Basement-Controlled Urban Fracturing: Evidence from Las Pilas, Zacatecas, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

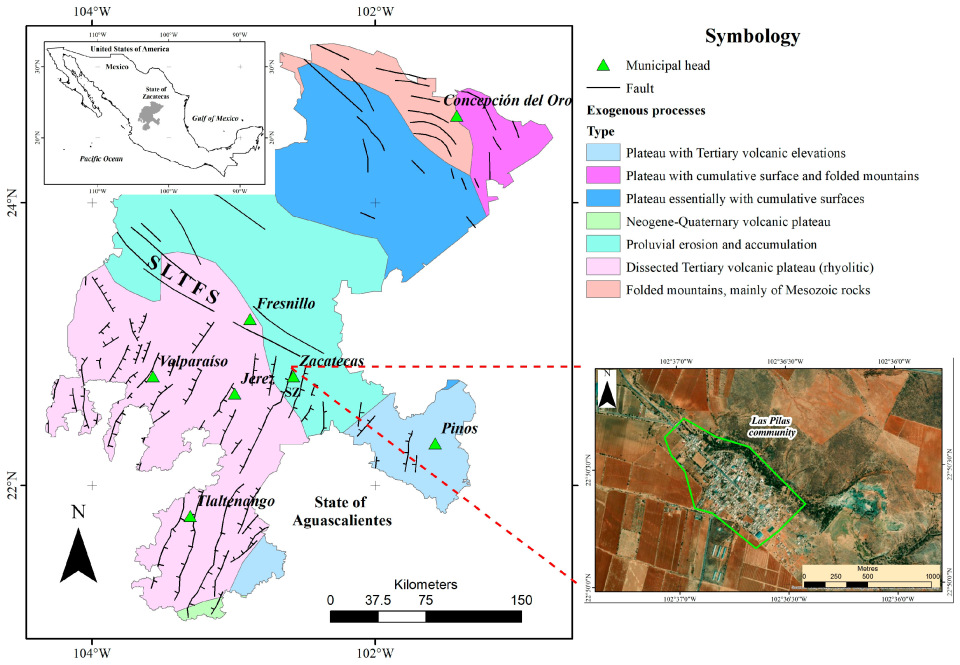

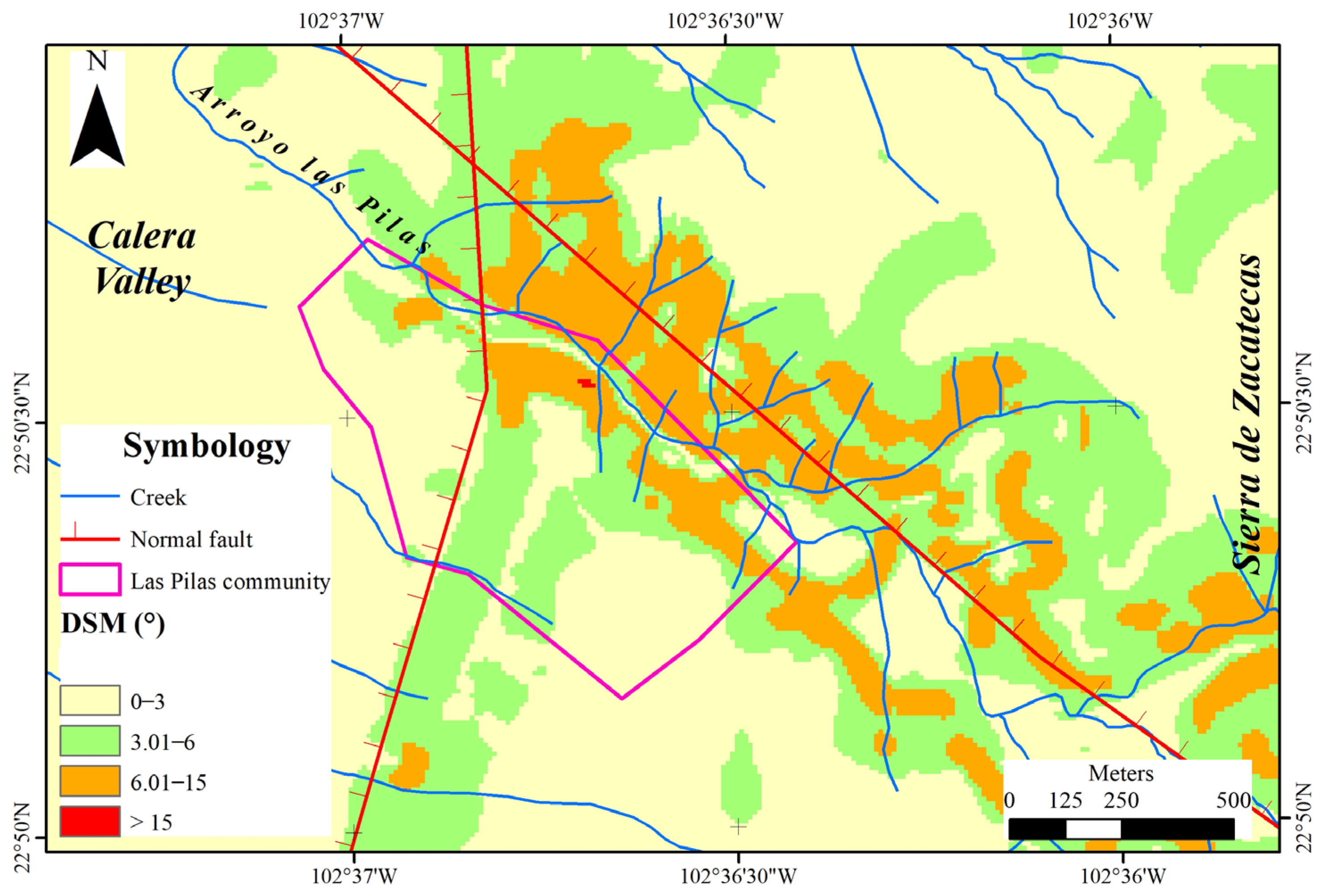

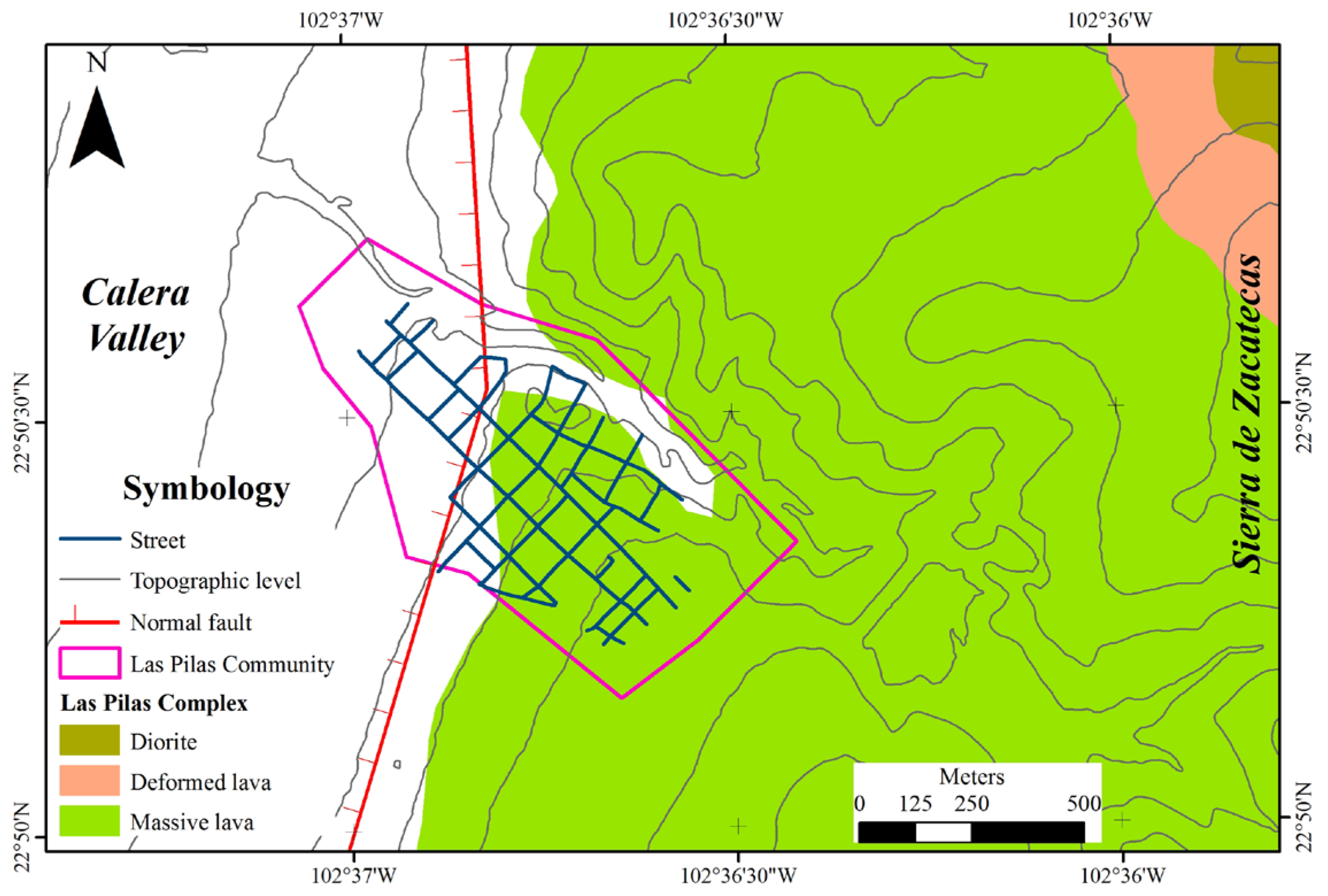

2. Geologic Framework

3. Materials and Methods

- -

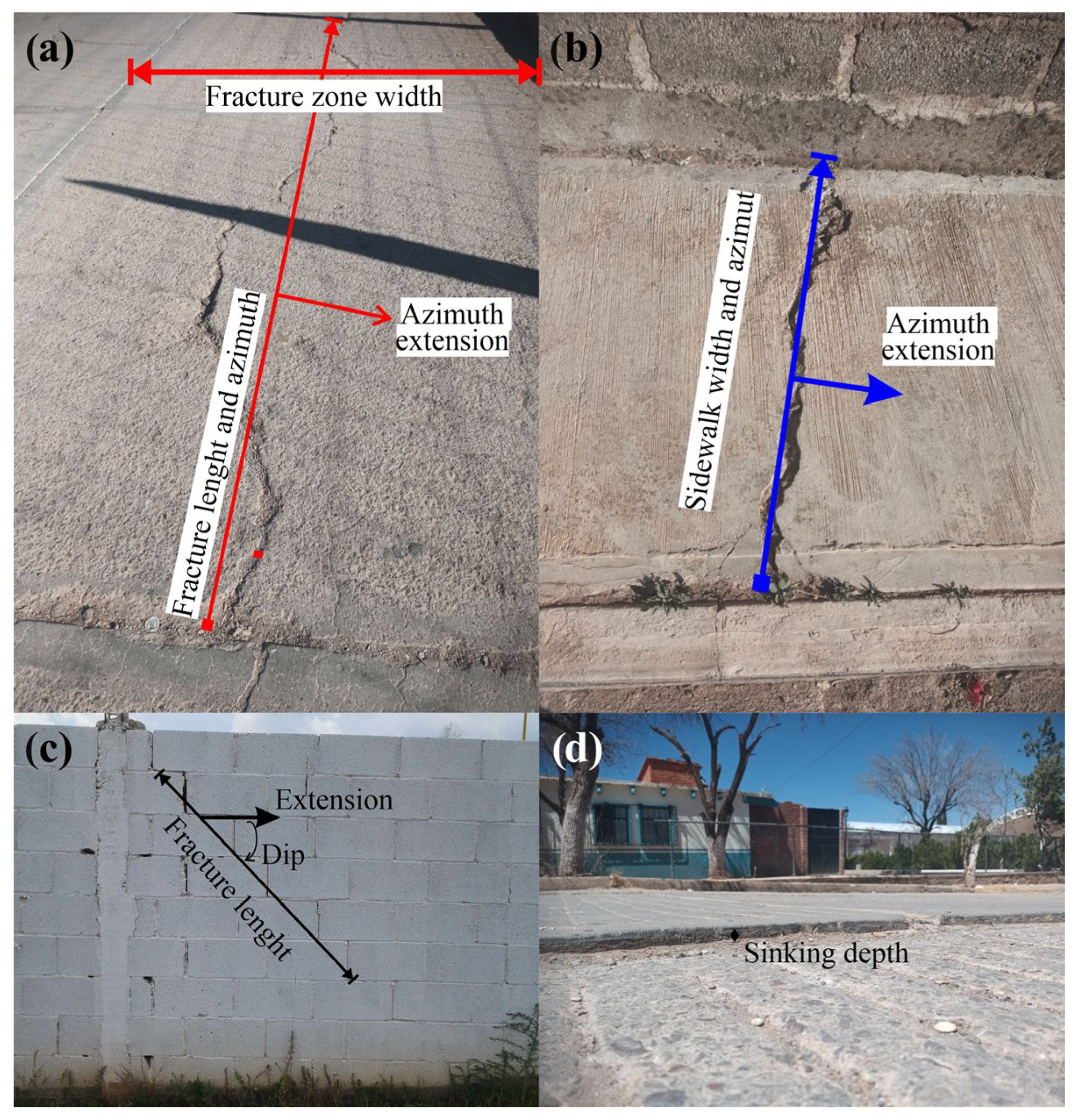

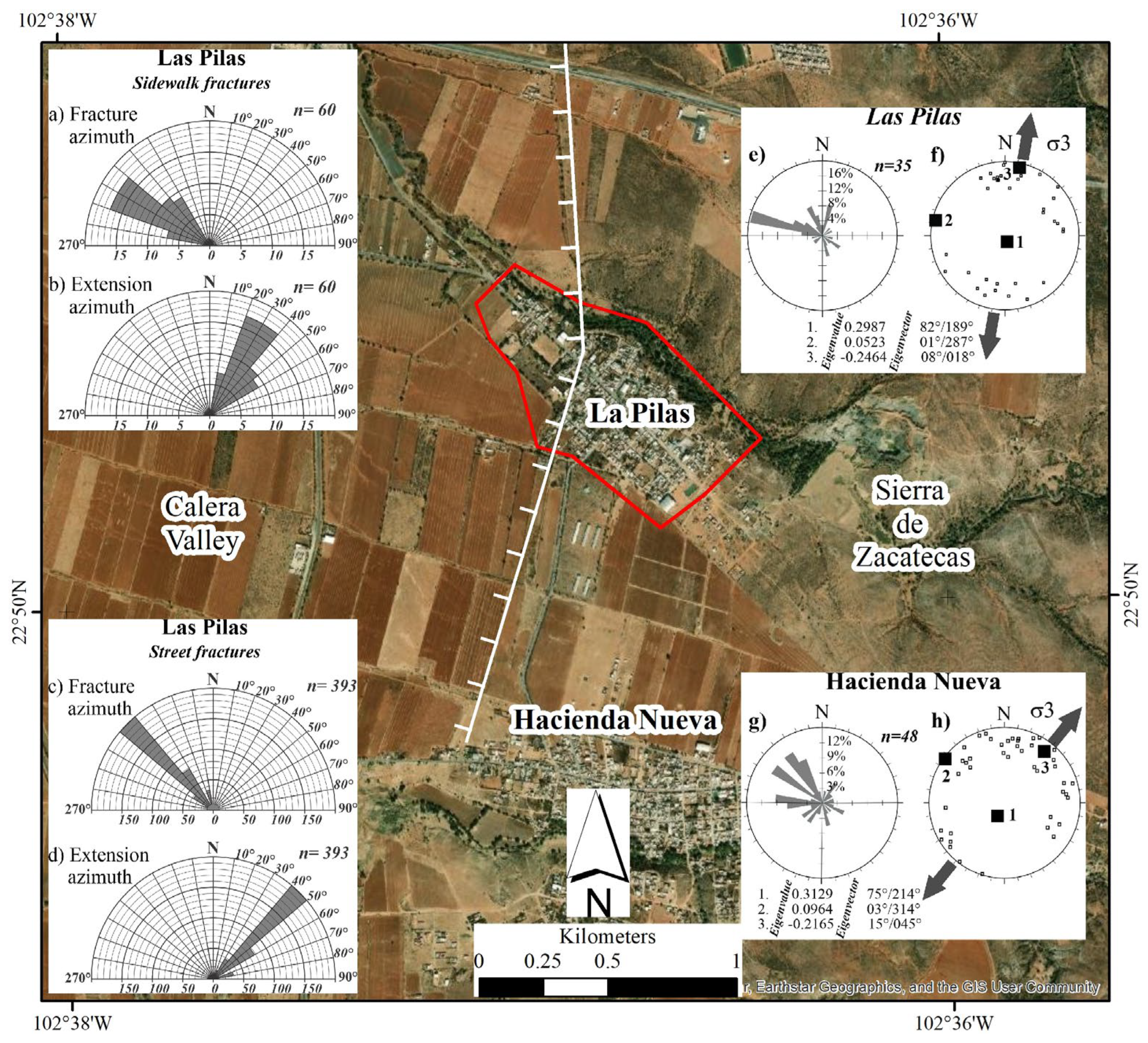

- Street fractures (Figure 4a) are the predominant structural features. For fractures that deviate from a straight line, the azimuth is determined from the feature’s start point to its endpoint, which defines the fracture’s minimum length. The extension azimuth is perpendicular to the fracture’s strike, oriented toward the side exhibiting downward displacement or, in the absence of visible displacement, toward the downslope direction. The fracture zone width corresponds to the affected area within the street, such as the concrete slab or asphalt paving. The fracture aperture (width) is recorded as the maximum open dimension of the break. The fracture was georeferenced by its starting point according to the walking direction.

- -

- Sidewalk fractures (Figure 4b) share similar measurement parameters with street fractures; however, the sidewalk’s width is a uniform 1 m across the entire community. They were georeferenced in the same manner as the street ones.

- -

- For Wall fractures (Figure 4c), the house front width is noted at the location of the most significant fracture, along with the fracture’s maximum thickness. If the fracture trace is irregular, the endpoints are used to determine its length and dip, with the extension azimuth being equated to the dip direction. In the case of vertical fracture, the extension azimuth is aligned with the walking survey path. This kind of fracture was georeferenced using the middle point of the wall where it is located.

- -

- The final category assessed was the subsidence of sidewalks and street blocks (Figure 4d), for which only the magnitude of vertical displacement (depth) was measured. The georeferencing point is the one with the maximum displacement.

- -

- Relief energy is defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum elevations within each cell.

- -

- Dissection density is the sum of the length of all creeks within the cell [39].

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herrera-García, G.; Ezquerro, P.; Tomás, R.; Béjar-Pizarro, M.; López-Vinielles, J.; Rossi, M.; Mateos, R.M.; Carreón-Freyre, D.; Lambert, J.; Teatini, P.; et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 2021, 371, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbey, T.J. The influence of faults in basin-fill deposits on land subsidence, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Yurrita, P.J. Land subsidence and environmental law in Mexico: A reflection on civil liability for environmental damage. In Land Subsidence, Associated Hazards and the Role of Natural Resources Development; IAHS Red Book 339; IAHS: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, D.L.; Burbey, T.J. Review: Regional land subsidence accompanying groundwater extraction. Hydrogeol. J. 2011, 19, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Marín, M.; Pacheco-Martínez, J.; Burbey, T.J.; Carreón-Freyre, D.C.; Ochoa-González, G.H.; Campos-Moreno, G.E.; de Lira-Gómez, P. Evaluation of subsurface infiltration and displacement in a subsidence-reactivated normal fault in the Aguascalientes Valley, Mexico. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Miranda, S.; Tuxpan-Vargas, J.; Ramos-Leal, J.A.; Hernández-Madrigal, V.A.; Villaseñor-Reyes, C.I. Land subsidence by groundwater over-exploitation from aquifers in tectonic valleys of Central Mexico: A review. Eng. Geol. 2018, 246, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreón-Freyre, D.; Cerca, M.; Gutiérrez-Calderón, R.; Alcántara-Durán, C.; Strozzi, T.; Teatini, P. Land subsidence and associated ground fracturing in urban areas. Study cases in Central Mexico. In Geotechnical Engineering in the XXI Century: Lessons Learned and Future Challenges; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1684–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Castellazzi, P.; Arroyo-Domínguez, N.; Martel, R.; Calderhead, A.I.; Normand, J.C.L.; Gárfias, J.; Rivera, A. Land subsidence in major cities of Central Mexico: Interpreting InSAR-derived land subsidence mapping with hydrogeologic data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2016, 47, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, F.; Tapete, D. Satellite InSAR survey of structurally-controlled land subsidence due to groundwater exploitation in the Aguascalientes Valley, Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 254, 112254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viets, V.F.; Vaugham, C.K.; Harding, R.C. Environmental and Economic Effect of Subsidence, 1st ed.; Contract W-7405-ENG-48; United Stated Department of Energy: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1979; p. 237.

- Kok, S.; Costa, A.L. Framework for economic cost assessment of land subsidence. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 1931–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Government of Aguascalientes. Sistema de Información de Fallas Geológicas y Grietas. Available online: https://www.aguascalientes.gob.mx/sop/sifagg/web/mapa.asp (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Arizona Geological Survey. Available online: https://azgs.arizona.edu/center-natural-hazards/earth-fissures-subsidence-karst-arizona (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Poland, J.F. Guidebook to Studies of Land Subsidence Due to Ground-Water Withdrawal; UNESCO Studies and Reports in Hydrogeology 40; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1984. Available online: http://wwwrcamnl.wr.usgs.gov/rgws/Unesco/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Galloway, D.; Jones, D.R.; Ingebritsen, S.E. Land Subsidence in the United States; United States Geological Survey Circular, 1182; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1999. Available online: http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/circ1182/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Galloway, D.L.; Bawden, G.W.; Leake, S.A.; Honegger, D.G. Land Subsidence Hazards. In Landslide and Land Subsidence Hazards to Pipelines; Open File Report 2008-1164; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Bluhm-Gutiérez, J.; Valle-Rodríguez, S.; Pineda-Martínez, L.F.; Huerta-García, J.; Núñez-Peña, E.P. Distribución del esfuerzo de extensión en la infraestructura urbana de la ciudad de Zacatecas y su relación con la morfología en la generación de zonas de riesgo. GEOS 2015, 35, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Pineda-Martínez, L.F.; Rodríguez-González, B.; Reveles-Flores, S.M.T.; Valle-Rodríguez, S.; Chávez-Guajardo, A.E.; Mandujano-García, C.D. La influencia de la deformación del basamento en el desarrollo de fracturas en la infraestructura urbana de la Zona Metropolitana de Zacatecas. GEOS 2023, 43, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-del Río, A.L. La Influencia de la Geomorfología en los Procesos de Erosión y sus Efectos en la Loma de las Bolsas, Zacatecas, Zacatecas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas, Mexico, 4 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muro-Ortega, J.A.; Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Bluhm-Gutiérrez, J.; Pineda-Martínez, L.F.; Rodríguez-González, B.; Valle-Rodríguez, S.; Reveles-Flores, S.M.T. Geological risk assessment by a fracture measurement procedure in an urban area of Zacatecas, Mexico. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pérez, R.G.; Terrones-Alfaro, I.V.; Pérez-Mota, M. Estudio del Fracturamiento en la Infraestructura Urbana y su Relación con los Procesos Geomórficos y el Basamento de la Parte SE de la Cabecera Municipal de Guadalupe, Zacatecas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas, Mexico, 1 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Hubp, J. El relieve de la República Mexicana. Inst. Geol. Rev. 1990, 9, 82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Peltier, L.C. The geographic cycle in periglacial regions as it is related to climatic geomorphology. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1950, 40, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fookes, P.G.; Dearman, W.R.; Franklin, J.A. Some engineering aspects of rock weathering with field examples from Dartmoor and elsewhere. Q. J. Eng. Geol. 1971, 4, 139–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Alaniz-Álvarez, S.A.; Camprubí í Cano, A. La Mesa Central de México: Estratigrafía, estructura y evolución tectónica cenozoica. Boletín Soc. Geol. Mex. 2005, 57, 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Del Pilar-Martínez, A.; Suárez-Arias, A.M.; Ángeles-Moreno, E.; Alaniz-Álvarez, S.A.; Levresse, G.; Xu, S.; Olmos-Moya, M.J.P.; Báez-López, J.A. Una revisión de la geología y evolución tectónica cenozoicas de la Mesa Central de México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Geol. 2023, 40, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza-Aguirre, I.; Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Alaniz-Álvarez, S.A.; Iriondo, A. Relaciones estratigráfico-estructurales en la intersección del sistema de fallas San Luis-Tepehuanes y el graben de Aguascalientes, México central. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Geol. 2008, 25, 533–548. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Gómez, J.J.; Henry, C.D.; Luhr, J.F. Evolución tectonomagmática post-paleocénica de la Sierra Madre Occidental y de la porción meridional de la provincia tectónica de Cuencas y Sierras, México. Boletín Soc. Geol. Mex. 2000, 53, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Martínez, J.J. Bosquejo Geológico del Distrito Minero de Zacatecas; Consejo de Recursos Naturales no Renovables Boletín 52; Consejo de Recursos Naturales no Renovables: Mexico City, Mexico, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, B.F.; Clark, K.F. The Zacatecas Mining District: A Tertiary caldera complex associated with precious and base metal mineralization. Econ. Geol. 1988, 83, 1668–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Suárez-Plascencia, C.; Pérez-Román, A.M.; Ortiz-Acevedo, O.; Bañuelos-Álvarez, C.A. La Secuencia Volcánica Terciaria del Cerro La Virgen y los procesos geomorfológicos que generan riesgo en la zona conurbada Zacatecas-Guadalupe. GEOS 2003, 23, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Delgado-Argote, L.A.; Weber, B.; Núñez-Peña, E.P.; Valencia, V.A.; Ortiz-Acevedo, O. Kinematics and U-Pb dating of detrital zircons from the Sierra de Zacatecas, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Geol. 2009, 26, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Solari, L.; García y Barragán, J.C.; Carrillo-Castillo, C.; Bluhm-Gutiérrez, J.; García-Sandoval, P.; Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Núñez-Peña, E.P. The Palaeocene-early Oligocene Zacatecas conglomerate, Mexico: Sedimentology, detrital zircon U-Pb ages, and sandstone provenance. Int. Geol. Rev. 2016, 58, 826–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Flores, B.; Solari, L.; Escalona-Alcázar, F.J. The Mesozoic successions of western Sierra de Zacatecas, central Mexico: Provenance and tectonic implications. Geol. Mag. 2016, 153, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-Díaz, E.; Lawton, T.F.; Juárez-Arriaga, E.; Chávez-Cabello, G. The Cretaceous-Paleogene Mexican Orogen: Structure, basin development, magmatism and tectonics. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 183, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de Información Topográfica F13B58 (Zacatecas) Escala 1:50 000 Serie III. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463832034 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano (SEDATU). Términos de Referencia Para la Elaboración de Altas de Peligros y/o Riesgos 2016. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/135433/TR_AR_231016_Pu_blico.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Escalona-Alcázar, F.J.; Escobedo-Arellano, B.; Castillo-Félix, B.; García-Sandoval, P.; Gurrola-Menchaca, L.L.; Carrillo-Castillo, C.; Núñez-Peña, E.P.; Bluhm-Gutiérrez, J.; Esparza-Martínez, A. A geologic and geomorphologic analysis of the Zacatecas and Guadalupe quadrangles in order to define hazardous zones associated with the erosion processes. In Sustainable Development: Authoritative and Leading Edge Content for Environmental Management; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Hubp, J. Elementos de Geomorfología Aplicada (Métodos Cartográficos); Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, J.P. Criteria for the sense of movement on fault surfaces in brittle rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 1987, 9, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, R.W.; Cardozo, N.; Fisher, D.M. Structural Geology Algorithms: Vectors and Tensors; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marret, R.; Allmendinger, R.W. Kinematic analysis of fault-slip data. J. Struct. Geol. 1990, 12, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (SEDESOL). Bases Para la Estandarización en la Elaboración de Atlas de Riesgos y Catálogo de Datos Geográficos Para Representar el Riesgo 2014. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/40838/Bases_AR_PRAH_2014.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Carreón-Freyre, D.C.; Cerca, M.; Hernández-Marín, M. Propagation of fracturing related to land subsidence in the Valley of Queretaro, México. In Land Subsidence; Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussard, E.; Wdowinski, S.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Amelung, F. Land subsidence in central Mexico detected by ALOS InSAR time-series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Martínez, P.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Wdowinski, S.; Hernández-Marín, M.; Ortiz-Lozano, J.A.; Zermeño-de León, M.E. Application of InSAR and gravimetry for land subsidence hazard zoning in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17035–17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Villavicencio, H.; Pacheco-Martínez, J.; Ochoa-González, G.H.; Hernández-Marín, M.; Hernández-Madrigal, V.H.; López-Doncel, R.A.; Reyes-Cedeño, I.G. Determination of susceptibility to the generation of discontinuities related to land subsidence using the frequency radio method in the City of Aguascalientes, Mexico. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF). Acuerdo por el Que se da a Conocer Los Resultados Del Estudio Técnico de las Aguas Nacionales Subterráneas Del Acuífero Calera, Clave 3225, en el Estado de Zacatecas, Región Hidrológico-Administrativa VII, Cuencas Centrales del Norte. Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/etj_web/docs_ETJ/ETJ_3225.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Comisión Nacional del Agua (CONAGUA). Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en el Acuífero Calera (3225), Estado de Zacatecas. Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/Edos_Acuiferos_18/zacatecas/DR_3225.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Oreano, D.B.; Barajas, L.D. Fallamiento en la cuenca de Calera en el Estado de Zacatecas, México. In Agua Subterránea: Manantial de Vida Para Aprovechar y Proteger, Proceedings of the XI Congreso Latinoamericano de Hidrogeología y IV Congreso Colombiano de Hidrogeología, Memoirs, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 20–24 August 2012; CONICET: Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Tristán-González, M.; Torres-Hernández, J.R.; Labarthe-Hernández, G.; Aguillón-Robles, A.; Yza-Guzmán, R. Control estructural para el emplazamiento de vetas y domos félsicos en el Distrito Minero de Zacatecas, México. Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex. 2012, 64, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, A.; Johannessen, M.U.; Ellingssen, T.S.S. Fault core thickness: Insight from silisiclastic and carbonate rocks. Geofluids 2019, 1, 2918673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure | Number of Data |

|---|---|

| Street fracture | 393 |

| Sidewalk fracture | 60 |

| Wall fracture | 5 |

| Sinking | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Escalona-Alcázar, F.d.J.; García-Paniagua, E.; Pineda-Martínez, L.F.; Rodríguez-González, B.; Reveles-Flores, S.M.T.; Valle-Rodríguez, S.; Mandujano-García, C.D. Basement-Controlled Urban Fracturing: Evidence from Las Pilas, Zacatecas, Mexico. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010006

Escalona-Alcázar FdJ, García-Paniagua E, Pineda-Martínez LF, Rodríguez-González B, Reveles-Flores SMT, Valle-Rodríguez S, Mandujano-García CD. Basement-Controlled Urban Fracturing: Evidence from Las Pilas, Zacatecas, Mexico. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscalona-Alcázar, Felipe de Jesús, Estefanía García-Paniagua, Luis Felipe Pineda-Martínez, Baudelio Rodríguez-González, Sayde María Teresa Reveles-Flores, Santiago Valle-Rodríguez, and Cruz Daniel Mandujano-García. 2026. "Basement-Controlled Urban Fracturing: Evidence from Las Pilas, Zacatecas, Mexico" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010006

APA StyleEscalona-Alcázar, F. d. J., García-Paniagua, E., Pineda-Martínez, L. F., Rodríguez-González, B., Reveles-Flores, S. M. T., Valle-Rodríguez, S., & Mandujano-García, C. D. (2026). Basement-Controlled Urban Fracturing: Evidence from Las Pilas, Zacatecas, Mexico. GeoHazards, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010006