Monitoring and Prediction of Differential Settlement of Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Towers in Goaf Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Methodologies of Data Process

2.3.1. Data Preprocessing

2.3.2. SBAS-InSAR Methodology

2.3.3. Fbprophet Algorithm

3. Results

3.1. Deformation Rate Field

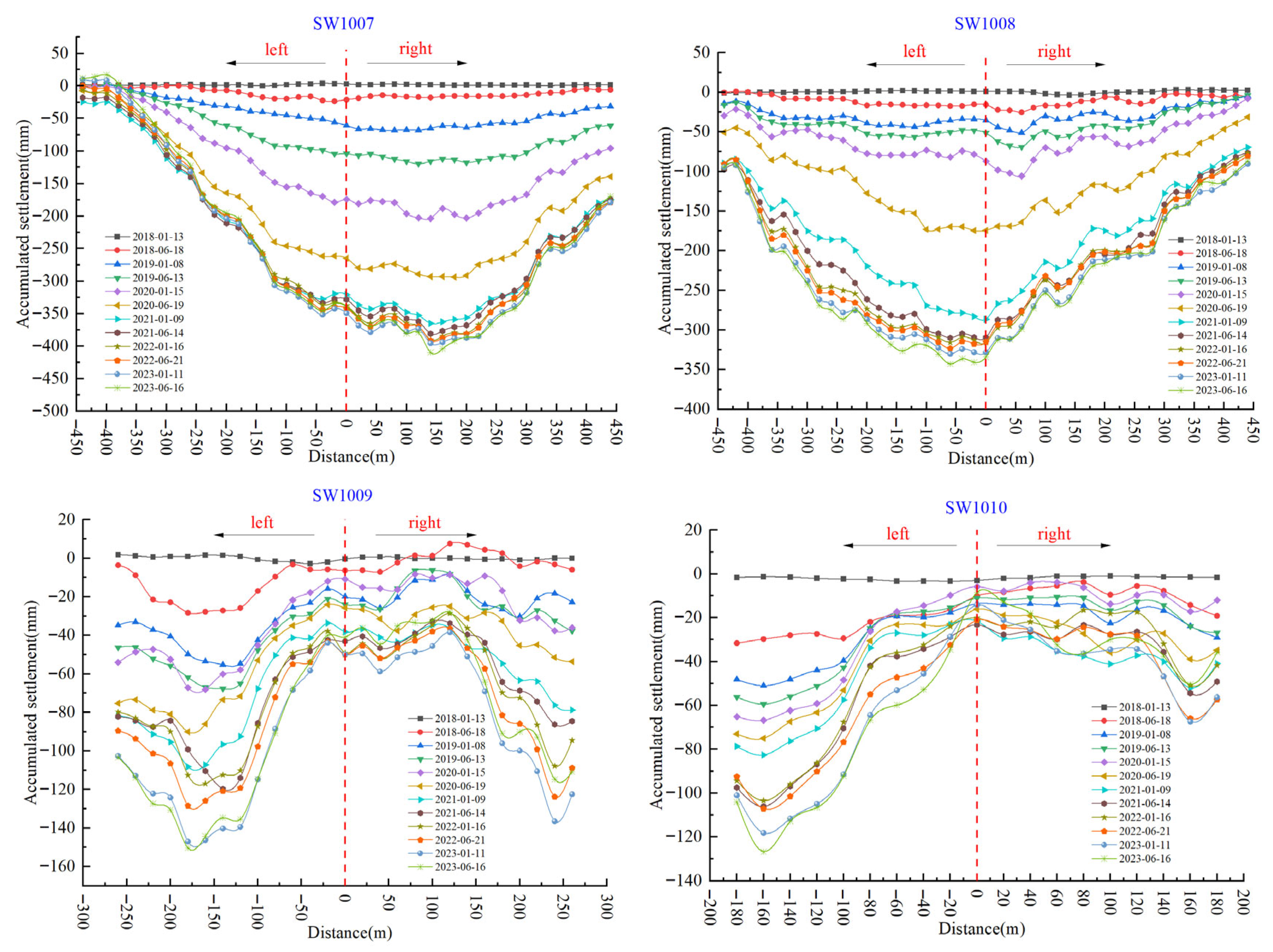

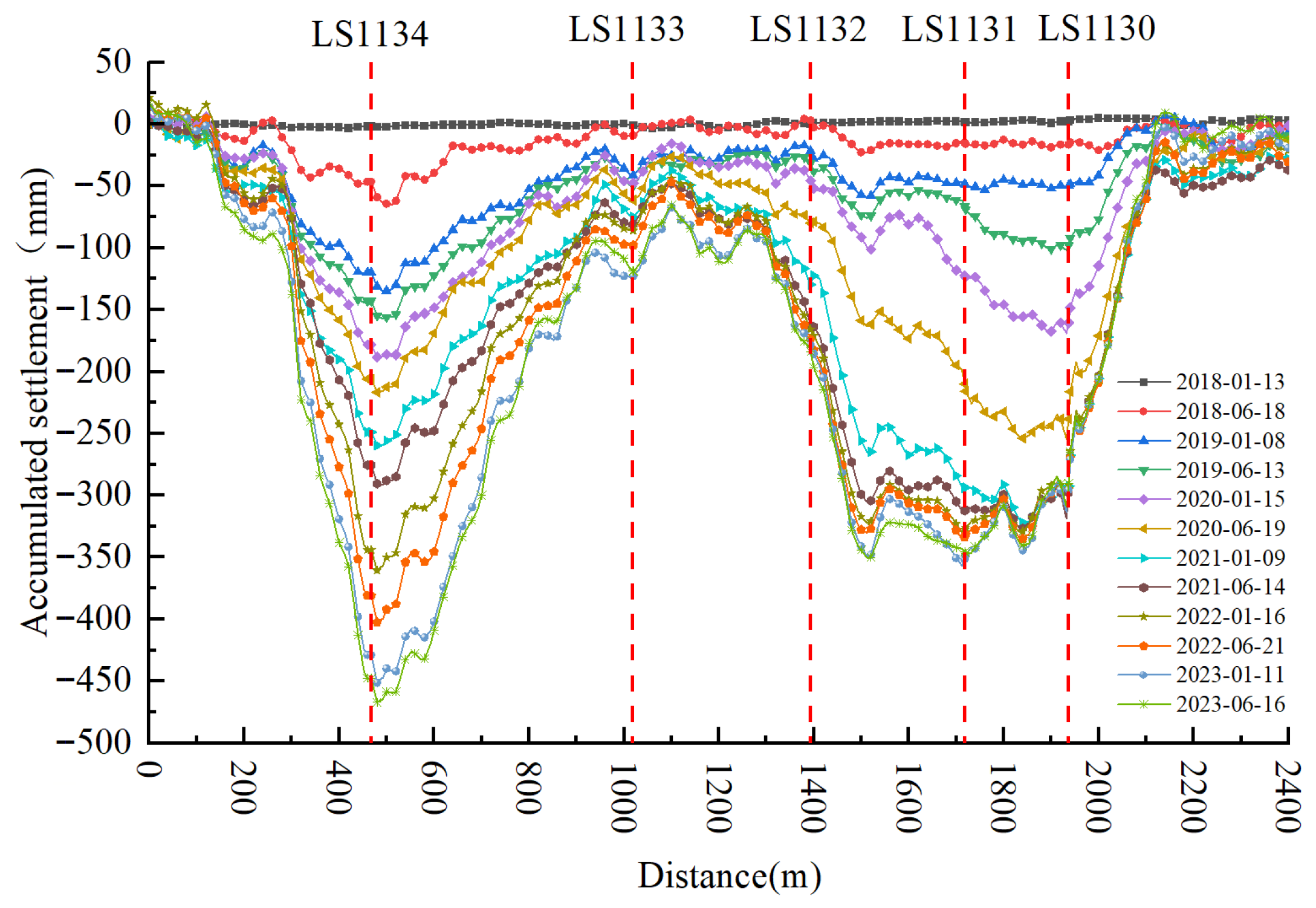

3.2. Surface Deformation Results

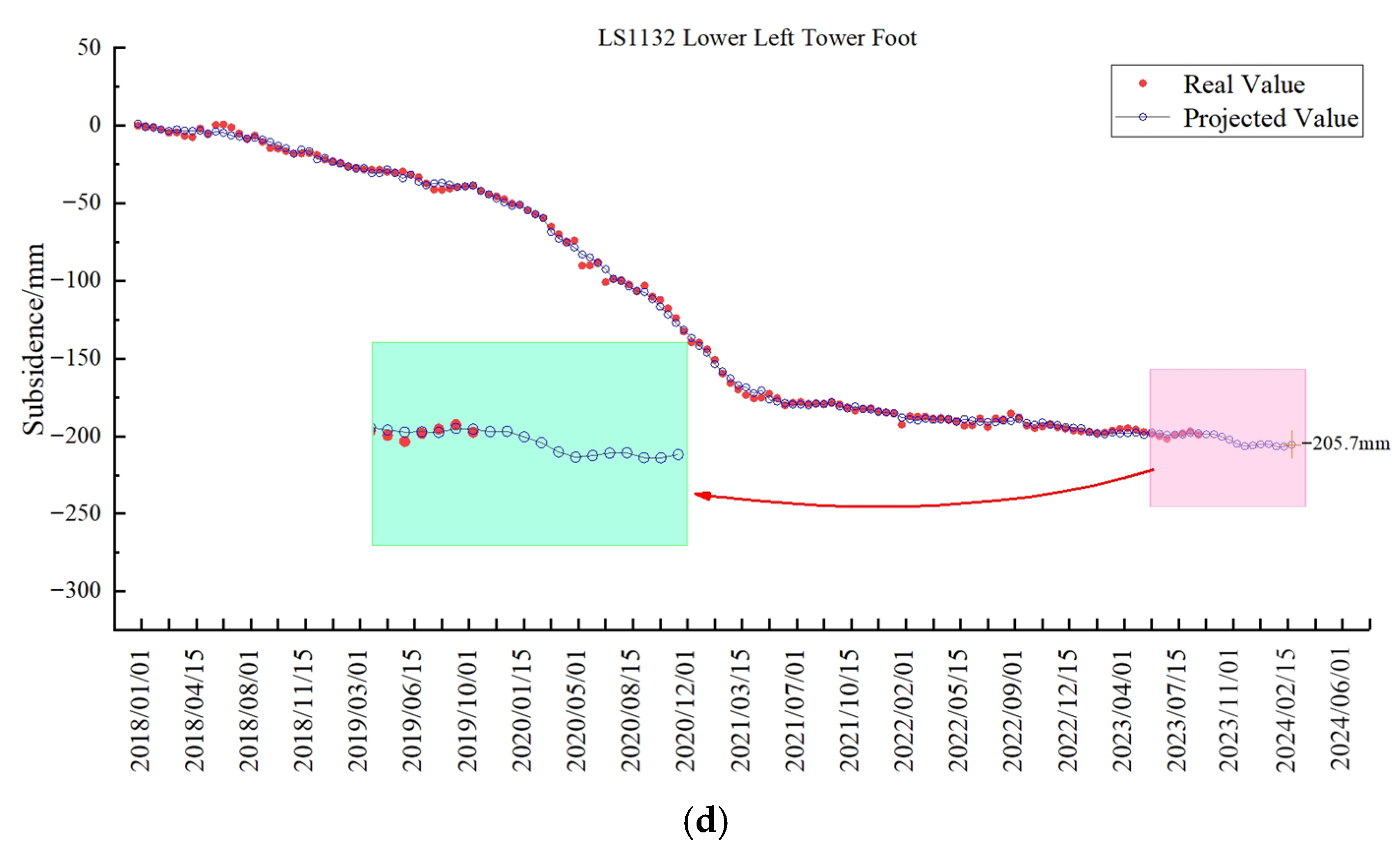

3.3. Prediction Results

4. Discussion

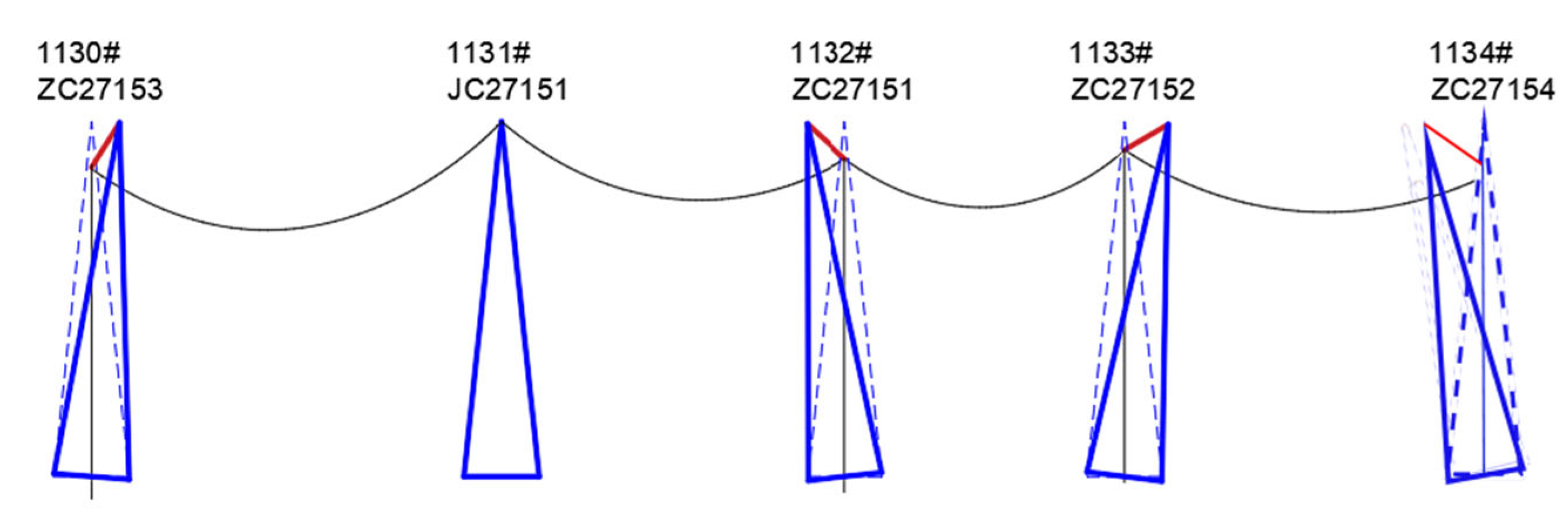

4.1. Tower Tilt Analysis Based on Settlement Trough Method

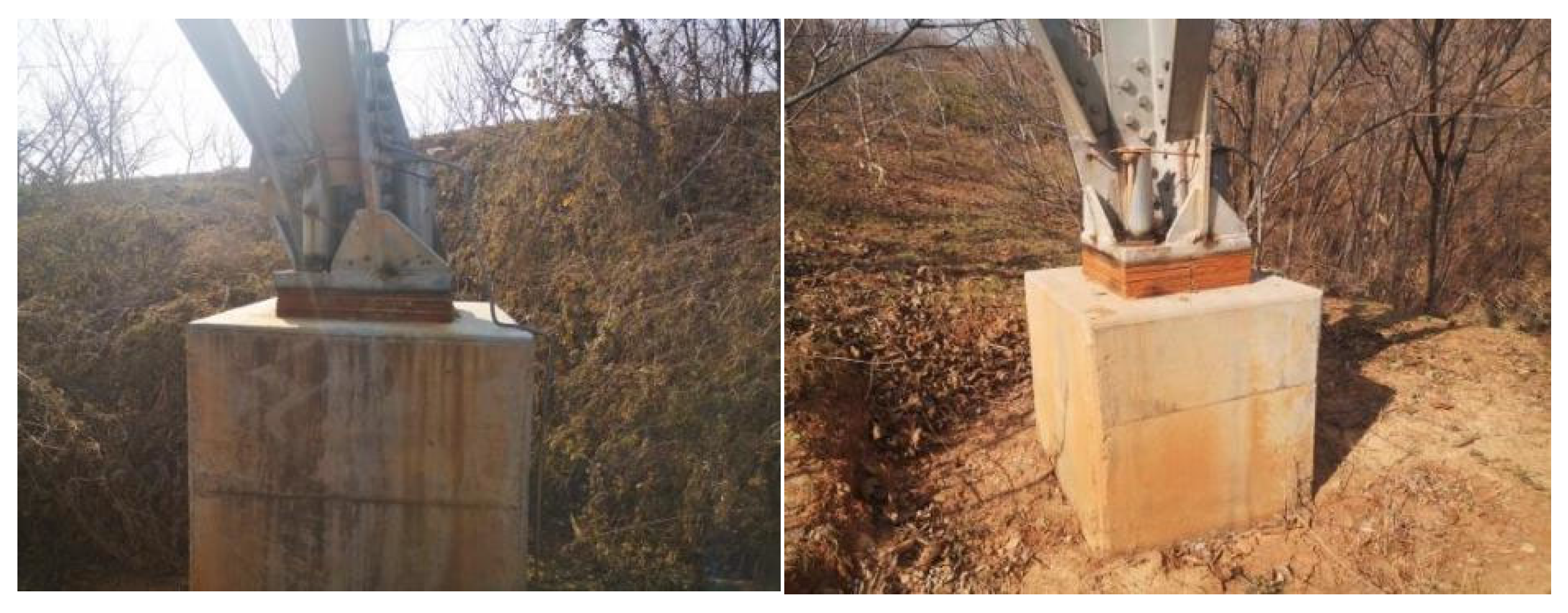

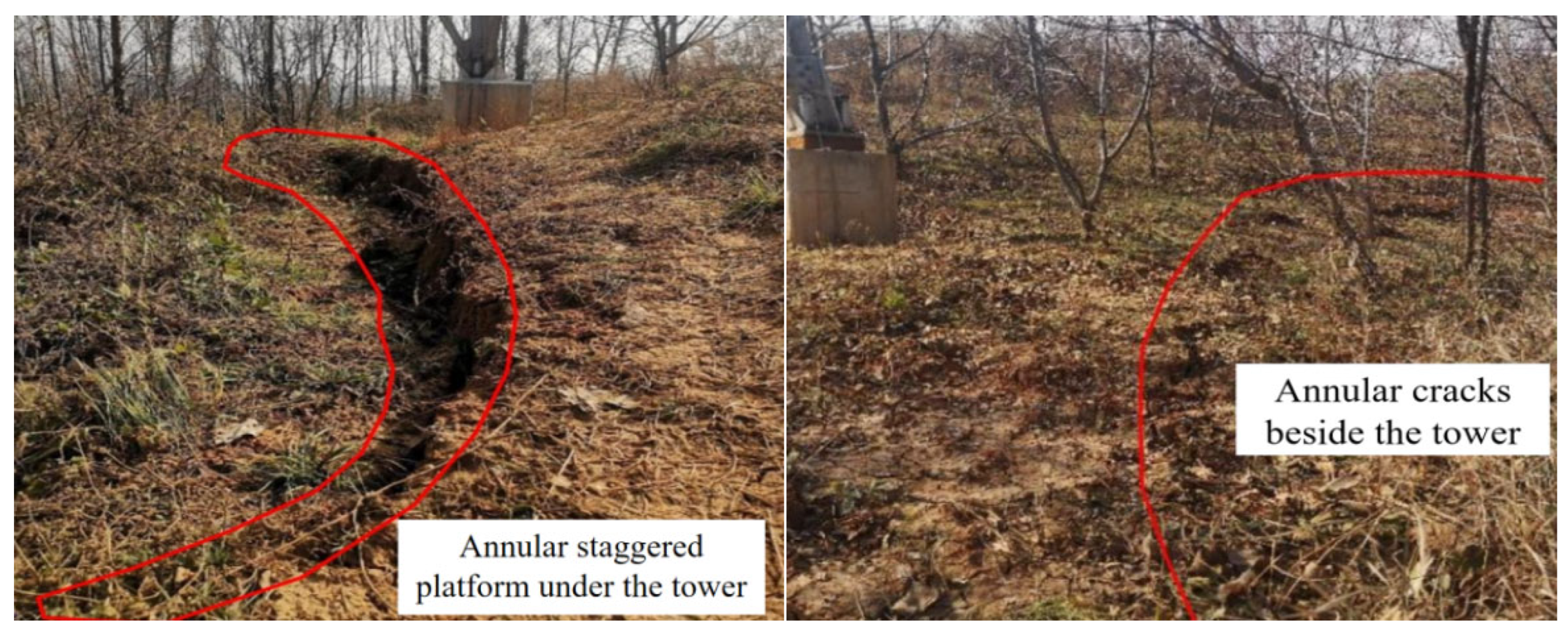

4.2. Field Verification and Analysis

4.3. Mechanism Analysis of Differential Tower Foundation Tilting

4.4. Predictive Model Reliability Validation and Accuracy Assessment

- (1)

- Model reliability validation

- (2)

- Model prediction accuracy assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, R.Z. Safety risk assessment method for forest power corridor based on multi-source data. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2022, 51, 784–794. [Google Scholar]

- LaCommare, K.H.; Eto, J.H. A review of the causes, consequences, and policy implications of electricity outages. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2006, 10, 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen, L.; Lehtomäki, M.; Ahokas, E.; Hyyppä, J.; Karjalainen, M.; Jaakkola, A.; Kukko, A.; Heinonen, T. Remote sensing methods for power line corridor surveys. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 119, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschas, F.; Stiros, S. Measurement of the dynamic displacement of an engineering structure using a geodetic robotic total station. J. Surv. Eng. 2011, 137, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.Q.; Xu, Z.H.; Peng, C.G.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, W.S. A classification method for airborne laser point cloud of high-voltage transmission corridor. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2019, 44, 21–27+33. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, S.; Teizer, J. Mobile 3D mapping for surveying earthwork projects using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) system. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenest, P.; Guerrini, E.; Takita, K. Expliner—Toward a practical robot for inspection of high-voltage lines. In Field and Service Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y. Simulation and test of safety distance for UAV inspection of ±500kV DC transmission line tower. High Volt. Eng. 2019, 45, 426–432. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, A.M.; Pradhan, B.; Tarabees, E. Integrated evaluation of urban development suitability based on remote sensing and GIS techniques: Contribution from the analytic hierarchy process. Arab. J. Geosci. 2011, 4, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallermann, N.; Morgenthal, G. Visual inspection strategies for large bridges using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2014, 10, 834–843. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Roberts, G.W. Detecting bridge dynamics with GPS and triaxial accelerometers. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghoosi, E.; Izadi, I.; Chen, T. Estimation of alarm chattering. J. Process Control 2011, 21, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Shah, S.L.; Xiao, D. Correlation analysis of alarm data and alarm limit design for industrial processes. In Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 30 June–2 July 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 5850–5855. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Varma, A.S.; Singh, A.; Singh, D.; Yadav, B.P. A critical review on the application and problems caused by false alarms. Intell. Commun. Control. Devices 2018, 624, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Intrieri, E.; Raspini, F.; Fumagalli, A.; Lu, P.; Del Conte, S.; Farina, P.; Allievi, J.; Ferretti, A.; Casagli, N. The Maoxian landslide as seen from space: Detecting precursors of a failure with Sentinel-1 data. Landslides 2018, 15, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. A review of the use of helicopters for overhead power line inspection. IEEE Proc. Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2002, 149, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, A.; Rabah, M. A review of power line inspection systems. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2015, 10, 2341–2348. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.H. Discussion of helicopter inspection for EHV transmission lines. Fujian Power Electr. Eng. 2004, 24, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Li, H.F.; Wang, W. Analysis of helicopter patrol application prospect in China’s UHV grid. High Volt. Eng. 2006, 32, 45–46+55. [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo, D.; Cerritelli, F.; Agostini, S.; Bello, S.; Lavecchia, G.; Brozzetti, F. Integrating Post-Processing Kinematic (PPK)-Structure-from-Motion (SfM) with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Photogrammetry and Digital Field Mapping for Structural Geological Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2022, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Research on Structure and Precise Control of High-Voltage Line Inspection Robot. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.M.; Huang, Z.T.; Wan, R.Y. Application of UAV low-altitude photography technology in intelligent inspection of overhead transmission lines. China Plant Eng. 2025, 13, 183–185. [Google Scholar]

- Portugal, D.; Almeida, L.; Santos, L. A survey on multi-robot patrolling algorithms. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2014, 410, 383–397. [Google Scholar]

- Metni, N.; Hamel, T. A UAV for bridge inspection: Visual servoing control law with orientation limits. Autom. Constr. 2007, 17, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Wang, J. Automatic detection of transmission towers in aerial images based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 5197–5208. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Y.; Sawaya, K.E.; Loeffelholz, B.C.; Bauer, M.E. Land cover classification and change analysis of the Twin Cities (Minnesota) metropolitan area by multitemporal Landsat remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 98, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Q.J.; Jiang, X.W.; Zhang, L.S.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, F.; Qian, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhai, S.; Zhou, T. Analysis of electric field distribution at acquisition terminal of portable intelligent patrol video collection for transmission line based on finite element method. High Volt. Appar. 2018, 54, 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Carle, M.V.; Wang, L.; Sasser, C.E. Mapping freshwater marsh species distributions using WorldView-2 high-resolution multispectral satellite imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 4698–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Automatic detection of power line insulator defects based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar]

- Jwa, Y.; Sohn, G. A multi-pass, multi-resolution approach for 3D modeling of power line corridors from airborne LiDAR data. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, B.; Yao, J.; Hu, S.; Yang, F. Refined Simulation of Strong Convective Winds in Jiangsu and Its Application to Tower Level Disaster Prevention and Forecast of Power Grid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 224, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, M.; Bahreinian, S.; Riasi, A. Predictive modeling for savonius hydrokinetic turbine performance: A machine learning investigation. Energy 2025, 340, 139109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Hernández, E.; Ibarra-González, S.; De-León-Escobedo, D. Collapse mechanisms of power towers under wind loading. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2017, 13, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, C.; Wei, L.; Guo, Z.; Jia, P.; Wang, W.; Gao, Y. Slope deformation prediction based on MT-InSAR and Fbprophet for deep excavation section of South-North Water Transfer Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, X.; Lei, J. Monitoring of wind erosion in the southern Aral Sea using SBAS-InSAR technology. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2025, 13, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Pan, B.; Hussain, W.; Sajjad, M.M.; Ali, M.; Afzal, Z.; Abdullah-Al-Wadud, M.; Tariq, A. Integrated PSInSAR and SBAS-InSAR analysis for landslide detection and monitoring. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 139, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.B.; Zhao, C.; Kakar, N.; Chen, X. SBAS-InSAR monitoring of landslides and glaciers along the Karakoram Highway between China and Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Chi, S.; Wei, T.; Wang, X. DPIM-Based InSAR Phase Unwrapping Model and a 3D Mining-Induced Surface Deformation Extracting Method: A Case of Huainan Mining Area. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 25, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H.M.; Ge, L.; Du, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, C. Satellite radar interferometry for monitoring subsidence induced by longwall mining activity using Radarsat-2, Sentinel-1 and ALOS-2 data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 61, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, Z.W.; Ding, X.L.; Zhu, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q. Resolving three-dimensional surface displacements from InSAR measurements: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 133, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Letham, B. Forecasting at Scale. Am. Stat. 2018, 72, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tower No. | Tower Type | Height (mm) | Total Height (mm) | Lateral Tilt (‰) | Monitoring Benchmark | Relative Settlement (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1130 | ZC27153 | 72,000 | 88,500 | Right 0.54‰ | Leg D | Legs A, B, C settled by 22, 42, 114 |

| 1132 | ZC27151 | 66,000 | 82,500 | Left 3.64‰ | Leg C | Legs A, B, D settled by 106, 21, 85 |

| 1133 | ZC27152 | 66,000 | 82,500 | Left 0.48‰ | Leg A | Legs B, C, D settled by 4, 17, 16 |

| 1134 | ZC27154 | 78,000 | 94,500 | Left 0.69‰ | Leg A | Legs B, C, D settled by 14, 24, 23 |

| Sample Number | 1130a | 1130b | 1130c | 1130d | 1132a | 1132b | 1132c | 1132d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (mm) | |||||||||

| maximum | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 | |

| minimum | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | |

| NO. | R | RMSE/mm |

|---|---|---|

| 1130a | 0.999 | 1.36 |

| 1130b | 0.998 | 2.17 |

| 1130c | 0.989 | 1.14 |

| 1130d | 0.998 | 1.18 |

| 1132a | 0.999 | 0.54 |

| 1132b | 0.998 | 0.78 |

| 1132c | 0.997 | 0.62 |

| 1132d | 0.998 | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Jing, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, L.; Mai, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, Z. Monitoring and Prediction of Differential Settlement of Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Towers in Goaf Areas. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040083

Zhou Y, Jing Y, Zheng Y, Ding L, Mai Z, Guo Y, Wu D, Wang Z. Monitoring and Prediction of Differential Settlement of Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Towers in Goaf Areas. GeoHazards. 2025; 6(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yi, Ying Jing, Yuesong Zheng, Laizhong Ding, Zhiyao Mai, Yaxing Guo, Dongya Wu, and Zhengxi Wang. 2025. "Monitoring and Prediction of Differential Settlement of Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Towers in Goaf Areas" GeoHazards 6, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040083

APA StyleZhou, Y., Jing, Y., Zheng, Y., Ding, L., Mai, Z., Guo, Y., Wu, D., & Wang, Z. (2025). Monitoring and Prediction of Differential Settlement of Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Towers in Goaf Areas. GeoHazards, 6(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards6040083