1. Introduction

Cybersecurity has become a paramount concern for organizations across all sectors. However, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) continue to face disproportionate challenges due to constrained resources, limited expertise, and low cybersecurity awareness. As businesses embrace digital transformation, safeguarding digital assets becomes increasingly vital. In this context, the evolution from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 has significant implications for cybersecurity readiness, particularly within the SME sector [

1].

Industry 4.0 emphasized automation, interconnectivity, and real-time data exchange through technologies such as cyber-physical systems, IoT, and cloud computing. While this industrial revolution improved efficiency and productivity, it also introduced new vulnerabilities by expanding the attack surface. Industry 5.0, in contrast, builds upon these foundations by integrating human-centric approaches with advanced technologies—such as artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and robotics—to promote resilience, sustainability, and collaboration between humans and intelligent systems. This shift underscores a more ethical, personalized, and adaptive technological environment that can support more secure digital infrastructures.

For SMEs, adopting Industry 5.0 represents an opportunity to drive innovation, improve agility, and enhance cybersecurity resilience. However, the integration of such advanced technologies also introduces several barriers, including financial constraints, a lack of technical know-how, and challenges in implementation. Overcoming these issues requires a strategic investment in digital literacy, partnerships with technology providers, and the development of scalable and tailored cybersecurity frameworks [

2].

Despite these potential benefits, SMEs remain highly vulnerable to cyber threats due to limited cybersecurity capabilities. While large corporations have access to comprehensive cybersecurity resources, SMEs often lack the necessary defenses to prevent, detect, and respond to cyberattacks. This vulnerability is highlighted in Rawindaran’s (2023) study, which identifies significant gaps in cybersecurity knowledge and practices among SMEs [

3]. The study calls for targeted, industry-specific interventions to mitigate these risks, emphasizing the need for customized awareness programs and human-centered security measures.

Building upon this foundation, the present study introduces the enhanced ROHAN model, a comprehensive cybersecurity framework tailored to SMEs. This model focuses on customized cybersecurity education based on industry type, employee roles, and educational backgrounds. It is further refined to integrate with the Cyber Guardian Framework (CGF), enhancing resilience through AI-powered risk assessments, automation, and cybersecurity standardization.

The primary objectives of this study are as follows:

Conduct a comprehensive assessment of cybersecurity knowledge and awareness within the SME sector through a systematic literature review.

Evaluate the impact and effectiveness of cybersecurity awareness programs on SME cybersecurity behaviors and risk mitigation.

Identify core barriers—financial, technical, and organizational—that hinder effective cybersecurity adoption in SMEs.

Introduce and validate the enhanced ROHAN model and its integration with the CGF to provide a scalable roadmap for cybersecurity resilience.

By aligning with Industry 5.0 principles and utilizing a mixed-methods approach—including surveys, interviews, and advanced data analytics—this research contributes evidence-based insights and actionable strategies to close critical cybersecurity knowledge gaps and enhance SME readiness in an increasingly digital landscape.

2. Literature Review

Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of cybersecurity awareness in SMEs and the broader impact of cybersecurity practices on organizational resilience. For instance, Falowo, O.I. (2023) explored the relationship between cybersecurity training and the reduction of cyber incidents in SMEs, finding a significant decrease in successful attacks following the implementation of targeted training programs [

4]. Similarly, a study by AlDaajeh, S. (2022) emphasized the role of continuous education and awareness in maintaining a robust cybersecurity posture within small businesses [

5]. Complementing these findings, Hoong, Y., Rezania, D., and Baker, R. (2024) examined the effectiveness of government-led cybersecurity initiatives aimed at SMEs, noting that while these programs are beneficial, their reach and impact are often limited by the SMEs’ resource constraints and varying levels of engagement [

6]. In another relevant study, Chen, Z.S. (2024) investigated the barriers to cybersecurity adoption in SMEs, identifying cost, complexity, and a lack of perceived relevance as the primary obstacles [

7].

A survey conducted by the National Cyber Security Alliance (2020) revealed that a significant percentage of SMEs do not prioritize cybersecurity due to a lack of understanding of the risks involved [

8]. This aligns with the findings of Smith, K.T. (2019), who noted that many SME owners underestimate the potential impact of cyber-attacks on their business operations [

9]. Building upon research by Rawindaran (2023) [

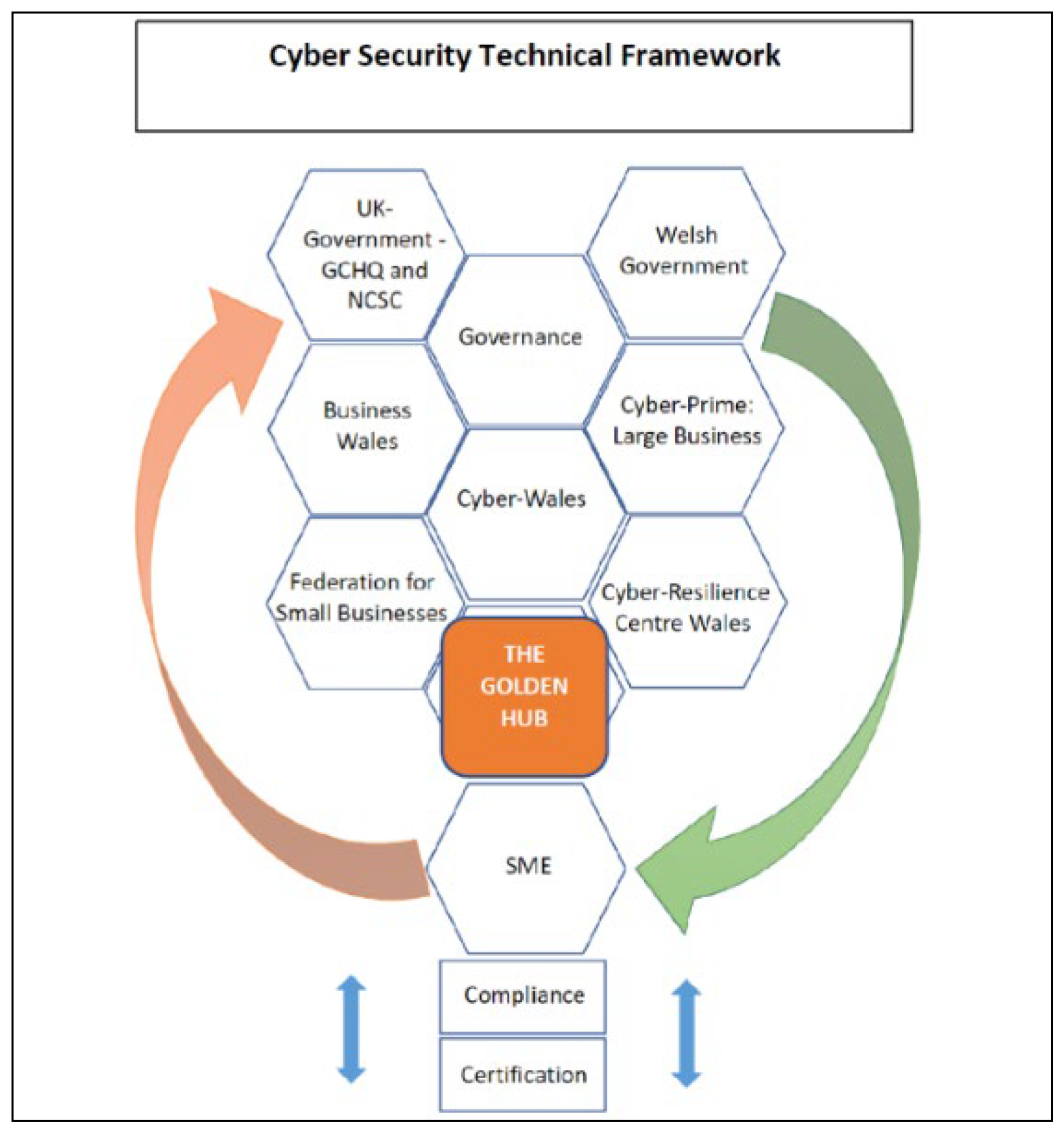

3], which highlighted the need for improved cybersecurity awareness among Welsh SMEs, initiatives like “The Golden Hub” offer a promising solution. The theoretical framework of the Golden Hub aims to empower SMEs in Wales to achieve a state of “Cyber Awareness” and implement effective cybersecurity measures, as shown in

Figure 1.

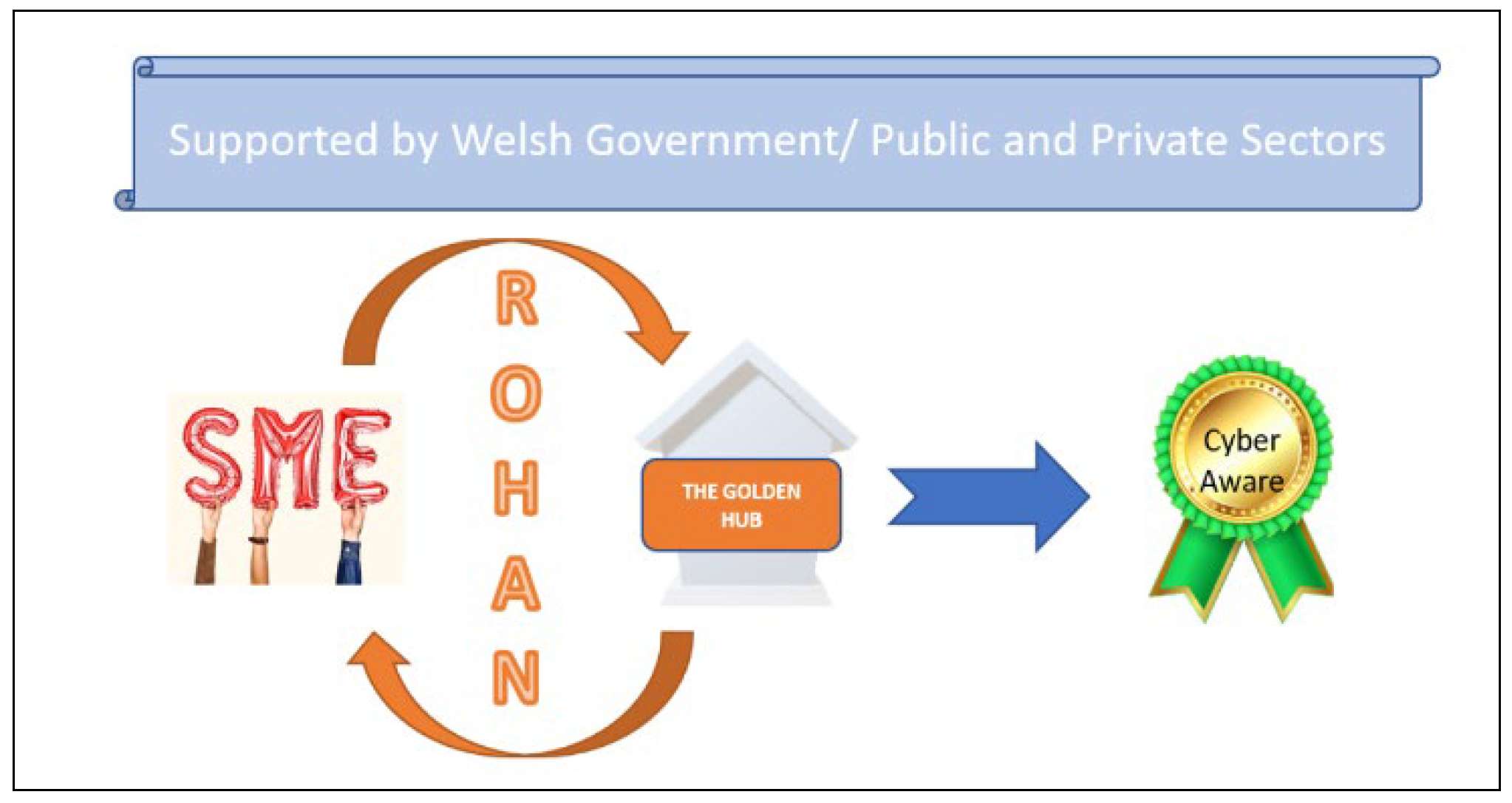

Welsh SMEs can participate in a program that assesses their current level of cybersecurity awareness and preparedness. This assessment culminates in a rating on a scale, potentially ranging from “Cyber Red” (low awareness and inadequate measures) to “Cyber Green” (high awareness and robust security measures). Upon achieving a “Cyber Green” rating, SMEs can display a certificate or badge to showcase their commitment to cybersecurity, potentially fostering trust with customers, as shown in

Figure 2.

The Golden Hub, as shown in

Figure 2, serves as a central resource for SMEs on their journey towards cybersecurity awareness. They offer guidance, support, and a series of assessments to help SMEs improve their cyber posture theoretically. By achieving a positive rating, SMEs can not only enhance their cyber resilience but also potentially benefit from being included in the Welsh Government’s Cyber Action Plan for 2023. The ROHAN model from this research offers a theoretical framework for measuring cyber resilience and serves as an internal guidance system that is documented. The model offers a holistic approach to cyber hygiene and cyber resilience, specifically designed to support Welsh SMEs. By following the step-by-step approach outlined in the ROHAN model, SMEs can proactively prepare their businesses for cyberattacks. The model empowers them to develop internal processes for handling such situations, fostering a more secure digital environment as described in

Figure 3.

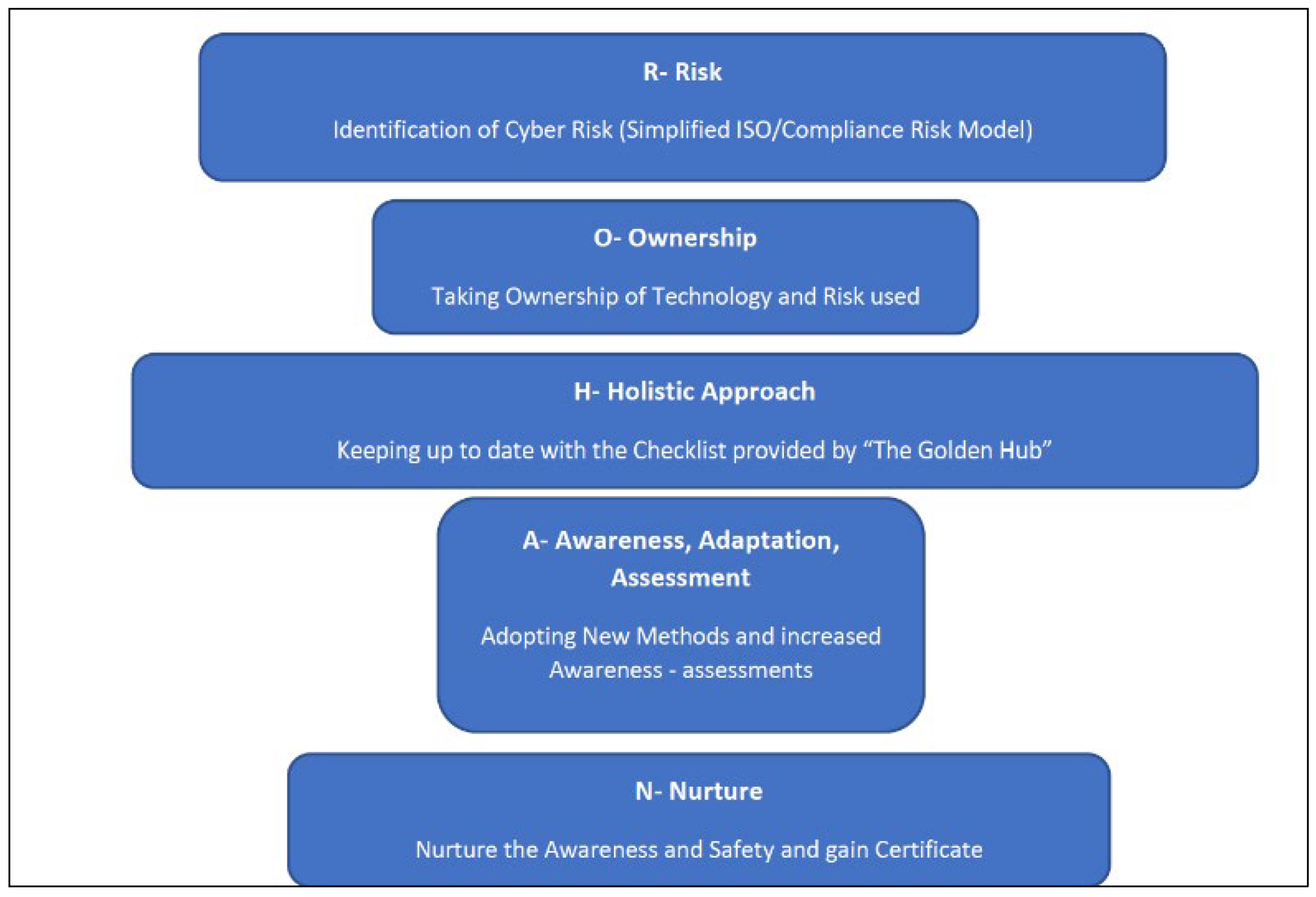

The ROHAN model offers a step-by-step approach for Welsh SMEs to achieve “Cyber Aware” status. In its current state, it encompasses five key aspects:

Risk Identification: SMEs learn to identify cyber risks within their business model. This results in a customized risk checklist aligned with governance and compliance policies. This step also helps develop a simplified and cost-effective path to achieve compliance.

Ownership: This step collaborates with SMEs’ supply chains to identify “fit-for-purpose” and affordable intelligent software solutions, empowering SMEs to take ownership of their cyber risk and technology. It also makes SMEs aware of their threats and countermeasures.

Holistic Approach: The ROHAN model emphasizes a calm and mindful approach to risk assessment. This includes ongoing communication and support within the SME structure.

Awareness, Adaptation, and Assessment: Through a series of training sessions and assessments, SMEs develop the necessary awareness and skills to adapt their business practices in line with the evolving threat landscape. Successful completion of this stage leads to a “Cyber Green” certification, signifying the SME’s achievement of cyber awareness.

Nurturing Awareness: This step fosters a continuous learning environment for SMEs, ensuring they stay ahead of cyber threats through ongoing support and awareness programs.

The important benefits of the existing ROHAN model for SMEs highlight the “H:Holistic” approach, which addresses both cyber hygiene practices (preventative measures) and cyber resilience strategies (response and recovery). Step-by-step guidance in the model provides a clear roadmap for SMEs to follow, making cybersecurity preparedness more manageable. The tailored implementation in the existing model can be adapted to the specific needs and resources of each SME.

This study clarifies the purpose of the ROHAN model and emphasizes its benefits for Welsh SMEs and focuses on the model’s step-by-step approach to its nature and adaptability. The references to Rawindaran’s (2023) [

3] research will build a foundation for the initiative’s importance. By following these steps, SMEs can address technology gaps, strengthen organizational structures, and enhance human awareness, which are all crucial aspects highlighted in the research [

3] for achieving “Cyber Aware” status. According to the study, Wales, with an estimated population of approximately 3.16 million as of mid-2023, ranks among the smaller nations in Europe by population. It shares demographic similarities with countries such as Lithuania (2.83 million), Albania (2.87 million), and Armenia (around 2.8 million). Despite its modest population size, Wales has a relatively high population density of about 152 people per square kilometer—greater than many larger European countries, including Austria, Denmark, Slovenia, Spain, and Romania.

Economically, Wales reported a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of approximately £85.4 billion in 2022. In comparison, Estonia—though smaller in population at roughly 1.3 million—had a GDP of around USD 40 billion in 2023. These figures suggest that Wales performs on par with, or above, countries of similar or even smaller size. However, direct comparisons should consider differences in economic structures, industrial bases, and regional governance, which significantly influence economic output and resilience.

Several other studies have highlighted the importance of clear communication and fostering a cybersecurity culture within the organization. Hijji, M. (2022) proposed a framework specifically designed for SMEs, focusing on delivering cybersecurity training in a way that is easily understood and retained by non-technical staff [

10]. Similarly, Chaudhary, S. (2023) emphasizes the importance of ongoing awareness campaigns and employee engagement in building a strong cybersecurity culture within SMEs, though they do not present a specific framework [

11]. Aligning training programs with the specific needs of an SME is critical for effectiveness. Gupta et al. (2023) introduce a heuristic approach that emphasizes conducting needs assessments before designing training initiatives [

12]. This aligns with the broader concept of using practical, experience-based methods (heuristics) to solve problems, as noted by the authors. While some studies do not present specific training frameworks, they contribute valuable insights into building cybersecurity resilience and improving preparedness in SMEs. Notably, Gupta et al. (2023) [

12] discuss the role of government in fostering cybersecurity awareness within SMEs, highlighting the potential for multi-stakeholder approaches.

Existing research focuses on developing training programs tailored to the needs of non-technical staff in SMEs, emphasizing clear communication, building a cybersecurity culture, and conducting needs assessments. In contrast, Rawindaran et al. (2023) [

3] proposed the ROHAN model, which goes beyond training by outlining a comprehensive process for building cybersecurity resilience in organizations. This model incorporates risk assessment, ownership by staff at all levels, a holistic view of cybersecurity, and continuous improvement through nurturing a cybersecurity culture. An improved ROHAN model could prove even more beneficial by incorporating elements from the reviewed studies. For instance, integrating needs assessments from Gupta et al. (2023) [

12] could ensure training aligns with the specific vulnerabilities of an SME. Furthermore, adopting clear communication strategies could enhance staff understanding and ownership within the ROHAN framework. By combining these elements, the ROHAN model has the potential to be a highly effective approach for building a robust cybersecurity posture within SMEs. SMEs will continue to face unique challenges in ensuring cybersecurity due to limited resources and technical expertise. This necessitates tailored training programs for non-technical staff, emphasizing clear communication and fostering a culture of security.

Several of these studies highlight the importance of needs assessments in designing effective training programs for SMEs [

12]. This aligns with the concept of a heuristic approach, which emphasizes practical methods for problem-solving based on experience and trial and error. By conducting needs assessments, training programs can be tailored to address the specific vulnerabilities faced by individual SMEs, maximizing the effectiveness of training initiatives [

12]. Beyond training, fostering a strong cybersecurity culture within the organization is crucial. Research by Da Veiga, A., et al. (2020) emphasizes the importance of ongoing awareness campaigns and employee engagement in building a culture of security [

13]. This aligns with the multi-stakeholder approach, which highlights the role of government and industry collaboration in fostering cybersecurity awareness within SMEs. Collaborative efforts can promote information sharing and resource exchange, further enhancing overall cyber resilience.

The research also acknowledges the limitations of solely focusing on internal training within SMEs. Gupta et al. (2023) [

12] examine the role of government initiatives in promoting cybersecurity awareness among SMEs. Government-sponsored training programs, resource sharing, and financial assistance can provide valuable support for SMEs in bolstering their cyber defenses.

In conclusion, effectively addressing cybersecurity training for non-technical employees in SMEs requires a multi-faceted approach. Academic research highlights the importance of clear communication, fostering a cybersecurity culture, and tailoring training programs to address specific SMEs. Furthermore, collaborative efforts involving government, industry, and SMEs themselves can strengthen overall cyber resilience. By implementing a combination of these strategies, SMEs can empower their non-technical workforce to play a crucial role in safeguarding the organization from cyber threats.

Academic research consistently emphasizes the need for accessible and tailored cybersecurity training programs for SMEs. To address this critical need, several companies offer online training platforms specifically designed for businesses, with features catering directly to the resource constraints and unique requirements of SMEs.

These online platforms often incorporate modular course structures, allowing SMEs to select training modules that directly address their identified vulnerabilities and training needs. This ensures a high degree of efficiency and effectiveness, maximizing the return on investment for SMEs with limited training budgets. For example, KnowBe4 offers a library of training modules that can be customized to address specific industries and attack vectors faced by SMEs [

14]. Similarly, Cybereason Security Awareness Training provides a modular platform with bite-sized learning modules that can be easily integrated into busy employee schedules, promoting accessibility and knowledge retention [

15].

Furthermore, many platforms incorporate gamification elements to enhance engagement and knowledge retention. Interactive elements, such as points, badges, and leaderboards, can make the training process more enjoyable and impactful, fostering a more positive learning experience for employees [

16]. PhishLabs offers gamified phishing simulations that allow employees to test their skills in a safe environment, identifying potential weaknesses and areas for improvement [

17]. Beyond online training platforms, companies offer services to create and deliver clear and engaging cybersecurity awareness content specifically tailored to SMEs. This includes the development of courses, presentations, and video content that is aligned with the specific needs and language of the target audience within an SME [

18]. Wombat Security Awareness Training, for instance, develops customized training materials that resonate with employees at all levels within an organization [

19]. Additionally, companies like InfoSec Institute Security Awareness Training offer engaging social media campaigns specifically designed for various platforms, leveraging these channels to reach a wider audience within the organization and raise overall cybersecurity awareness [

20]. Phishing simulations, another service offered by many content creation companies, allow SMEs to test employee preparedness and identify areas where additional training or awareness campaigns may be needed [

21].

The limited cybersecurity expertise within SMEs is another significant challenge highlighted. Consulting firms offer services to assist SMEs in developing and implementing effective cybersecurity strategies, addressing this critical gap. Needs assessments, a core service offered by these firms, identify the specific cybersecurity risks and vulnerabilities faced by an SME, providing a foundation for creating a customized cybersecurity strategy [

22]. Consulting firms like PwC Cybersecurity Services utilize needs assessments to inform the development of tailored cybersecurity policies and procedures for SMEs [

23]. These well-defined policies ensure consistency and compliance within the organization, empowering employees to make informed decisions regarding cybersecurity practices. Additionally, consulting firms offer incident response planning services, which involve developing a plan for how to respond to a cybersecurity incident. A well-defined incident response plan minimizes downtime and potential damage, allowing for faster and more effective mitigation strategies in the event of an attack. KPMG Cybersecurity and Deloitte Cyber Risk Services are just a few examples of consulting firms offering incident response planning services tailored to the specific needs of SMEs [

24]. Commercially available solutions complement academic research on cybersecurity training for SMEs. From online platforms with customizable training modules to awareness content creation and consulting services, these solutions address the unique challenges faced by SMEs and empower them to build a more robust cybersecurity posture. By leveraging a combination of these solutions alongside academic insights, SMEs can create a comprehensive and effective cybersecurity training program for their non-technical employees.

While much of the existing literature emphasizes the cybersecurity vulnerabilities of SMEs, it is increasingly evident that these issues are not exclusive to smaller organizations. The SCOUT project experimentally demonstrates that similar challenges—such as resource limitations, knowledge gaps, and fragmented risk awareness—also affect large corporations and national infrastructures responsible for critical services [

25]. Furthermore, some research stresses the need for adaptive, multi-agent decision support systems that can improve information security management across various organizational contexts, while others highlight the systemic risks and interconnected threats facing the EU financial system, calling for a more holistic and risk-based cybersecurity approach [

26,

27].

Despite the growing body of literature, current frameworks—such as those applied in the SME context—often overlook forensic readiness, a crucial component for post-incident analysis, accountability, and the identification of internal failures or personnel-related vulnerabilities. As Sule, D. (2014) outlines, integrating forensic readiness into cybersecurity planning supports both legal compliance and operational resilience [

28]. Addressing this gap could significantly enhance the ROHAN model and similar frameworks, enabling SMEs and larger organizations alike to prepare not only for prevention but also for effective response and recovery. Future research should focus on integrating forensic readiness into scalable cybersecurity strategies that are responsive to evolving threats and organizational diversity.

4. Results and Analysis

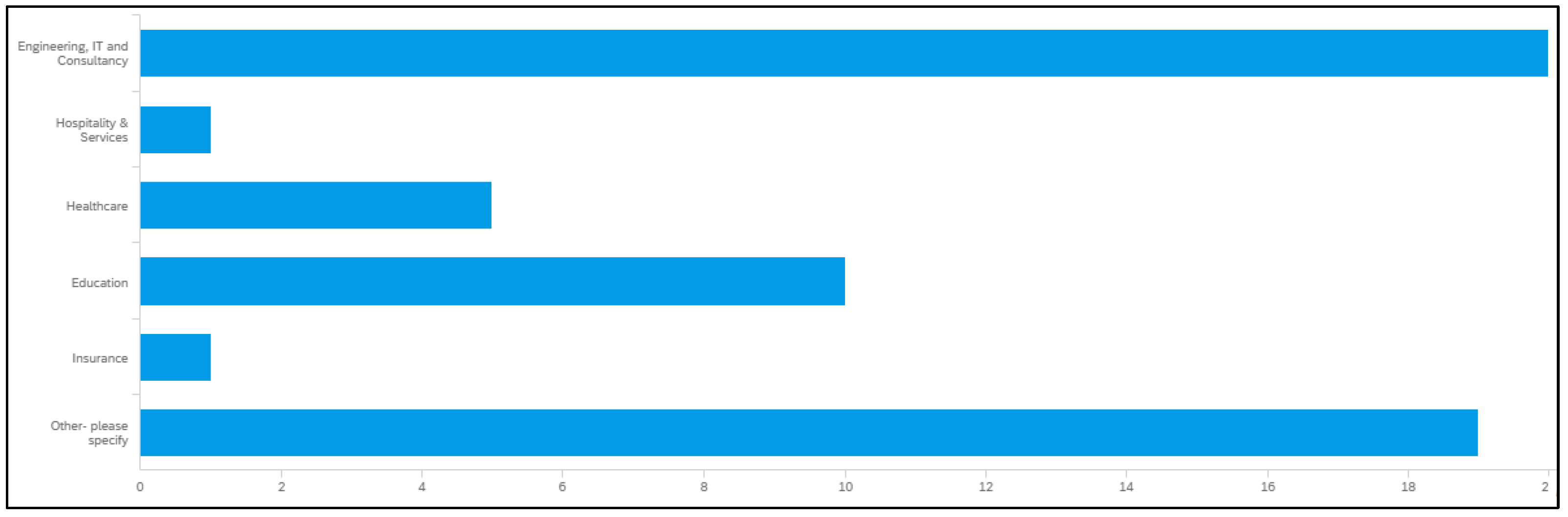

The results below were obtained from the first iteration of data collection sampled across 21 SMEs in Wales back in 2023.

It was observed that “Other—please specify” was the most common category, with 10 entries, as shown in

Figure 4. This suggests that many respondents’ industries did not fit into the predefined initial categories declared. “Engineering, IT, and Consultancy” was the second most common category, with 6 entries. “Healthcare” had 3 entries. “Hospitality and Service” and “Insurance” each had 1 entry. This distribution showed a diverse range of industries in the dataset, with a notable concentration in the “Other” category and the “Engineering, IT, and Consultancy” sector. The high number of “Other” responses indicated that the predefined categories did not fully capture the range of industries represented in the survey.

Extracts from results obtained from the second data collection, sampled across 127 SMEs in Wales back in 2023, were also re-examined. The research data here consisted entirely of categorical variables, which resulted in the inability to use traditional regression analysis models that required numerical data. However, this process unlocked valuable insights by transforming these categorical variables into numerical ones.

The research used the following Encoding Categorical Variables:

One-Hot Encoding: For variables with multiple categories (e.g., color: red, blue, green), the one-hot encoding creates separate binary columns for each category, with a value of 1 indicating membership in that category and 0 otherwise.

Binary Encoding: For yes/no questions, the use of binary encoding, assigning a value of 1 to “yes” and 0 to “no.”

With the categorical variables encoded, the study addressed the issue of potentially high dimensionality in the data using Dimensionality Reduction. This refers to having a large number of features (variables). Here, the research employed the Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA is a technique that reduces the number of dimensions while aiming to capture most of the variance in the data. This simplified analysis and visualization. Once the categorical variables were encoded and PCA performed, the study proceeded with the next steps of analysis. This involved creating a correlation matrix to identify potential relationships between variables and visualizing the data in a lower-dimensional space for better understanding.

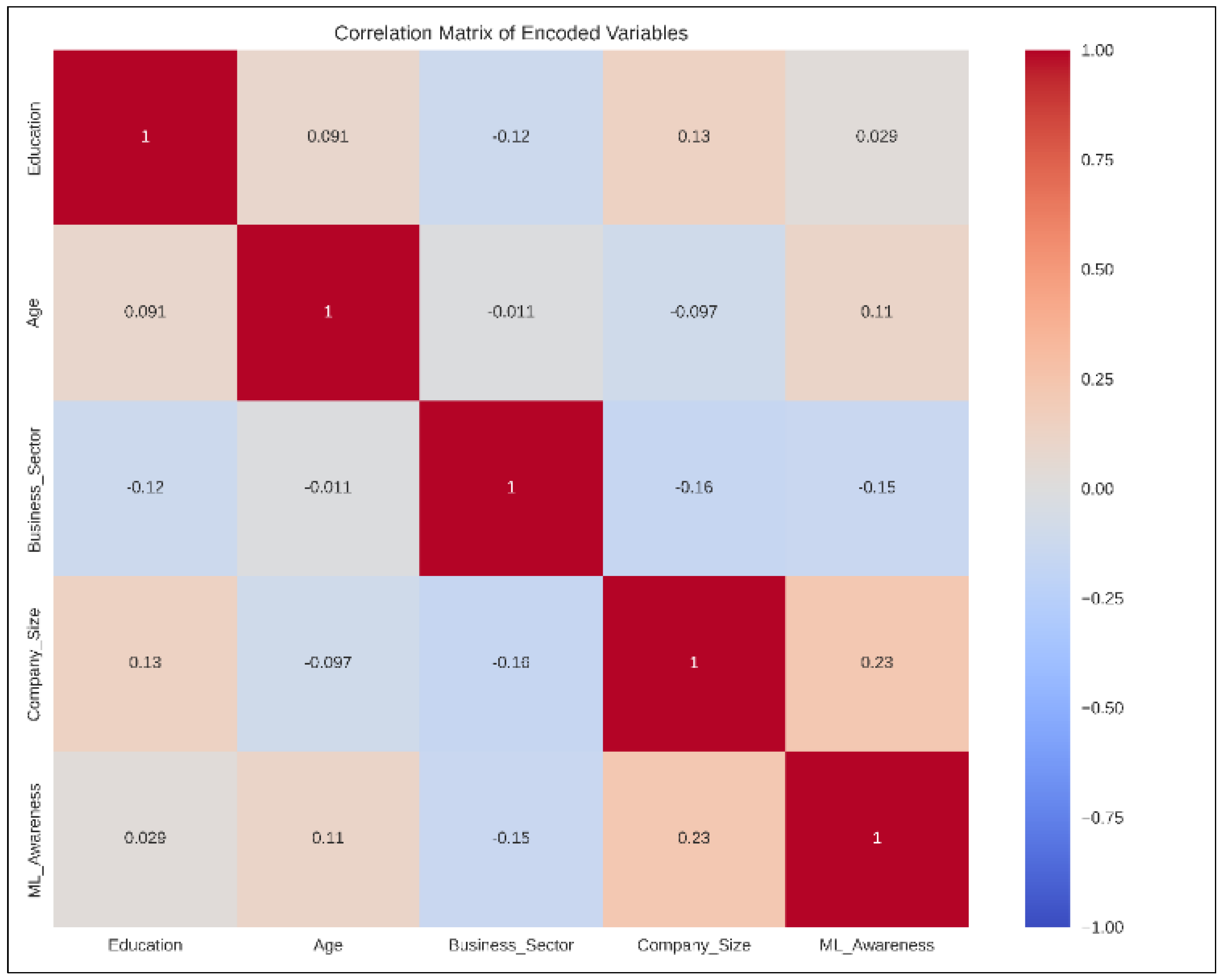

The results of the correlation matrix for the encoded variables are displayed below in

Figure 5:

The analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) yielded some key observations from Dimensionality Reduction:

Capturing the Big Picture: The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) managed to explain roughly 50.24% of the total variation present in the original data. By considering the first five principal components, the study captured 100% of the variance. This exploration of these initial components effectively summarizes the most significant patterns within the data.

Dissecting Feature Importance: Each original feature contributed differently to the newly formed principal components. For instance, the feature “Education” held a greater weight in PC1 and PC3, suggesting its strong influence on the patterns captured by these components. Similarly, “Age” was more prominent in PC2, highlighting its significance in a different underlying trend.

The table represents the first two principal components extracted from the original data. Each row corresponds to an individual data point (e.g., a survey participant), and the values represent the coordinates of that point in this new, lower-dimensional space created by PCA. Think of PC1 and PC2 as new variables derived from combinations of the original features. These combinations were chosen to capture the most significant variations in the data. While they might not directly translate back to the original features started with, they represent the most important underlying trends or patterns within the data.

To gain a clearer understanding of what these principal components (PC) represent and how the data were distributed in this new space, a scatter plot using PC1 and PC2 was created as axes. Additionally, calculating the variance explained by each component helped quantify the amount of information retained after dimensionality reduction. This helped determine if the reduction had significantly compromised the data’s integrity. By analyzing these aspects, the research leveraged PCA as shown in

Figure 6, to gain valuable insights from the data without getting inundated by too many features.

PC4 seemed to represent a contrast between respondents with “A Levels or College” education versus those with “Bachelor’s degrees and professional certifications”. This component might be capturing a dimension related to the level and type of education, particularly distinguishing between vocational and higher academic education.

PC5 appeared to highlight a distinction between those with standalone “professional certifications” and those with a combination of “A Levels/College and professional certifications”. This component might have represented a dimension related to the pathway of professional development, contrasting direct professional certification against a mix of academic and professional qualifications.

This analysis investigated the potential interpretations of principal components (PCs) derived from a dataset on SMEs and their adoption of machine learning (ML) and cybersecurity practices.

The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) may hold information regarding educational attainment variations among survey respondents within the SME sector. Additionally, these components could reflect contrasting approaches to professional development and qualification acquisition within SMEs. PC1 and PC2 might also reveal underlying disparities in how individuals with different educational backgrounds perceive or engage with ML and cybersecurity within their organizations. To gain a more comprehensive understanding, it was crucial to examine the “loadings” associated with other variables in the dataset. Of particular interest were variables directly related to awareness of ML and cybersecurity practices within SMEs. The loadings quantify the contribution of each original feature to the formation of each principal component.

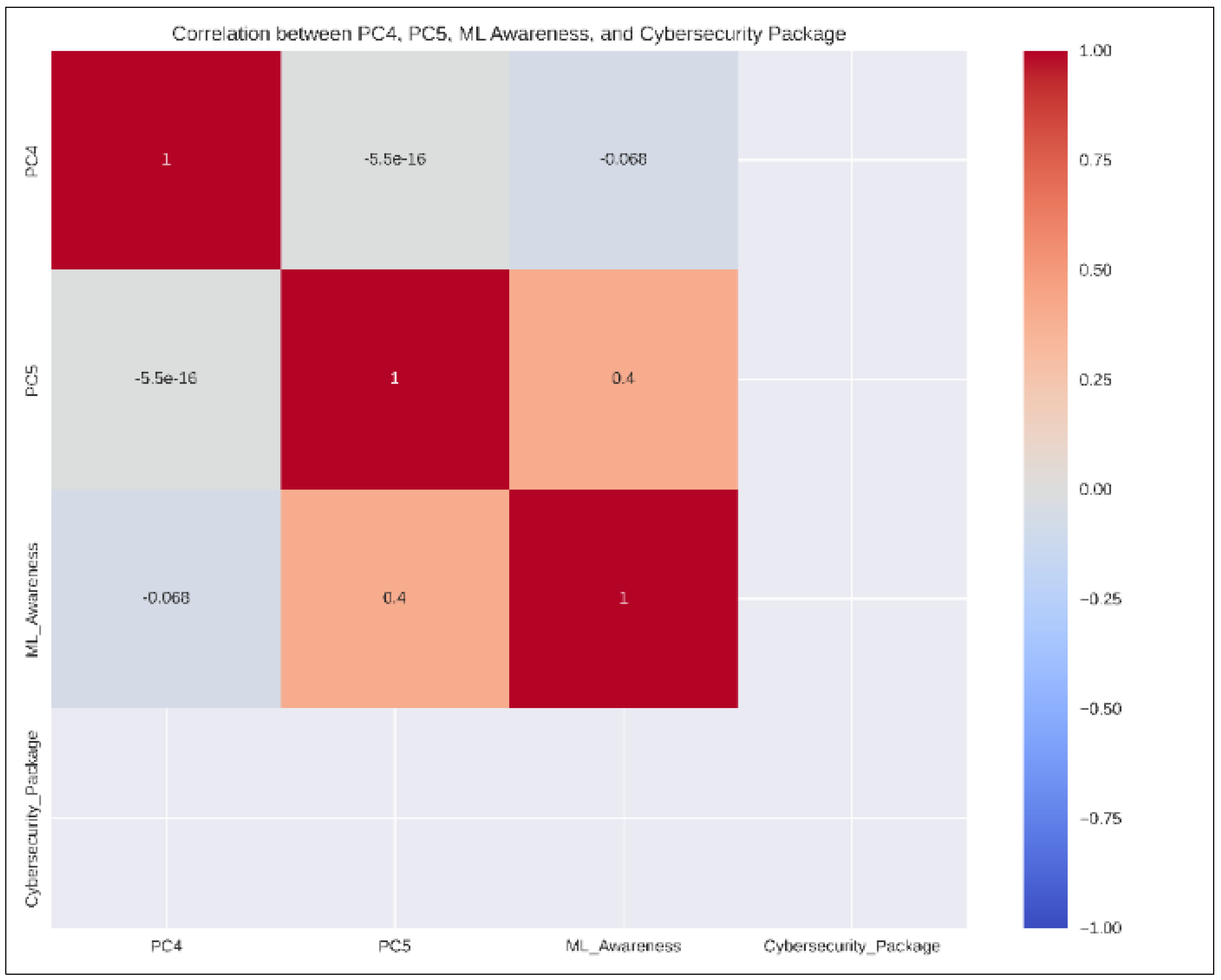

In order to synthesize the investigation of educational background and adoption rates, the inquiry regarding the implications of educational background and professional development (captured by PC4 and PC5) on the adoption of ML and cybersecurity in SMEs is a valuable one. To explore this relationship further, there is a need to analyze the correlation between these components (PC4 and PC5) and relevant variables in the dataset, such as those measuring ML awareness and cybersecurity practices. However, this encountered a data pre-processing challenge. Some text data, likely from columns like “ML_Awareness” and “Cybersecurity_Package,” needed conversion into numerical values for compatibility with PCA. Therefore, the need to address this issue by transforming these categorical variables (e.g., “High Awareness” or “Basic Package”) into numerical representations before proceeding with the correlation matrix calculation proved vital. The correlation matrix ultimately helped elucidate the relationships between these components and other variables within the dataset as shown in

Figure 7.

This section delves into the implications of principal components (PCs) on machine learning (ML) adoption within SMEs. To begin, the relationship between educational background/development and ML awareness is analyzed. An intriguing observation is that the average PC4 and PC5 scores (representing educational background and professional development) for various cybersecurity package choices exhibit values very close to zero. This suggests a potentially weak correlation between these principal components and the selection of cybersecurity packages by SMEs. The key findings in the analyzed data suggest:

Educational Background and ML Awareness: A positive correlation is observed between PC4 (educational background/development) and ML awareness in SMEs. This implies that companies with higher levels of education and professional development personnel are more likely to be aware of, and potentially adopt, ML technologies.

Cybersecurity Packages and the PC Model: The relationship between PC4/PC5 and cybersecurity package adoption remains unclear. This suggests that other factors might hold a greater influence on the cybersecurity choices made by SMEs.

Beyond Education and Development: The overall weak correlations indicate that while educational background and professional development play a role in ML awareness and adoption, they are not the sole determinants for SMEs. Other aspects, such as company size, industry, or specific business needs, might also be significant.

Nuances of Professional Development: The varying PC5 scores across different ML awareness levels suggest that this component might capture some subtle aspects of professional development that have a complex relationship with ML adoption.

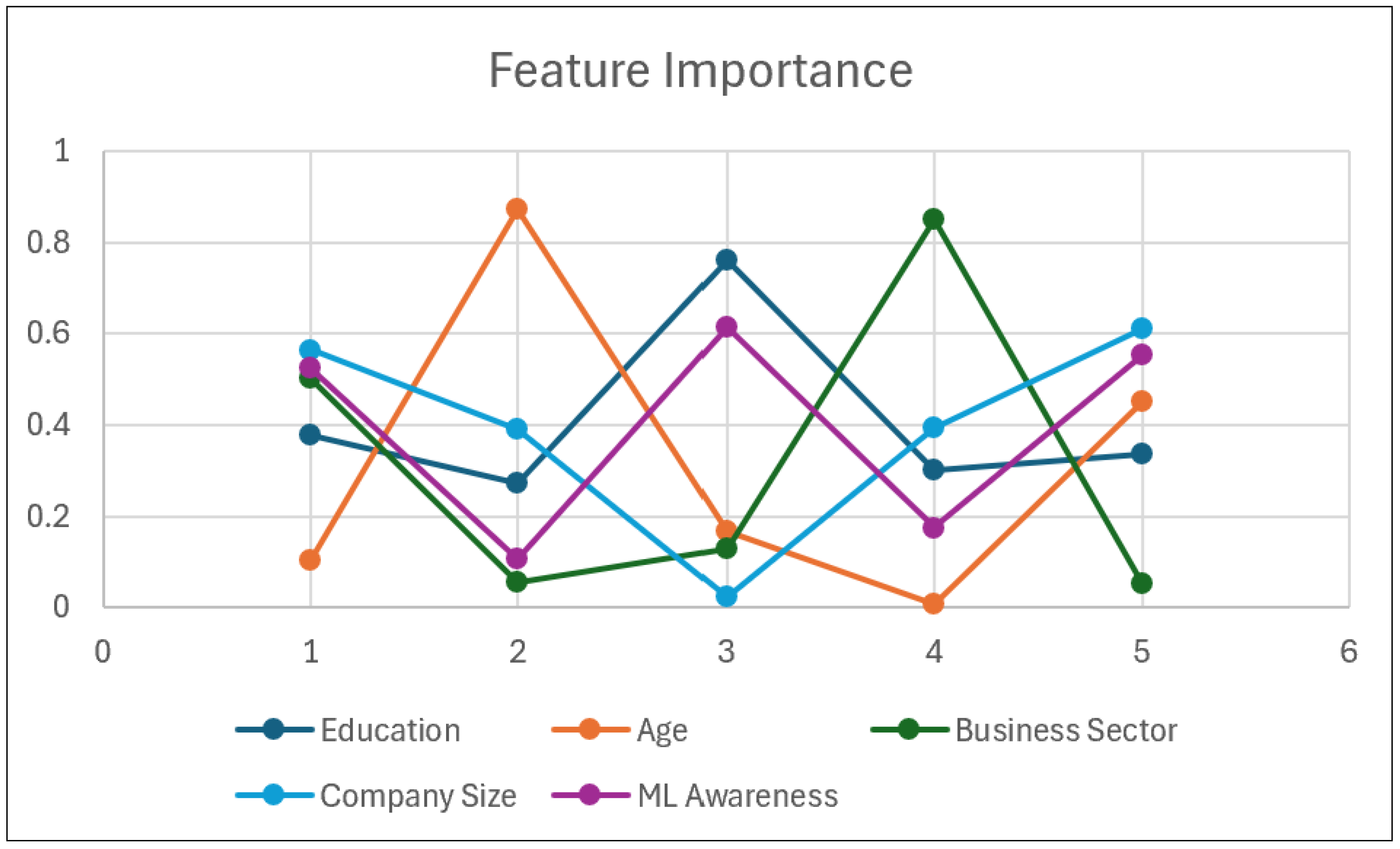

Figure 8 shows that in order to gain further insights, the exploration of the specific variables contributing most heavily to PC4 and PC5 is additionally analyzed using other factors that could influence ML and cybersecurity adoption in SMEs would be beneficial.

Figure 8 continues to explore data on how company characteristics, adaptation rates, company size, industry, and business needs influence ML and cybersecurity adoption in SMEs. To analyze how these factors influence adoption rates, there was a need to examine the relevant data points within our dataset further, specifically focusing on columns related to company size, industry, and business needs. Extracting this information and creating data visualizations will help gain a clearer understanding of these relationships.

In order to further analyze the principal components (PCs), this section explores the results of PCA applied to the dataset, investigating factors influencing machine learning (ML) adoption in SMEs for cybersecurity purposes.

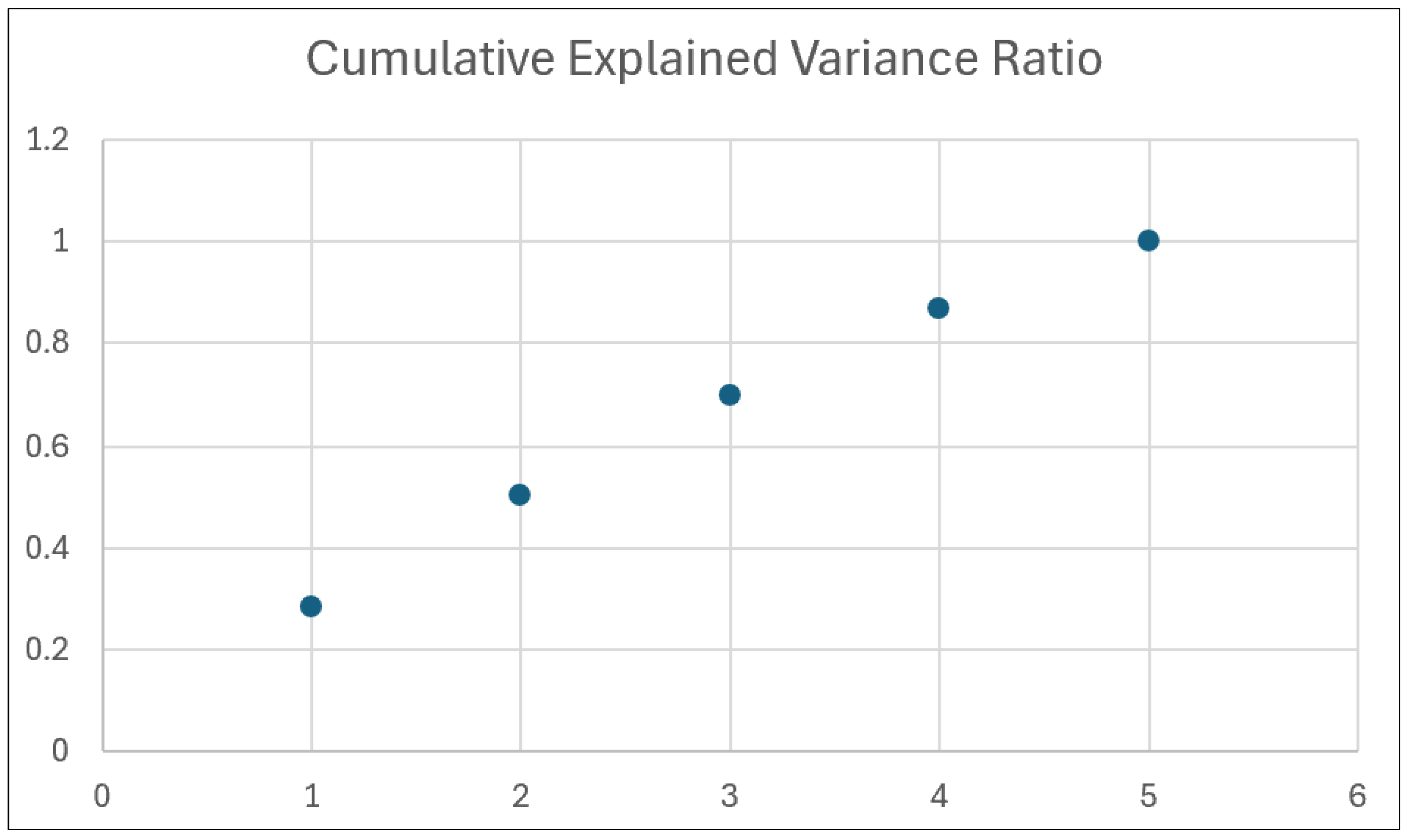

Table 1 shows the Variance Ratio explained cumulatively.

Figure 9 shows the corresponding scatterplot.

Table 2 shows the importance of the features declared in the data sample research.

Figure 10 shows the corresponding scatterplot.

Each row represents a feature (e.g., Education), and each column represents a principal component (PC). The values indicate the contribution of each feature to the corresponding principal component. From these tables, the key observations explained are as follows:

Explained Variance: The first two principal components capture a significant portion (50.24%) of the data’s variance, indicating that these components represent the most important underlying factors. All five components are required to capture the entirety of the data’s variance.

Feature Importance: The “Feature Importance” table reveals how different features contribute to each principal component. For example, “Education” has a high importance in PC1 and PC3, suggesting a strong association with these components. Conversely, “Age” has a high importance in PC2, indicating a distinct influence on this component.

Relating this to the research and the data collected from SMEs through the survey gave reference and showed the following outcome:

Identifying Key Factors: By reducing the data into a few principal components, the study can pinpoint the most critical factors influencing ML awareness and adoption in SMEs. The varying contributions of features (e.g., high importance of “Education” in certain components) highlight their significance.

Data Visualization: Scatter plots utilizing the first two principal components can visually represent the positioning of different SMEs based on their characteristics. This helped identify patterns and potential clusters within the data.

Practical Implications: Policymakers and business leaders can leverage these insights to prioritize factors when promoting ML adoption in cybersecurity for SMEs. Tailored training programs based on factors like age or educational background can be developed to enhance ML awareness.

The PCA analysis condenses the complex data into a manageable number of principal components, facilitating the identification of key factors impacting ML awareness and implementation in SMEs. By focusing on these key factors, the study can develop more effective strategies to promote ML use in cybersecurity advancements.

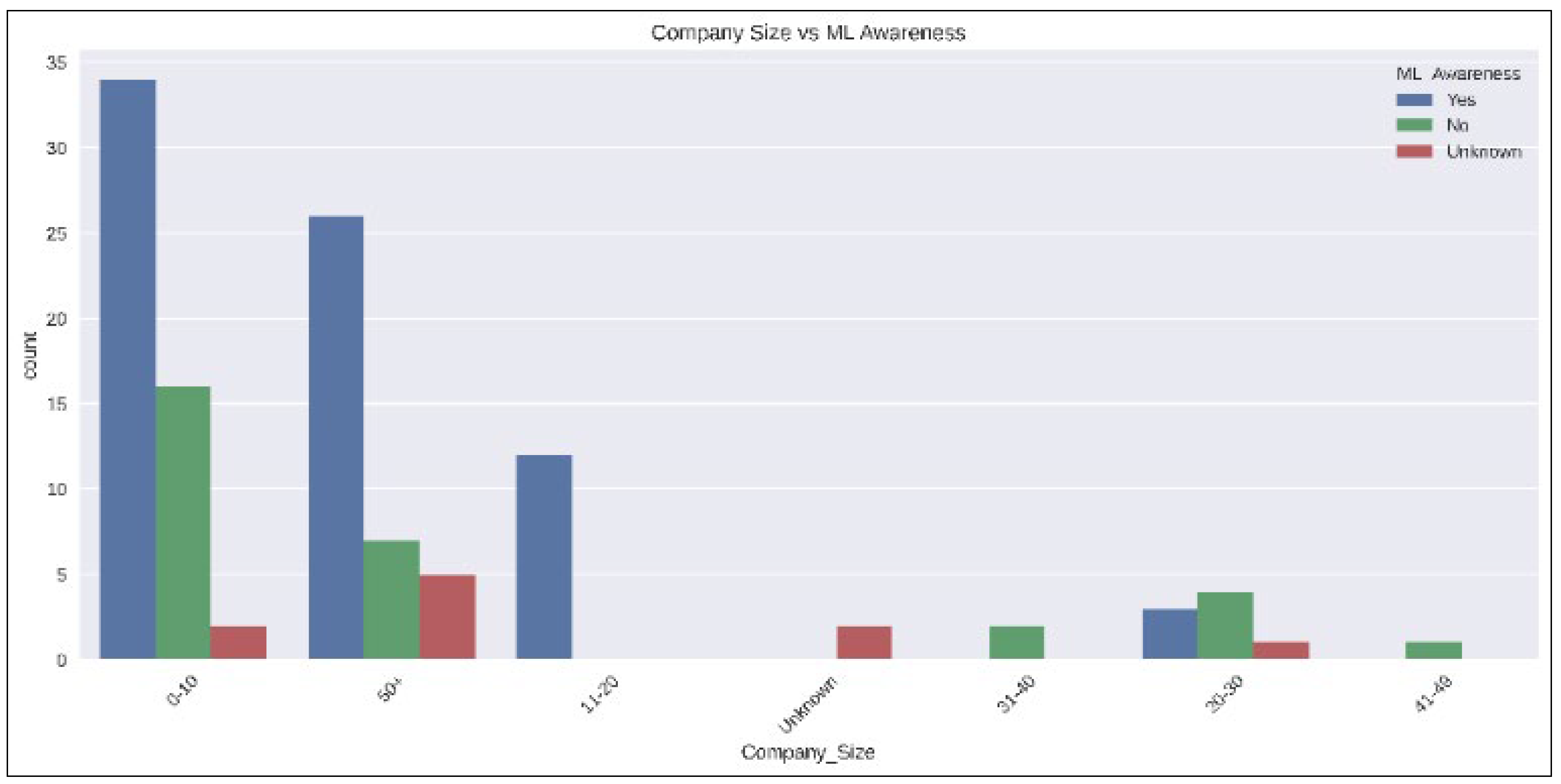

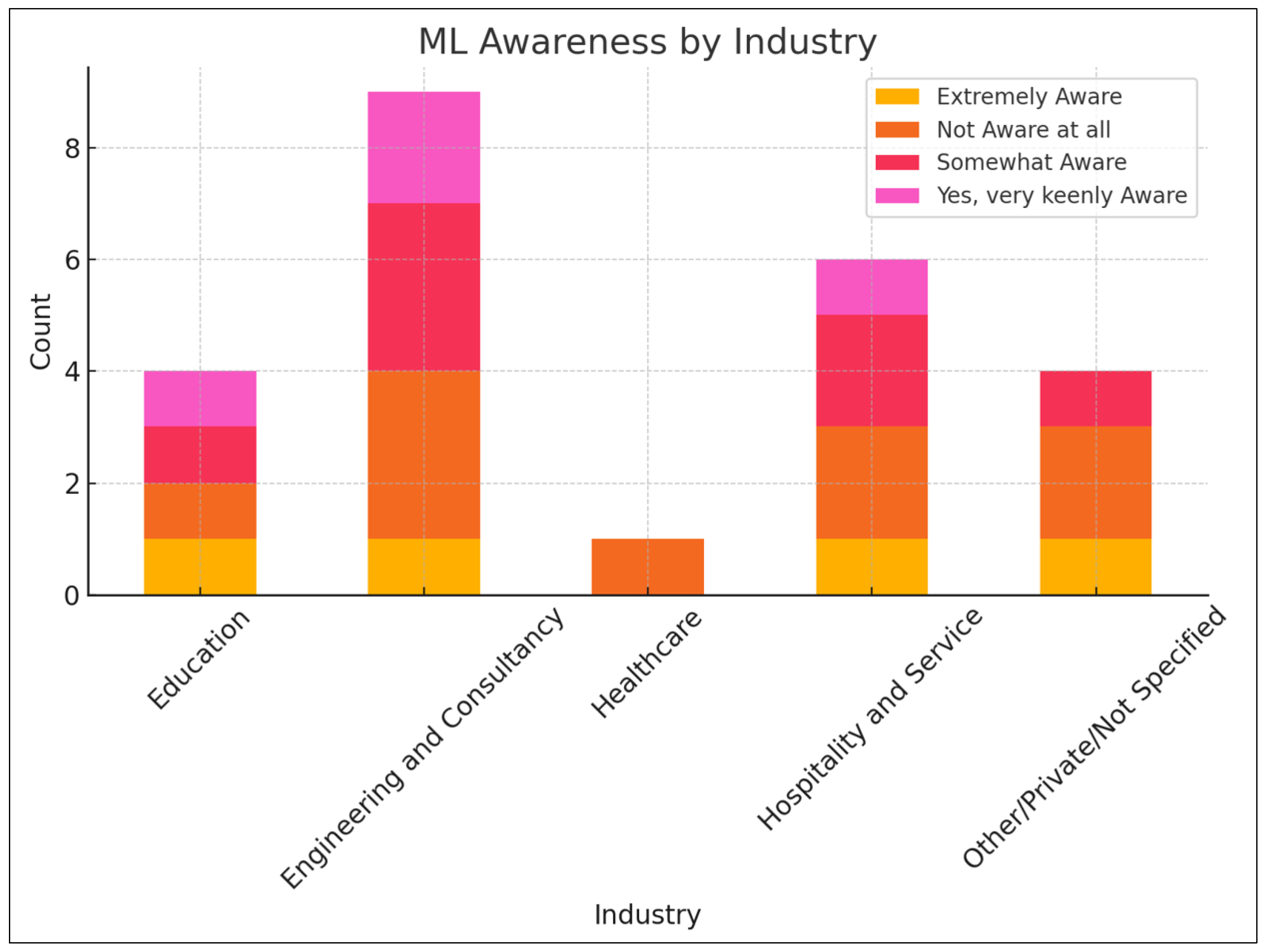

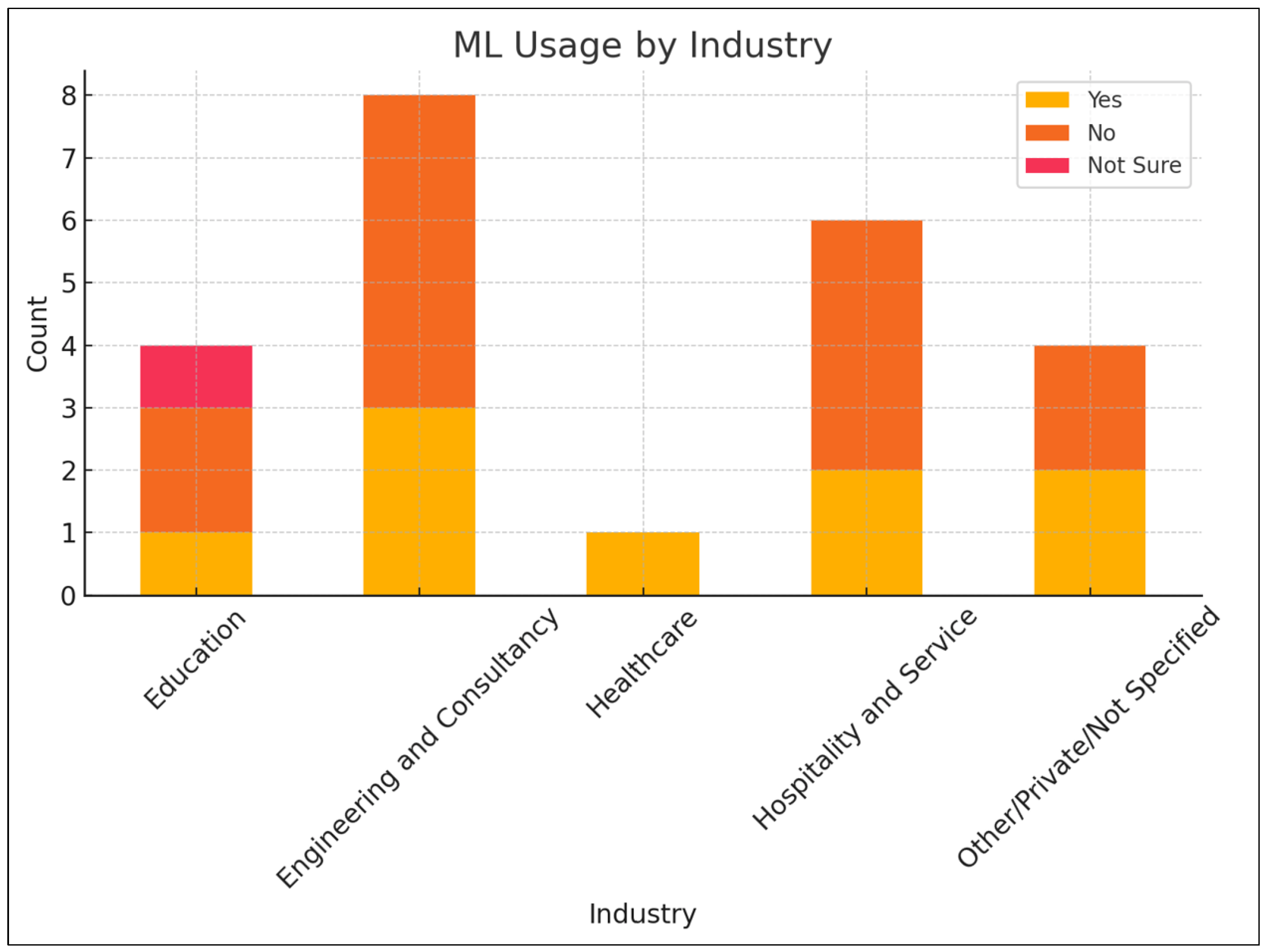

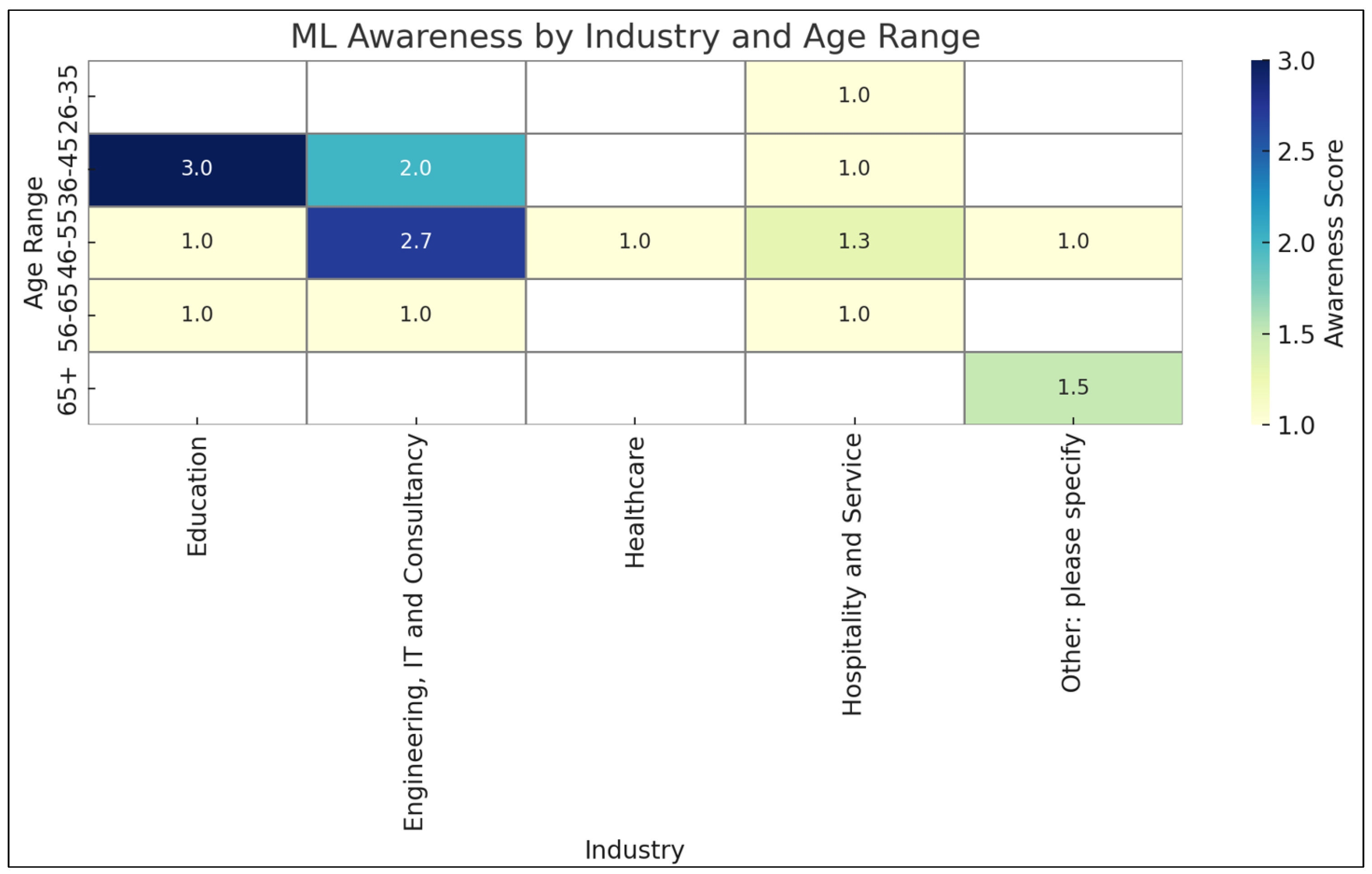

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show variations in the data captured between ML Awareness and Company size and Industry.

Figure 17 shows the box plots providing a summary of the distribution for each encoded variable. They show the median, quartiles, and potential outliers for each variable. From these visualizations, it was observed that the pair plot’s diagonal elements showed that most variables have somewhat uneven distributions, with some having multiple peaks. This suggested that the data were not normally distributed for most variables. The scatter plots in the pair plot did not show strong linear relationships between most variables. This aligned with our earlier observation from the correlation matrix. The box plots revealed that some variables, particularly ‘Education’ and ‘Business_Sector’, had outliers (points beyond the ideals). The encoded variables had different ranges, which was expected due to the encoding process. For example, ‘Education’ seemed to have fewer unique values compared to ‘Business_Sector’.

These visualizations provided a good overview of the data’s structure and relationships. They confirmed that there were no strong linear relationships between variables, which could have impacted the performance of certain machine learning models.

5. Discussion

The study found that while there was a general awareness of cyber threats among SMEs in Wales, the depth of understanding varied significantly. Many SMEs were aware of the existence of threats such as phishing and malware but lacked detailed knowledge about how these threats operated and how they defended against them effectively. This superficial awareness led to a false sense of security. Rawindaran’s (2023) research [

3] paints a nuanced picture of cybersecurity awareness programs for SMEs. While not a silver bullet, the study found these programs to have a positive impact. SMEs that participated in structured training programs exhibited a demonstrably deeper understanding of core cybersecurity principles, according to the literature. This translates to a higher likelihood of implementing essential security measures, such as strong password management practices and regular software updates. However, the effectiveness of these programs was hampered by two key limitations. Their outreach was demonstrably limited. Many SMEs simply did not have access to such training. This could have been due to several factors, including resource constraints, where the cost of training programs was a significant barrier for SMEs with tight budgets. There was also a lack of awareness where some SME owners may not have been aware of the available cybersecurity training programs or their importance. There was a sustainability of knowledge whereby the effectiveness of stand-alone training programs may diminish over time. Without ongoing reinforcement or refresher courses, the knowledge gained from initial training could fade, potentially reducing the long-term impact on cybersecurity posture.

These limitations highlighted the need for a multifaceted approach to cybersecurity awareness in SMEs. While structured training programs offer a valuable foundation, additional strategies are necessary to ensure a more comprehensive and sustainable level of awareness. While the landscape of cybersecurity resources is flourishing, Rawindaran’s (2023) research [

3] exposes a critical gap between availability and implementation for SMEs. Several formidable challenges continue to impede effective cyber defense within these organizations. Again, introducing the same concepts shows the need for repetitive guidance within the SME landscape.

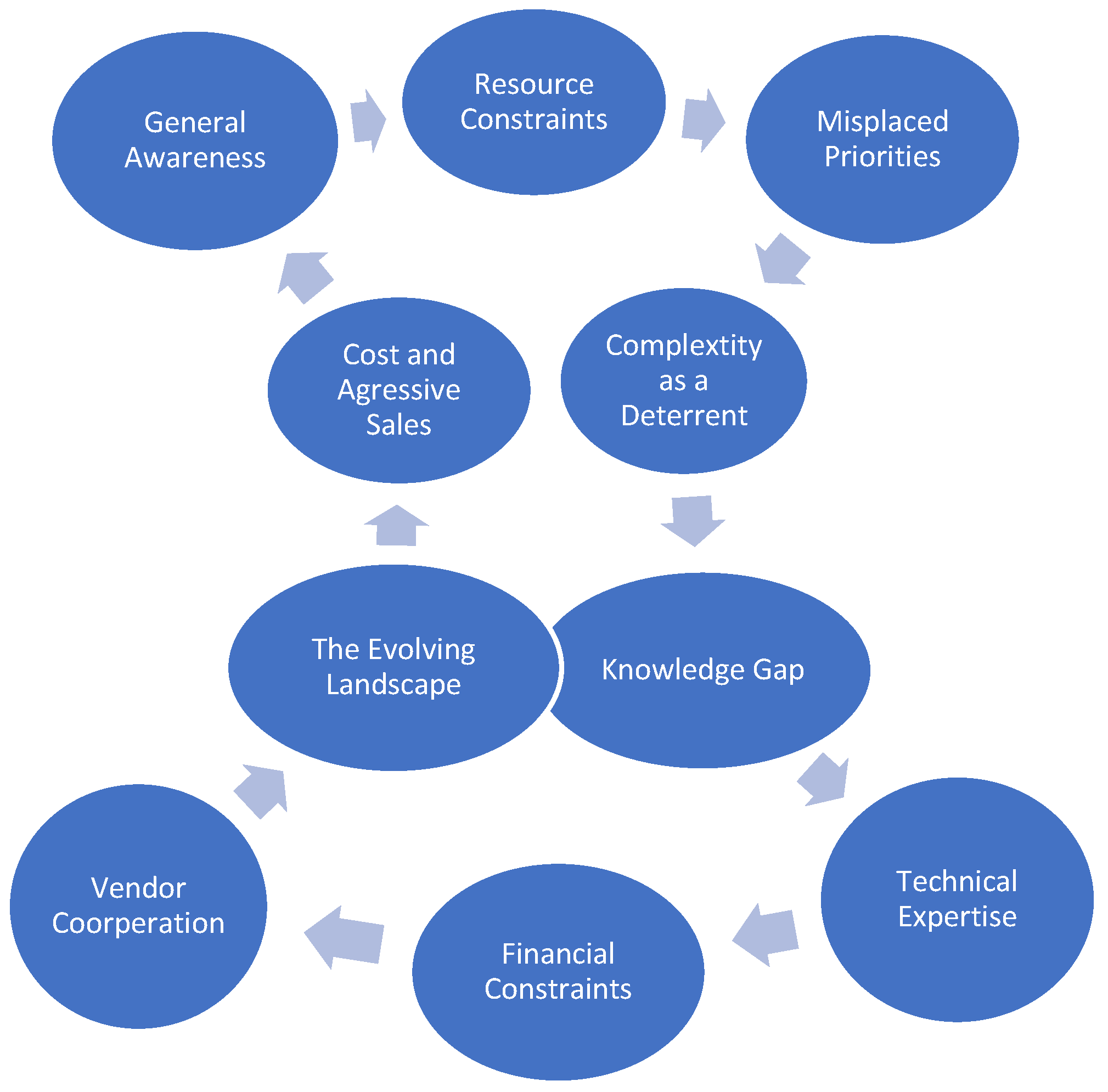

Figure 18 explores the multi-pronged approach for SMEs to digest their digital transformation. The approach starts with Resource Constraints, where many SMEs operate on a tightrope, their budgets leaving little room for investment in cutting-edge security solutions or dedicated IT personnel with the specialized expertise to manage them. This lack of in-house expertise further weakens their defenses. SMEs may struggle to identify and patch vulnerabilities due to a deficit of cybersecurity knowledge among their existing workforce. There is also the notion of “Misplaced Priorities”, where there is a compounding problem of the perception among some SME owners that cybersecurity is a distant threat, not a critical business concern. This perception often stems from a lack of firsthand experience with major cyberattacks. This misplaced sense of security can lead them to prioritize other areas of investment, downplaying the very real risks posed by cyber threats. “Complexity as a Deterrent” is the perceived complexity of implementing cybersecurity measures that can be a significant deterrent. The technical jargon of cybersecurity protocols can discourage SMEs from taking the necessary steps to safeguard their businesses. Interestingly, the field of cybersecurity is increasingly turning to AI and ML as a potential solution to these challenges faced by SMEs. However, implementing ML for cybersecurity presents its own set of hurdles. The knowledge gap exists whereby some companies, especially SMEs, lack a basic understanding of ML and its applications in cybersecurity. They often rely on outsourcing their IT security needs to experts. Technical expertise tends to lean towards traditional cybersecurity solutions, and SMEs often lack the in-house technical expertise required to implement and maintain ML-based solutions. There exist financial constraints that make the cost of implementing and maintaining ML-based solutions financially challenging for some SMEs. There is also a need for third-party vendor cooperation, and a lack of cooperation from these vendors selling ML-based solutions can create additional barriers. The evolving threat landscape is one of the biggest challenges in the constantly innovating threat landscape. Attackers develop new methods of intrusion that may not follow patterns detectable by current ML algorithms. Cost and aggressive sales highlight the high cost of ML-based solutions, coupled with aggressive sales tactics from vendors, which can further discourage SMEs from adopting them. Last but not least, is the general awareness or lack of awareness about the potential benefits of using ML for cybersecurity among some SMEs.

These challenges highlight the need for a multi-pronged approach. Better education and awareness programs can empower SMEs to understand the benefits of both traditional and ML-based cybersecurity solutions. Financial support programs and government initiatives can help SMEs overcome resource constraints. Finally, fostering greater vendor cooperation and developing user-friendly interfaces for ML-based solutions can make them more accessible to SMEs. By addressing these challenges, we can bridge the gap between the growing landscape of cybersecurity resources and the ability of SMEs to effectively implement them, ultimately creating a more secure digital environment for all.

The escalating prominence of cybersecurity threats has fueled the commercialization of various tools and programs aimed at boosting awareness among organizations. Numerous entities are actively developing and profiting from educational platforms, training modules, and tailored awareness campaigns specifically designed for SMEs. Commercially driven training companies can exemplify this trend by offering comprehensive cybersecurity awareness training that can be customized to the specific needs of smaller businesses. These scalable and accessible programs allow SMEs to improve their cybersecurity posture without incurring significant expenses in infrastructure or personnel.

The monetization of cybersecurity awareness extends beyond training materials. Specialized software solutions are being developed to automate security training and simulate phishing attacks. These software solutions help businesses test and solidify their employees’ awareness and response capabilities. As previous research highlighted, the commercial sector’s involvement in cybersecurity training has significantly bolstered the availability and quality of resources for SMEs.

Rawindaran’s (2023) research [

3] underscores the critical need for more targeted and accessible cybersecurity awareness programs specifically tailored to the unique needs and limitations of SMEs. Some key recommendations to address this could include the following:

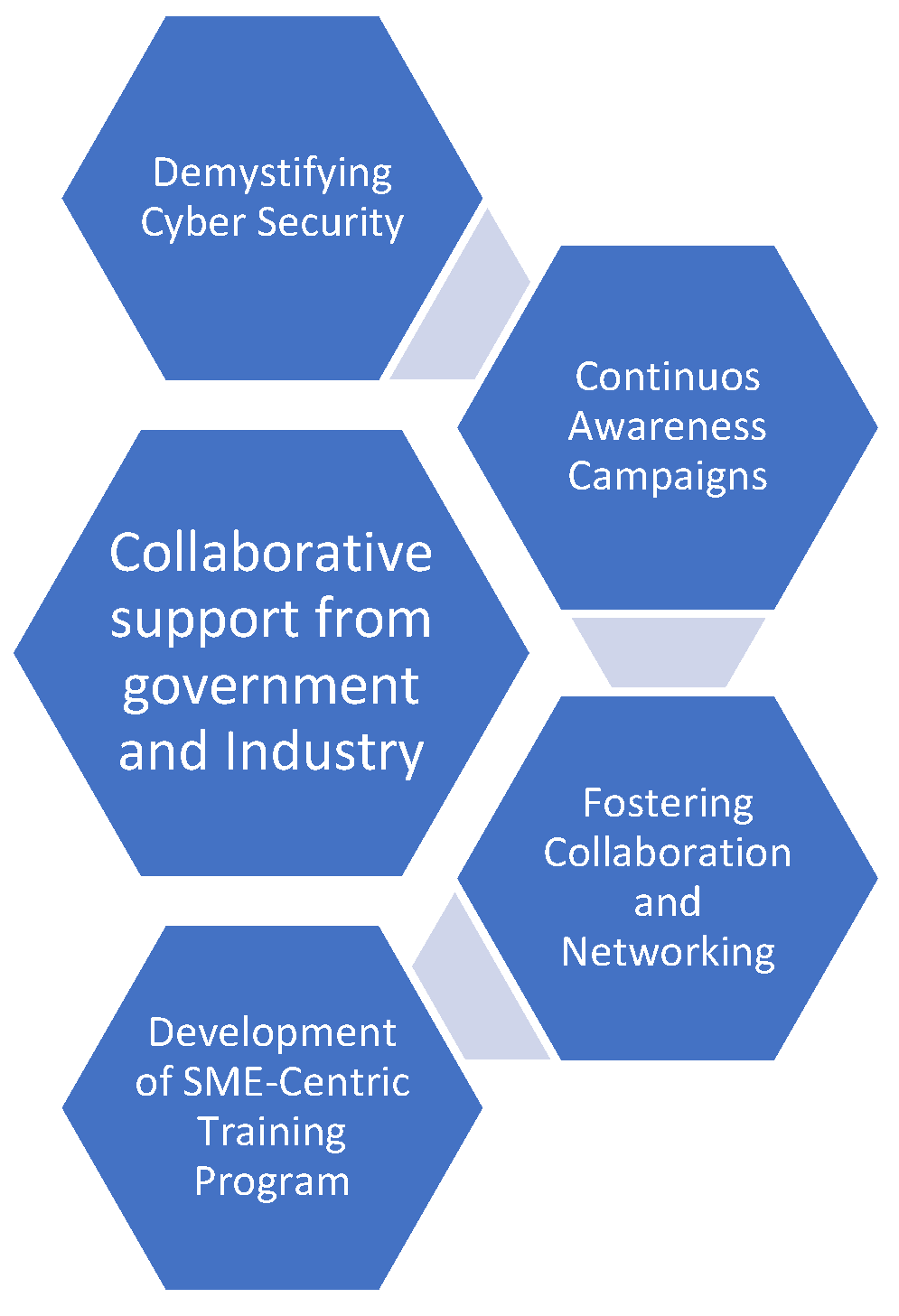

Figure 19 further advocates recommendations for SMEs to be able to develop an SME-Centric Training Program, which is meticulously crafted to address the distinct challenges faced by SMEs. Accessibility is paramount, with online platforms being a prime delivery method. Collaborative support from the Government and Industry could subsidize training costs and provide SMEs with readily available resources. Simplifying the language and concepts used in cybersecurity training enhances information accessibility for non-experts within SMEs. Additionally, continuous awareness campaigns could be the answer to keeping SME owners and employees informed about the ever-evolving cyber threat landscape and the paramount importance of cybersecurity. This can be further continued by encouraging collaboration and fostering networking opportunities among SMEs, which can significantly improve the overall cybersecurity posture of the SME community by facilitating the exchange of best practices and resources.

These recommendations, coupled with the growing focus on cybersecurity awareness within the commercial sector, offer a promising path toward enhancing the cyber resilience of SMEs.

To contextualize the proposed ROHAN model and Cyber Guardian Framework (CGF), it is essential to compare them with existing cybersecurity models widely adopted in SMEs and larger enterprises. Frameworks such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, ISO/IEC 27001, and the Cyber Essentials Scheme (UK) provide foundational structures for information security management, yet often lack the granular customization necessary for SME environments. Unlike NIST and ISO standards—which are comprehensive but resource-intensive—the ROHAN model prioritizes accessibility, modularity, and contextual awareness tailored specifically to the constraints of SMEs. Similarly, while the Cyber Essentials Scheme offers a checklist-based approach for basic protection, it does not provide the in-depth, role-specific educational component or AI-driven risk assessment tools integrated into the ROHAN and CGF frameworks. By combining structured guidance with adaptability, these new models aim to fill a critical gap in the current landscape—delivering a scalable, affordable, and human-centric approach to cybersecurity. This comparative positioning underscores the unique contribution of the study and highlights how the ROHAN model complements, rather than replaces, more standardized approaches by providing SMEs with a viable on-ramp to greater cybersecurity maturity.

6. Future Works

In order to empower SMEs with cybersecurity resilience, this study recommends an improvement on the existing ROHAN model that builds upon the original concept while addressing the specific needs and challenges faced by SMEs. It prioritizes a risk-based approach and emphasizes affordable solutions and employee education.

The new ROHAN model uses the following core principles to integrate risk-based approaches focusing on identifying and prioritizing cybersecurity threats relevant to the SME’s industry, size, and data sensitivity. This aligns with research highlighting the importance of understanding SME-specific needs. It also highlights an employee-centric that integrates a new framework called the Cyber Guardian Framework (CGF) to cultivate a culture of cybersecurity ownership among employees through engaging and accessible training. This directly incorporates research on effective training strategies for non-technical audiences. The new model also highlights cost-consciousness that prioritizes cost-effective solutions based on identified risks. Activities include utilizing free or low-cost resources like government initiatives and open-source tools, reflecting the resource limitations of SMEs. This holistic approach integrates cybersecurity across all functions (IT, HR, Finance) while considering resource constraints. It encourages the exploration of collaboration with industry partners for knowledge sharing and leveraging affordable tools.

The new ROHAN model components will now consist of the following:

R—Readiness (Risk-Based):

Assess cybersecurity risks through vulnerability scans and risk assessments. Being able to identify critical assets and data requiring protection. Being able to develop a cybersecurity policy outlining acceptable behavior and incident response protocols.

O—Ongoing Awareness (Employee-Centric):

Implement a Cyber Guardian-inspired training program for employee education. Being able to conduct regular phishing simulations to test awareness and preparedness. Being able to also foster a culture of cyber vigilance by encouraging employees to report suspicious activities.

H—Holistic Approach:

Integrate cybersecurity measures across all business functions. To explore collaboration with industry partners for knowledge sharing. To be able to consider partnering with cybersecurity service providers for ongoing monitoring and support (optional).

A—Affordability (Cost-Conscious):

Utilize free or low-cost cybersecurity resources. Being able to prioritize training and implement affordable solutions based on identified risks. Be able to explore cost-sharing options with industry partners or government programs.

N—Network Security (Assessment):

Implement basic network security measures like firewalls and strong authentication protocols. Being able to conduct regular software updates and vulnerability assessments/penetration testing. This combines aspects of assessment and network security from the original model, emphasizing ongoing evaluation.

By adapting the original ROHAN model and incorporating research on SME cybersecurity awareness, the new ROHAN model offers a more practical and effective framework for SMEs to build robust cybersecurity strategies. It empowers employees, prioritizes affordability, and ensures a holistic approach tailored to the specific needs of smaller organizations.

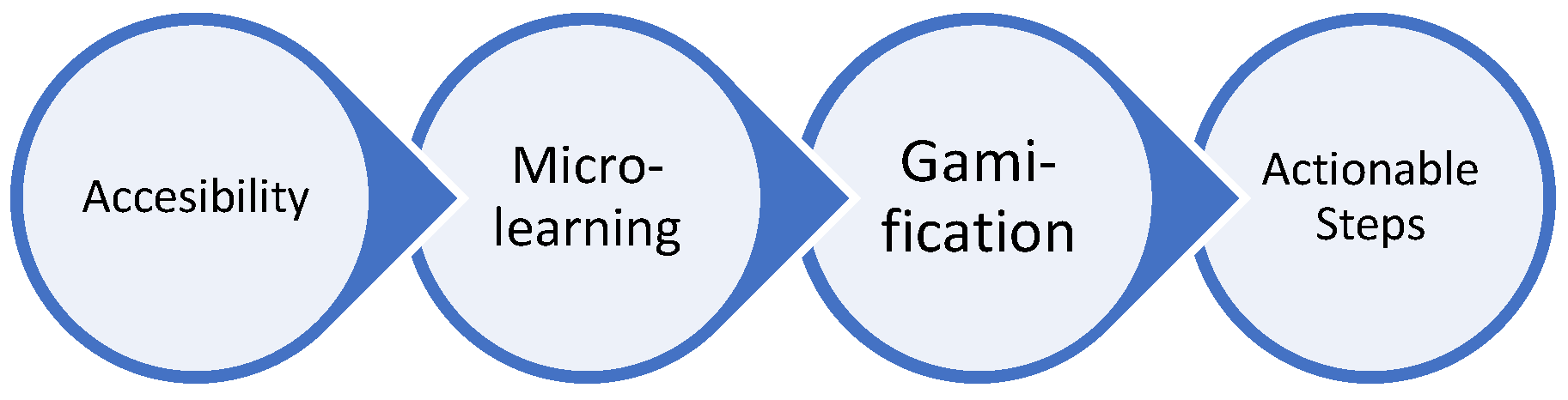

The framework that complements the enhanced ROHAN model is future research in SME cybersecurity awareness training through the exploration of the development and implementation of the CGF. This framework addresses the limitations of existing models by prioritizing accessibility, microlearning, gamification, and actionable steps. Designed for non-technical users, the CGF utilizes clear language, engaging visuals, and bite-sized learning modules to fit busy schedules. Gamification elements enhance engagement and knowledge retention, while the emphasis on practical steps empowers individuals to improve their cybersecurity posture in everyday work. Evaluating the effectiveness of the CGF in real-world SME settings could provide valuable insights for future training program development.

The CGF core principles are shown in

Figure 20.

The core principles of CGF explain that “Accessibility” is designed for non-technical users, utilizing clear language and engaging visuals. The introduction of “Microlearning” creates bite-sized learning modules that can be completed in short bursts to fit busy schedules. The concept of “Gamification” incorporates gamification elements like points, badges, and leaderboards to enhance engagement and knowledge retention. Last but not least, “Actionable Steps” emphasizes practical steps individuals can take to improve their cybersecurity posture in everyday work.

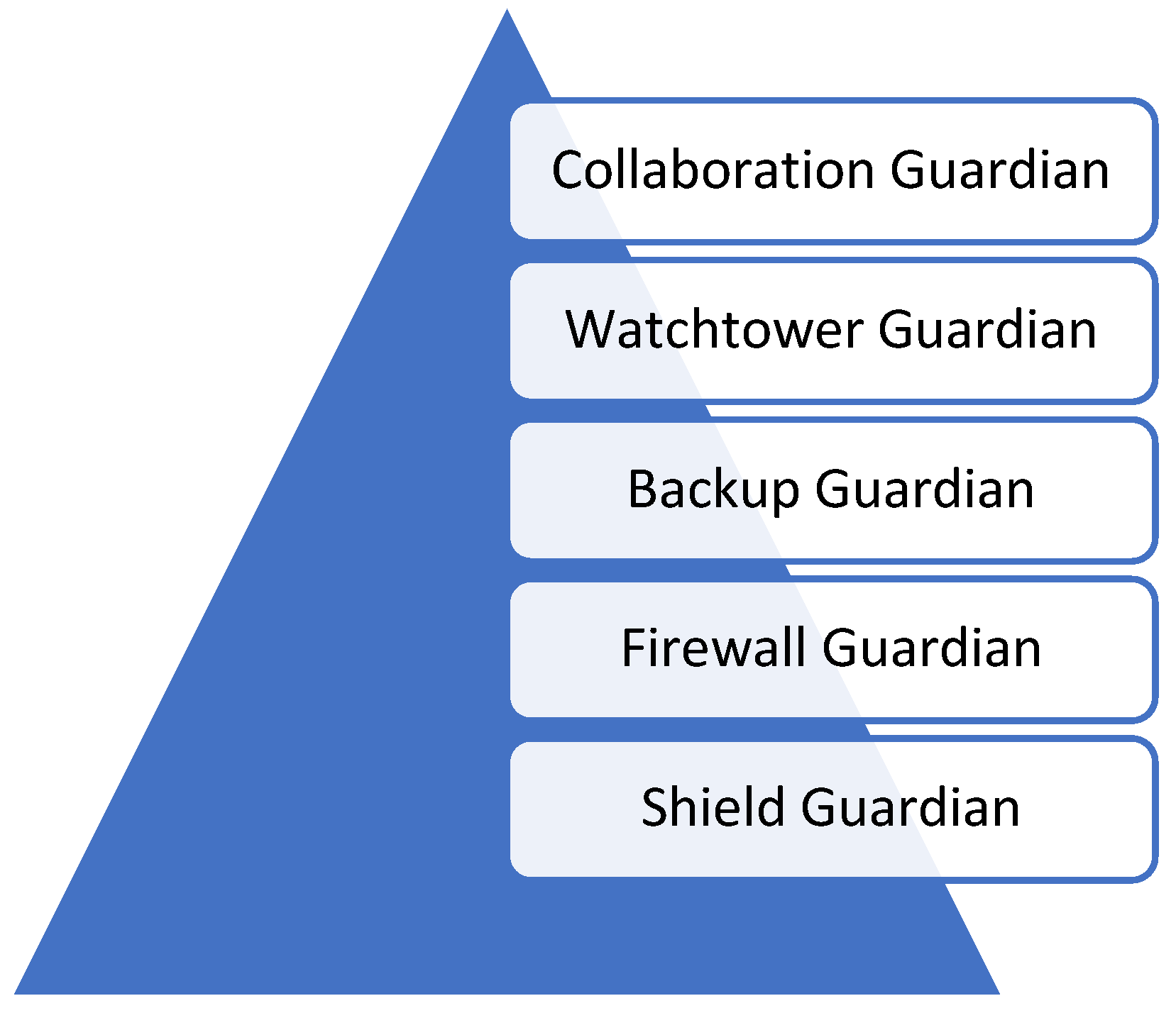

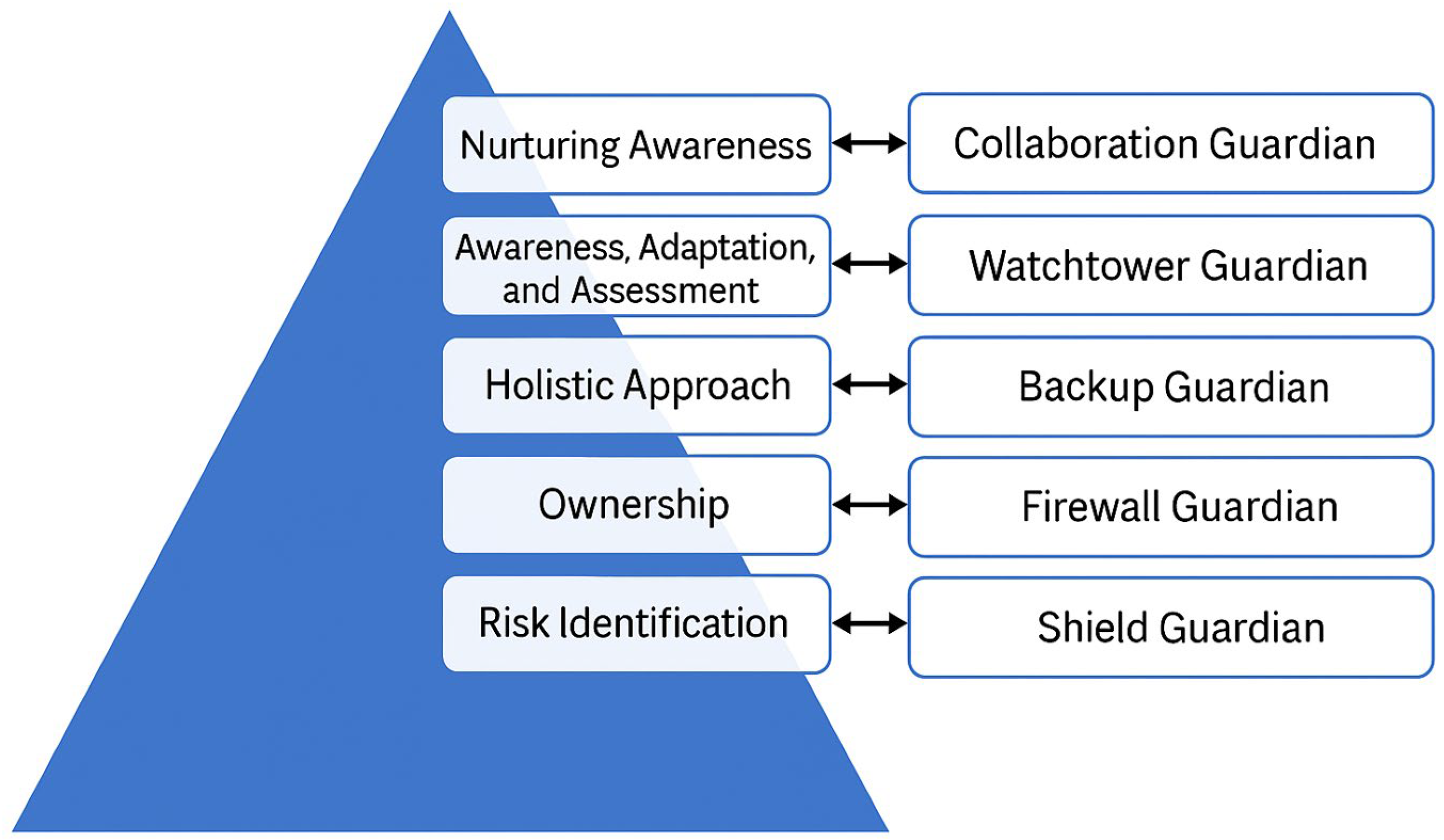

The framework structure of the CGF further drills down into five key pillars, each represented by a distinct “Cyber Guardian”, as follows:

Shield Guardian: Focuses on foundational cybersecurity concepts like identifying phishing attempts, password hygiene, and data security best practices.

Firewall Guardian: Teaches basic threat detection and prevention techniques, including recognizing malware and suspicious activities.

Backup Guardian: Emphasizes the importance of data backups and disaster recovery plans.

Watchtower Guardian: Encourages vigilance and reporting suspicious activities or security breaches within the organization.

Collaboration Guardian: Promotes knowledge sharing and collaboration among employees to enhance overall cybersecurity awareness.

The framework in

Figure 18 can be implemented through various channels such as online platforms, mobile apps, and interactive workshops. SMEs can eventually see the benefits through improved cybersecurity awareness and be equipped with essential cybersecurity knowledge and best practices. They can also reduce the risk of cyberattacks and empower employees to identify and mitigate potential cyber threats. This framework can enhance data security and promote employee behavior that helps safeguard sensitive company data. This then leads to increased employee engagement using techniques such as gamification elements and interactive content, enhancing employee engagement with cybersecurity training.

The new ROHAN model and the CGF could work together seamlessly to address cybersecurity in SMEs. Their integration proposal will work for both frameworks and models and will give clear guidance, as shown below:

Risk Assessment (ROHAN—R): During the initial risk assessment (part of ROHAN’s Readiness), the specific cybersecurity needs and vulnerabilities of the SME are identified.

Tailored Training (CGF): Based on the risk assessment findings, the CGF can be customized to address the most relevant cybersecurity threats and knowledge gaps for the SME’s employees. For example, if phishing attacks are identified as a high risk, the training program might include modules focused on identifying phishing emails and best practices for responding to them.

Delivery and Gamification (CGF): The CGF utilizes microlearning modules, gamification elements, and clear language to deliver engaging and accessible training content that caters to non-technical users.

Ongoing Evaluation (ROHAN—O): The ROHAN model emphasizes ongoing awareness (O). This can include conducting regular phishing simulations after training using the CGF to test employee preparedness and identify areas for improvement in the training program.

Continuous Improvement: Both the ROHAN model and the CGF are designed to be adaptable and evolving. As new cybersecurity threats emerge or employee needs change, the framework and training program can be updated to maintain effectiveness.

The combination of both models and frameworks brings benefits of integration, as shown in

Figure 22, to show the extension of the CGF, showing interactions with the ROHAN model.

Targeted Training: The CGF personalizes employee education based on the specific risks identified through the ROHAN model.

Engaged Employees: The engaging approach of the CGF keeps employees interested and improves knowledge retention.

Actionable Steps: Both frameworks emphasize practical steps individuals can take to improve their cybersecurity posture.

Holistic Approach: Together, they address both technical and human aspects of cybersecurity within the broader framework of the ROHAN model.

By combining the structured approach of the ROHAN model with the practical and engaging delivery methods of the CGF, SMEs can create a more comprehensive and effective cybersecurity strategy that empowers their employees. The combination will be modern and action-oriented towards SME cybersecurity needs.