Abstract

Along with the use of cloud-based services, infrastructure, and storage, the use of application logs in business critical applications is a standard practice. Application logs must be stored in an accessible manner in order to be used whenever needed. The debugging of these applications is a common situation where such access is required. Frequently, part of the information contained in logs records is sensitive. In this paper, we evaluate the possibility of storing critical logs in a remote storage while maintaining its confidentiality and server-side search capabilities. To the best of our knowledge, the designed search algorithm is the first to support full Boolean searches combined with field searching and nested queries. We demonstrate its feasibility and timely operation with a prototype implementation that never requires access, by the storage provider, to plain text information. Our solution was able to perform search and decryption operations at a rate of, approximately, 0.05 ms per line. A comparison with the related work allows us to demonstrate its feasibility and conclude that our solution is also the fastest one in indexing operations, the most frequent operations performed.

1. Introduction

Business critical applications require monitoring. A frequent pillar of application monitoring is the use of logs. These produce a time-stamped recording of events relevant to a particular system and establish a baseline of standard operations for future reference, to identify erroneous operations, to diagnose performance bottlenecks, to facilitate application debugging, among other tasks. Frequently, part of the information contained in logs records is sensitive. On one hand, when considering on-premises deployment of logging solutions, considerations related to anonymity, confidentiality and integrity of log records may not be addressed. On the other hand, with the advent of cloud platforms that house both the applications and their logs, secure remote logging appears as a crucial issue to address.

Depending on the commercial and trust relations established between a client and a remote log service provider, distinct forms of log storage can be envisioned. If it is the case of storing anonymous logs, these may be stored without additional processing. However, if it is the case of storing application or server related logs that might contain sensitive information on them, these may require encryption to guaranty confidentiality. The log encryption may be performed at the user’s premises or at the premises of the service provider. Additional guarantees, such as integrity or search capability, may also be required. Moreover, if some user related information is comprised in such logs, additional measures are imposed by regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Regulation 2016/679 of the European Union [1]. Finally, a business may wish to deploy its applications with one cloud provider and store the operational logs of those applications in a distinct cloud provider. We envision a Secure Logging as a Service (SLaS) to be one that provides the remote storage of logs with confidentiality, integrity, and searching capability requirements.

When remote log confidentiality is required, the most common solution is to use cryptography techniques to encrypt all data before transferring it to a remote cloud storage service. In some particular cases, the data sent can also be digitally signed to ensure its source trustworthiness, a cryptographic hash can also be computed to assure data integrity and to prevent its manipulation while in transit. If searching within these remotely stored logs is required, the simplest and trivial approach consists of transferring all data back to the client, so that it can be decrypted, allowing search operations to be performed over the clear text and at the client side. Despite the data privacy and confidentiality guarantees offered by this approach and, possibly, data integrity when combined with digital signature and hash validation techniques, it can rapidly become impractical with the normal growth of log data. It will also have a negative impact in the latency and performance of the client-side operations since, every time a search operation is performed, all the log data is transferred to the client. Moreover, this approach does not make use of the full potential of cloud computing.

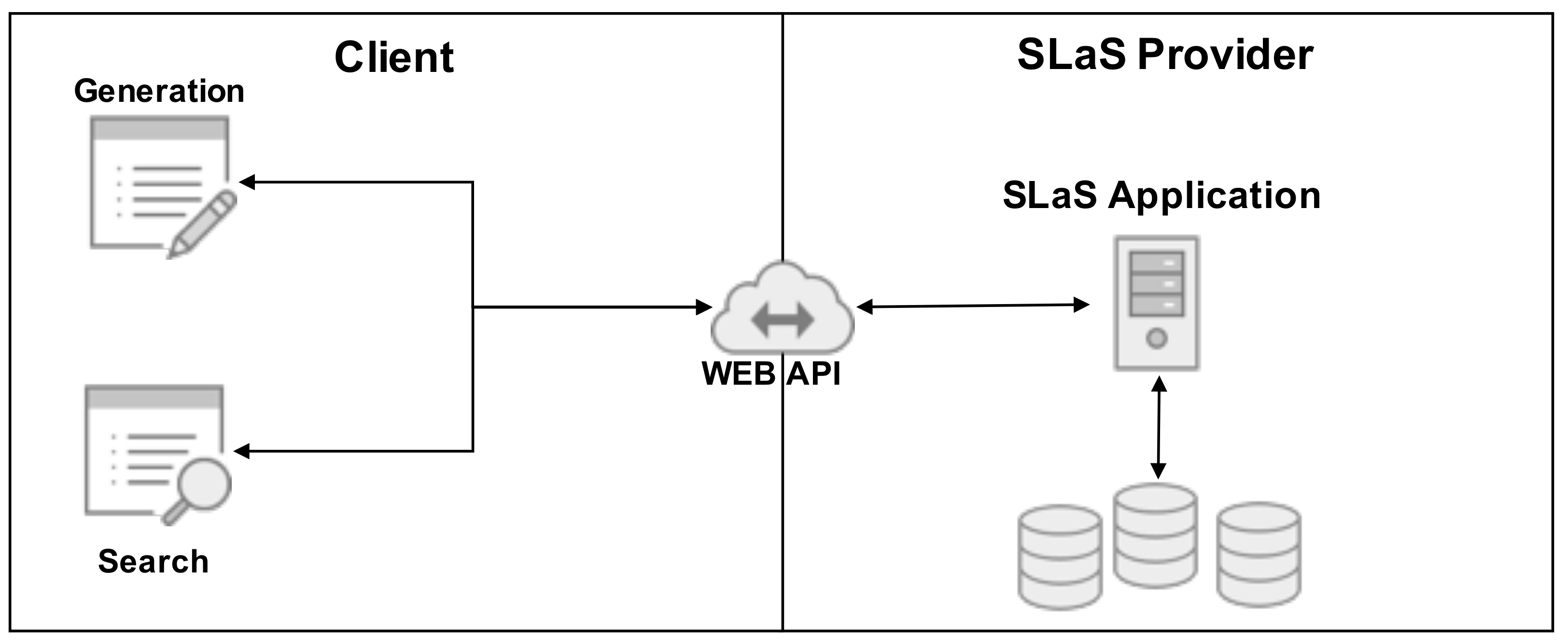

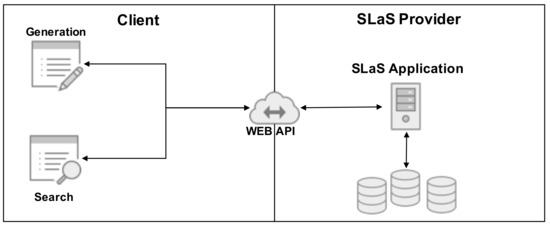

The reference scenario adopted in this work is shown in Figure 1. It describes a cloud-based secure log storage service. The Client makes use of a web-based Application Programming Interface (WEB API) to transfer its encrypted operational logs to the cloud, named SLaS Provider. In parallel, the Client can make use of the same WEB API to query, in a encrypted form, its logs and retrieve matching records. A SLaS application is foreseen in order to make use of the cloud’s potential and to enable the transfer of some CPU-intensive tasks from the Client to the SLaS Provider. The SLaS Provider stores the client-side encrypted logs in its database and performs search operations on them, without having access to clear text logs.

Figure 1.

Reference scenario.

The use of Searchable Encryption (SE) [2,3] was considered. It is a method that encrypts data in such a way that enables keyword searching over the encrypted data, without requiring access to clear text data. To build a more efficient solution, an inverted index was used [4]. The confidentiality of log records is assured not only at rest but also in transit with the use of both symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms. To preserve the integrity of the log lines submitted to the remote storage, the use of keyed hashing algorithms assure that not only the integrity of each log record is preserved but also its authenticity. Moreover, an hash chain is constructed where the successive computation of HMACs makes possible to detect any unauthorized modification in the log sequence.

To the best of our knowledge, the proposed solution is the first one to, cumulatively and efficiently, support:

- confidentiality, integrity and authenticity of the log records;

- efficient log integrity verification; and

- extended search capability by supporting full Boolean searches, plus fielded searching and nested queries.

Moreover, the performed experiments show that the proposed solution outperforms the related works.

This paper is organized in sections. Section 2 introduces SE and overviews its evolution. Section 3 presents all relevant work from other researchers that is related to the one discussed herein. Section 4 details the proposed solution, its architecture and main features. Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 are dedicated to the validation of the proposed solution, a comparison with the related work and its security analysis. Section 8 concludes the work.

2. Secure Remote Storage and Searchable Encryption

The migration of services from on-premises to cloud-based services is becoming a more frequent one. Such service migration implies that data, even if only a subset, must also move to remote storage. This as lead researchers to propose novel solutions for the secure and remote storage of data [5,6]. New research issues appear in this new context, examples being: assuring data confidentiality, maintaining data access, enforcing access control, enabling data sharing, and enabling confidential searching of remotely stored data.

In Reference [7], the authors propose a novel secure cloud storage that makes use of proxy re-encryption to transform remotely stored ciphertexts so that a delegated user can then access them. Similar work, using proxy re-encryption data sharing by means of ciphertext transformation, is presented in Reference [8], this time focusing on IoT. In Reference [9], the authors try to solve the key escrow problem of using a secure remote storage that requires that trusted central authorities be capable of decrypting ciphertexts when needed. In the same line of research, Wang et al. proposed a novel use of Attribute Based Encryption (ABE) to impose fine grained access control to remotely stored data [10]. Other authors pursued the same goal with similar use of ABE [11,12].

The previously described secure remote storage systems focus mainly on protecting remotely stored data, imposing access control or enabling the controlled sharing of the data. These do not support secure remote searching over the remotely stored data. Secure remote searching over encrypted data can then be seen as a different, more specific, research line.

In a clear text remote search operation, the knowledge of both the keywords and the matching data are known to the server. SE arises as a technique that preserves data confidentially while enabling server-side searching [3]. Over the years, various types of constructions have been proposed. In some of them, researchers have focused on the efficiency of SE techniques, while others focused on the security and privacy [13].

Alongside efficiency and security, the expressiveness of queries is the third main challenge within this field of research. In an SE scheme, efficiency can be typically measured by its computational and communication costs. Although there is no common security model, typically, an SE scheme is considered secure if it can assure that the server learns nothing about the queries or the matching results. The query expressiveness defines the types of supported searches, and typically implies some trade-offs, since it generally is achieved at the expense of some efficiency or security.

SE schemes usually operate based on one of two techniques. Some schemes use an encryption algorithm over the clear text data that allows search operations to be performed directly and sequentially on the ciphertext. Thus, the search time is linear to the size of the data stored on the server. Other schemes generate a searchable encrypted index, based on the existing keywords. These indexes can significantly increase the search performance since they allow queries to be performed by the use of trapdoor functions. A trapdoor function consists of a function that is straightforward to compute in one way, but very inefficient to inverse without the knowledge of a secret value. In an SE scheme, these functions are used to generate the search tokens, commonly known as trapdoors, that allow the search to be securely performed. A searchable index can either be a forward index or an inverted index. A forward index builds an index of keywords per document. An inverted index builds an index of documents per keyword [2].

Symmetric Searchable Encryption (SSE) uses symmetric key cryptography and enables only the secret key owner to produce ciphertexts and search queries. Examples of SSE can be found in References [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Public key Encryption with Keyword Search, or PEKS, enable the creation of ciphertexts with a public key, and only the private key owner can perform the encrypted search. PEKS has the particularity of supporting multiple user scenarios due to the fact that anyone can encrypt data with the right public key. Examples of PEKS can be found in References [6,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. More recent example works can be found in References [59,60]. In Reference [59], the authors devise a Lattice-based key-aggregate encryption mechanism. Their work, while being quantum-resistant, only supports the encryption of one bit messages and uses a direct index, where each one bit message will have a associated trapdoor, whereas the work proposed in Reference [60] solves the forward secrecy problem with public key encryption techniques that ultimately result slower operation rates, but also in requiring larger storage space, when compared to symmetric encryption techniques.

3. Related Work

Securing logs is not a new concept since some work can even be found in a pre-cloud era. Bellere and Yee [61] were the first to propose a solution to enhance the security of logs. The authors define a forward integrity security property and demonstrate its application to secure and verifiable logs. Key issues being intrusion detection, accountability and communications security. A forward secure stream integrity is presented and constructed by the use of a forward-secure MACs scheme, in which the log entries are indexed based on time periods. This solution enables a flow integrity of log entries. Based on this work, multiple research efforts appeared.

Schneier and Kelsey [62] proposed a protocol, using symmetric cryptographic, focused on the storage of audit logs. The scheme employs an one-way hash chain [63] used to create a dependency among the log entries. This dependency enables the detection of unauthorized modification in the log sequence since any alteration would break the consistency of the hash chain. An hash chain consists of a successive computation of cryptographic hash functions, where the input of the current hash also includes the output of the previous one. The authors also considered the use of evolving cryptography keys [64] to protect the audit trails and support computer forensics. Evolving cryptography can be seen as an encryption technique in which symmetric keys evolve over time, with the goal of limiting the impact of key compromise. Alongside the communication and storage overhead, since an authentication tag is generated and stored for each individual log entry, the scheme was proven to be vulnerable to truncation attacks. A truncation attack consists of the deletion of tail end log entries without being detected, thereby breaking the log entries integrity.

In 2005, Forte et al. proposed a generic secure logging solution [65] that makes use of covert channels for log transmission. It aims at addressing the lack of security of the syslog protocol [66] with problems related to the transmission of data, message integrity and message authenticity. A covert channel can be used in any communication channel to transmit information using methods not originally though of. The authors explored the possibility of transmitting log data using ordinary DNS requests and responses. They used DNS Security Extensions, asymmetric cryptography, and hash functions, such as the MD5 [67] and the SHA-1 [68] algorithms, considered safe at the time of their publication, to assure messages authenticity and integrity.

Holt et al. proposed Logcrypt [69], a secure logging protocol. Logs are initialized in a known state, stored on an external server, and the integrity of an earlier state can be used to verify the integrity of a later state. The solution provides two different approaches. The simpler one is based on MACs, in which an initial secret random value is used to initialize an hash chain. Each link of the hash chain is then used to derive secret keys for log data encryption. The use of symmetric encryption requires that any entity, who desires to verify the integrity of a log entry, must have the secret key used with the MAC function. Any entity that knows the key can forge log entries and, consequently, break the system’s security. To address this problem, Holt proposed the second approach that uses asymmetric encryption combined with identity-based signatures [70]. Replacing MACs with digital signatures enables the verification of log entries by any entity without disclosing private keys. While the use of asymmetric cryptography simplifies the log entry verification, it creates not only a communication overhead, originated from the constant key pair exchanges between the parties involved, but also a storage overhead since asymmetric key signatures are usually larger than MACs.

Ma et al. [71] proposed a new approach to secure logging. They state that, for an audit logging system to be considered secure, it must assure not only data integrity but also stream integrity, as no reordering of the log entries should be possible. The author also enunciates the log truncation attack, a type of attack that prior schemes [61,62,69] failed to mitigate. The proposed mitigation is based on forward-secure stream integrity. This property is achieved by the use of Forward-secure sequential Aggregate (FssAgg), conceived by the same author in Reference [72]. In a FssAgg scheme, signatures or MACs are combined sequentially into a unique aggregated signature. Based on this scheme, Ma et al. devised two secure logging schemes, one privately verifiable and another publicly verifiable. The privately verifiable scheme is based on MACs, in which two FssAgg MACs are computed over each log file with different keys in order to avoid the dependency of an always online server. The publicly verifiable scheme bases its operation in asymmetric cryptography and is envisioned mainly for systems that require public auditing.

The Secure Logging as a Service (SLaS) term was introduced by Ray et al. [73]. They proposed a novel solution for the storage of log records on a remote server operating in a cloud-based environment. It starts by generating three master keys: and used for data integrity in hash calculations, and used for confidentiality in encryption and decryption operations. These keys are stored based on a proactive secret-sharing scheme [74]. The log records are handled in batches of n, a random value that indicates how many times the master keys can be used. Each batch starts with a special first entry that contains a timestamp and the value n. This entry is encrypted with and a MAC using is calculated over the resulting ciphertext. An aggregated MAC is also calculated using and having each encrypted log entry MAC as input. The closing of the batch is marked by a log close entry, which includes a timestamp and the aggregated MAC. Each log batch is indexed by an upload tag in order to allow for future retrieval of the data. The upload tag consists of an instance of a hashed Diffie-Hellman [75] key. A delete tag is also included.

Zawoad et al. apply SLaS to the digital forensics domain in Reference [76], with a consequent extended version in Reference [77]. They proposed SecLaaS to store logs in a secure way, preserving its confidentiality and integrity, while providing an API for forensic investigators to be able to gather their evidence. The logs entries are encrypted using an asymmetric encryption algorithm. Some of the fields of the entries are kept in clear in order to allow some search operations. After, the log of that encrypted entry is fed to the log hash chain, which is used to maintain the right order of log records. Then, a tuple composed by the encrypted log entry and its matching hash chain link are stored. In order to generate the Proof of Past Log, a publicly available integrity information, one of three accumulator schemes can be used: Bloom Filters (BF), one-way accumulators or Bloom trees. In the BF scheme, a structure is maintained per IP address, per day. The one-way accumulator is a cryptographic accumulator, based on RSA assumption, which enables the test of membership of an element in a set, with no false negatives and the possibility of false positives [78]. Bloom trees arises since BF conceive the possibility of false positives. To build the Bloom tree, for every m number of logs, a new BF is generated, creating BF for n logs records, per IP and per day.

For auditing purposes, Waters et al. proposed a solution [79] that maintains the privacy of the audit logs without losing search capabilities. Each encrypted record is concatenated with the hash of the previous record, forming an hash chain. They propose both an asymmetric and symmetric key schemes for public or private integrity validation, respectively. The symmetric key scheme, inspired by References [14,15], indexes each log entry with the generation of a random symmetric key, that shall be used only for the encryption of each entry. Then, the set of keywords is extracted from the log record. For each keyword , a pseudorandom function is applied having as input and a secret S. The result is then used as input for another pseudorandom function, together with r. The output of this second function is XORed with the key K and a flag, a constant bit string of length l, which yields the final keyword value . The asymmetric scheme is based on Identity-Based Encryption (IBE) [80].

Ohtaki et al. [81] proposed the use of a partial disclosure scheme. Two key pairs are generated and used to compute a log record for both searching and disclosure. The scheme signs each keyword with key . Then, concatenate the signature with the log record unique identifier , encrypting those values together with the public key . The log record is also encrypted with a symmetric key algorithm. After some experiments, Ohtaki noticed that this scheme is inefficient. The use of an encrypted inverted index was then considered to reduce search time. Ohtaki’s inverted index consists of a linear list, on which each list item is composed by the log record identifier and a pointer to the next list item. To assure privacy, these list items are encrypted.

In following work, they proposed an extended solution [82] that supports Boolean queries based on BF. It starts with the generation of all the possible combinations of all keywords that exist in each log entry. For instance, for the keywords “A”, “B”, and “C”, the possible combinations are “A”, “B”, “C”, “A and B”, “A and C”, “B and C”, and “A and B and C”. Next, a normalization is applied to the patterns, making the order of the keywords on the query not important (e.g., “A and B” is the same as “B and A”). The normalized patterns, treated as individual keywords, are encrypted with and concatenated with . The final value is added to the BF.

Sabbaghi et al. [83] proposed a scheme to build an audit log that should guarantee tamper resistance, verification capability, logging speed, search speed and correctness of the search results. They propose the use of a record authenticator generated with hash functions. The schema is focused on SQL commands and starts with the generation of an asymmetric key pair and the sequential publication of the public key . Then, the extraction of keywords from SQL queries is performed. Five groups of distinct types of keywords are created. The first group is reserved for keywords of the “SELECT” part, the second for keywords of the “FROM” clause, the third for keywords of the “WHERE” condition, the fourth group is dedicated to the values of that condition and the fifth, and last group, is used for metadata, such as the time when the query was executed or by whom. Following the creation of such groups, the record authenticator is generated with the use of three hash functions and a dedicated hash space H, which consists on a string of bits, set initially to zero. In order to enhance the security of the scheme, each keyword, prior to its hash calculation, is concatenated with key K. This assures that the same keyword, even on the same group, for two different log records hashes to different places of H.

Accorsi addresses log privacy [84,85] with focus on devices with low resources. His solution, inspired by Reference [62], starts on the device, which is expected to apply the necessary cryptographic techniques to safeguard the privacy, integrity and uniqueness of its log file. Privacy is achieved by encrypting each log entry with a symmetric encryption algorithm. The encryption algorithm also enables forward integrity, meaning that, if an attacker can compromise the log data at instant t, all log data stored prior to t will not be compromised. Integrity is guaranteed by the construction of an hash chain composed by message authentication codes that are calculated per entry and based on a secret random value. Uniqueness is ensured by the use of timestamps, which also prevent replay attacks. Based on References [84,85], Accorsi designed BBox [86], a digital black box that added asymmetric cryptography to guarantee the authenticity of log records. It assures a reliable data origin by only considering log records from legitimate sources. The log records, in order to guarantee forward secrecy, are stored in a encrypted state. Each log is encrypted with a randomly generated key. Tamper-evidence is accomplished through the maintenance of an hash chain. BBox allows single keyword searches, with the use of log views, a mechanism similar to views of relational databases.

Savade et al. [87] proposed a technique to protect log records from tampering based on a system of linear equations, while still permitting search operations to be conducted over those records. The scheme is comprised of four functions: that returns a key pair using a security parameter s; that encrypts a message m, using , and outputs s; that outputs the trapdoor t using m and as input; and a test function that verifies if an encrypted keyword is present in the log records. This verification is conducted using a generalization of the inverse matrix concept [88].

More recently, Zhao et al. address encrypted log searching while preserving privacy [89] using access tickets that are computed using an hash function that contains: the identity and the IP address of the requesting user, the request expiration date, and information regarding the type of operation desired to be executed over the data. This information is then used on the construction of the keyword set that is appended to the encrypted audit log and enables the server to answer each one of the “who/when/where/what” data owner queries. When the data owner desires to query his encrypted audit logs, it creates a trapdoor of the keywords of interest by applying the same algorithm used on the audit log generation. The master keys are used on this generation, assuring that no one besides the data owner can create search trapdoors. Upon receiving such trapdoors, the server tests them against each stored log record. All matching results are returned to the data owner, whom, after assuring the validity and integrity of such results, decrypts them and obtains the information regarding the kind of access that has been done over his data.

Table 1 compares the identified related work. Except Forte et al. [65], whose scheme is focused on the transmission phase, all identified solutions enable privacy by encrypting the data prior to its storage. Boolean search refers to the capability of using the “AND”, “OR”, and “NOT” operators. Almost all solutions enable data integrity and authenticity with the use of a cryptographic hash chain. Only Ma et al. [71] devises a different approach with their specific technique named FssAgg. Regarding encrypted log searching, the solution proposed by Waters et al. [79], although source of inspiration for subsequent solutions, only supports single keyword search and has both high computational and storage costs. The solutions proposed by Accorsi et al. [86] and Savade et al. [87], while being more efficient, only allow for single keyword search. Ohtaki et al. [82] enhances the search capability with support for the “AND” and “OR” operators. Nevertheless, this Boolean queries are achieved not by performing Boolean operations but by adding extra searchable indexes. Ohtaki uses BF that admit the occurrence of false positives, which might disclose more log records than the ones that are relevant. Sabbaghi et al. [83] also supports the Boolean queries with the “AND” and “OR” operators; however, their work is fully focused on SQL commands, hence being only searchable within the SQL clauses. The solution designed by Zhao et al. [89] only allows searches to be performed over the metadata appended to each log record and only to answer the “who/when/where/what” questions. None of the presented solutions supports all the Boolean operators nor support fine-grained operations, like field search and nested queries. Field search can be used to search for a value on a specific part of the log record. For instance, if one wants all log entries from November, fielded search enables the non-occurrence of false positives by not matching log entries that contains the keyword “November” in any other part of the log, except its date. Nested queries can be used, for example, to retrieve log records from the month of November but originating from a specific set of IP addresses. Moreover, none of the solutions proposed in the related work offer all the desired security properties alongside an advanced searching capability.

Table 1.

Comparison with related work.

4. Proposed Solution

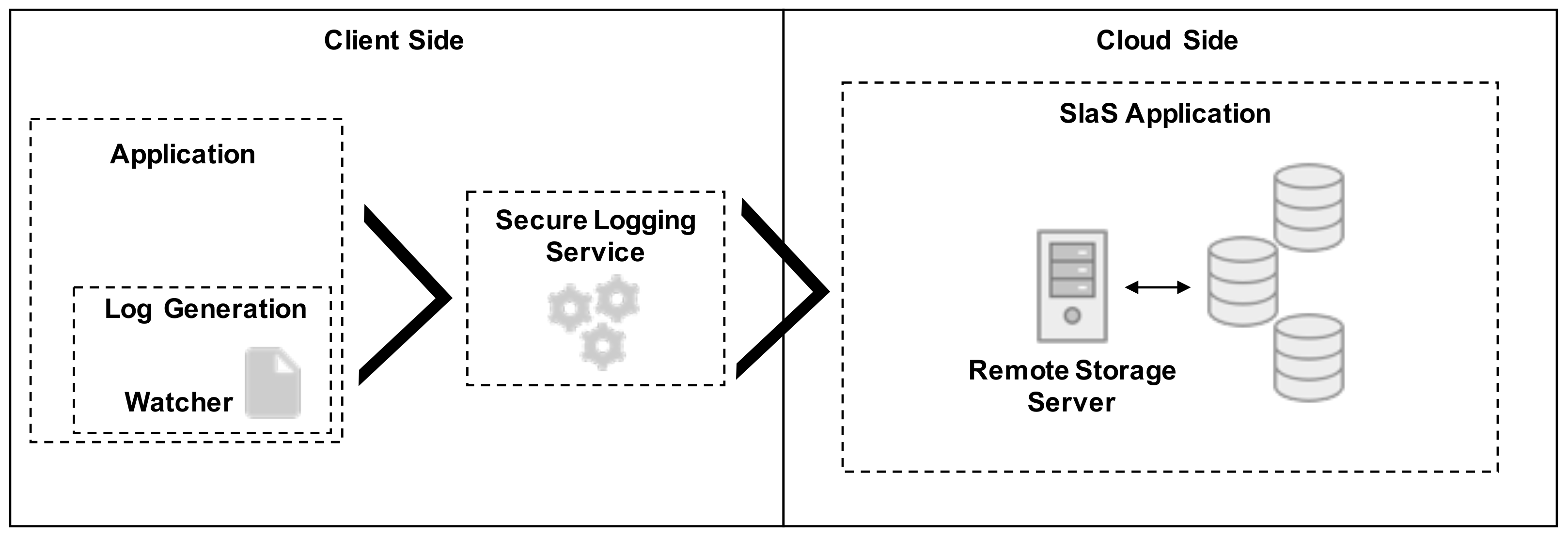

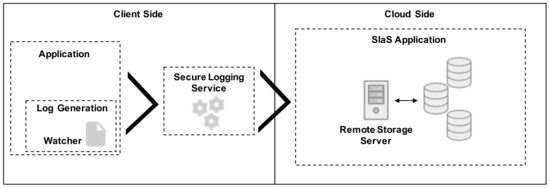

The proposed solution aims to enable remote storage of client encrypted log records, while still permitting search operations to be performed by the remote storage server without having access to the clear log records. The system is physically divided between the client side, where the log records generation occur and the consequent search operations are originated, and the cloud side, where the searchable encrypted log records are stored and retrieved. The client side contains the business applications from which the logs are forwarded to the Secure Logging Service (SLS). These logs, after conversion to searchable encrypted ones, are transferred over to the cloud side. The Secure Logging-as-a-Service (SLaS) application will securely store them on the cloud side. The search operations are also originated on the client side, using the SLS, sent over to the SLaS application, which returns the encrypted matching results to the client side.

The proposed solution is envisioned as a part of a data pipeline, as shown in Figure 2. This pipeline is initialized by harvesting the log records produced by the client applications. Typically, these applications write their operational logs to file; thus, the harvesting of such logs is performed through file watchers. These file watchers serve as plugins for such applications that watch for changes of the log files, raising events every time a new log line is added. The events are then handled by the SLS, that receives clear text log records, transforms them into encrypted searchable data and sends them to the remote storage server. Although the transferred events include log records in clear text, the communication between the file watchers and the SLS is performed through encrypted channels, for which only the two involved parties possess the correct decryption keys and are able to see the information in transit. We assume that all communications between the involved parties are also performed over SSL/TLS connections.

Figure 2.

Flow of data within the pipeline.

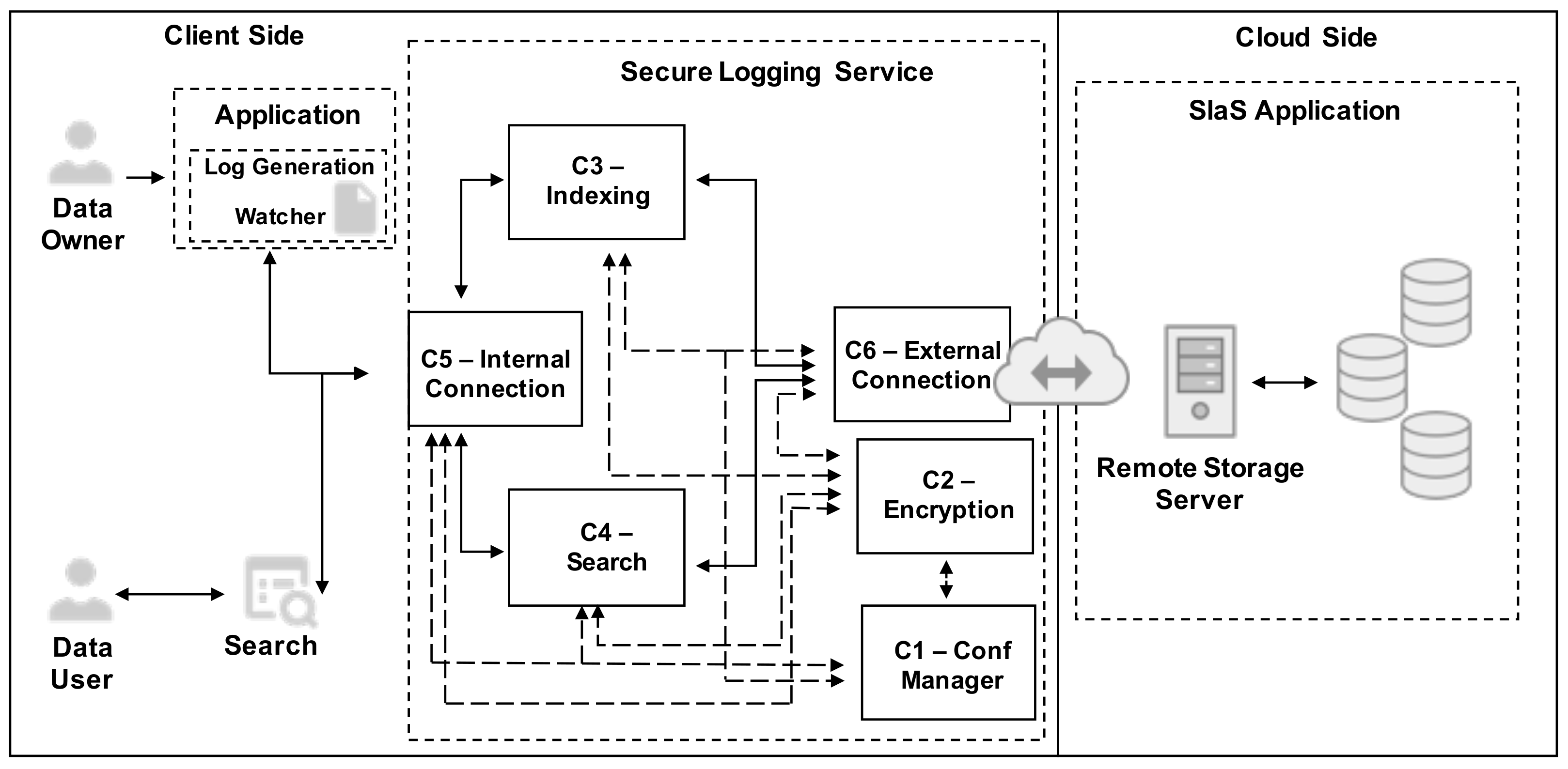

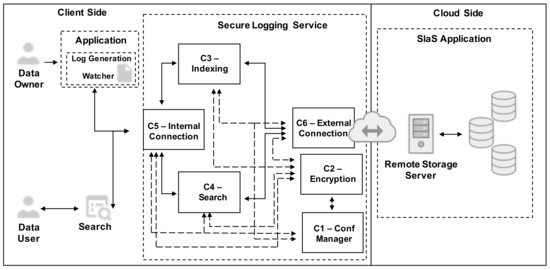

4.1. Architecture

The architecture of the proposed solution is depicted in Figure 3. It is comprised of six components (C1 to C6): the Conf Manager, the Encryption, the Indexing, the Search, the Internal Connection, and the External Connection component. Figure 3 also illustrates, through the use of arrows, the interaction between that components. The filled arrows represent the communication that exists during the two main operations of the solution, namely the indexing and search. The dashed arrows represent the interactions between components required during the execution of that two main operations.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the proposed solution.

The Conf Manager (C1) component is the one responsible for managing all configuration properties of the SLS. Moreover, it is in charge of the secure computation and availability of all cryptographic keys required. We assume that the keys and all the remaining configuration properties are saved on an controlled location, only accessible by the adjacent components using a secure channel. Moreover, we consider that the cryptographic keys always remain in the possession of the data owner and are not shared with any entity external to the described scenario.

The Encryption (C2) component is responsible for all the encryption and decryption operations performed throughout the normal operation of the SLS. Thus, this component acts as a dependency of all the remaining ones. In detail, it collaborates with the Indexing component in order to encrypt all the log records that are sent for storage on the remote storage server. Furthermore, this component decrypts all the information fetched from the remote storage server during search operations.

The Indexing (C3) component is in charge of the transformation of the clear text log records into encrypted and searchable log records. It acts as a proxy, that receives, as input, clear text log records produced by applications, transforms them into encrypted searchable data, and outputs it to the remote storage server that will store it. On the cloud side, the server is not only responsible for the storage of the encrypted log records but also for updating the encrypted inverted index to include the search terms that are continuously being submitted by this component.

The Search (C4) component is the one responsible for submitting queries to the remote storage server and for the retrieval of matching log records. In short, it receives, as input, search terms that are submitted by the client, applies the required transformations to convert them into searchable trapdoors, and, then, submits the transformed search terms to the remote storage server. On the server side, the searched terms are looked up on the encrypted inverted index and the matching log records are returned.

The Internal Connection (C5) component is the only one open to communication with other systems on the client side. In detail, it is accountable for assuring a secure and authenticated communication between the multiple file watchers and the SLS. For every log record submitted for storage, this component will verify the source’s trustworthiness and authenticity. If that validation is successful the Internal Connection component will forward the log record to the Indexing component. The search requests are also originated by this component. If such requests are compliant with the proposed solution security requirements, the Internal Connection will forward the search requests to the Search component.

The External Connection (C6) component represents the bridge between the client side and the cloud side. This component acts as a dependency of the Indexing and Search components since it is the only possible gateway for log records to be stored and search queries to be performed. The External Connection component deals with the complexity of the cloud side connection and ensures the establishment of a secure channel between the two different sides of the proposed solution scenario. Additionally, this component makes the adoption and integration with different cloud providers more seamless.

The proposed solution considers three main operations: Initialization, Indexing, and Searching.

4.2. Initialization

The initialization operation is comprised of two distinct actions. The first is the setup of the SLS itself, and the second is the setup of every source of log records () and its integration with the SLS. We assumed that a source of log records corresponds to a file watcher that only forwards data from one client application.

The setup of the SLS starts by the computation of a pair of asymmetric keys ( and ) to assure a confidential and authenticated communication between the SLS and the SLaS Application. The SLaS Application also computes a set of asymmetric keys ( and ) and performs an handshake with the SLS. This handshake consists of the exchange of the public keys of both entities in order to implement an authentication system between them. Additionally, a symmetric key is randomly generated by the SLS to be used in the trapdoors creation.

The setup of a starts by the configuration of its properties. If the log records follow a fixed structure, thus allowing field searching, a regular expression () can be configured in order to extract specific information from each log record. Alongside, a mapping of the extracted fields () must be added. This mapping includes, for each field, its name and a unique identifier to be used on the cloud side, thus not revealing the type of each field. If the log records do not follow a fixed structure, the SLS will split each log record by a delimiter (e.g., space). Hence, a delimiter () must be configured. Additionally, a set of blacklist characters () is added to allow the SLS to remove unwanted characters and to sanitize the log records prior to its storage.

The following step of a setup is the generation of a unique identifier (). A pair of asymmetric keys ( and ) is generated and will be used to assure confidentiality between the file watcher and the SLS. Then, three symmetric keys are computed. The first key, , is used for the calculation of HMACs that authenticate the file watcher against the SLS. The second key, , is used to compute each log record HMAC, creating an hash chain for integrity and authenticity validations. The third key, , is used to compute an encryption key for each log record. A random seed value is also computed in order to initialize the hash chain. , , and are shared with the file watcher.

In order to support contextual and temporal privacy, either future privacy and past privacy, all relevant cryptographic material will compose a session context. The number of such session contexts and its duration is expected to be specified on a case-by-case basis. For instance, if its the case of a team of developers, within an organization, that are jointly working on a project, the session will be shared between them, and for the duration of the project. If it is the case of a client, a developer and a help-desk technician trying to debug an online service, a specific session context would be created for that purpose. Another case could be the one of a non-critical web application that does not log information with personal data, where a session context could be maintained for longer periods of time. The referred session context is comprised of , , , , , and .

4.3. Indexing

The Indexing operation is carried out by the SLS and per log record sent from the file watchers. The log data undergoes a series of cryptographic operations which transforms it into searchable encrypted information, as described in Algorithm 1.

The first instruction of Algorithm 1 is the attainment of properties (step 1). Next, a unique identifier is generated for log record (step 2). This identifier forms the basis of the computation (step 3), the key specifically used to encrypt the entire log record alongside its timestamp (step 4). Afterwards, an HMAC of the concatenation of , , and is calculated (step 5) in order to maintain both the integrity and authenticity of that specific log record. The obtained is then used to produce the current log record hash chain link (step 6). consists of an HMAC of concatenated with the previous log record hash chain link . is set as the of that , which will be used on the subsequent indexing operations (step 6).

Following, the algorithm moves on to the preparation of the search capability. First, it creates an empty set of trapdoors for that log record (step 7). is populated with one of two ways. If the log record follows a fixed structure, and has a regular expression configured (step 8), the log is parsed by that. If not, the log record is split by a pre-configured delimiter (step 16). More specifically, if exists, for each extracted field of the log record, a lookup operation is performed (step 12) in order to obtain the identifier of such field. Then, the trapdoor for that specific field is built by computing an HMAC, enabling its future search (step 13). Finally, a tuple containing and is added to (step 14). If no is configured, the log record is sanitized by the removal of the characters present in the configured blacklist (step 17) and split by (step 18). Each part of the split log corresponds to a keyword (step 20); thus, for each of that keywords is built by computing an HMAC (step 21), which is then added to (step 22), similar to what is done in the regular expression parsing mode.

This information is, afterwards, transferred to the cloud, being stored by the SLaS Application in its database. Afterwards, the encrypted inverted index , which forms the basis of the forthcoming search operations, is updated. The content of each received trapdoor tuple is analyzed. If includes the field identifier , the entry for the combination of and is affected. If is composed by alone, only the entry for is influenced. In both situations, a verification is executed to find if already exists on . If this verification is successful, the respective is added to the set of the already existing identifiers. If not, a new entry for is created and initialized with the respective .

| Algorithm 1: SLS indexing algorithm | |

| Input: , , | |

| Output: , , , , , | |

| 1 | ← LogSources.get() |

| 2 | ← generateId() |

| 3 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 4 | ← .encrypt([]) |

| 5 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 6 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 7 | ← |

| 8 | ← [] |

| 9 | ifexists()then |

| 10 | ← .parse() |

| 11 | for i ← 0tolength() do |

| 12 | ← |

| 13 | ← .convert() |

| 14 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 15 | .add({, }) |

| 16 | else |

| 17 | ← .sanitize() |

| 18 | ← .split() |

| 19 | for i ← 0 to length() do |

| 20 | ← |

| 21 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 22 | .add({}) |

| 23 | .index(, , , , , ) |

4.4. Searching

The Search operation is assumed to be executed whenever a query over the encrypted log records is required. From the perspective of the user, he submits a clear text query and receives matching clear text log records. However, the SLS applies a series of cryptographic operations to assure that no one besides him has knowledge about the query and matching results. Algorithm 2 explains the process executed by the SLS to transform a clear text query into an encrypted query. Algorithm 3 demonstrates how the SLS, using the encrypted query, retrieves matching log records from the SLaS Application and presents them to the user.

In order to enable the construction of any query supported by the search algorithm, a query syntax was envisioned. Algorithm 2 receives as input a clear text query Q comprised of operators and terms and may be represented like “TERM OPERATOR (TERM OPERATOR TERM)” where the “TERM” represents the keywords to be searched, the “OPERATOR” represents the Boolean operators and parentheses indicate the existence of a nested query. Regarding the OPERATOR clause, the algorithm supports the three basic Boolean operators “AND”, “OR”, or “NOT” that enable conjunctive keyword queries. The TERM clause is used to indicate what keywords shall be searched within the encrypted log records. Each term can be composed either by the single keyword value or by the combination of the keyword value and the identifier of the field where the search should focus. If only the keyword value is present, the query will test the presence of such keyword in any part of the log record, which may return results that are not relevant for the desired search. Thus, the combination of keyword value and the field identifier enables field search and consequent more accurate results. To perform a field query, the field identifier and the keyword value must be combined like “ID=VALUE”. For instance, a query term can be either “GET” or “method=GET”. The former indicates a search of the keyword “GET” in all the log records universe, while the latter indicates that the value “GET” should be only looked up on the field “method”.

| Algorithm 2: SLS query builder algorithm | |

| Input : Q | |

| Output: | |

| 1 | ← [] |

| 2 | ← [] |

| 3 | ← splitQuery(Q) |

| 4 | fori ← 0tolength()do |

| 5 | ← |

| 6 | if isNestedQuery( then |

| 7 | BuildQuery() |

| 8 | else if isOperator() then |

| 9 | .add() |

| 10 | else |

| 11 | if exists() then |

| 12 | ← .convert() |

| 13 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 14 | .add({, }) |

| 15 | else |

| 16 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 17 | .add({}) |

| Algorithm 3: SLS search algorithm | |

| Input : | |

| Output: - | |

| 1 | ← .search() |

| 2 | forn ← 0tolength()do |

| 3 | ← |

| 4 | ← LogSources.get() |

| 5 | logVerified ← HMAC.verify(, , ) |

| 6 | if logVerified then |

| 7 | ← HMAC.create(, ) |

| 8 | ← .decrypt() |

| 9 | .print() |

5. Validation

A prototype of the proposed solution was implemented using version 12.6.0 of the NodeJS runtime environment. All cryptographic operations used the crypto native module, which provided methods to implement the solution with secure cryptographic algorithms. The tests performed used the AES algorithm in the GCM scheme [90]. The HMAC computations were based on the SHA-3 algorithm [91]. The asymmetric cryptography applied on the communication phase used the RSA [92] algorithm. In terms of hardware, the prototype was executed on a computer running Linux with an Intel Core i7 4700MQ 3.4Ghz processor and 8GB of DDR3 RAM memory. For storage, both a single instance of a MongoDB and a PostgreSQL database servers were adopted. Moreover, during the prototype development, we assume the existence of a single log source.

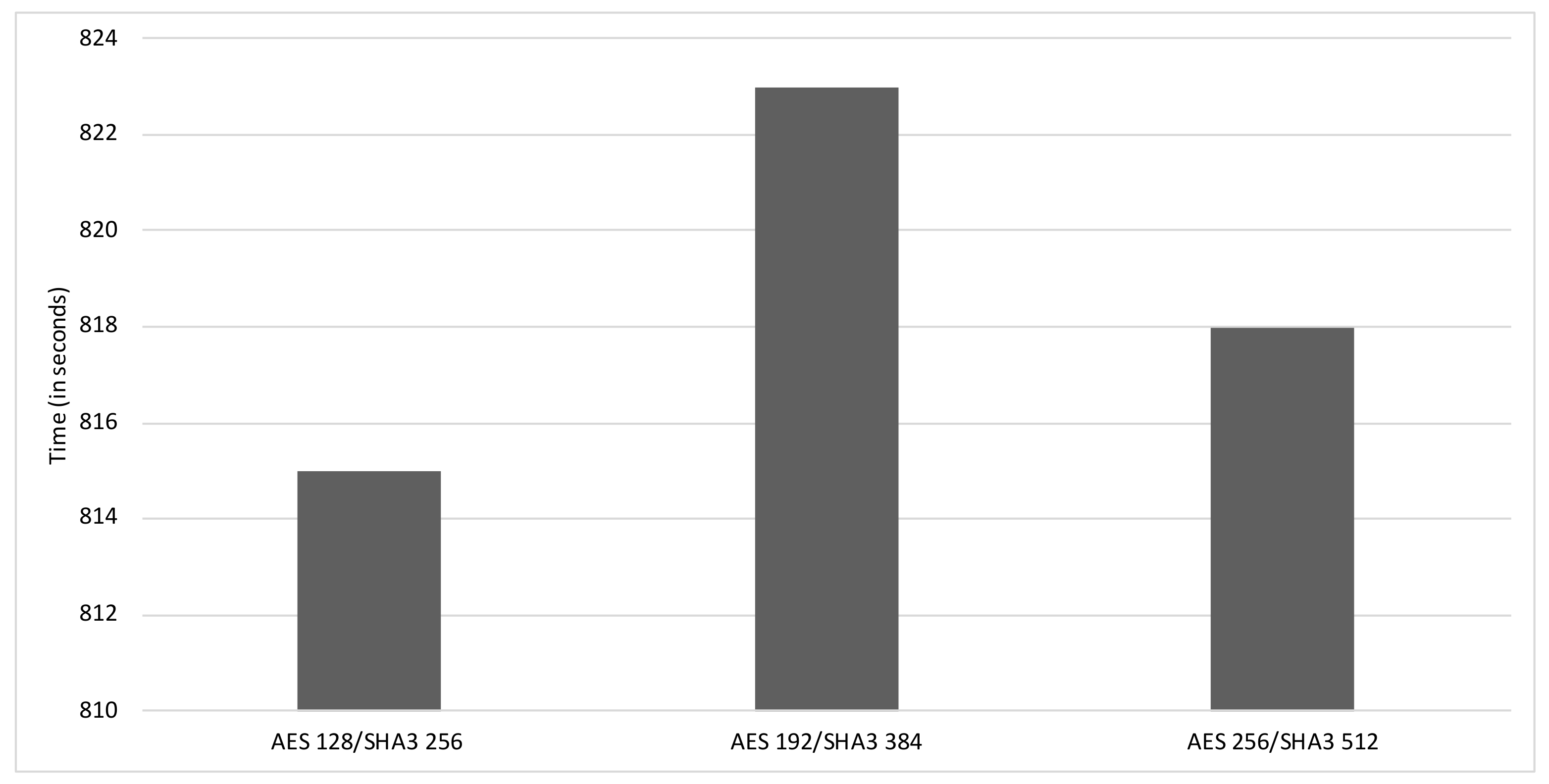

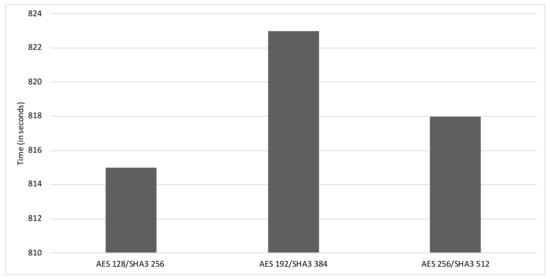

The performance tests were executed using a real-life access log from a publicly accessible web server with, about, thirty thousand (30,000) records per day, on average. Despite the fact that the proposed solution supports any type of log files, this log was select due to being readily available. The average number of records per day was calculated from a period of three weeks. The log files were segmented by day and the number of log records per day was counted and then averaged. The tests were performed using a combination of different key sizes for the two algorithms used in indexing and searching operations. Experiments were performed with AES with 128, 192, and 256 bit size keys and SHA-3 with 256, 384, and 512 bit size keys. For the RSA keys, since it was only applied on the communication between the SLS and SLaS Application, a unique size of 2048 bits was used. In particular, tests were carried out with the following combinations: AES 128 and SHA-3 256; AES 192 and SHA-3 384; AES 256 and SHA-3 512. In each experiment, three test runs per each key size combination were carried out and the average values presented.

The first set of tests focused on time elapsed for the indexing of the 30,000 log records and the storage space it required when using multiple combinations of keys sizes of the AES and SHA-3 algorithms. As illustrated in Figure 4, when using the minimum key sizes of 128 bits for AES and 256 for SHA-3, the proposed solution can index the required log entries in 815 s. The medium key sizes of 192 bits for AES and 384 for SHA-3 are the ones that take longer, demanding 823 s. When using maximum key size of 256 bits for AES and 512 for SHA-3, the proposed solution takes 818 s (roughly 13 min) to do the same operation. If we consider that a day is comprised of 1440 min, we can conclude that the solution, when using the maximum key sizes for each algorithm, which at the time of writing is considered safe, takes about 0.9% of a day to securely store the log entries generated on that day. Moreover, it is appropriate to notice that the disparity between the elapsed times of the different key combinations is small, as expected by the use of symmetric cryptography. Thus, it is possible to use the biggest key sizes for each algorithm, guaranteeing a higher level of security without compromising the performance of the solution.

Figure 4.

Time required to index 30,000 records, per key size.

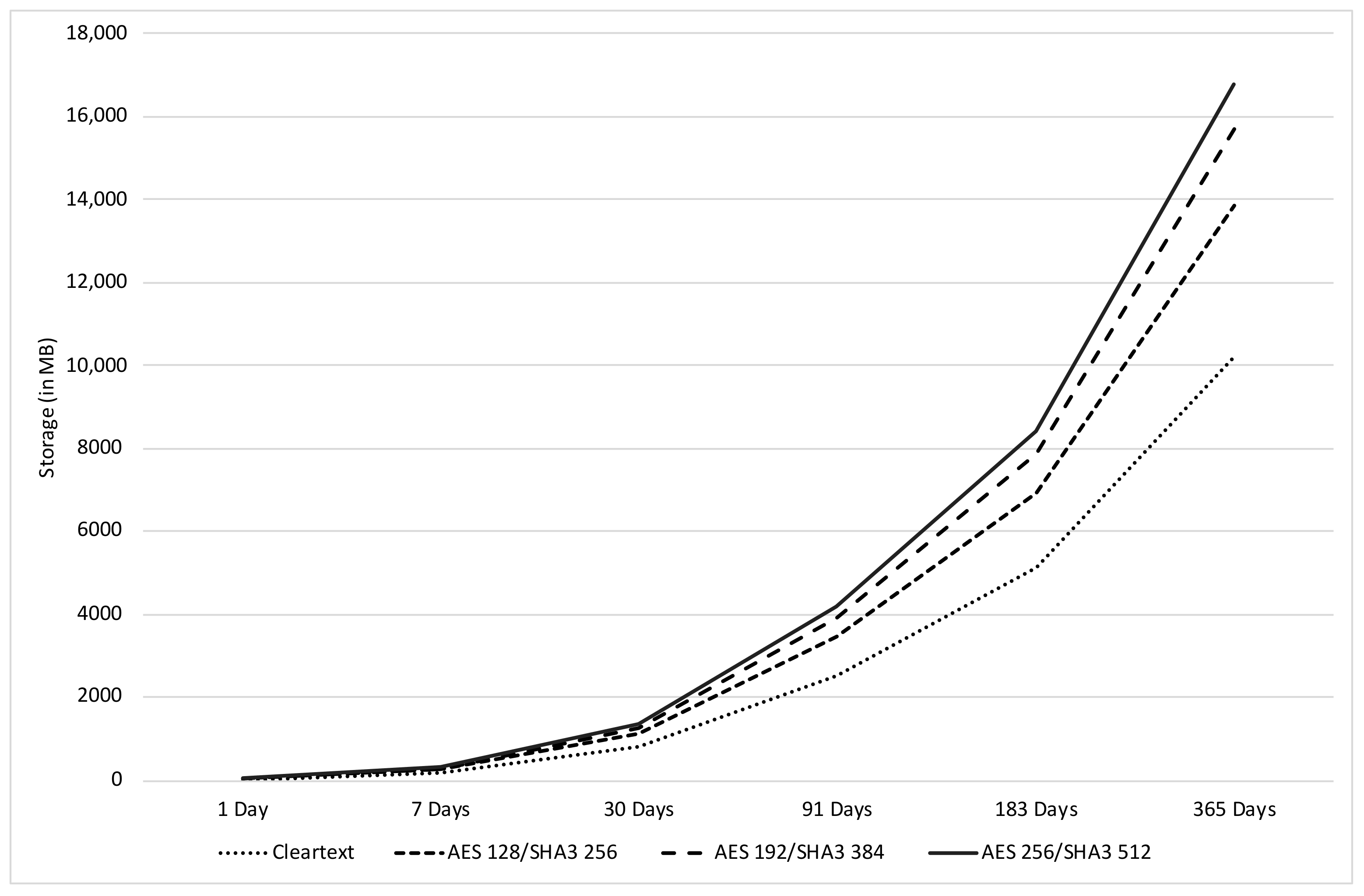

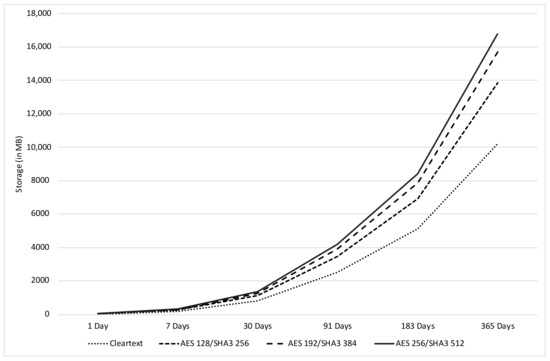

Regarding the storage space requirement, without any encryption or keyed hashing operations, the proposed solution uses an aggregate total of 28 MB. For the minimum key sizes, the proposed solution uses 38 MB. When using 192 bit size keys for AES and 384 bit size keys for SHA-3, the solution requires a storage space of 43 MB. When using the maximum key sizes for each algorithm, both the inverted index and the log records occupy a total of 46 MB. With those values, it is possible to denote a very small discrepancy between the different tested key sizes combinations. Additionally, it is interesting to see that the required stored space for the clear text inverted index is very similar to the encrypted ones. Regarding the database required space, the clear text version occupies less since the log record is stored without no encryption and with no inclusion of its hash value and hash chain link. A projection, depicted in Figure 5, of the required space for the storage of log records generated up to a period of one year was performed. The numbers show that, if the log records are stored in clear text, roughly 10 GB of storage space is required for one year. When using the smallest key sizes for both algorithms, roughly 14 GB of storage space is required for one year. When using medium key sizes, almost 16 GB of storage space is required for the same period. When using the biggest key sizes, roughly 17 GB of storage space is required for the same period. Based on the values projected in Figure 5, it is possible to conclude that, if 256 bit size keys are used for AES, and 512 bit size keys are used for SHA-3, an additional 30% of space is required when compared with the clear text version. Although the percentage achieved is larger than expected, we consider that the impact on the required storage of using encryption and keyed hashing with the biggest keys does not outweigh the increase in security.

Figure 5.

Storage requirements per key size.

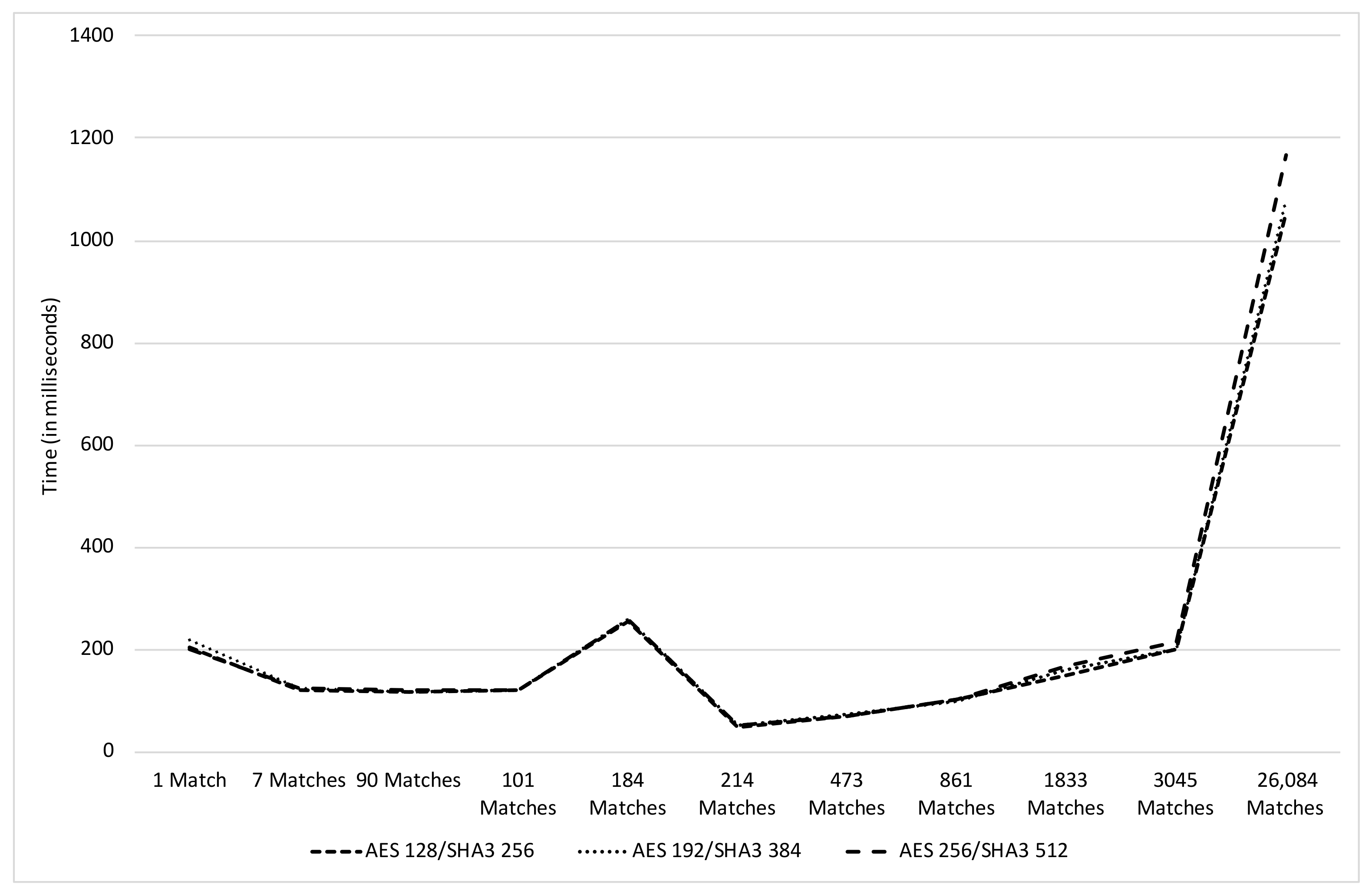

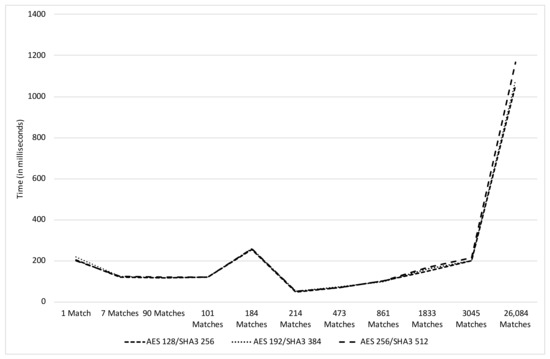

Performance tests of the search operations were also executed. The tests were executed with the same combination of algorithms, key sizes and techniques used on the indexing of the sample 30,000 log entries. For each key size, several search terms were tested. These search terms would return different numbers of matching log lines. The times shown in Figure 6 are the sum of both the time elapsed for the search conducted by the SLaS Application and the consequent data decryption executed by the SLS. Analyzing the results, we can conclude that the different keys sizes do not influence the speed of the search and decryption operations, being possible to achieve similar results in all the tested combinations. This behavior was somewhat expected since the symmetric cryptographic algorithms performance is not heavily influenced by the used key sizes.

Figure 6.

Searching times per key size and matches.

Then, we can denote that the time used in search operations does not grow linearly to the number of matching results. For instance, to obtain the clear text result of a search operation that returned 3045 encrypted log lines, representing roughly 10% of all log records, the proposed solution took about 200 ms. Other search operations, such as the ones returning 3000 or less matches, were executed with an approximate average time of the same 200 ms. Lastly, it is important to consider the values achieved on the search operations that returned 26,084 matches, representing roughly 87% of all the log records. The proposed solution was able to process this result in a time below 1.2 s. Based on that, it is possible to estimate that, in order to search and decrypt all the 30,000 log records, the solution would take less than 1.5 s.

6. Comparisons with Related Work

A comparison with the solutions identified as related work is interesting in order to validate where our solution fits in terms of performance and storage requirements. Moreover, only the solutions that have the ability to search within the encrypted data were analyzed since these were the ones that were deemed equivalent, with respect to their basic functionality, to the one proposed herein.

The first conducted observation is related to the number of cryptographic operations required for the index and search operations, which is useful to measure the distance between the computational cost of our solution and the ones in the related work. Table 2 depicts the number of cryptographic operations for both indexing and searching, where represents a symmetric encryption operation, represents an asymmetric encryption operation, represents a symmetric decryption operation, represents an asymmetric decryption operation, H represents an hash operation, K represents the number of keywords, and N represents the number of matching results in a search operation. The formulas presented in Table 2 represent the computational cost to index one log record and to perform one search operation.

Table 2.

Comparison of indexing and search operations.

Analyzing Table 2, it is possible to denote that the solutions of Waters, Ohtaki, and Savade only require encryption operations on indexing. The first uses 1 symmetric encryption plus 2 asymmetric encryption operations for each keyword K, the second uses 1 asymmetric encryption alongside symmetric encryption operations, and the third uses 1 asymmetric encryption plus an additional asymmetric encryption for each K. Our solution only requires 1 symmetric encryption operation to index a log record. Additionally, our solution needs 3 hash operations plus a new hash operation for each K. The remaining solutions that also use hash operations for indexing are Sabbaghi, Accorsi, and Zhao. The first and the third use 3 hash operations per each K, and the second uses the same number of hash operations as our solution.

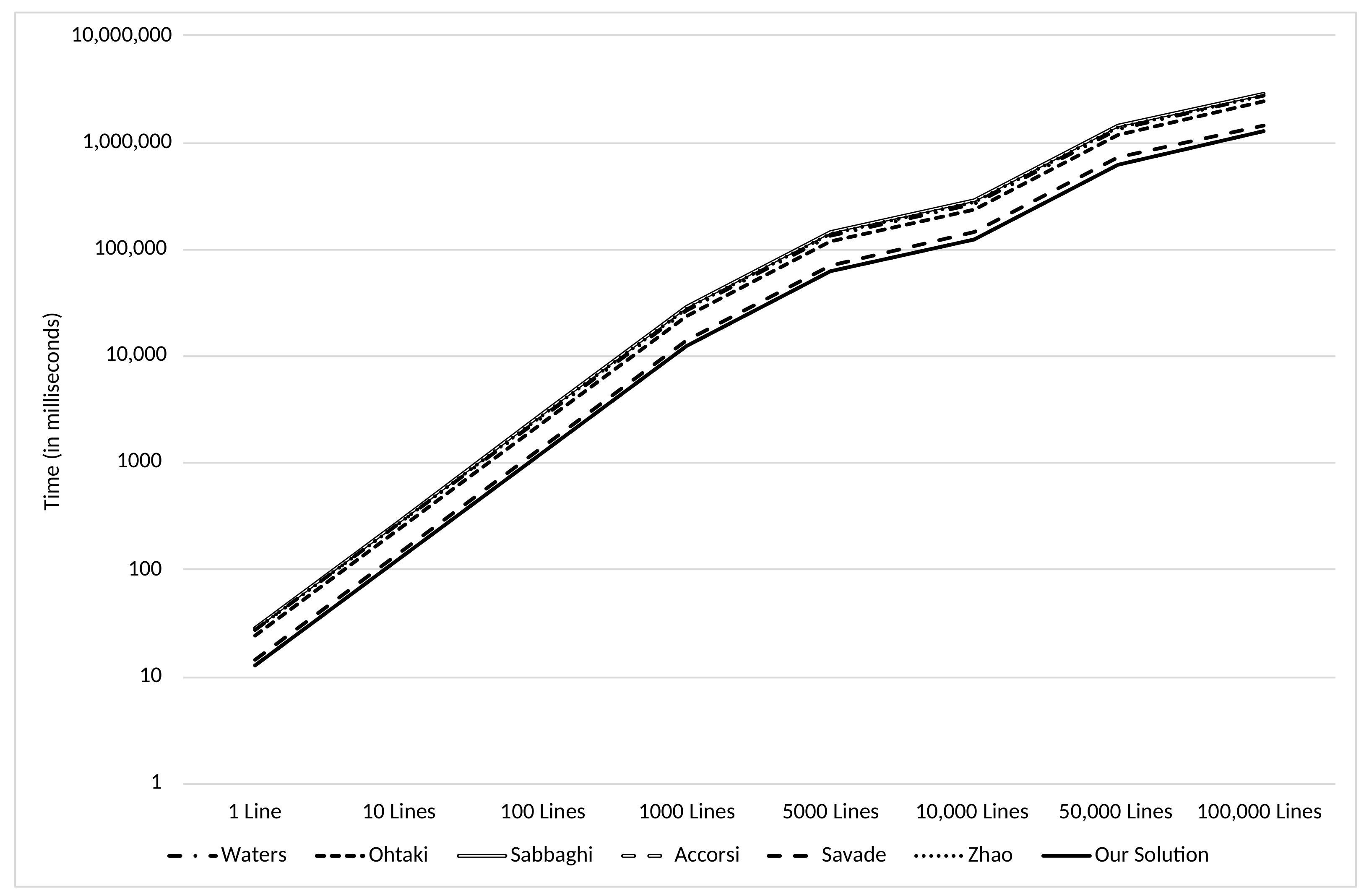

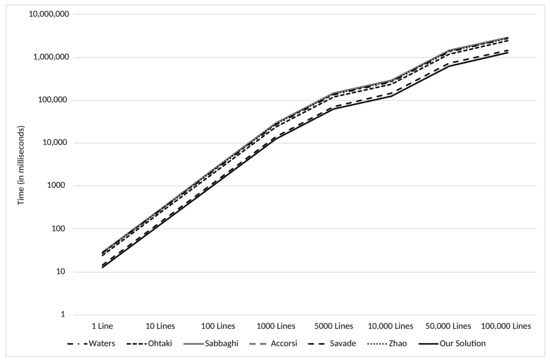

Based on those values, a projection of the time required to index various numbers of log lines on the multiple identified solutions was made. In order to perform it, average values of times elapsed for the cryptographic operations were necessary. Such values were obtained by running 50 tests for each operation and then calculating the average elapsed time for each one. Based on that, it is possible to assume that an hash operation takes 0.88 ms, a symmetric encryption operation takes 1.08 ms, a symmetric decryption operations takes 1.50 ms, an asymmetric encryption operation takes 1.30 ms, and a symmetric decryption operations takes 1.75 ms. Figure 7 depicts the indexing projection from 1 to 100,000 lines. A value of for the number of keywords present in each log line was assumed. This is, each log line is comprised of 10 keywords that must be indexed. Figure 7 uses a logarithmic scale. Based on the values presented, it is possible to conclude that the computational cost of the indexing operation our solution is equal to the lowest one (Accorsi).

Figure 7.

Comparison of indexing times.

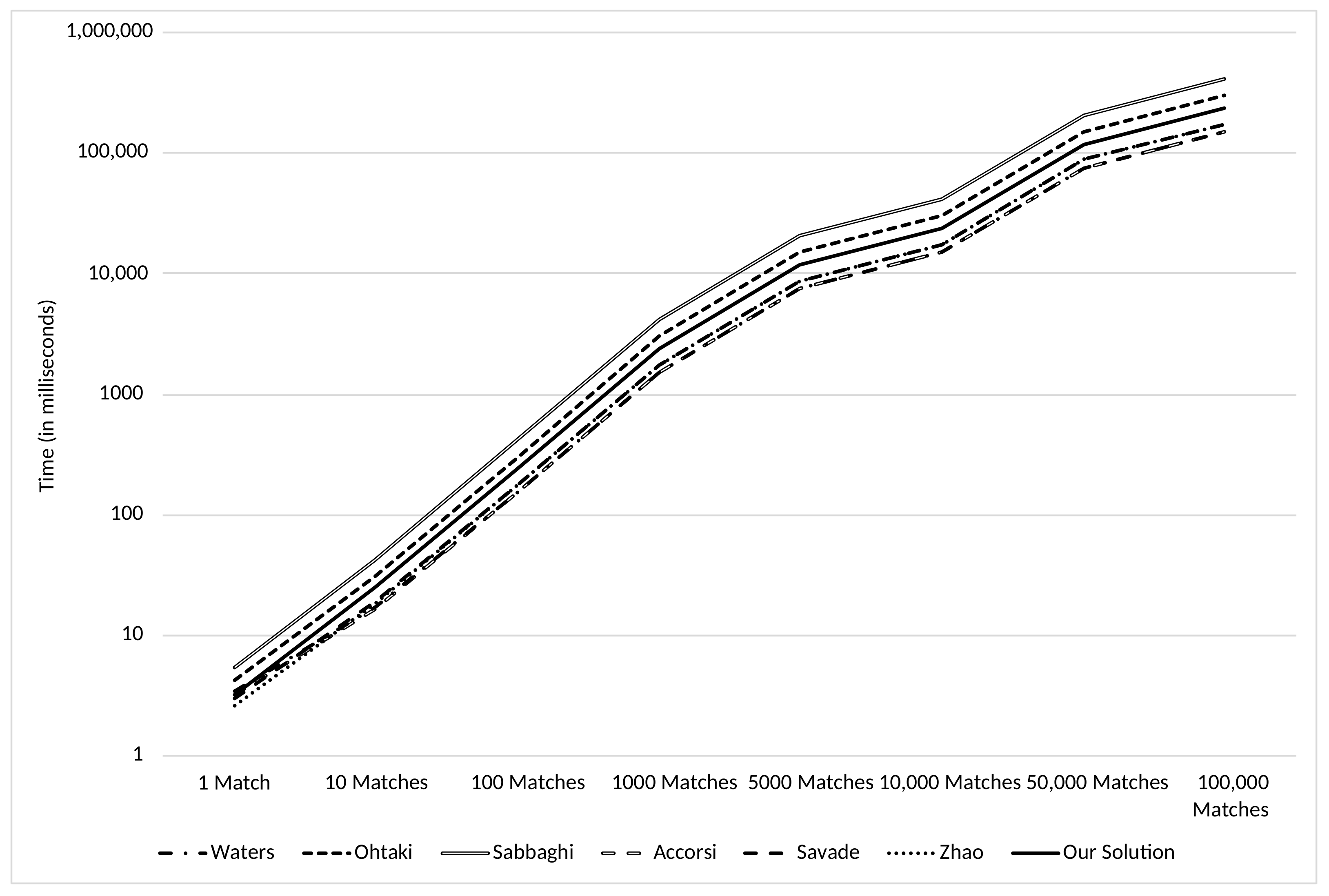

Regarding the number operations required in search operations, our solution does not require any encryption operation, unlike the solutions of Waters, Ohtaki, Sabbaghi, and Savade. The first uses 2 asymmetric encryption operations per keyword K, the second and the third use a single asymmetric encryption operation, and third uses 1 asymmetric encryption operation per keyword K. Hash operations are used by Sabbaghi, Accorsi, and Zhao. The first uses 3 hashes per each keyword K and number N of matched log records, and the second and the third use K hash operations. Decryption operations exist on all solutions. Except Ohtaki, which requires operations per each K, all solutions use a single decryption operation per N number of returned log records. Waters, Sabbaghi, and Accorsi use symmetric encryption, while Savade and Zhao use asymmetric encryption. The proposed solution requires 1 hash operation per each keyword K, plus an hash and symmetric decryption operation per each number N of matches log records.

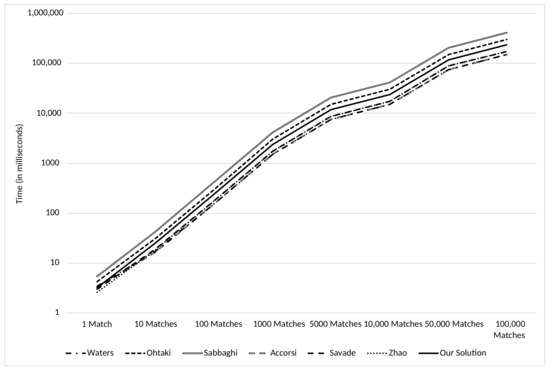

A projection of the time required to search and decrypt various numbers (N) of matching results was also done (see Figure 8). This projection uses the same time values for the different cryptographic operations as the ones used in the indexing projection. Additionally, a value is assumed for the number of keywords comprised in the search query. Figure 8 uses a logarithmic scale. It shows that solutions with lesser computational cost, compared to the proposed solution, exist. Nonetheless, the performance of the proposed solution was deemed acceptable since the level of search enhancement achieved outweigh the differential computational cost of the search operation. We denote that the search operation is the least frequent one and that our solution still obtains an average performance on these operations.

Figure 8.

Comparison of searching times.

A second comparison motivated by the analysis of the validation sections of the related work was also performed. This comparison is focused on the storage and time requirements for both index and search operations present on the validation sections of the related work. Nevertheless, not every author whose work supports search is referred to in this comparison due to the lack of information regarding that type of testing on their solutions.

The solution proposed by Waters [79] presents some information regarding the storage space requirements. The author states that a 100 MB storage is capable of storing 800,000 public keys that correspond to 800,000 keywords. The space needed to store the encrypted log records is not addressed. Our solution requires, for the maximum key sizes (256 bits for AES, 512 bits for SHA-3), a storage space of 23 MB for the inverted index. Regarding the indexing elapsed times, Waters states that, for each keyword, his solution requires 180 ms to compute its trapdoor, if that trapdoor is not already in a cache. If it is present on a cache, this operation takes 5 ms. If we consider the 30,000 sample log records used on the performance tests and that only one keyword exists per log record, Waters solution would require roughly 25 min to index the keywords, considering a 5 ms time per keyword. Our solution was capable of indexing the 30,000 sample log records, which contained more that one keyword per log record, in under 15 min.

In terms of searching, the solution proposed by Waters demands a time of 81 ms to execute the required search operations for each entry. Although, when searching for one singular entry, Waters solution is faster than our solution, when searching for multiple entries, our solution becomes faster since it does not follow a linear growth of the time elapsed for searching operations.

Ohtaki’s first solution [81] only presents details regarding searching times. His solution depends on the number of records in the entire log sample and presents a search time almost linear to the number of matching records. Thus, although Ohtaki’s solution presents faster search times for smaller number of matching records. Our solution is not affected by the size of the entire log record and presents faster search times for bigger numbers of matching records. For instance, our solution requires an average value of 200 ms to retrieve 3045 matching records and Ohtaki’s solution takes 742 ms to obtain 1007 matching records in a universe of 100,000 log records. In Ohtaki’s second work [82], which uses Bloom filters, the author states that, for each log record entry, a 2.6 MB storage is required for a set of twenty keywords. If such scheme was applied to the sample 30,000 log records, a 78 GB storage space would be needed, in contrast to the 23 MB required by our solution, to store the inverted index. Times used in indexing and searching operations were not detailed by the authors in their work.

Sabbaghi [83] presents tests for various numbers of stored log records, which indicate that his solution is affected by the existing total number of logs. For instance, in order to perform a search within 400,000 log lines his solution would take roughly 20 s (0.05 ms per line) with a fixed length hash space and roughly 40 s (0.1 ms per line) with a variable length hash space. Our solution was able to perform a search and decryption operation of 26,084 sample log lines in about 1.2 s (0.046 ms per line). If we assume an expected linear growth of the proposed solution on the time consumed to perform the search, it is possible to estimate that, for the 400,000 log lines, the proposed solution would require 18.4 s to search through and decrypt all lines. Regarding the storage size required, Sabbaghi’s solution needs roughly 20 MB to store the searchable record authenticator when using a fixed length hash space, and about 50 MB when using a variable length hash space. Our solution requires 20 MB to store the encrypted inverted index using 128 bit size keys for AES and 256 for SHA-3 and 23 MB using 256 bit size keys for AES and 512 for SHA-3.

Accorsi, in Reference [86], presents information regarding the times elapsed for the validation of the log records forward integrity. The author presents different values for multiple numbers of log entries. For instance, in order to verify 3000 log records, his solutions requires roughly 950 ms. Our solution achieved an average value of 300 ms to verify the forward integrity of the 30,000 sample log records.

This comparison shows that the proposed solution is feasible. Regarding the times elapsed in indexing, searching and verification, our solution outperforms all related work that presented performance results in their work. Regarding storage size, our proposed solution also achieves the lowest storage requirements.

7. Security Analysis

Our proposed solution has to accomplish security. In general, this requirement is comprised of: indexing and query confidentiality and privacy. Moreover, it is necessary to prevent leakage due to index information, leakage due to search patterns, and leakage due to access patterns.

Index information leakage refers to the keywords that comprise the encrypted searchable index. Search pattern leakage consists of the information that can be derived from knowledge of whether two search results are from the same keyword, revealing that the same search was already performed in the past or not. The use of deterministic techniques for trapdoor generation directly leaks the search pattern since the remote storage server may use statistical analysis and infer information about the query keywords. This requirement is known as predicate privacy [28]. Access patterns can be described as the set of search results (i.e., the collection of documents) that were obtained for a given keyword. This type of information might aid an attacker to learn information about the keywords since the remote storage server will always return the same set of encrypted documents for the same encrypted keywords. In practice, the leakage of search and access patterns can be reduced but not totally eliminated [13].

7.1. Threat Model

In scientific literature, there is no standard security model regarding solutions based on searchable encryption [93]. The adopted threat model assumes an honest-but-curious server that faithfully follows the protocol, but it is eager to learn confidential information by analyzing the received encrypted log records, search queries and matching results in order to obtain information about the content of those log records. Moreover, we assume the existence of external threats. Respectively, we consider that an attacking agent may read, alter or delete data, not only at rest but also in transit. Based on that, we focus on the protection against violation of privacy and integrity, data leakage, replay attacks, unauthorized access and spoofing. Additionally, the proposed solution must offer protection against two of the most common referred attacks in the searchable encryption field, these being the Chosen-Keyword Attack (CKA) and the Known Keyword Attack (KGA).

A CKA attack occurs when an attacker gathers knowledge about the stored information by obtaining the decryption of chosen keyword ciphertexts. In other words, the attacker chooses an encrypted keyword and is handed the corresponding keyword in clear text. To assure the confidentiality of the keywords, the searchable encryption scheme must be Semantically Secure under CKA (SS-CKA) [57]. In an SS-CKA scheme, an attacker cannot learn information about the keywords that are present on the stored ciphertexts, if that keyword is not known to the server. A KGA attack can be performed on a searchable encryption scheme if the ciphertexts of all keywords were produced by the attacker. By knowing one trapdoor, an attacker can search the remaining ciphertexts for corresponding results. If the ciphertext that contains the keyword is found once, an attacker can guess the keyword that is correlated to the trapdoor. This type of attack is more frequent when the keyword space is small since the attacker can rapidly generate ciphertexts for of all keywords [94].

It also important to assert that this security analysis was inspired by the security definitions brought by Curtmola [17]. He pointed out that the security of both the indexes and the trapdoors are inherently linked, introducing two security notions, Non-adaptive security against CKA (IND-CKA1) and Adaptive security against CKA (IND-CKA2). This two definitions state that nothing should be leaked from the remotely stored documents and searchable index except the outcome of previously searched queries, providing security for trapdoors and assuring that the trapdoors do not leak information about the keywords, except for what can be inferred from the search and access patterns [2].

7.2. Analysis

Prior to the analysis itself, it is important to denote that we assume that all cryptographic keys are saved on controlled locations, always remain is the possession of their owners and are not shared with any unauthorized entity.

The indexing operation of the proposed solution must assure privacy and integrity of the data at rest, but also index confidentiality and data leakage prevention due to index information must be accomplished. The data privacy at rest is given by the symmetric encryption of each log record prior to its transmission to the SLaS Application. Integrity comes from the computation of an HMAC based on the encrypted log record , its identifier , and its log source identifier . Additionally, each log record is used on the construction of an hash chain. This hash chain links the log records in such way that makes it possible to detect any unauthorized modification or deletion.

The index confidentiality is assured since every keyword trapdoor that is to be added to the searchable index is computed, at the client side, through an HMAC, using a secret key that is only known by the SLS; hence, no entity other than itself is able to generate trapdoors. Moreover, since an HMAC is a one-way function, it is unfeasible to an attacker to obtain the original keywords even if he has access to the trapdoors. Additionally, in order to enable field searching, alongside the keyword trapdoor, the SLS might include the type of each field. Each field name is mapped to a unique identifier and the unique identifier is then used, which hides the type of each field to the SLaS Application. Lastly, since every cryptographic operation necessary is performed at the client side, the possibility of data leakage due to index information is eliminated.

At the search phase, the proposed solution must assure prevention against leakage due to search patterns and leakage due to access patterns. Moreover, it must be resilient against CKA and KGA attacks. Since the creation of the search capability uses deterministic techniques for trapdoor generation and the SLaS Application has knowledge about the search results obtained for a given keyword, our solution is in part vulnerable to search and access patterns leakage. However, that leakage is only made to the SLaS Application since the confidentiality of the search queries and consequent matching results is assured in transit by the TLS/SSL tunnel. Additionally, based on that leakage, the SLaS Application is only able to produce statistical information about the search activity since the plaintext content of both the search queries and the matching log records is preserved. In detail, search queries are built by one-way functions; thus, only a brute-force attack would be able to obtain the plaintext of that queries. The matching log records are symmetrically encrypted and decrypted at client side; thus, only the SLS is able to see the plaintext of such log records. Moreover, while designing the proposed solution, we assumed that the benefits of constructing a more advanced and expressive query engine outweigh the search and access patterns leakage to an honest SLaS Application. In practical terms, we assumed that entities contract cloud services with providers that they have established some degree of trust.

Regarding CKA attacks, the proposed solution is not vulnerable since, in order to be able to perform such action, an attacker must gather knowledge about the stored information by obtaining the decryption of chosen keywords. Our solution makes use of HMACs to build the query trapdoors. Since HMACs are one-way functions produced with a secret key, always in possession of the SLS, it is unfeasible for an attacker to obtain the original content of chosen trapdoors. KGA attacks are only possible if all the ciphertexts of all keywords were produced by the attacker. Since the SLS is the only entity able to generate keyword trapdoors, the proposed solution is also secure against KGA attacks. Regarding the IND-CKA1 and IND-CKA2 security definitions, the proposed solution is compliant with both since the security of trapdoors is assured, and the only conceivable leakage is of the search and access patterns to the SLaS Application.

8. Conclusions

In this work, we present a novel solution that enables a secure, confidential, and off-premises storage of encrypted log records. The solution allows searches to be performed by the remote storage server without it having access to the clear log records. To do so, we leverage the use of searchable encryption and of an encrypted inverted index. The implemented prototype and the obtained results demonstrate that the proposed solution is feasible, using off-the-shelf hardware, and that it outperforms related work and includes searching capabilities, such as full Boolean queries, field searching, and nested queries, which are not present in related work. In the future, we plan to extend this work into a platform to enable the debugging and execution of web/cloud applications with privacy and confidentiality requirements that are developed by cooperating teams in real time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P. and R.A.; methodology: A.P.; software: R.A.; validation: A.P. and R.A.; data curation: R.A.; original draft preparation: R.A.; review and editing: A.P.; supervision: A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Norte Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), within project “Cybers SeC IP” (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000044).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Voigt, P.; Von dem Bussche, A. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bösch, C.; Hartel, P.; Jonker, W.; Peter, A. A survey of provably secure searchable encryption. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2015, 47, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Secure searchable encryption: A survey. J. Commun. Inf. Netw. 2016, 1, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, J.; Moffat, A. Inverted files for text search engines. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2006, 38, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ren, K.; Cao, N.; Lou, W. Toward secure and dependable storage services in cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2011, 5, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Bellare, M.; Catalano, D.; Kiltz, E.; Kohno, T.; Lange, T.; Malone-Lee, J.; Neven, G.; Paillier, P.; Shi, H. Searchable encryption revisited: Consistency properties, relation to anonymous IBE, and extensions. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, P.; Choo, K.K.R. A new kind of conditional proxy re-encryption for secure cloud storage. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 70017–70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Liyanage, M.; Braeke, A.; Kanhere, S.S.; Ylianttila, M. Blockchain based Proxy Re-Encryption Scheme for Secure IoT Data Sharing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC), Seoul, Korea, 14–17 May 2019; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur Sandor, V.K.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, F.; Zhang, S. Efficient decentralized multi-authority attribute based encryption for mobile cloud data storage. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 129, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Xiong, N.N.; Wang, J. Blocked linear secret sharing scheme for scalable attribute based encryption in manageable cloud storage system. Inf. Sci. 2018, 424, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mante, R.V.; Bajad, N.R. A Study of Searchable and Auditable Attribute Based Encryption in Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 10–12 June 2020; pp. 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; You, Z. An Efficient Attribute-Based Encryption Scheme With Policy Update and File Update in Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 6500–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, R.; Liu, L. Searchable encryption for healthcare clouds: A survey. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2017, 11, 978–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.X.; Wagner, D.; Perrig, A. Practical techniques for searches on encrypted data. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Berkeley, CA, USA, 14–17 May 2000; pp. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.J. Secure indexes. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2003, 2003, 216. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C.; Mitzenmacher, M. Privacy preserving keyword searches on remote encrypted data. In In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 442–455. [Google Scholar]

- Curtmola, R.; Garay, J.; Kamara, S.; Ostrovsky, R. Searchable symmetric encryption: Improved definitions and efficient constructions. J. Comput. Secur. 2011, 19, 895–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatidis, G.; Boldyreva, A.; O’Neill, A. Provably-secure schemes for basic query support in outsourced databases. In Proceedings of the IFIP Annual Conference on Data and Applications Security and Privacy, Redondo Beach, CA, USA, 8–11 July 2007; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Van Liesdonk, P.; Sedghi, S.; Doumen, J.; Hartel, P.; Jonker, W. Computationally efficient searchable symmetric encryption. In In Proceedings of the Workshop on Secure Data Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa, K.; Ohtaki, Y. UC-secure searchable symmetric encryption. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Kralendijk, Bonaire, The Netherlands, 27 February–2 March 2012; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, S.; Papamanthou, C.; Roeder, T. Dynamic searchable symmetric encryption. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and communications Security, Raleigh, NC, USA, 16–18 October 2012; pp. 965–976. [Google Scholar]

- Golle, P.; Staddon, J.; Waters, B. Secure conjunctive keyword search over encrypted data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security, Yellow Mountain, China, 8–11 June 2004; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, L.; Kamara, S.; Monrose, F. Achieving efficient conjunctive keyword searches over encrypted data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communications Security, Beijing, China, 10–14 December 2005; pp. 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Pieprzyk, J. Keyword field-free conjunctive keyword searches on encrypted data and extension for dynamic groups. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptology and Network Security, Hong Kong, China, 2–4 December 2008; pp. 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D.; Jarecki, S.; Jutla, C.; Krawczyk, H.; Roşu, M.C.; Steiner, M. Highly-scalable searchable symmetric encryption with support for boolean queries. In Proceedings of the Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 18–22 August 2013; pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, S.; Jarecki, S.; Krawczyk, H.; Nguyen, Q.; Rosu, M.; Steiner, M. Rich queries on encrypted data: Beyond exact matches. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Vienna, Austria, 21–25 September 2015; pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.A.; Kim, B.H.; Lee, D.H.; Chung, Y.D.; Zhan, J. Secure similarity search. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Granular Computing (GRC 2007), Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 2–4 November 2007; p. 598. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, E.; Shi, E.; Waters, B. Predicate privacy in encryption systems. In Proceedings of the Theory of Cryptography Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–17 March 2009; pp. 457–473. [Google Scholar]

- Bösch, C.; Tang, Q.; Hartel, P.; Jonker, W. Selective document retrieval from encrypted database. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security, Passau, Germany, 19–21 September 2012; pp. 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Cao, N.; Ren, K.; Lou, W. Fuzzy keyword search over encrypted data in cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2010 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–19 March 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, X. Efficient multi-user keyword search over encrypted data in cloud computing. Comput. Inform. 2013, 32, 723–738. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Yu, S.; Lou, W.; Hou, Y.T. Privacy-preserving multi-keyword fuzzy search over encrypted data in the cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2014-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Toronto, ON, Canada, 27 April–2 May 2014; pp. 2112–2120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Cao, N.; Li, J.; Ren, K.; Lou, W. Secure ranked keyword search over encrypted cloud data. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 30th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, Genova, Italy, 21–25 June 2010; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar]