Geological and Social Factors Related to Disasters Caused by Complex Mass Movements: The Quilloturo Landslide in Ecuador (2024)

Abstract

1. Introduction

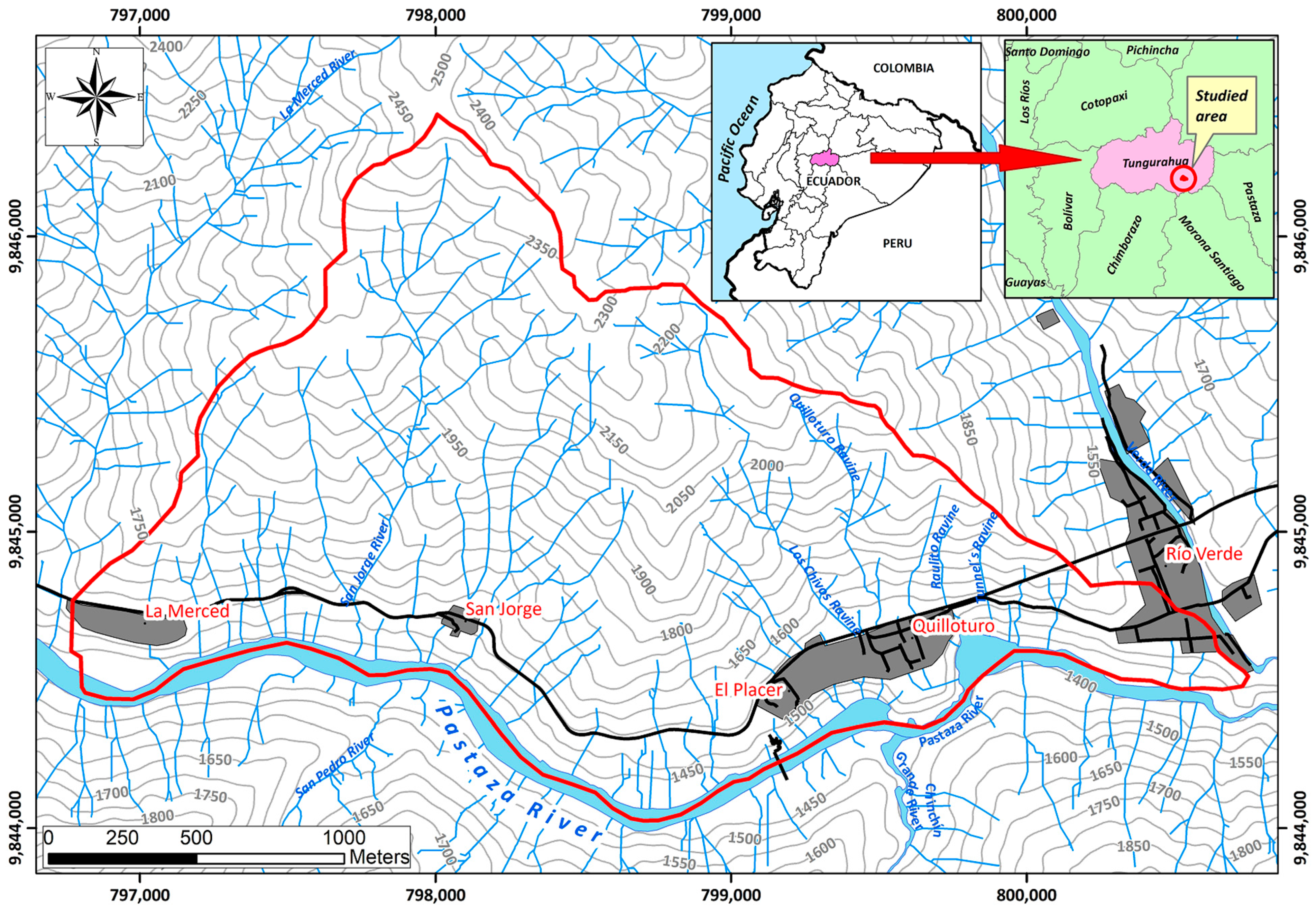

2. Geographical Location and Geological Characteristics

2.1. Geographical Location and Geomorphology

2.2. Geological Knowledge

3. Past and Background of Mass Movements in the Area

4. Methodology and Field Data Acquisition

4.1. Geological Field Data Acquisition Methodology

4.2. Social Knowledge and Methodology in the Analysis of Mass Movements

- a.

- Temporal and spatial characterization of the hamlets. Composed of an analysis of the history and development of the communities, economic activities, migration processes, and population growth, and finally, the identification of milestones that modified the social and territorial dynamics.

- b.

- Characterization of mass movements. This involved analyzing the location and names of drainage systems (ravines) according to local memory, describing land uses on hillsides (agriculture, grazing), and the relationship between the intensity and duration of rainfall and the occurrence of events.

- c.

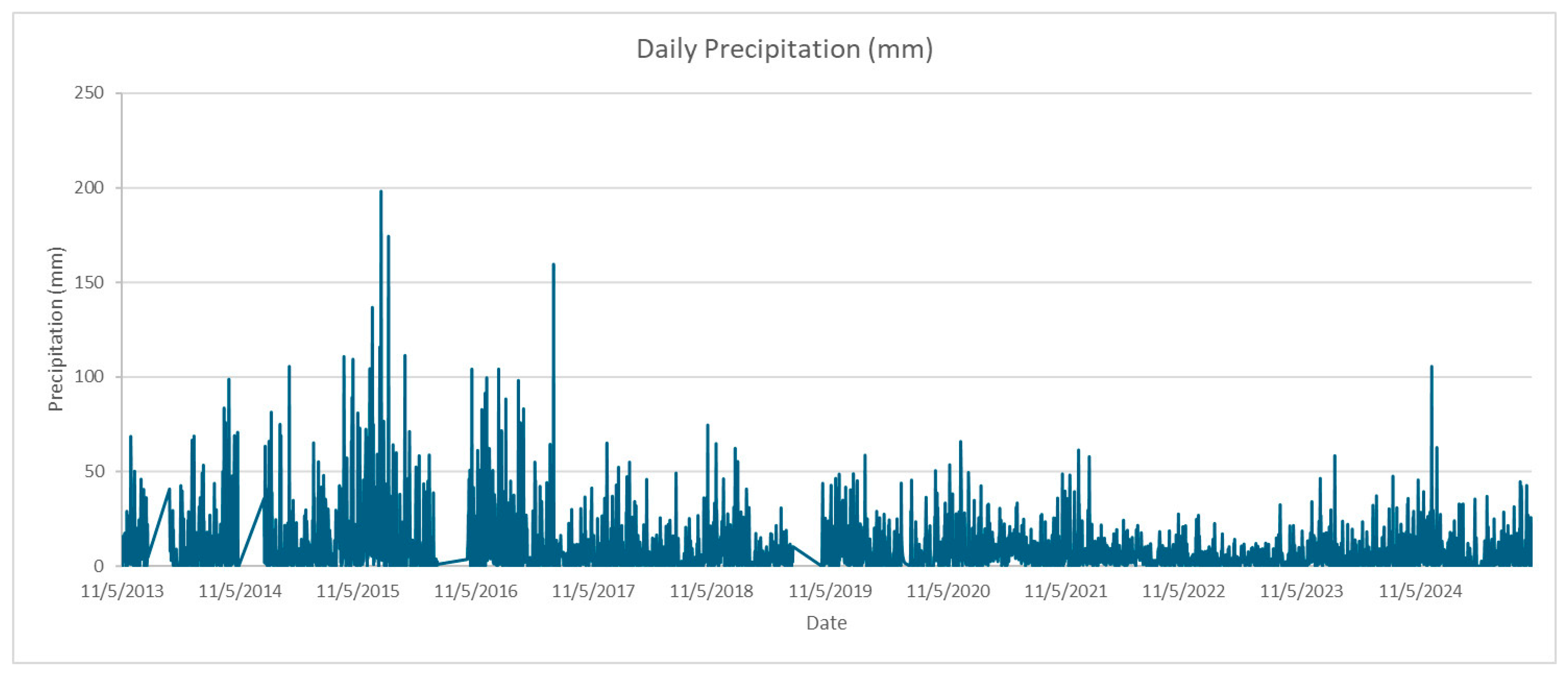

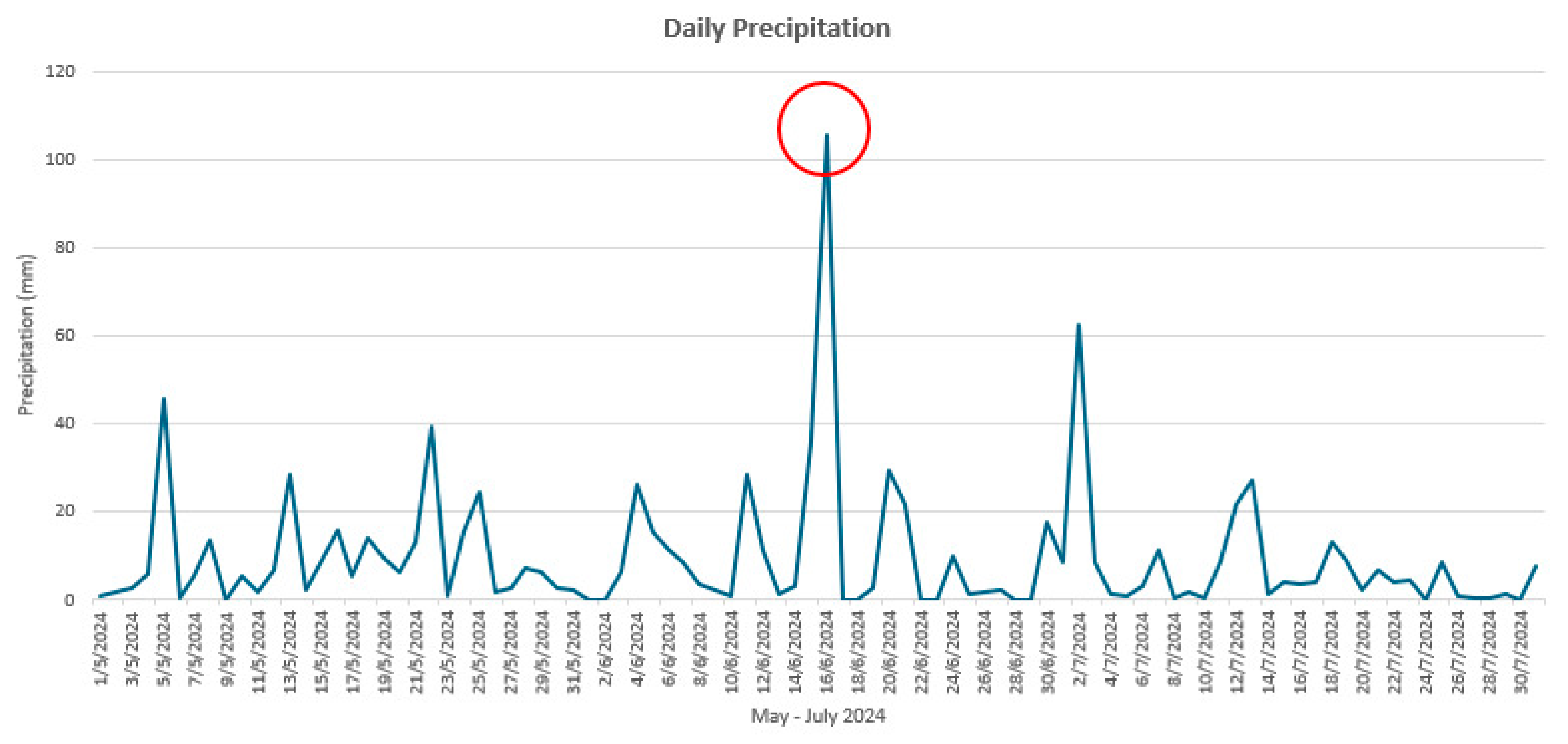

- Analysis of precipitation and the event of 16 June 2024. This included comparing recorded rainfall with previous years, identifying and describing the mass movements documented by the community, and recognizing natural “premonitory” factors observed by the inhabitants.

- d.

- Reconstruction of the sequence of events of June 2024. Based on the accounts of the chronology of the events, the reported impacts, and the assessment of the perceived magnitude.

- Identifying the characteristics of the hillsides, ravines, and springs through the creation of interactive maps;

- Describing mass movement events, their relationship to rainfall, and their impacts at the community level;

- Documenting historical aspects of the communities, their livelihoods, and social and economic transformations.

- Group creation and development of interactive maps (Figure 8), where geographical features, ravines, and past events were located;

- Plenary session for comparison and validation, which allowed for the exchange of information between groups and the prioritization of events and rainfall using a subjective scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents a minor event and five a major event, such as the one that occurred on 16 June 2024.;

- Collective construction of a timeline to identify relevant milestones from the formation of the hamlet to the 2024 event.

- First campaign: unstructured interviews with two eyewitnesses (Darwin Recalde and Carlos Freire) of the events of 15 and 16 June 2024, complemented by visits to the impact zone in Quilloturo. This activity enabled the reconstruction of the temporal and spatial sequence of rainfall and landslides, as well as their primary impacts.

- Second campaign: semi-structured interviews and the creation of community maps with three residents of El Placer and three of La Merced, focusing on local history, the affected areas, risk perception, and community strategies in response to the events.

5. Results

5.1. Local Geology and Implications for Mass Movements

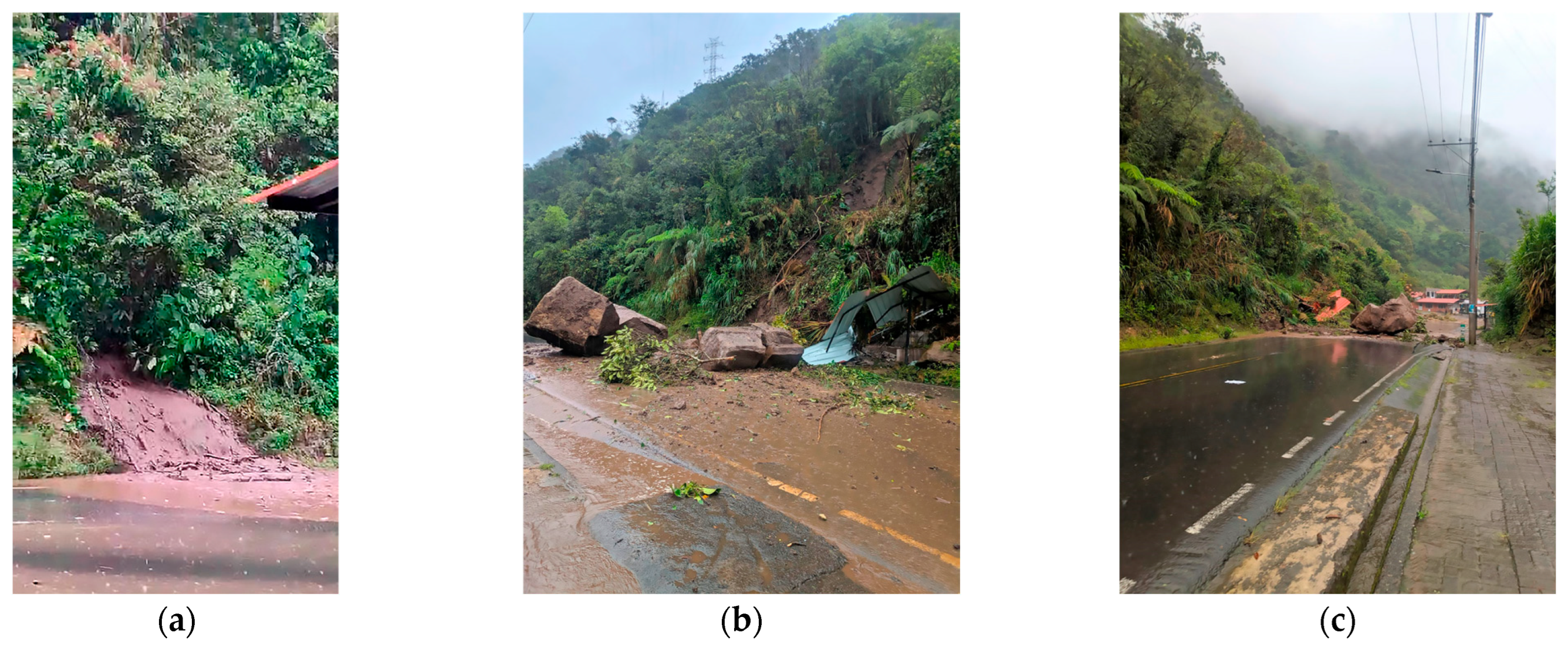

5.2. Field Verification and Inventory of Mass Movements

5.3. Field Distribution of Fallen Boulders and Typology

5.4. Complex Landslides Characterization

5.5. Social Perception of the Landslide Process

5.5.1. Community Perception and Classification of Historical Mass Movements and Associated Precipitation

- Level 1: very light rainfall, no flows related to it.

- Level 2: light rainfall, related to the 2018 flow. According to the Río Verde meteorological station, 74.6 mm of precipitation was recorded on 28 April 2018 (the day of the event).

- Level 3: moderate rainfall linked to the Los Chivos ravine event (2022), of shorter duration and lower intensity, with peaks between 08:00–11:00 and 13:00–14:00. According to data from the Río Verde meteorological station, 5.3 mm of precipitation was recorded on 11 August 2022 (the day of the event). It should be noted that the highest rainfall total related to that event, 14.2 mm, was recorded on 9 August 2022. Therefore, the event can be considered a result of accumulated rainfall.

- Level 4: normal winter rainfall, prolonged from night until midday, typical of June, July, and August.

- Level 5: heavy rain, similar or associated with the Quilloturo event (2024), beginning on 15 June around 8:00 p.m. and reaching maximum intensity between 2:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m. the following day. The Río Verde weather station recorded 35.7 mm of precipitation on 15 June 2024, and 105.6 mm on 16 June 2024 (the day of the event).

5.5.2. Community-Based Early Warning Indicators for Mass Movements

- Sudden drying of the ravine: in the Los Chivos ravine mudslide (2022), the flow stopped a day before the event, and in the Quilloturo ravine mudslide (2024), the water stopped flowing a few minutes before the mudslide occurred.

- Increased sediment content: the water flows down like a stream, with a greater amount of mud and fine materials.

- Increased stream flow: visibly larger or more turbulent flow.

- Noises or roars in the headwaters: unusual sounds, such as thunder or rockfalls, recorded days or hours before the event; for example, in Los Chivos (2022), roars were heard a week prior, and in Quilloturo (2024) for several minutes before the mudslide.

- Sound of rocks rolling within the stream.

- Persistent rain: moderate-intensity rainfall (levels 2 to 3, according to the local scale) lasting for more than an hour.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Summary of Institutional Technical Reports on the Quilloturo Landslide, 2024

Appendix B

Origin, Development, and Livelihoods of the Communities of La Merced, El Placer, and Quilloturo

Appendix C

Reconstruction of the Events of 15 and 16 June 2024, Based on Eyewitness Accounts

“Darwin’s sister warns him to be careful because material is flowing down the ravine in front of El Placer. Darwin tells her he is calm because he can see that material is flowing down. However, he warns his sister to be careful because the mud-water flow in the Quilloturo ravine has stopped” (instructions and comments from a resident).

“Several people who were standing on a corner looking toward the mountain, when the explosion hit, ran toward Quilloturo Street (where the projectiles landed), thinking the material was heading more toward El Placer” (comments from a resident).

References

- Petley, D. Global Patterns of Loss of Life from Landslides. Geology 2012, 40, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, T.; Crozier, M.J. The Nature of Landslide Hazard Impact. In Landslide Hazard and Risk; Glade, T., Anderson, M., Crozier, M.J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 41–74. ISBN 978-0-471-48663-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cruden, D.M.; Varnes, D.J. Landslide Types and Processes. In Landslides: Investigation and Mitigation; Turner, A.K., Shuster, R.L., Eds.; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 247, pp. 36–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hungr, O.; Leroueil, S.; Picarelli, L. The Varnes Classification of Landslide Types, an Update. Landslides 2014, 11, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highland, L.; Bobrowsky, P. The Landslide Handbook—A Guide to Understanding Landslides; Circular; Version 1.0; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns, R.L.; Valderrama, P.; Fauqué, L.; Penna, I.M.; Sepúlveda, S.; Moreiras, S.; Zavala Carrión, B. Landslides in the Andes and the Need to Communicate on an Interandean Level on Landslide Mapping and Research. Rev. Asoc. Geol. Argent. 2012, 69, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, C.P. The 1993 Landslide Dam at La Josefina in Southern Ecuador: A Review of “Sin Plazo Para La Esperanza”. Eng. Geol. 2004, 74, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Delgado, H.; Petley, D.N.; Bermúdez, M.A.; Sepúlveda, S.A. Fatal Landslides in Colombia (from Historical Times to 2020) and Their Socio-Economic Impacts. Landslides 2022, 19, 1689–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilatasig, L.; Torrijo, F.J.; Ibadango, E.; Troncoso, L.; Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Mateus, A.; Solano, S.; Viteri, F.; Alulema, R. Casual-Nuevo Alausí Landslide (Ecuador, March 2023): A Case Study on the Influence of the Anthropogenic Factors. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavell, A. Riesgo, desastre y territorio. La necesidad de los enfoques regionales/transnacionales. In Anuario Social y Político de América Latina y el Caribe; Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences: San José, Costa Rica, 2002; Volume 5, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Aristizábal, E.; Martínez, H.; Vélez, J.I. Una Revisión Sobre El Estudio de Movimientos En Masa Detonados Por Lluvias. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Ex. Fis. Nat. 2023, 34, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjekstad, O.; Highland, L. Economic and Social Impacts of Landslides. In Landslides—Disaster Risk Reduction; Sassa, K., Canuti, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 573–587. ISBN 978-3-540-69966-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Díaz, J.; Martínez-Labrín, S. Gestión Comunitaria Del Riesgo de Desastre: Una Propuesta Metodológica-Reflexiva Desde Las Metodologías Participativas. REDER 2021, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas Toral, R. Análisis de Susceptibilidad a Deslizamientos Aplicado a Grupos Socioeconómicos Vulnerables, Mediante Máxima Entropía (MaxEnt), En Las Parroquias: Cuenca, Nulti, Paccha, El Valle y Turi, Del Cantón Cuenca. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Loor Salazar, V.E.; Paucar Camacho, J.A.; Bravo Rosillo, N.G. Percepción del riesgo de la población ante amenazas de sismo, inundación y deslizamiento del cantón Portoviejo. Rev. San Gregor. 2022, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, L.; Lavell, A.; Pérez Ortega, G. La Gestión Del Riesgo de Desastres: Un Enfoque Basado En Procesos; Comunidad Andina, Secretaría General Editions: Quito, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zevallos Moreno, O. Las amenazas hidrometeorológicas en Quito. In Gestión de Riesgos en Quito; Carrión, A., Rebotier, J., Metzger, P., Puente Sotomayor, F., Eds.; IRD Éditions, Flacso Ecuador: Marseille, France, 2024; pp. 70–91. ISBN 978-2-7099-3051-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Lin, G.; Peng, B. Deciphering the Social Vulnerability of Landslides Using the Coefficient of Variation-Kullback-Leibler-TOPSIS at an Administrative Village Scale. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnes, D.J. Slope Movement Types and Processes. In Landslides—Analysis and Control: National Research Council, Washington, D.C.; Special Report; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; Volume 176, pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, A.; Rebotier, J.; Metzger, P.; Puente-Sotomayor, F. Gestión de Riesgos En Quito. Balance y Perspectivas de Treinta Años de Estudios, 1st ed.; FLACSO Quito, Ecuador/IRD: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; ISBN 978-9978-67-690-5. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ercole, R.; Trujillo, M. Amenazas, Vulnerabilidad, Capacidades y Riesgos En El Ecuador. Los Desastres, Un Reto Para El Desarrollo; COOPI, IRD y Oxfam: Quito, Ecuador, 2003; ISBN 9978-42-972-7. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, S.M.; Dias, M.C.D.A.; Alvalá, R.C.D.S.; Stenner, C.; Franco, C.; Ribeiro, J.V.M.; Souza, P.A.D.; Santana, R.A.S.D.M. População Urbana Exposta Aos Riscos de Deslizamentos, Inundações e Enxurradas No Brasil. Soc. Nat. 2019, 31, e46320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilatasig, L.; Ibadango, E.; Troncoso, L.; Mateus, A.; Alulema, R.; Alonso Pandavenes, O. Evaluación del Deslizamiento Casual Nuevo Alausí y su Zona de Influencia; FIGEMPA—Universidad Central del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Carrera, A.C.; Mendoza, M.E.; Allende, T.C.; Macías, J.L. A Review of Recent Studies on Landslide Hazard in Latin America. Phys. Geogr. 2023, 44, 243–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, L.; Pilatasig, L.; Ibadango, E.; Mateus, A.; Bermeo, A. Evaluación de Susceptibilidad a Movimientos En Masa de Las Laderas y Taludes Relacionados Con El Sector de La Merced Hasta Quilloturo, y Su Zona de Influencia; Quito, Ecuador, 2024; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería Geoportal SigTierra-MAG. Sistema Nacional de Información de Tierras Rurales e Infraestructura Tecnológica 2010. Available online: http://www.sigtierras.gob.ec/centro-geomatico-virtual/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Litherland, M.; Aspden, J.A.; Jemielita, R. The Metamorphic Belts of Ecuador; Overseas Memoir, 1a; British Geological Survey: Nottingham, UK, 1994; Volume 11, ISBN 0-85272-239-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, J.; Vergely, P. Tectónica, 1st ed.; Edición en español; Limusa: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, L. El Podcast Como Estrategia Para Difundir El Conocimiento Comunitario Sobre Peligros Volcánicos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GADP RioVerde. Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial 2019–2023; Gad Parroquial de Rio Verde: Baños de Tungurahua, Ecuador, 2018; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Gestión de Riesgos. Informe de Situación—Época Lluviosa, Ecuador; Secretaría de Gestión de Riesgos: Quito, Ecuador, 2018; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- El Telégrafo editorial La Carretera Baños-Puyo Se Abrió Tras 24 Horas Sin Lluvias. El Telegrafo, 25 December 2018.

- EcoAmazónico Tristeza y Desconsuelo Por La Muerte de 3 Personas En El Placer. EcoAmazónico Comunica y une Voces 2022.

- LaHusen, S.R.; Grant, A.R.R. Complex Landslide Patterns Explained by Local Intra-Unit Variability of Stratigraphy and Structure: Case Study in the Tyee Formation, Oregon, USA. Eng. Geol. 2024, 329, 107387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, W.; Locher, T.; Núñez, I. Mechanics of Deep Seated Mass Movements in Metamorphic Rocks of the Ecuadorian Andes. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium On Landslides, Lausanne, Switzerland, 10–15 July 1988; A.A. Balkema, Brookfield, Rotterdam: Laussane, Switzerland, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Correa Campués, C.J. Análisis de La Susceptibilidad de Los Fenómenos de Remoción En Masa de La Carretera Loja-Zamora. Master’s Thesis, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; An, B.-W. Social Vulnerability Assessment of Landslide Disaster Based on Improved TOPSIS Method: Case Study of Eleven Small Towns in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, O.D. The Need for Rethinking the Concepts of Vulnerability and Risk from a Holistic Perspective: A Necessary Review and Criticism for Effective Risk Management. In Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; p. 256. ISBN 978-1-84977-192-4. [Google Scholar]

- Van Westen, C.J.; Castellanos, E.; Kuriakose, S.L. Spatial Data for Landslide Susceptibility, Hazard, and Vulnerability Assessment: An Overview. Eng. Geol. 2008, 102, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Acosta, V. El riesgo como construcción social y la construcción social de riesgos. Desacatos 2005, 19, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Cortes, N.L.; Ayala Macías, E. Resistir en el paisaje: Voces y gestión de la comunidad ante los deslizamientos e inundaciones en la colonia Sánchez Taboada de Tijuana. Decumanus 2025, 15, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga Armjo, S. La memoria y resiliencia de habitantes de la comuna de Hualqui frente a desbordes del río Biobío. Urbearq 2023, 17, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, L.; Torrijo, F.J.; Ibadango, E.; Pilatasig, L.; Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Mateus, A.; Solano, S.; Cañar, R.; Rondal, N.; Viteri, F. Analysis of the Impact Area of the 2022 El Tejado Ravine Mudflow (Quito, Ecuador) from the Sedimentological and the Published Multimedia Documents Approach. GeoHazards 2024, 5, 596–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, S.S.; Petley, D.N. Regional trends and controlling factors of fatal landslides in Latin America and the Caribbean. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. ¿Cómo superar los retos de la vivienda rural en América Latina y el Caribe? Ciudad. Sosten. 2021. Available online: https://www.iadb.org/es/blog/desarrollo-urbano-y-vivienda/como-superar-los-retos-de-la-vivienda-rural-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos. SitRep N.01-Lluvias, 16 de Junio de 2024. Informe De Situación Cantonal Baños De Agua Santa; Monitoreo de Eventos Adversos; Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos. Informe de Análisis de Los Factores de Riesgo Presentes En Los Sectores El Placer y Quilloturo; Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos. SitRep N.32-Lluvias, 16 de Junio de 2024. Informe De Situación Cantonal Baños De Agua Santa; Monitoreo de Eventos Adversos; Secretaría Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- IIGE Informe de Asistencia Técnica de Emergencia Para El Levantamiento de Información Geológica, Fotogramétrica e Identificación de Movimientos En Masa En El Cantón Baños de Agua Santa, Provincia de Tungurahua; IIGE Instituto de Investigación Geológico y Energético: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; p. 26.

| Code | Type of Slide | Area (m2) | Direction (1) | Inclination (°) | State of Activity | Height (m) | Length (m) | Wide (m) | Thickness (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI-77 | Debris flow | 18,816.6 | 150 | 12 | Pendent | 150.0 | 100.0 | 1.0 | |

| EI-17 | Debris flow | 98,676.2 | 165 | 12 | Pendent | 150.0 | 250.0 | 3.0 | |

| LP-65 | Debris flow | 5931.7 | 175 | Active | |||||

| LP-12 | Rotational | 2387.7 | 175 | Active | 2.0 | ||||

| EI-24 | Debris flow | 9153.8 | 180 | 50 | Pendent | 100.0 | 20.0 | ||

| LP-60 | Mud flow | 6578.9 | 145 | Active | 35.0 | 15.0 | |||

| EI-31 | Rock and debris flow | 1620.4 | 250 | 35 | Pendent | 100.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-30 | Rotational | 79,174.3 | 210 | 28 | Pendent | 50.0 | 1000.0 | 400.0 | |

| EI-34 | Earth and debris flow | 1333.1 | 170 | 45 | Active | 10.0 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 |

| EI-39 | Debris flow | 1861.5 | 190 | 27 | Pendent | 100.0 | 50.0 | ||

| EI-41 | Translational | 2621.0 | 180 | 35 | Pendent | 50.0 | 30.0 | ||

| EI-37 | Earth and debris flow | 198.9 | 180 | 40 | Active | 3.0 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 3.0 |

| EI-36 | Earth and debris flow | 480.0 | 215 | 50 | Active | 1.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 | 10.0 |

| EI-26 | Earth and debris flow | 24,710.4 | 170 | 47 | Pendent | 50.0 | 40.0 | ||

| LP-13A | Avalanche | 620.2 | 235 | 35 | Active | 4.0 | 5.0 | ||

| EI-21 | Earth and debris flow | 416.3 | 235 | 65 | Active | 40.0 | 5.0 | ||

| AM-44 | Rotational | 2156.2 | 190 | Inactive | 3.0 | 9.0 | 15.0 | ||

| AM-42 | Translational | 806.8 | 120 | Active | |||||

| EI-11 | Debris flow | 478.3 | 150 | 35 | Pendent | 100.0 | 8.0 | ||

| AM-41 | Translational | 2741.1 | 150 | Active | |||||

| EI-18 | Earth and debris flow | 9345.7 | 343 | 47 | Pendent | 150.0 | 25.0 | ||

| EI-50 | Earth and debris flow | 3395.0 | 70 | 60 | Pendent | 15.0 | 25.0 | ||

| EI-10 | Earth and debris flow | 1452.6 | 130 | 28 | Active | 50.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-20 | Earth and debris flow | 99.3 | 180 | 35 | Pendent | 3.0 | 15.0 | 5.0 | |

| EI-01 | Earth and debris flow | 625.4 | 285 | 48 | Active | 5.0 | 5.0 | ||

| LP-01 | Avalanche | 53.9 | 225 | Active | 1.0 | 8.0 | |||

| EI-54 | Debris flow | 123.1 | 165 | 18 | Pendent | 100.0 | 5.0 | ||

| EI-53 | Earth and debris flow | 8116.6 | 192 | 35 | Pendent | 50.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-23 | Debris flow | 365.6 | 220 | 30 | Pendent | 30.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-43 | Earth and debris flow | 1654.1 | 188 | 74 | Active | 200.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-45 | Debris flow | 17,565.6 | 280 | 35 | Pendent | 200.0 | 20.0 | ||

| EI-09 | Old landslide | 2291.0 | 135 | 28 | Inactive | 100.0 | 50.0 | ||

| EI-62 | Translational | 9950.9 | 130 | 35 | Pendent | 3.0 | 500.0 | 200.0 | |

| LP-60A | Translational | 3827.2 | 170 | Active | 16.0 | 25.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Troncoso, L.; Echarri, F.J.T.; Pilatasig, L.; Ibadango, E.; Mateus, A.; Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Bermeo, A.; Robayo, F.J.; Jost, L. Geological and Social Factors Related to Disasters Caused by Complex Mass Movements: The Quilloturo Landslide in Ecuador (2024). GeoHazards 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010004

Troncoso L, Echarri FJT, Pilatasig L, Ibadango E, Mateus A, Alonso-Pandavenes O, Bermeo A, Robayo FJ, Jost L. Geological and Social Factors Related to Disasters Caused by Complex Mass Movements: The Quilloturo Landslide in Ecuador (2024). GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleTroncoso, Liliana, Francisco Javier Torrijo Echarri, Luis Pilatasig, Elías Ibadango, Alex Mateus, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Adans Bermeo, Francisco Javier Robayo, and Louis Jost. 2026. "Geological and Social Factors Related to Disasters Caused by Complex Mass Movements: The Quilloturo Landslide in Ecuador (2024)" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010004

APA StyleTroncoso, L., Echarri, F. J. T., Pilatasig, L., Ibadango, E., Mateus, A., Alonso-Pandavenes, O., Bermeo, A., Robayo, F. J., & Jost, L. (2026). Geological and Social Factors Related to Disasters Caused by Complex Mass Movements: The Quilloturo Landslide in Ecuador (2024). GeoHazards, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010004