Abstract

The Internet has become the primary vehicle for doing almost everything online, and smartphones are needed for almost everyone to live their daily lives. As a result, cybersecurity is a top priority in today’s world. As Internet usage has grown exponentially with billions of users and the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, cybersecurity has become a cat-and-mouse game between attackers and defenders. Cyberattacks on systems are commonplace, and defense mechanisms are continually updated to prevent them. Based on a literature review of cybersecurity vulnerabilities, attacks, and preventive measures, we find that cybersecurity problems are rooted in computer system architectures, operating systems, network protocols, design options, heterogeneity, complexity, evolution, open systems, open-source software vulnerabilities, user convenience, ease of Internet access, global users, advertisements, business needs, and the global market. We investigate common cybersecurity vulnerabilities and find that the bare machine computing (BMC) paradigm is a possible solution to address and eliminate their root causes at many levels. We study 22 common cyberattacks, identify their root causes, and investigate preventive mechanisms currently used to address them. We compare conventional and bare machine characteristics and evaluate the BMC paradigm and its applications with respect to these attacks. Our study finds that BMC applications are resilient to most cyberattacks, except for a few physical attacks. We also find that BMC applications have inherent security at all computer and information system levels. Further research is needed to validate the security strengths of BMC systems and applications.

1. Introduction

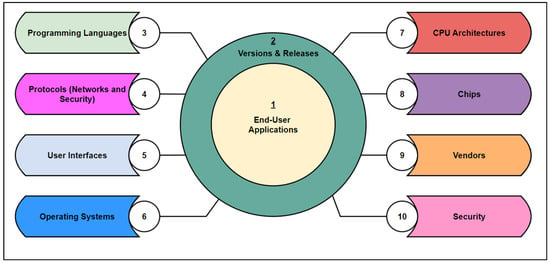

Cybersecurity has become a national and global problem due to globalization and billions of users (5.3 billion) on the Internet [1]. Also, the proliferation of IoT devices on the Internet has introduced new challenges for cybersecurity. There is a veritable ocean of information concerning cybersecurity spanning across many disciplines and systems. Cyberattacks impact all layers of computing and information, including hardware, software, firmware, applications, policies, and other system components. The three dimensions of cybersecurity consisting of information states (storage, processing, and transmission), security principles (confidentiality, integrity, and availability), and countermeasures (policies and practices, technologies, and users) [2] can be extended to ten dimensions, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Ten dimensions of cybersecurity space.

There are many permutations and combinations of this ten-dimensional space. Many releases and versions {2} apply to all other nine dimensions during evolution. Many end-user applications {1} meet user requirements in many areas. Depending on their domains, these end-user applications may be implemented in various computer programming languages {3}. A given end-user application may use a variety of networks and protocols {4} and user interfaces {5}. Most end-user applications run on top of some operating system (OS) {6}, and all computing systems run on some processor architecture such as Intel, AMD, and RISC {7}. Many processor chips exist {8} with multiple cores and other features. There are also many vendors {9} for software, hardware, and other components. Furthermore, there are a variety of cybersecurity methodologies, computer architectures, and implementations {10}. There is heterogeneity and redundancy in the above dimensions and rapid obsolescence. The ever-changing hardware, software, and related products contribute to increased complexity and related cybersecurity issues [3] in computer and information systems, resulting in a waste of resources and human skills, recurring costs, dumping of hardware, and reinventions in many dimensions. The attributes discussed here are mainly due to obsoleting products before their life span [4]. Surprisingly, many other aspects of obsolescence, including planned obsolescence [5,6,7], focus on sustained revenues and profits for the industry. Microprocessor and OS obsolescence are the main contributors to fast changes in computing and information systems.

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities are rooted in many dimensions and layers. Given the multidimensional nature of cybersecurity, it is possible to reduce this space by eliminating some of the dimensions. We present a radical solution that eliminates the OS. When the OS is eliminated, computing is based on the bare machine computing (BMC) paradigm, and applications become BMC applications, as discussed in Section 3 below. This paradigm makes computing devices bare and is inherently secure by design.

Some background on cyberattacks is necessary before discussing our methods to evaluate the BMC paradigm. We have chosen 22 cyberattacks to investigate in our study. In general, an attack always uses one or more vulnerabilities to create an attack. For example, a buffer overflow vulnerability can be used to craft many different types of attacks. Similarly, SQL injection may be used to attack a database system.

- Buffer Overflow: A buffer overflow is a condition that exists when a program can put more data in the buffer than its allocated size. According to [8], “buffer overflow attacks played a major role in the propagation of malicious worms from machine to machine”.

- Phishing: This is one of the most used attacks in the cybersecurity world. Social engineering techniques are mostly used in phishing attacks [9]. Attackers persuade or lure users to share private information that can be used later to exploit their personal accounts, such as banking, credit cards, social security information, and personal assets. They can also use this information to damage their computer system.

- Ransomware: Ransomware is malware that captures the victim’s data or device and renders it unusable till some ransom amount is paid. There are two types of ransomwares: locker and cryptographic [10]. Locker ransomware is intended to lock computer access to users or delete files. Cryptographic ransomware encrypts files with hacker keys and demands a ransom to recover files. The main goal of ransomware is to extort money from victims.

- Denial of Service (DoS): DoS [11] is an attack that can flood a victim’s server with a variety of packets, such as UDP, SYN, HTTP, and ICMP. The goal is to slow down or crash the machine completely. The same attack can be carried out on a server using distributed systems known as distributed denial of service (DDoS) [11] to accomplish a larger and faster attack on a victim.

- Man in the Middle (MitM): MitM [12] involves an attacker successfully inserting themselves between two communicating parties. The attack can be conducted within the same network or on the Internet. There are a variety of ways to conduct a MITM attack using protocols such as ARP, DNS, ICMP, DHCP, SSL/TLS, and BGP.

- Password: This is the most common and obvious way to attack computer systems or smartphones. The attackers use a variety of techniques, including brute force, dictionary, phishing, shoulder surfing, key loggers, video recording, replay, credential surfing, and password spraying [13].

- Trojan Horse: This is a malicious program in the guise of a standard harmless program. It can initiate actions without the user’s approval once it is installed. Trojan horse attacks involve hiding a hacking program and dispatching it at the right time. There are many such Trojan horse techniques [14], including ArcBombs, Backdoors, Banking Trojans, Clickers, DDoS, Downloaders, Droppers, FakeAV, Game Thieves, Instant Messaging, Loaders, Mail Finders, Notifiers, Proxies, Password-stealing ware, and SMS. Almost any software is vulnerable to Trojan horse attacks.

- Virus: A virus is malicious code that attaches to a host’s executable file. The code executes whenever the file is opened. When the infected file is sent across computer systems, the virus spreads [15]. They are usually spread through emails or shared mass storage devices.

- Worm: A worm is a type of malware that replicates itself and spreads across computers without any interaction from the user [16]. They consume memory and network resources, thus causing the system to hang. They can also allow access to attackers remotely.

- Spyware: This is software secretly installed on the victim’s computer or a computer belonging to an organization that monitors and gathers information on a user’s online activity, websites visited, and other personal information. Spyware, also known as privacy-invasive software, is a prevalent issue in today’s computing landscape, often installed without a user’s full knowledge or consent [17].

- Adware: This is a kind of spyware that runs unwanted advertisements and may contain malware that can get installed on the user’s computer when the user clicks on the links [18]. It could also be installed due to unintentional drive-by downloads.

- Rootkit: This is a software tool used to take over control of the intended computer and run commands on it with administrator privileges as it operates inside or near the kernel. It can hide keyloggers that capture the keystrokes and steal information such as passwords, credit card numbers, and online banking details [19].

- Botnet: A botnet is a group of interconnected malicious computers that coordinate to attack other machines [20]. A single attacker (botmaster) can create an interconnected robot network (a botnet) with malicious code and control it for attacking. The attacker can initiate various types of cyberattacks, such as DDoS, phishing, click fraud, and spam.

- Data Breach: A data breach is when unauthorized personnel gain access to sensitive data or confidential information. Some examples of sensitive data include social security information, bank accounts, healthcare data, and corporate information. Sensitive information can be stored in paper files, hard disks, thumb drives, and intellectual property. In these attacks, the confidentiality of breached data is lost [21].

- Advanced Persistent Threat (APT): An APT remains undetected for an extended period after an attacker gains unauthorized access to a computer network [22]. This is a sequential and long-term attack that persists in the system. These attackers have a planned goal consisting of theft of data, gaining access to system resources, using social engineering techniques to lure users, staying in the system as long as possible, and moving around the system with the best attacking strategy without being noticed by any existing preventive tools.

- SQL Injection: This attack consists of accepting SQL queries as inputs into a vulnerable database system that leads to exploitation of the database. The malicious SQL query allows the attacker to gain unauthorized access to the database. An SQL injection attack consists of the insertion or “injection” of a SQL query via the input data from the client to the application [23]. A successful SQL injection exploit can read sensitive data from the database, modify database data (Insert/Update/Delete), execute administrative operations on the database (such as shutting down the DBMS), recover the content of a given file present on the DBMS file system, and in some cases issue commands to the OS.

- Supply Chain: A supply chain attack [24] is one in which many vendors in the chain are rendered vulnerable when a single vendor is compromised. The attackers can obtain maximum benefit by concentrating their attack on a single vendor and then gain access to global data through the chain of connected vendors. A supply chain system consists of many vendors for a given customer. If one of the vendors is breached or attacked in the chain, it may influence other vendors. One of the vendors may have been breached due to security vulnerabilities in their site. When there are many suppliers, one or more of them may be prone to security vulnerabilities. Multiple targets can be compromised from a single vendor.

- URL Interpretation: URL interpretation [25] exploits the vulnerability of URLs by changing and manipulating the URL meaning without changing or altering the syntax, which allows the attackers to access unauthorized data from the server associated with the URL. Attackers can alter and fabricate URL addresses to access victims’ private data and information. It is also known as URL poisoning. An attacker may use this fake URL to gain administrative privileges and launch other attacks.

- Insider Threat: Insider threats [26] happen when employees within an organization have privileged access to critical information and misuse their credentials for personal gain. This could render the organization system vulnerable to security attacks. These employees may have current credentials to access private data at an employer site. They may be seeking financial gains to extort the employer using the accessed private data.

- Eavesdropping: Eavesdropping [27] is stealing transmitted information over an unsecured network. It consists of capturing network traffic. The attacks can be static or modification attacks. In static attacks, the data may be used later to capture valuable information. In modification attacks, the data are only useful if an attacker can modify it while the communication is in progress. A MitM attack can be used with the captured data.

- Cookies: Cookies contain information about a machine, sites browsed, clicks made, location, and possibly login information [28]. Attackers can steal or hijack a cookie and capture this data. When a user visits a website, cookies may be enabled to play advertisements and capture the user’s browser activity. Although cookies help speed up access to visited websites, they help attackers piggyback malicious programs along with legitimate ads.

- Social Engineering: These attacks [29] are used to convince a victim to share private data or perform some actions that will enable an attacker to inject some illegitimate code into the system. This is one of the ways attackers can install malware on the victim’s site.

There are many standards that classify security vulnerabilities and cyberattacks. With respect to these standards, such as CVE [30], CWE [31], and MITRE ATT & CK [32], their root causes and mapping to attacks are based on current systems, products, and software engineering methodologies. Bare machine computing is a different concept and approach. In this paper, we only consider generic attributes that can be compared with the BMC paradigm and its applications. To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the BMC paradigm, we chose to compare conventional systems and BMC systems. First, we identify and discuss conventional system guidelines and conventional system characteristics. Next, we give an overview of the BMC paradigm, the compilation process in BMC development, and the integration of direct hardware interfaces in BMC code. We include code snippets that give insight into how BMC applications directly control the hardware. Then, we identify and discuss BMC system guidelines and characteristics and compare them with conventional system guidelines and characteristics to determine the resilience or exposure of each system to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Using the above 22 common cyberattacks, we examine their primary root causes and preventive mechanisms given in the existing literature. We evaluate the BMC paradigm with respect to these cyberattacks by analyzing how the attacks are related to their root causes and preventive mechanisms. We then look at the applicability of root causes and preventive mechanisms to BMC systems. This enables us to evaluate the security strengths of the BMC paradigm and its ability to resist these cyberattacks. We also discuss the significant contributions of this research. Our evaluation using the relevant existing literature demonstrates that BMC systems are more resilient than conventional systems to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Overall, this comparison highlights the advantages of using the BMC paradigm to build more secure computing systems.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of conventional computing systems, including their applications, guidelines, and characteristics. Section 3 provides details on BMC systems, including their background, guidelines, and characteristics. It also establishes a knowledge base for evaluating the security potential of BMC systems. Section 4 compares BMC systems and conventional computing systems with respect to cybersecurity vulnerabilities using the respective guidelines and characteristics. Section 5 identifies cyberattacks’ root causes and preventive mechanisms and evaluates the resilience of BMC systems to these cyberattacks. Section 6 discusses the significant contributions of this study. Section 7 concludes the article and suggests more research in secure computing systems.

2. Conventional Systems

Conventional systems evolved from mainframes, resulting in desktops, laptops, smartphones, and IoT devices. Most of these systems use some form of an OS or kernel. During the mainframe era, there was no Internet and no online users. The OS was used as a mediator for many users and application programs to provide their services. The OS protected itself from users and protected users from each other. As computers evolved over the years, OSs continued to play a significant role in building computer and information systems. Later, when the Internet became the primary vehicle for communication between users, communication merged with computing, thus extending the OS’s role to provide communication. Now, most computing systems have computing and communication on a single device. For example, smartphones perform computing, communication, and control as part of the same system, and they are seamlessly homogenized to work on the Internet. Smartphones resulted in user-centric computing serving client applications.

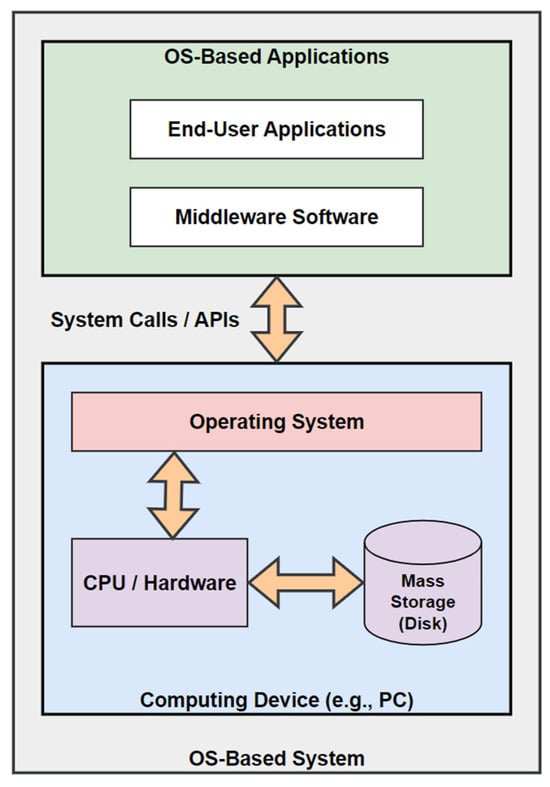

Figure 2 illustrates how computer applications use system calls or APIs provided by the OS. Application programmers are isolated from hardware and focus on writing applications in each programming language. There is heterogeneity at every level, including communication protocols, system libraries, device drivers, third-party software, network interface cards, standards, OSs, and computer architectures. They follow an evolutionary path and continue changing and enhancing products rapidly.

Figure 2.

OS-based system.

During this evolution, open systems, standards, free software, free access, remote control of devices, and globalization proliferated worldwide, resulting in billions of users [1] and the IoT [33]. A given application’s security depends on the security of the underlying OS and may be compromised due to OS vulnerabilities [2]. As OS versions and releases often change, its platform-related entities change accordingly. These fast changes in hardware and software may also introduce more security vulnerabilities.

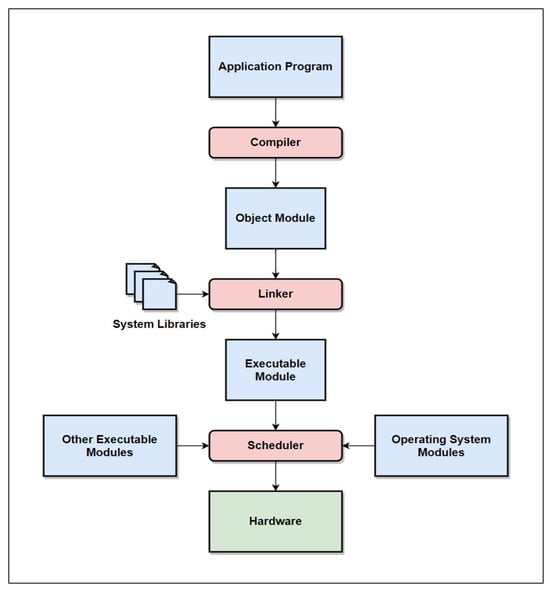

Figure 3 illustrates a typical application development process and its development and execution environments. A given application only controls the functional flow and plays no role in maintaining an execution environment. When an application is created, it is linked with the system or external libraries. When an application is running, its execution is dependent on a variety of OS components. In addition, there may be other applications running in a multi-programming model. Today’s Internet applications running on a device may be affected by cookies, network programs, sockets, shared memory, and background downloads. As the current OS provides computing, communication, and control in each box, a running application may be exposed to the side effects of the host OS and other applications running at the same time.

Figure 3.

Conventional application development process.

Conventional system properties are typically classified into two categories: system guidelines and system characteristics.

2.1. Conventional System Guidelines

In our literature review spanning many references, some of which are included in this article, we have identified 20 conventional system guidelines as described below. This list is not exhaustive; however, it serves as a basis for comparison with BMC system guidelines.

- System Approach: Over a 50-year period, computer architectures have been following an evolutionary path in processors and OSs, which are the backbone of all computing and information systems.

- Open Systems: During the 1960–1990 period, most computer and information systems were closed systems and proprietary in nature, thus protecting a given industry’s intellectual property. These systems and their know-how were limited to confidential and authorized users based on their need-to-know policy. Due to the emergence of the Internet and globalization, most of the systems and their knowledge became open to the world. While an open system allows for easier resolution of security vulnerabilities, it also means that attackers and developers have access to the same information, which implies that it is not more secure.

- Global Focus: Many information systems are architected, designed, and implemented for a global market, as this market is much larger than a given country’s local market. This resulted in large-scale commercialization on the Internet and more revenues and profits for related industries.

- Global Users: Computer and information system users are all over the world, and they are not always easily identifiable and trackable.

- Equal Access: With an Internet connection, any global user has access to most information on the Internet; this includes attackers as well.

- Learning and Knowledge: Information about system internals and system security is often posted on the web. This helps the attackers to easily access the information they need at a faster pace. Defenders also put problems and fixes on the Internet as soon as they are discovered. This enables attackers to create new attacks with less effort. The following two quotations from [34] clearly illustrate the side effects of free learning and knowledge on the Internet. (a) “Open-source Intelligence (OSINT) tools could gather data from various publicly available platforms and thus help hackers identify vulnerabilities and develop malware and attack strategies against targeted CI sectors.” (b) “OSINT tools: indirect reconnaissance data, proof-of-concept codes, and educational materials. The thematic results from this study reveal an increasing amount of open-source information useful for malicious attackers against industrial devices, as well as the need for programs, training, and policies required to protect and secure industrial systems and CI”.

- Unrestricted Internet access: Many Internet and web applications are available for all users worldwide with an Internet connection. Advertisements swamp systems almost instantly after access to the Internet. Searching online for a particular product or service immediately results in advertisements for related products or services. The advertisements may continue persistently for an extended period. This may be beneficial for some users to quickly learn about products and services. Still, it has many side effects, including a waste of time for users, distraction from a user’s current tasks, and loss of privacy of email addresses, phone numbers, and other personal information. Personal information shared with online vendors to conduct any transaction on the Internet may be distributed to other vendors.

- Layered Systems: All computer and information systems are layered with respect to architectures, protocols, interfaces, and security. Attackers may exploit these layers to suit their attack environment.

- Heterogeneity: Current computer and information systems encourage heterogeneity at every stage of building computer and information systems, assuming that it will promote innovation and productivity [35]. Instead, heterogeneity and incompatibility at every level interfere with the main goal of building end-user applications. With today’s high-performance processors coupled with cheap hardware, due to heterogeneity, tweaking small improvements may not pay off as much as before. There is a need to reduce heterogeneity by developing basic building blocks for computing at every level that are long-lived. Heterogeneity exists in processors, OSs, protocols, user interfaces, programming languages, hardware, software, including third-party software, and more. This increases the complexity of computers and information systems [36] and provides more avenues for attackers to exploit cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

- User/Developer Convenience: User convenience takes higher priority over other design issues in defining system guidelines. For example, it is convenient for users to choose a short-length PIN code for bank transactions, which may not be secure. Online teaching is convenient for faculty and students, but it may not be secure. As it is convenient for businesses to use the Internet for all transactions, physical security and privacy may be ignored. Many online transactions require personal information, causing a loss of privacy. In fact, without a smartphone, it is impossible to do many Internet transactions today. These actions may indirectly result in system vulnerabilities and cybersecurity weaknesses. In addition, developer conveniences, such as using a different programming language for a special purpose, using DLLs, downloading files and software, remote logins, remote administration, and third-party software, may also affect cybersecurity [37].

- Training: All users and customers must obtain training as needed.

- Software Installation: This is conducted online due to convenience and frequent changes.

- Wi-Fi: Wireless connections are commonly used for computing devices such as a mouse, keyboard, headphones, and Internet access. Most Internet transactions are conducted using Wi-Fi and often with a smartphone.

- Scripts and Batch Files: Scripts and batch files are used by administrators locally and remotely for convenience. This enables them to work remotely.

- Attachments and Links: Email attachments are commonly used for convenience. Web links are also allowed in the emails for user convenience.

- Social Media Platforms: They have become a part of everyday lives due to globalization, enabling speedy communication and sharing of information online.

- Advertisements: There are advertisements appearing continually in social media, smartphones, TVs, computers, and websites.

- Unsolicited Web Sites: Mostly for commercial and marketing reasons, unsolicited links to websites frequently appear in email and other Internet applications. It is not easy to distinguish between a link to a good site or a bad one.

- Automated Tools: Automated tools such as Wireshark and reverse engineering tools such as Object-dump are available on the Internet. There are many such tools available for attackers to use.

- Cookies: Cookies are used to track visits to websites for marketing purposes and user convenience, but they can also be used to launch malware.

2.2. Conventional System Characteristics

The following characteristics were obtained from our literature review of the security papers listed in this article. We have identified 20 conventional system characteristics as described below. This list is by no means exhaustive; however, it serves as a basis for comparison with BMC system characteristics.

- OS/Kernel/Embedded: Most systems have an OS or kernel. They can also be embedded systems. Due to the complexity and size of modern OSs, lean operating systems were designed to improve security and reduce complexity. Some middleware (e.g., the OS) makes software systems easy to build and isolates programmers from hardware intricacies.

- Applications: Computer and information system applications are platform-centric and computing device-dependent. No proper abstractions have been used to build applications. Thus, applications are redundant on different platforms. A web browser on a smartphone is different from that on a PC. Email systems are also different on various platforms. Due to this redundancy and lack of proper abstractions, an end-user application may be duplicated many times, resulting in a large application space.

- Programming Languages: Multiple programming languages are used in conventional systems. Different languages are often chosen based on the type of application, programmer’s skills, convenience, and performance. Performance may not make much difference as current processor speeds are increasing in a short period.

- Executables: Different operating systems support different executable formats. Some applications may have many executables, thus creating multiple address spaces. Inter-module communication may require message passing between modules.

- Linking: Dynamic linking is used for many reasons. It reduces the executable sizes, as some modules can be linked at runtime. It is also convenient, as the compiler does not know where the system libraries and other modules are loaded in memory at compile-time. In addition, in multi-module design, the interfaces to other modules are not known at compile time.

- Loading: Dynamic loading and linking are related. Dynamic loading at run time is also very convenient, as noted above for linking. In modern OSs, dynamic loading and linking (DLL) is commonly used to make the executables smaller and to enable use of external modules as needed at run time.

- Multi-tasking: Multi-tasking or multi-programming is necessary for all computing systems, as the CPU cannot be kept busy all the time. Most programs need I/O; they cannot run when an I/O request is pending. In conventional systems, when one program is idle, other programs and the OS can run. A given program may not be running alone until its completion.

- System Calls/API: OSs provide system calls to communicate with the hardware. OSs also provide APIs, enabling programmers to access hardware interfaces. System calls use interrupts to invoke OS services.

- Sockets: Operating systems provide socket interfaces to communicate between processes within a node or with a remote node.

- Open Ports: When a packet arrives at an OS, it uses the destination port number in the packet to deliver the packet to its application. A given application running in the machine uses a designated port number to communicate with other nodes. There may be some ports open in an OS to accommodate unexpected applications running in the machine.

- During Execution: In an OS environment, a given application, other applications, and OS processes and threads run concurrently. Some of them may interact with others intentionally or unintentionally.

- Event/Interrupt Driven: Most conventional systems use event-based and interrupt-based processing.

- Shared Memory/Message Passing: Both are used for local communication, and message passing is used for remote communication.

- Concurrency Control: Inter-process communication in an OS environment may require concurrency control mechanisms. Locking and semaphores are used to handle concurrency.

- I/O: Most I/O is interrupt-driven in an OS.

- Third-Party Software: Usually, there is software from many vendors in current systems.

- Network Interfaces: Protocols such as TCP or QUIC have many interactions between a server and a client during connection establishment, data transfer, and connection termination. Security protocols such as TLS also require many interactions to ensure secure data transfer.

- Internet Communication: In conventional systems, most communications are conducted through the global Internet. There are billions of users on the Internet while a given communication is in progress.

- Internet Downloads: For convenience and data sharing, users download software, applications, files, pictures, private data, etc. on the Internet. During downloads, a user may have to enter personal data, resulting in a loss of privacy.

- IoT: The IoT is growing at an exponential rate. Currently, there are 17 billion IoT devices [38].

3. Bare Machine Computing (BMC) Systems

This section describes the BMC paradigm [39] and gives some insight into BMC system development. The following subsections provide some details on building applications using this paradigm. A variety of real-world BMC applications have been built, demonstrating the feasibility of this paradigm. BMC is an alternative approach for building computer applications without running a centralized kernel or an OS. The BMC paradigm provides other benefits, including significantly reducing obsolescence and cybersecurity risks.

3.1. BMC Paradigm

The BMC paradigm was originally motivated by the rapid obsolescence [4] and continuously emerging security vulnerabilities in computer and information systems. Obsolescence impacts computers and information systems, causing hardware and software to be replaced before their useful life span. The topic of obsolescence is not within the scope of this paper. The BMC approach resembles computing when it started in the 1960s using bare hardware operated with switches and buttons. In current technology, hardware is cheap, provides many functionalities, and allows more logic to be placed on a single chip. It also allows computing devices to be bare, as a processor can provide needed hardware interfaces to application programmers.

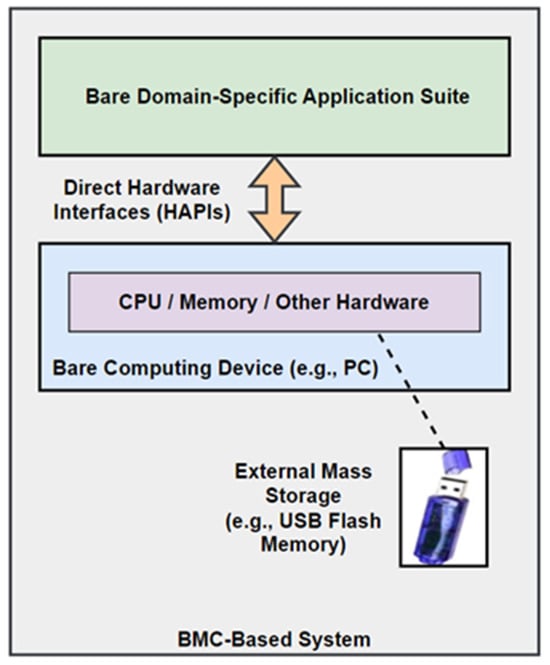

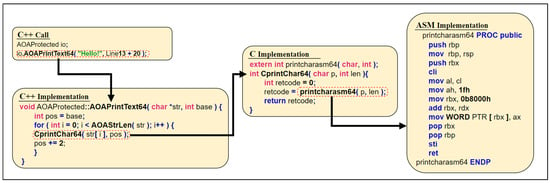

In a BMC system, as shown in Figure 4, applications directly communicate with the hardware without any middleware. For example, suppose we want to print the text “Hello” on the screen. Figure 5 illustrates how a programmer can directly control writing on the screen without using an OS. This simple example shows how a programmer can directly access the hardware through C++ -> C -> assembly as a single thread of execution without interruption. It also shows how a programmer views the underlying hardware in the BMC paradigm. It is possible to automate this process to make it user-friendly for developers. In this example, the assembly call writes string data to the video memory location at 0x000b8000. A BMC programmer controls all the code shown here. There are no other dependencies in the BMC code. This philosophy is carried throughout the development process of any BMC application. Using this approach, we can write all direct hardware interfaces needed for information systems applications and development. Eventually, these direct hardware interfaces can be built on the processor chip. If the output must go to graphics memory, the same logic is used with the help of a bare graphics driver. A BMC system is not the same as a bare metal system or embedded Linux [40], as BMC is a general-purpose computing paradigm. BMC servers are not the same as bare-metal servers or virtual servers in the cloud [41], which require some OS to provide services.

Figure 4.

BMC-based system.

Figure 5.

Hello program using the BMC paradigm. * Refers to a pointer declaration in C++.

The BMC paradigm is based on an application-oriented approach. It divides all computer applications into domain-specific applications using object-oriented abstractions. Examples include banking, online transactions, manufacturing, payroll, desktop and office applications, accounting, email, chat, and browsers. A given domain-specific application may contain one or more applications bundled as a single domain application suite used at a given time. One such example is text processing, spreadsheets, and Internet search. Each domain-specific application suite contains all the necessary code to run on a given bare machine. Although BMC currently chooses Intel processors and their instruction set architecture, it can be adapted to work with any other computer architecture as needed. The BMC paradigm assumes hardware integrity. The paradigm is applicable to any computing device, including a smartphone.

In BMC, the first step is to make the computing device bare. This means it has no operating system, no hard disk (such as mass storage), and uses the BIOS for now. Eventually, the BIOS can be bundled with the associated application suite. The code can run on older or newer Intel processors, which are ×86 and ×64 compatible. The second step is to write the software in C/C++ and a small amount of assembly code where needed. The BMC paradigm is based on a single programming language environment. Boot, loader, and interrupts are written in assembly. One or more applications can be compiled as an application suite, generating a single monolithic executable. This is statically compiled and linked with no external software or libraries. The small executable contains all the required code to run its application suite. A given application suite executable is typically less than 2 MB. It carries the necessary bare drivers [42] and code to support the required functions. There are no kernel or system calls and no OS-related management functions.

The application programmer controls the hardware and required interfaces, and the application suite directly communicates with the hardware without using any middleware. The BMC paradigm also uses bare devices to communicate on the Internet, forming a bare Internet [43]. Only authorized bare users can communicate on bare Internet.

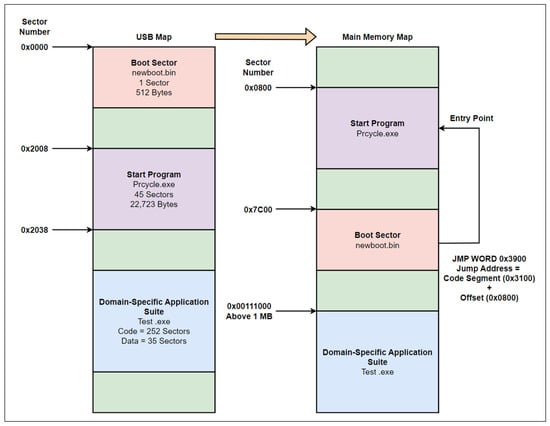

Each application suite can define its own memory map, as shown in Figure 6. This memory map shows how content in an application suite USB is copied into main memory. The boot code from sector 0 is copied into memory location address 0×7c00 (for IBM Compatible PCs). The start program from the USB is copied at memory location 0×600 and includes two header sectors. The start program is loaded in the real memory area. After the boot program runs, it jumps to 0×3900 in real memory to run the start program. When the start program runs, it copies the domain-specific application suite executable from the USB into the memory location starting at 0×00111000, which is above 1 MB and is in protected memory. When the start program is completed, it starts executing at 0×00111000 (which is a main () entry point). All these numbers are extracted by using Microsoft tools to identify entry points and other components in the executable. Notice that there is no need for virtual memory in BMC systems, as there is no OS and only a few applications are bundled and run at a time. Each domain-specific application suite has its own characteristics and can be loaded in custom locations in memory accordingly. This process can also be automated in BMC systems. The above memory map can be customized for domain-specific application suites, which shows simplicity and flexibility in building BMC applications.

Figure 6.

Memory map.

As per our knowledge, there is no true bare machine research/development/product like BMC. However, there is ample related work in making the OS lean, moving OS functions to application space, bypassing the OS to gain fast access to hardware resources, and designing an OS for IoT devices. Examples include the exokernel OS architecture enabling applications to manage the hardware and improve performance [44]; Tiny-OS for low-power wireless devices [45]; and Palacios and Kitten, a lightweight OS and VMM (virtual machine monitor) for high-performance computing [46]. Microkernel and related approaches [47,48] keep only essential OS services in the kernel to increase performance in applications such as cloud computing. IO-Lite and kernel bypass techniques [49] provide direct I/O access to applications to speed up I/O. For data center servers, a customized OS [50] can be used to bypass kernel services. RIOT is a small OS suited for IoT devices [51]. Tradeoffs in designing minimalist instead of functionality-rich platforms are analyzed in [52]. The BMC approach is a minimalist approach, where there is no OS or kernel.

3.2. Compilation Process

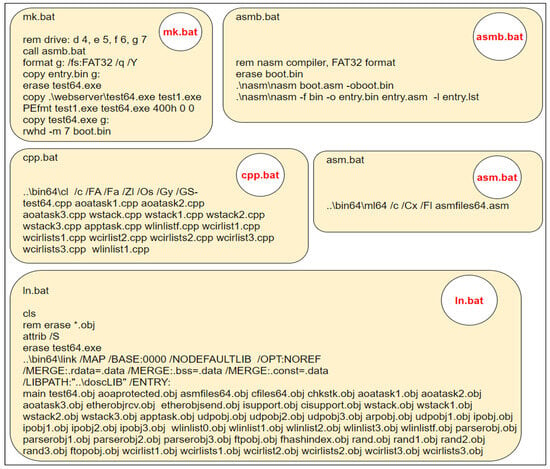

This section illustrates compilation and the BMC development process. It shows that developing BMC applications is simple and independent of other development environments, which change often. It also shows that the BMC application suite is a single monolithic executable with one address space for a given set of applications. All the batch files used are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Compilation process. * Refers to all file names with the .obj extension in the command rem erase *.obj.

Currently, the development process in the BMC uses batch files and takes complete control by using a particular version of Visual Studio (VS 64-bit) as it changes often. These batch files allow us to conduct a compilation process independent of any version of the OS release. At present, we use a Visual Studio/bin directory to compile and link our bare code. The development environment does not use/lib and/include files. A boot.asm has a boot code, and entry.asm has an entry code for the 64-bit application suite. The asmb.bat file is used to generate these binary files, which are written in the NASM assembler. The mk.bat file is used to create a bootable USB, which has boot, entry, and test64.exe (application suite). The PEfmt tool is written for BMC to properly organize code and data segments as needed for the Microsoft PE format.

The asm.bat file is used to compile MASM assembly code that provides direct hardware interfaces. There is a cpp.bat file in every directory that has C/C++ code. The cpp.bat file shown below is for the main directory in the application suite. Similarly, there is a separate cpp.bat file in each directory, where there is C/C++ code. The object files from each directory are used together to run a link process. The ln.bat file creates an application suite executable named test64.exe. This description of batch files refers to creating a multicore web server using the BMC paradigm. This total control of compiling, linking, and creating a static executable prevents other malware from being linked with this application suite at run time.

3.3. Sample Direct Hardware Interfaces

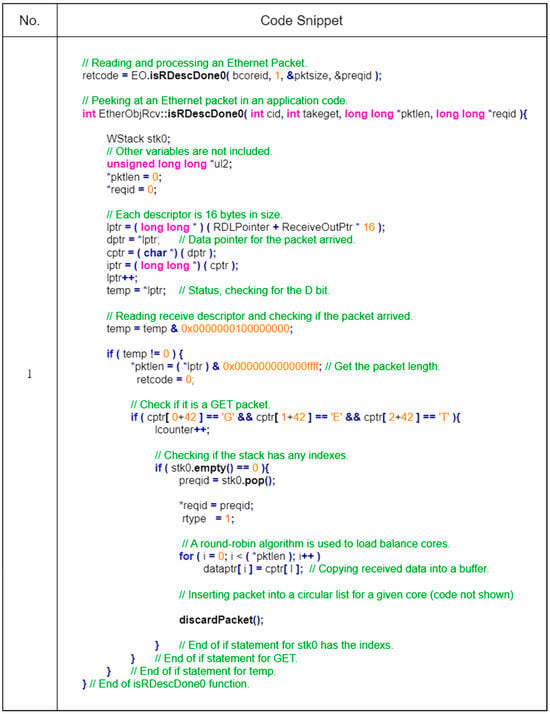

Some sample direct hardware interfaces, such as tasking, reading data from an Ethernet buffer, and processing a received packet, are discussed in the following sections. The code snippets demonstrate how the BMC code integrates all components seamlessly without any layers. It also shows that a programmer controls all hardware elements and software structures, such as Ethernet buffers.

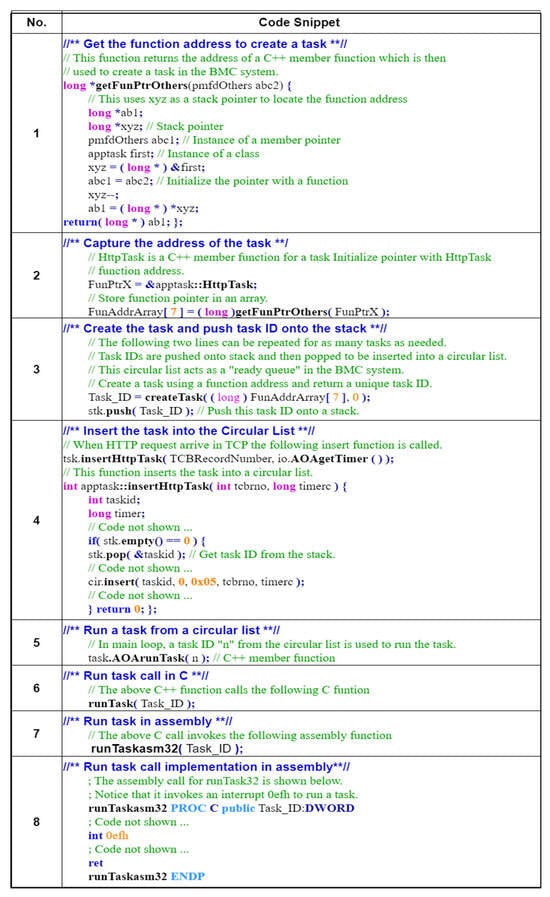

3.3.1. Creating, Inserting, and Running a Task

The code snippets in Figure 8 from a 32-bit application suite for a web server show how a task is created in the BMC paradigm. Notice that task generation is bundled with the application suite and is not visible to outsiders, which prevents intrusion into the code. This code is generated, statically compiled, and linked. A given application suite decides the task creation and its control flow. The deleting task is not shown here. The code is self-explanatory and follows chronological order.

Figure 8.

Task creation.

3.3.2. Reading and Processing an Ethernet Packet

In the BMC paradigm, device drivers are part of an application suite. They are written to work without using any OS system calls or API. All device drivers must be written from scratch and are known as bare device drivers. There are two data structures in the Ethernet driver, known as the transmit and receive descriptor lists. These are circular lists with 4096 entries. When a packet arrives, the hardware sets a bit known as descriptor done (DD). Application programmers can read this bit to check if a packet is received. Similarly, when a packet is transmitted, the hardware sets the transmitter DD bit. An application program can examine these DD bits to communicate with the Ethernet control hardware.

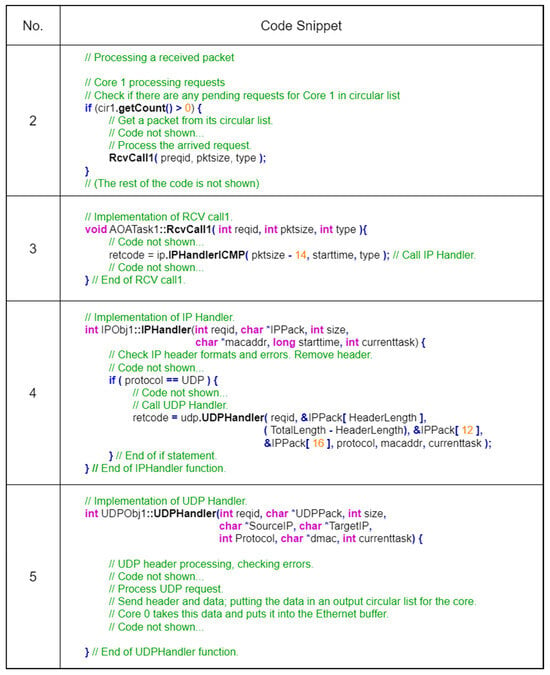

For receiving a packet, if a given slot’s DD bit is set, then this packet will be read and passed onto the application, as shown in Figure 9. The function isRDescDone0() in Code Snippet 1 shows how an application can peek into the Ethernet receive buffer for an HTTP GET request and copy the GET data into another buffer. After copying the data, it calls discardPacket() to reset the DD bit. Code Snippet 2 shows how a received packet invokes the RcvCall1() function to process a request, and Code Snippet 3 shows how it calls the IPHandler() function. Code Snippet 4 illustrates how it calls the UDPHandler() function, and Code Snippet 5 shows the processing of the UDP packet with comments, as this step has a large amount of code, which is not shown here. In essence, this code demonstrates that all the Ethernet packet processing is done as a single thread of execution without any layers. In addition, this is application code designed and controlled by an application programmer without the intervention of any middleware. It is event-driven with polling to receive packets. Send is not shown as it is like receive.

Figure 9.

UDP-based protocol.

3.4. Summary of the Above Code Snippets

In the above Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, we discussed the use of direct hardware interfaces, the BMC development methodology, and some application code snippets. It is evident from these discussions that this approach is different from conventional methods. When a machine is made bare, the programmer controls software development at compile time and run time. The programmer also controls run-time behavior and does not allow any unintended functions to interfere with a given application suite. Hardware interfaces are included at development time, and flow control cannot be altered at runtime by other applications. This is truly an application-oriented model with a security-by-design approach. The task creation code shows how it is intertwined with an application suite, thus allowing the system to perform only intended tasks. The Ethernet peeking demonstrates that all device drivers are also seamlessly integrated with a given application suite. The packet processing shows how Ethernet, IP, and UDP are integrated as a single thread of execution instead of going through different layers. In this approach, packet processing goes through a simple invocation of calls from one protocol to another. Overall, a given application suite is custom-designed and simple; there is only one user mode; the machine is bare and has no valuable resources; and the programmer has control at all stages.

3.5. Properties of the BMC Paradigm

There have been many real-world applications built to demonstrate the feasibility of bare systems using the BMC paradigm, including chat [43], Web servers [53], USB drivers [42], and Web mail servers with TLS [54]. These real systems are used to identify system guidelines and system characteristics.

3.5.1. BMC System Guidelines

- System Approach: It is a revolutionary approach that was invented to address obsolescence and security problems. It makes applications independent from the execution environment, and all computing devices are bare.

- Open/Closed System: It is a closed system. Injecting an attacker’s code is not possible. Open source must not be confused with open systems. The BMC is a closed system. The computing box is bare, and the application running in the bare box is not accessible to hackers. In case hackers create a similar system, they can only hack their own system, not others. If we make an open system, security vulnerabilities are easy to fix, but hackers and developers are at the same knowledge level.

- Global Focus: It has a local focus. It is architected, designed, and implemented to avoid global users.

- User USBs: There are dual USBs (the first for booting and the second for an application suite). Both USBs must be physically secured.

- Equal Access: All bare users have equal access.

- Education and Knowledge: Restricted to authorized bare users.

- Layers: There are no layers at any level.

- Bare Internet: To make BMC viable, a bare Internet concept [43] is introduced. In a bare Internet, all intermediate nodes, such as routers and gateways, must be bare, and they must be physically secured. At present, a bare Internet is overlaid on the existing Internet.

- Heterogeneity: No heterogeneity is allowed in programming languages, hardware, and software. The security of systems and applications is more controllable.

- User/Developer Convenience: User convenience takes lower priority over other design issues in defining system guidelines. For example, a system administrator must physically distribute user accounts to guarantee the authentication of users. This is not convenient, but all other electronic means may not be secure. The BMC systems are not global, and the users are limited within a given domain-specific application. These systems are designed for secure domains, not for a global world. Non-bare users can use conventional systems if BMC systems do not fit their needs. BMC systems provide an alternative approach to current computing systems.

- Training: All authorized bare users must have consistent training and education.

- Software Installation: Online installation is not allowed. There is nothing to install in a bare machine. The user carries secure USBs. These USBs are distributed to authorized bare users by physical means.

- Wi-Fi: Wi-Fi is currently not supported due to its security issues.

- Script and Batch Files: These are not allowed.

- Attachments and Links: Attachments and links are not allowed in emails.

- Social Media Platforms: There is no support for social media applications. Social media can use the conventional Internet, which is isolated from a bare Internet. This approach will reduce the number of users on a bare Internet.

- Advertisements: Advertisements are not allowed. All domain-specific applications and their users are properly authorized and tracked on a bare Internet.

- Unsolicited Websites: Only access to authenticated bare websites is allowed.

- Automated Tools: Automated tools are designed to work with only bare computing devices and applications. Their use is restricted to bare users only.

- Cookies: No cookies are allowed.

3.5.2. BMC Characteristics

- OS/Kernel/Embedded: The OS/kernel/embedded concept is eliminated. There is no such centralized program; each domain-specific application is a self-controlled, self-managed, and self-executed entity. There is no interaction with entities outside an application suite. As there is no OS/kernel, a user carries a flash drive with boot code and a domain-specific application suite. Figure 6 shows a memory map for a flash drive containing a client’s UDP-based chat program.

- Applications: All computer applications are polarized as domain-specific entities. They are independent of any platform. In conventional systems, they are dependent on platforms and execution environments.We have developed and demonstrated numerous domain-specific applications, including web sites, webmail, email, VoIP, text-only browsers, editors, file systems, database applications, and chat. In these systems, there are bare servers and clients that run on bare machines. For example, in the chat domain, there are physically vetted users who communicate in their own domain. All these users are vetted and use bare machines. We use context-based authentication to validate users. This is one example of a domain. All the above domain applications were tested on the Internet with bare servers and clients. On the Internet, domain-specific applications are used to communicate securely within a domain using bare devices.

- Programming Languages: A single programming language (C/C++) is used to write applications, thus avoiding all heterogeneity in writing applications.

- Executable: It is a single monolithic executable, which implies a single address space. Only one executable format is allowed.

- Linking: Uses static linking, which prevents expanding the code segment to load foreign code. This provides ultimate security for the BMC applications, as malware code cannot be linked.

- Loading: Uses static loading, which prevents extending the code segment to load malware code.

- Multi-tasking: Multi-tasking is offered within an application suite controlled by an application programmer through events and its control flow.

- System Calls/API: There are no system calls or APIs available to the outside world (outside an application suite). It uses a direct hardware API, integrated within an application suite.

- Sockets: No sockets exist in the BMC paradigm, as there is no OS. Remote computer communication is implemented within a process and hidden inside an application suite.

For example, attackers use sockets to create man-in-the-middle attacks. In the BMC paradigm, sockets are not used as we build domain-specific applications with no open ports, not allowing users to create their own threads or processes. That is, items such as sockets are not needed in implementing BMC applications. The BMC paradigm inherently does not need such security-prone facilities as it does not have an OS. This approach is different from the “security through obscurity” concept. There are many such facilities that are not needed in the BMC paradigm, which offers inherent security in BMC applications. The following quote also supports your concern.

- 10.

- Open Ports: There are no open ports in BMC programs. As it is a domain-specific application suite, IP addresses and port numbers are managed within each application code in a hardcoded manner. This is not visible outside the application suite. When a packet arrives, its corresponding event (pre-defined) will call an appropriate method to process it.

- 11.

- During Execution: During execution, only one application suite runs. There is no interaction with other application suites or external modules in a bare computing device. No exploits are possible for an attacker.

- 12.

- Event/Interrupt Driven: The application suite is event-driven. Limited user interrupts are used for input.

- 13.

- Shared Memory/Message Passing: Only a shared memory approach is used within an application suite.

- 14.

- Concurrency Control: Concurrency control is avoided by using circular lists. The code is simpler and more directly accessible to the program.

- 15.

- I/O: There are direct hardware APIs that are hidden within an application suite.

- 16.

- Third-Party Software: There is no third-party software used in applications.

- 17.

- Network Interfaces: All network interfaces are hidden from the outside world. Attackers cannot use this direct hardware API.

- 18.

- Internet Communication: Communication on the Internet is restricted to a bare Internet and its bare users only.

- 19.

- Internet Downloads: No downloads are allowed.

- 20.

- IoT: All IoT devices must be bare computing devices and follow the BMC paradigm and its characteristics as described in this paper.

- 21.

- Application Program Control: A given application has its own control flow as intended at design time.

- 22.

- Computing Device: A computing device (PC, laptop, smartphone, or other) is bare, meaning that it has no intelligence, no OS, and no mass storage. It cannot boot or run until external media runs the boot code and loads an application suite controlled by the owner. The bare device has no valuable resources. Thus, a bare computing device can be used by any user at any time. When one application suite is running, another one cannot run; therefore, there is no intrusion from other applications. There is nothing in the bare computing device to be attacked, as there are no valuable resources when it is not running. When a bare device is running, it must be physically secured by the owner. Physical security at the bare box is not convenient, but it is required to guarantee security of the device and the running application suite.

- 23.

- Users: Only bare users can communicate with each other. For a given domain-specific application, there are a limited number of bare users. They must be physically authorized, authenticated, and controllable. We have not defined any formal methods for authentication at this point; however, we can use existing models in banking, driver’s license, etc.Our BMC system is totally controlled by its owner, with physical security. If a trusted user changes roles and tries to exploit other bare systems, this user can only damage his/her own system and not those of others. This is because an owner’s valuable resources can only be accessed by the owner’s application suite. When a BMC application suite is running, it is a closed system that performs only intended functions. In addition, when the roles of trusted users change, their privileges are changed in the system.

In the bare machine computing model, each bare box and an application suite is owned by an owner, and it is physically secured. If an outsider or insider gained the same knowledge as the original developer, then they could reconstruct a similar system of their own. However, they will be using their own system at their own location. All valuable resources are accessible only by the owner and stored in an owner’s detachable mass storage. Moreover, if they come through the network, they will not be able to access resources, as only trusted users are allowed to communicate within the domain. Users within the domain are vetted and authenticated to communicate within the group for each transaction. In this model, all users in the group must be physically trusted. This system cannot solve insider attacks and physical security violations. All the bare nodes in the system as well as on the network must be bare and physically secure. This is a harsh requirement, but it is necessary to build highly secure systems.

- 24.

- Messages: Each message is encrypted, integrity-protected, and authenticated using credentials physically given to authorized users by an administrator.

- 25.

- User-Secured USBs: Uses two USBs, one bootable and one with an encrypted application suite. These USBs must be physically secured by a user.

- 26.

- BIOS/Firmware: Bundled with a domain-specific application suite (not implemented currently).

- 27.

- Protocols: A bare machine connects to a network via wired Ethernet. Network protocols are limited to IP and UDP (TCP/TLS is used for demonstration only) implemented within the bare application. Other protocols are not available outside the application running on the machine. Each application communicates only with its peers to ensure reliability and proper functionality. Furthermore, protocols are integrated within the application, and there are no protocol layers as in a conventional system. The attacker does not have the path to invoke these protocols. Although an attacker can spoof IP addresses, such packets will fail user authentication and be dropped. Every packet has bare user authentication, encryption, an integrity check, and replay protection.

- 28.

- Passwords: No password files are stored on bare machines. Context-based authentication is used in bare systems.

The above BMC system guidelines and characteristics impose many restrictions for user options. This does not mean that the BMC applications have limited their user functionality. Any features or functions offered by conventional systems can also be provided by BMC applications. The functional requirements, design, and implementation are conducted in many ways to achieve the highest security possible by design. In many cases, a given functionality, protocols, and interfaces are hidden in an application. This is referred to as an A-to-A (application-to-application) approach.

For example, email attachments and downloads are not allowed in BMC characteristics. Users can still receive an attachment as a set of packets without explicitly providing attachment features. A sender and a receiver of an email application handle the disassembly and assembly of packets in their respective applications with a hidden knowledge of file characteristics. All emails and additional packets are encrypted when transmitted on a network. At the receiving site, it is ensured that this file data cannot be executed. Thus, attachments are handled differently than in conventional systems. Many other convenient features in conventional systems are implemented in BMC applications in a hidden manner.

Similarly, in BMC, software downloads are not allowed. All software that runs on a bare machine must be physically installed on a bootable USB by an authorized vendor for an authorized bare user. It is not convenient for bare users, but it is the most secure way to design BMC applications.

As per the following quotation, “In recent years, more advanced versions of “security through obscurity” have gained support as a methodology in cybersecurity through Moving Target Defense and cyber deception. NIST’s cyber resiliency framework, 800–160 Volume 2, recommends the usage of security through obscurity as a complementary part of a resilient and secure computing environment” [55].

BMC code can run on older and new Intel processors without any (or just a few) changes. The variety and breadth of the BMC work [43,53,54,56] show that it is possible to build similar systems for secure applications in computer and information systems. The BMC paradigm can thus be an alternative to existing OS-based platforms and applications with security by design.

3.5.3. BMC Limitations

As described before, the bare machine computing paradigm has unique system guidelines and characteristics to reduce obsolescence and provide inherent security in computer and information systems. However, this approach has its own limitations, as listed below:

- It is not a general-purpose global system.

- It requires physical security.

- It needs all users to be authenticated and vetted.

- It uses a domain-specific application approach (by dividing applications into domains).

- Only users within a domain can communicate.

- When domain-specific users change roles, their authentication privileges are revoked.

- All nodes in the network must be bare to guarantee high security.

- Uses the bare Internet, where all nodes are bare and physical security is assumed.

4. Comparison of Conventional and BMC Systems

This section compares system guidelines in Table 1 (20 items) and system characteristics in Table 2 (28 items). The system guidelines are informal requirements or policies needed to build a system. The system characteristics are inherent properties of a system. Some system guidelines and characteristics may be prone to security attacks. Some system guidelines and characteristics may be resilient to security attacks. Thus, we define two terms to compare conventional and BMC systems: PECSV indicates possible exposure to cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and PRCSV designates possible resilience to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. The references obtained from the literature review are shown in the tables to determine possible vulnerabilities and resiliency in BMC systems.

Table 1.

Comparison of System Guidelines.

Table 2.

Comparison of System Characteristics.

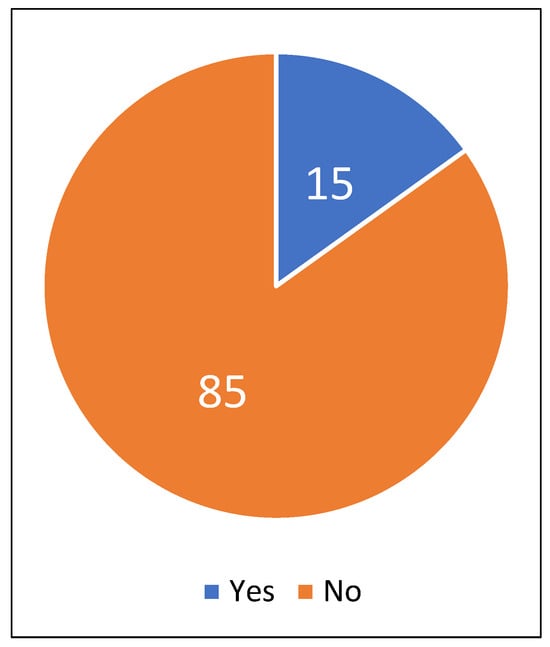

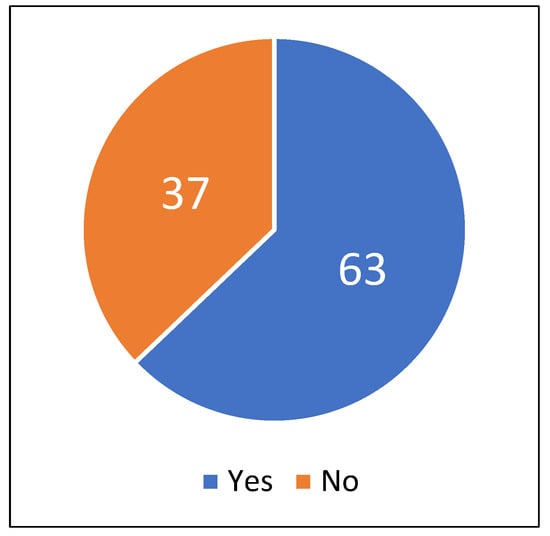

Using these two tables, we make the following observations. In Table 1, in conventional system guidelines, 15 out of 20 have possible exposure to cybersecurity vulnerabilities, whereas in BMC systems, 17 out of 20 have possible resilience to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Similarly, in Table 2, in conventional system characteristics, 17 out of 28 have possible exposure to cybersecurity vulnerabilities, whereas in BMC systems, 26 out of 28 have possible resilience to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Overall, BMC systems show possible resiliency, and conventional systems indicate possible exposure to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. This indicates that BMC systems are inherently secure by design.

5. Cyberattacks and Analysis

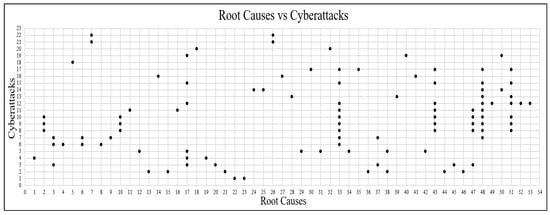

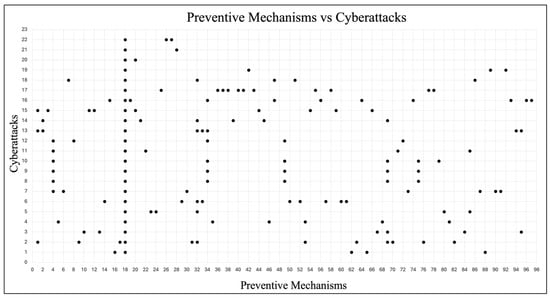

An attack can have many stages, such as reconnaissance, weaponization, delivery, exploitation, installation, command, and control (C2), and actions on objectives [94]. An attacker may select the stages in their attack methodology based on suitability for their execution plan. Each cyberattack can be traced to one or more root causes in an information system: hardware, software, firmware, OS, protocols, layers, complexity, programming language, humans, and more. Most of the literature on cybersecurity indicate that after an attack, it is typical to focus on the symptoms of an attack and fix the problem as needed. Many times, the roots of an attack may still exist and manifest as a new attack. This process goes on as a “cat and mouse” game in a never-ending cycle. It is essential to find and remove the root causes of cyberattacks to eliminate them. In current information systems, cyberattack roots are inherently hidden in the architecture, protocols, policies, procedures, objectives, requirements, design, and implementation of these systems. Thus, it is harder to remove them as it assumes global markets and users. The cyberattack space is infinitely large, as shown in Figure 1, and it is difficult to comprehend and address all possibilities for a given cyberattack. Eliminating the roots of cyberattacks may require revolutionary and non-evolutionary approaches, which are not the focus of current cybersecurity research.

5.1. Overview of Selected Cyberattacks

In this section, we analyzed the chosen 22 cyberattacks. The related work and the definitions of this cyberattack are provided in Section 2.1. We identified each attack’s preventive mechanisms and some root causes using the existing literature. These root causes will help to compare the security strengths and weaknesses of conventional and BMC approaches.

5.1.1. Buffer Overflow

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [8,95].

Root Causes:

- Lack of bounds checking in functions.

- Lack of input validation and sanitization by programmers.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Consistently update OSs, programming languages, and compilers to their latest versions.

- Implement code protection mechanisms.

- Use safe functions; validate and sanitize input data.

- Employ static code analysis tools.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.2. Phishing Attack

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [9,96].

Root Causes:

- Clicking links can trigger malware downloads or redirect to malicious websites.

- Downloading files can contain malicious code.

- Running downloaded code can execute malware and cause attacks.

- Messages from unauthenticated users may trigger attacks.

- Email addresses are easily obtained, aiding targeted attacks.

- Email attachments are a common phishing attack vector.

- Website phishing can mimic legitimate sites for credential theft.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Check website URLs.

- Scrutinize website design.

- Beware of urgency-based tactics.

- Enable two-factor authentication (2FA).

- Report suspicious activity.

- Utilize access control lists (ACLs).

- Employ email filtering.

- Use machine learning-based detection.

- Maintain regular backups.

- Prioritize strong passwords.

- Educate employees on cybersecurity awareness.

- Develop incident response plans.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.3. Ransomware

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [10,77,91,97,98].

Root Causes:

- Downloading email attachments.

- Downloading files from untrusted websites.

- Allowing downloaded code to run automatically.

- Attacker accessing OS APIs.

- Attacker exploiting hardware vulnerabilities (TPM: Trusted Platform Model, BIOS, firmware).

- Freely available educational resources on cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack techniques.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Deploy IDS (Intrusion Detection System) and IPS (Intrusion Prevention System).

- Utilize TPM. (Note: it was also found that TPM has security vulnerabilities).

- Maintain regular backups.

- Implement blacklist-based detection: block known malicious domains and IP addresses.

- Employ advanced ransomware detection: Use rule-based, statistical, machine learning-based, or hybrid techniques.

- Change the file extensions randomly.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.4. Denial of Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS)

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [11,99].

Root Causes:

- Allowing attackers to use a legitimate machine and infect it.

- Allowing attackers to flood requests.

- Freely available educational resources on cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack techniques.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Information entropy.

- Machine learning-based methods.

- Artificial neural networks (ANN).

- Statistical analysis.

- Flow statistics.

- Rate Limiting.

- TCP Proxies.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.5. Man-in-the-Middle (MITM)

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [12,78,100].

Root Causes:

- Attacker using public Wi-Fi access points.

- Using a secure socket layer provided by the OS.

- Exploiting protocol vulnerabilities in ARP, DHCP, DNS, ICMP, and IP.

- Using open-source automation tools.

- Using open-source OSs.

- Lack of proper authentication measures to validate users.

- Freely available educational resources on cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack techniques.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Enable two-factor authentication (2FA).

- ARP Spoofing Detection: cryptographic, voting-based, hardware, server-based, host-based solutions.

- DNS Spoofing Detection: entropy-based, cryptographic, artificial neural network (ANN) solutions.

- IP Spoofing Defense: router-based, host-based, hybrid solutions.

- SSL/TLS Solutions: detecting forged certificates, certificate pinning, multipath probing, forcing SSL/TLS connections, friendly MITM, TLS extensions.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.6. Password Attack

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [13,101].

Root Causes:

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

- Attacker modifying the number of password entry limits.

- Attacker accessing password files.

- Attacker accessing OS APIs.

- Attacker accessing system calls.

- Weak or predictable passwords.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Conduct penetration testing.

- Enable two-factor authentication (2FA).

- Enforce and manage strong password policies.

- Monitor activity for suspicious behavior.

- Employ a layered defense for a strong security posture.

- Limit attempts to enter a correct password.

- Change passwords frequently.

- Avoid using the same password for multiple accounts.

- Avoid passwords that are vulnerable to dictionary attacks.

- Use a password manager.

- Do not write down passwords.

- Consider password-less authentication techniques.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.7. Trojan Horse

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [14,102,103].

Root Causes:

- Users download either files or software.

- Running the downloaded code automatically.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

- Attacker accessing system calls.

- Attacker accessing OS APIs.

- An attacker using auto-run-in script files.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Avoid opening suspicious emails.

- Download software only from verified publishers.

- Scan URLs before clicking.

- Use antivirus software.

- Deploy honeypots.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.8. Virus

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [15,104,105].

Root Causes:

- User downloading email attachments.

- User downloading software.

- Users accessing fake websites.

- User using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Allowing script files in emails.

- Attacker using batch files.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Antivirus software.

- Firewalls.

- Keeping OSs up to date.

- Regularly backing up digital records.

- Scanning systems and USBs.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.9. Worms

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [16,106].

Root Causes:

- Downloading software.

- Downloading email attachments.

- Accessing fake websites.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Allowing script files in emails.

- Attackers using batch files.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Antivirus software.

- Firewalls.

- Keeping OSs up to date.

- Frequent backups of digital records.

- Scanning systems and USBs for malware.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.10. Spyware

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [17,107].

Root Causes:

- Downloading software.

- Downloading email attachments.

- Accessing fake websites.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Allowing script files in emails.

- Attackers using batch files.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Spyware detection algorithms.

- Antivirus software.

- Firewalls.

- Keeping OSs up to date.

- Regularly backing up digital records.

- Scanning systems and USBs for malware.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.11. Adware

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [18,108].

Root Causes:

- Marketing.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Uninstall adware.

- Reset web browser settings.

- Delete web browser caches and cookies.

- Use antivirus software.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.12. Rootkit

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [19,109].

Root Causes:

- Installing software online.

- Downloading software.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

- Accessing fake websites.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Using devices with infected firmware.

- Firmware vulnerabilities.

- Freely available educational resources on cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack techniques.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Antivirus software.

- Firewalls.

- Rootkit scanners.

- Avoiding phishing scams.

- Keeping OSs up to date.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.13. Botnet

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [20,110].

Root Causes:

- Software vulnerabilities.

- Downloading software.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Open ports.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Using an IDS (Intrusion Detection System) and an IPS (Intrusion Prevention System).

- Firewalls.

- Enforce and manage strong password policies.

- Access Control Lists (ACLs).

- AI and automation tools for security.

- Using bot managers.

- Enable two-factor authentication (2FA).

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.14. Data Breach

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [21,111].

Root Causes:

- User mistakes or negligence.

- Malicious insiders.

- Lack of physical security.

- Downloading software.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Regularly back up digital records.

- Cryptography.

- Identity and access management (IAM), such as strong password policies.

- Incident Response Plan (IRP).

- Enable two-factor authentication.

- AI and automation tools for security.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.15. Advanced Persistent Threats (APT)

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [22,112].

Root Causes:

- Downloading software.

- Clicking on email attachments.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Accessing fake websites.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

- Freely available educational resources on cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack techniques.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Access Control Lists (ACLs).

- Controlling external media use.

- Protecting valuable data.

- Managing endpoint security.

- Implementing Network Access Control (NAC).

- Blocking high-risk applications.

- Blocking known malware servers.

- Analyzing security breaches for prevention.

- Network and host hardening.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.16. SQL Injection

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [23,113].

Root Causes:

- System privileges are granted to the DBMS.

- DBMS bypassing OS controls.

- Failure to validate and authenticate user-entered data.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Input validation and sanitization.

- Using prepared statements.

- Firewalls.

- Controlling database permissions.

- Scanning code for SQL vulnerabilities.

- Using a secure ORM framework.

- Using properly constructed stored procedures.

- Applying the principle of least privilege to database accounts.

- Prohibiting default root or admin access to applications.

- Changing DBMS accounts from defaults to something else.

- Provide consistent training and reviews.

5.1.17. Supply Chain

The following root causes and preventive methods are derived from [24,114].

Root Causes:

- Providing backdoors in software and hardware.

- Exploiting OS vulnerabilities.

- Open-source code.

- Downloading software.

- Using an infected USB or other mass storage device.

- Users accessing fake websites.

Preventive Mechanisms:

- Implement honey tokens.

- Secure privileged access management (PAM).

- Implement a Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA).

- Identify potential insider threats.

- Identify and protect vulnerable resources.

- Minimize access to sensitive data.

- Implement strict shadow IT rules.