1. Introduction

For many years, it was widely believed that earthquakes could not be predicted [

1]. However, statistical analysis has revealed three notable precursory phenomena [

2] preceding the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, which registered a magnitude of 9.0 [

3,

4]. These precursors were as follows:

A shortening of the time interval between seismic events, indicating an increase in frequency.

A rise in magnitude, accompanied by a significant increase in the standard deviation of the normally distributed magnitude data—suggesting a heightened likelihood of large-scale earthquakes.

Immediately prior to the main event, a sequence of unusually high-magnitude earthquakes occurred, resulting in an improbably elevated average magnitude.

These findings suggest that the potential for predicting major seismic events may be considerable. Nevertheless, such precursors have thus far been reported primarily in connection with exceptionally large earthquakes. This naturally raises the question of whether comparable patterns might also be discernible in smaller seismic events. With respect to the timing of major earthquakes, some studies have introduced the concept of “natural time” to analyse phenomena such as magnetic field changes [

5,

6,

7]. Other investigations have explored geodetic, electromagnetic, ionospheric, and macroscopic anomalies [

8]. In the present work, we adopt a more restrained approach, considering only the timing of earthquakes and their magnitude.

In Japan, moderate earthquakes—classified as magnitude 5 to 6—occur with notable frequency [

9]. For instance, in 2002, there were sixty magnitude 5 earthquakes, thirteen magnitude 6 earthquakes, and one magnitude 7 earthquake [

9]. While not all of these result in significant ground motion or human casualties, the ability to predict such events would undoubtedly enhance disaster preparedness [

3,

10]. This is particularly relevant given that many individuals remain unaware of the full implications of an earthquake. Should a major event occur, it would likely result in widespread power outages, disrupting internet access, telecommunications, and broadcast services. Food distribution would be impeded, as supermarkets without electricity would be unable to operate tills or refrigeration units. Petrol supplies would also be affected. Foreknowledge of such an event would allow for a degree of pre-emptive action.

Most recently, a major earthquake (M7.6) struck the Noto Peninsula in January 2024 [

11]. The damage caused by this event remains unresolved, and full recovery has yet to be achieved. This study investigates whether precursory phenomena were present in this case, as well as in several other recent seismic events.

2. Materials and Methods

All data utilised in this study were obtained from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) [

9,

12,

13]. Two primary sources were employed:

Periodical reports published in PDF format, which comprehensively document all perceptible seismic events occurring within Japan [

9].

Epicentral catalogue data provided in CSV format [

12,

13], detailing the time, location, and magnitude of all detected earthquakes.

All this data has been utilised without applying any filters, such as by magnitude. Ignoring portions of the data constitutes falsification, and no such practices have been employed here. It should be noted that the catalogue data include a substantial number of events originating outside Japan, particularly those of higher magnitudes. For instance, approximately half of the entries for magnitude 5 and 6 earthquakes pertain to overseas events, i.e., outside of Japan. Efforts were made to exclude such non-domestic data wherever feasible. Which of the several earthquakes was considered the mainshock was determined by the JMA. As of October 2025, the most recent full-year catalogue available covered the year 2022 [

12]. More recent data are organised on a daily basis, rendering them less amenable to large-scale analysis [

13]. Consequently, representative samples from selected days were extracted for inclusion.

Unless otherwise indicated, magnitude distributions were derived from the periodical reports, which focus exclusively on earthquakes felt within Japan. In contrast, earthquake frequency data were sourced from the comprehensive catalogues [

12], as the regional limitation inherent in the periodicals results in a reduced number of data points.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2 [

14]. The scripts employed for data processing and visualisation were previously published in an earlier study [

2].

3. Results

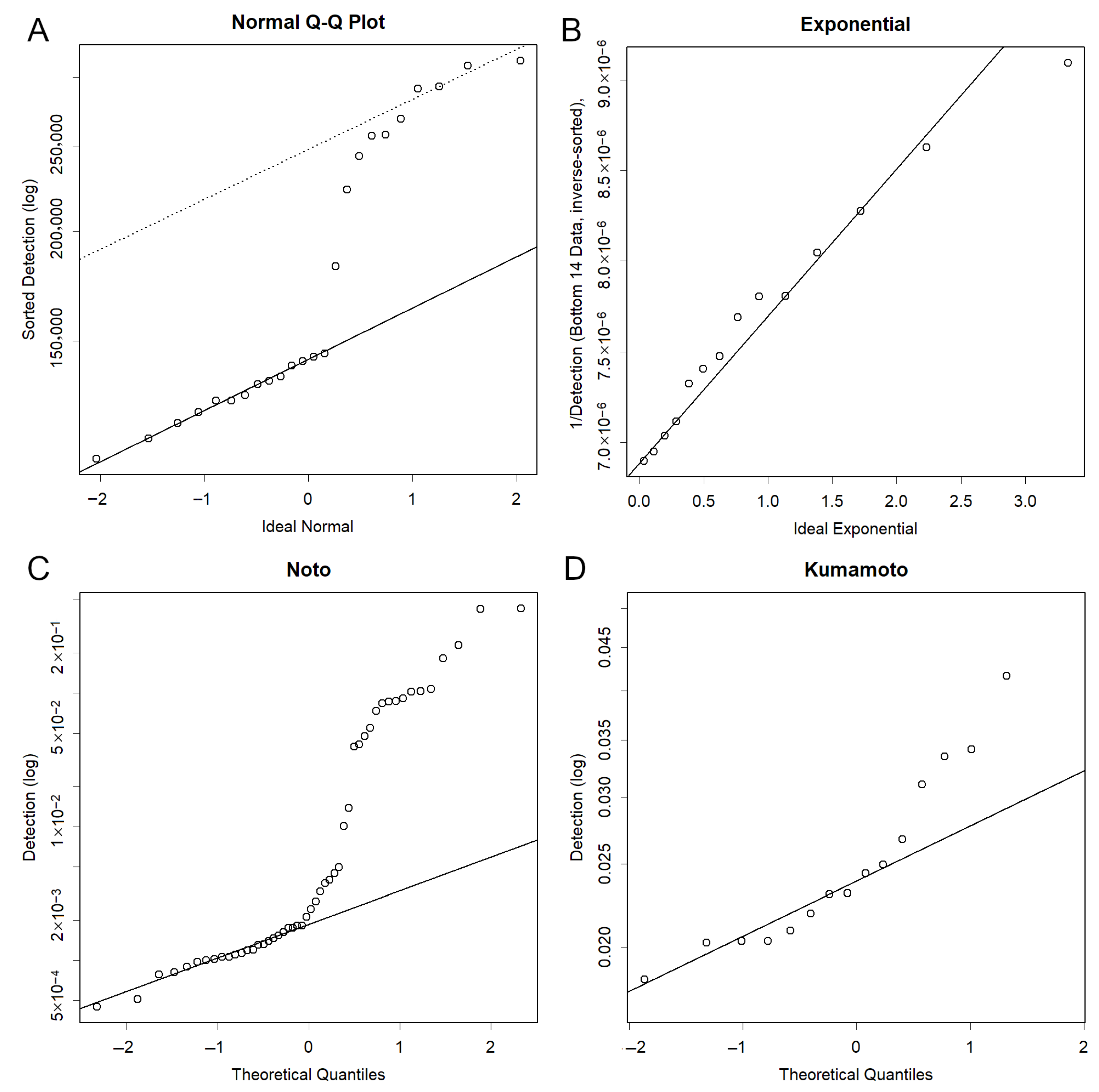

First, we examined the nature of the data. The distribution of earthquake occurrences was fundamentally lognormal. This property was confirmed even when locations were divided by mesh, for example [

15]. However, the distribution varied somewhat by year, with the number of occurrences clearly increasing since 2016. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the data separately by decade. In this paper, the distribution of the data plays a crucial role. Readers less familiar with modern statistics may find

Supplement S1 and its explanatory text helpful for understanding. For instance, this figure illustrates a method for comparing data quantiles, where the observed quantiles are compared against theoretical values. This reveals the distribution model that best fits the data.

Figure 1 presents the number of earthquakes recorded in the catalogue. The lower 14 data points exhibit an approximately lognormal distribution. Since the 2011 Tohoku earthquake—and particularly from 2016 onwards—the number of recorded events has been markedly higher than during the preceding, quieter years. This increase may be partially attributable to advancements in earthquake detection technologies following the Tohoku event, including the implementation of GPS and submarine cable systems [

16]. Recently, this increase appears to have stabilised, becoming a lognormal distribution with σ similar to that observed previously (

Figure 1A, dotted line).

Figure 2A illustrates the regions examined in this study, with the relevant areas shaded in blue or aqua. Several of these regions encompass substantial oceanic zones.

Figure 2B presents the number of earthquakes recorded in the catalogue.

3.1. The 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake

The 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake registered a magnitude of 7.6 [

11], approximately 1/125th of the energy release of the M9.0 Tohoku earthquake [

3,

4]. Were the three precursory characteristics identified in the Tohoku event also present in this case?

Figure 3A displays the proportion of earthquakes occurring in the Noto region relative to the entire catalogue. This region constitutes roughly 0.5% of Japan’s total land area. If seismic events were uniformly distributed and detection sensitivity was consistent nationwide, one would expect a similar proportion of earthquakes. In practice, however, the number of events—excluding swarm activity—generally follows a lognormal distribution (see

Figure 1C,D), with the mean significantly below 0.5% (

Figure 3A). The solid black line in the figure represents values three standard deviations above the mean. A notable increase in earthquake proportion is observed several years prior to the mainshock. The

p-value associated with the 3σ threshold is approximately 0.13%. The

p-value indicates the probability of obtaining a value more extreme than a specified threshold. If a given lognormal distribution consistently produces results within this range, the probability of it exceeding 3σ by chance is only approximately this. Should it consistently exceed this threshold, it should be considered evidence that the distribution has changed.

Additionally, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake occurred in the same region in 2007. In both instances, a seismic swarm was observed approximately six months prior to the mainshock (

Figure 2B and

Figure 3A), indicating a shortening of earthquake intervals.

No frequent occurrence of large-magnitude earthquakes was detected immediately preceding the 2024 event (

Figure 3B) [

2]. The larger earthquakes were confined to the earlier swarm, and no anomalous seismic activity was observed directly before the mainshock. In fact, the swarm had subsided somewhat in the days leading up to the event—a trend even more pronounced in the 2007 case. The phenomenon of a particularly intense precursory swarm occurring immediately prior to the mainshock was not observed in any of the other earthquakes discussed below.

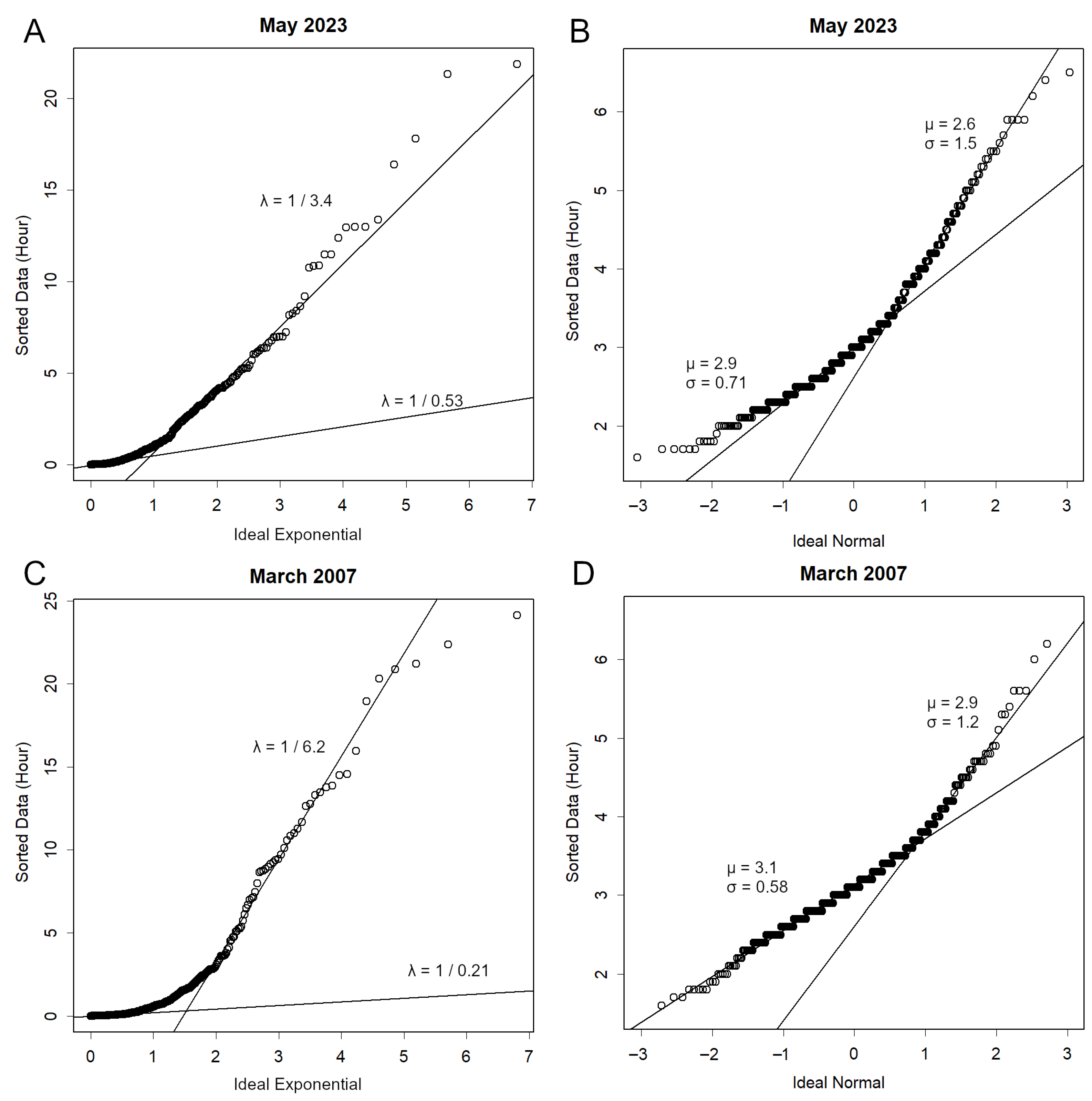

The shortening of earthquake intervals and increase in magnitude were difficult to detect when examining only the month preceding the event. In the absence of any special circumstances, the intervals between earthquakes follow an exponential distribution [

2]. This is a distribution known to represent the intervals between random events. Here, λ is the sole parameter of this distribution, with 1/λ corresponding to the mean interval and its scale. Indeed, such records were scarcely available in the periodical reports [

9]. However, when anomalies were identified during the swarm phase, the trends of decreasing intervals and increasing magnitudes became more evident (

Figure 3C,D and

Figure 4A,B). These precursors were also present prior to the 2007 Noto Peninsula earthquake (M6.9) (

Figure 3A,B).

3.2. The 2002 Northern Miyagi Earthquake (M6.4)

Several significant seismic events occurred around the same period, including the Miyagi-oki earthquake (M7.0) on 26 May 2003 and the Tokachi-oki earthquake (M8.0) in September 2003 [

9]. However, no records of precursory swarms were identified for these offshore events, possibly due to limitations in measurement capabilities. In July 2003, the Northern Miyagi earthquake (M6.4) occurred, but an increase in magnitude was only observed following the May Miyagi-oki event (M7.0) (

Figure S2).

3.3. The 2018 Eastern Iburi Earthquake (M6.7)

Documentation of the 2018 Eastern Iburi earthquake (M6.7), which struck Hokkaido, was limited in the periodical reports [

9]. This may be attributed to the sparse distribution of seismic intensity monitoring equipment in the region. The combined area of Ishikari, Iburi, and Urakawa comprises nearly 1% of Japan’s total landmass, yet seismic records from this region remain scarce. Analysis of the comprehensive catalogue data revealed a precursory swarm (

Figure 5A), with magnitudes within the swarm exceeding that of the mainshock (

Figure 5B).

Notably, the magnitude distribution in the catalogue does not conform to a normal distribution; instead, it exhibits a J-shaped curve. This suggests a potential underestimation of smaller earthquakes, likely due to detection limitations. Periodical data only include perceptible events, typically those with magnitudes greater than 2.

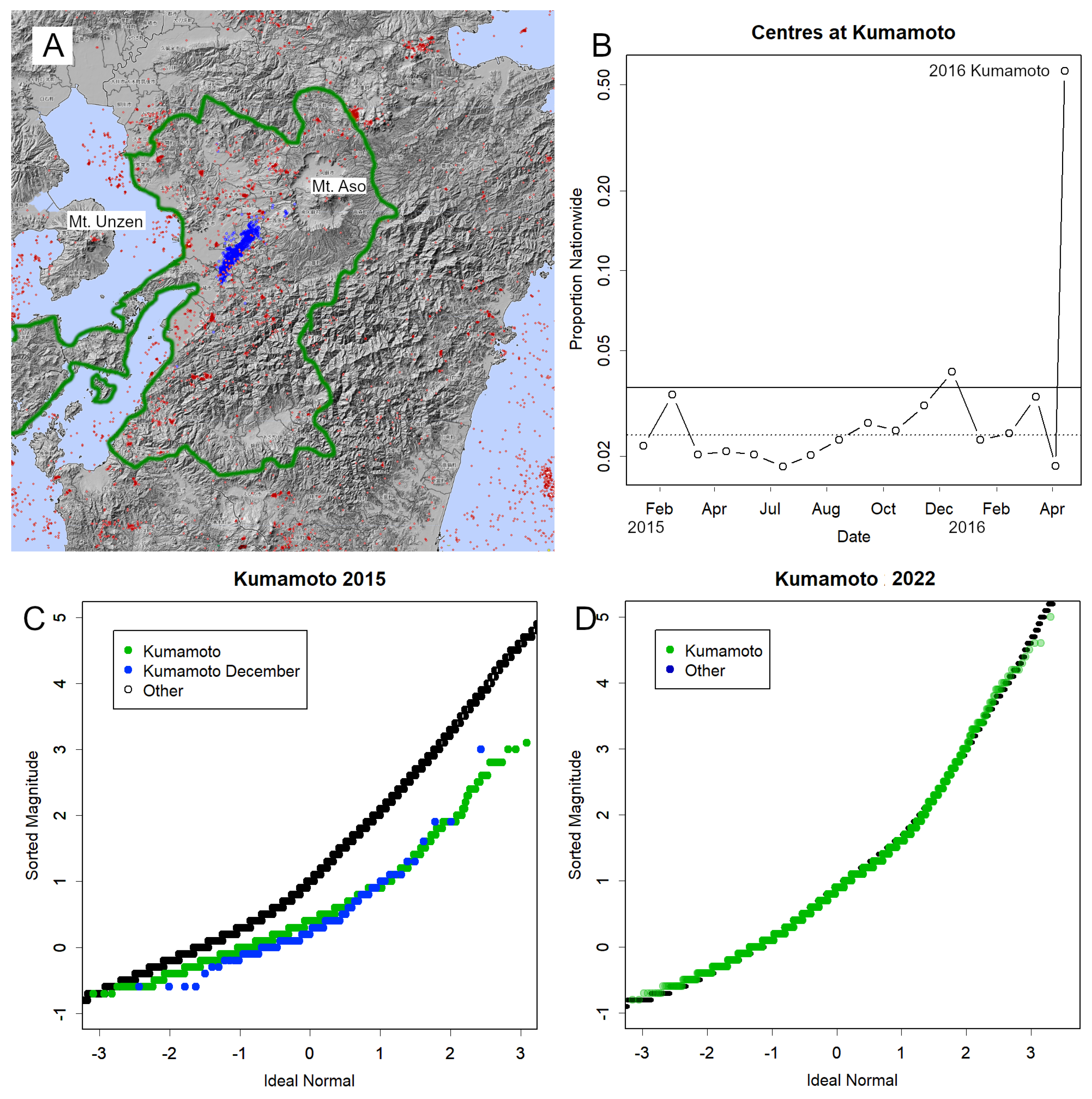

3.4. The 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake (M6.5)

There are instances where the location (μ) of magnitude, the mean, of a precursory swarm was reduced. One such case is the Kumamoto earthquake of April 2016 [

16,

17,

18]. Although considered a fault-driven event, the mainshock occurred on the flank of the active volcano Mount Aso (

Figure 6A, blue), and subsequent aftershocks reached the crater, culminating in an eruption.

The proportion of seismic activity in this region increased, briefly exceeding the 3σ threshold (

Figure 6B). However, both during the swarm phase (blue) and throughout the year (green), the magnitude μ and standard deviation σ remained consistently low (

Figure 6C). This trend is particularly evident in the catalogue data. As in other volcanic regions, frequent low-magnitude earthquakes likely result from magma movement. Unlike Tokara [

19], the epicentres observed in 2015 prior to the mainshock were dispersed across the entire prefecture (

Figure 6A, red), suggesting the presence of multiple magma pathways.

By 2022, these low-σ, low-μ anomalies had dissipated, and the region’s seismic characteristics had returned to background levels (

Figure 6D). This implies heightened volcanic activity during 2015 and 2016.

3.5. The 2000 Miyake Island Eruption (M5.6)

A comparable example of a low-σ precursory swarm is the earthquake (M5.6) associated with the Miyakejima eruption in June 2000 [

9]. In this case, a swarm occurred approximately one year prior (

Figure S3A). Analysis of the catalogue data from this period reveals magnitudes higher than the overall average, yet with a low σ (

Figure S3B , green). Throughout the year, magnitudes remained consistently elevated (blue), a pattern also confirmed in the periodical reports (

Figure S3C).

It is likely that frequent earthquakes on Miyakejima serve to supply magma to the active volcano. These events appear to exhibit low σ but high μ. However, this anomaly had resolved by 2022 (

Figure S3D), suggesting that the period of heightened seismic activity had concluded.

3.6. Volcanic Presence Does Not Necessarily Imply Lower σ Values

The presence of a volcano does not inherently result in a lower standard deviation (σ) of earthquake magnitudes. This was evident in Kumamoto in 2022 (

Figure 6D) [

17,

18] and Miyakejima in 2000 (

Figure S3C) [

9]. Similarly, in the Kagoshima prefecture—home to the active volcano Sakurajima—the recorded magnitudes were nearly identical to the national background level (

Figure S4A) [

9]. Despite Sakurajima erupting in 2022, this suggests that volcanic activity in the region may not be strongly associated with seismic anomalies. Although Mount Fuji remains a concern due to the long interval since its last eruption, as of 2022, it appears to exert no discernible influence on σ values (

Figure S4B) [

20].

3.7. March 2022 Fukushima Offshore Earthquake (M7.3)

In this case, a precursory swarm was difficult to identify (

Figure 7A). While its offshore location may have contributed to this, a more significant factor was likely the presence of aftershocks from three magnitude 6-class earthquakes that occurred between March and May 2021. Nevertheless, catalogue data indicated that throughout 2021, the average magnitude in this region was slightly elevated compared to other areas (

Figure 7B). Although a nationwide increase in magnitude was observed in December 2021, aggregated data for the Sanriku coast—including Fukushima—showed that magnitudes remained above background levels during this period (

Figure 7C). Further analysis revealed that a substantial portion of the December increase originated from this region (

Figure 7D).

3.8. The 2025 Tokara Islands Swarm Earthquakes

Swarm earthquakes have long been observed in the Tokara Islands [

21]. In periodicals that record only perceptible events, earthquakes in this region exhibit lower mean magnitudes (μ) and smaller σ values compared to other regions (

Figure S5A). However, catalogue data revealed the opposite trend, with μ values higher than the national average. This was true both in the frequently active zone between Akuseki and the Takara Islands (

Figure S5B) and in the intermittently active area near Suwanose Island (

Figure S5C).

Due to this discrepancy, published reports showed higher magnitudes near Suwanose Island, whereas catalogue data indicated otherwise (

Figure S5D). Typically, only a portion of the catalogue is published, and higher magnitudes tend to be concentrated in that subset, artificially inflating the μ value (compare panels A and B, or C and D, in black) [

9]. This trend is also evident in the Tokara data, although the magnitude of the increase appears to be smaller [

19].

3.9. Do Swarms Necessarily Precede Major Earthquakes?

In practice, regions with high detection rates—such as those shown in

Figure 3A—do tend to exhibit seismic activity both before and after major events. For example, the region with the highest frequency in 2021 was Fukushima, which experienced a magnitude 7.3 offshore earthquake in March. Noto ranked third, followed by Miyagi, each of which has experienced significant seismic events in recent years [

9].

However, in 2018—the year of the Eastern Iburi earthquake—Ishikari and Iburi ranked only 19th in terms of seismic frequency. The top regions by proportion were Ibaraki, Oshima, Shiga, and Kumamoto. Although these areas recorded high frequencies of seismic events, their magnitudes did not deviate significantly from background levels (

Figure S6A–C). The anomaly in Kumamoto (

Figure S6D), which showed a low μ in 2018 likely due to the 2016 earthquake, gradually diminished and had disappeared by 2022 (

Figure 6D).

In 2022, regions such as Fukushima, the Sanriku coast, and Noto exhibited relatively high values due to large aftershocks, but no anomalies were detected (

Figure S7A). The anomalies observed in previous years (

Figure 7) appear to have resolved. Subsequent regions included Wakayama and the Hyuga-nada area, yet no anomalies were found there either (

Figure S7B,C). Furthermore, the 2022 data for the Iburi region aligned with background levels (

Figure S7D), clearly contrasting with the elevated values seen in 2018 (

Figure 5B). Although data for Iburi remain limited, the evidence suggests that large earthquakes are not selectively recorded. Moreover, no significant seismic events have occurred in these regions since.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that even for earthquakes with energy approximately one-hundredth of that of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake—or smaller—identifying a precursory swarm and examining the associated magnitude distribution may offer insights into the likelihood of a forthcoming mainshock (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). However, no precursory swarm of the exceptionally large magnitude observed immediately prior to the Tohoku event was detected in these cases (

Figure 3B). Consequently, it remains challenging to pinpoint the precise timing of a mainshock, particularly given that a significant temporal gap—often up to six months—can exist between the swarm and the main event.

In several offshore seismic events, no precursory swarms were observed. This may be attributed to limitations in detection capabilities, as seismic instrumentation is not deployed in a uniform mesh across the region. Data acquisition is especially constrained over open ocean areas and in sparsely populated regions. In such cases, catalogue data may provide more comprehensive insights than periodical reports (

Figure 5). Moreover, even when a swarm was not clearly evident, analysis of magnitude distributions occasionally revealed anomalies (

Figure 7). It is important to note, however, that earthquakes cannot always be predicted. Some may occur suddenly, without warning. Furthermore, anomalies may persist as aftershocks continue. Determining whether the next major earthquake will strike immediately is difficult; continued vigilance is required.

Certain regions and time periods exhibited unusual magnitude distributions characterised by low standard deviation (σ), often accompanied by a lower mean magnitude (μ). These patterns were predominantly observed in volcanic regions such as Tokara (

Figure S5) [

18,

20], Mount Aso (

Figure 6), and Miyakejima (

Figure S3) [

9]. These events are likely attributable to magma-induced seismicity. As such earthquakes tend to occur under relatively stable conditions, their frequency is high and their σ values correspondingly low. In these volcanic zones, seismic activity appears to follow different statistical parameters compared to tectonic regions. Precursory swarms may not manifest in such contexts, possibly due to differing underlying mechanisms or their association with eruptive processes.

Although the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes are generally considered to be fault-driven [

18], the mainshock occurred on the flank of Mount Aso, and the subsequent aftershocks extended toward the crater, culminating in an eruption. This raises the question of whether the seismicity in this case should be re-evaluated in light of potential volcanic influences. Notably, the associated anomaly dissipated over the following years (

Figure 6D and

Figure S3D).

It is important to note that such low-σ phenomena do not occur uniformly across all volcanic regions. For instance, although Sakurajima in the Kagoshima prefecture erupted in 2022, no corresponding decrease in σ was observed (

Figure S4A). This may reflect the structural characteristics of Sakurajima, where magma movement is less likely to induce seismic activity. Indeed, the number of detected earthquakes in this region was relatively low—only about one-seventh of that recorded in the similarly sized Kumamoto region in 2022 [

9].

Conversely, swarm activity has persisted in the Tokara Islands (

Figure S5) [

18,

20]. While both σ and μ remain low, the possibility of significant earthquakes occurring without clear precursors in volcanic regions suggests that such areas may not be inherently safe. The ongoing evolution of seismic and volcanic activity in Tokara warrants close observation. Interestingly, the magnitude distributions in this region showed minimal discrepancy between periodicals and catalogue data, a pattern not commonly observed elsewhere. Typically, periodicals report only larger events, whereas catalogues include a broader range. If the catalogue data are accurate, the relatively higher magnitudes observed in Tokara may indicate a greater seismic hazard than previously assumed. This challenges earlier conclusions that the region was safe based solely on periodical records [

19].

The detection of swarm activity is relatively straightforward and appears to be a valuable tool. Regions exhibiting elevated seismic frequency are likely experiencing increased tectonic or volcanic stress. However, assessing the magnitude distribution at such locations is essential for evaluating the associated risk. If the observed magnitudes align with background levels, the likelihood of a major event is low. For instance, in regions with frequent activity in 2018 and 2022, no significant earthquakes followed (

Figures S6 and S7).

Nevertheless, caution is warranted. As demonstrated by the 2016 Kumamoto case, both μ and σ can decrease, potentially signalling heightened volcanic activity (

Figure 5,

Figures S3 and S5). Such conditions may necessitate a different form of risk assessment and preparedness, distinct from that applied to tectonic swarm events.

The approach employed here relies on relatively simple measurements, which has the advantage of being broadly applicable. This stands in contrast to approaches that draw on diverse measurement materials and attempt to identify singular points in time that appear to coincide with major earthquakes [

5,

6,

7,

8]. While such approaches may hold promise, it remains challenging to determine in advance the precise location of a forthcoming event [

1]. Pursuing this methodology to its logical conclusion may well shed light on the mechanisms of earthquakes. Future research will be valuable in this regard. In addition, given the frequent occurrence of large earthquakes in Japan, it is not straightforward to assess whether such singular points are directly related to the underlying causes of a particular earthquake. The coexistence of multiple predictive perspectives is, of course, to be regarded as valuable. In particular, as suggested in the present analysis, earthquakes of magnitude 6–7 did not appear to exhibit the pronounced, immediate precursor swarms that preceded the Tohoku disaster. Thus, the timing of the mainshock remains uncertain. Should another method be able to provide further insight into this aspect, it would represent a useful complement.

Here I have used some maps provided by JMA [

13] (

Figure 1A and

Figure 5A). Many of the maps on the JMA’s webpage are rendered using Leaflet [

22]; I acknowledge this with respect for the reliability of the technology.

In this study, hypothesis testing has not been performed on various phenomena—for instance, anomalies in the data in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, or the skewness of the data in

Figure 4. The reason is straightforward: it was unnecessary. It is often misunderstood that hypothesis testing constitutes the primary purpose of statistics. However, even statistical experts have raised concerns about the excessive focus on testing [

23,

24]. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was developed in response to this situation, emphasising the visualisation of differences in data rather than the conduct of statistical tests [

25]. Repeated testing can also lead to issues with multiple testing [

26]. I believe tests should only be performed when necessary; here, such situations simply did not arise. This issue is entirely unrelated to the rigour of data analysis.