Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Geospatial Modelling in the Central Himalaya

Abstract

1. Introduction

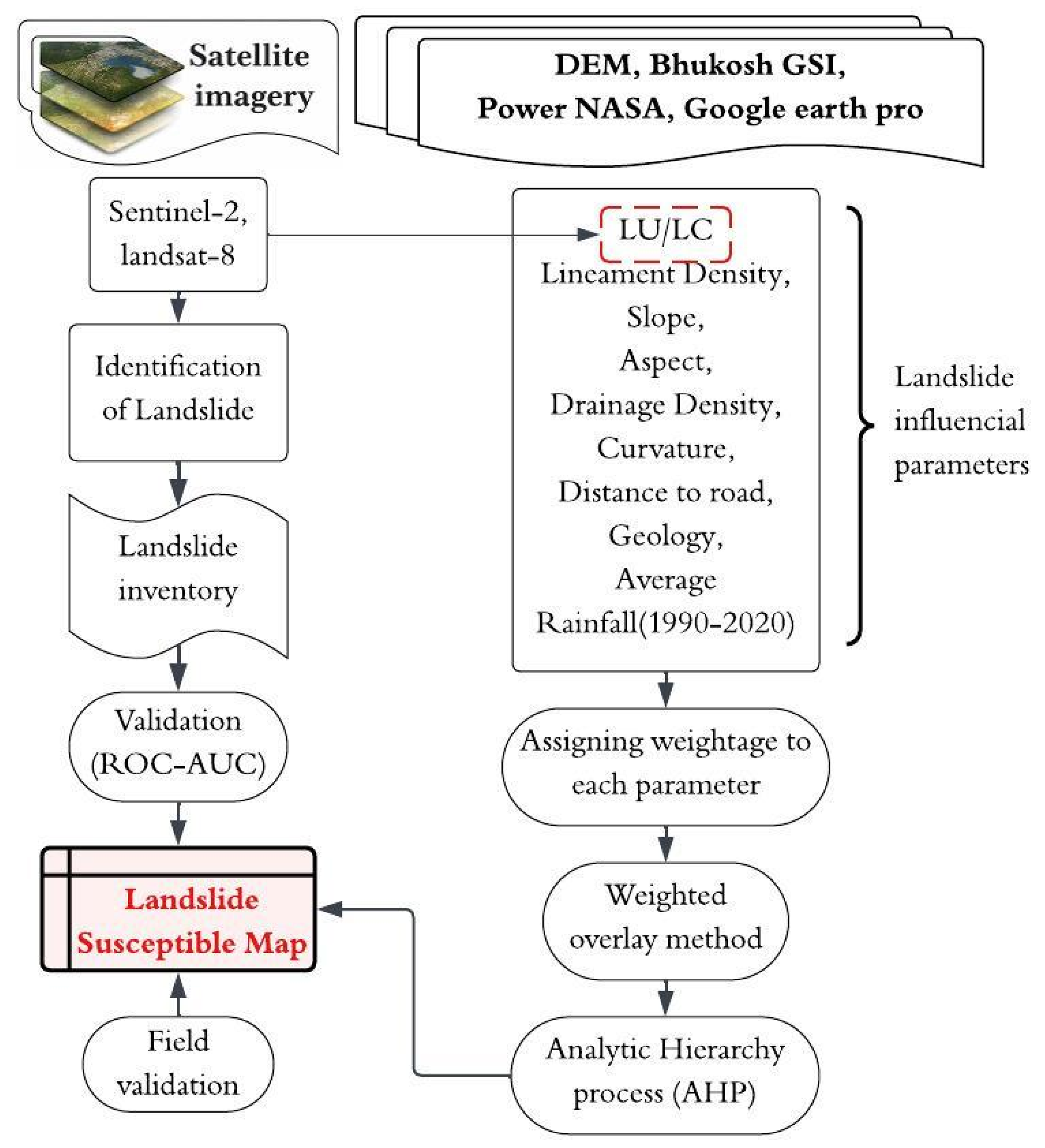

2. Data and Methods

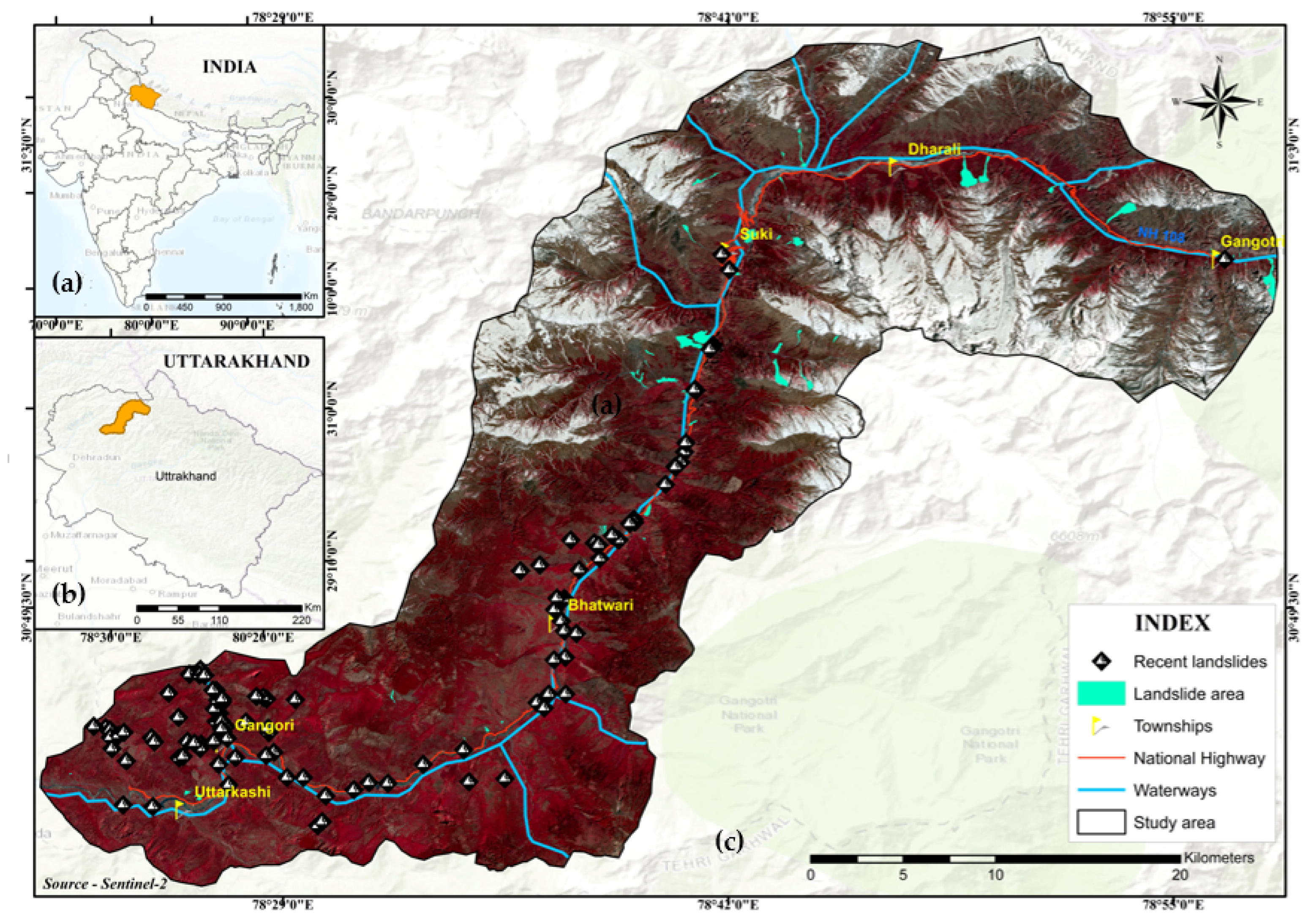

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Satellite Data and Thematic Layers

2.3. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

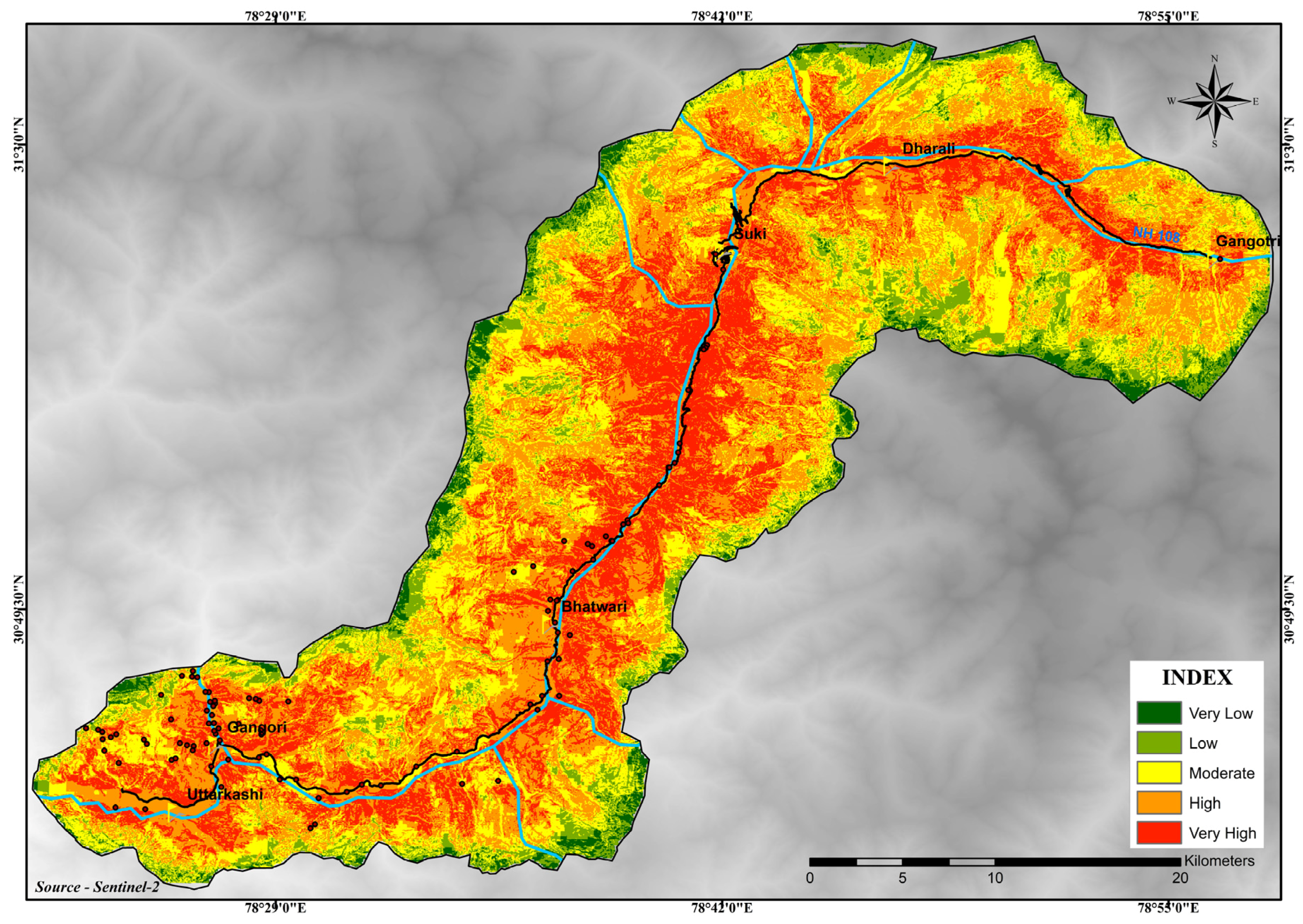

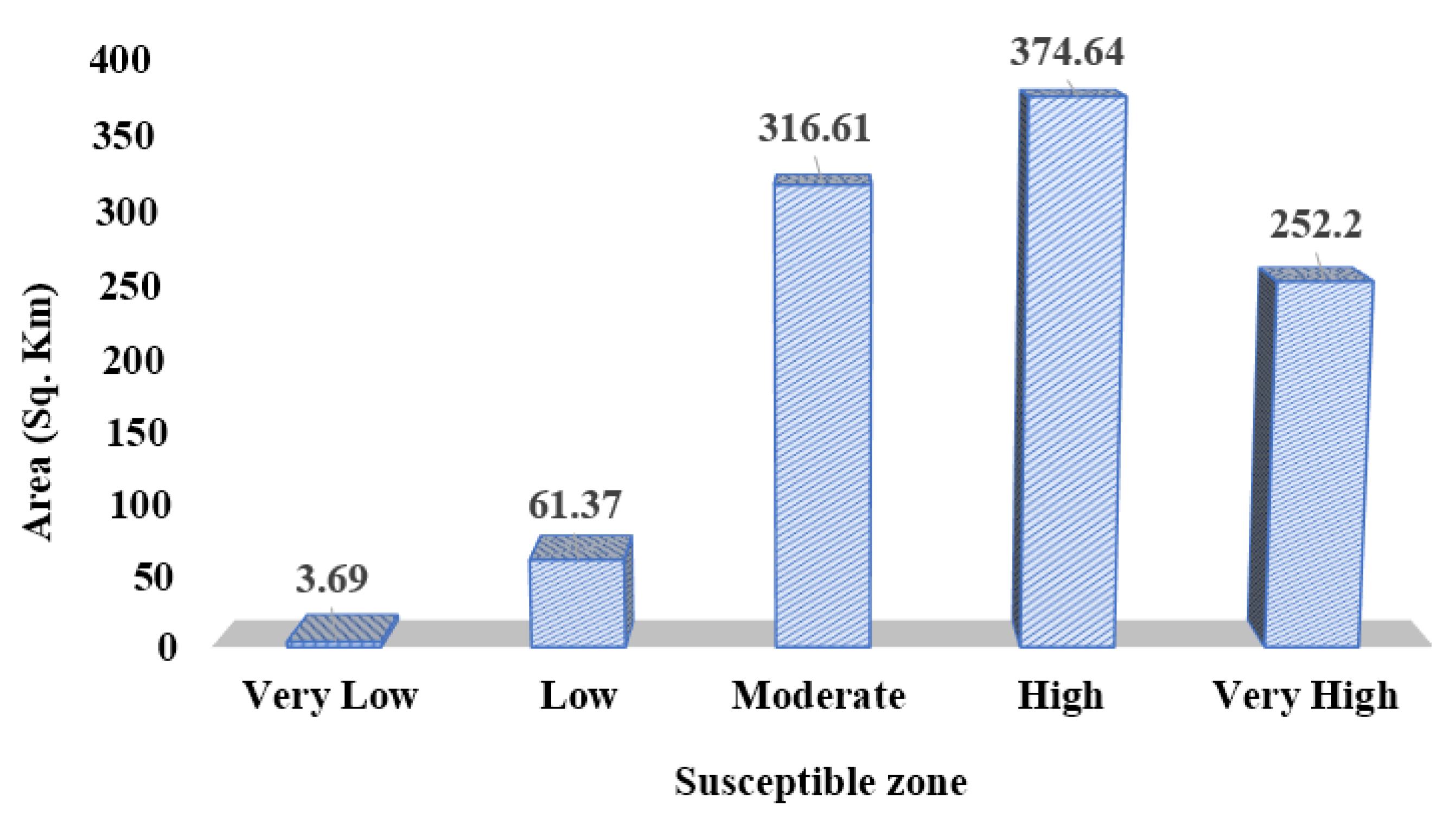

3. Results

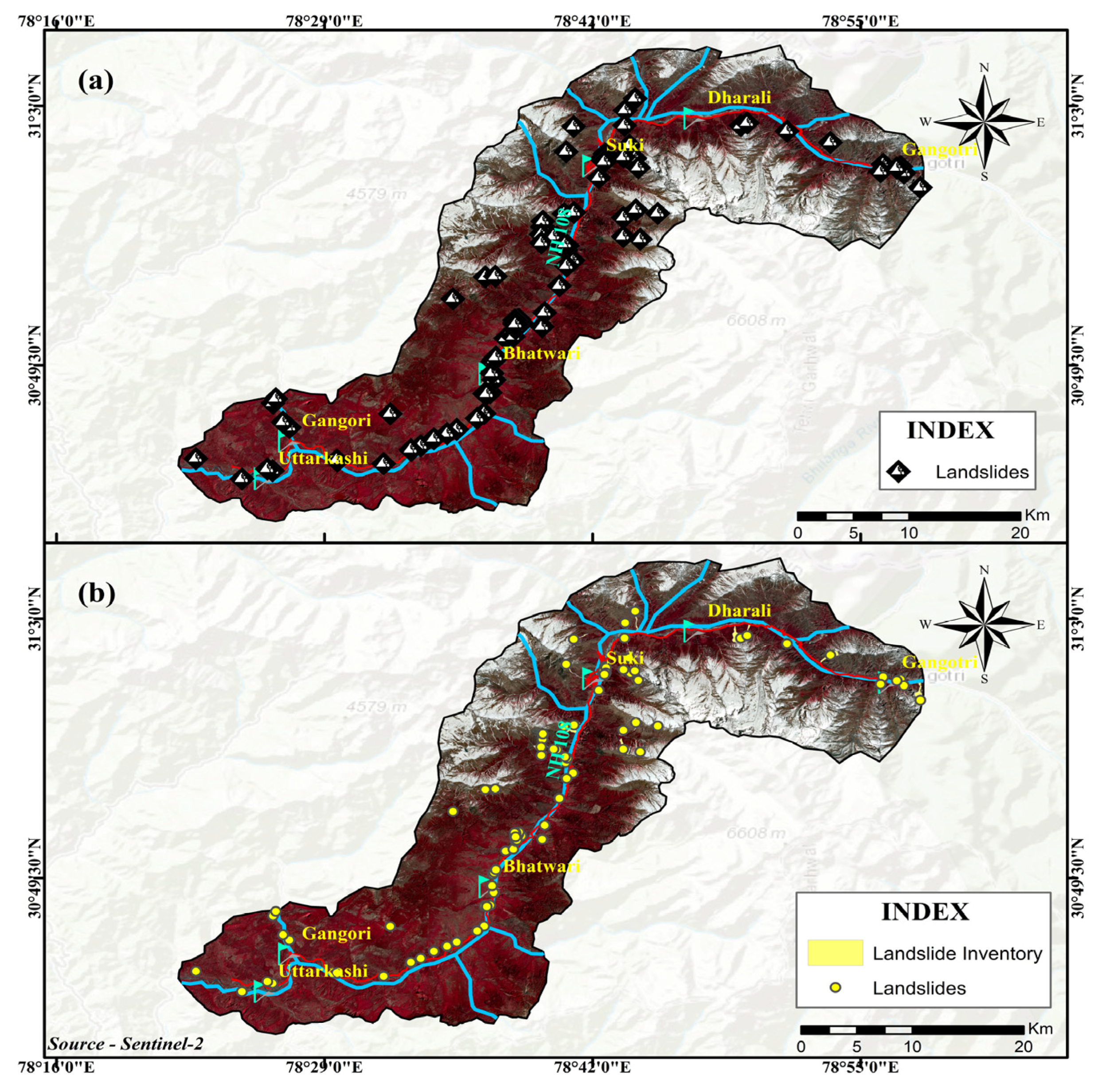

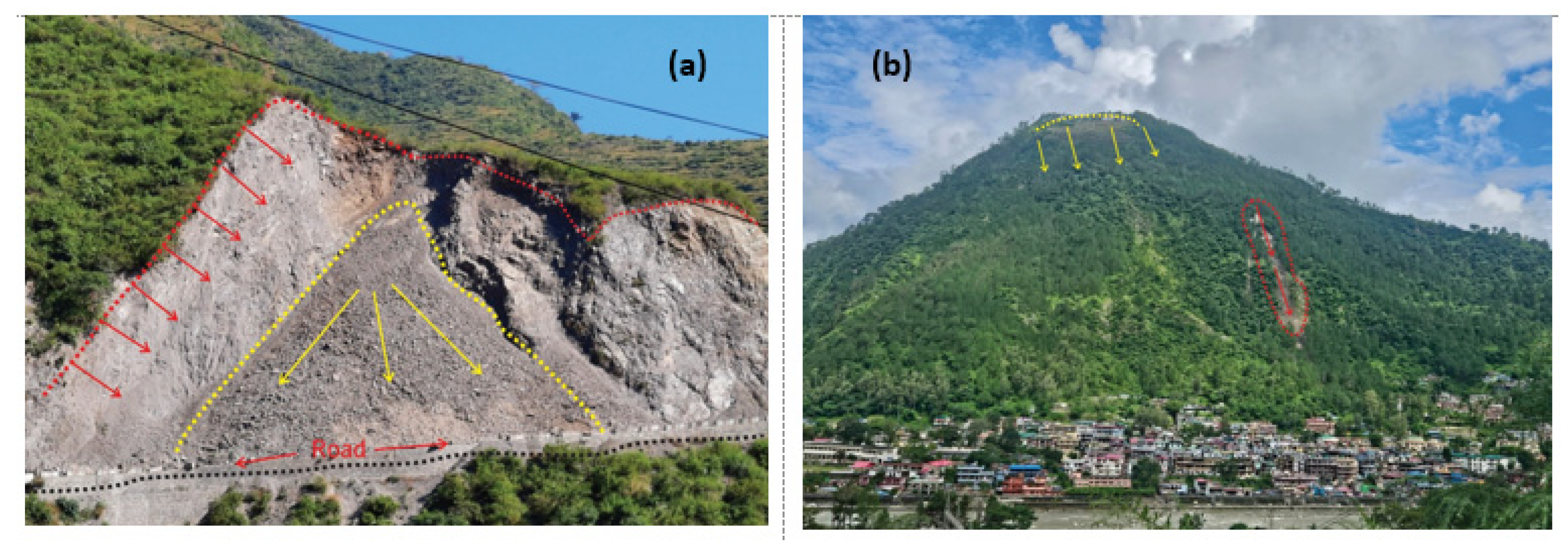

3.1. Landslide Inventories

3.2. Causative Factors

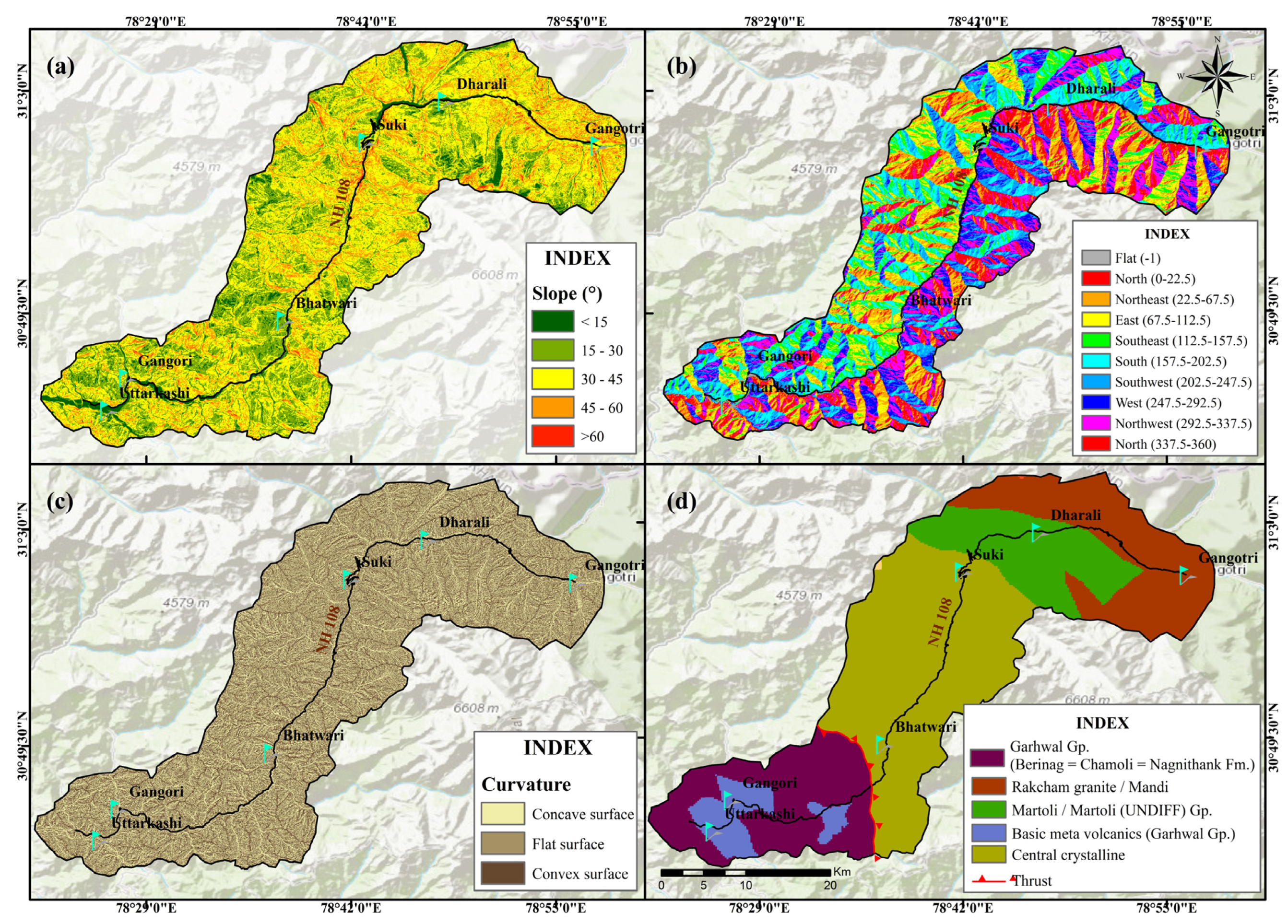

3.2.1. Slope, Aspect, Curvature and Geology

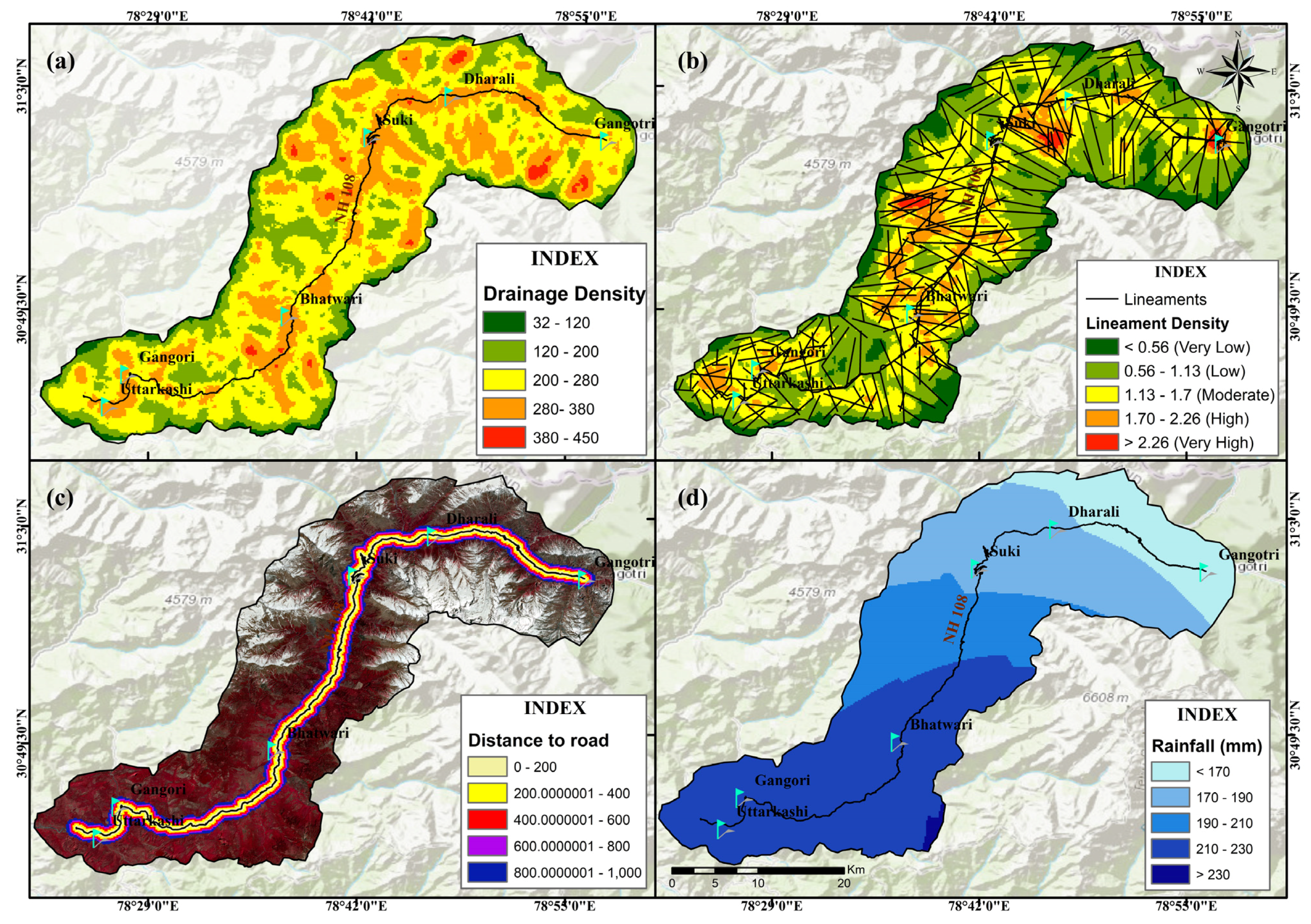

3.2.2. Drainage Density, Lineament Density, Distance-to-Road and Rainfall

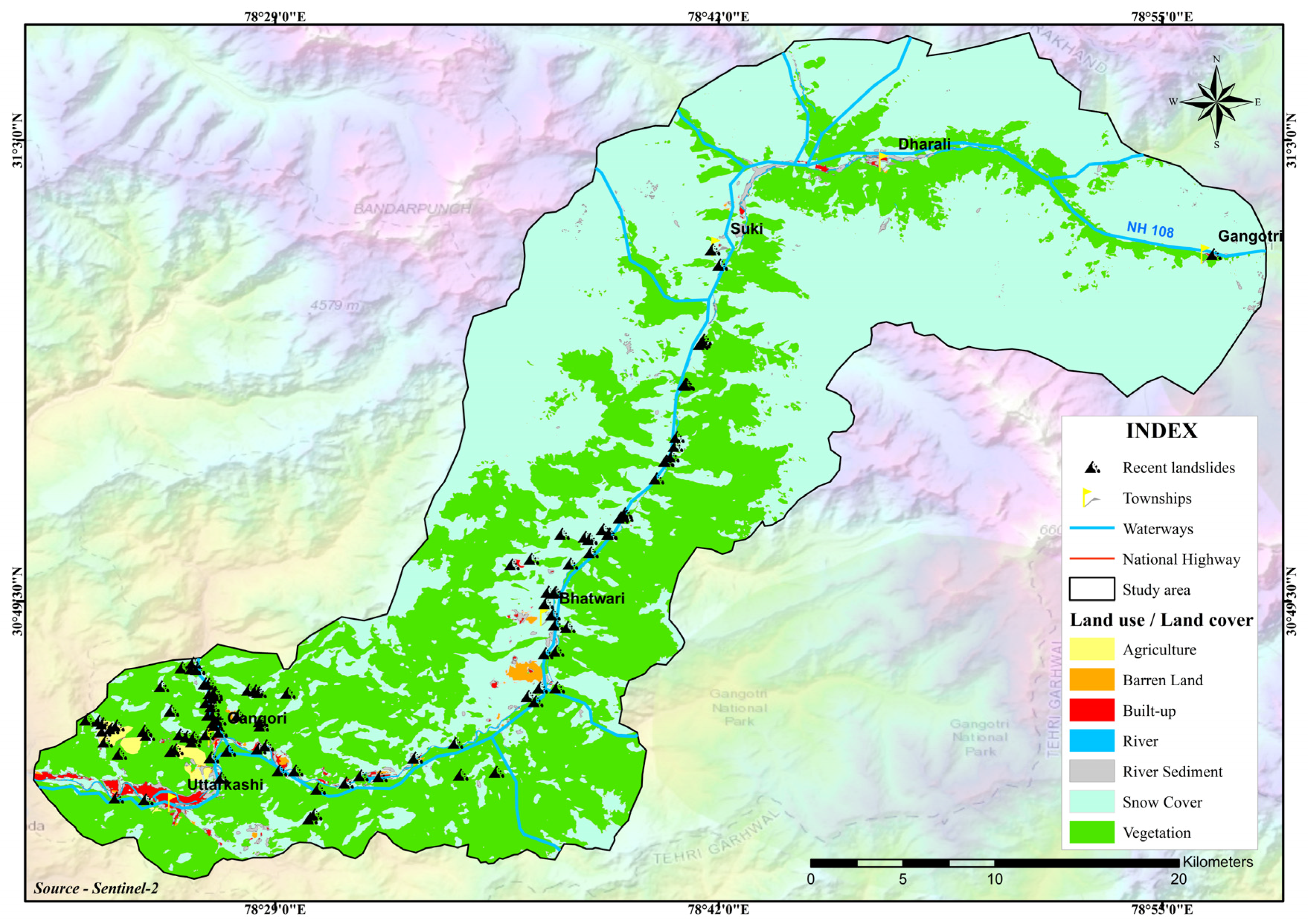

3.2.3. LULC

3.3. Pair-Wise Comparison Matrix and Weights of Thematic Layers for Landslide Susceptibility Analysis

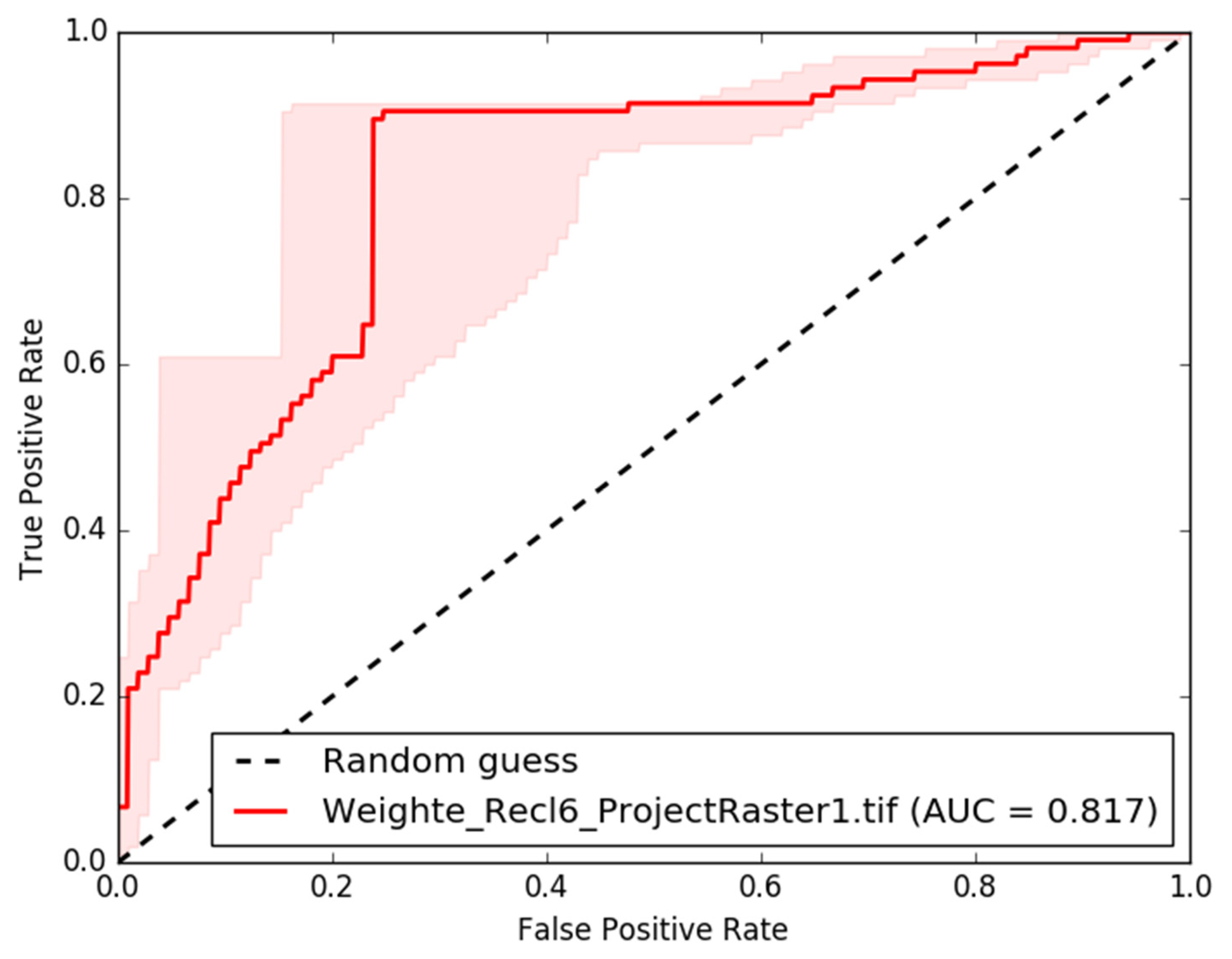

3.4. Validation

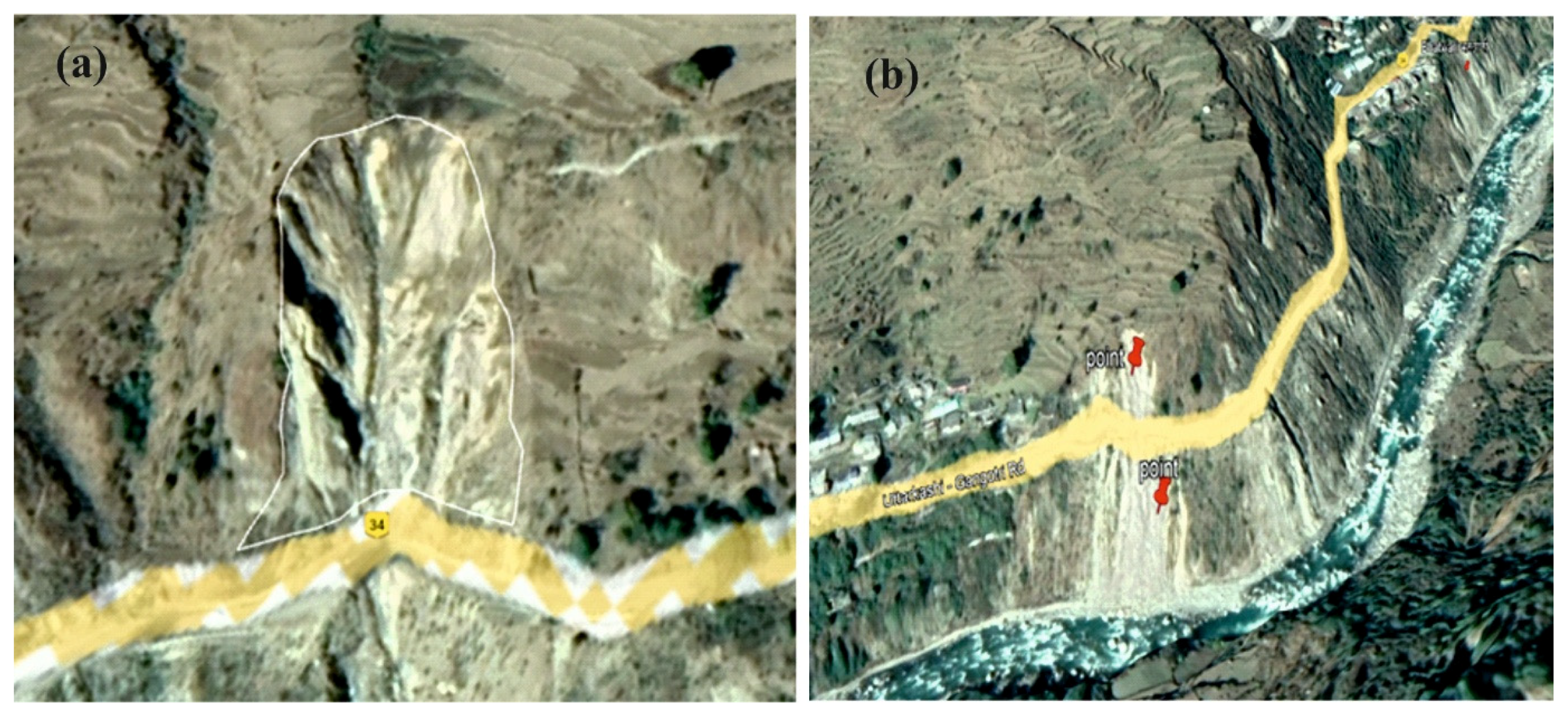

3.4.1. Field Validation

3.4.2. Validation of the Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shano, L.; Raghuvanshi, T.K.; Meten, M. Landslide Susceptibility Evaluation and Hazard Zonation Techniques—A Review. Geoenviron. Disasters 2020, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, B.; Behera, S.; Bakimchandra, O.; Pandey, A.; Singh, N. Evaluation of Satellite-Derived Rainfall Estimates for an Extreme Rainfall Event over Uttarakhand, Western Himalayas. Hydrology 2017, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, D.; Arabameri, A.; Santosh, M.; Egbueri, J.C.; Arora, A. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment and Mapping Using New Ensemble Model. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 2859–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikshit, A.; Sarkar, R.; Pradhan, B.; Segoni, S.; Alamri, A.M. Rainfall Induced Landslide Studies in Indian Himalayan Region: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Asthana, A.; Priyanka, R.S.; Jayangondaperumal, R.; Gupta, A.K.; Bhakuni, S. Assessment of Landslide Hazards Induced by Extreme Rainfall Event in Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya, Northwest India. Geomorphology 2017, 284, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, M.; Di Martire, D.; Bausilio, G.; Calcaterra, D.; Confuorto, P.; Firpo, M.; Pepe, G.; Cevasco, A. Rainfall-Induced Shallow Landslide Detachment, Transit and Runout Susceptibility Mapping by Integrating Machine Learning Techniques and GIS-Based Approaches. Water 2021, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Nie, R.; Zhang, W.; Fan, G.; Chen, C.; Ma, L.; Dai, X.; et al. Visualization Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Landslides Hazards Based on Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System-an Overview. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 2374–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, P.; Rossi, M.; Malamud, B.D.; Mihir, M.; Guzzetti, F. A Review of Statistically-Based Landslide Susceptibility Models. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 60–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Pourtaghi, Z.S.; Al-Katheeri, M.M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Random Forest, Boosted Regression Tree, Classification and Regression Tree, and General Linear Models and Comparison of Their Performance at Wadi Tayyah Basin, Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Landslides 2016, 13, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, A.C.; Guzzetti, F.; Chang, K.-T.; Monserrat, O.; Martha, T.R.; Manconi, A. Landslide Failures Detection and Mapping Using Synthetic Aperture Radar: Past, Present and Future. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 216, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zeng, T.; Wang, L.; Li, L. Advancing Seismic Landslide Susceptibility Modeling: A Comparative Evaluation of Deep Learning Models through Particle Swarm Optimization. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 3547–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, R.; Pandey, A.C.; Parida, B.R. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Monsoon Precipitation and Their Effect on Precipitation Triggered Landslides in Relation to Relief in Himalayas. Spat. Inf. Res. 2021, 29, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Alam, A.; Bhat, M.S.; Ahsan, S.; Ali, N.; Sheikh, H.A. Extreme Precipitation Events and Landslide Activity in the Kashmir Himalaya. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Khajuria, V.; Singh, S.; Singh, K. Landslide Susceptibility Evaluation in the Beas River Basin of North-Western Himalaya: A Geospatial Analysis Employing the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) Method. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2024, 14, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, A.K.; Nawani, P.C. Landslide Hazard Zonation Mapping of Tapovan—Helong Hydropower Project Area, Garhwal Himalaya, India, Using Univariate Statistical Analysis. J. Nepal Geol. Soc. 2009, 39, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Kanungo, D.P.; Chauhan, P.K.S. Varunavat Landslide Disaster in Uttarkashi, Garhwal Himalaya, India. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2011, 44, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.P.; Dubey, C.S.; Ningreichon, A.S.; Singh, R.P.; Mishra, B.K.; Singh, S.K. GIS-Based Morpho-Tectonic Studies of Alaknanda River Basin: A Precursor for Hazard Zonation. Nat. Hazards 2014, 71, 1433–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Pradhan, B.; Tien Bui, D.; Prakash, I.; Dholakia, M.B. A Comparative Study of Different Machine Learning Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Assessment: A Case Study of Uttarakhand Area (India). Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 84, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, A. GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Analytical Hierarchy Process and Bivariate Statistics in Ardesen (Turkey): Comparisons of Results and Confirmations. CATENA 2008, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, Y.; Hassani, H.; Maghsoudi, A. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using AHP and Fuzzy Methods in the Gilan Province, Iran. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 1797–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Pradhan, B.; Hong, H.; Bui, D.T.; Duan, Z.; Ma, J. A Comparative Study of Logistic Model Tree, Random Forest, and Classification and Regression Tree Models for Spatial Prediction of Landslide Susceptibility. Catena 2017, 151, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengstie, L.; Nebere, A.; Jothimani, M.; Taye, B. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment in Addi Arkay, Ethiopia Using GIS, Remote Sensing, and AHP. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2024, 15, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, C.S.; Dishant; Parida, B.R.; Pandey, A.C.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, N. Geoinformatics-Based Mapping of Environmental Sensitive Areas for Desertification over Satara and Sangli Districts of Maharashtra, India. GeoHazards 2024, 5, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, X.; He, X.; Qian, H.; Jiao, Q.; Gao, W.; Yang, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, P.; et al. Characteristics and Causes of the Landslide on July 23, 2019 in Shuicheng, Guizhou Province, China. Landslides 2020, 17, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jazouli, A.; Barakat, A.; Khellouk, R. GIS-Multicriteria Evaluation Using AHP for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping in Oum Er Rbia High Basin (Morocco). Geoenviron. Disasters 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Maiti, A.; Paul, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Paul, S. Mapping the Multi-Hazards Risk Index for Coastal Block of Sundarban, India Using AHP and Machine Learning Algorithms. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 2022, 11, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Li, Z.; Xu, Q.; Burgmann, R.; Milledge, D.G.; Tomas, R.; Fan, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Peng, J.; et al. Entering the Era of Earth Observation-Based Landslide Warning Systems: A Novel and Exciting Framework. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2020, 8, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-H.; Gao, Y.-C.; Jia, L.; Wang, W.-J.; Wu, Q.-B.; Zvomuya, F.; Dyck, M.; He, H.-L. Enhanced Detection of Freeze—Thaw Induced Landslides in Zhidoi County (Tibetan Plateau, China) with Google Earth Engine and Image Fusion. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 15, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangmene, F.L.; Ngapna, M.N.; Ateba, M.C.B.; Mboudou, G.M.M.; Defo, P.L.W.; Kouo, R.T.; Dongmo, A.K.; Owona, S. Landslide Susceptibility Zonation Using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in the Bafoussam-Dschang Region (West Cameroon). Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 5282–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Das, J.; Kanungo, D.P. Earthquake-Induced Landslide Hazard Assessment Using Ground Motion Parameters: A Case Study for Bhagirathi Valley, Uttarakhand, India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 134, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Nautiyal, H.; Kumar, V.; Jamir, I.; Tandon, R.S. Landslide Hazards around Uttarkashi Township, Garhwal Himalaya, after the Tragic Flash Flood in June 2013. Nat. Hazards 2016, 80, 1689–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Shukla, T.; Bhambri, R.; Gupta, A.K.; Dobhal, D.P. Terrain Changes, Caused by the 15–17 June 2013 Heavy Rainfall in the Garhwal Himalaya, India: A Case Study of Alaknanda and Mandakini Basins. Geomorphology 2017, 284, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Taloor, A.K.; Chandra Kothyari, G. Mapping of Major River Terraces and Assessment of Their Characteristics in Upper Pindar River Basin, Uttarakhand: A Geospatial Approach. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2021, 4, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallayu, P.T.; Singh, K.; Onyelowe, K.C.; Sharma, A.; Tiwary, A.K. Rainfall-Induced Landslides in Himachal Pradesh: A Review of Current Knowledge and Research Trends. Cogent Eng. 2025, 12, 2530569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, P.B.; Bhandari, B.P. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Frequency Ratio and Weight of Evidence Models in Purchaudi Municipality, Baitadi District, Nepal. Nepal J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, P.T.; Pramanik, S.; Ngoc, T.T.H. Soil Permeability of Sandy Loam and Clay Loam Soil in the Paddy Fields in An Giang Province in Vietnam. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineback Gritzner, M.; Marcus, W.A.; Aspinall, R.; Custer, S.G. Assessing Landslide Potential Using GIS, Soil Wetness Modeling and Topographic Attributes, Payette River, Idaho. Geomorphology 2001, 37, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Wolter, A. A Critical Review of Rock Slope Failure Mechanisms: The Importance of Structural Geology. J. Struct. Geol. 2015, 74, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mahajan, A.K. Comparative Evaluation of GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Statistical and Heuristic Approach for Dharamshala Region of Kangra Valley, India. Geoenviron. Disasters 2018, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sarkar, S.; Kanungo, D.P. GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Zonation Mapping Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Method in Parts of Kalimpong Region of Darjeeling Himalaya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill International: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kadavi, P.R.; Lee, C.-W.; Lee, S. Application of Ensemble-Based Machine Learning Models to Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayur Sadigh, A.; Alesheikh, A.A.; Bateni, S.M.; Jun, C.; Lee, S.; Nielson, J.R.; Panahi, M.; Rezaie, F. Comparison of Optimized Data-Driven Models for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 14665–14692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Saha, S. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Knowledge Driven Statistical Models in Darjeeling District, West Bengal, India. Geoenviron. Disasters 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K.; Gupta, R.P.; Sarkar, I.; Arora, M.K.; Csaplovics, E. An Approach for GIS-Based Statistical Landslide Susceptibility Zonation—With a Case Study in the Himalayas. Landslides 2005, 2, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Roy, J.; Pradhan, B.; Hembram, T.K. Hybrid Ensemble Machine Learning Approaches for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Different Sampling Ratios at East Sikkim Himalayan, India. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 2819–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuin, Y.; Otsuka, I.; Matsue, K.; Aruga, K.; Tasaka, T.; Hotta, N. Estimation of Shallow Landslides Caused by Heavy Rainfall Using Two Conceptual Models. Int. J. Eros. Control Eng. 2014, 7, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Bansal, V.K. Landslide Hazard Zonation Using Analytical Hierarchy Process Along National Highway-3 in Mid Himalayas of Himachal Pradesh, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikoo, M.W.; Rihan, M.; Ishtiaque, M.; Shahfahad. Analyses of Land Use Land Cover (LULC) Change and Built-up Expansion in the Suburb of a Metropolitan City: Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Delhi NCR Using Landsat Datasets. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Purpose | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | Slope, Aspect, Drainage density, Curvature | Shuttle Radar topography Mission (SRTM) Open Topography (https://opentopography.org/) |

| Sentinel-2B | Land use and land cover, Lineament Density | Copernicus (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/) |

| Geology, Geomorphology and Fault Line | Geology, Geomorphology, Main Central Thrust (MCT) | Bhukosh Geological Survey of India (GSI) (https://bhukosh.gsi.gov.in/Bhukosh/Public) |

| Landslide inventories | Visual demarcation of landslide inventories (Polygon), Visual Demarcation of landslide inventories (points) | Google Earth Pro (https://www.google.com/earth/versions/) |

| Rainfall data | Average Monthly rainfall of June to September (1990–2020) | Power NASA (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/) |

| Road line | Distance to road | Open Street Map (https://www.openstreetmap.org/) |

| Land Use/Land Cover | Area (km2) |

|---|---|

| River | 22.65 |

| Vegetation | 386.17 |

| Snow cover | 280.83 |

| Barren Land | 168.76 |

| River Sediment | 29.34 |

| Settlement | 84.79 |

| Agriculture | 46.67 |

| Parameters | Slope | Geology | Lineament density | Drainage density | Distance to road | Rainfall | Aspect | Curvature | LULC | Weight | Weight Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 0.23 | 23 |

| Geology | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 0.22 | 22 |

| Lineament density | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 0.21 | 21 |

| Drainage density | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.09 | 9 |

| Distance to road | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.08 | 8 |

| Rainfall | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.06 | 6 |

| Aspect | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.05 | 5 |

| Curvature | 0.111 | 0.167 | 0.167 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 0.03 | 3 |

| LULC | 0.111 | 0.125 | 0.111 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.02 | 2 |

| SUM | 4.506 | 4.575 | 4.561 | 10.083 | 13.083 | 16.833 | 22 | 32.5 | 42 | 1.00 | 100 |

| CR value | 0.0127 | ||||||||||

| Sl. No. | Thematic Parameters | Sub-Classes | Rank | Normalized Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Slope | Below 10 | 5 | 0.096 |

| 10–20 | 5 | 0.086 | ||

| 20–30 | 4 | 0.127 | ||

| 30–40 | 2 | 0.275 | ||

| 40–50 | 1 | 0.278 | ||

| Above 50 | 3 | 0.138 | ||

| 2 | Geology | Meta-Vocanics | 5 | 0.052 |

| Central Crystalline | 1 | 0.311 | ||

| The Garhwal group | 4 | 0.085 | ||

| The Martoli group | 2 | 0.290 | ||

| The Rakcham granite or Mandi | 3 | 0.263 | ||

| 3 | Lineament Density | Very Low | 5 | 0.072 |

| Low | 3 | 0.228 | ||

| Moderate | 1 | 0.243 | ||

| High | 2 | 0.228 | ||

| Very High | 4 | 0.228 | ||

| 4 | Drainage Density | Very Low | 5 | 0.093 |

| Low | 4 | 0.217 | ||

| Moderate | 3 | 0.217 | ||

| High | 1 | 0.236 | ||

| Very High | 2 | 0.236 | ||

| 5 | Distance to Road | 0–200 | 2 | 0.247 |

| 200–400 | 1 | 0.269 | ||

| 400–600 | 3 | 0.247 | ||

| 600–800 | 4 | 0.123 | ||

| 800–1000 | 5 | 0.114 | ||

| 6 | Rainfall | 157–170 | 5 | 0.103 |

| 171–190 | 4 | 0.111 | ||

| 191–210 | 1 | 0.284 | ||

| 211–230 | 2 | 0.262 | ||

| 231 & above | 3 | 0.241 | ||

| 7 | Aspect | Flat | 5 | 0.024 |

| North | 3 | 0.113 | ||

| North East | 4 | 0.088 | ||

| East | 4 | 0.068 | ||

| South East | 1 | 0.191 | ||

| South | 2 | 0.140 | ||

| South West | 1 | 0.213 | ||

| West | 5 | 0.047 | ||

| North West | 5 | 0.039 | ||

| North | 2 | 0.113 | ||

| 8 | Curvature | Concave | 2 | 0.416 |

| Flat | 3 | 0.126 | ||

| Convex | 1 | 0.458 | ||

| 9 | LULC | River | 4 | 0.105 |

| Vegetation | 1 | 0.222 | ||

| Snow cover | 3 | 0.129 | ||

| Barren Land | 1 | 0.222 | ||

| River Sediment | 5 | 0.077 | ||

| Settlement | 5 | 0.060 | ||

| Agriculture | 2 | 0.184 |

| Landslide Susceptible Zone | No. of Landslide Inventories |

|---|---|

| Very Low | 0 |

| Low | 1 |

| Moderate | 9 |

| High | 31 |

| Very High | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dwivedi, C.S.; Das, S.; Pandey, A.C.; Parida, B.R.; Swain, S.K.; Kumar, N. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Geospatial Modelling in the Central Himalaya. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010015

Dwivedi CS, Das S, Pandey AC, Parida BR, Swain SK, Kumar N. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Geospatial Modelling in the Central Himalaya. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleDwivedi, Chandra Shekhar, Suryaprava Das, Arvind Chandra Pandey, Bikash Ranjan Parida, Sagar Kumar Swain, and Navneet Kumar. 2026. "Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Geospatial Modelling in the Central Himalaya" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010015

APA StyleDwivedi, C. S., Das, S., Pandey, A. C., Parida, B. R., Swain, S. K., & Kumar, N. (2026). Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Geospatial Modelling in the Central Himalaya. GeoHazards, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010015