1. Introduction

Rice is a globally vital staple crop, with its yield and quality directly influencing food security, rural livelihoods, and socioeconomic stability [

1]. However, factors such as global warming, increased planting density, heavy fertilizer and pesticide use have led to the growing threat of rice pests. These pests, characterized by small size, high population density, severe leaf overlap, and complex backgrounds, are causing significant damage, reducing both yield and quality [

2]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for automated, intelligent, and lightweight pest detection technologies. These technologies can enable early warning, precise pesticide application, and eco-friendly pest control, ultimately advancing intelligent and sustainable agricultural production.

Traditional rice pest detection methods, such as manual field surveys, sex pheromone traps, and yellow sticky boards, are labour-intensive, depend heavily on the experience of field personnel, and may exhibit high omission rates under large-scale or dense-planting conditions. These methods fail to meet the demands of modern agriculture for “efficient, precise, and intelligent” pest monitoring in terms of time response, spatial coverage, and detection accuracy [

3,

4,

5,

6]. To address these limitations, computer-based pest detection methods have emerged. Traditional machine vision technology, through image acquisition, processing, and analysis, enables efficient, real-time pest identification and localization. This significantly enhances the automation and accuracy of monitoring, overcoming the shortcomings of conventional methods. Typical methods include pest discrimination systems based on classifiers such as Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors, Naive Bayes, Decision Trees, and Random Forests [

7,

8,

9,

10]. These methods typically rely on manually extracted low-level features like color, texture, and shape for pest image classification or localization. M.A. Ebrahimi et al. [

11] used the ratio of major to minor axes as a regional feature and hue, saturation, and intensity as color features, employing SVM with different kernel functions to detect potential parasites on strawberry plants. Limiao Deng et al. [

12] proposed a method based on integrating SIFT into the HMAX model and extracting invariant features using the LCP algorithm, achieving 85.5% recognition accuracy for pest identification in complex natural environments using SVM. However, such methods are highly sensitive to expert experience and relevant knowledge, involve cumbersome feature selection processes, and have limited generalization performance when facing complex field backgrounds, lighting variations, leaf occlusion, and multi-pest scenarios. These methods suffer from high false positives and missed detections, making them inadequate for practical production needs.

In recent years, deep learning has made significant progress in object detection tasks and has become a mainstream technology in agricultural vision. Among these, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series models, with their end-to-end structure and high inference speed, significantly improve pest detection accuracy and robustness, and have been widely applied in crop pest and disease identification. For example, Yunong Tian et al. [

13] proposed MD-YOLO, which enhances small object detection ability through a dense network and adaptive attention mechanism, specifically designed for small moth pests, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 86.2%. Yongkang Liu et al. [

14] introduced YOLO-Wheat, which improves the detection algorithm by using attention mechanisms and feature fusion, achieving an mAP of 89.6%. Yongzong Lu et al. [

15] developed MA-YOLO, a lightweight real-time detection model based on multi-scale convolution and dynamic weighting, with an mAP of 65.4% and 73.9% on the IP102 [

16] and Pest24 [

17] datasets, respectively. Sen Yang et al. [

18] proposed SRNet-YOLO, which addresses the issue of missed detections for low-resolution pests through super-resolution reconstruction and attention fusion, achieving an mAP of 78.2%, with an mAP of 57% even for very small pest targets. Nan Wang et al. [

19] proposed Insect-YOLO, which systematically extracts complex pest features and integrates multi-scale information to optimize feature representation. With only 8.2 GFLOPs of low computational demand, it enables fast and accurate identification of low-resolution pest images in the field. Despite recent advances, current lightweight YOLO based models remain insufficient for the complex pad field environment. First, its ability to extract spatial details of small targets is limited, resulting in missed detections. Second, modeling disturbances such as uneven lighting, occlusion, and image blur is challenging, leading to false positives. Third, despite the availability of lightweight versions, the model size and computational requirements remain incompatible with resource-constrained agricultural terminals or edge devices.

To overcome the aforementioned challenges and improve pest detection in paddy fields, the integration of global attention mechanisms, multi-scale feature optimization, and lightweight design is critical for addressing issues such as small target size, severe occlusion, and complex backgrounds. Beyond accuracy, the model’s robustness and minimal computational demand are vital for ensuring effective deployment on edge devices. In response, this study introduces GAFNet, an enhanced version of YOLO11n, incorporating strategies like global context fusion, efficient feature selection, lightweight detection heads, and an optimized loss function. These innovations enable precise and robust detection of rice pests, offering a highly efficient and sustainable solution for resource-constrained agricultural terminals and drone platforms.

The main contributions of this article include: proposing three novel modules that not only expand the receptive field, fuse attention, enhance channel selection, and strengthen features, but also make the model more lightweight; A new loss function has been proposed to maintain the training stability of bounding box regression for slender pests. Through a series of experiments and deployments, it has been proven that GAFNet not only has good generalization and robustness, but can also be deployed on convenient devices, providing a direct and practical method for precise pest management.

2. Methods

YOLO11 [

20], introduced by Ultralytics in 2024, signifies the next evolution in the YOLO series for real-time object detection. It achieves an optimal equilibrium between speed, precision, efficiency, and multi-tasking capabilities. YOLO11 is available in five configurations, n/s/m/l/x, with YOLO11n being the most lightweight in terms of parameter count and computational demand, making it particularly well-suited for rice pest detection in this paper. YOLO11n was chosen as the baseline model because it is extremely lightweight while maintaining accuracy, and also excellent in inference speed, making it very suitable for pest detection research on edge devices.

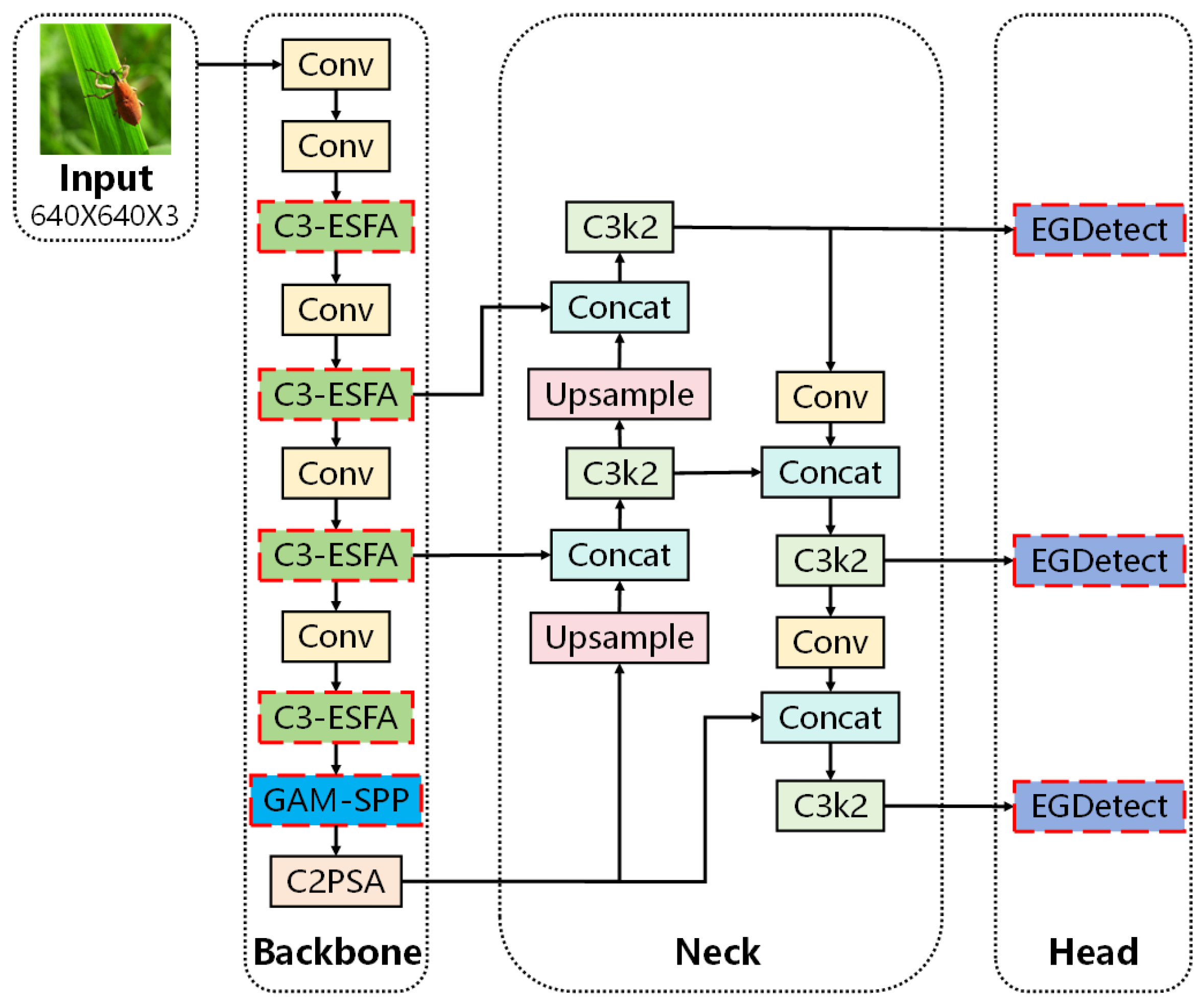

In the context of rice pest detection, YOLO11n encounters challenges such as minuscule object size, high density, severe occlusion, and intricate backgrounds. To address these challenges, we propose GAFNet, an enhanced variant of YOLO11n tailored for robust rice pest detection under field conditions. Initially, a novel Global Attention Fusion and Spatial Pyramid Pooling (GAM-SPP) module was introduced. This module integrates global contextual information from the rice field scene with multi-scale features to bolster the model’s ability to detect concealed pests. Subsequently, the C3 Efficient Feature Selection Attention (C3-EFSA) module is proposed, which merges depthwise separable convolutions (DWConv) [

21] with an Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) [

22], thereby enhancing feature discrimination efficiency in complex rice field environments. Furthermore, an Enhanced Ghost-based Detection Head (EGDetect) is introduced, which integrates Enhanced Ghost Convolution (EGConv), Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) [

23], and Sigmoid-Weighted Linear Unit (SiLU) [

24] to reformulate a lightweight composite structure, reducing computational redundancy. Finally, the Focal-Enhanced Complete-IoU (FECIoU) loss function, an advancement over Complete-IoU (CIoU) [

25], is presented, incorporating numerical stability terms and a hard sample weighting mechanism to further enhance pest localization under occlusion scenarios.

Through the synergistic design of these four components, GAFNet not only preserves the lightweight advantages of YOLO11n but also substantially enhances the accuracy, robustness, and adaptability to edge scenarios in rice pest detection. A schematic illustration of the rice pest detection mechanism based on the GAFNet model is presented in

Figure 1.

2.1. Multi-Scale Feature Enhancement Mechanism Based on Global Attention Fusion

In rice pest detection tasks, the targets often exhibit characteristics such as small size, high density, and severe occlusion, which result in significant loss of fine-grained spatial information during the feature extraction process, particularly in lightweight object detection models. While the original Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF) module in YOLO11n can expand the receptive field, it lacks the selective modeling ability for crucial target regions and salient channel information, limiting the model’s discriminative power for pest regions. To address this issue, this paper proposes a GAM-SPP module, which replaces the SPPF module in the YOLO11n model. The advantage of this module lies in its ability to retain multi-scale context fusion while integrating Channel Attention (CA) and Spatial Attention (SA), enabling more effective focus on the key information of rice pest regions.

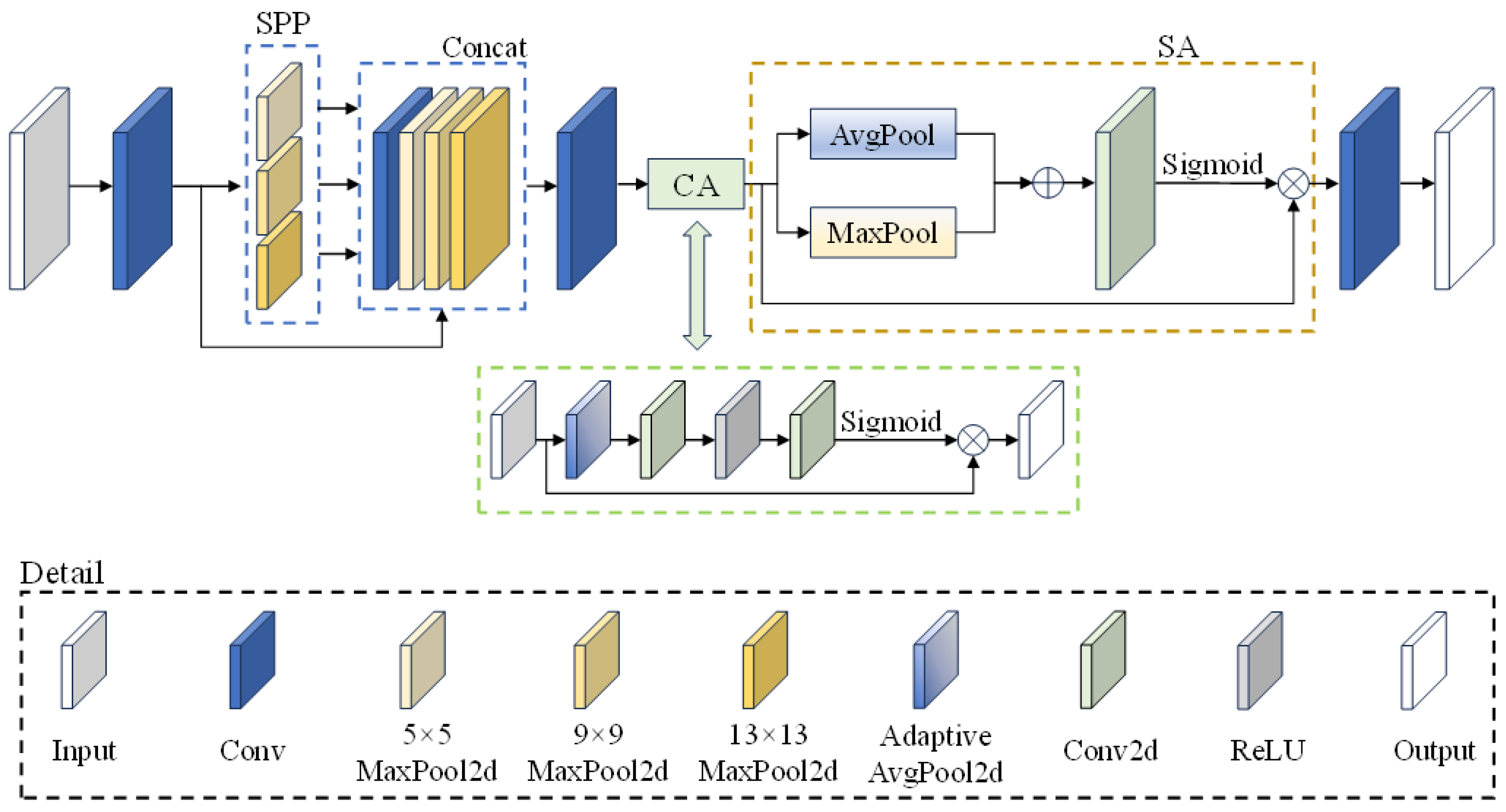

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed GAM-SPP module.

As depicted in

Figure 2, the GAM-SPP module proposed in this paper is primarily composed of the Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) [

26] branch, CA, and SA components. In the GAM-SPP module, the input feature map is first subjected to channel compression through a 1 × 1 convolution, followed by multi-scale pyramid pooling. Three distinct receptive field 2D max-pooling operations are sequentially introduced, utilizing kernel sizes of 5 × 5, 9 × 9, and 13 × 13, with a stride of 1 and appropriate padding to preserve the spatial dimensions of the feature map. This design effectively models multi-scale spatial contextual information, facilitating the detection of prominent regions within pest targets of varying sizes.

Next, feature fusion and channel compression are carried out. The original feature map is concatenated with the three pooled feature maps along the channel dimension, and a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to reduce the channel count back to the input size. This step prevents channel dimension expansion, reduces both parameters and computational overhead, and seamlessly integrates multi-scale semantic features.

The CA mechanism enables the model to dynamically adjust the importance of different channels, assigning greater attention to more relevant features. Utilizing the SE structure, CA performs global 2D adaptive average pooling on the fused features, followed by two 1 × 1 convolutions, each with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) [

27] and Sigmoid activations, respectively. The resulting channel-wise weight map is used to reweight the channel responses of the input features. Additionally, the SA mechanism models spatial saliency. SA is implemented by applying max-pooling and average-pooling along the channel dimension to generate two spatial maps. These maps are concatenated and processed through a 2D convolutional layer with a 7 × 7 kernel, followed by a Sigmoid activation to produce a spatial attention map. This map is used to reweight the feature map, allowing the model to focus more effectively on potential pest regions in rice leaves.

Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to further consolidate the feature map enhanced by the attention mechanism, ensuring that the output dimension matches the input size, thereby replacing the original SPPF module with the GAM-SPP.

2.2. Design of the C3-EFSA Module Based on Multi-Scale DWConv and Lightweight ECA Mechanism

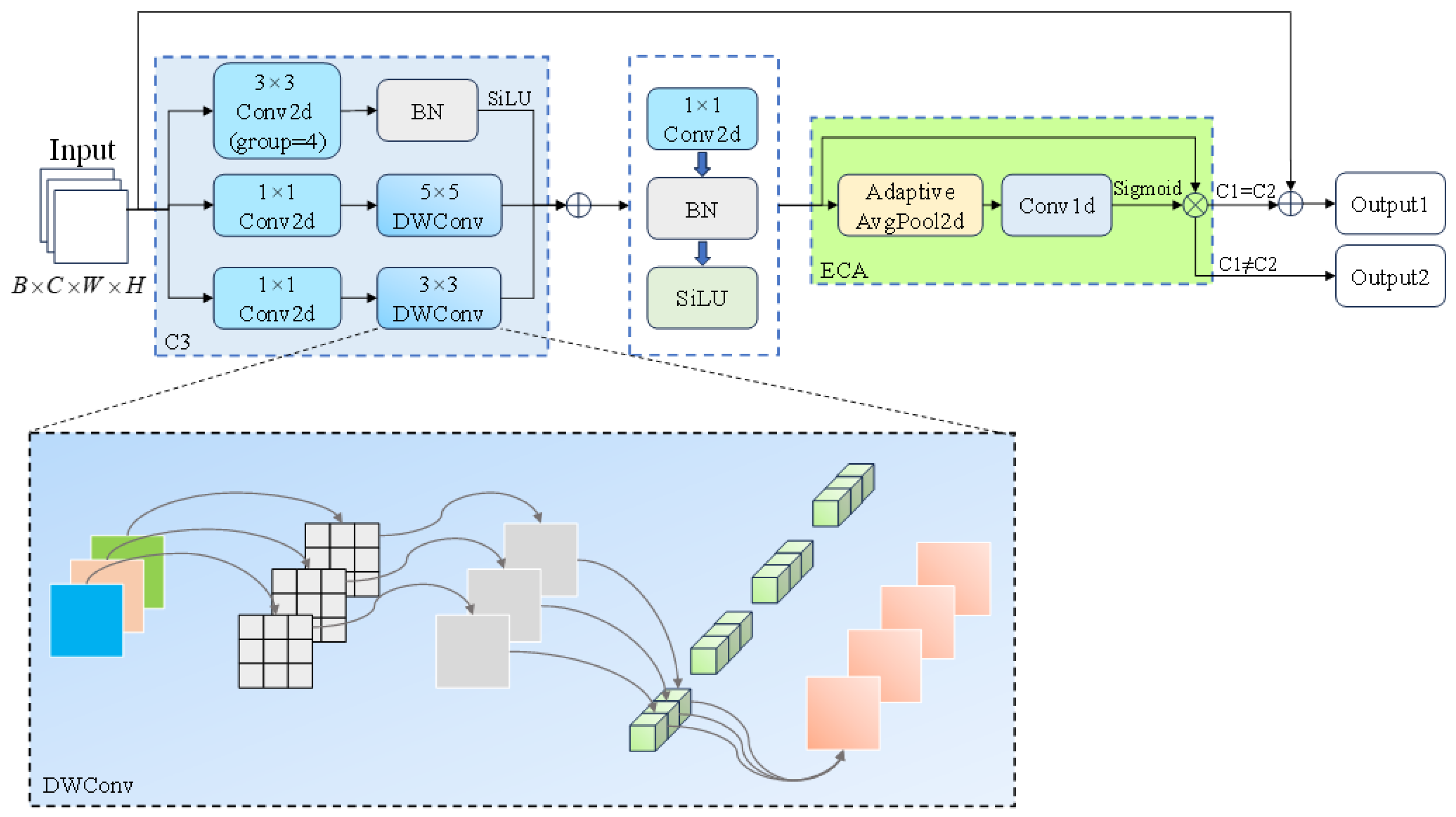

In the practical task of pest detection in rice fields, the feature extraction capability of the C3k2 module in YOLO11n exhibits certain limitations under various disturbances such as leaf occlusion and motion blur. To address this, a novel and more efficient module, C3-EFSA, is proposed in this paper, offering enhanced expressive power. C3-EFSA’s parallel depth-wise branches and ECA boost small-pest signal strength without extra cost, keeping accuracy under motion. By replacing all C3k2 modules in the backbone of the YOLO11n network with this module, the aim is to effectively reduce false negatives and false positives in complex environments, thereby improving the overall detection accuracy and robustness of the model. As shown in

Figure 3, this is a schematic representation of the proposed C3-EFSA module’s structural principles.

As shown in

Figure 3, the C3-EFSA module design incorporates lightweight multi-scale receptive field modeling and the ECA mechanism. This design aims to enhance the model’s ability to express pest features under limited computational resources. The core structure of the module adopts a three-branch parallel design, with each branch capturing structural information at different scales and spatial distributions from the input features. Among them, two branches employ 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 DWConv, preceded by a 1 × 1 convolution, to extract local and contextual texture information while balancing accuracy and computational efficiency. The third branch uses a 3 × 3 grouped convolution, which introduces cross-channel interactions while reducing computational overhead, followed by Batch Normalization (BN) [

28] and SiLU activation functions to enhance non-linear expressiveness. After concatenating the three feature maps along the channel dimension, they are fused using a 1 × 1 convolution. Then, BN and SiLU activation are applied to enhance non-linear representational capacity.

After the fusion of the three feature maps, the C3-EFSA module incorporates the ECA mechanism. Unlike traditional attention mechanisms, such as SE and Convolutional Block Attention Module [

29], ECA utilizes a lightweight 1D convolution, avoiding channel dimension compression and fully connected operations. The attention module first performs global 2D adaptive average pooling on the fused feature map to obtain the global response vector for each channel. It then enables local channel interactions via a 1D convolution with a small kernel, typically size 3. Finally, the Sigmoid activation function generates attention coefficients for each channel, which are applied to recalibrate the original feature map through weighted adjustments. As a result, the C3-EFSA module, augmented with ECA, significantly enhances the model’s focus on key regions of rice pest infestations. At the same time, it suppresses irrelevant background areas, improving the model’s ability to distinguish small rice pest targets.

Additionally, the C3-EFSA module preserves the residual connection structure [

30], where the module output is element-wise added to the input when the number of input and output channels are equal. This retains low-level feature information and facilitates stable gradient propagation in deep networks. This design further enhances the convergence speed during training and improves the overall stability of the network.

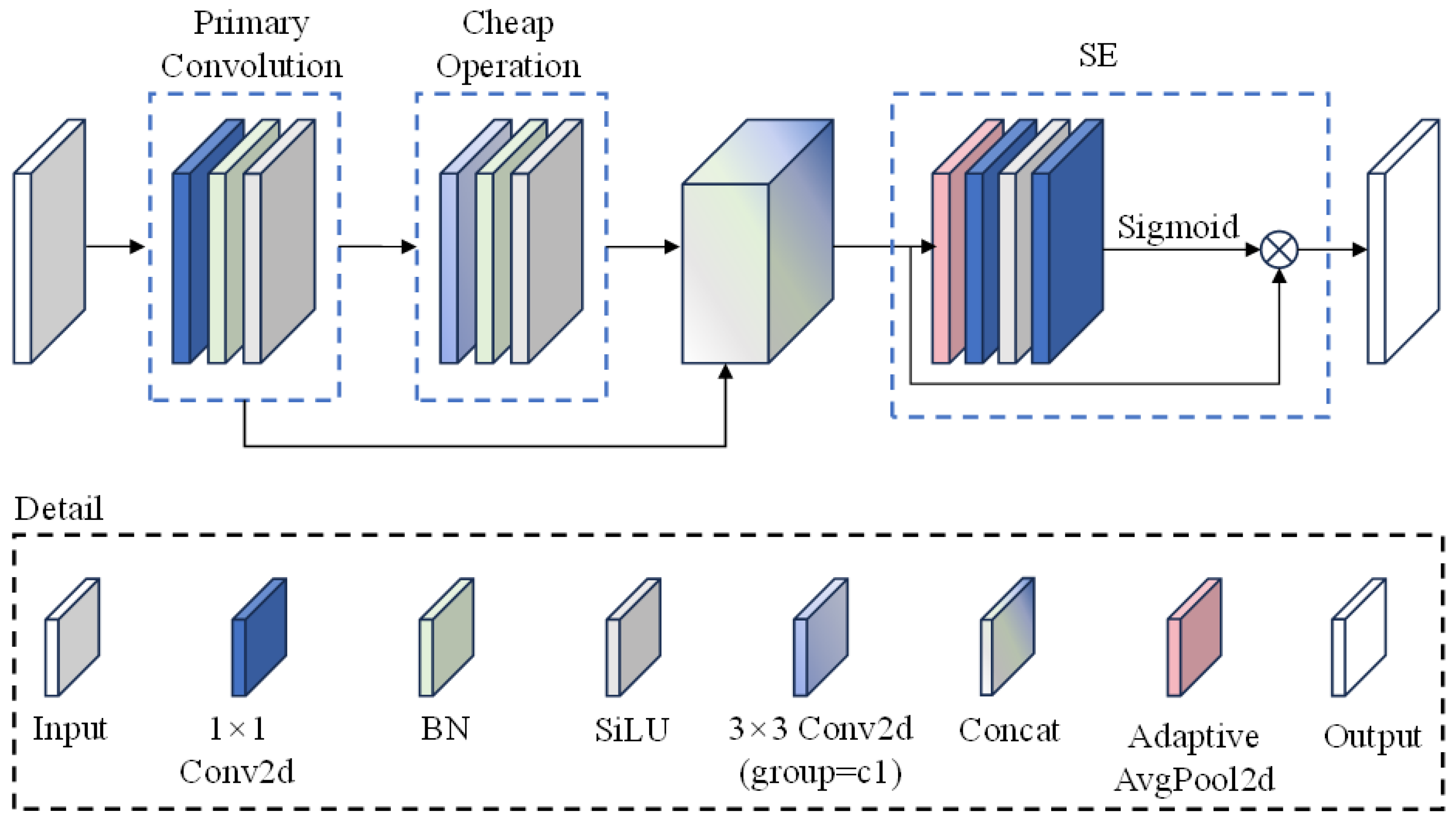

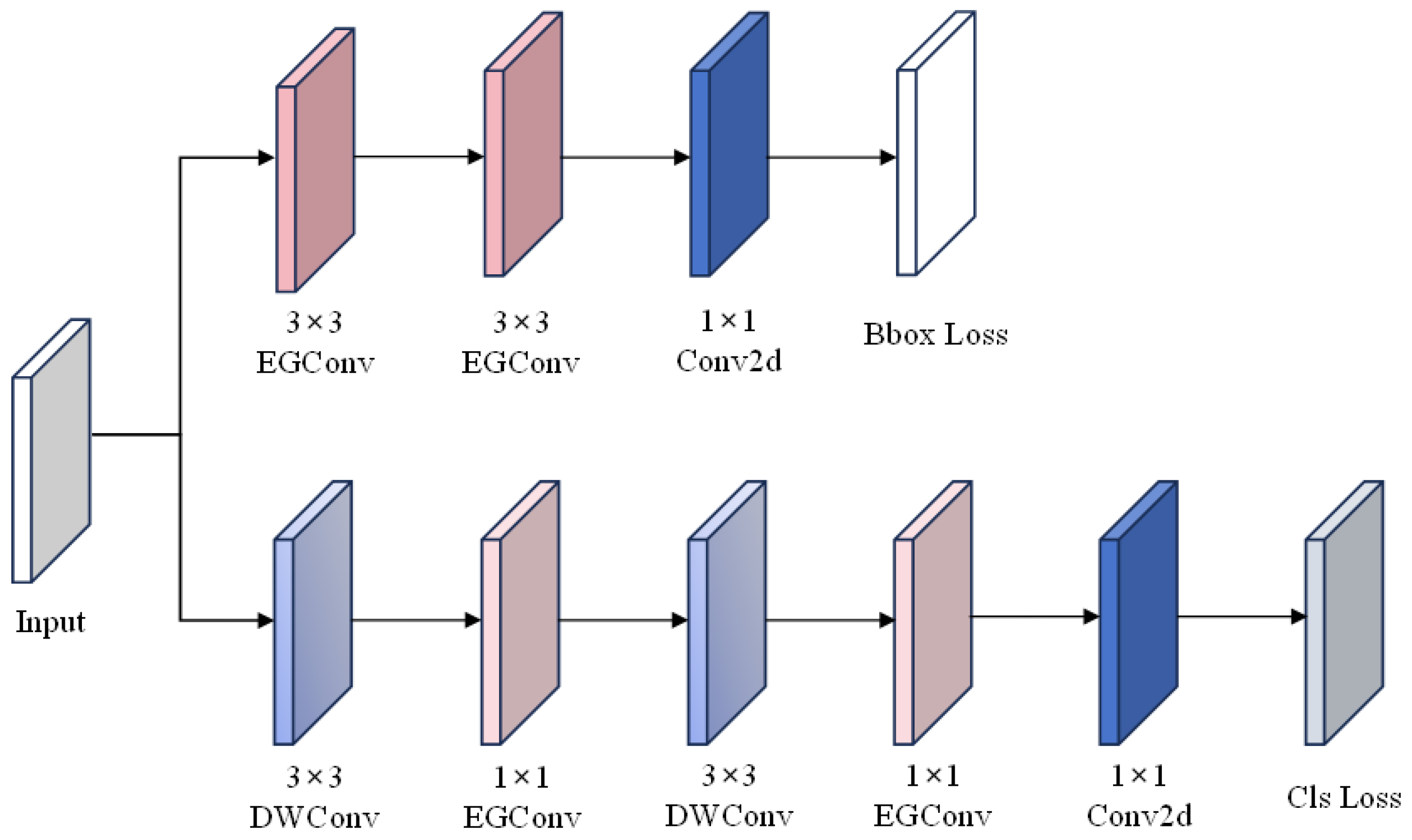

2.3. Lightweight Ghost Convolution Optimization Module with SE Attention Integration

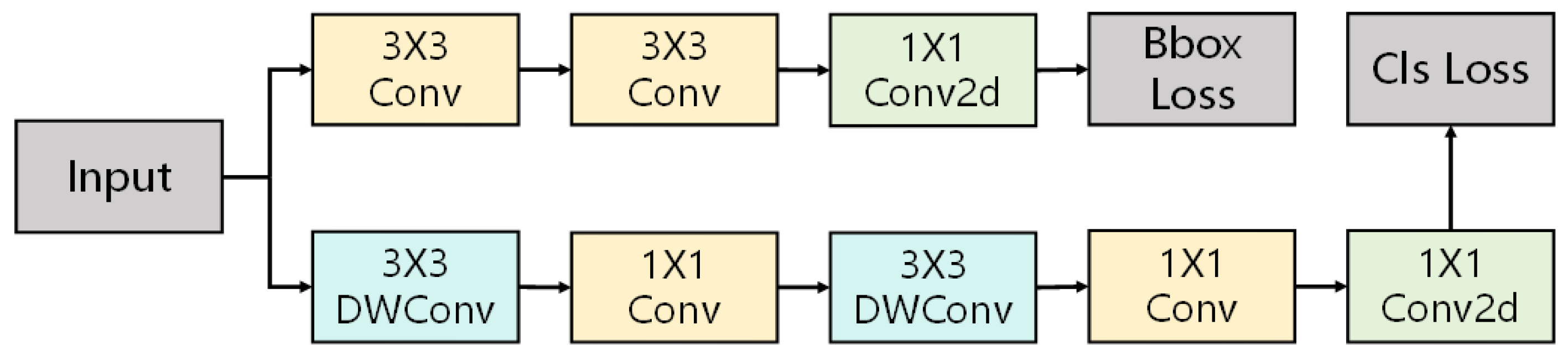

To enhance the model’s robustness in complex rice field scenarios, this paper optimizes the original Detect structure of YOLO11n. It introduces the EGDetect module to achieve this improvement. This module preserves the network’s lightweight nature while incorporating structural enhancements and attention mechanisms. As a result, it improves feature representation and enhances the model’s ability to focus on targets for rice pest detection.

As shown in

Figure 4, the original Detect module of YOLO11n consists of multiple standard convolution layers for bounding box regression and object classification. However, standard convolutions exhibit high feature redundancy and limited expressiveness, particularly when dealing with small or low-contrast targets. To reduce feature redundancy and enhance the focus on key target regions, this paper proposes a novel EGConv module based on Ghost Convolution [

31], which replaces the 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 standard convolutions in the original YOLO11n architecture.

Figure 5 illustrates the conceptual structure of the proposed EGConv module.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the core concept of EGConv is to generate core features through a subset of “real” convolutions (Primary Convolution), while the remaining features are “synthetically” generated from existing ones using computationally efficient operations (Cheap Operation), specifically DWConv. This approach significantly reduces computational costs. Specifically, EGConv first applies a standard convolution for initial feature extraction, where the number of output channels in the main branch contributes to a portion of the final output. These features are then passed through a DWConv to generate the remaining output channels, enabling richer feature representations. The outputs from both the primary and cheap branches are subsequently concatenated along the channel dimension to form the complete output.

To further enhance the model’s focus on key target regions, this paper introduces a lightweight channel attention mechanism, the SE module, into the EGConv module. The SE module extracts the response statistics of each channel through global 2D adaptive average pooling of the feature map. It then generates channel weights via two 1 × 1 2D convolutions to recalibrate the importance of each channel in the feature map. This mechanism effectively amplifies significant features related to pest targets while suppressing background noise and irrelevant regions. The attention output is applied to all concatenated channel features. A truncation operation ensures the final output’s channel count aligns with expectations, maintaining full compatibility with the original Detect module.

Furthermore, to enhance the network’s nonlinear expressive capability, this paper uniformly replaces all ReLU activation functions used in the EGConv module with the SiLU activation function. The SiLU activation function is defined as shown in Equation (1):

where

denotes each element of the input feature map and

represents the Sigmoid activation function, the SiLU activation function offers superior gradient continuity and expressive capability compared to the traditional ReLU. Particularly in tasks such as object regression and small object detection, it leads to more stable performance. The advantage of replacing the activation function lies in its ability to enhance optimization convergence and improve accuracy without altering the network’s structural dimensions.

In this paper, all 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 standard convolution modules in the original YOLO11n Detect are replaced with the new EGConv module to enhance the model’s feature generation, attention fusion capabilities, and activation function optimization. The improved version of the Detect module is named EGDetect, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

2.4. Design of the Enhanced Loss Function FECIoU

In rice pest detection, standard Intersection over Union (IoU) [

32] and its variants, like CIoU, show strong geometric modeling in bounding box regression. However, they struggle with small, occluded, and irregularly shaped targets, often failing to achieve optimal localization accuracy in capturing pest morphology and handling overlaps. To address this, we improve the CIoU loss in the original YOLO11n model and propose FECIoU, an enhanced loss function optimized for complex pest detection. The traditional CIoU loss

is defined in Equation (2):

Here, represents the squared Euclidean distance between the centers of the predicted and ground truth boxes. denotes the squared diagonal length of the minimal enclosing box. The aspect ratio discrepancy is quantified by , where and are the width and height of the ground truth box, and and are those of the predicted box. The aspect ratio penalty is a dynamic weight. However, in rice pest detection, where targets can be extremely small or elongated, the ground truth box height may approach zero. In such cases, the value of becomes excessively large, leading to numerical instability or gradient explosion. This instability significantly impairs the training process, especially when handling extreme target shapes, degrading the model’s convergence.

To address this issue, a small positive number

is introduced into the calculation, improving the aspect ratio discrepancy term

in CIoU, as shown in Equation (3):

In Equation (2), the weight term

may experience significant gradient fluctuations when the IoU is very small. To mitigate this issue and smooth gradient variations,

is redefined as shown in Equation (4):

In addition, to further enhance the model’s ability to fit samples, this paper introduces a difficult sample weighting mechanism similar to Focal Loss [

33] in the loss function. This mechanism utilizes a simple IoU index weighting term

to enhance the gradient influence of low-quality predictions, allowing the model to focus more on small targets, occluded or highly biased samples during training. Here,

is the focusing parameter that controls the intensity of this adjustment. In the experiment, in order to appropriately enhance the contribution of difficult samples without excessively disturbing normal sample training,

was set. Setting

to 0.05 yields a gentle yet non-zero increase in gradient for low-IoU samples, emphasizing hard cases without amplifying gradient noise or destabilizing optimization. This value aligns with the original Focal-Loss design principle, ensuring numerical stability while encouraging refinement of faint or partially occluded pests. Finally, the FECIoU loss function is expressed as Equation (5):

3. Experiments and Discussion

3.1. Dataset Preparation and Augmentation Methods

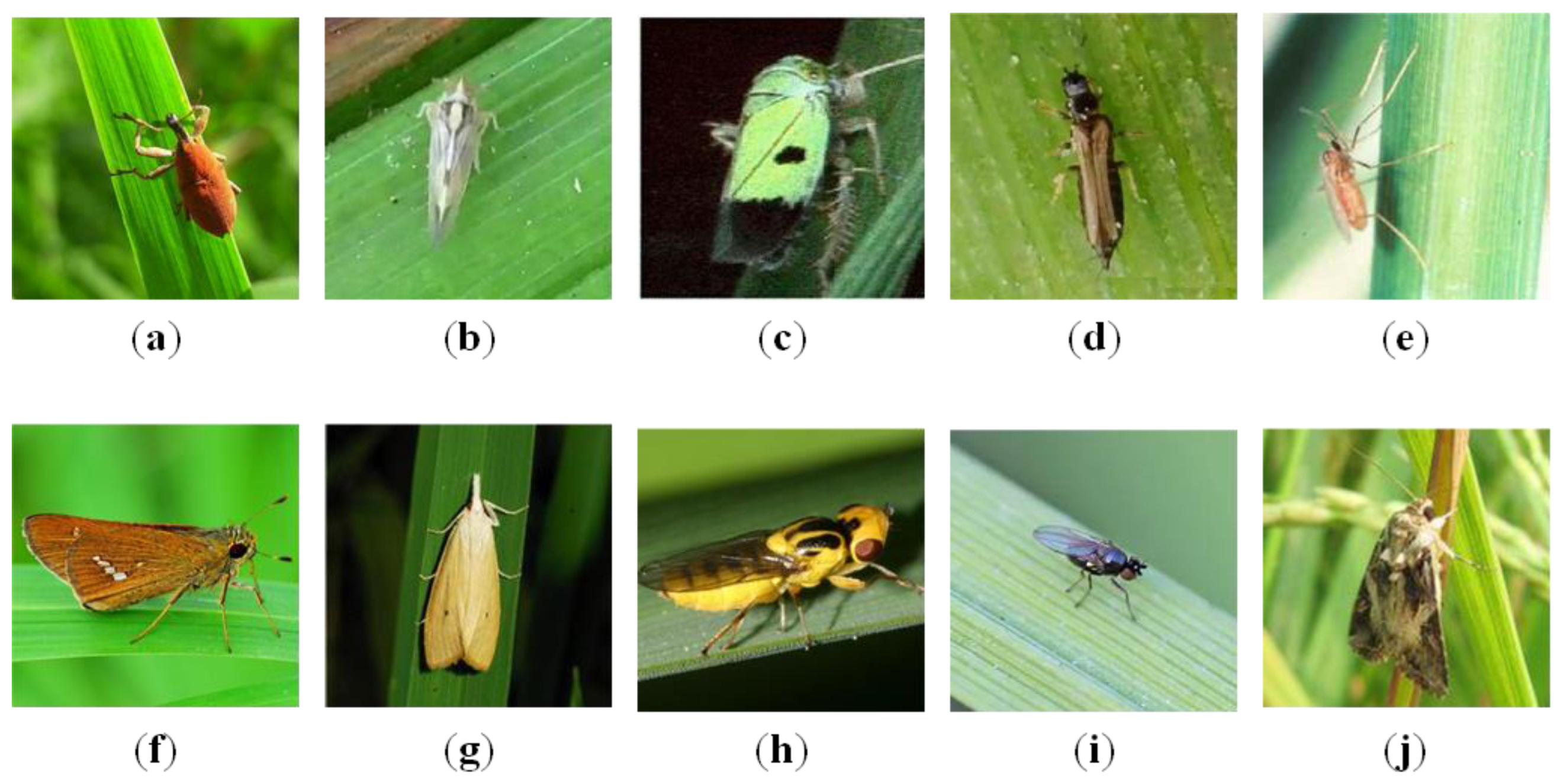

3.1.1. Data Collection and Splitting

IP102 is the largest publicly available pest image dataset in agriculture, containing 75,222 images across 102 pest categories. However, it includes many duplicates, irrelevant, and misclassified images, leaving only a few usable samples. In this study, we extracted rice pest images, removed duplicates, cleaned the data, and manually reviewed it with the help of experts from our university’s Plant Protection College, resulting in 4226 valid samples. The rice pests were annotated in YOLO format using LabelImg 1.8.6. The annotation adopts a double-blind protocol, with two people independently annotating. If there are differences in the annotation boxes or categories, they will be reviewed by experts from our university’s Plant Protection College. The new dataset, named RicePest-10 (RP10), contains 10 rice pest categories, shown in

Figure 7. These include

Curculionidae (weevils),

Delphacidae (planthoppers),

Cicadellidae (leafhoppers),

Phlaeothripidae (thrips),

Cecidomyiidae (gall midges),

Hesperiidae (skippers),

Crambidae (grass moths),

Chloropidae (grass flies),

Ephydridae (shore flies), and

Noctuidae (owlet moths). These 10 types are the most common rice pests. The class imbalance was not corrected during the sampling phase, but random partitioning was ensured during dataset partitioning to maintain a natural distribution for all subsets. RP10 was split into training (3375 images), validation (424 images), and test (427 images) sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, ensuring even distribution of pest categories across subsets for fair evaluation and effective training, as shown in

Table 1. Data augmentation techniques, including random brightness, motion blur, random occlusion, and salt-and-pepper noise, were applied to expand the dataset, resulting in the final RP10 dataset for the experiments.

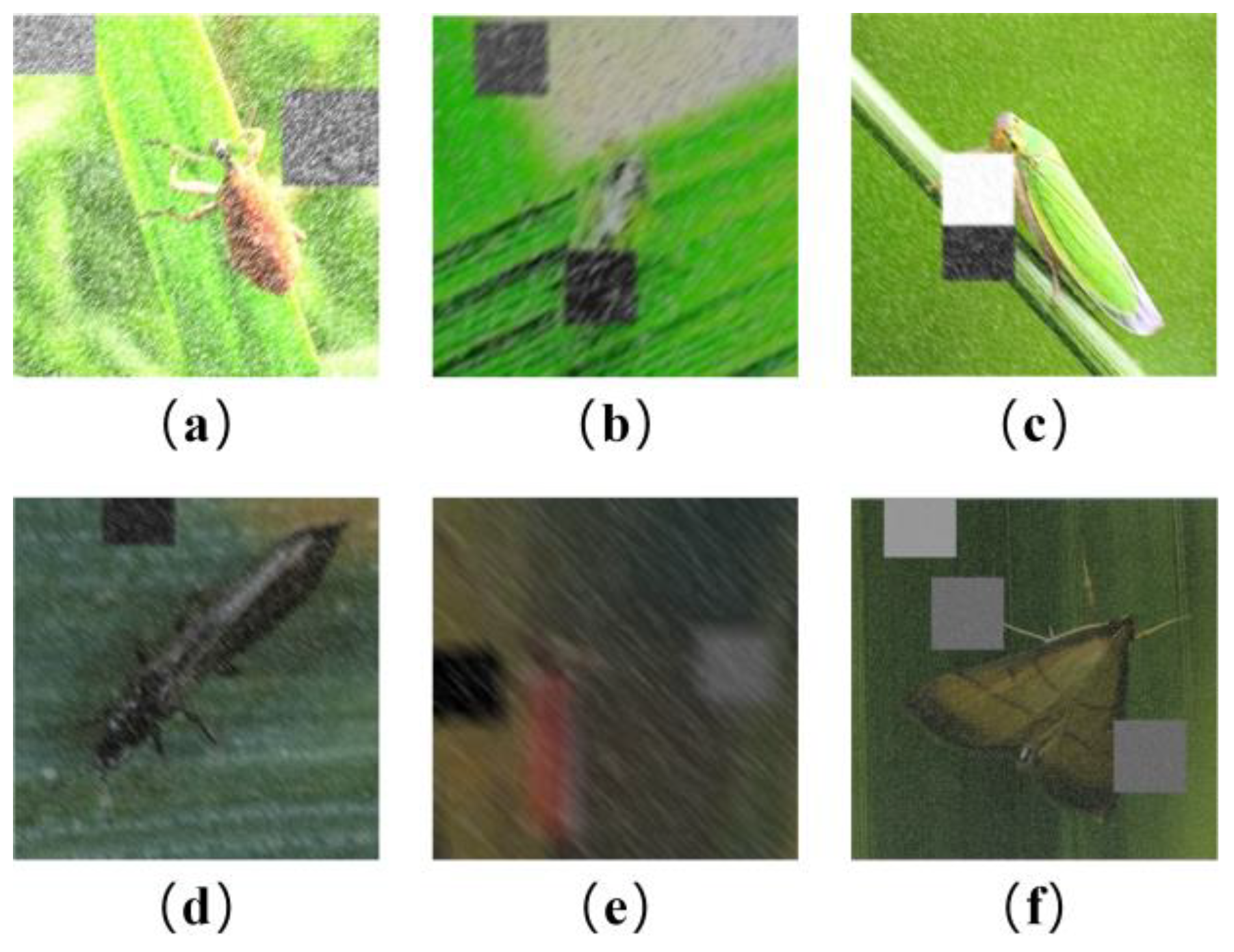

3.1.2. Data Augmentation

To enhance the generalization and robustness of the model, four data augmentation techniques were applied to the training set: random brightness, motion blur, random rectangular occlusion, and salt-and-pepper noise. These methods simulate various real-world interferences, such as complex lighting changes, plant oscillations, camera shake, leaf occlusions, and imaging noise, in rice paddy fields. Specifically, random brightness simulates light variations under weak light before and after sunrise, overexposure at noon, and low light at dusk; motion blur replicates the blurring and trailing effects caused by device shake or wind-induced plant movement; random rectangular occlusion mimics partial or large-area occlusion of pests by rice leaves or panicles; salt-and-pepper noise simulates noise from imaging devices or the environment. By applying these four augmentation techniques, the training set was expanded to double its original size, reaching 6750 images, while the validation and test sets remained unchanged, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability and robustness. Examples of the augmented training set are shown in

Figure 8.

3.2. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

To verify the effectiveness of the model, the experiments in this study were conducted on a Windows 10 operating system using the PyTorch 2.2.2 deep learning framework, with Python 3.11.11 as the programming language. The GPU used was an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti SUPER with 16 GB of VRAM. Additionally, the model was trained with a batch size of 32, 200 total training epochs, an initial learning rate of 0.01, a momentum factor of 0.937, and a weight decay coefficient of 0.0005 for the optimizer. It is worth mentioning that seed is set to 0. When the random seed is set to 0, all random operations such as model weight initialization, online data augmentation, sample sampling order, etc., are locked. In the same experimental environment, the training process can be replicated, so the results of each experiment are completely consistent. The specific parameter settings are shown in

Table 2.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively and objectively evaluate the performance of the proposed GAFNet model in rice pest detection, this study assesses the model’s performance based on Precision, Recall, mAP, Parameters, and FLOPs.

where P denotes Precision, representing the proportion of targets predicted by the model to belong to a specific category, and serves as an indicator of the model’s false positive rate. A higher P corresponds to fewer false positives. Additionally,

(True Positive) refers to the number of accurately detected pest bounding boxes, while

(False Positive) indicates the number of erroneously identified boxes.

where R denotes Recall, representing the proportion of true pest targets successfully detected by the model, reflecting the model’s false negative rate.

(False Negative) refers to the number of missed targets. A higher R indicates fewer missed detections. In this study, mAP is calculated by averaging the AP (Average Precision) of all 10 rice pest categories, offering a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s localization and classification performance. The definition of

is as follows:

where

c represents a specific class and

denotes the average precision for class

. Therefore, the calculation of mAP is given by Equation (9):

Here, represents the total number of classes.

Moreover, the number of parameters and FLOPs are crucial metrics for evaluating both the model’s performance and resource consumption. The number of parameters refers to the total count of all trainable weights and biases within the model, measured in “millions” (M), directly influencing the model’s storage requirements and peak memory usage, which is especially critical in edge deployment scenarios where storage and memory constraints are paramount. FLOPs, on the other hand, indicate the number of floating-point operations required for the model to perform a single forward inference on an input image of size 640 × 640, measured in “billions” (G). FLOPs serve as a standard for assessing computational complexity, and lower FLOPs can reduce inference latency and power consumption, making it more suitable for real-time processing applications. By considering these metrics, one can effectively assess the practical performance of GAFNet and provide a basis for its optimization.

3.4. Training Progress and Classification Performance of GAFNet

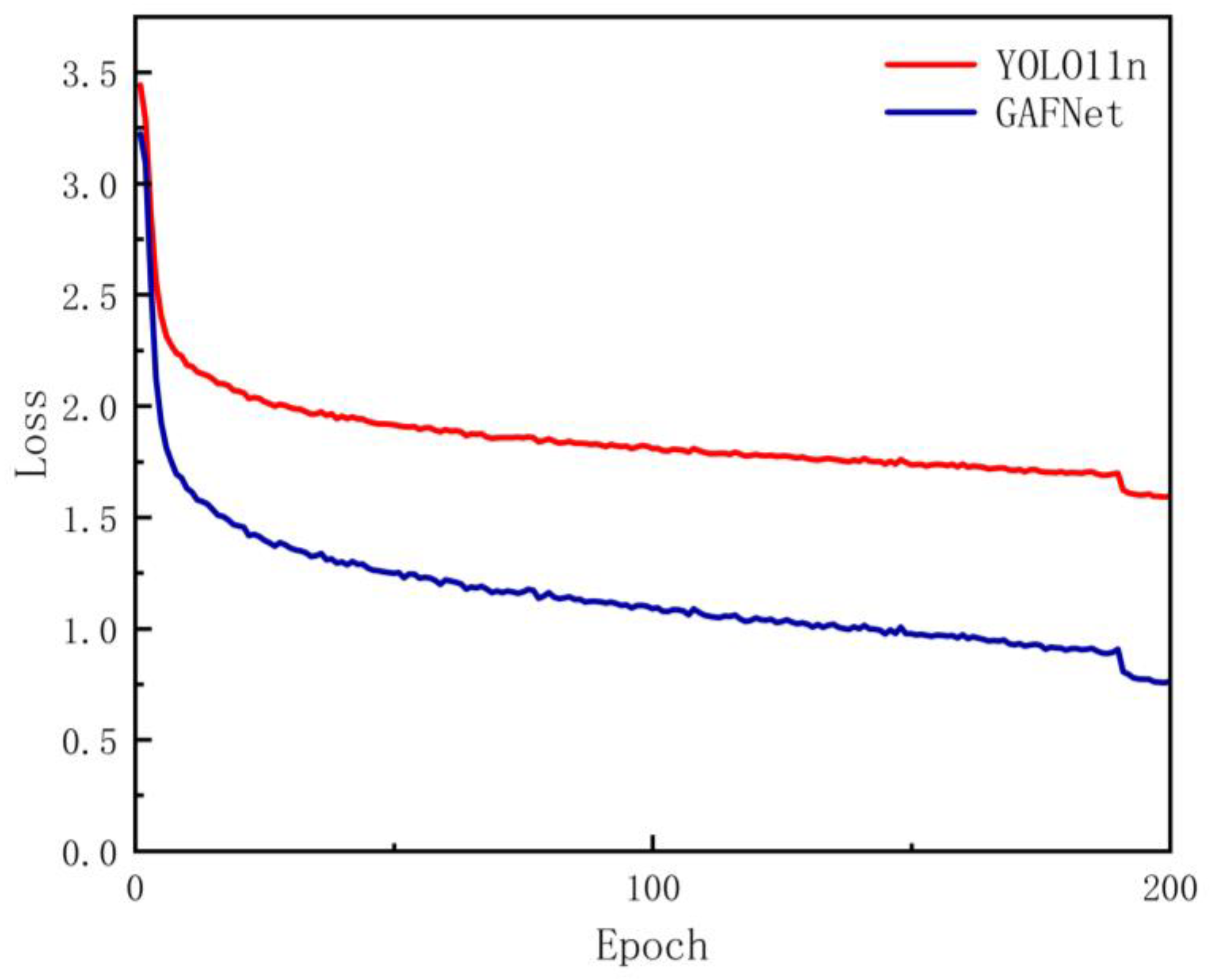

As illustrated in

Figure 9, the loss curve for different epochs during the training process demonstrates a smooth convergence trend, characterized by a sharp initial decline followed by a gradual reduction. Compared to YOLO11n, the GAFNet model proposed in this paper exhibits lower loss values and faster convergence, preliminarily validating the advantages of the proposed method during the model training phase. The evaluation results on the test dataset indicate that the GAFNet model achieves an accuracy of 89.8%, a Recall rate of 85.6%, and an mAP of 90.1%, while the model’s parameter count is only 2.45 M and its computational load is merely 5.0 GFLOPs. These results highlight the model’s strong performance-to-efficiency ratio, achieving high accuracy with minimal computational overhead.

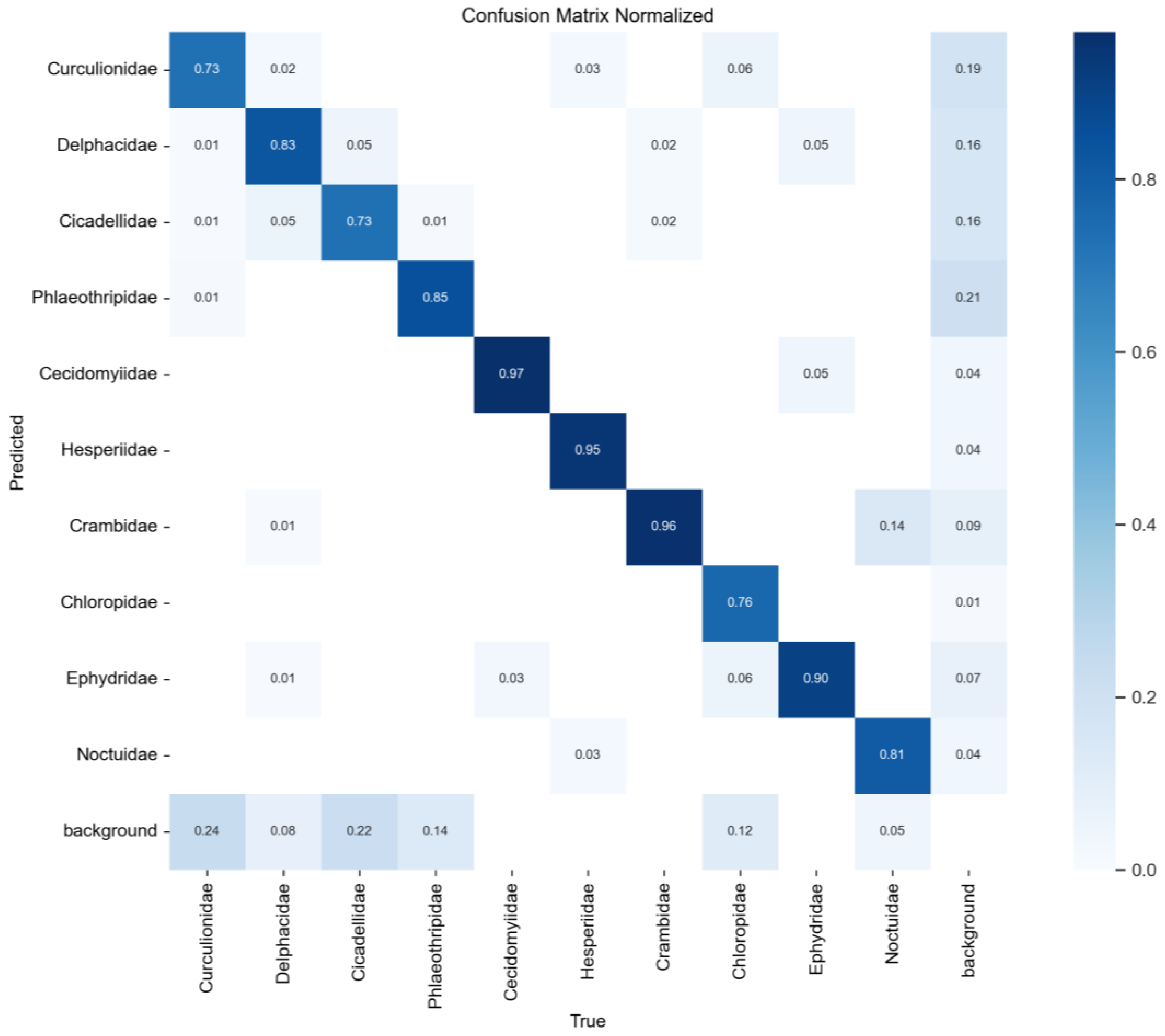

Furthermore, the use of confusion matrices is essential, as it provides detailed classification information for each category, helping to identify performance discrepancies across specific classes and uncover potential biases or imbalance issues. This is invaluable for guiding model optimization. As shown in

Figure 10, the confusion matrix of the GAFNet model’s performance on the rice pest classification task illustrates clear diagonal elements, demonstrating effective differentiation among all 10 categories. Among these,

Cecidomyiidae,

Crambidae, and

Hesperiidae show the highest identification rates, indicating that the model has effectively learned the features of these categories.

Delphacidae,

Phlaeothripidae, and

Ephydridae also exhibit favorable identification performance with relatively high accuracy. In contrast,

Curculionidae and

Cicadellidae have the lowest recognition rates, often being misclassified as background or other similar categories, primarily due to factors such as leaf obstruction, the small size of the pests, and complex backgrounds. Through the confusion matrix, GAFNet’s overall high recognition accuracy and exceptional category discrimination capability in the rice pest classification task are further validated.

3.5. Ablation Study and Contribution Analysis of Improvement Modules

To assess the contributions of various enhancements to model detection accuracy and lightweight optimization, this study conducts a progressive ablation experiment on the rice pest dataset. Using YOLO11n as the benchmark, we ensure strict consistency across hardware, software, training hyperparameters, and data augmentation strategies. Subsequently, we incrementally integrate GAM-SPP, C3-EFSA, EGDetect, and FECIoU into the network. The results of the ablation experiment, as presented in

Table 3, highlight the contributions of each enhancement module in terms of both detection precision and model efficiency.

As shown in

Table 3, we first replace the SPPF in YOLO11n with the proposed GAM-SPP. The modified model, with a slight increase in parameters and computational cost, improves mAP from 88.5% to 89.5%, and significantly boosts Precision by 1.9%. This demonstrates the advantage of multi-scale context and attention synergy in enhancing mAP and Precision. Building on this, we replace all C3k2 layers in the backbone with C3-EFSA, incorporating a three-way parallel structure with 3 × 3, 5 × 5 DWConv and 3 × 3 group convolutions. After fusion, we introduce the lightweight ECA, which not only increases Recall by 2.8% and elevates mAP to 89.9%, but also reduces parameters to 2.64 M and FLOPs to 5.7 G through the sparse computation of DWConv, achieving higher accuracy with lower computational cost. Subsequently, we replace the detection head with EGDetect, where all 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 standard convolutions are replaced by an enhanced composite structure combining EGConv, SE, and SiLU. The main and lightweight branches are concatenated for output, maintaining mAP while reducing parameters to 2.45 M and FLOPs to 5.0 G, further validating the lightweight potential of EGConv and SE attention in the detection head. Finally, the FECIoU loss is introduced, adding a minimal stabilization term

and a difficulty-weighted factor

to the IoU exponent in CIoU, further boosting Recall by 1.4% and achieving an mAP of 90.1%, with no increase in parameters or FLOPs. This confirms the loss function’s effectiveness in improving detection accuracy for small and partially occluded pests. Consequently, after all the synergistic improvements, the model achieves a 3.5% increase in Precision, a 4.2% increase in Recall, a 1.6% improvement in mAP, a reduction of 0.13M in parameters, and a decrease of 1.3 G in FLOPs, validating the effectiveness and complementarity of each module design. Although the performance improvement of GAFNet is incremental, it is more lightweight compared to YOLO11n, which makes its efficiency on edge hardware significantly higher. Under resource constrained deployment, GAFNet has a moderate mAP increase that translates into practical advantages.

3.6. Performance Comparison and Analysis of the GAFNet Model with Other Detection Models

To validate the advancement and practicality of the proposed method, a comparative analysis was conducted on the rice pest dataset with current mainstream detection models such as Faster R-CNN [

34], SSD [

35], RT-DETR [

36], and the YOLO series [

37,

38,

39,

40]. The performance comparison results of various models are shown in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, Faster R-CNN, SSD, and RT-DETR exhibit lower precision compared to the method proposed in this paper. They also have larger parameters and FLOPs, making them unsuitable for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. In contrast, the mAP of YOLOv5n to YOLOv12n ranges from 81.8% to 88.7%, with parameters ranging from 1.97 M to 6.03 M and FLOPs from 6.3 G to 13.1 G. The proposed GAFNet model, with a lightweight configuration of 2.45 M parameters and 5.0 GFLOPs, achieves an impressive mAP of 90.1%, improving by 1.6% over the baseline YOLO11n, with accuracy and recall rates increasing by 3.5% and 4.2%, respectively.

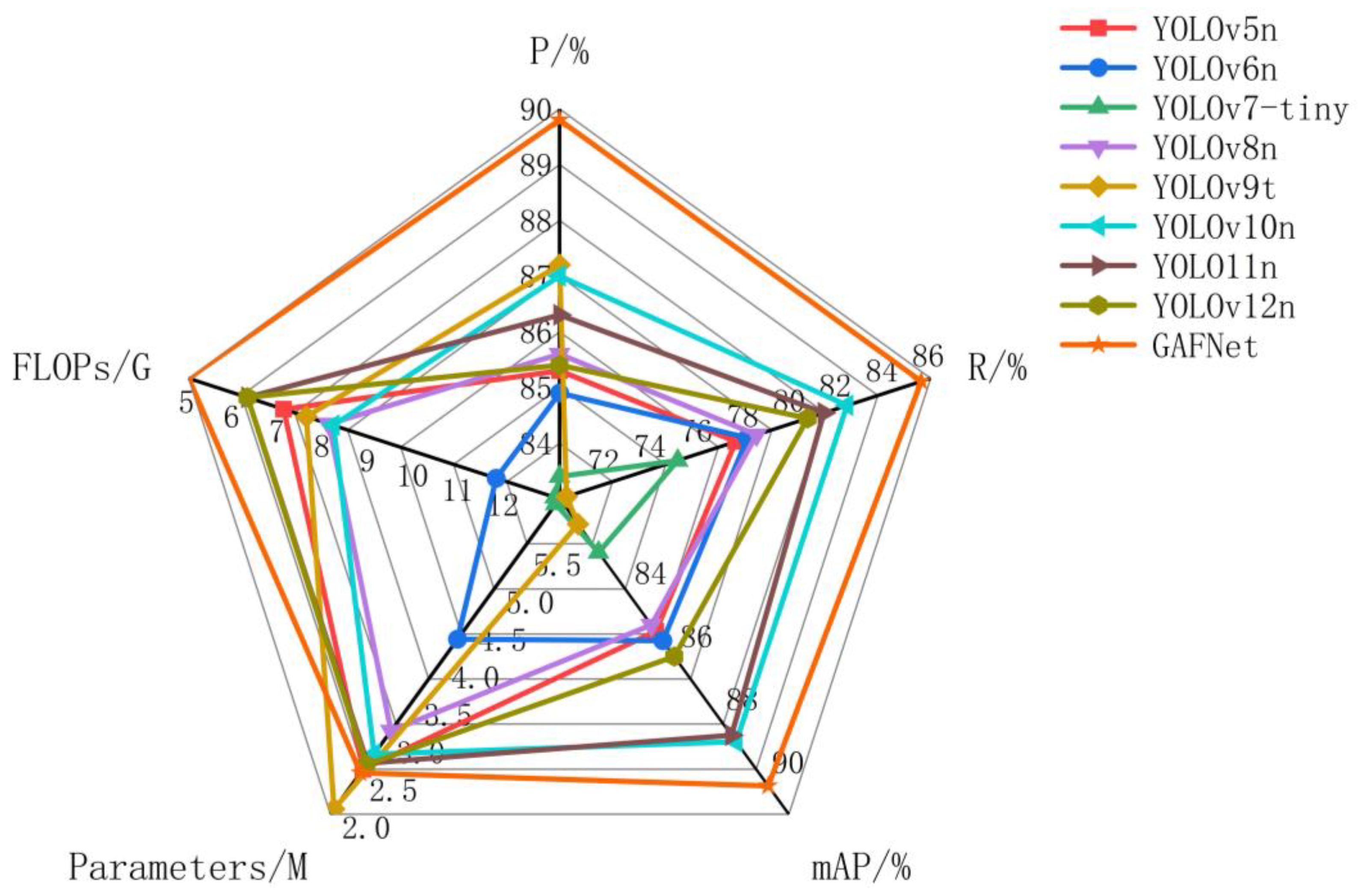

To visually compare the performance of the proposed GAFNet with the YOLO series, a radar chart based on

Table 4 is presented in

Figure 11. The larger the area covered in the radar chart, the better the model’s performance. It is evident from the chart that GAFNet excels in accuracy, recall, mAP, and FLOPs. Compared to YOLOv9t, although YOLOv9t has slightly fewer parameters than GAFNet, GAFNet outperforms it by 8.3% in mAP and has a significantly higher recall rate. Even when compared with YOLOv10n, which has the highest mAP in the YOLO series, GAFNet still achieves 1.4% higher mAP, with 39% fewer FLOPs and fewer parameters. Therefore, GAFNet is more suitable for pest detection in rice fields compared to the aforementioned methods.

3.7. Performance Evaluation of the FECIoU Loss Function Compared to Other IoU-Based Loss Functions

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed FECIoU loss function, while keeping the remaining modules unchanged, we compared it with the current mainstream IoU-based loss function, such as CIoU, Distance-IoU (DIoU) [

25], Efficient-IoU (EIoU) [

41], Generalized-IoU (GIoU) [

42], Scylla-IoU (SIoU) [

43], Wise-IoU (WIoU) [

44], and Alpha-IoU (

-IoU) [

45], Comparative analysis was conducted. The comparison results of various loss functions are shown in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, under identical experimental conditions, the mAPs of CIoU, DIoU, EIoU, GIoU, SIoU, WIoU, and

-IoU were 89.9%, 87.4%, 86.8%, 87.8%, 89.0%, 88.2%, and 87.1%, respectively, all lower than the FECIoU proposed in this paper. Further observation of the recall rate shows that FECIoU leads other loss functions with 85.6%, indicating a significant reduction in missed detections on slender targets. In terms of accuracy, FECIoU also leads with 89.8%, indicating that it can reduce background false alarms while maintaining target localization accuracy. Overall, FECIoU achieves a better balance between gradient magnitude and convergence stability by introducing the minimal stabilization term

and difficulty-weighted factor

, making it more suitable for practical scenarios such as rice field pests with small targets, elongated shapes, and complex backgrounds. Therefore, compared to other IoU-based loss functions, FECIoU is a better choice for detecting pests in rice fields.

3.8. Visual Comparison of Detection Capabilities Between GAFNet and Baseline Models

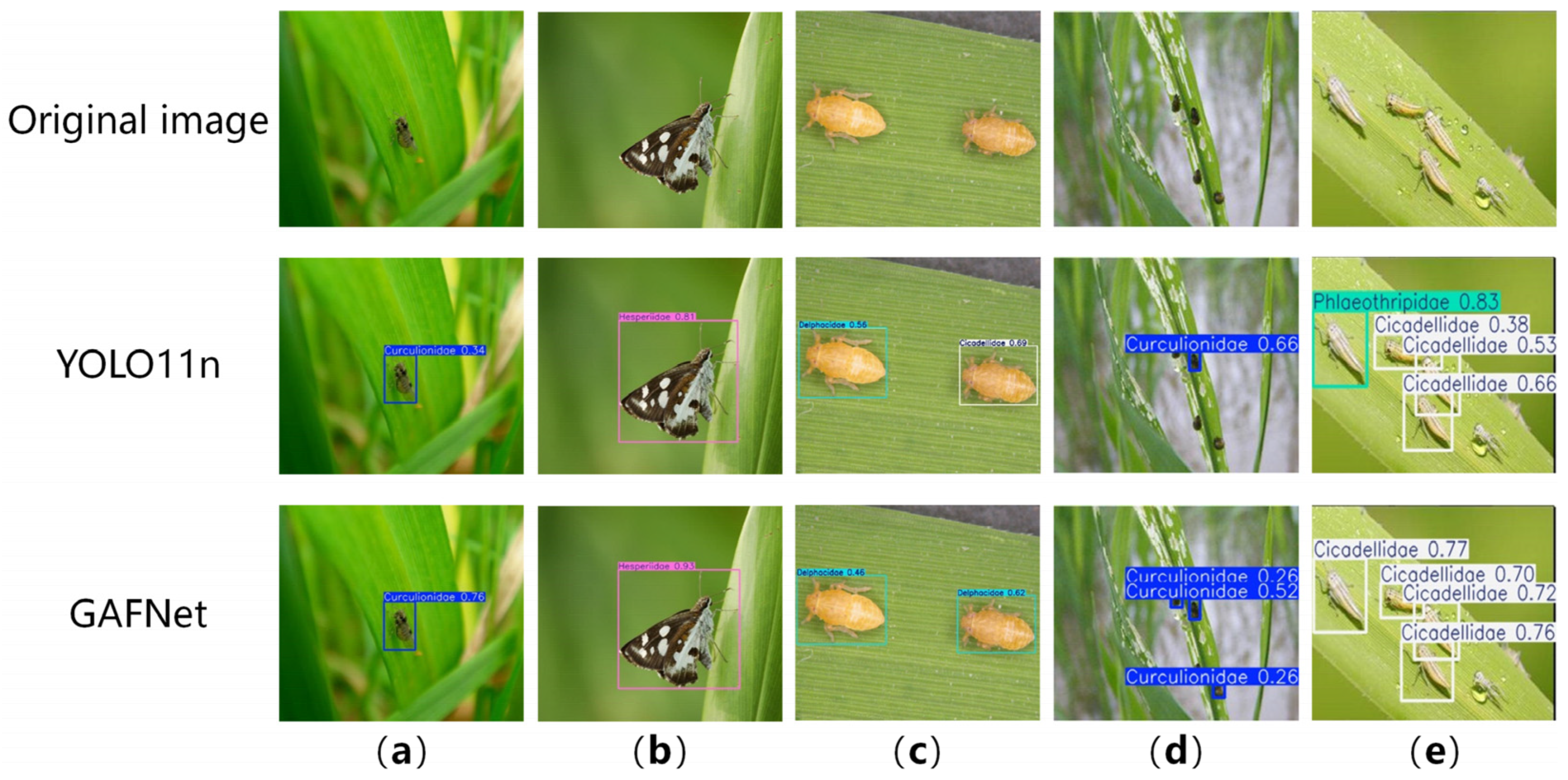

To more intuitively assess the detection capability and feature focusing effect of the GAFNet model in real rice field scenarios,

Figure 12 shows the detection results for various pests. As illustrated, the top row shows the original RGB images without detection, the middle row shows the detection results from the original YOLO11n model with final detection boxes overlaid, and the bottom row displays the detection results from the GAFNet model with final detection boxes overlaid.

It is clear that the YOLO11n model suffers from false negatives and false positives in detecting certain pests. For example, in column (d), Curculionidae is partially missed; in column (c), a Delphacidae is misclassified as a Cicadellidae; and in column (e), a Cicadellidae is misclassified as a Phlaeothripidae. In contrast, the GAFNet model correctly detects all pests, accurately locates them with high confidence, demonstrating the robust performance of the improved model for pest detection in rice fields.

The heatmap, utilizing a gradient color effect, effectively visualizes the distribution of data across different regions, further highlighting the advantages and optimization of the GAFNet model. As shown in

Figure 13, the GAFNet model significantly outperforms the original model in detection performance. The gradient from blue to red visually represents the model’s attention focus across the entire image: warm-colored regions consistently highlight the pest contours, while cold-colored, low-activation areas at the edges clearly delineate the background leaf veins. This indicates that the model effectively suppresses interference from leaf textures and rice panicle shadows.

In particular, for elongated pests, the red heatmap region extends continuously along the pest’s long axis without interruption, validating the stable regression capabilities of EGDetect and FECIoU for targets with extreme aspect ratios. In leaf-occluded scenes, the highlighted pixels focus exclusively on the exposed core texture of the pest, with the background remaining predominantly cool, reflecting the multi-scale attention of GAM-SPP in filtering out redundant information. In densely clustered scenes, each pest corresponds to a distinct heatmap spot, with no large-scale dispersion between neighboring individuals. This demonstrates the ECA channel attention mechanism of C3-EFSA in successfully distinguishing high-frequency texture variations. Overall, the heatmap closely aligns with manually annotated regions, providing clear validation of the lightweight improvements in accurately focusing on key pest features under complex field conditions.

3.9. Evaluation of the Generalization Performance and Robustness of the GAFNet Model

To thoroughly evaluate the generalization ability of the GAFNet model, this study tests its robustness and transferability across different crops and collection conditions using the publicly available AgroPest-12 dataset. This dataset differs significantly from the previously used ones in terms of pest categories, image collection environments, and distribution characteristics. It effectively tests the model’s ability to adapt to unknown agricultural scenarios. As shown in

Figure 14, these are example images for each pest category in the AgroPest-12 dataset.

As shown in

Figure 14, the dataset includes various crop scenes such as rice, vegetables, and fruit trees, with a total of 13,143 images. These are divided into 11,502 training images, 1095 validation images, and 546 test images. Compared to the previously used datasets, AgroPest-12 introduces several new pest types beyond rice pests, testing the model’s ability to classify other pest categories. Additionally, the images were collected from different regions, lighting conditions, and using various equipment. The background complexity and lighting variation are significantly higher than in the single rice field scenario, posing greater challenges for the model’s multi-scale perception. In this study, YOLO11n and GAFNet were both trained and tested on the AgroPest-12 dataset under the same experimental conditions.

Table 5 shows a comparison of the generalization performance of YOLO11n and GAFNet on the AgroPest-12 test set, with some visual results presented in

Figure 15.

As shown in

Table 6, GAFNet achieves an accuracy of 82.7%, a recall rate of 71.8%, and an mAP of 75.7% on this dataset. This represents an improvement of 4.4% in both accuracy and recall, and a 4.0% increase in mAP compared to YOLO11n. In terms of model parameters and computational cost, GAFNet remains lightweight, with only 2.45 M parameters and 5.0 GFLOPs.

Additionally, some visualization results are shown in

Figure 15. From the detection results of Caterpillars and Earthworms in columns (a) and (b), it is clear that YOLO11n misses some detections, whereas GAFNet successfully identifies them. In columns (c) and (d), the heatmaps for Ants and Bees show that GAFNet significantly outperforms the original model. The warm-colored highlighted areas precisely cover the contours of the insects, while the cooler, low-activation regions at the edges and background create a clear separation. This demonstrates that GAFNet has excellent generalization ability.

3.10. Embedded Edge Device Deployment Experiment

This study verifies the feasibility and deployment efficiency of GAFNet on edge devices by deploying it on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano embedded device, as shown in

Figure 14a. The software environment is configured with Python 3.8 and PyTorch 1.8, while the hardware is powered by an Arm Cortex-A78AE CPU and a 32-core Tensor GPU.

The experiment evaluates GAFNet’s practical feasibility for real-time pest detection in rice fields by measuring its detection speed in frames per second (FPS) on the edge device. As shown in

Figure 16c–f, the frame rate of GAFNet on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano remains stable between 19 and 24 FPS, demonstrating excellent real-time performance.

The practical deployment experiment demonstrates that the proposed GAFNet runs stably on resource-constrained edge devices, with response latency within acceptable limits. CPU and GPU resource utilization are efficient, and power consumption meets edge device requirements. This lays a solid foundation and provides technical support for future deployment of GAFNet in pest detection systems. Due to the lack of specific power consumption measurements, this is a limitation of the current work and will be tested under controlled battery conditions in the future. Although GAFNet has validated real-time capabilities on Nvidia Jetson Orin Nano, current edge testing is only based on a single platform, and performance on other edge devices remains to be evaluated. This work will be carried out in the future.

4. Conclusions

This paper addresses the key challenges in rice paddy pest detection, including small target size, high density, severe occlusion, complex background, and limited edge computation, by proposing a lightweight detection model, GAFNet, based on an improved YOLO11n. Firstly, a subset of the IP102 dataset, covering 10 rice pest species, is constructed, and data augmentation strategies, including random brightness, motion blur, random rectangular occlusion, and salt-and-pepper noise, are employed to enhance dataset diversity and model generalization. Secondly, the proposed GAM-SPP replaces the SPPF in YOLO11n, integrating channel and spatial dual attention while introducing multi-scale receptive fields, significantly improving the model’s ability to detect concealed pests. Thirdly, a new C3-EFSA module is introduced, replacing all C3k2 blocks in the backbone. By utilizing DWConv and grouped convolutions in a three-way parallel structure, followed by ECA integration, the model achieves a 2.8% increase in recall rate while reducing parameters and FLOPs. Next, EGDetect is designed, restructuring the 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 convolutions in Detect with a composite structure of EGConv, SE, and SiLU. This reduces the model to 2.45 M parameters and 5.0 GFLOPs while maintaining the mAP. Finally, the FECIoU loss function is proposed, introducing numerical stability terms and IoU-weighted indices for difficult samples to enhance recall in occlusion scenarios by an additional 1.4%. Experimental results show that GAFNet achieves 89.8% accuracy, 85.6% recall, and 90.1% mAP under a lightweight constraint of only 2.45 M parameters and 5.0 GFLOPs. Compared to the baseline YOLO11n, it improves accuracy, recall, and mAP by 3.5%, 4.2%, and 1.6%, respectively, while reducing parameters and computation by 5% and 21%. Cross-model comparisons demonstrate that GAFNet strikes the best balance between accuracy, model size, and inference cost, outperforming mainstream methods such as Faster R-CNN, SSD, RT-DETR, and YOLOv5n to YOLOv12n. In Integrated Pest Management (IPM), missed detections can result in delayed pesticide applications, allowing pest populations to proliferate and leading to infestations, increased chemical use and costs, and crop damage. Conversely, misdetections may prompt unnecessary pesticide applications, wasting resources and harming beneficial insects. Both scenarios undermine the fundamental principle of IPM, which is to optimize chemical use by applying fewer pesticides at the appropriate times. In summary, GAFNet provides a resource-efficient, accurate, and environmentally sustainable solution for early pest detection, enabling precision spraying and greener pest management in smart agriculture. Future work will focus on combining Transformer architecture, multimodal perception, and cross-seasonal transfer learning to further improve the model’s generalization and real-time performance under complex weather, lighting, and planting conditions.