1. Introduction

Coffee (

Coffea arabica L.) is one of the most economically valuable crops in tropical agriculture, and Brazil is the world’s largest producer and exporter of Arabica coffee, accounting for nearly half of global production [

1,

2]. Coffee cultivation sustains thousands of rural families and plays a crucial role in the socioeconomic structure of the southern region of Minas Gerais, where most of the country’s Arabica coffee is produced [

3]. However, productivity in these systems is often constrained by soilborne pathogens, among which plant-parasitic nematodes of the genus

Meloidogyne—commonly known as root-knot nematodes—are particularly destructive.

The most damaging species affecting Brazilian coffee plantations are

M. exigua,

M. paranaensis, and

M. incognita [

4]. The life cycle of these pathogens begins with the egg from which the second-stage juvenile hatches (J2). The juvenile penetrates the root system and migrates intercellularly until it reaches a region close to the central cylinder, forming the feeding site. From there, the second-stage juvenile undergoes three molts, and in the adult phase, the female remains immobile, feeding and producing eggs. The eggs are deposited in a gelatinous matrix that keeps them aggregated. This biological characteristic is one of the reasons why the distribution of root-knot nematodes is aggregated in the field.

These nematodes induce root galls that impair water and nutrient transport, ultimately reducing plant vigor, yield, and lifespan. Because the infection is primarily underground and visual symptoms in the canopy appear only at advanced stages, diagnosis is typically destructive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming [

5]. Consequently, infestations are often detected too late for effective management, leading to unnecessary or excessive chemical interventions.

Early and non-destructive diagnosis of nematode stress therefore represents a strategic advance for sustainable coffee management. Remote sensing technologies—particularly those employing multispectral and thermal imagery from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)—offer unique potential for this purpose. Systematic reviews indicate that UAV-based approaches enable the detection and quantification of plant diseases across multiple crops using high-resolution RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors, allowing the identification of subtle physiological and canopy-level alterations prior to the appearance of visible symptoms, despite operational and environmental constraints that still require careful planning and data management [

6].

Previous research has demonstrated that remotely sensed vegetation indices (VIs) can capture nematode-induced stress in crops such as soybean [

7], sugar beet [

8], and pine [

9]. However, very few studies have investigated nematode detection in coffee using UAV-based multispectral or thermal imaging. Martins et al. [

10] successfully discriminated coffee plants infested by

Meloidogyne spp. using RapidEye imagery and NDVI. The multispectral classification defined the spatial distribution of healthy and infected coffee plants, with an overall accuracy of 78% and Kappa coefficient of 0.71. Pereira et al. [

11] using the images taken by a low-cost camera (bands: (R) red, (G) green and (B) blue) mounted on a remotely piloted aircraft and machine learning algorithms estimated growth parameters of infected coffee plants subjected to 11 biological and chemical treatments. The results made it possible to estimate with satisfactory accuracy less than 26.5% of root mean square error (RMSE) the main physical parameters of coffee plants: chlorophyll, plant height, branch length, number of branches and number of nodes per branch. Nevertheless, these studies mainly focused on spectral responses, without exploring spatial or textural image information that can reveal canopy heterogeneity related to stress.

Texture analysis techniques, derived from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), can quantify spatial patterns in image reflectance and have proven useful in detecting disease and vigor variations in agricultural crops [

12]. When combined with spectral and thermal data, texture features may enhance the discrimination of stress levels, improving early detection capabilities. Despite this potential, textural metrics have rarely been applied to coffee pathology, and the combined use of multispectral and thermal UAV imagery for nematode detection remains largely unexplored.

Furthermore, the biennial production cycle of coffee introduces substantial canopy variability across years and seasons (rainy and dry), affecting leaf area, chlorophyll content, and reflectance characteristics [

13]. Understanding how nematode stress interacts with these seasonal dynamics is crucial for defining the optimal monitoring periods for early detection.

Considering these gaps, this study aims to evaluate the potential of UAV-based multispectral and thermal imaging, combined with textural analysis, to detect Meloidogyne exigua infestation in coffee plants under field conditions.

Specifically, the study investigates the relationships between root gall number and (i) vegetation indices, (ii) individual spectral bands, (iii) canopy temperature, and (iv) textural parameters derived from multispectral bands.

By analyzing data from two contrasting seasons—dry and rainy—we hypothesized that the symptoms caused by nematodes generate spectral and spatial indicators in coffee plants that can be detected using UAV to support early detection of the pathogen and precision management in coffee cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

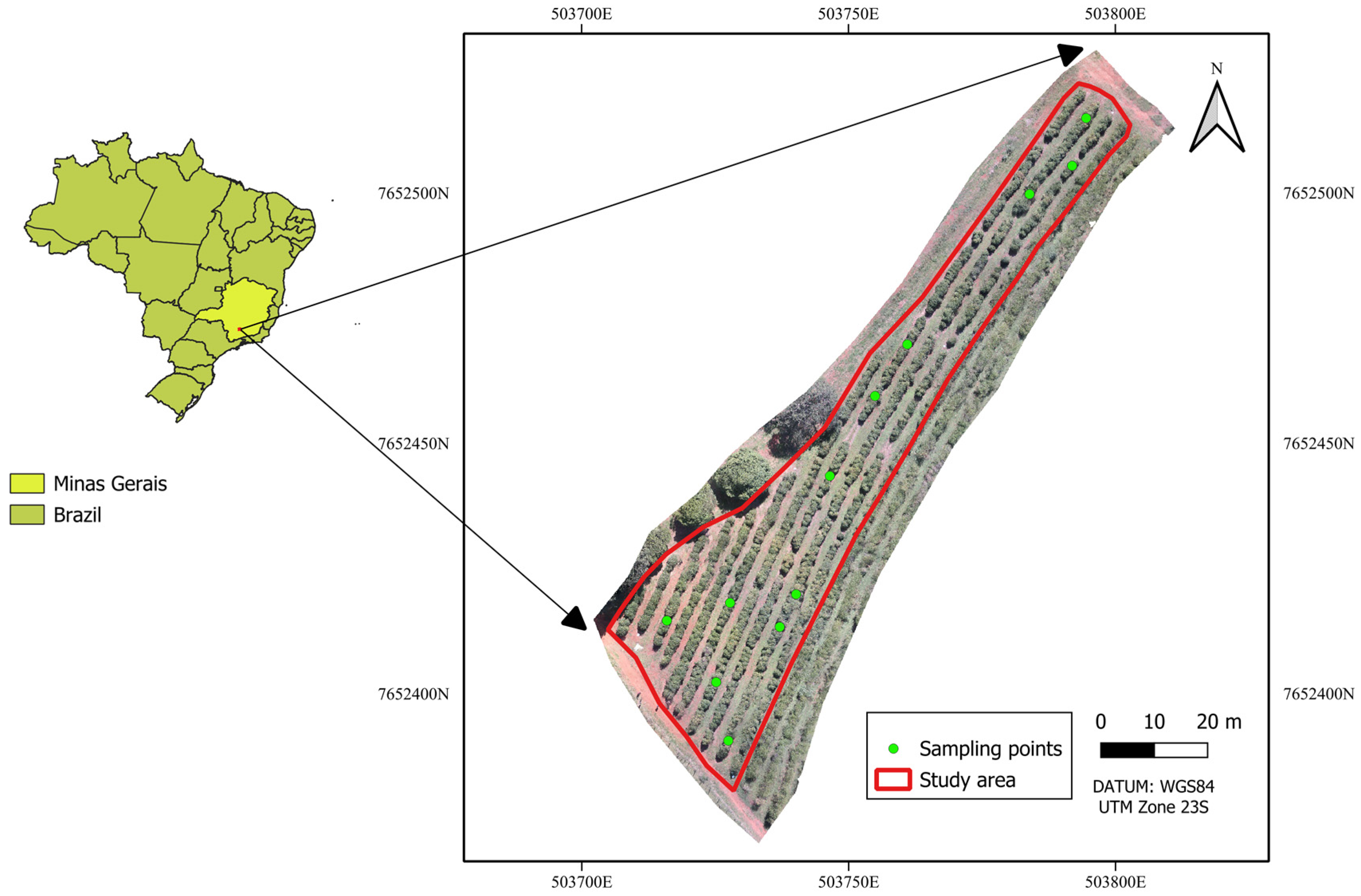

The experiment was carried out at the experimental coffee plantation of the Department of Agriculture (DAG), Federal University of Lavras (UFLA), Minas Gerais, Brazil (21°14′ S; 44°59′ W; altitude 918 m),

Figure 1. The study area consisted of

Coffea arabica Topázio variety, spaced 1.80 m between rows and 0.70 m between plants, established on gently undulating terrain. The plantation was healthy, with no recorded incidence of fungal, bacterial, or insect pests at the time of sampling.

The soil was classified as a dystrophic Red Latosol (Oxisol), with low natural fertility (

Table 1). Composite soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm layer under the canopy projection of the coffee plants and analyzed in the soil specialized laboratory (Lavras, Brazil) for chemical attributes.

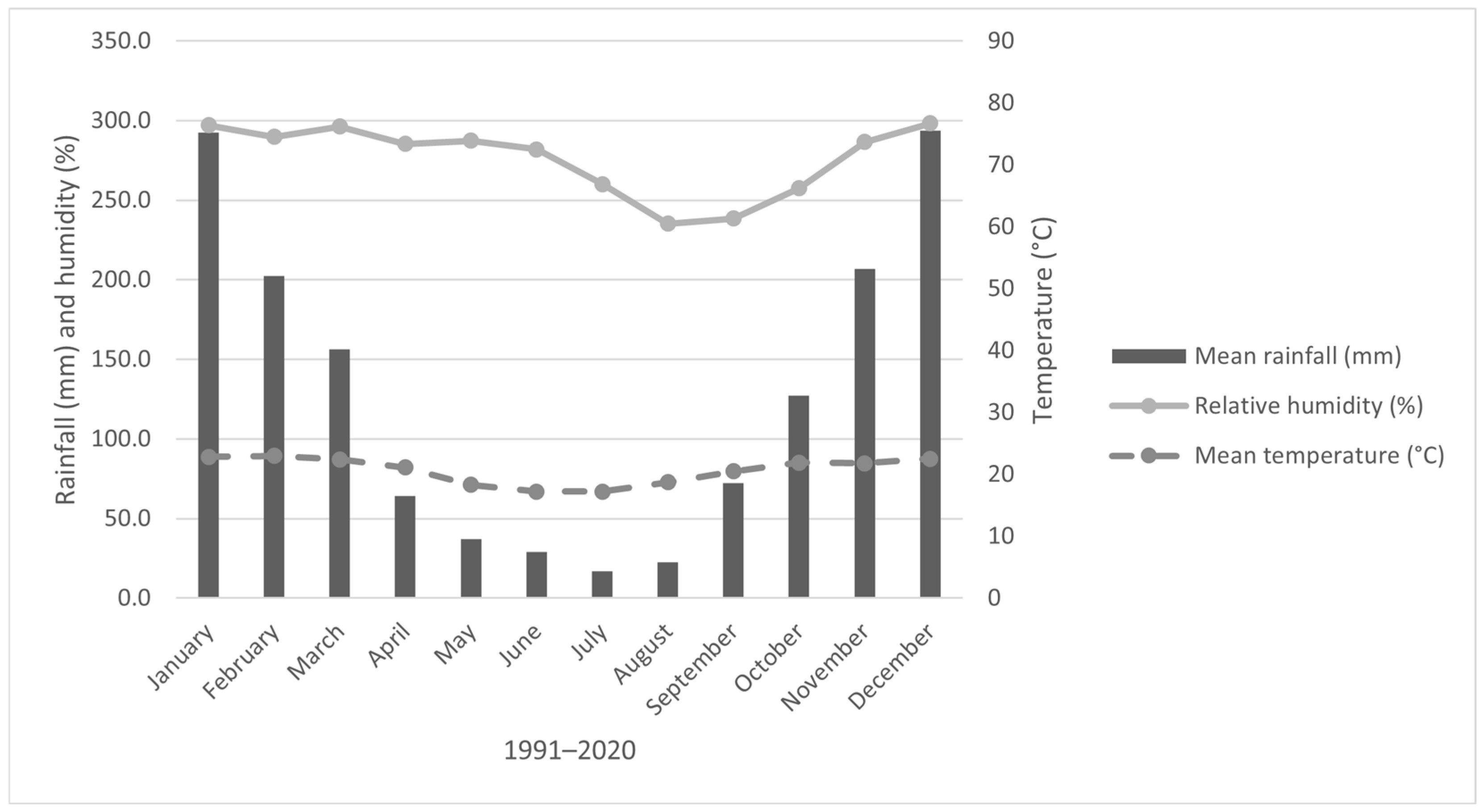

Meteorological conditions were obtained from the UFLA station of the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET). The regional climate is classified as Cwa (humid subtropical with dry winter and rainy summer) according to Köppen [

14]. The average annual temperature is 20 °C and mean annual precipitation is 1153 mm. Figures show the temporal variation in monthly rainfall, air temperature, and relative humidity from 1991 to 2020 (

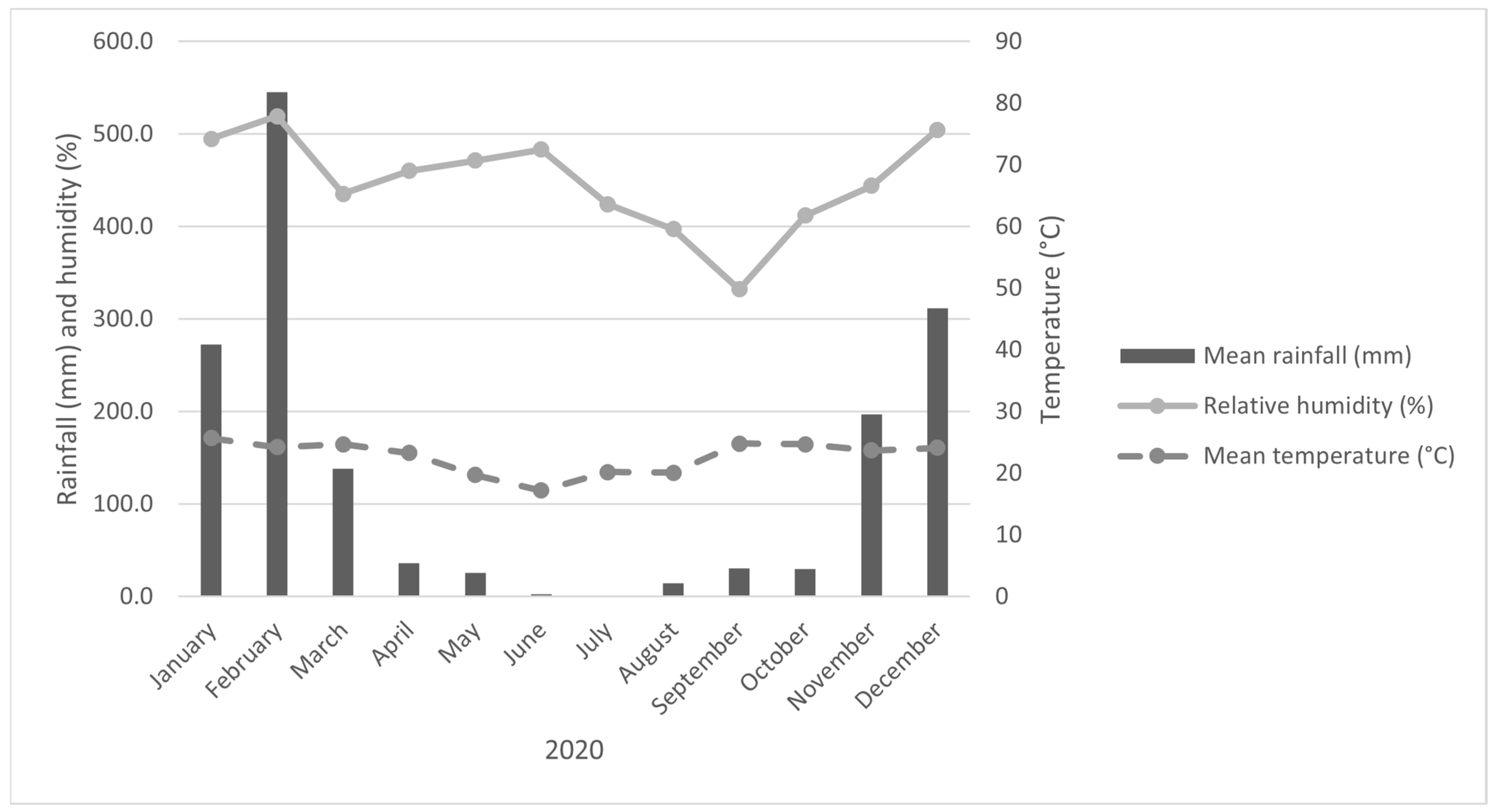

Figure 2) and in 2020 (

Figure 3). Overall,

Figure 2 highlights a clear distinction between the dry (May–September) and rainy (January–April and October–December) seasons, with substantial variation in rainfall and temperature across the year.

2.2. Field Sampling and Nematological Analysis

Prior to image acquisition, a nematological survey confirmed the presence of

Meloidogyne exigua using esterase electrophoresis protocol [

15]. Twelve coffee plants were selected for detailed evaluation, along with five ground control points (GCPs) used for image georeferencing. Each plant was georeferenced using a topographic GNSS (Global navigation Satellite System) receiver, model Trimble RTK R8 (Trimble Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

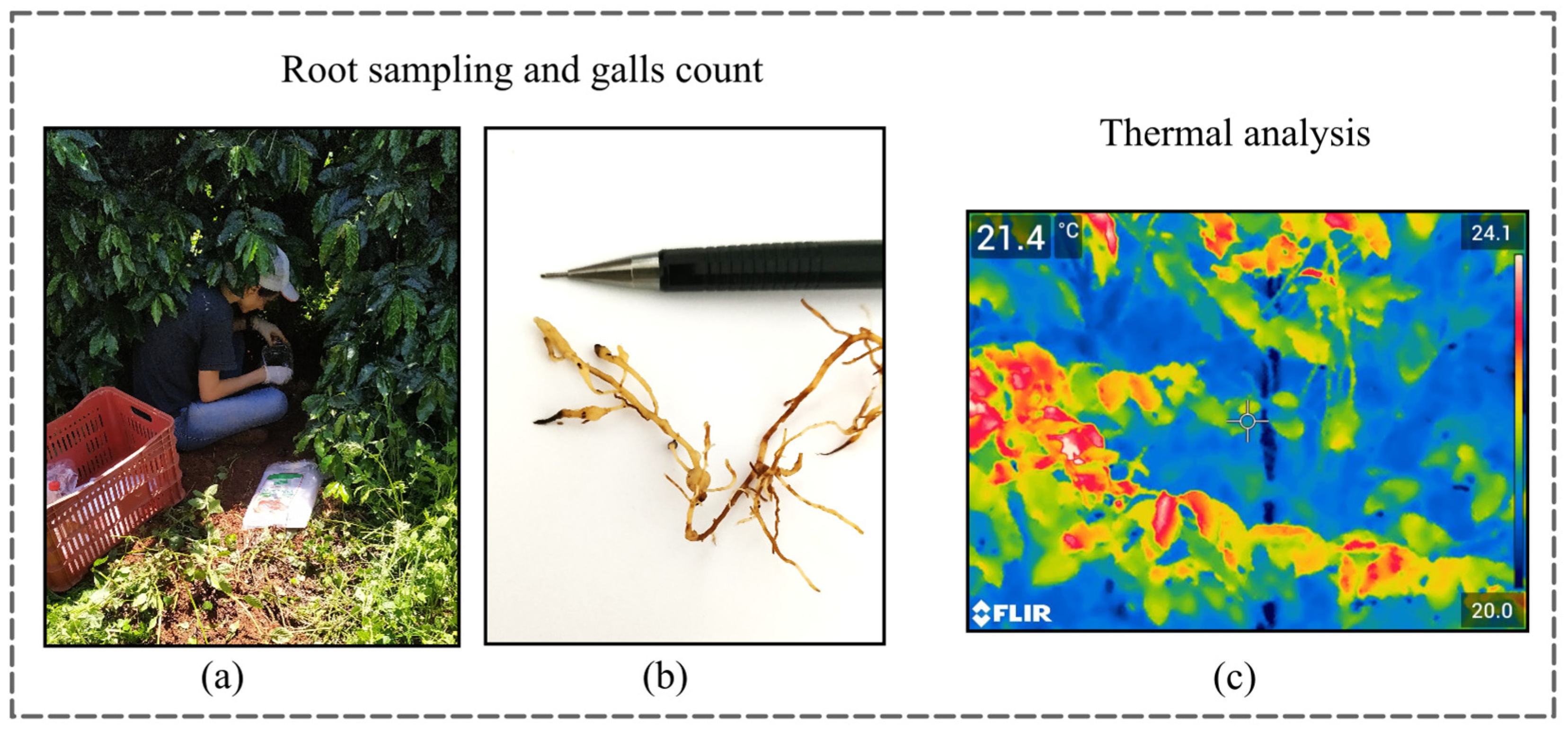

Root samples (~300 g) were collected at a depth of 0–20 cm within the canopy projection of each plant, targeting the active root zone where nematode populations are typically most concentrated. Sampling at this depth is consistent with standard nematode diagnostic protocols for perennial crops, as Meloidogyne spp. preferentially colonize fine feeder roots located in the superficial soil layers. Immediately after collection, the roots were rinsed under running water to remove soil particles without damaging the epidermal tissue, ensuring that gall structures remained intact and clearly visible. The number of galls per plant was manually counted following the procedure recommended for quantitative nematode assessment, and this value was used as the primary indicator of infestation intensity.

Leaf samples were collected during both monitoring campaigns (dry and rainy seasons) to assess potential changes in plant nutritional status associated with nematode stress. For consistency and to minimize within-plant variability, leaves were sampled from the third or fourth pair in the middle third of the canopy, following the standard guidelines for foliar diagnosis in coffee. Samples were taken from all four cardinal orientations to capture representative canopy conditions and reduce bias associated with sunlight exposure or microenvironmental differences. The samples were subsequently analyzed for macronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and S) and micronutrients (B, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn) in specialized laboratory (Lavras, Brazil). Leaf nutrient concentrations were later used to evaluate whether nematode infestation was associated with imbalances in plant nutritional status. Additionally, the visual condition of the canopy was assessed using the foliage rating scale proposed by Boldini et al. [

16], which provides a semi-quantitative estimate of defoliation and vigor.

Thermal data were obtained using a thermal camera model FLIR E75 (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR, USA) handheld infrared camera (spectral range: 7.5–14.0 µm), which is suitable for capturing canopy temperature variations associated with physiological stresses that affect transpiration. The camera was positioned approximately 1.5 m above the canopy apex to ensure complete coverage of the plant upper portion while maintaining consistent imaging geometry among samples. Thermal images were collected between 9:30 and 11:30 a.m. on 1 May 2020 (dry season), and 28 October 2020 (rainy season), corresponding to periods of increasing solar radiation when canopy temperature differences linked to stomatal regulation are more pronounced. All images were processed using FLIR Tools software 5.x to extract canopy temperature (°C) from the central region of each plant, minimizing edge effects and background thermal interference. These temperature measurements served as an additional indicator of plant physiological status, with potential relevance to nematode-induced disruptions in water relations.

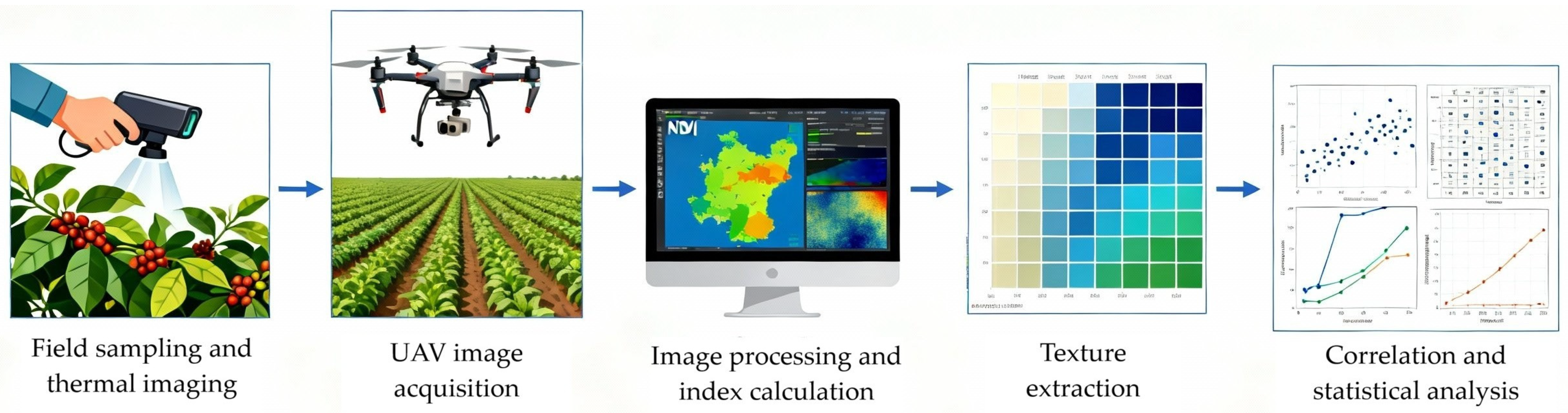

Figure 4 provides an overview of the field sampling and diagnostic procedures used in this study. Together, these images contextualize the integration of field measurements with labor-intensive root sampling process, root diagnostics, and thermal sensing employed in the experiment.

2.3. UAV Image Acquisition

A DJI Matrice 100 (DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, PRC). quadcopter equipped with a Parrot Sequoia™ multispectral camera (MicaSense, Seattle, WA, USA) (

Figure 5) was used for aerial surveys. The camera contains five sensors: four narrowband multispectral sensors—green (530–570 nm), red (640–680 nm), red edge (730–740 nm), and near-infrared (770–810 nm)—and one 16 MP RGB sensor.

Flights were performed autonomously at 40 m altitude, 80% frontal overlap, 50% lateral overlap, and 3 m s−1 speed. The flight schedule matched field sampling times in both seasons (11:30 a.m.–1:30 p.m.). Ground Control Points (GCPs) distributed in the area were used for geometric correction and radiometric calibration.

2.4. Image Processing and Vegetation Indices

The processing of the aerial multispectral images, a crucial step for quantifying canopy characteristics, was performed to generate the remote sensing products necessary for the analysis. The initial stage involved the creation of high-resolution orthomosaics, a procedure executed using the photogrammetry software Pix4Dmapper Pro 4.6.1 (utilizing an educational license), which followed the standard workflow of image alignment, dense cloud generation, and Digital Surface Model (DSM) construction, culminating in the obtaining of radiometrically corrected reflectance maps.

Subsequently, to ensure the positional accuracy of the data for site-specific analyses, the generated orthomosaics were subjected to georeferencing and spatial reprojection within a Geographic Information System (GIS) environment, using the QGIS 3.40 software. In this process, the data were projected into the UTM Zone 23S coordinate system (SIRGAS 2000 Datum), and the geometric correction was finalized with a first-order polynomial transformation and nearest-neighbor resampling, aiming to preserve the original reflectance values.

With the spectral bands duly corrected and aligned, the calculation of five distinct vegetation indices (VIs) commenced, which were computed using the raster calculator tool within the GIS environment, allowing for the quantification of canopy vigor and stress based on the spectral responses. This methodological approach ensured a comprehensive evaluation of spectral and textural behavior under realistic agricultural field conditions.

From the spectral bands, five vegetation indices (VIs) provide in

Table 2 were computed using the raster calculator:

The five vegetation indices were selected due to their sensitivity to physiological parameters that may be affected by nematode-induced stress. GNDVI is sensitivity to chlorophyll concentration. NDRE is less prone to saturation and more sensitive to physiological changes. NDVI is widespread used in vegetation monitoring biomass and canopy vigor including coffee plants. OSAVI was selected to minimize soil background effects, as nematodes infestations can lead to reduced canopy cover and increased soil exposure. NGRDI relies exclusively on visible bands and is sensitive to changes in leaf greenness.

Zonal statistics were calculated within 0.5 m buffers around each georeferenced plant to extract mean reflectance and index values. Both spectral bands and VIs were used in the subsequent correlation analysis [

22,

23].

2.5. Texture Feature Extraction

The present study deepened the spatial analysis of the canopy by deriving texture metrics from the spectral bands with significant correction number of galls [

24,

25], bands which demonstrated greater sensitivity to the physiological changes caused by nematode infestation. The method employed for extracting these textural features was the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) [

12,

26], a widely recognized technique for quantifying image heterogeneity, as implemented within the GLMC package [

27] in a statistical programming environment.

From the GLCM, eight Haralick features were calculated, describing different aspects of the image spatial pattern: mean, variance, homogeneity, contrast, dissimilarity, entropy, angular second moment, and correlation. To determine the most responsive spatial configuration, the sensitivity of the results was explored through the combination of three moving window sizes 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7 pixels, with five angular directions (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, and invariant). Following the calculation of these combinations, only the texture metrics that exhibited significant correlation coefficients |R| greater than 0.5 with the nematode gall counts were retained, ensuring that only the most relevant and significant features were included in the discussion and subsequent analyses.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses aimed evaluating the relationships between Meloidogyne exigua infestation and the remote sensing variables and were conducted within the R 4.5.1 statistical programming environment (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), ensuring the robustness and replicability of the results. Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate differences in nematode gall number between seasons and to assess the relationship between gall incidence and canopy temperature. Prior to hypothesis testing, data were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences in the mean number of nematode galls per plant between the dry and rainy seasons were analyzed using a paired t-test, considering each plant as a repeated measure across seasons. Statistical significance was determined at a probability level of p ≤ 0.05. The association between the number of nematode galls and canopy temperature was evaluated using correlation analysis and linear regression. The strength and direction of the relationship were quantified using the appropriate correlation coefficient, and regression lines were fitted to illustrate trends between variables.

The core of the analysis was the determination of associations between gall counts and the various predictor variables (spectral bands, vegetation indices, texture metrics, canopy temperature, and leaf nutrient content). For this purpose, Pearson correlation coefficients (R) were calculated, a standard method for measuring the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables, with a significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05 applied to all hypothesis tests.

The interpretation of the intensity of these correlations followed the strength classification proposed by specialized literature [

28]. Correlations were considered weak when |R| ≤ 0.3, moderate for values between 0.3 < |R| ≤ 0.6, and strong when |R| > 0.6. Finally, all graphical representations, including boxplots and scatterplots, were created using the ggplot2 package, while correlation heatmaps were carefully scaled to the range of −1 to +1, to facilitate the clear visualization of positive and negative associations.

Figure 6 illustrates the overall methodological workflow adopted in this study, from field measurements to data analysis. This workflow summarizes the integrated remote sensing and field-based diagnostic approach used in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Gall Number and Canopy Temperature

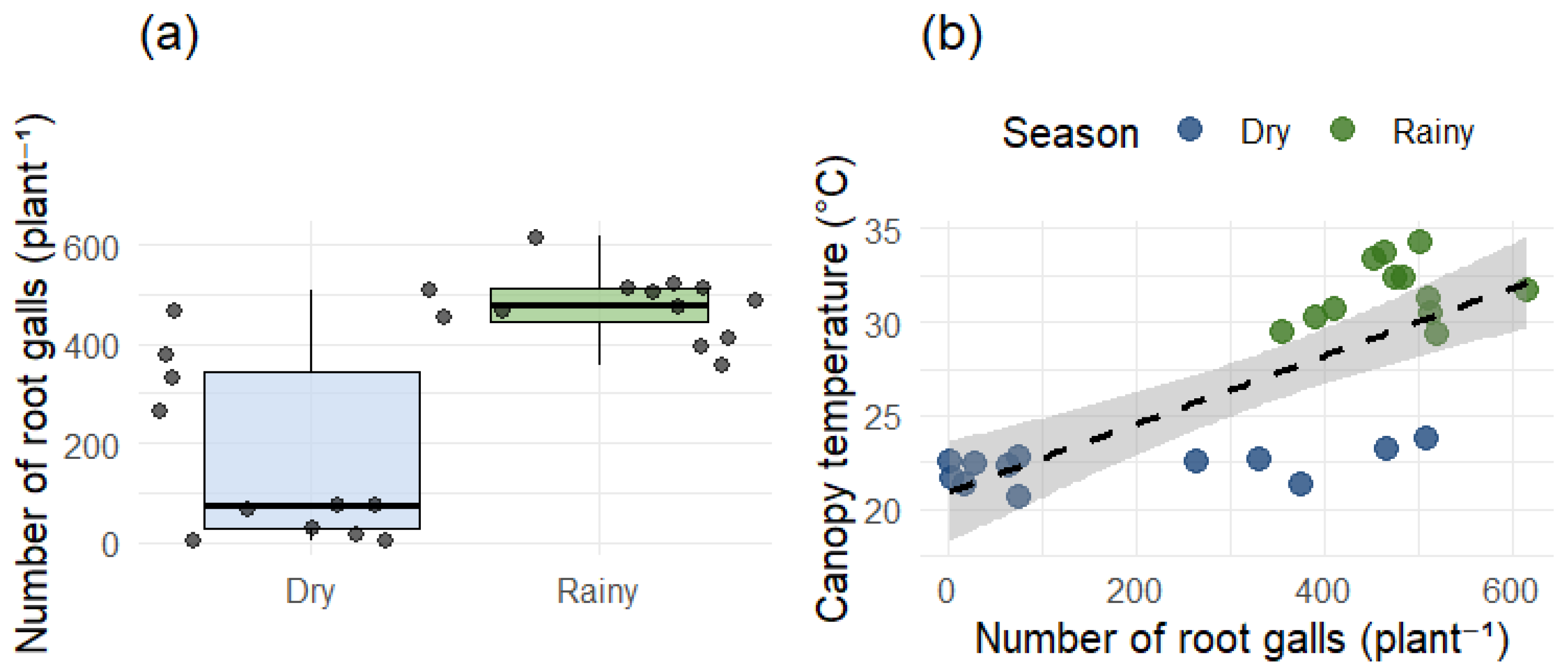

Root gall counts confirmed a heterogeneous distribution of

Meloidogyne exigua infestation among the seasons, with a mean of 475.17 galls per plant in the rainy season and a mean of 184.5 galls per plant in the dry season. The paired

t-test indicated a statistically significant difference in the mean number of nematode galls in coffee plants between the dry and rainy seasons (t = −4.99,

p ≤ 0.001), with gall incidence differing markedly between these two periods, indicating that nematode population levels do not remain stable across the sampling periods (

Figure 7a).

Canopy temperature showed greater seasonal variability. Mean canopy temperature in the rainy season (30.1 °C) was significantly higher than in the dry season (25.6 °C;

p < 0.01). A moderate positive correlation (R = 0.52;

p < 0.05) was observed between canopy temperature and gall number during the dry period, suggesting that nematode-stressed plants exhibited higher thermal emission, likely due to impaired stomatal conductance. In the rainy season the correlation was not significative (

Figure 7b). This result was likely observed because the nematode population did not reach a damage level capable of altering the average temperature pattern of the plants in an environmental condition that is also favorable to the coffee plants development.

3.2. Spectral Variables Correlations

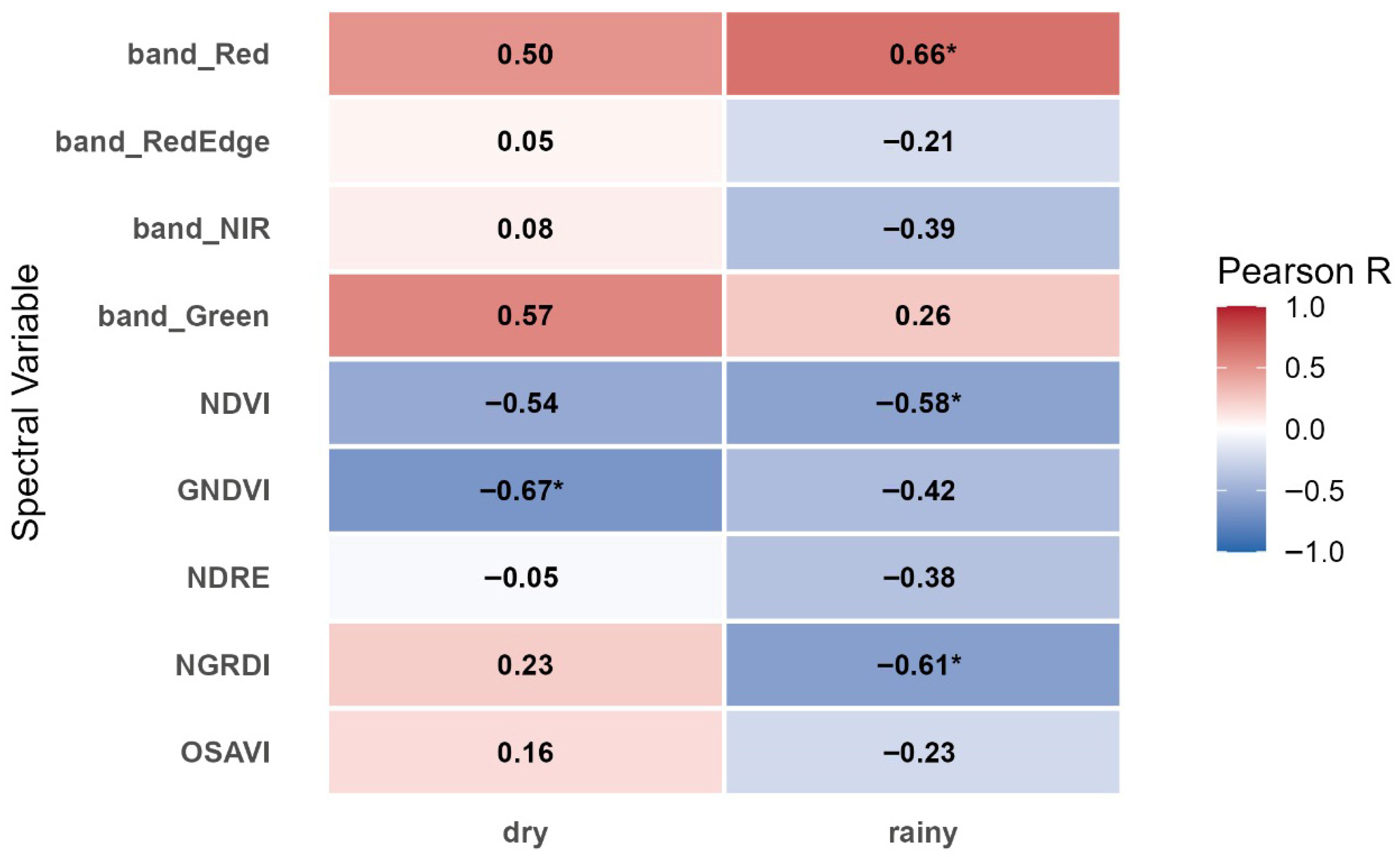

Spectral responses of the coffee canopy revealed distinct patterns between the dry and rainy seasons (

Figure 8). During the dry season, reflectance in the green (R = 0.57) and red (R = 0.50) bands exhibited positive correlations with gall number. In the rainy season, only the red band showed a strong positive and significative correlation (R = 0.66).

These results suggest that nematode stress reduces leaf chlorophyll and increases internal scattering heterogeneity, particularly under water-limited conditions typical of the dry period. The green band (530–570 nm) proved especially sensitive to early canopy changes caused by nematode-induced chlorosis.

Among the five vegetation indices evaluated, the GNDVI showed the strongest negative and significative relationships with gall number during the dry season (R = −0.67), while NDVI displayed a negative correlation but not significative (R = −0.54).

During the rainy season, the correlations between NDVI and gall number was significative and negative (R = −0.58) as well NGRDI which emphasizes the green and red bands showed the strongest negative correlation with gall number (R = −0.61), supporting its benefit for detecting chlorosis and partial canopy defoliation in plants.

3.3. Texture Features

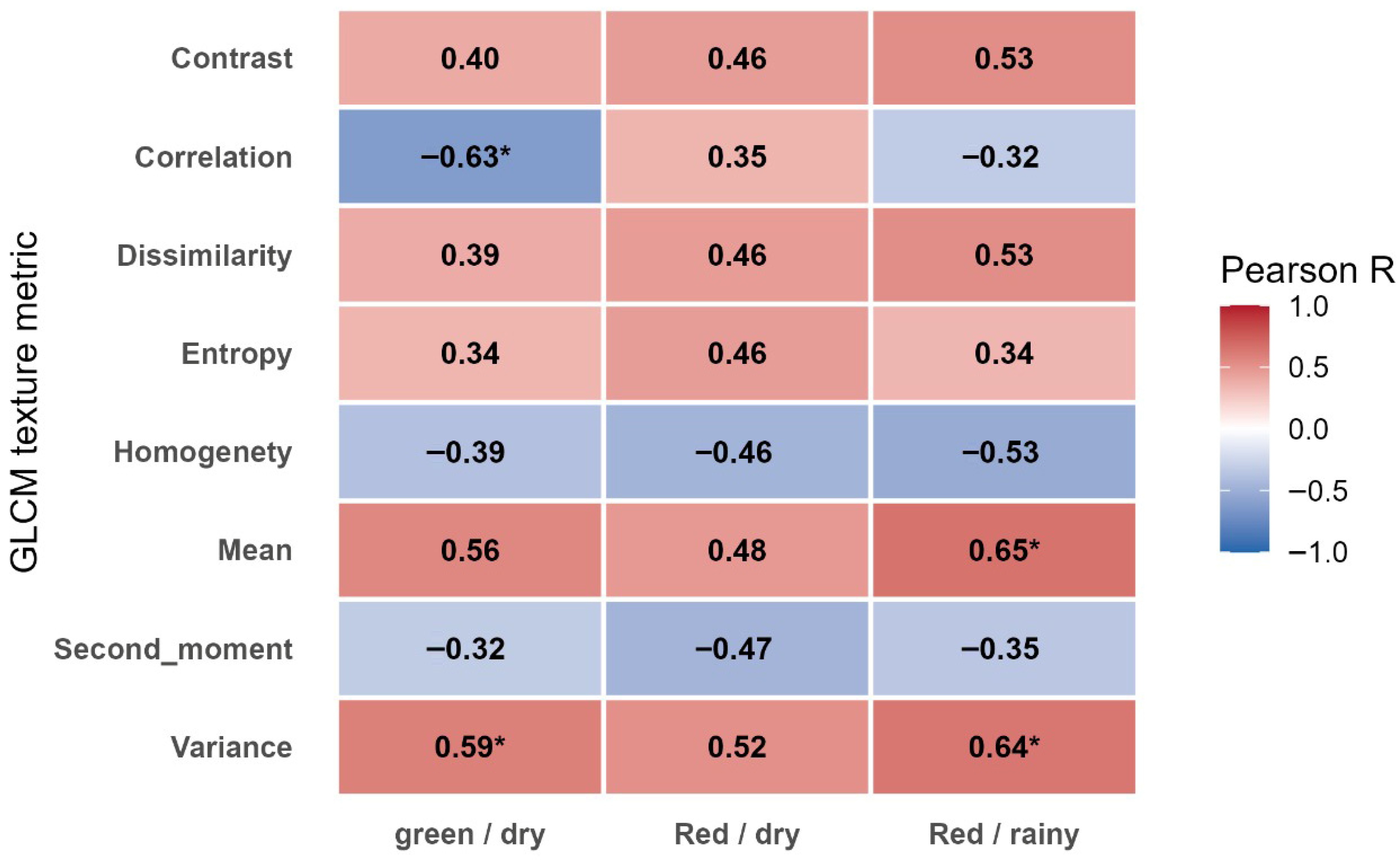

Texture metrics were derived from the green and red bands for the dry season and only the red band for the rainy season as they presented correlation values with a number of galls greater than 0.5.

Figure 9 summarizes the Pearson correlations between GLCM texture metrics and gall number for three conditions: green band during the dry season, and red band during both the dry and rainy seasons.

The textural metrics from the green and red bands captured subtle canopy pattern variations associated with nematode stress. In the dry season, the variance parameter of the green band exhibited strong positive correlations with gall number (R = 0.59; p < 0.01), indicating increased canopy heterogeneity in infested plants. Conversely correlation showed strong negative correlations (R = −0.63; p < 0.01), suggesting reduced canopy uniformity as infestation intensified.

During the rainy season the parameter of red band displayed positive relationships for texture metrics contrast and dissimilarity and correlation positive and significative for mean and variance. The results confirm that texture analysis can complement spectral indices, particularly under dry conditions when physiological stress is more evident and, in particular, during rainy season’s higher soil moisture and canopy density which can mask spectral contrasts, reducing detection accuracy.

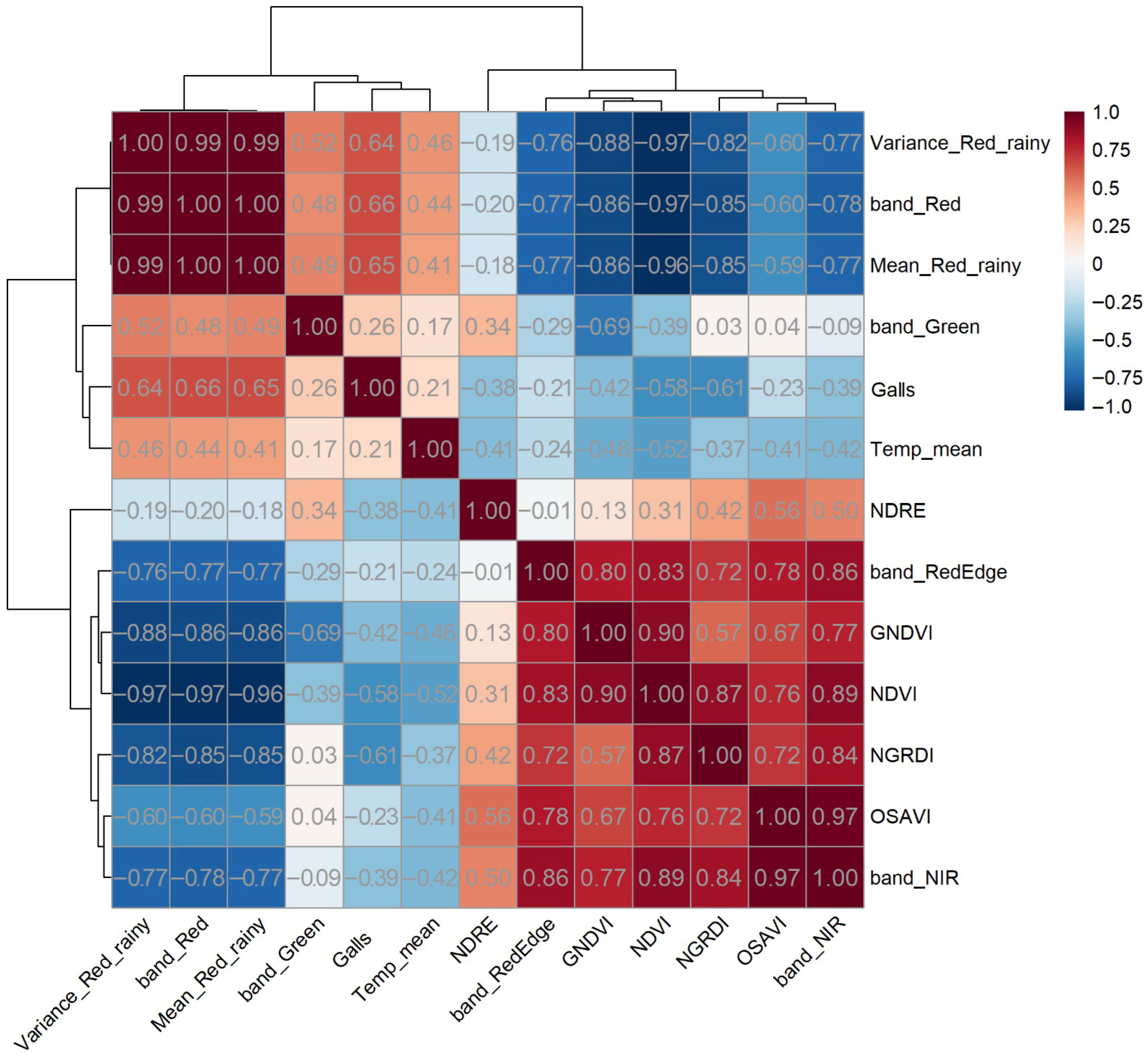

3.4. Integrated Correlation Analysis

Figure 10 presents the hierarchically clustered correlation matrix between Red-band texture metrics (rainy season), spectral variables, multispectral bands, canopy mean temperature, and gall number. The clustering reveals two major patterns: (i) the texture metrics (Variance and Mean) form a homogeneous, highly correlated block, showing moderate to strong negative correlations with vegetation indices and near-infrared bands; and (ii) spectral indices associated with vegetative vigor (NDVI, GNDVI, OSAVI, NGRDI, NDRE) cluster together with the NIR band, exhibiting very strong positive correlations among themselves. This spectral cluster also shows negative correlations with canopy temperature, reflecting higher transpiration rates in more vigorous plants.

Overall, gall number showed only weak correlations with the evaluated variables, indicating that during the rainy season, intense vegetative growth tends to mask spectral, thermal, and textural signatures associated with nematode stress. This pattern suggests that the remote detection of nematode-induced stress is strongly influenced by seasonality and may be more effective under conditions of lower vegetative vigor and higher water demand.

3.5. Nutrient Relationships

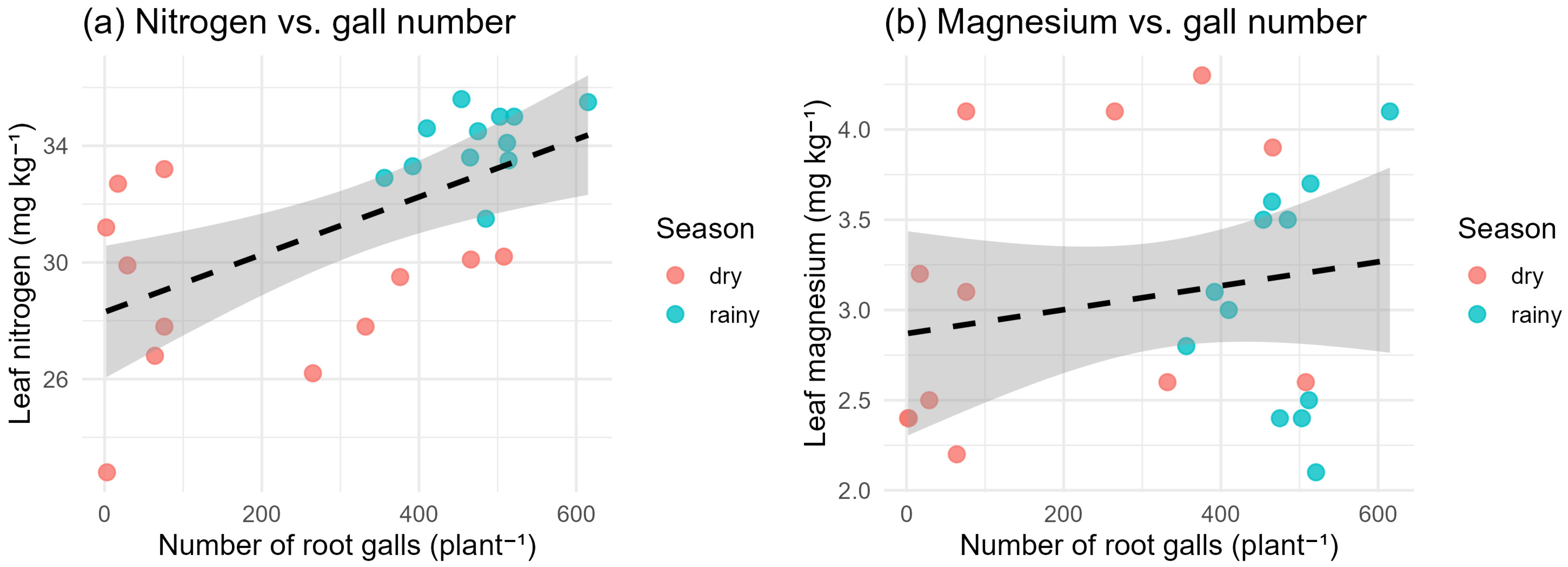

Leaf nutrient analysis revealed moderate negative correlations between gall number and leaf nitrogen (R = −0.56; p < 0.05) and magnesium (R = −0.48; p < 0.05), consistent with nematode-induced impairment of root uptake. Potassium and calcium exhibited weaker correlations (R ≈ −0.30). These nutrient deficiencies may have amplified the spectral differences observed, particularly in the green and red-edge regions.

Figure 11 illustrates the relationships between leaf nutrient concentrations and nematode infestation levels, expressed as the number of root galls per plant, for both the dry and rainy seasons. In

Figure 11a, leaf nitrogen shows a positive association with gall number, with a slightly upward regression trend and overlapping confidence intervals. This pattern indicates that, within the observed range, plants with higher gall counts tended to exhibit marginally higher leaf nitrogen levels.

Figure 11b shows a similar pattern for leaf magnesium, with a shallow positive trend between Mg concentration and gall number. However, the variability within and between season is high, indicating uncertainty in the association.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physiological Basis of Spectral and Thermal Responses

The results suggest that nematode infestation produces measurable changes in both spectral reflectance and canopy temperature.

Strong negative and significant correlation between the NDVI and GNDVI and the number of galls in the dry season are consistent with chlorophyll degradation and partial canopy defoliation induced by

Meloidogyne exigua. Nematodes disrupt the root system, reducing nutrient and water uptake and consequently impairing photosynthetic capacity [

29].

In this context is important to discuss the seasonal dynamics and detection window. The dry season offered superior separability between symptomatic and asymptomatic plants due to higher physiological stress levels, indicating that UAV monitoring campaigns should be prioritized during dry or early drought conditions for optimal diagnostic accuracy.

The higher canopy temperature observed in infested plants, particularly during the dry season, reinforces this interpretation. Elevated leaf temperatures are a known indicator of stomatal closure and reduced transpiration under biotic or abiotic stress [

30]. Similar relationships between nematode infection and canopy warming have been reported in soybean [

7] and sugar beet [

8]. These results demonstrate that thermal sensing can complement multispectral indicators to detect early physiological stress in coffee.

This finding suggests that the dry-to-wet transition period may represent the optimal window for UAV-based nematode monitoring, when stress symptoms become physiologically detectable but before visual canopy decline occurs. Similar seasonal effects were noted by [

11] in coffee and [

9] in pine nematode detection. Therefore, temporal planning of UAV surveys is essential to ensure diagnostic sensitivity.

Considering the risks that plant-parasitic nematodes pose to coffee plants, especially those belonging to the genus Meloidogyne, which can even lead to plant death, innovative strategies applicable to integrated disease management planning are necessary. An important aspect of plant-parasitic nematode biology is their aggregated distribution within a field, and this characteristic is an advantage for the application of remote sensing for pathogen detection. By using multispectral images to assess aboveground damage caused by nematode, it is possible to access important information about the occurrence and management options.

Recent findings by [

31] reinforce the diagnostic potential of remote sensing in nematode management. Their study evaluated the capacity of orbital multispectral imagery to discriminate the effectiveness of different nematicide treatments in coffee plantations, demonstrating that satellite-based reflectance data can reliably detect spectral alterations associated with plant-parasitic nematode infection as well as the development of the plants resulting from treatment applications. Applying random tree algorithm on multispectral images the authors succeeded discriminated accurately the most nematicidal treatments, with a global accuracy of 80% and 0.78 of Kappa coefficient. These results strengthen the growing evidence that remotely sensed spectral features are sensitive to the combined effects of root damage, canopy stress, and recovery processes. Moreover, Ref. [

31] emphasize the need for continued refinement of remote sensing techniques and analytical algorithms to enhance the precision and operational reliability of nematode control strategies, particularly in complex field environments where multiple stressors may overlap.

The combined use of spectral, thermal, and textural features can improve the understanding of nematode stress signatures and provides a conceptual basis for developing predictive models in future studies.

4.2. Role of Textural Information

The correlations found between gall number and green and red-band texture metrics in dry and rainy situation, especially variance, highlight the value of spatial information derived from UAV imagery. Texture captures fine-scale variations in canopy structure—such as leaf arrangement, density, and gaps—caused by uneven leaf loss or deformation due to nematode stress.

In previous studies that used textural variables for improving the fruit ripeness prediction and mapping, Ref. [

32] found variance variable from NIR band, significant correlation with fruit ripeness and, then contributed to the prediction models. Although the spectral variables were more important for the models, authors argue that the GLCM window smoothened information from leaves and fruits, reducing the sensitive of these variables. In the present study, textural can be more relevant according to the symptoms caused by nematodes infestation, demonstrated the potential of the use of this information in coffee crops.

The combination of high contrast with reduced homogeneity and angular second moment in rainy season for red band suggests that infested canopies exhibit greater spatial heterogeneity. This aligns with previous findings in cotton and citrus where canopy texture successfully identified localized disease or stress patches [

29,

33]. Because textural descriptors are relatively insensitive to illumination differences, they provide a robust complement to spectral indices under varying light or background conditions.

4.3. Integrating Multispectral, Thermal, and Textural Information

The combined analysis revealed that nematode stress signatures in coffee are multidimensional and manifesting spectrally (reduced chlorophyll reflectance), thermally (canopy warming), and spatially (increased heterogeneity).

This study suggests potential for predictive modeling. Machine learning approaches such as Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), Random Forest (RF), or Support Vector Machines (SVM) could be applied in future work to build diagnostic models using these combined features. Preliminary results from similar frameworks in citrus greening detection [

33] achieved over 85% classification accuracy using multispectral–texture fusion.

Ref. [

11] tested the effect of eleven chemical and biological products on pathogen control and, based on data collected from plant surface reflectance, classified the most effective treatments using machine learning algorithms. The possibility of involving robust analyses, integrating artificial intelligence, for example, with information from remote sensing, is probably the most promising in the field of early detection of plant-parasitic nematodes, and such advance will contribute to the sustainable management of crops.

4.4. Nutritional Interactions

The negative correlations observed between gall number and leaf nitrogen (N) and magnesium (Mg) concentrations reinforce that nematode stress in coffee extends beyond physical root impairment and contributes to biochemical and metabolic limitations at the canopy level. Nitrogen plays a central role in chlorophyll biosynthesis and protein formation; therefore, reductions in N availability diminish chlorophyll content and directly alter reflectance in the green and red-edge spectral regions, which are highly sensitive to pigment concentration and leaf internal structure [

17]. Magnesium, as the central coordinating atom of the chlorophyll porphyrin ring, is equally critical for maintaining photosynthetic efficiency, stomatal conductance, and photochemical stability. Deficiency in Mg is commonly associated with reduced CO

2 assimilation, increased photooxidative stress, and pronounced spatial heterogeneity in leaf pigmentation, all factors capable of generating detectable spectral variation in multispectral imagery.

Root-knot nematodes disrupt xylem flow and compromise root nutrient absorption, thereby intensifying nutrient dilution effects and exacerbating chlorophyll degradation. The combination of nutrient limitation and hydric stress may therefore act synergistically, amplifying both spectral and thermal responses measurable by UAV platforms.

These interactions underscore the relevance of incorporating nutritional status into remote sensing-based analyses of biotic stress. Nutrient data provide a critical contextual layer that can help distinguish nematode-induced physiological decline from other stressors that may generate visually or spectrally similar signatures. Future diagnostic frameworks would benefit from integrating foliar nutrient profiles with hyperspectral indices sensitive to pigment composition or red-edge parameters.

Ref. [

34] demonstrated that multispectral remote sensing can effectively identify spectral shifts in coffee associated with both abiotic factors, including nutrient deficiencies, and biotic agents such as

Cercospora coffeicola, emphasizing the importance of differentiating overlapping spectral patterns arising from multiple stressors. Therefore, the incorporation of nutritional information into machine learning or multivariate diagnostic models could enhance classification accuracy and reduce misinterpretation of stress-related reflectance anomalies.

4.5. Implications for Precision Agriculture

Given the increasing availability of low-cost UAV platforms and advances in automated radiometric correction, segmentation, and index extraction pipelines, the approach investigated in this study has strong potential for operational integration into routine farm monitoring [

31,

34]. Modern decision-support systems increasingly rely on multisensor data fusion; thus, the combined use of multispectral, thermal, and textural features identified here aligns with current trends in digital agriculture. Although spectral indices alone may offer useful diagnostic signals, the inclusion of canopy temperature and textural information enhances diagnostic robustness by capturing complementary dimensions of plant stress responses.

The results also demonstrate that texture metrics derived from high-resolution imagery are particularly promising for nematode detection. By quantifying spatial heterogeneity within the canopy, textural parameters can capture morphological changes alongside or that can precede reflectance or temperature shifts. This may be especially advantageous in scenarios where spectral contrast is reduced, such as during the rainy season or in highly vegetative canopies. However, operational deployment requires careful consideration of sensor resolution, illumination geometry, and canopy structure, as these factors directly influence texture computation and reproducibility.

Another important implication is the transferability of the proposed methodology. The diagnostic framework evaluated here, combining spectral, thermal, and textural indicators, can be applied to other nematode-sensitive crops, including soybean, cotton, vegetables, and orchard species. Nevertheless, environmental and phenological variability must be accounted for, as soil moisture, climate conditions, and canopy architecture can affect reflectance and temperature responses. Multi-season and multi-site validation will be essential to calibrate thresholds and ensure the robustness of classification models across diverse agroecosystems.

Overall, the findings presented in this study contribute to the expanding foundation for remote sensing–based diagnostic systems within precision agriculture. By providing initial evidence of spectral, thermal, and structural signatures associated with nematode stress, this work highlights key pathways for the development of early warning systems and spatially explicit management tools. Continued research integrating UAV imaging, machine learning models, and ground-based nematode assessments will be essential for transforming these promising results into operational protocols for nematode detection, monitoring, and mitigation at the farm scale.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of UAV-based multispectral, thermal, and textural imaging for detecting Meloidogyne exigua infestation in coffee (Coffea arabica) plants under field conditions. The integration of canopy temperature, spectral indices, and texture features enabled the identification of alterations associated with nematode stress, even before visible symptoms occurred.

Overall, the results highlight the feasibility of employing UAV-based remote sensing for early, non-destructive diagnosis of root-knot nematodes in coffee. This approach supports the development of precision management strategies that can reduce production losses and contribute to the sustainability of coffee cultivation systems.

Under the conditions of this research, vegetation indices sensitive to greenness, such as GNDVI, showed better correlation values with the number of galls on coffee plants during the dry season, as did NGRDI during the rainy season, demonstrating to be a promising indicator for the early detection of plant-parasitic nematodes. Future work should expand sampling to include multiple fields and incorporate deep learning to evaluate the predictive ability of spectral–thermal–textural combinations.

The findings provide a solid foundation for subsequent large-scale and multitemporal studies.