Co-Seismic Landslide Detection Combining Multiple Classifiers Based on Weighted Voting: A Case Study of the Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in 2017

Abstract

1. Introduction

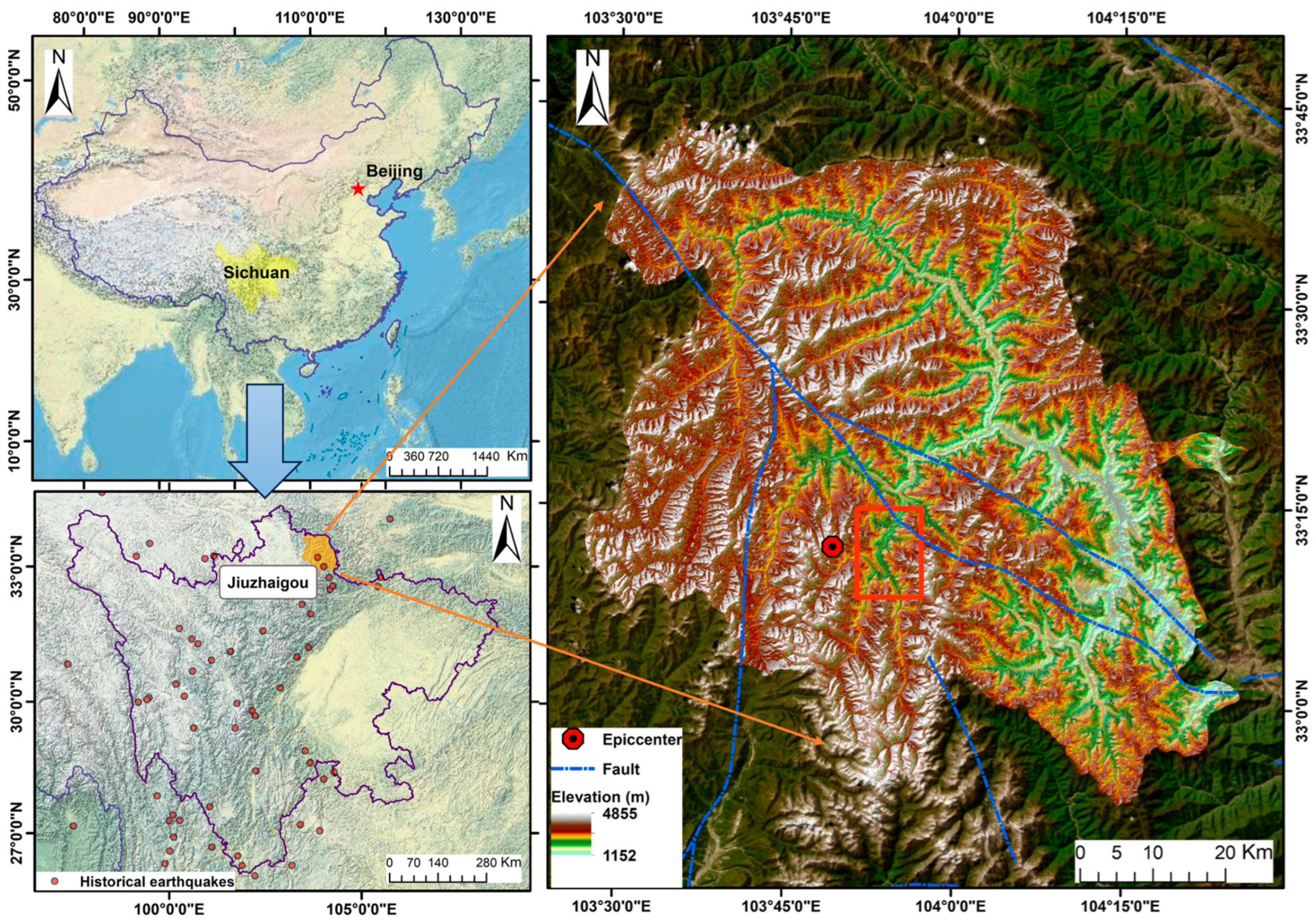

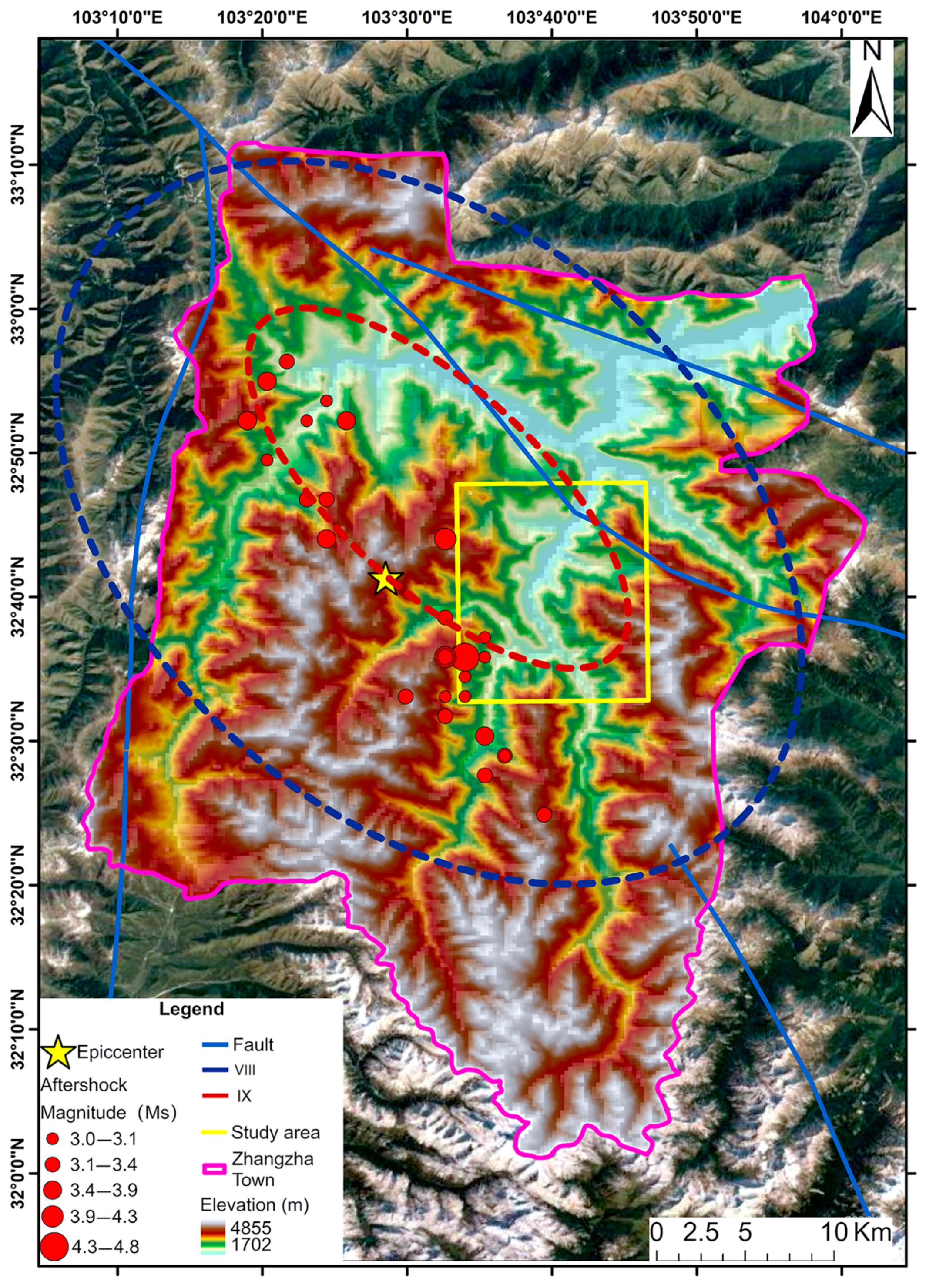

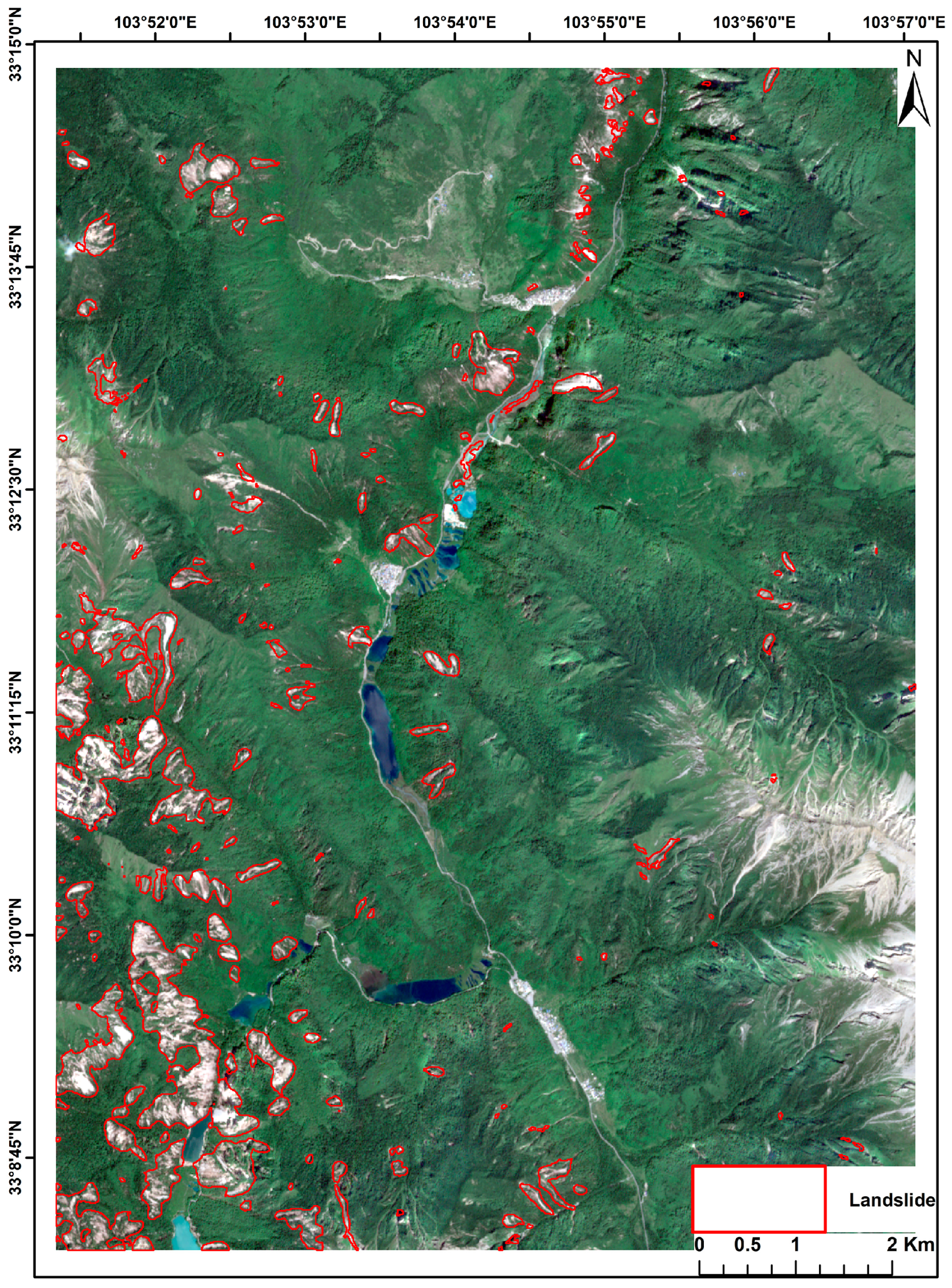

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

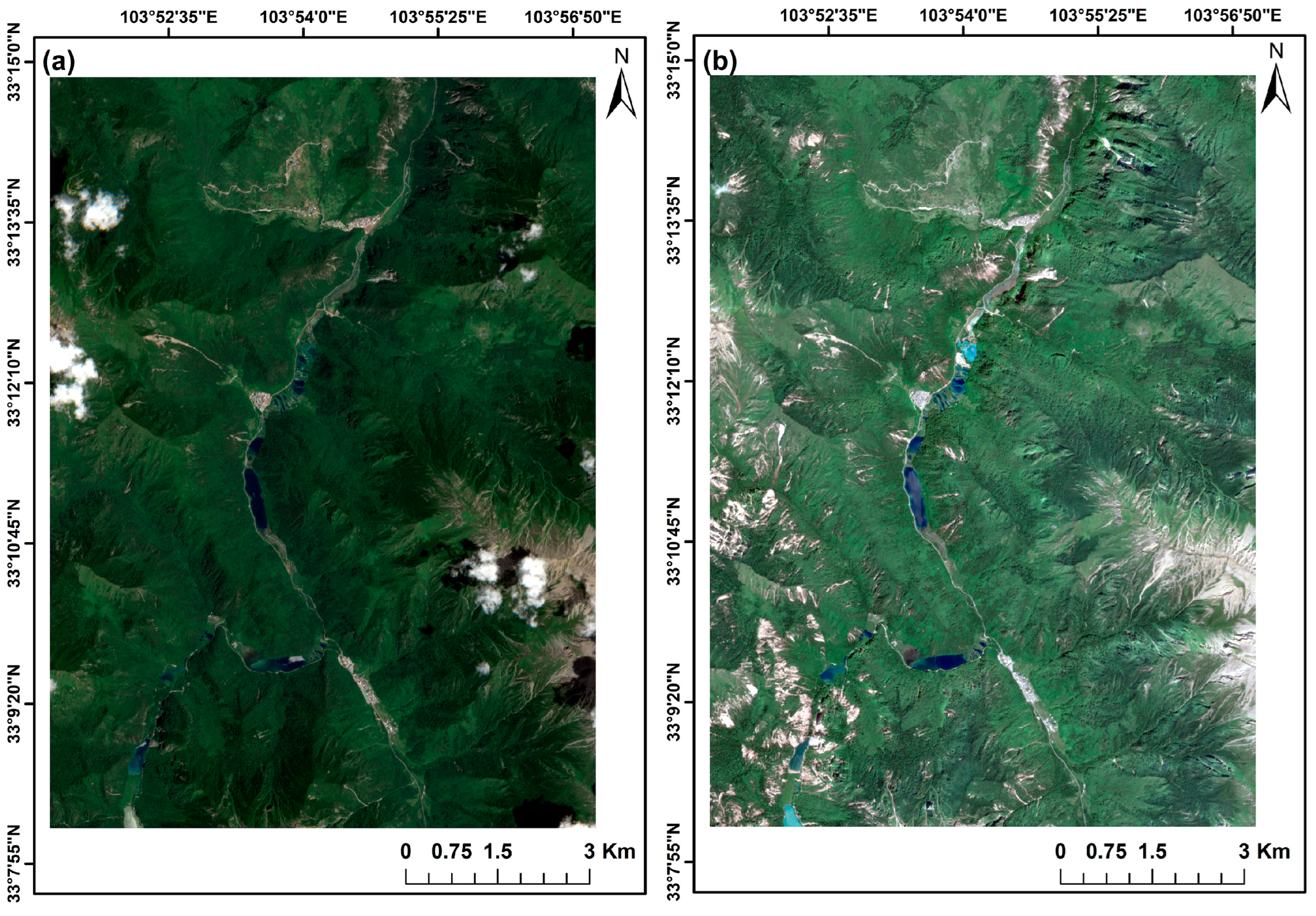

2.2. Data

3. Methods

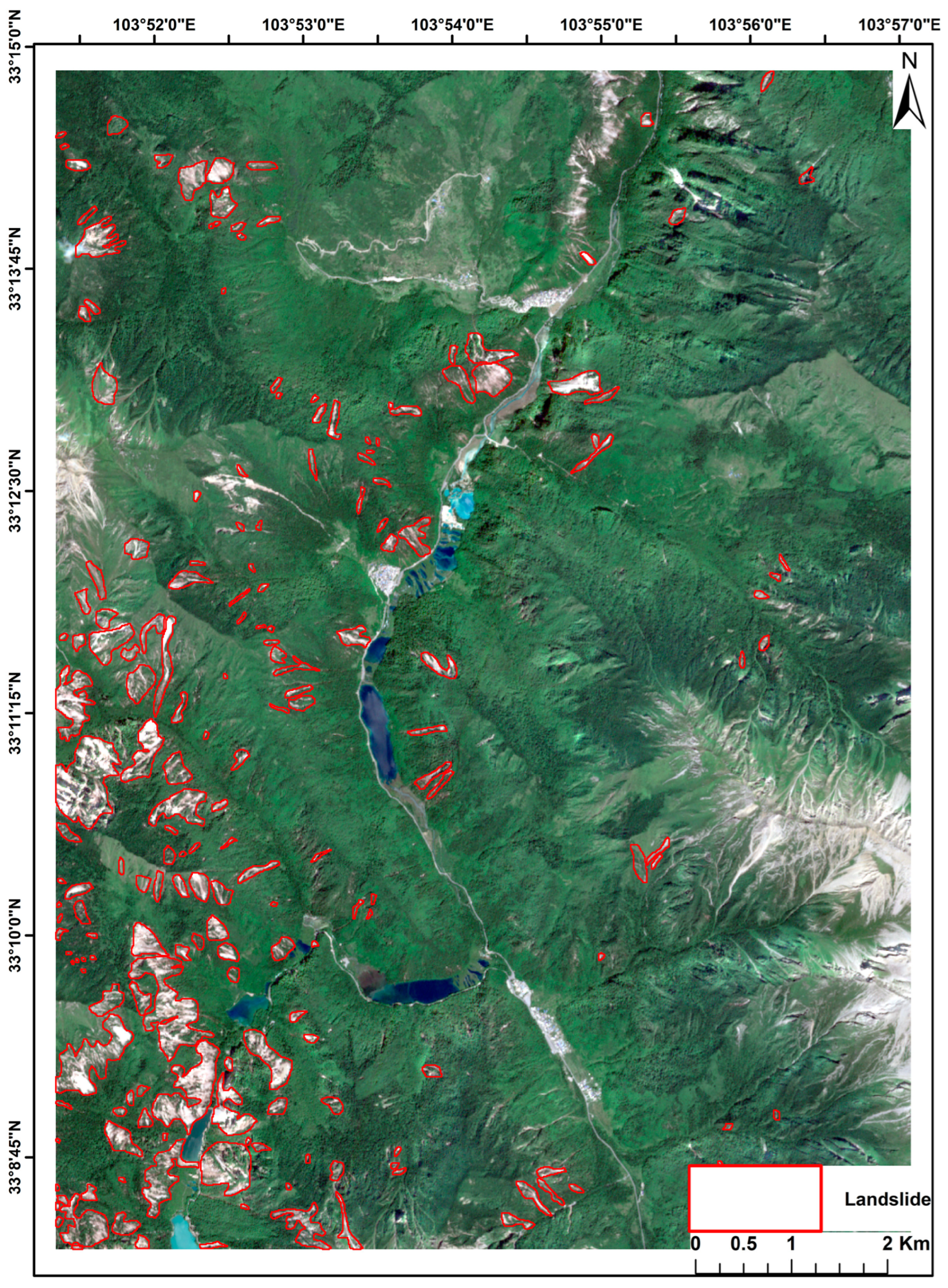

- Employ manual visual interpretation to identify co-seismic landslides in the study area.

- Create a database of co-seismic landslides for the validation of an automated landslide detection method.

- Utilize ID with BR and NDVI images, PK with BR images, along with DL using RGB, FCS, and IDNDVI images for co-seismic landslide detection.

- Evaluate the classification results by using a confusion matrix, with the established database serving as the validation dataset.

- Combine the classification results of each classifier by the WPU method, based on category-specific weights of accuracy evaluation results.

- Conduct a comparative analysis between the combination results of multi-classifier classification and six single classifiers.

3.1. Image Differencing Classification

3.2. PCA-Based K-Means Classification Method

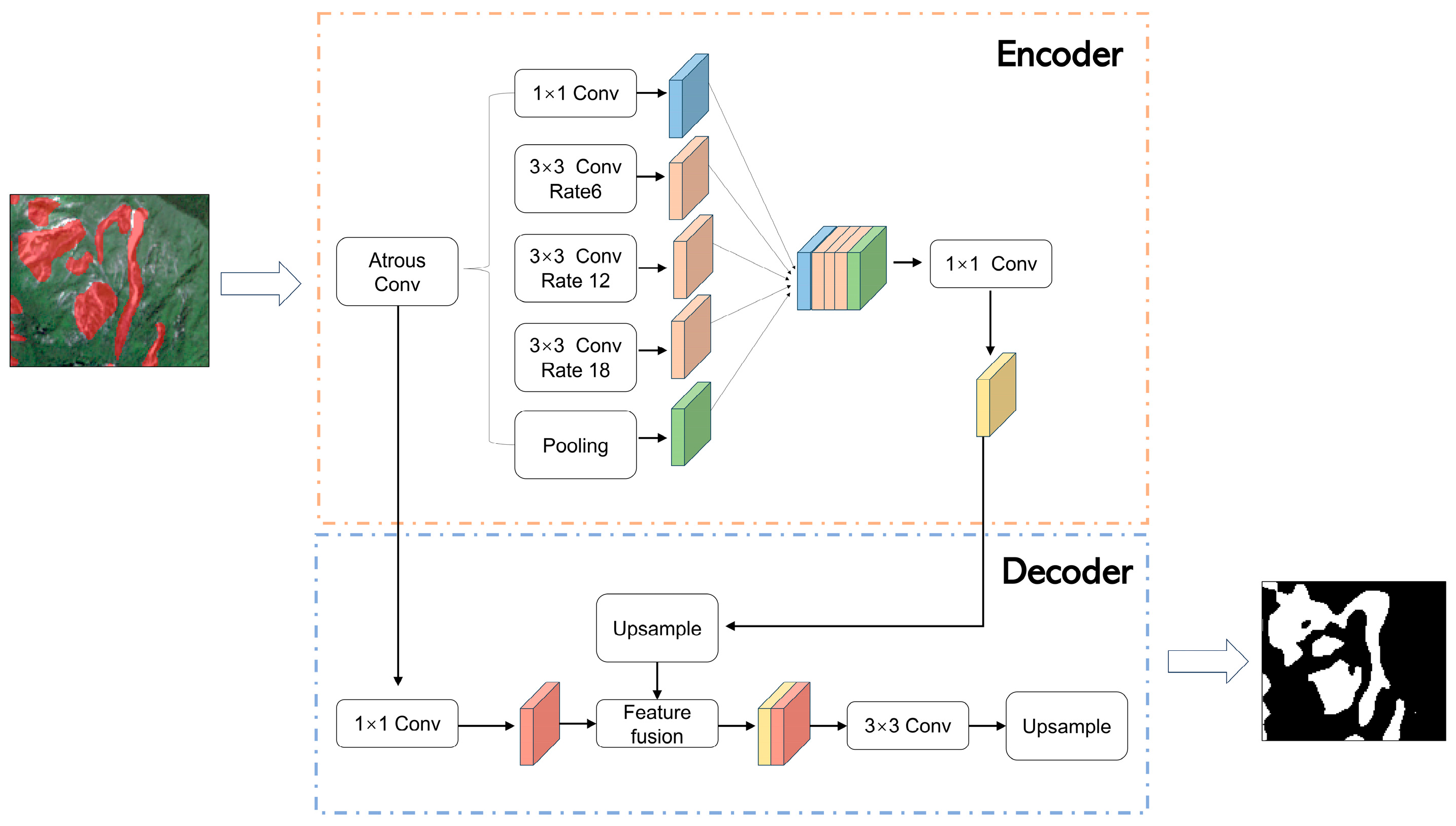

3.3. Deep Learning Classification Method

3.4. Evaluation Metrics for the Accuracy of the Confusion Matrix

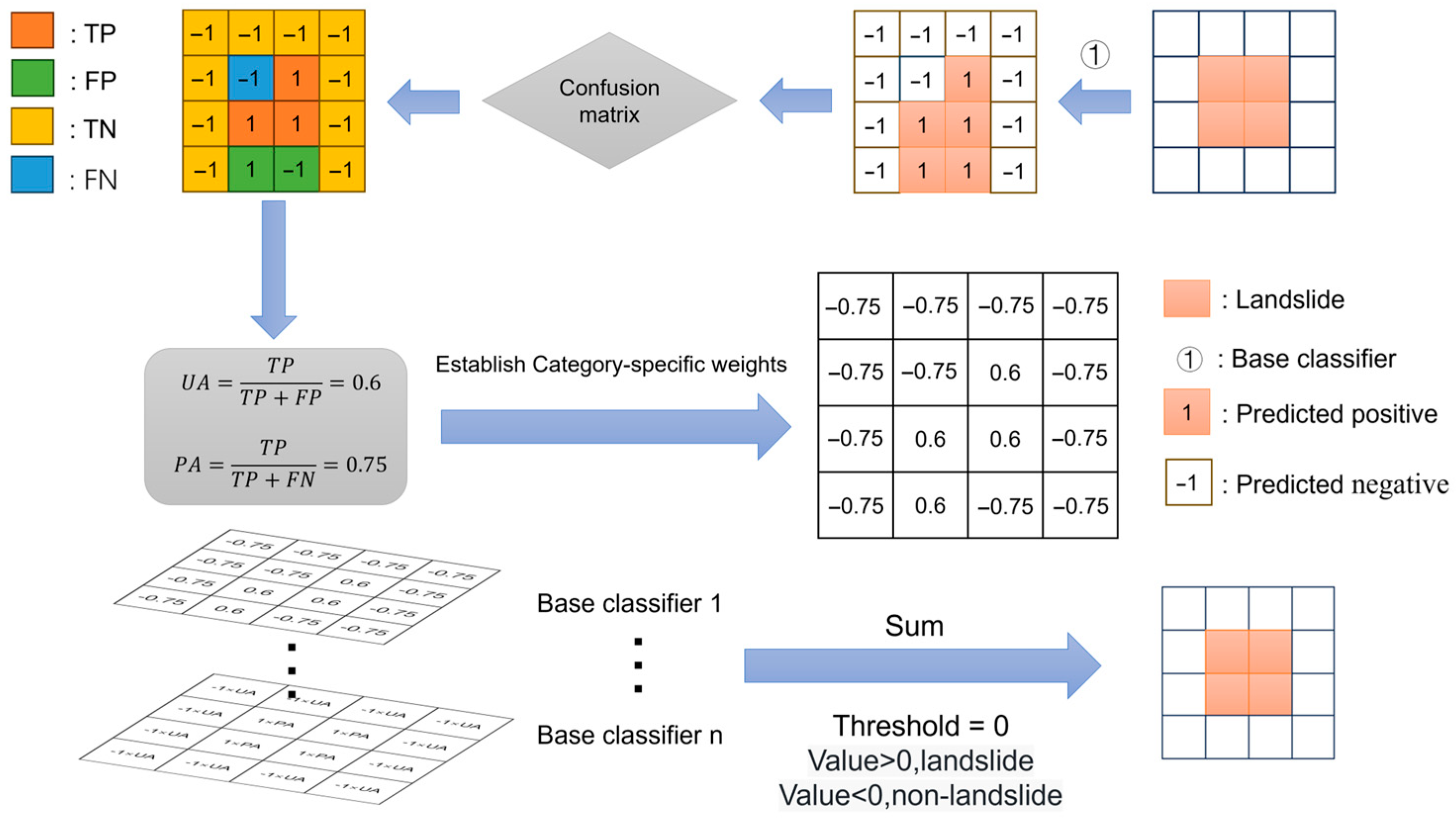

3.5. Multi-Classifier Combination with Weighted Voting

- (1)

- Binarize the classification results of the six base classifiers to obtain the binarized image of co-seismic landslide for each base classifier.

- (2)

- Assign category-specific weights to classifiers based on PA and UA from confusion matrix evaluation.

- (3)

- Apply weights to the binarized images of co-seismic landslides obtained from each classifier to generate weighted images.

- (4)

- Fuse the weighted images and apply a threshold for final classification.

4. Results

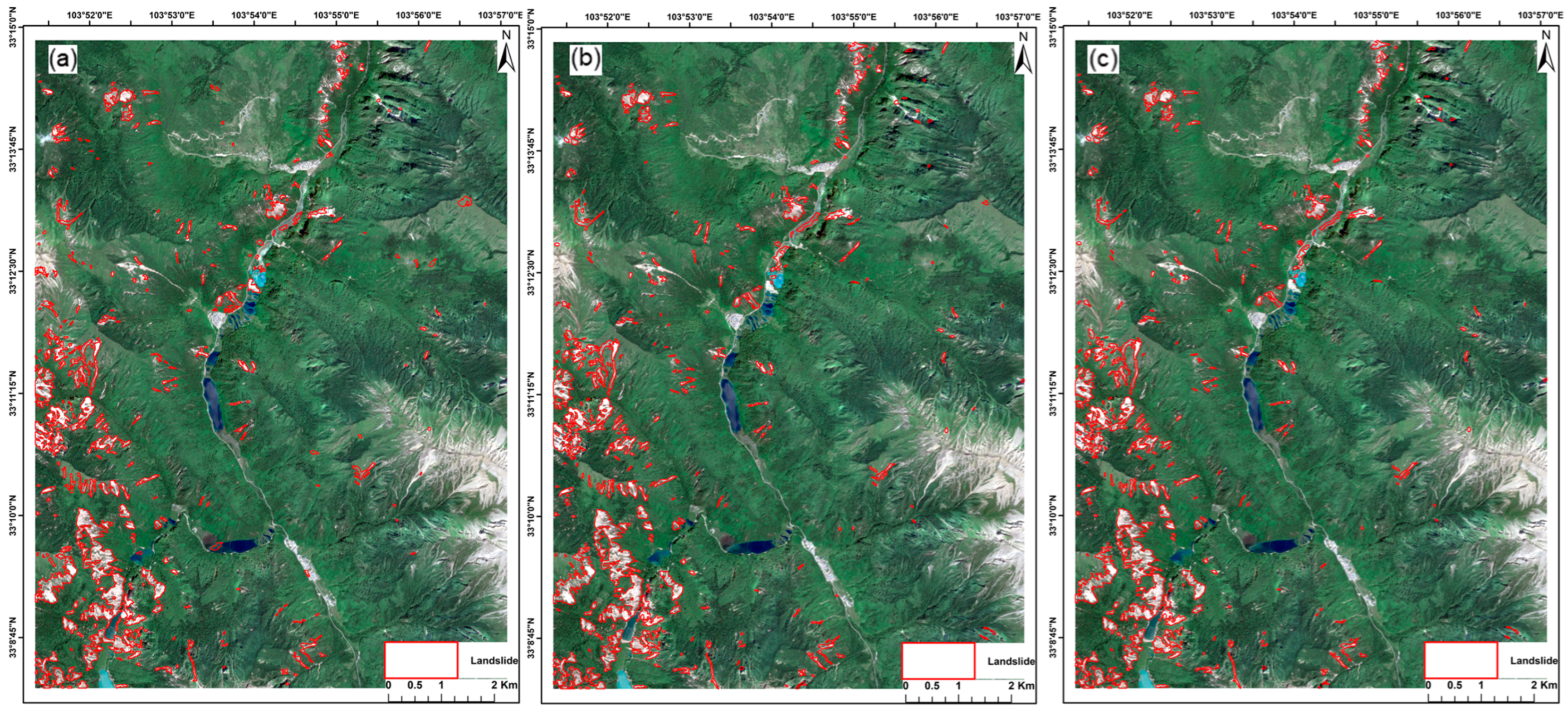

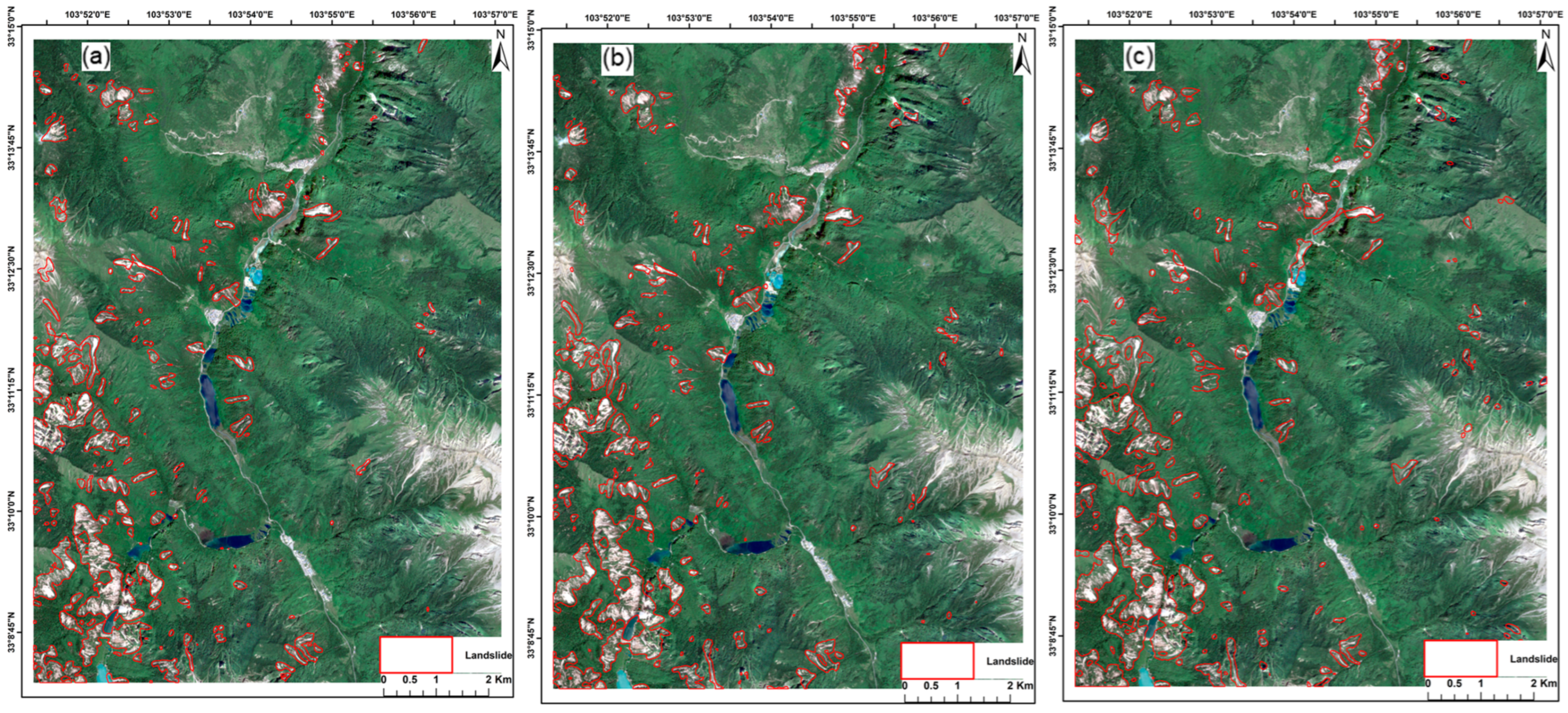

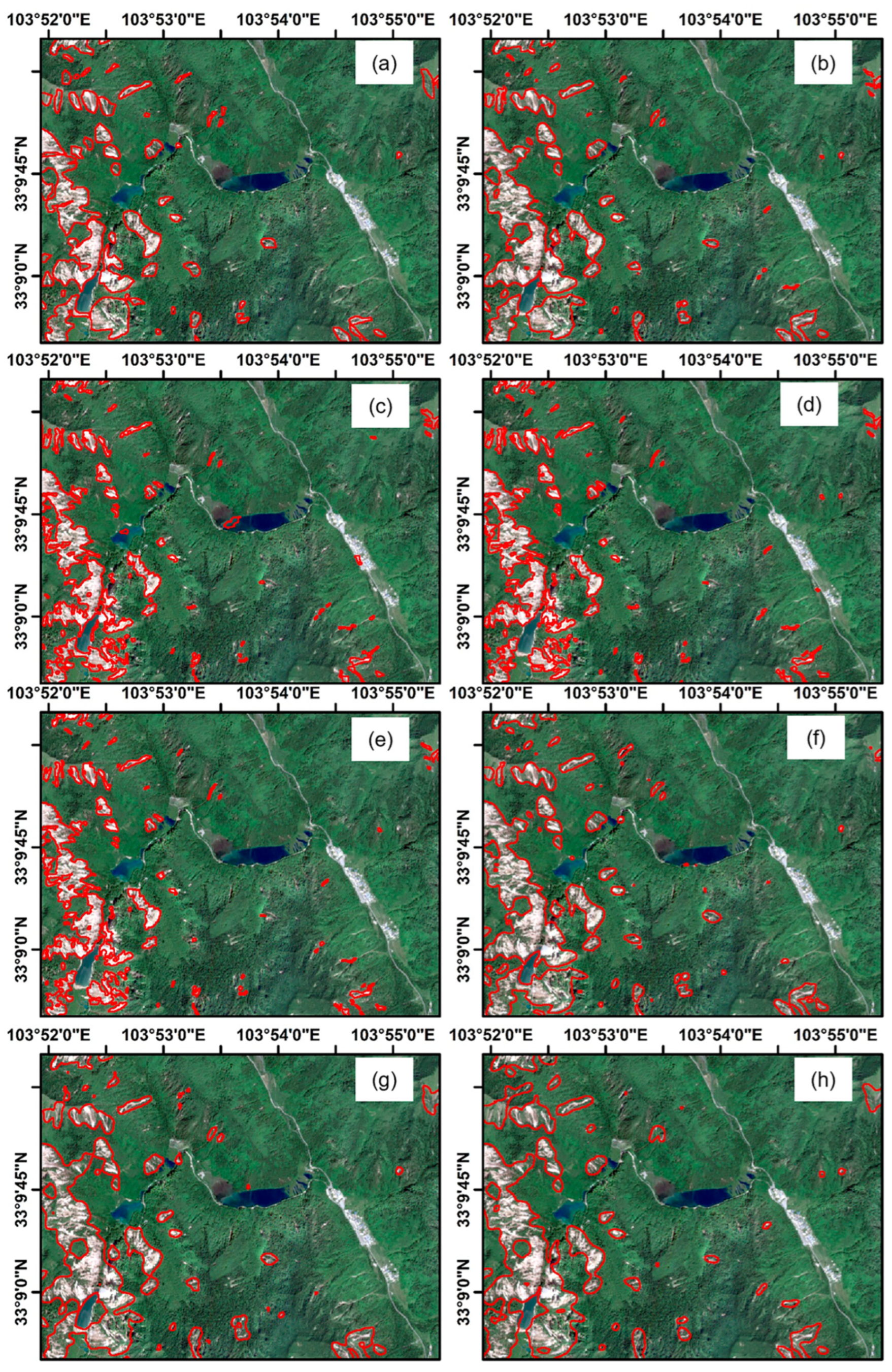

4.1. Accuracy of Single Classifier Results

4.2. Accuracy of WPU

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance of the WPU Method

5.2. Advantages of the WPU Method

5.3. Challenges and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kshetrimayum, A.; H, R.; Goyal, A. Exploring different approaches for landslide susceptibility zonation mapping in Manipur: A comparative study of AHP, FR, machine learning, and deep learning models. J. Spat. Sci. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Xu, S.; Chen, C.; Bao, S.; Wang, Z.; Du, J. 3DCNN landslide susceptibility considering spatial-factor features. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1177891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, P. Landslide hazards triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan, China. Landslides 2009, 6, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, D.K.; Larsen, M.C. Assessing landslide hazards. Science 2007, 316, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefer, D.K. Investigating landslides caused by earthquakes—A historical review. Surv. Geophys. 2002, 23, 473–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, S.; Bozzano, F.; Caporossi, P.; D’Angiò, D.; Della Seta, M.; Esposito, C.; Fantini, A.; Fiorucci, M.; Giannini, L.M.; Iannucci, R.; et al. Impact of landslides on transportation routes during the 2016–2017 Central Italy seismic sequence. Landslides 2019, 16, 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Ma, C.; Liu, W. Landslide Extraction from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery Using Fully Convolutional Spectral–Topographic Fusion Network. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Intrieri, E.; Tofani, V.; Gigli, G.; Raspini, F. Landslide detection, monitoring and prediction with remote-sensing techniques. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Shahabi, H.; Crivellari, A.; Homayouni, S.; Blaschke, T.; Ghamisi, P. Landslide detection using deep learning and object-based image analysis. Landslides 2022, 19, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L. Using multi-temporal remote sensor imagery to detect earthquake-triggered landslides. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2010, 12, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Qiu, H.; Sun, H.; Tang, M. Post-failure landslide change detection and analysis using optical satellite Sentinel-2 images. Landslides 2021, 18, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, F.S.; Calvello, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lacasse, S. Machine learning and landslide studies: Recent advances and applications. Nat. Hazards 2022, 114, 1197–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, F.S.; Santinelli, G.; Herrera Herrera, M. Multi-Regional landslide detection using combined unsupervised and supervised machine learning. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 1015–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, G.; Pirard, E.; Havenith, H.B. Automatic landslide detection from remote sensing images using supervised classification methods. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Barcelona, Spain, 23–28 July 2007; pp. 3014–3017. [Google Scholar]

- Orland, E.; Roering, J.J.; Thomas, M.A.; Mirus, B.B. Deep Learning as a Tool to Forecast Hydrologic Response for Landslide-Prone Hillslopes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Tsangaratos, P.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Liem, N.V.; Trinh, P.T. Comparing the prediction performance of a Deep Learning Neural Network model with conventional machine learning models in landslide susceptibility assessment. CATENA 2020, 188, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.A.; Lee, P.J.; Lum, K.Y.; Loh, C.; Tan, K. Deep Learning for Landslide Recognition in Satellite Architecture. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 143665–143678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, J.; Noro, T.; Sakagami, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshikawa, K.; Hikosaka, S.; Hirata, I. Detection of landslide candidate interference fringes in DInSAR imagery using deep learning. Recall 2018, 90, 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, W. A dual-encoder U-Net for landslide detection using Sentinel-2 and DEM data. Landslides 2023, 20, 1975–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanam, H. Deep Learning in Landslide Studies: A Review. In Progress in Landslide Research and Technology, Volume 1 Issue 2, 2022; Alcántara-Ayala, I., Arbanas, Ž., Huntley, D., Konagai, K., Mikoš, M., Sassa, K., Sassa, S., Tang, H., Tiwari, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Swiztland, 2023; pp. 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liang, W. Landslide extraction model for remote sensing images based on improved DeepLabv3+. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image, Signal Processing, and Pattern Recognition (ISPP 2024), Guangzhou, China, 1–3 March 2024; p. 1318015. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabi, H.; Rahimzad, M.; Tavakkoli Piralilou, S.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Homayouni, S.; Blaschke, T.; Lim, S.; Ghamisi, P. Unsupervised Deep Learning for Landslide Detection from Multispectral Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, D.; Liu, A.; Mei, G. Landslide detection based on deep learning and remote sensing imagery: A case study in Linzhi City. Nat. Hazards Res. 2025, 5, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The research on landslide detection in remote sensing images based on improved DeepLabv3+ method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, R.; Wu, R.; Bao, X.; Liu, G. Landslide detection based on pixel-level contrastive learning for semi-supervised semantic segmentation in wide areas. Landslides 2025, 22, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacinto, G.; Roli, F. Ensembles of Neural Networks for Soft Classification of Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Intelligent Techniques, Aachen, Germany, 8–11 September 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tahraoui, A.; Kheddam, R. LULC Change Detection Using Combined Machine and Deep Learning Classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Advanced Technologies, Signal and Image Processing (ATSIP), Sousse, Tunisia, 11–13 July 2024; pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, E.; Li, Z.; Hao, S. Mapping Coniferous Forest Distribution in a Semi-Arid Area Based on Multi-Classifier Fusion and Google Earth Engine Combining Gaofen-1 and Sentinel-1 Data: A Case Study in Northwestern Liaoning, China. Forests 2024, 15, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh Aydav, P.S.; Minz, S. Multi-view ensemble learning using multi-objective particle swarm optimization for high dimensional data classification. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 8523–8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yu, Z.; Cao, W.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Q. A survey on ensemble learning. Front. Comput. Sci. 2020, 14, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, E.; Uluturk, C.; Ugur, A. A voting-based ensemble deep learning method focusing on image augmentation and preprocessing variations for tuberculosis detection. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 15541–15555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, W. A Review of Ensemble Learning Algorithms Used in Remote Sensing Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncheva, L.I. Combining Pattern Classifiers: Methods and Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. Experiments with a New Boosting Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Bari, Italy, 3–6 July 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Lin, Y.; Tian, Q.; Xu, K.; Jiao, J. A comparison of multiple classifier combinations using different voting-weights for remote sensing image classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 3705–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Wang, X.; Hou, H.; Su, L.; Yu, D.; Wang, H. The earthquake in Jiuzhaigou County of Northern Sichuan, China on August 8, 2017. Nat. Hazards 2018, 90, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, T. Change detection in satellite images using a genetic algorithm approach. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2010, 7, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, L.; Prieto, D.F. Automatic analysis of the difference image for unsupervised change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2000, 38, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Li, G.; Moran, E. Current situation and needs of change detection techniques. Int. J. Image Data Fusion 2014, 5, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelifi, L.; Mignotte, M. Deep Learning for Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images: Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126385–126400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A.F.; Vane, G.; Solomon, J.E.; Rock, B.N. Imaging spectrometry for earth remote sensing. Science 1985, 228, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegler, F.J.; Malila, W.A.; Nalepka, R.F.; Richardson, W. Preprocessing Transformations and Their Effects on Multispectral Recognition. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 13–16 October 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, D.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zheng, P.; Avtar, R.; Chen, X.; Scaringi, G.; Luo, W.; Yunus, A.P. Post-seismic topographic shifts and delayed vegetation recovery in the epicentral area of the 2018 Mw 6.6 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi earthquake. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2024, 48, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Zhang, J.; Sharma, A. Geographic object-based image analysis for landslide identification using machine learning on google earth engine. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiang, X.; Wen, H.; Xiao, J.; Song, C.; Zhou, X.; Yu, J. Improve unsupervised Learning-based landslides detection by band ratio processing of RGB optical images: A case study on rainfall-induced landslide clusters. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2363406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Nie, G.; Cheng, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Gross, L. Building Extraction and Floor Area Estimation at the Village Level in Rural China Via a Comprehensive Method Integrating UAV Photogrammetry and the Novel EDSANet. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qi, W.; Li, X.; Gross, L.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ni, L.; Fan, X.; Li, Z. ARC-Net: An Efficient Network for Building Extraction From High-Resolution Aerial Images. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 154997–155010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gross, L.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, X.; Qi, W. Automatic Building Extraction on High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery Using Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder With Spatial Pyramid Pooling. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 128774–128786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y. DBSANet: A Dual-Branch Semantic Aggregation Network Integrating CNNs and Transformers for Landslide Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Yu, M.; Sun, Y.; Meng, F.; Fan, X. Landslide Detection of High-Resolution Satellite Images using Asymmetric Dual-Channel Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 4091–4094. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Application of the YOLOv11-seg algorithm for AI-based landslide detection and recognition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

| Band | Central Wavelength (μm) | Spatial Resolution (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Blue | 0.490 | 10 |

| 3-Green | 0.560 | 10 |

| 4-Red | 0.665 | 10 |

| 8-NIR | 0.842 | 10 |

| Predicted Positive | Predicted Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | True positive (TP) | False negative (FN) |

| Negative | False positive (FP) | True negative (TN) |

| Method | OA | Kappa | PA | UA | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDBR | 0.9648 | 0.6137 | 0.5197 | 0.8040 | 0.6313 |

| IDNDVI | 0.9669 | 0.6432 | 0.5531 | 0.8179 | 0.6599 |

| PKBR | 0.9663 | 0.6223 | 0.5131 | 0.8462 | 0.6388 |

| DLRGB | 0.9733 | 0.7806 | 0.8912 | 0.7172 | 0.7948 |

| DLFCS | 0.9698 | 0.7614 | 0.9062 | 0.6804 | 0.7772 |

| DLIDNDVI | 0.9546 | 0.6743 | 0.9007 | 0.5691 | 0.6975 |

| Method | PA | UA |

|---|---|---|

| IDBR | 0.4893 | 0.6133 |

| IDNDVI | 0.4901 | 0.8006 |

| PKBR | 0.5131 | 0.8462 |

| DLRGB | 0.9266 | 0.6519 |

| DLFCS | 0.9390 | 0.6314 |

| DLIDNDVI | 0.9250 | 0.6325 |

| Method | OA | Kappa | PA | UA | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPU | 0.9755 | 0.7848 | 0.8311 | 0.7672 | 0.7979 |

| Method | OA | Kappa | PA | UA | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPU | 0.9755 | 0.7848 | 0.8311 | 0.7672 | 0.7979 |

| IDBR | 0.9648 | 0.6137 | 0.5197 | 0.8040 | 0.6313 |

| IDNDVI | 0.9669 | 0.6432 | 0.5531 | 0.8179 | 0.6599 |

| PKBR | 0.9663 | 0.6223 | 0.5131 | 0.8462 | 0.6388 |

| DLRGB | 0.9733 | 0.7806 | 0.8912 | 0.7172 | 0.7948 |

| DLFCS | 0.9698 | 0.7614 | 0.9062 | 0.6804 | 0.7772 |

| DLIDNDVI | 0.9546 | 0.6743 | 0.9007 | 0.5691 | 0.6975 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Z. Co-Seismic Landslide Detection Combining Multiple Classifiers Based on Weighted Voting: A Case Study of the Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in 2017. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010003

Liu Y, Wang X, Zhou J, Zhao Z. Co-Seismic Landslide Detection Combining Multiple Classifiers Based on Weighted Voting: A Case Study of the Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in 2017. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yaohui, Xinkai Wang, Jie Zhou, and Zhengguang Zhao. 2026. "Co-Seismic Landslide Detection Combining Multiple Classifiers Based on Weighted Voting: A Case Study of the Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in 2017" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010003

APA StyleLiu, Y., Wang, X., Zhou, J., & Zhao, Z. (2026). Co-Seismic Landslide Detection Combining Multiple Classifiers Based on Weighted Voting: A Case Study of the Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in 2017. GeoHazards, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010003