Learning to Hack, Playing to Learn: Gamification in Cybersecurity Courses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Mastering Technology as a Prerequisite for Cybersecurity

- paid products from well-known editors such as anti-viruses, Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), firewalls, web protections, etc., which offer a high security level [29].

- free products whose counterpart is their low efficiency. These ones can be free versions of well-known products or outsiders seeking a new marketplace. However, they can also be fake products that install adware and/or pop-ups to gather (or even steal) personal data as much as they introduce new vulnerabilities [30].

- custom device configurations without any additional security software. They, however, require IS security awareness and deep knowledge of their technical aspects. For example, most people leave wireless interfaces open, spreading their data around and encouraging opportunistic attackers. These ones can be from newbies (often called ‘script kiddies’) to experts [31]. Depending on the skills of the attackers and their maliciousness, the device can be enrolled in a Bitcoin-mining (or Monero, or any cryptographic money) farm or will participate in a Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attack [32].

- Think as a cybercriminal—it is necessary to identify vulnerabilities and threats. Indeed, a criminal mind is not really intuitive, as it circumvents tools or habits to obtain what s/he is looking for. Phreakers used whistles to make free phone calls [33]; some hackers used optical LEDs to exfiltrate data from air-gapped computers [34] or even turned power supplies into speakers [34,35]. Devices may allow actions initially strictly unwanted by designers. A first objective of our course was to share such an idea with our students.

- Compare yourself to successful cybercriminals—students need to analyze successful attacks to understand the techniques and strategies commonly employed by attackers.

- Reconstruct the sequence of events—to find pieces of information about an attacker through students’ understanding of the criminalistic modus operandi.

2.2. Managing Individuals in the Face of Emerging Threats

- Unintentional: wrong actions from inexperienced, negligent or influenced employees; for example, inattentive clicks, input errors, accidental deletions of sensitive data, etc. [47].

- Intentional and non-malicious: deliberate actions from employees winning a benefit but without a desire to cause harm; for example, deferring backups, choosing a weak password, leaving doors open during sensitive discussions, etc. [48].

- Intentional and malicious: deliberate actions from employees with a desire to cause harm; for example, divulging sensitive data, introducing malicious software, etc. [49].

2.3. Gamification as a Pedagogical Lever in Cybersecurity Education

3. Design and Implementation of a Gamified Cybersecurity Course

- Three theoretic lessons about information systems, social engineering, insider threats, security lifecycle and cryptography.

- Three practical lessons or tutorials split into two themes: external and insider threats. These will be described in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, respectively, and rely on Section 2.1 and Section 2.2, respectively. After having chosen a theme, students focus on it.

- A gamified project detailed in Section 3.3 and relying on Section 2.3.

3.1. From Technology Mastery to the Management of External Cyber Threats

3.1.1. Tutorial 1—Let Us Hack It!

3.1.2. Tutorial 2—Know the Attackers

3.1.3. Tutorial 3—Find the Cat

3.2. From Individual Management to Awareness and Mitigation of Insider Threats

3.2.1. Tutorial 1—Unintentional Insider Threats

3.2.2. Tutorial 2—Intentional and Non-Malicious Insider Threats

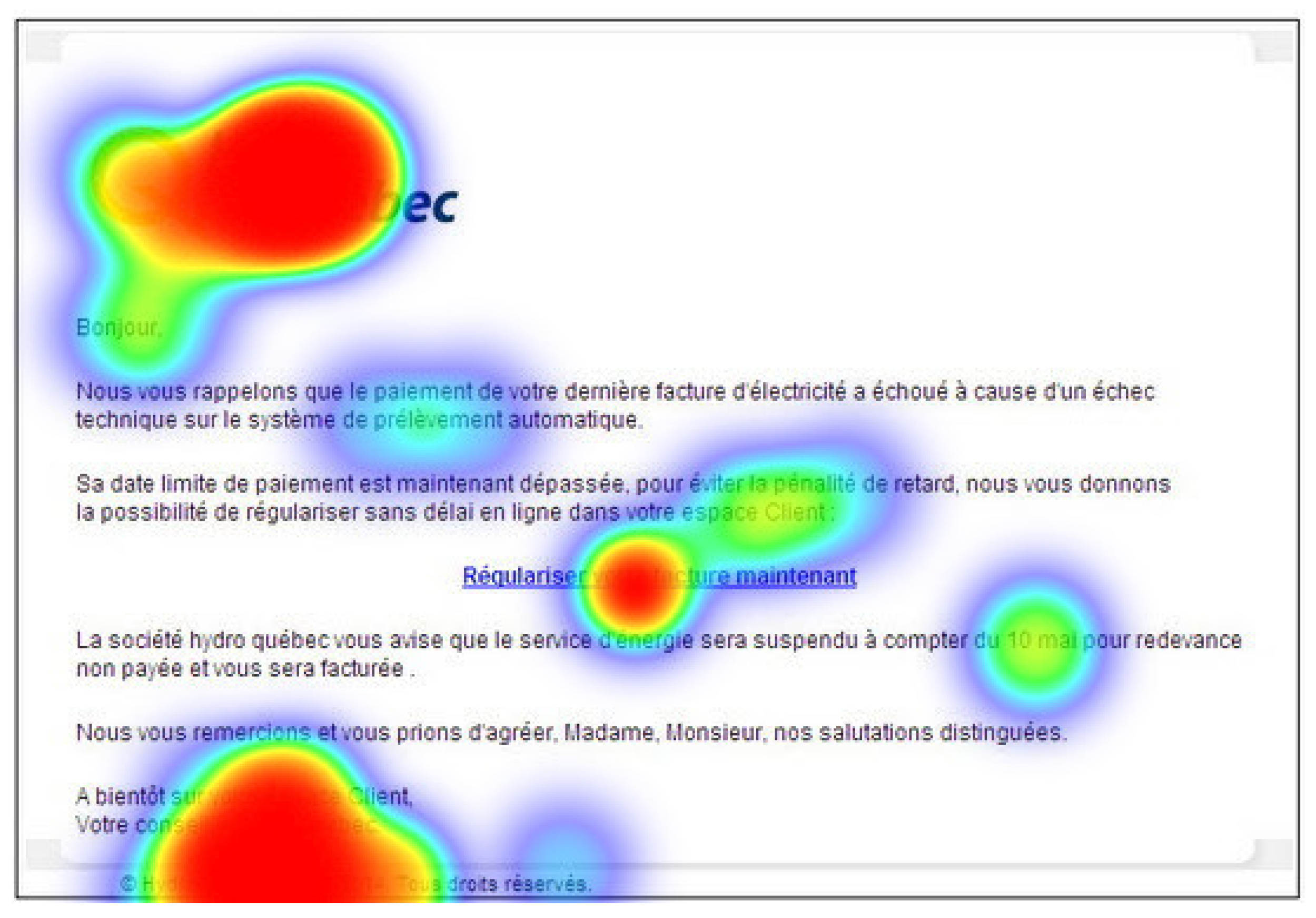

3.2.3. Tutorial 3—Intentional and Malicious Insider Threats

3.3. Capture the Flag as a Gamified Learning Scenario

3.3.1. Part 1—Hacking a Laptop (Common to All Groups)

3.3.2. Part 2—Deceiving Individuals (Different from One Group to Another)

3.4. Discussion, Limits and Ethical Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen, J.V.; Lowry, P.B.; Meservy, R.D.; McDonald, D.M. Genetic programming for prevention of cyberterrorism through dynamic and evolving intrusion detection. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi-Jun, W.; Hai-Tao, Z.; Ming-Hua, W.; Bao-Song, P. MSABMS-based approach of detecting LDoS attack. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, P.N.; Gasca, R.M.; Lefevre, L. FT-FW: A cluster-based fault-tolerant architecture for stateful firewalls. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassandoust, F.; Techatassanasoontorn, A.A.; Singh, H. Information Security Behaviour: A Critical Review and Research Directions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2020, Online, 15–17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sasse, M.A.; Brostoff, S.; Weirich, D. Transforming the ‘weakest link’—A human/computer interaction approach to usable and effective security. BT Technol. J. 2001, 19, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, C.; Von Solms, R. Towards information security behavioural compliance. Comput. Secur. 2004, 23, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willison, R.; Warkentin, M. Beyond Deterrence: An Expanded View of Employee Computer Abuse. MIS Quartely 2013, 37, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduin, P.E. Insider Threats; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, J. Improving user security behaviour. Comput. Secur. 2003, 22, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, K.D.; Carr, H.H.; Warkentin, M.E. Threats to information systems: Today’s reality, yesterday’s understanding. MIS Q. 1992, 16, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warkentin, M.; Willison, R. Behavioral and policy issues in information systems security: The insider threat. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlaney, J.; Benson, V. Cybersecurity as a social phenomenon. In Cyber Influence and Cognitive Threats; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Tlili, A.; Chang, T.W.; Zhang, X.; Nascimbeni, F.; Burgos, D. Disrupted classes, undisrupted learning during COVID-19 outbreak in China: Application of open educational practices and resources. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohmmed, A.O.; Khidhir, B.A.; Nazeer, A.; Vijayan, V.J. Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: The current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Nariman, D. Impact of the Interactive e-Learning Instructions on Effectiveness of a Programming Course. In Proceedings of the Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS-2020), Lodz, Poland, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 588–597. [Google Scholar]

- Adam-Ledunois, S.; Arduin, P.E.; David, A.; Parguel, B. Basculer soudain aux cours en ligne: Le regard des étudiants. In Le Libellio d’Aegis; AEGIS: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 16—Série Spéciale Coronam, Semaine 5; pp. 55–67. Available online: http://lelibellio.com/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloran, E.T. Knowledge, Attitudes, Anxiety, and Coping Strategies of Students during COVID-19 Pandemic. In Loss and Trauma in the COVID-19 Era; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Burian, S.; Horsburgh, J.; Rosenberg, D.; Ames, D.; Hunter, L.; Strong, C. Using Interactive Video Conferencing for Multi-Institution, Team-Teaching. Proc. ASEE Annu. Conf. Expo. 2013, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi, V.E.; Usrey, G.L. Cognitive Frustration and Learning. Decis. Sci. 1970, 1, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L.; Benson, V. Jigsaw teaching method for collaboration on cloud platforms. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 59, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Micco, M.; Rossman, H. Building a cyberwar lab: Lessons learned: Teaching cybersecurity principles to undergraduates. In Proceedings of the 33rd SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, Cincinnati, KY, USA, 27 February–3 March 2002; pp. 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Serik, M.; Tleumagambetova, D.; Tutkyshbayeva, S.; Zakirova, A. Integration of Cybersecurity into Computer Science Teachers’ Training: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar]

- Reix, R. Systemes d’Information et Management des Organisations; Vuibert: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The Internet of Things: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G. BYOD: Enabling the chaos. Netw. Secur. 2012, 2012, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Beyer, B. BeyondCorp: A new approach to enterprise security. login Mag. Usenix Sage 2014, 39, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ahvanooey, M.T.; Li, Q.; Rabbani, M.; Rajput, A.R. A Survey on Smartphones Security: Software Vulnerabilities, Malware, and Attacks. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 2017, 8, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Narang, H.; Clarke, D. An Overview of Mobile Malware and Solutions. J. Comput. Commun. 2014, 2, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R. Hackers Profiled—Who Are They and What Are Their Motivations? Comput. Fraud Secur. 2001, 2, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, M.; April, T.; Bailey, M.; Bernhard, M.; Bursztein, E.; Cochran, J.; Durumeric, Z.; Halderman, J.A.; Invernizzi, L.; Kallitsis, M.; et al. Understanding the Mirai Botnet. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 1093–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick, K.; Simon, W. The Art of Deception: Controlling the Human Element of Security; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guri, M.; Hasson, O.; Kedma, G.; Elovici, Y. An optical covert-channel to leak data through an air-gap. In Proceedings of the 2016 14th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Auckland, New Zealand, 12–14 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, M. POWER-SUPPLaY: Leaking Data from Air-Gapped Systems by Turning the Power-Supplies Into Speakers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.00395. [Google Scholar]

- Seebruck, R. A typology of hackers: Classifying cyber malfeasance using a weighted arc circumplex model. Digit. Investig. 2015, 14, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 22, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwebu, K.L.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.Y. Information security policy noncompliance: An integrative social influence model. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 220–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, T.; Yim, M.S.; D’Arcy, J.; Nam, K.; Rao, H.R. Examining employee security violations: Moral disengagement and its environmental influences. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 1135–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, G.M.; Matza, D. Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: An empirical study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduin, P.E. A cognitive approach to the decision to trust or distrust phishing emails. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2023, 30, 1263–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, V.; McAlaney, J. Emerging Cyber Threats and Cognitive Vulnerabilities; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Triplett, W.J. Addressing Human Factors in Cybersecurity Leadership. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlaney, J.; Frumkin, L.; Benson, V. Psychological and Behavioral Examinations in Cyber Security; Advances in Digital Crime, Forensics, and Cyber Terrorism (2327-0381); IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, J.; Stam, K.; Mastrangelo, P.; Jolton, J. Analysis of end user security behaviors. Comput. Secur. 2005, 24, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Yuan, Y.; Archer, N.; Connely, C. Understanding Nonmalicious security violations in the workplace: A composite behavior model. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 203–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shropshire, J. A canonical analysis of intentional information security breaches by insiders. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2009, 17, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.C. Solutions for counteracting human deception in social engineering attacks. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1130–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Y.T.; Scott, J.L. An investigation of barriers to knowledge transfer. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Lane, H.W.; White, R.E. An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday/Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hatten, K.J.; Rosenthal, S.R. Reaching for the Knowledge Edge: How the Knowing Corporation Seeks, Shares and Uses Knowledge for Strategic Advantage; American Management Association, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Razmerita, L.; Kirchner, K.; Hockerts, K.; Tan, C.W. Modeling collaborative intentions and behavior in Digital Environments: The case of a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2020, 19, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenkaj, B.; Stilo, G.; Madeddu, L. Challenges and Solutions to the Student Dropout Prediction Problem in Online Courses. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Online, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 3513–3514. [Google Scholar]

- Maitlo, A.; Ameen, N.; Peikari, H.R.; Shah, M. Preventing identity theft. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1184–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspit, J.J.; D’Souza, D.E. Using the community of inquiry framework to introduce wiki environments in blended-learning pedagogies: Evidence from a business capstone course. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siala, H.; Kutsch, E.; Jagger, S. Cultural influences moderating learners’ adoption of serious 3D games for managerial learning. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 424–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustar, P. Technology management education: Innovation and entrepreneurship at MINES ParisTech, a leading French engineering school. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, E.; Wildman, J.L.; Piccolo, R.F. Using simulation-based training to enhance management education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 559–573. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, P.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cogn. Instr. 1991, 8, 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive technology: Some procedures for facilitating learning and problem solving in mathematics and science. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Upper Sadle River, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, S.; Fletcher, J.D.; Wind, A.P. Game-based learning. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 485–503. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, J. A Framework and Exploration of a Cybersecurity Education Escape Room. Ph.D. Thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saridakis, G.; Lai, Y.; Muñoz Torres, R.I.; Gourlay, S. Exploring the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An instrumental variable approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1739–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruguier, F.; Lecointre, E.; Pradarelli, B.; Dalmasso, L.; Benoit, P.; Torres, L. Teaching Hardware Security: Earnings of an Introduction proposed as an Escape Game. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Remote Engineering and Virtual Instrumentation, Athens, GA, USA, 26–28 February, 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 729–741. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, K.; Ishaq, K.; Nawaz, N.A.; Rosdi, F.; Dogar, A.B.; Khan, F.A. Unlocking cybersecurity: A game-changing framework for training and awareness—A systematic review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 2025, 9982666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, D.P.D.; Sundarraj, R.P. Designing game-based learning artefacts for cybersecurity processes using action design research. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2025, 67, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, A.; Womack, C.; Orton, P. Collaborative online international learning as a third space to improve students’ awareness of cybersecurity. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 13835–13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silic, M.; Lowry, P.B. Using Design-Science Based Gamification to Improve Organizational Security Training and Compliance. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 37, 129–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, V.; McAlaney, J.; Frumkin, L.A. Emerging threats for the human element and countermeasures in current cyber security landscape. In Cyber Law, Privacy, and Security: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1264–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Towards an Innovative Model for Cybersecurity Awareness Training. Information 2024, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaravi, Y. Using hackathons to teach management consulting. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2020, 57, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, G.; Mulligan, C. Digital Innovation: The Hackathon Phenomenon. Creativeworks London. 2014. Available online: http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/11418 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- NIST. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1; Technical Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Strom, B.E.; Applebaum, A.; Miller, D.P.; Nickels, K.C.; Pennington, A.G.; Thomas, C.B. MITRE ATT&CK: Design and Philosophy; Technical Report; MITRE Corp: Bedford, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shaer, R.; Spring, J.M.; Christou, E. Learning the Associations of MITRE ATT&CK Adversarial Techniques. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.01654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damart, S.; David, A.; Klasing Chen, M.; Laousse, D. Turning managers into management designers: An experiment. In Proceedings of the XXVIIème Conférence de l’AIMS, Montpellier, France, 6–8 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sagarin, B.J.; Mitnick, K.D. The path of least resistance. In Six Degrees Of Social Influence: Science, Application, and the Psychology of Robert Cialdini; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muscanell, N.L.; Guadagno, R.E.; Murphy, S. Weapons of influence misused: A social influence analysis of why people fall prey to internet scams. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.; Idris, B.; Saridakis, G.; Benson, V. Information and communication technologies: A curse or blessing for SMEs? In Emerging Cyber Threats and Cognitive Vulnerabilities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.H.; Jones, P.; Choudrie, J. Cybercrimes prevention: Promising organisational practices. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, Z.; Dintakurthy, Y. Gamification of Cybersecurity Education for K-12 Teachers. J. Comput. Sci. Coll. 2025, 40, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Videnovik, M.; Filiposka, S.; Trajkovik, V. A novel methodological approach for learning cybersecurity topics in primary schools. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 22949–22969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H. Cybersecurity Matters for Primary School Students: A Scoping Review of the Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2025, 18, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beel, J.; Langer, S.; Genzmehr, M.; Gipp, B.; Nürnberger, A. A Comparison of Offline Evaluations, Online Evaluations, and User Studies in the Context of Research-Paper Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries (TPDL), Poznań, Poland, 14–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laupper, E.; Balzer, L.; Berger, J.L. Online vs. Offline Course Evaluation Revisited: Testing the Invariance of a Course Evaluation Questionnaire Using a Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis Framework. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2020, 32, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkovic, J.; Peterson, P.A.H. Class Capture-the-Flag Exercises. In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX Summit on Gaming, Games, and Gamification in Security Education (3GSE 14), San Diego, CA, USA, 8 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, J.; Ischi, M.; Perkins, D. Evolution of different dual-use concepts in international and national law and its implications on research ethics and governance. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2014, 20, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawil, T.N. Ethical implications for teaching students to hack to combat cybercrime and money laundering. J. Money Laund. Control 2024, 27, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.; Goel, S. Improving Ethics Surrounding Collegiate-Level Hacking Education: Recommended Implementation Plan. MCA J. 2024, 7, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hynninen, T. Student Perceptions of Ethics in Cybersecurity Education. In Proceedings of the Conference on Technology Ethics (Tethics), Turku, Finland, 18–19 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, J. A Study on Ethical Hacking in Cybersecurity Education Within the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arduin, P.-E.; Costé, B. Learning to Hack, Playing to Learn: Gamification in Cybersecurity Courses. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2026, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010016

Arduin P-E, Costé B. Learning to Hack, Playing to Learn: Gamification in Cybersecurity Courses. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2026; 6(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleArduin, Pierre-Emmanuel, and Benjamin Costé. 2026. "Learning to Hack, Playing to Learn: Gamification in Cybersecurity Courses" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 6, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010016

APA StyleArduin, P.-E., & Costé, B. (2026). Learning to Hack, Playing to Learn: Gamification in Cybersecurity Courses. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp6010016