An Improved Detection of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine

Abstract

1. Introduction

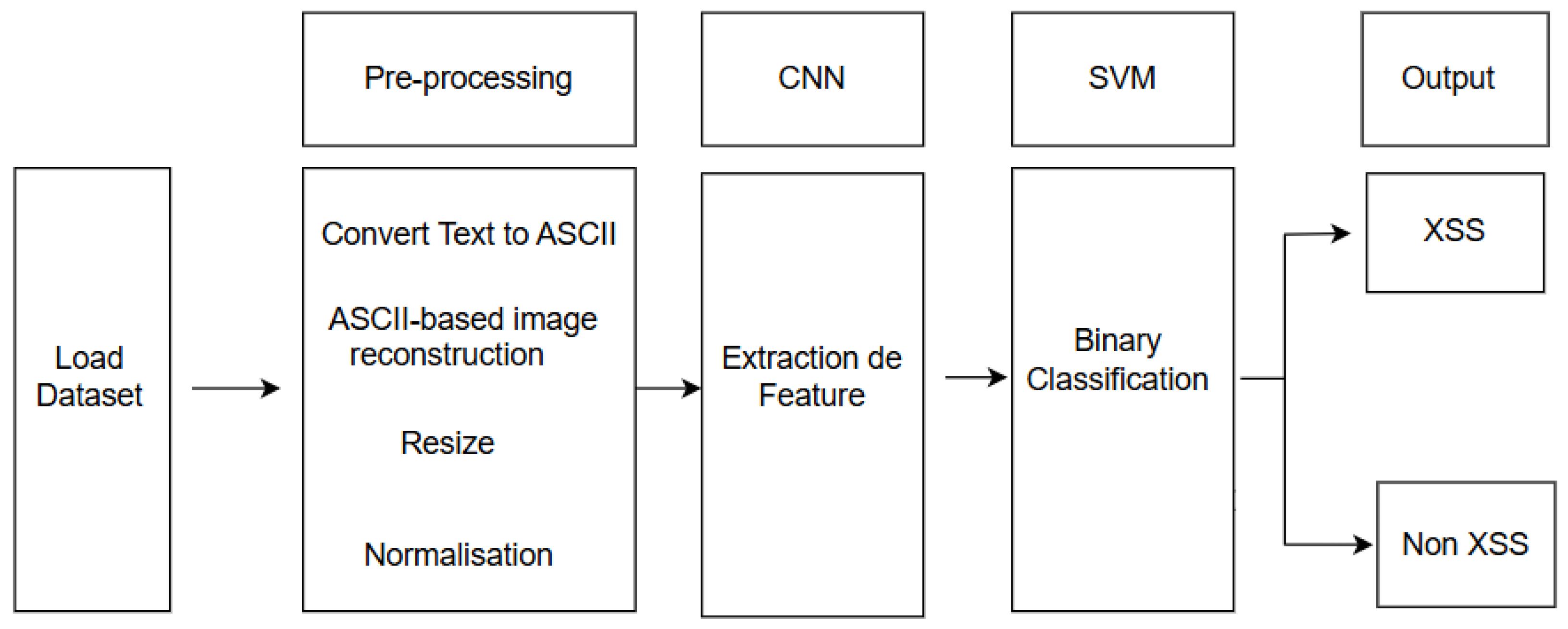

- Phase 1: ASCII encoding of the HTML code, followed by its conversion into an image.

- Phase 2: Automatic extraction of discriminative features from these images.

- Phase 3: Data classification using an SVM (Support Vector Machine) classifier.

- XSS attacks are detected using a hybrid model combining CNN and SVM. The CNN extracts features from images after being trained on a set of 64 × 64 pixel images. These images were generated by first converting the code to ASCII, then transforming it into grayscale images, before being used for the classification step.

- The results obtained using this hybrid model combining CNN and SVM are very accurate (99.7%) and balanced for all criteria evaluated, which will significantly improve the security of web applications by providing reliable defenses against sophisticated XSS threats.

- Optimization of SVM hyperparameters using GridSearchCV.

- The total time per query varies between 10 and 13 milliseconds, which is very low and perfectly suited for use in production. Our model offers a much better balance between computational cost and predictive efficiency, clearly outperforming traditional methods that rely solely on SVM.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

2.1.1. Stored XSS (Persistent)

2.1.2. XSS Reflected (Non-Persistent)

2.1.3. DOM-Based

2.2. Basic Concepts

2.2.1. ASCII Representation of the Sentence

2.2.2. ASCII-Based Image Reconstruction

2.2.3. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

- : The pixel value at position in the input image;

- : The weight of the kernel at position ;

- : The output feature map at position .

2.2.4. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- is the normal vector to the hyperplane (the direction perpendicular to it);

- b is the offset or bias term representing the distance of the hyperplane from the origin along the normal vector .

- is the class label (+1 or −1) for each training instance;

- is the feature vector for the i-th training instance;

- m is the total number of training instances.

2.3. Related Work

2.3.1. Detection of XSS Attacks Using Convolutional Neural Network

2.3.2. Detection of XSS Attacks Using SVM Algorithm

2.3.3. Detection of XSS Attacks Using a Hybrid CNN and Machine Learning Approach

2.3.4. Recapitulation: Study of XSS Detection Methods

3. Proposed Approach

3.1. Diagram of Approach

3.2. Algorithm Description

- Step 1:

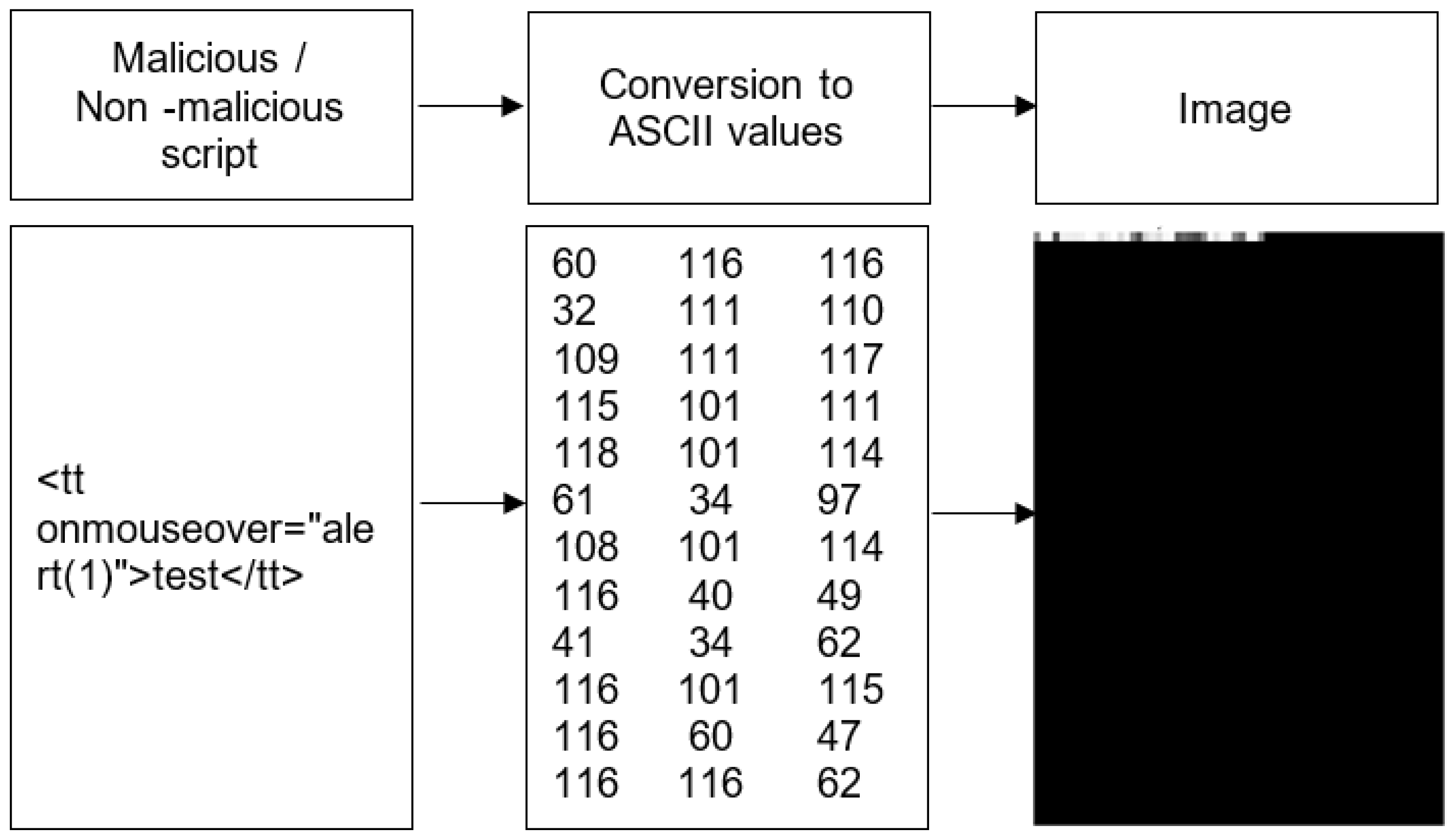

- Image Conversion: Each text payload is transformed into a grayscale image via ASCII encoding and normalization.

- Step 2:

- CNN Architecture: A three-layer convolutional neural network is constructed with batch normalization and dropout regularization to prevent overfitting.

- Step 3:

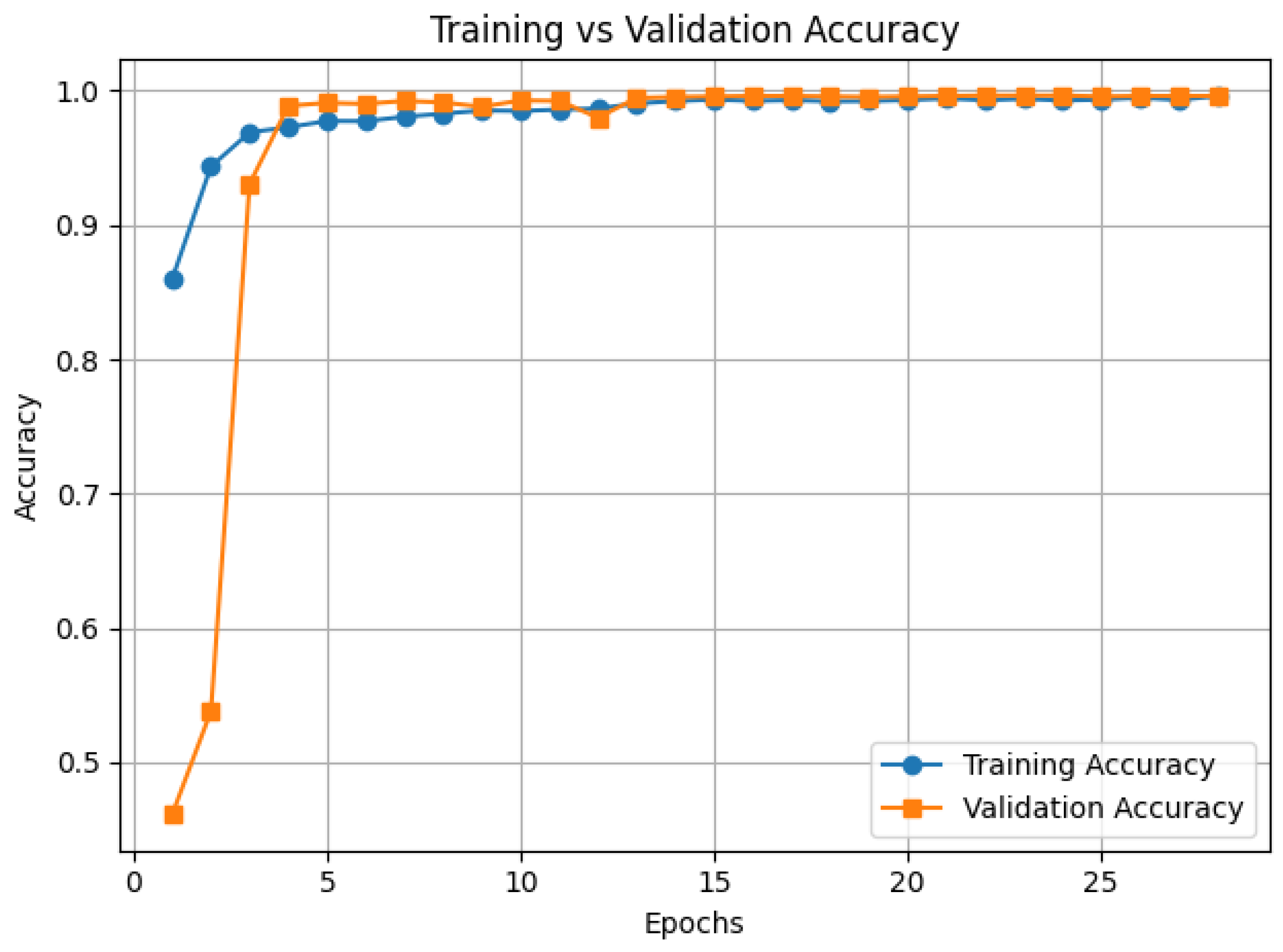

- CNN Training: The CNN is trained using Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss for 30 epochs.

- Step 4:

- Feature Extraction: 256-dimensional feature vectors are extracted from the penultimate dense layer.

- Step 5:

- Feature Normalization: Extracted features undergo Z-score normalization to ensure zero mean and unit variance.

- Step 6:

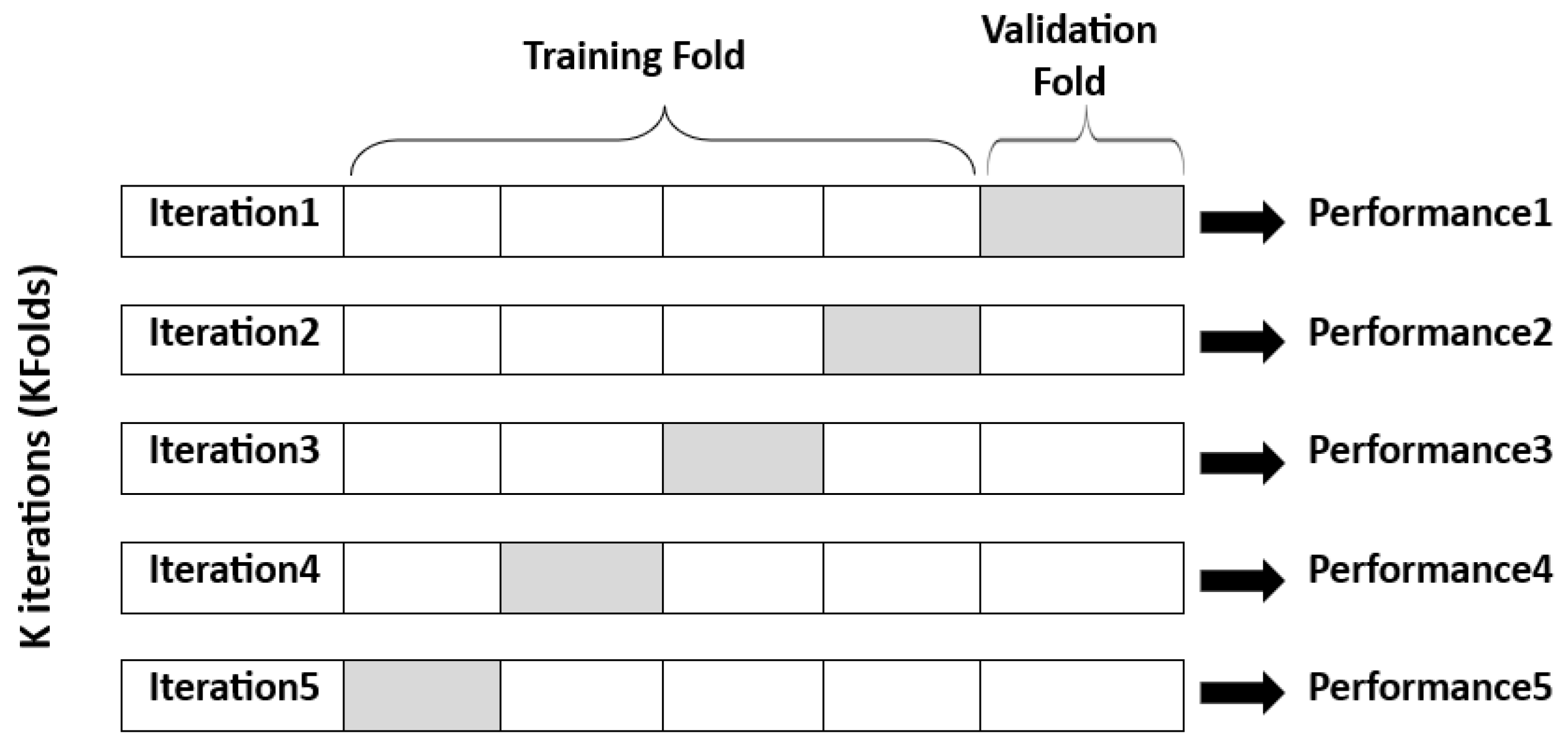

- SVM Optimization: A support vector machine classifier is optimized through grid search with 3-fold cross-validation.

- Step 7:

- Hybrid Model: The final model combines CNN feature extraction with SVM classification.

- Step 8:

- Performance Evaluation: Standard metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC) are computed.

| Algorithm 1: Detection xss with CNN + SVM |

|

3.3. Dataset

3.3.1. Dataset Description

- Sentence: A string of HTML or JavaScript text representing either normal web content or an attempted malicious injection.

- Label: An integer (0 or 1) indicating the nature of the content: 0 for non-malicious content and 1 for malicious content (XSS attack).

3.3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.4. Text-to-ASCII Conversion for Image Reconstruction

3.5. Architecture of the Model CNN

3.6. Classification SVM

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Performance Metrics

4.1.1. Accuracy

4.1.2. Recall

4.1.3. Precision

4.1.4. F1-Score

4.1.5. AUC (Area Under the Curve) of the Courbe ROC

4.1.6. K-Fold Cross-Validation

4.2. Results

4.3. SVM Hyperparameter Optimization

4.4. Accuracy Results

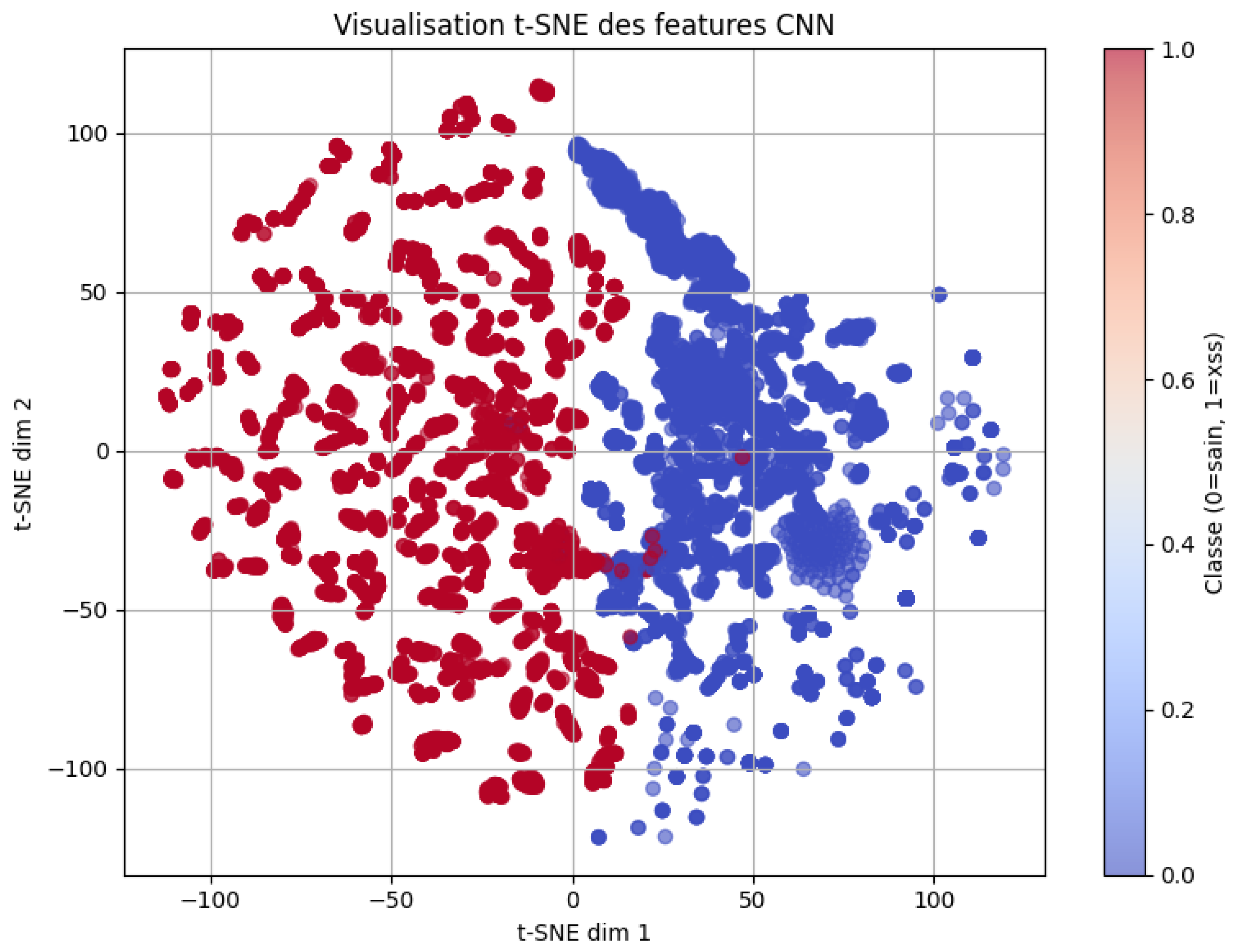

4.5. Visualization t-SNE

- Class 0: Represents code (normal) with the color blue.

- Class 1: Represents XSS (malicious) with the color red.

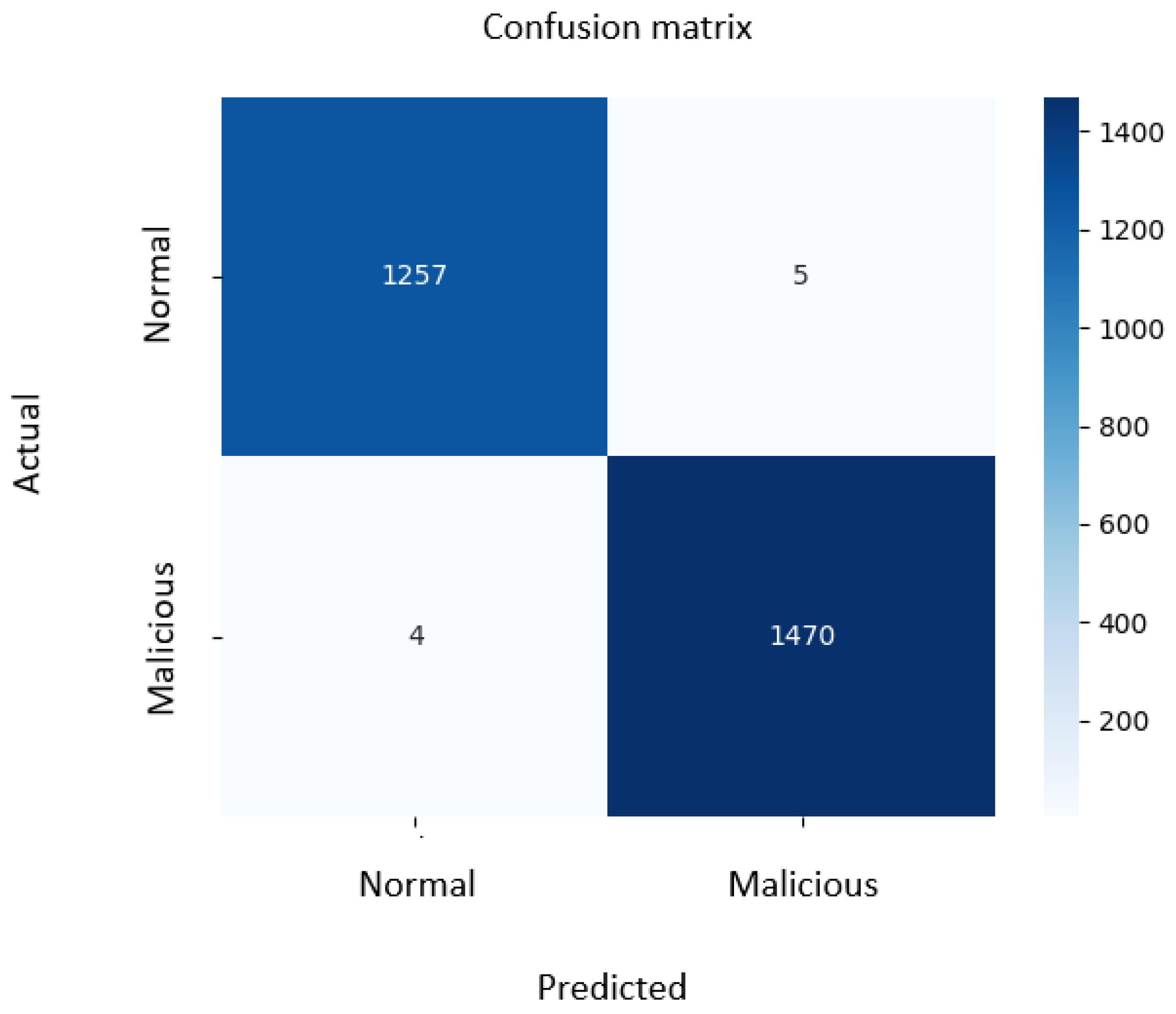

4.6. Confusion Matrix

4.7. Computational Cost and Real-Time Inference Performance

5. Discussion

6. Limitation of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| XSS | Cross-Site Scripting |

| OWASP | Open Web Application Security Project |

| MRBN | Modified ResNet and Network-in-Network |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ASCII | American Standard Code for Information Interchange |

| URL | Uniform Resource Locator |

| JS | JavaScript |

| t-SNE | t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding |

References

- OWASP. OWASP Top Ten. 2025. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-project-top-ten/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ayeni, B.K.; Sahalu, J.B.; Adeyanju, K.R. Detecting Cross-Site Scripting in Web Applications Using Fuzzy Inference System. J. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2018, 2018, 8159548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, U.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. A Survey of Detection Methods for XSS Attacks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 118, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamide, Y. Static Approximation of Dynamically Generated Web Pages. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW’05), Chiba, Japan, 10–14 May 2005; ACM Press: Chiba, Japan, 2005; p. 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupé, A.; Cui, W.; Jakubowski, M.H.; Peinado, M.; Kruegel, C.; Vigna, G. deDacota: Toward Preventing Server-Side XSS via Automatic Code and Data Separation. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer & Communications Security (CCS’13), Berlin, Germany, 4–8 November 2013; ACM Press: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, W.; Lin, Y. Efficient CNN Accelerator Based on Low-End FPGA with Optimized Depthwise Separable Convolutions and Squeeze-and-Excite Modules. AI 2025, 6, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Cheng, X.; Cheng, W.; Lin, Y. Few-Shot Image Classification Algorithm Based on Global–Local Feature Fusion. AI 2025, 6, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disawal, S.; Suman, U.; Rathore, M. Investigation of Detection and Mitigation of Web Application Vulnerabilities. Int. J. Comput. Appl. IJCA 2022, 184, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, S.; Maragliano, G.; Kim, J.; Tonella, P. XSS Adversarial Attacks Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Replication and Extension Study. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.E.; Torres, J.G.; Flores, P.; Benavides, D.E. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks and Mitigation: A Survey. Comput. Netw. 2020, 166, 106960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, H.; Triloka, J. Method for Detection and Mitigation of Cross-Site Scripting Attack on Multi-Websites. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology and Business (ICITB 2021), Bandar Lampung, Indonesia, 17 November 2021; pp. 26–32. Available online: https://jurnal.darmajaya.ac.id/index.php/icitb/article/view/3037/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Falana, O.J.; Ebo, I.O.; Tinubu, C.O.; Adejimi, O.A.; Ntuk, A. Detection of Cross-Site Scripting Attacks Using Dynamic Analysis and Fuzzy Inference System. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference in Mathematics, Computer Engineering and Computer Science (ICMCECS), Ayobo, Nigeria, 18–21 March 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Tarek, Z.; Darwish, Y.; Elseuofi, S.; Darwish, E.; Shams, M. Neutrosophic Encoding and Decoding Algorithm for ASCII Code System; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumar, S.; Kingston, Z. Evaluating Machine Learning Approaches for ASCII Art Generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sakka, M.; Ivanovici, M.; Chaari, L.; Mothe, J. A Review of CNN Applications in Smart Agriculture Using Multimodal Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamyani, R.; Alshammari, M. Machine Learning-Driven Detection of Cross-Site Scripting Attacks. Information 2024, 15, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, R.W.; Gaata, M.T. A Hybrid of CNN and LSTM Methods for Securing Web Application Against Cross-Site Scripting Attack. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2020, 21, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Feng, L.; Yu, Y.; Liao, W.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Zou, Y.; Liu, C.; Qu, L.; et al. Cross-Site Scripting Attack Detection Based on a Modified Convolution Neural Network. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 981739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Santhanavijayan, A.; Rajendran, B. Cross Site Scripting Attacks Classification Using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India, 25–27 January 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Xie, B. Detecting SQL Injection and XSS Attacks Using ASCII Code and CNN. In Network Simulation and Evaluation; Gu, Z., Zhou, W., Zhang, J., Xu, G., Jia, Y., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 2063, pp. 33–45. ISBN 978-981-9745-18-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lente, C.; Hirata, R., Jr.; Batista, D.M. An Improved Tool for Detection of XSS Attacks by Combining CNN with LSTM. In Proceedings of the Anais Estendidos do XXI Simpósio Brasileiro em Segurança da Informação e de Sistemas Computacionais, Florianis, Brazil, 12–15 September 2021; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://sol.sbc.org.br/index.php/sbseg_estendido/article/view/17333 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Nunan, A.E.; Souto, E.; Dos Santos, E.M.; Feitosa, E. Automatic Classification of Cross-Site Scripting in Web Pages Using Document-Based and URL-Based Features. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Cappadocia, Turkey, 1–4 July 2012; IEEE: Cappadocia, Turkey, 2012; pp. 702–707. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6249380/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Likarish, P.; Jung, E.; Jo, I. Obfuscated Malicious JavaScript Detection Using Classification Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2009 4th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE), Montreal, QC, Canada, 13–14 October 2009; IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009; pp. 47–54. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5403020/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Umehara, A.; Matsuda, T.; Sonoda, M.; Mizuno, S.; Chao, J. Consideration on the Cross-Site Scripting Attacks Detection Using Machine Learning. IPSJ SIG Tech. Rep. 2015, 2015, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi, B.; Ahmed, T.; Saikia, H.K. Detection of XSS Attacks in Web Applications: A Machine Learning Approach. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2021, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.M.; Ho, T.P.; Nam, H.T. A New Approach to Improving Web Application Firewall Performance Based on Support Vector Machine Method with Analysis of Http Request. J. Sci. Technol. Inf. Secur. 2022, 1, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, G.; Surantha, N. XSS Attack Detection with Machine Learning and N-Gram Methods. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Vitual, 13–14 August 2020; IEEE: Bandung, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 516–520. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9210946/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Banerjee, R.; Baksi, A.; Singh, N.; Bishnu, S.K. Detection of XSS in Web Applications Using Machine Learning Classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronics, Materials Engineering & Nano-Technology (IEMENTech), Kolkata, India, 2–4 October 2020; IEEE: Kolkata, India, 2020; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9270052/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Mereani, F.A.; Howe, J.M. Detecting Cross-Site Scripting Attacks Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications (AMLTA2018), Cairo, Egypt, 22–24 February 2018; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Hassanien, A.E., Tolba, M.F., Elhoseny, M., Mostafa, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 723, pp. 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokbal, F.M.M.; Wang, D.; Wang, X. Detect Cross-Site Scripting Attacks Using Average Word Embedding and Support Vector Machine. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2022, 4, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Abhishek, S.; Ravindran, R.; Anjali, T.; Shriamrut, V. AI-Driven Deep Structured Learning for Cross-Site Scripting Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application (ICIDCA), Uttarakhand, India, 14–16 March 2023; IEEE: Tirunelveli, India, 2023; pp. 701–709. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10099960/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Shah, S.H.; Hussain, S.S. Cross Site Scripting (XSS) Dataset for Deep Learning. Kaggle. 11 January 2024. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/syedsaqlainhussain/cross-site-scripting-xss-dataset-for-deep-learning/data (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Afifi, H.; Hsaini, A.M.; Merras, M.; Bouazi, A.; Chana, I. Enhanced Facial Recognition Using Parametrized ReLU Activation in Convolutional Neural Networks. In Intersection of Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, and Cutting-Edge Technologies: From Concepts to Applications in Smart Environment; Farhaoui, Y., Herawan, T., Lucky Imoize, A., Allaoui, A.E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1397, pp. 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.T.; Ma, R. Theoretical Foundations of t-SNE for Visualizing High-Dimensional Clustered Data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 23, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, K.H.; Osman, M.Z.; Anthony, T.; Ismail, M.A.; Abdullah, Z.; Alanda, A. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attack Detection. JOIV Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2024, 8, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Method | Data Type | Techniques Used | Accuracy/Results | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | Supervised classification of obfuscated JavaScript scripts | JavaScript scripts collected from the web (malicious vs. benign) | Naive Bayes, ADTree, SVM | 90–95% | The number of false positives is very low |

| [23] | Traditional ML | URLs and page content | SVM, NB | 94–98% | Malicious pages are classified with great accuracy. |

| [25] | Supervised classification of HTTP requests | URL extracts and web pages (plain text) | SVM (RBF kernel), Random Forest | >90% | XSS requests can be clearly separated from normal requests. |

| [28] | ML + n-gram | Web scripts (benign or malicious) | SVM, KNN, NB + n-gram | 98% | The n-gram method with SVM achieved high accuracy. |

| [29] | Traditional ML | JS + URL | SVM, KNN, RF, Logistic Regression | 98% (RF) | Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy and lowest FPR (0.34). |

| [26] | SVM Linear/Non-Linear | Payloads (XSS) | TF-IDF, SVM | 98% | Simple but effective. |

| [27] | SVM + HTTP analysis | Raw HTTP requests | TF-IDF, SVM | 99.99% | Very precise but computationally expensive. |

| [22] | Deep learning (3C-LSTM) | XSS URL (XSSed, Benign) | Word2Vec CBOW, CNN, LSTM, Softmax | 99.36% | High and stable accuracy. |

| [18] | Hybrid DL | XSS payloads | CNN + LSTM | 96–97% | Combines semantic extraction (Word2Vec) and deep classification. |

| [31] | SVM + embeddings | Word averages | SVM | 94% | High-level NLP + ML performance. |

| [19] | MRBN-CNN | HTML, URL | Modified ResNet + Network-in-Network | 99% | Very high accuracy with CNN. |

| [20] | CNN | HTML content and scripts | CNN | 98.62% | No specific figures provided. |

| [32] | Deep Learning (CNN + ML) | XSS data (simulated/real) | CNN + ML | >99.9% | Robust against complex XSS attacks, outperforms traditional models. |

| [17] | Comparative ML/DL | Real XSS (URL, HTML, JS) | SVM, CNN, RF, etc. | 99.78% (RF) | In-depth comparative study. |

| [21] | CNN + ASCII encoding | ASCII text | CNN | n/a | Detects both XSS and SQLi together. |

| Component | Layers (In Order) |

|---|---|

| Input | Grayscale image |

| Conv Block 1 |

Conv2D(32, , same, IncreaseRelu)

→ MaxPool() → BN → Dropout(0.25) |

| Conv Block 2 |

Conv2D(64, , same, IncreaseRelu)

→ MaxPool() → BN → Dropout(0.25) |

| Conv Block 3 |

Conv2D(128, , same, IncreaseRelu)

→ MaxPool() → BN → Dropout(0.25) |

| Flatten | Flatten() |

| Dense Block | Dense(256, IncreaseRelu, L2()) → BN → Dropout(0.5) |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0.9968 | 0.9960 | 0.9964 | 1262 |

| XSS | 0.9966 | 0.9973 | 0.9969 | 1474 |

| Overall Accuracy | - | - | 0.9969 | 2736 |

| Fold | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9953 |

| 2 | 0.9942 |

| 3 | 0.9945 |

| 4 | 0.9927 |

| 5 | 0.9949 |

| Mean ± Std | 0.9943 ± 0.0010 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN + SVM | 0.9965 | 0.9966 | 0.9973 | 0.9969 |

| CNN + Sigmoid | 0.9883 | 1.0000 | 0.9783 | 0.9890 |

| Step | Time per Batch | Batch Size | Time per Request |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN feature extraction | 231–242 ms | 32 | 7–8 ms |

| SVM classification | Not batch-based | 1 | 2–5 ms |

| Total inference time | 238 ± 8 ms | 32 | 10–13 ms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ayoubi, A.; Laaouina, L.; Jeghal, A.; Tairi, H. An Improved Detection of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2026, 6, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010018

Ayoubi A, Laaouina L, Jeghal A, Tairi H. An Improved Detection of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2026; 6(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyoubi, Abdissamad, Loubna Laaouina, Adil Jeghal, and Hamid Tairi. 2026. "An Improved Detection of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 6, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010018

APA StyleAyoubi, A., Laaouina, L., Jeghal, A., & Tairi, H. (2026). An Improved Detection of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Convolutional Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 6(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010018