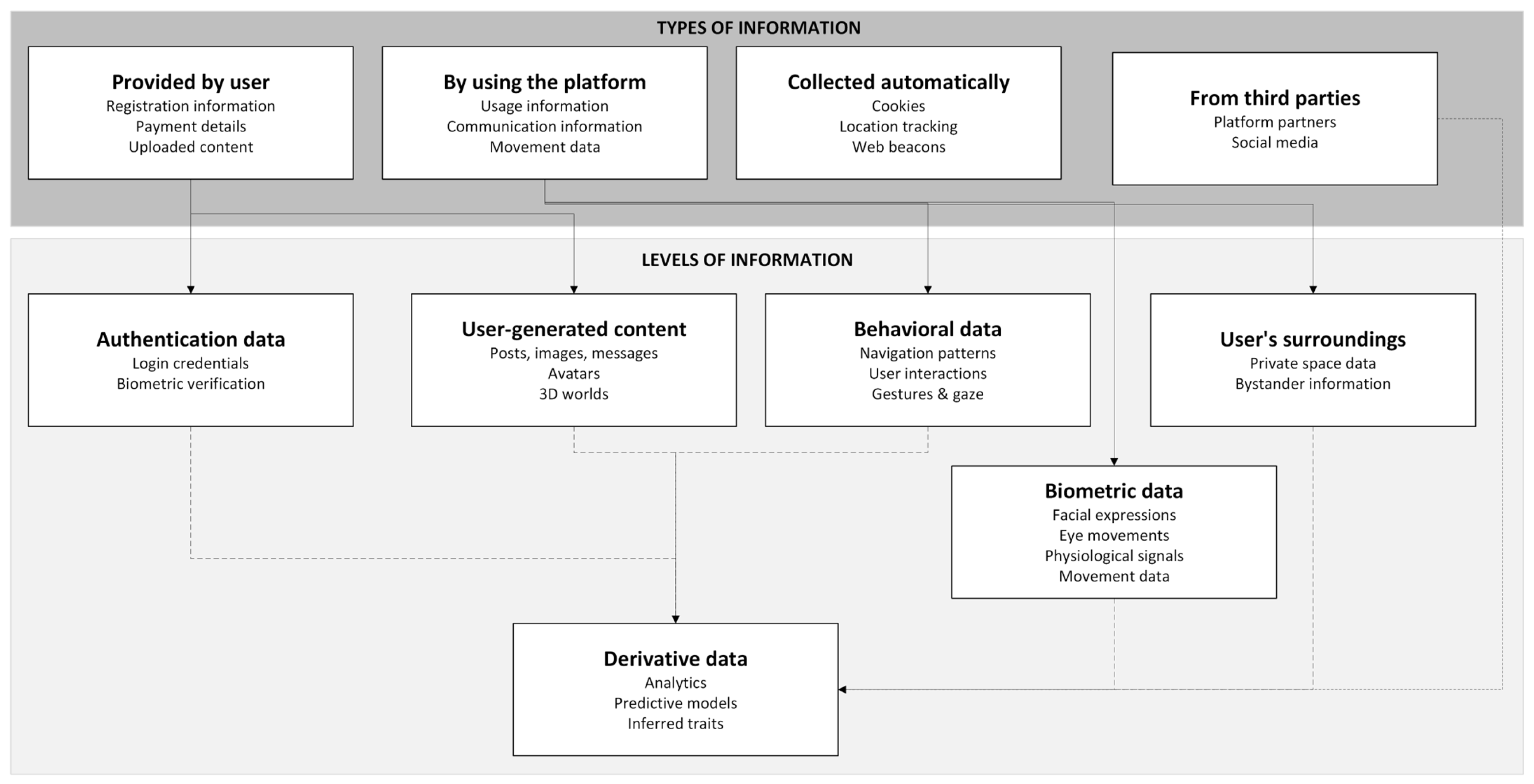

3.1. Types of Information in Metaverse Platforms

3.1.1. Information Provided by Users

- Registration and account information: This information could include username, password, email, birth date, and country of residence.

- Payment information: When the user buys a service or conducts transactions, the platform collects personal details like ID verification, date of birth, address, phone number, and payment information. Transaction details, such as amounts, parties, methods, and related circumstances (e.g., third-party accounts like PayPal), may also be retained.

- Uploaded content: Information and content provided in services available within the metaverse, like forums and community environments that do not have a restricted audience, is included.

3.1.2. Information by Using the Platform

- Usage Information: This information includes data such as IP address, browser type/version, visited pages, time spent, and unique device identifiers. Additional data may be sent by the user’s browser during visits.

- Communication Information: This information includes personal information that the user may share through microphone conversations, text chats, or other interactions and communication links between system components.

- Movement Data: When using a metaverse platform with devices such as a VR headset, it may gather biometric data on the physical movements of fingers, hands, head, and other body parts, depending on the equipment, to animate the avatar.

3.1.3. Data Collected Automatically

- Cookies: Utilized to recognize users across services, improve experience, enhance security, analyze trends, and personalize ads.

- Location Tracking: Many apps provide settings that allow users to limit or disable explicit location sharing; however, the availability and effectiveness of these controls vary across platforms. Additionally, some forms of location tracking, such as IP geolocation, cannot be disabled by users, meaning complete control over location data may be limited.

- Web Beacons: Utilized to track how the user interacts with the platform, tailor content, measure usability, and resolve technical issues.

3.1.4. Data Collected from Third Parties

- Platform Partners: A metaverse platform may receive personal information from third parties, such as analytics services, gaming platforms, social networks, and advertisers.

- Social Media: The platforms may use personal information from linked profiles, (e.g., Facebook).

3.2. Levels of Information in Metaverse Platforms

3.2.1. Authentication Data

3.2.2. User-Generated Content

3.2.3. Behavioral Data

3.2.4. Biometric Data

3.2.5. Derivative Data

3.2.6. User’s Surroundings Data

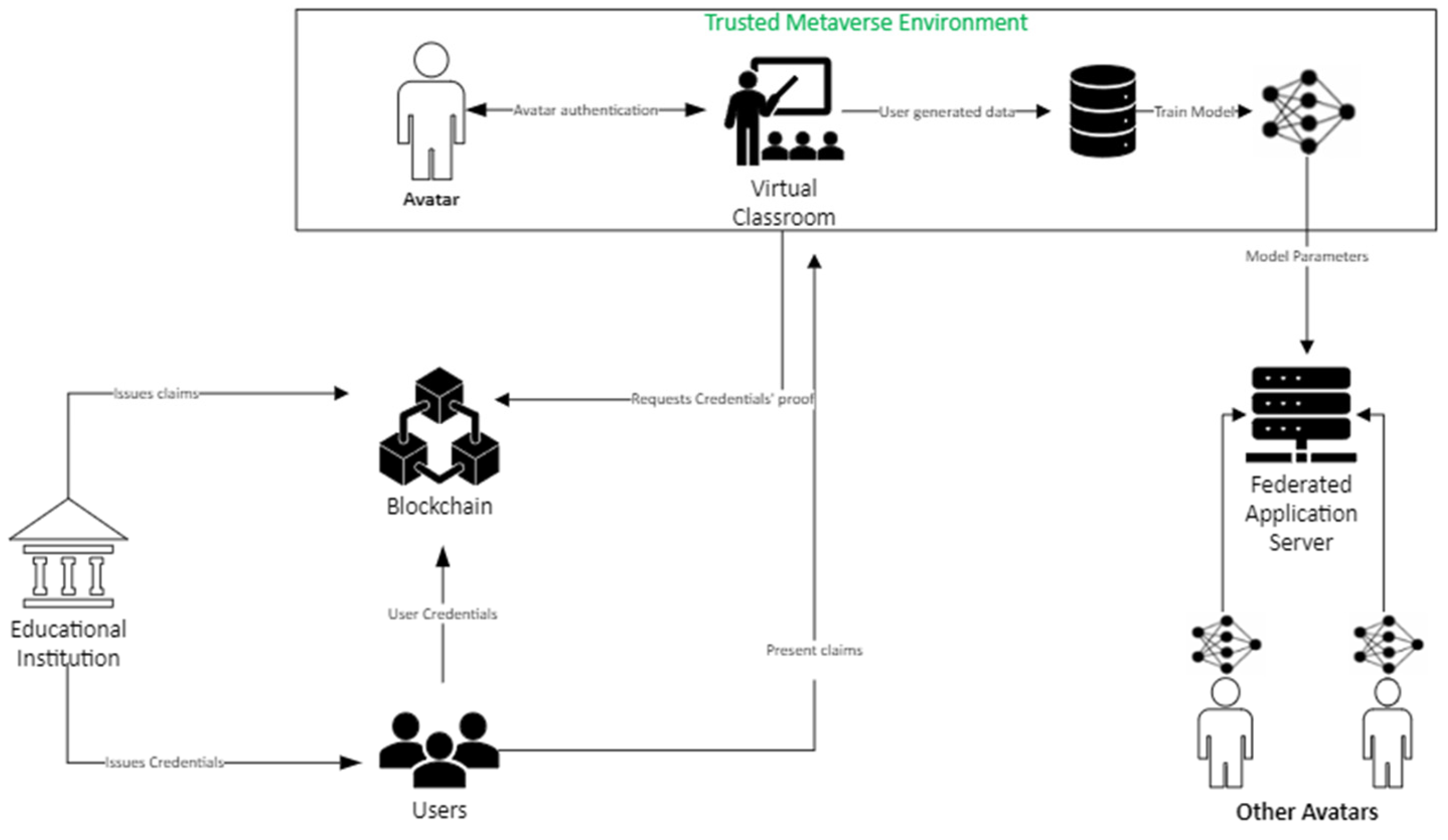

3.3. Data in Metaverse-Based Education

4. Security and Privacy Vulnerabilities of Metaverse’s Implemented Technologies

4.1. Existing Threats from the Perspective of the Identity Management Lifecycle

- Identity Theft and Impersonation: Serving as virtual representations of a user’s identity, avatars are susceptible to being duplicated or stolen, potentially resulting in impersonation. Furthermore, the impersonator could attempt to gather personal information, opening the door to social engineering or manipulation [44]. In educational environments, impersonation can grant unauthorized individuals access to virtual classrooms, where they may behave inappropriately, distract other students, and create safety concerns. Additionally, such actions can lead to fraudulent submissions of work, ultimately undermining academic integrity. The use of avatars to conceal one’s identity can be manipulated for fraudulent purposes, including scams, deepfakes, and deceitful transactions within the metaverse. Further, the anonymity afforded by avatars complicates the attribution of actions to real-world individuals, posing challenges for accountability and legal enforcement [51]. Anonymity becomes especially problematic in educational settings, where verifying the identity of students and educators is crucial for maintaining trust. Ensuring that individuals are who they claim to be is vital for creating a safe and effective learning environment.

- Psychological Manipulation and Harassment: Avatars can be created or utilized for deviant purposes, allowing for psychological manipulation or harassment of other users [52]. This behavior undermines students’ mental well-being and deters participation, particularly among those who are more vulnerable.

- Data Privacy Concerns: The creation and use of avatars often involve the collection of critical personal data, including biometric information like facial expressions and voice patterns. If not properly secured, this data can be vulnerable to unauthorized access or misuse, posing significant privacy risks [44]. In education, where students may be minors, the handling of such sensitive data becomes even more critical, necessitating strict compliance with privacy regulations and ethical standards.

4.2. Existing Threats in Data Lifecycle

4.3. Existing Threats from the Perspective of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

5. Consent in Selected Metaverse Platforms

5.1. VRChat

5.2. Oncyber

5.3. Sansar

5.4. SecondLife

5.5. Decentraland

6. Conceptualizing User Consent in Metaverse Environments

- Explicit consent: Explicit consent is a form of user consent that is clearly and unambiguously given, often through written statements. These statements include clicking the traditional “I Accept” button upon reviewing the terms and conditions, checking an empty box indicating agreement to receive marketing emails, or signing a document authorizing the use of personal health data for a designated research project.

- Implicit consent: With implicit consent a user has provided information (i.e., email, name) for various purposes, such as buying a product but has not explicitly agreed to the use of their data for something like marketing. With implicit consent, the user’s consent is assumed.

- Informed consent: As its name implies, the user is informed with the necessary information in order to decide whether to give their consent or not. Specifically, the user is informed about the type of data the company will process, how it will be used, and the purpose of each processing operation for which consent its required [31].

6.1. Tracking Technologies

- Accept All: grant consent for all data processing purposes to all third parties residing on the visited website.

- Reject All: deny consent for all data processing purposes to all third parties residing in the visited website.

- No Action: avoid interacting with the form in any way.

6.2. Bystander’s Consent

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mourtzis, D.; Panopoulos, N.; Angelopoulos, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, L. Human Centric Platforms for Personalized Value Creation in Metaverse. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Azzaoui, A.E.; Singh, S.K.; Salim, M.M.; Jeremiah, S.R.; Park, J.H. The Future of Metaverse: Security Issues, Requirements, and Solutions. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 12, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawki, M.; Basu, S.; Choi, K.-S. Redefining Boundaries in the Metaverse: Navigating the Challenges of Virtual Harm and User Safety. Laws 2024, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricomi, P.P.; Nenna, F.; Pajola, L.; Conti, M.; Gamberini, L. You Can’t Hide Behind Your Headset: User Profiling in Augmented and Virtual Reality. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9859–9875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchuk, B.; Loeb, S.; Neff, R. The Social Metaverse: Battle for Privacy. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2018, 37, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, R.; Cresci, S. Metaverse: Security and Privacy Issues. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 13 December 2021; pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sakka, S.; Liagkou, V.; Stylios, C.; Ferreira, A. On the Privacy and Security for E-Education Metaverse. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kos Island, Greece, 8 May 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hartina, S.; Nurcholis, M.; Dewi, A. Metaverse in Education: Exploring the Potential of Learning in Virtual Worlds. J. Pedagog. 2024, 1, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddoura, S.; Al Husseiny, F. The Rising Trend of Metaverse in Education: Challenges, Opportunities, and Ethical Considerations. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hwang, Y. Technology-Enhanced Education through VR-Making and Metaverse-Linking to Foster Teacher Readiness and Sustainable Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-Y. Cyber-Physical Metaverse Learning in Cultural Sustainable Education. Libr. Hi Tech 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukur, M.; Schneider, J.; Househ, M.; Dokoro, A.H.; Ismail, U.I.; Dawaki, M.; Agus, M. The Metaverse Digital Environments: A Scoping Review of the Challenges, Privacy and Security Issues. Front. Big Data 2023, 6, 1301812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, S.D.; Mithesh, G.S.S.; Panyam, R.; Chowdary, M.S.; Sadhu, V.S.; Sheela, J. Advancing Education through Metaverse: Components, Applications, Challenges, Case Studies and Open Issues. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), Coimbatore, India, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 880–889. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, W. Digital Identity, Privacy Security, and Their Legal Safeguards in the Metaverse. Secur. Saf. 2023, 2, 2023011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lan, R.; Hua, Z. Metaverse: Security and Privacy Concerns. J. Metaverse 2023, 3, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychronaki, M.; Xevgenis, M.G.; Kogias, D.G.; Leligou, H.C. Decentralized Identity Management for Metaverse-Enhanced Education: A Literature Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y. The Metaverse in Education: Definition, Framework, Features, Potential Applications, Challenges, and Future Research Topics. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1016300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Wan, S.; Gan, W.; Chen, J.; Chao, H.-C. Metaverse in Education: Vision, Opportunities, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 2857–2866. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos, A.; Mystakidis, S.; Pellas, N.; Laakso, M.-J. ARLEAN: An Augmented Reality Learning Analytics Ethical Framework. Computers 2021, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wang, H.; Qiao, D.; Xu, J.; Yan, T. Application of Zero-Watermarking Scheme Based on Swin Transformer for Securing the Metaverse Healthcare Data. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letafati, M.; Otoum, S. On the Privacy and Security for E-Health Services in the Metaverse: An Overview. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 150, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, N.; Xing, R.; Liu, D.; Luan, T.H.; Shen, X. A Survey on Metaverse: Fundamentals, Security, and Privacy. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbay, Y.; Utku, A.; Canbay, P. Privacy Concerns and Measures in Metaverse: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 15th International Conference on Information Security and Cryptography (ISCTURKEY), Ankara, Turkey, 19–20 October 2022; pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Iqbal, U.; Saxena, N. Opted Out, Yet Tracked: Are Regulations Enough to Protect Your Privacy? Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2024, 2024, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetrust. Available online: https://www.onetrust.com/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ruiu, P.; Nitti, M.; Pilloni, V.; Cadoni, M.; Grosso, E.; Fadda, M. Metaverse & Human Digital Twin: Digital Identity, Biometrics, and Privacy in the Future Virtual Worlds. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Munilla Garrido, G.; Song, D.; O’Brien, J. Exploring the Privacy Risks of Adversarial VR Game Design. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2023, 2023, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, K.; Hosfelt, D.; Chase, S.; Miesnieks, M.; Beck, T. The Ethical and Privacy Implications of Mixed Reality. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2019 Panels, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 28 July 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, R.; Ferreira, A.; Lepore, C.; Kandi, M.-A.; Sibilla, M.; Benzekri, A. The Interplay Between Policy and Technology in Metaverses: Towards Seamless Avatar Interoperability Using Self-Sovereign Identity. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom), Kyoto, Japan, 26–28 June 2023; pp. 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Zytko, D.; Chan, J. The Dating Metaverse: Why We Need to Design for Consent in Social VR. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 2489–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xynogalas, V.; Leiser (Mark), M.R. The Metaverse: Searching for Compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation. Int. Data Priv. Law 2024, 14, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—Legal Text. Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Basyoni, L.; Tabassum, A.; Shaban, K.; Elmahjub, E.; Halabi, O.; Qadir, J. Navigating Privacy Challenges in the Metaverse: A Comprehensive Examination of Current Technologies and Platforms. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2024, 7, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.C.; Munilla-Garrido, G.; Song, D. Going Incognito in the Metaverse: Achieving Theoretically Optimal Privacy-Usability Tradeoffs in VR. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, San Francisco, CA, USA, 29 October–1 November 2023; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rahartomo, A.; Merino, L.; Ghafari, M. Metaverse Security and Privacy Research: A Systematic Review. Comput. Secur. 2025, 157, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windl, M.; Laboda, P.Z.; Mayer, S. Designing Effective Consent Mechanisms for Spontaneous Interactions in Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Singh, P.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, A.; Hedabou, M. Privacy and Security in the Metaverse: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 120209–120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosio, G.; Obafemi, F. Augmented Accountability: Data Access in the Metaverse. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 59, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Khan, A.; Ali, A. The Impact of User-Generated Content, Social Interactions and Virtual Economies on Metaverse Environments. J. Sustain. Econ. 2023, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YemenïCï, A.D. Entrepreneurship in The World of Metaverse: Virtual or Real? J. Metaverse 2022, 2, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Cukurova, M.; Song, Y. Learning Analytics in Immersive Virtual Learning Environments: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, N.; Wang, M. The Impact of Interaction on Continuous Use in Online Learning Platforms: A Metaverse Perspective. Internet Res. 2024, 34, 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, G.M.; Nair, V.; Song, D. SoK: Data Privacy in Virtual Reality. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2024, 2024, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara, J.C.; Tasic, I.; Cano, M.-D. Enhancing Digital Identity: Evaluating Avatar Creation Tools and Privacy Challenges for the Metaverse. Information 2024, 15, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Evangelidis, G. Learning Analytics and Educational Data Mining in Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and the Metaverse: A Systematic Literature Review, Content Analysis, and Bibliometric Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.; Omar, A. The Ethical Dilemma of Educational Metaverse. Recent Adv. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2024, 1, 006–016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Gautam, D.; Kumar, P.; Das, A.K.; K., V.B.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Blockchain-Assisted Cross-Platform Authentication Protocol With Conditional Traceability for Metaverse Environment in Web 3.0. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 7244–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y. Design of Secure Mutual Authentication Scheme for Metaverse Environments Using Blockchain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 98944–98958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Kumar, P.; Chen, C.-M.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Anchna; Prajapat, S. A Robust Privacy-Preserving ECC-Based Three-Factor Authentication Scheme for Metaverse Environment. Comput. Commun. 2023, 211, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakk, Á.K.; Bényei, J.; Ballack, P.; Parente, F. Current Possibilities and Challenges of Using Metaverse-like Environments and Technologies in Education. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1521334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, B.C. Avatars in the Metaverse: Potential Legal Issues and Remedies. Int. Cybersecur. Law Rev. 2022, 3, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dennehy, D.; Metri, B.; Buhalis, D.; Cheung, C.M.K.; et al. Metaverse beyond the Hype: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Emerging Challenges, Opportunities, and Agenda for Research, Practice and Policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, T.; Matovu, R.; Serwadda, A.; Muirhead, N. Unsure How to Authenticate on Your VR Headset?: Come on, Use Your Head! In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Workshop on Security and Privacy Analytics, Tempe, AZ, USA, 21 March 2018; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Qamar, S.; Anwar, Z.; Afzal, M. A Systematic Threat Analysis and Defense Strategies for the Metaverse and Extended Reality Systems. Comput. Secur. 2023, 128, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Limniotis, K. Data Protection Issues in Automated Decision-Making Systems Based on Machine Learning: Research Challenges. Network 2024, 4, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosharraf, M. Data Governance in Metaverse: Addressing Security Threats and Countermeasures across the Data Lifecycle. Technol. Soc. 2025, 82, 102910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaz, F.; Sajjad, S.M.; Iqbal, Z.; Yousaf, M.; Muhammad, Z. MetaSSI: A Framework for Personal Data Protection, Enhanced Cybersecurity and Privacy in Metaverse Virtual Reality Platforms. Future Internet 2024, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Kang, G.; Kim, Y.-G. Security and Privacy in Big Data Life Cycle: A Survey and Open Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Pham, Q.-V.; Pham, X.-Q.; Nguyen, T.T.; Han, Z.; Kim, D.-S. Artificial Intelligence for the Metaverse: A Survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, A.; Eledlebi, K.; Zemerly, M.J.; Puthal, D.; Damiani, E.; Taha, K.; Kim, T.-Y.; Yoo, P.D.; Raymond Choo, K.-K.; Yim, M.-S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Cybersecurity for the Metaverse: Research Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 1008–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Xie, H.; Wah, B.W.; Gašević, D. Vision, Challenges, Roles and Research Issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Chien, S.-Y. Definition, Roles, and Potential Research Issues of the Metaverse in Education: An Artificial Intelligence Perspective. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaeed, M.; Qayyum, A.; Qadir, J. Privacy Preservation in Artificial Intelligence and Extended Reality (AI-XR) Metaverses: A Survey 2023. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 231, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busaidi, A.S.; Raman, R.; Hughes, L.; Albashrawi, M.A.; Malik, T.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Al- Alawi, T.; AlRizeiqi, M.; Davies, G.; Fenwick, M.; et al. Redefining Boundaries in Innovation and Knowledge Domains: Investigating the Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Copyright and Intellectual Property Rights. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbal, A.; Ali, M.K.; Abuzaraida, M.A. Artificial Intelligence Trust, Risk and Security Management (AI TRiSM): Frameworks, Applications, Challenges and Future Research Directions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240, 122442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Butt, M.A.; Ali, H.; Usman, M.; Halabi, O.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Imran, M.A.; Qadir, J. Secure and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence-Extended Reality (AI-XR) for Metaverses. ACM Comput Surv 2024, 56, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, B.; Yaşa Özeltürkay, E.; Gülmez, M. Metaverse Users’ Purchase Intention in Second Life. J. Metaverse 2024, 4, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadogiannakis, E.; Papadopoulos, P.; Kourtellis, N.; Markatos, E.P. User Tracking in the Post-Cookie Era: How Websites Bypass GDPR Consent to Track Users. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 2130–2141. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, T.; Childress, J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics: Marking Its Fortieth Anniversary. Am. J. Bioeth. AJOB 2019, 19, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadig, M.; Alohali, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.O.; Abulfaraj, A.W. Roles of Blockchain in the Metaverse: Concepts, Taxonomy, Recent Advances, Enabling Technologies, and Open Research Issues. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 38410–38435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Wang, W.; Yenduri, G.; Ranaweera, P.; Pham, Q.-V.; Da Costa, D.B.; Liyanage, M. Blockchain for the Metaverse: A Review. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 143, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyahrani, A. Non-Fungible Tokens, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations, Web 3.0, and the Metaverse in Education: From University to Metaversity. J. Educ. Learn. EduLearn 2023, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaeian Far, S.; Hosseini Bamakan, S.M. NFT-Based Identity Management in Metaverses: Challenges and Opportunities. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Yu, H.; Yang, Q. Threats to Federated Learning: A Survey 2020. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.02133. [Google Scholar]

- Geiping, J.; Bauermeister, H.; Dröge, H.; Moeller, M. Inverting Gradients—How Easy Is It to Break Privacy in Federated Learning? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.14053. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Ma, C.; Yang, H.H.; Farokhi, F.; Jin, S.; Quek, T.Q.S.; Vincent Poor, H. Federated Learning With Differential Privacy: Algorithms and Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 3454–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Mai, C.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Kang, J. Privacy Computing Meets Metaverse: Necessity, Taxonomy and Challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Naeem, F.; Kaddoum, G.; Hossain, E. Metaverse Communications, Networking, Security, and Applications: Research Issues, State-of-the-Art, and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 26, 1238–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, G.; López-Guzmán, J. Rethinking Privacy for Avatars: Biometric and Inferred Data in the Metaverse. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1520655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attack Type | Privilege Level | Affected Data Category | Attack Surface | Violated Security Goal(s) | Attacker’s Target | Potential Impact in Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen Smart Device | External | Authentication Data | Device | Confidentiality Authentication | Extract credentials-related parameters | Unauthorized access to student profiles or virtual classrooms |

| Offline Password Guessing | Passive Eavesdropper | Authentication Data | Device & Network | Confidentiality Authentication | Derive user password from intercepted and stored values | Account compromise, impersonation of educators/students |

| Impersonation | External | Authentication Data | Network | Authentication | Masquerade as a legitimate user | Infiltration of classes, manipulation of grades or discussions |

| Platform Server Spoofing | External | Authentication Data, UGC | Server | Integrity Authentication | Deceive users with a fake platform to steal data or credentials | Misdirection, phishing, or theft of sensitive learning data |

| Replay & MITM Attack | Passive/External | Authentication Data, Behavioral Data | Network | Integrity Authentication Non-Reputation | Reuse or intercept messages to bypass verification | Hijacked sessions, false submissions, altered attendance logs |

| Insider Attack | Internal | Behavioral Data, UGC | System/Avatar | Authentication Confidentiality | Abuse platform knowledge to impersonate others | Violation of academic integrity, avatar misuse |

| Privileged Insider Attack | Privileged Insider | Authentication Data, Derivative Data | System | Confidentiality Authentication | Use elevated access to steal or forge authentication data | Avatar impersonation, identity leakage |

| Ephemeral Secret Leakage | Advanced External | Authentication Data, Behavioral Data | Device/Network | Confidentiality Forward Secrecy | Use short and long term secrets to reconstruct secure sessions | Breach of session privacy, access to sensitive discussions |

| Perfect Forward Secrecy Breach | Advanced External | Behavioral Data, UGC | Session/Protocol | Forward Secrecy | Use long-term keys to decrypt past sessions | Retrospective access to private data, long-term privacy loss |

| User Anonymity Violation | Passive Eavesdropper | Behavioral Data, Derivative Data | Device & Network Protocol | Anonymity Privacy | Reveal true identity behind pseudonym | Student tracking, profiling, or targeting |

| Mutual Authentication Bypass | External/Internal | Authentication Data | Protocol | Authentication Integrity | Disrupt mutual trust between user and server | Unauthorized access, impersonation, unverified interactions |

| Threat Category | Data Lifecycle Phase | Affected Data Category | Description | Example Scenarios/ Attack Methods | Implications in Education | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Tampering | Storage, Sharing | Behavioral Data, Derivative Data, UGC | Unauthorized modification, deletion, or replacement of stored or in-transit data | Altered session logs, corrupted sensor data, fake class records | Undermines trust, misrepresents student behavior and participation | [6,22,54,56] |

| False Data Injection | Collection, Processing | Behavioral Data, Biometric Data, User’s Surroundings Data | Insertion of malicious data into XR systems or AI training models | Poisoned AI models, harmful haptic feedback (e.g., fake physical pain), falsified motion or environmental inputs | Harms physical safety, corrupts AI-driven recommendations and feedback systems | |

| Biometric & sensor data leakage | Collection, Storage | Biometric Data, Behavioral Data | Challenges in handling sensitive, biometric, or behavioral data captured via XR sensors | Eavesdropping, MITM, Man in the room, Packet Sniffing, Side-channel attack | High privacy risk, exposure of minors, biometric data theft | [22,54,56,57] |

| Low-Quality UGC & Sensor Input | Collection, Processing | UGC, Behavioral Data, Biometric Data | Poorly calibrated devices or unverified UGC lead to degraded experiences or flawed data models | Misaligned visuals, Νon-IID (non-independent and identically distributed) data in recommendation systems, erroneous inputs | Low quality of services and user experience, reduced immersion, poor recommendation quality | [22,56] |

| UGC Ownership & Provenance Issues | Storage, Sharing | UGC, Derivative Data | Difficulty verifying authorship and originality of user-generated content across distributed platforms | Remove embedded signatures or invisible watermarks that track original ownership, Copied educational content, replicated avatar-generated projects | Academic dishonesty, IP disputes, unfair attribution in collaborative environments | [22,54,57] |

| Intellectual Property Violations | Sharing, Destruction | UGC, Derivative Data | Inadequate legal and technical frameworks to enforce digital content rights | Use of recognizable individuals in avatar forms, unauthorized remixing of lecture content, reused AI-generated content | Legal ambiguity in digital content ownership and licensing in education | [22,54,56,57] |

| Insecure Data Retention/Destruction | Destruction | Biometric Data, UGC, Behavioral Data | Lack of proper mechanisms for data expiration, secure deletion, or revocation | Persistent biometric records post-course, inability to revoke user-generated data and content | Violates user consent, risk of future exposure, loss of “right to be forgotten” | [58] |

| Threat Category | Attacks | Description | Lifecycle Stage | Affected Data Category | Educational Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Integrity Attacks |

| Attackers corrupt training data or manipulate inputs to degrade model performance. | Training Inference | Behavioral Data, Biometric Data, Derivative Data | AI tutors give incorrect feedback, facial recognition login fails, learning manipulation |

| Federated Learning Exploits |

| Federated updates are manipulated to corrupt or extract private information. | Collaborative Training | Behavioral Data, Biometric Data, Derivative Data | Bias in shared education models, reduced personalization, data leakage |

| Behavioral Data Leakage |

| ML models leak user traits or behaviors from outputs or embeddings. | Data Collection Inference | Behavioral Data, Derivative Data | Inference of student mood, stress, or engagement; violation of privacy |

| Avatar and Identity Spoofing |

| AI-generated media impersonates users or teachers in XR. | Inference Interaction | Authentication Data, Biometric Data, UGC | Unauthorized exam participation, fake instructors spreading misinformation |

| Consent & Surveillance Risks |

| User data is collected without clear consent or beyond initial intent. | Data Collection | Biometric Data, Behavioral Data, User’s Surroundings Data | Trust erosion, collection of biometric data (gaze, voice) without student awareness |

| Behavioral Manipulation |

| AI agents influence users based on psychological patterns or reward signals. | Inference Interaction | Behavioral Data, Derivative Data | Student autonomy reduced, learning outcomes optimized for engagement, not understanding |

| Explainability Gaps |

| Users cannot understand why the AI behaves in certain ways. | Inference | Derivative Data | AI systems make opaque decisions (e.g., marking disengagement) without explanation |

| Ownership & Attribution Conflict |

| AI-generated or user-created educational assets are reused without attribution or consent. | Post-processing Deployment | UGC, Derivative Data | Students’ XR projects used in public apps, institutional IP disputes |

| Metaverse Platforms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collected | VRChat | OnCyber | Sansar | SecondLife | Decentraland | |

| By users | Registration and account | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Payment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | * | |

| Uploaded Content | ✓ | * | ✓ | * | * | |

| By platfrom | Usage | ✓ | ✓ | * | * | ✓ |

| Biometric | ✓ | × | * | * | × | |

| Movement | ✓ | × | * | * | × | |

| Surrounding | * | * | * | * | × | |

| Communication | ✓ | * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Aytomatically | Location Data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Device Data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| User preferences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | * | |

| Access Control | One-factor, optional two-factor | One-factor, wallet, via 3rd parties | One-factor, Mobile application | One-factor | Wallet, 3rd parties | |

| Compatibility | Desktop, VR | Desktop, VR | Desktop, VR | Desktop, VR | Desktop | |

| User Consent | explicit | explicit | explicit | explicit | implicit | |

| Bystander’s consent | × | × | × | × | × | |

| GDPR Principle/Article | Description | VRChat | Decentraland | SecondLife | Sansar | OnCyber | Sustainability Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Art. 5(1)(a) Lawfulness, Fairness, Transparency | Data collection must be lawful, fair, and transparent. | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | Builds long-term user trust, reduces misinformation and system misuse. |

| Art. 5(1)(e) Storage Limitation | Data must not be stored longer than necessary. | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Partial | Avoids unnecessary energy use in data storage, supports responsible digital resource use. |

| Art. 6 Lawfulness of Processing | Data processing must rely on a lawful basis, such as consent or contract. | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | Encourages ethical and lawful platform design, reducing legal/operational waste. |

| Art. 7 Conditions for Consent | Consent must be freely given, informed, specific, and unambiguous. | Lacking | Partial | Partial | Lacking | Partial | Empowers users, prevents misuse of personal data, supports ethical data ecosystems. |

| Art. 9 Special Category Data (e.g., biometrics) | Explicit consent is needed for biometric data processing. | Lacking | Not Applicable | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Prevents exploitation of sensitive data; reduces AI overreach, safeguards human dignity. |

| Art. 13/14 Right to Be Informed | Users must be told how and why their data is processed, including AI usage. | Partial | Lacking | Partial | Lacking | Lacking | Ensures transparency; encourages responsible data collection and usage. |

| Art. 15–17 Access, Rectification, and Erasure Rights | Users must be able to access, correct, or delete their data. | Partial | Partial | Partial | Lacking | Lacking | Supports data minimization and reduces unnecessary storage, empowers digital self-agency. |

| Art. 21 Right to Object | Users must be able to opt out of certain data processing (e.g., marketing). | Compliant | Compliant | Compliant | Compliant | Compliant | Respects digital autonomy; limits manipulative personalization, supports sustainable user experience. |

| Art. 25 Data Protection by Design & Default | Platforms must embed privacy by design, minimize data usage. | Lacking | Partial | Lacking | Lacking | Partial | Promotes efficient, future-ready, and resilient infrastructure design. |

| Art. 35 Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA) | High-risk processing (e.g., biometrics, profiling) requires DPIA. | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Lacking | Encourages careful risk planning, minimizing harm and costly technical debt. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sakka, S.; Liagkou, V.; Ferreira, A.; Stylios, C. Digital Boundaries and Consent in the Metaverse: A Comparative Review of Privacy Risks. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2026, 6, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010024

Sakka S, Liagkou V, Ferreira A, Stylios C. Digital Boundaries and Consent in the Metaverse: A Comparative Review of Privacy Risks. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2026; 6(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakka, Sofia, Vasiliki Liagkou, Afonso Ferreira, and Chrysostomos Stylios. 2026. "Digital Boundaries and Consent in the Metaverse: A Comparative Review of Privacy Risks" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 6, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010024

APA StyleSakka, S., Liagkou, V., Ferreira, A., & Stylios, C. (2026). Digital Boundaries and Consent in the Metaverse: A Comparative Review of Privacy Risks. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 6(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010024