A Soft Robotic Gripper for Crop Harvesting: Prototyping, Imaging, and Model-Based Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Labor-intensive manual harvesting (wages of $16–18 per hour in the U.S. [7]), rendered unsustainable by demographic shifts.

- Industrial mechanization enhances efficiency for durable crops like grains through precision agriculture technologies (e.g., sensor-based optimization and IoT-enabled monitoring) [8], but exacerbates post-harvest losses in soft fruits due to mechanical damage. For strawberries, for instance, studies indicate that mechanical harvesting and handling can lead to significant bruising and quality degradation, primarily due to compression and impact forces [9,10].

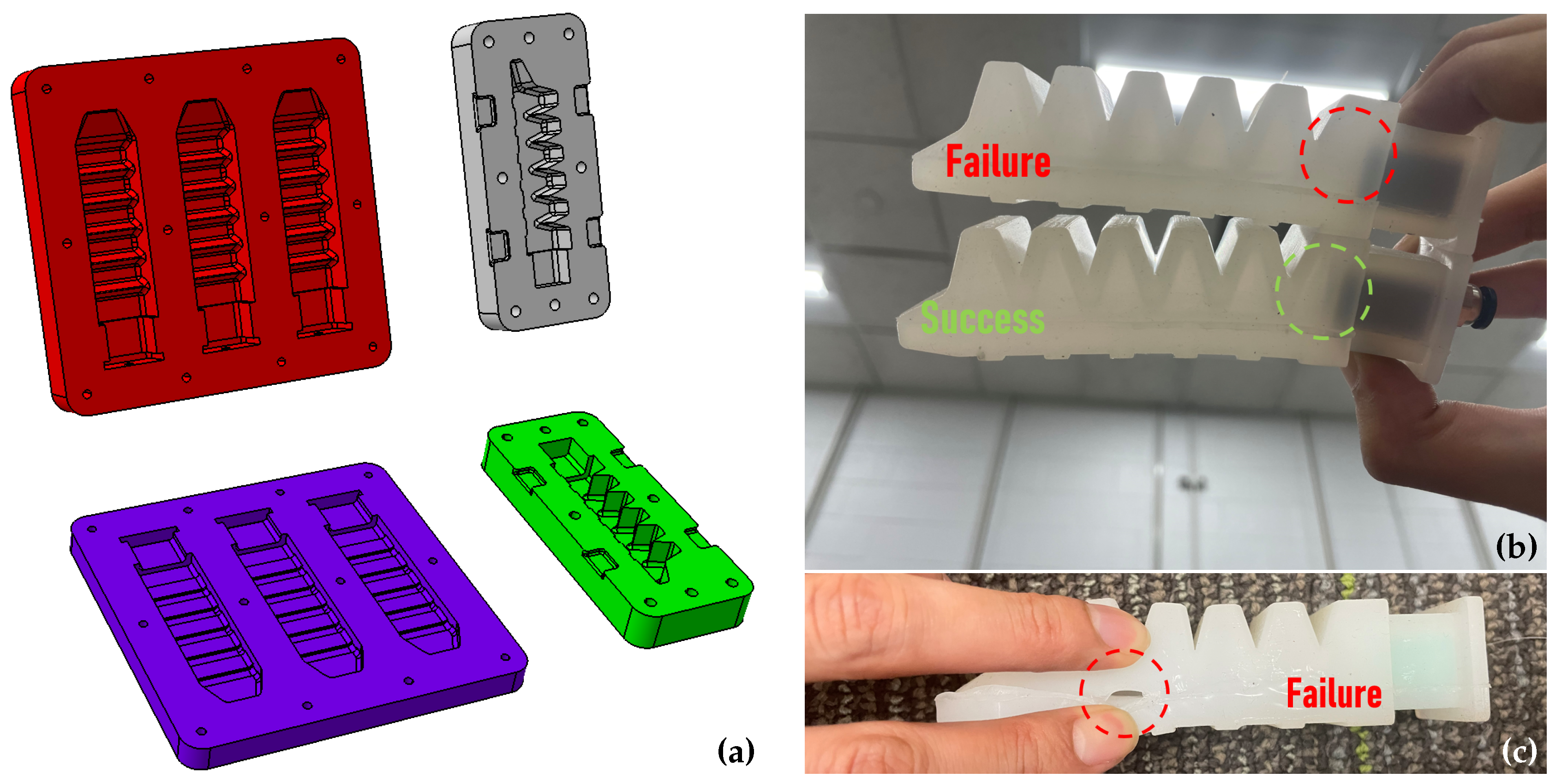

- Low-cost, high-yield fabrication of soft grippers: We propose a novel mold design integrating compressive sealing and bubble displacement mechanisms, enabling rapid, DIY-friendly production of silicone-based soft grippers in 30–40 min per unit. Each finger costs less than $4, representing a cost reduction of over 60% compared to traditional FDM-based 3D-printed molds (typically $10–$12 per finger, including materials and post-processing). Notably, our method has achieved 100% fabrication yield across five independent gripper prototypes without reliance on industrial-grade equipment.

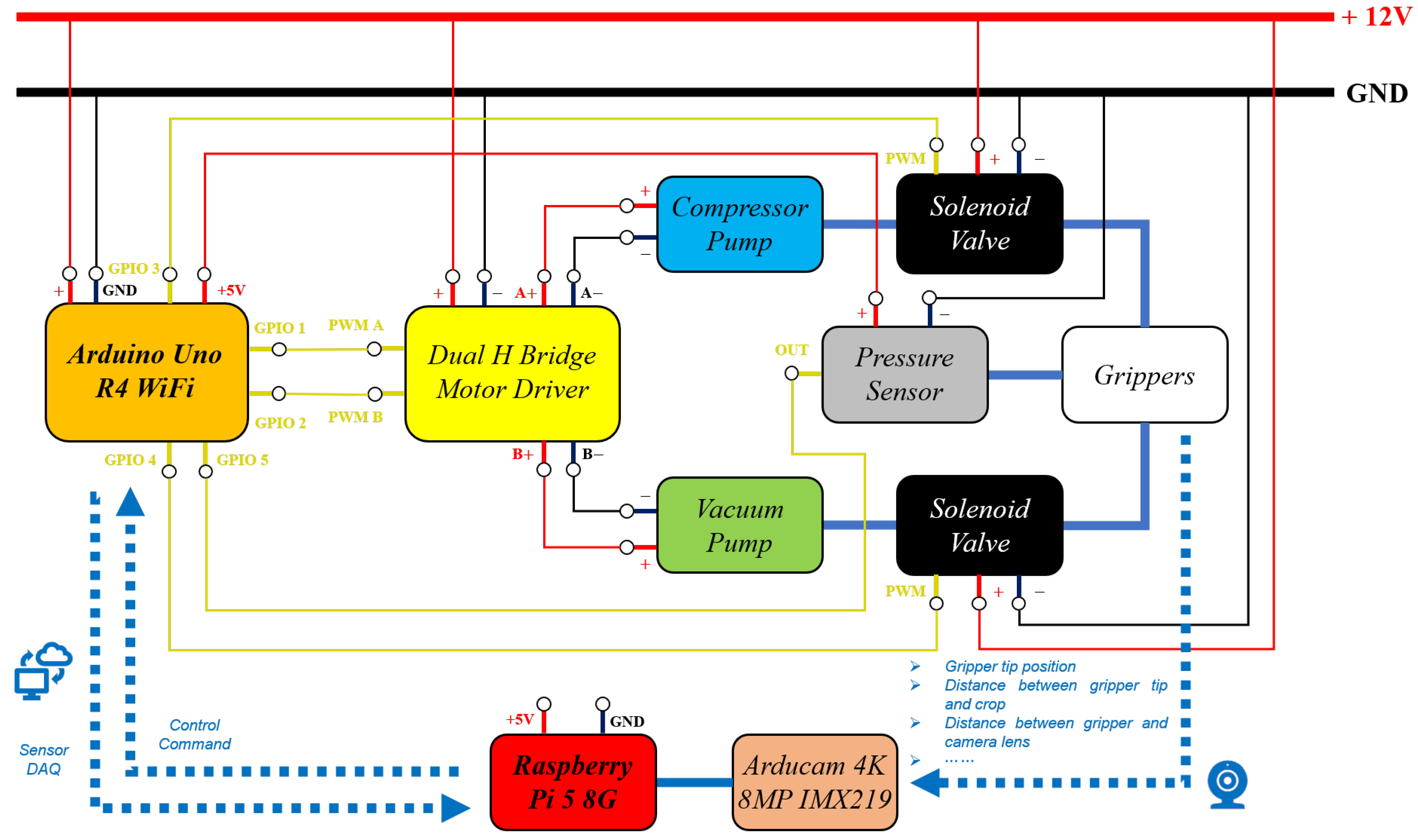

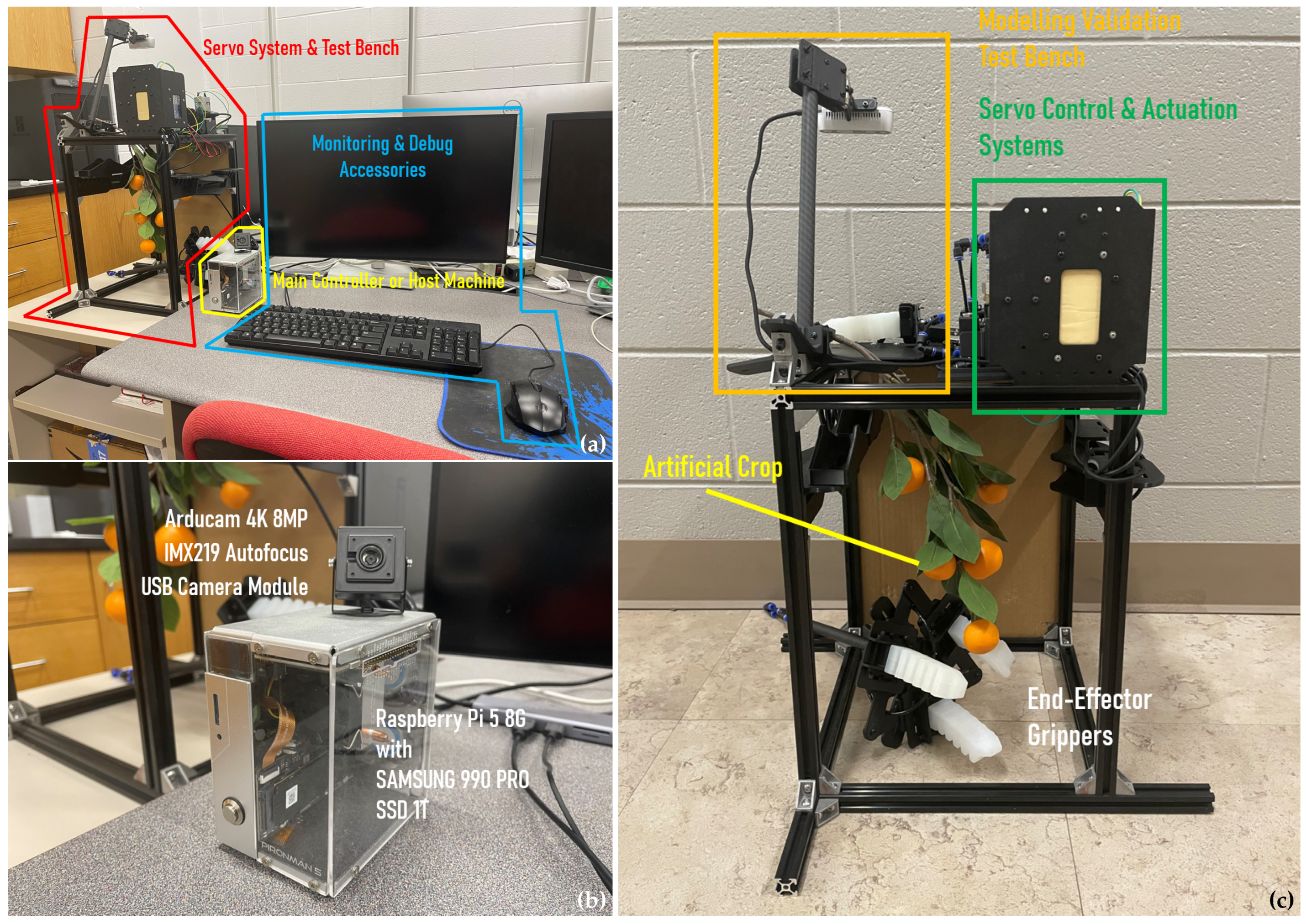

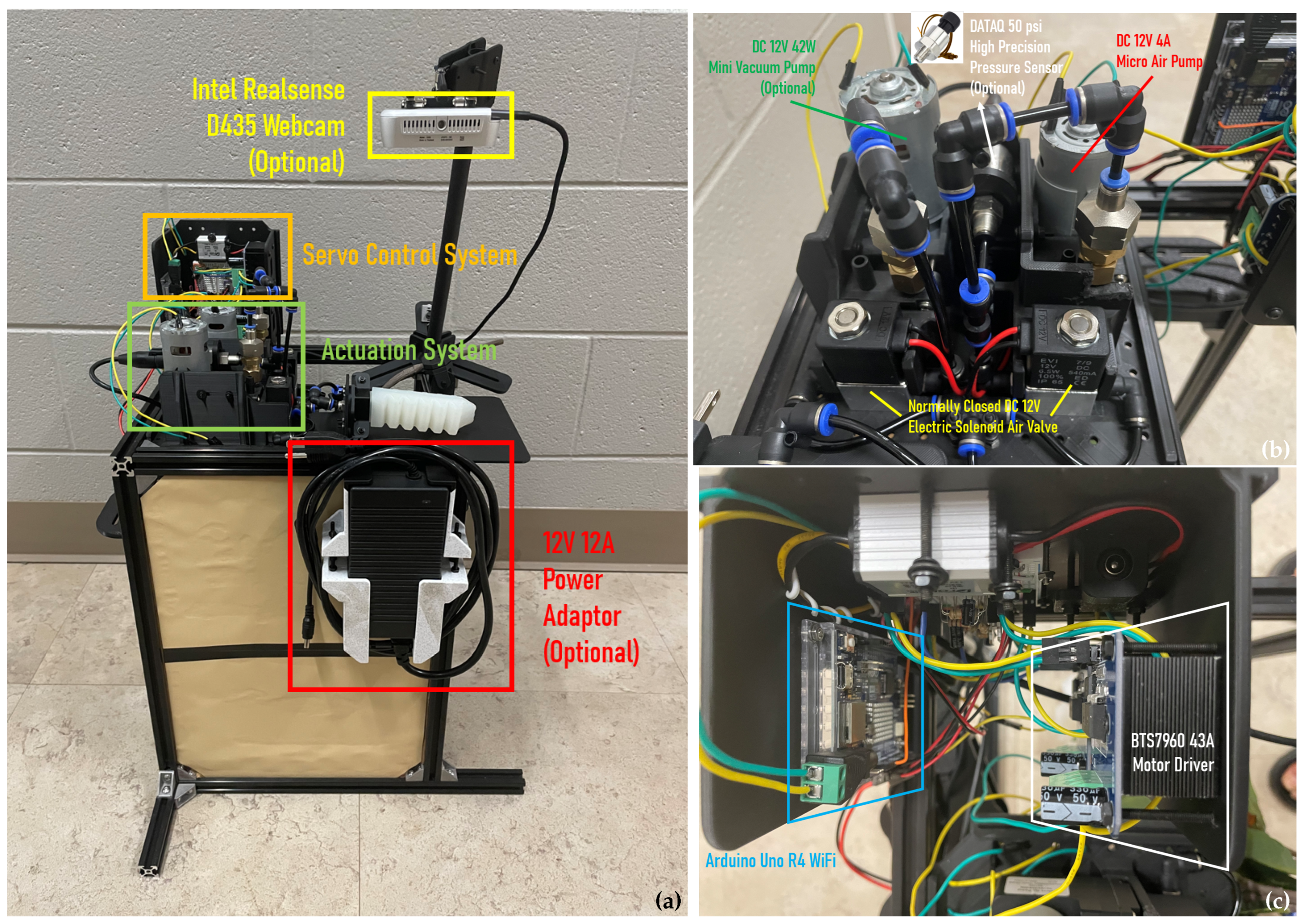

- Cost-effective, IoT-friendly system architecture: Our hardware design adopts decentralized pneumatic control nodes and edge-level visual computing, maintaining real-time responsiveness while significantly reducing system cost. Each pneumatic node costs $172–185, enabling a 50–54% cost reduction compared to commercial deep-learning-based robotic platforms. The compactness and modularity of the system promote easy deployment in field environments and scalability across different crops.

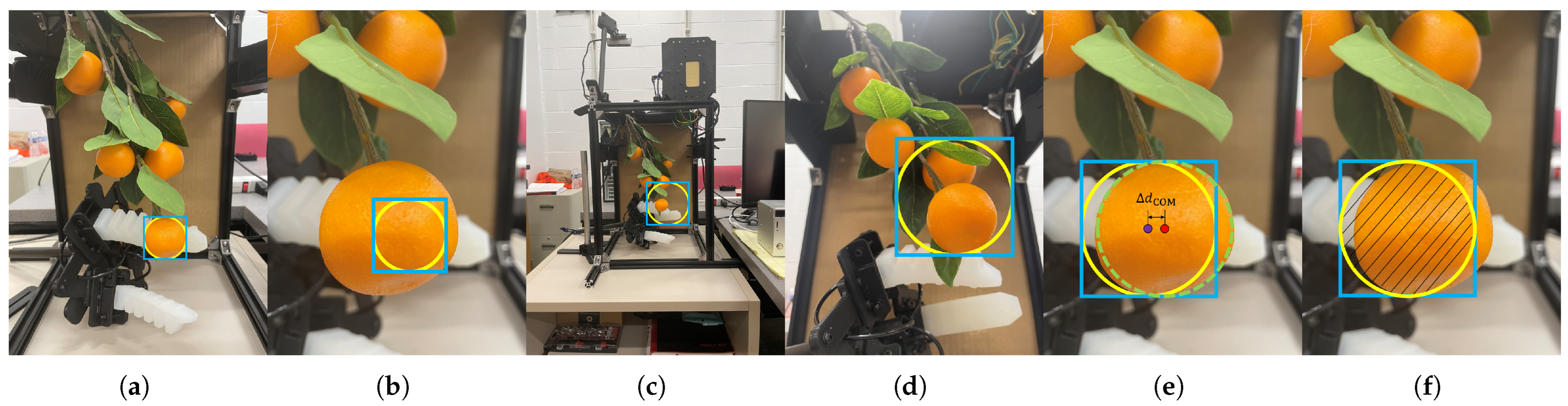

- Lightweight and generalizable vision system for crop and gripper tracking: Instead of relying on deep learning models or color-coded markers, we develop a robust image processing pipeline based on handcrafted geometric and contrast features. This system is capable of:

- Assessing crop maturity, ranking visible candidates based on ripeness scores, and prioritizing targets for sequential harvesting.

- Tracking gripper prototypes of various designs without any visual markers, even during partial occlusion, rapid camera motion, or environmental disturbances in the field (e.g., wind).

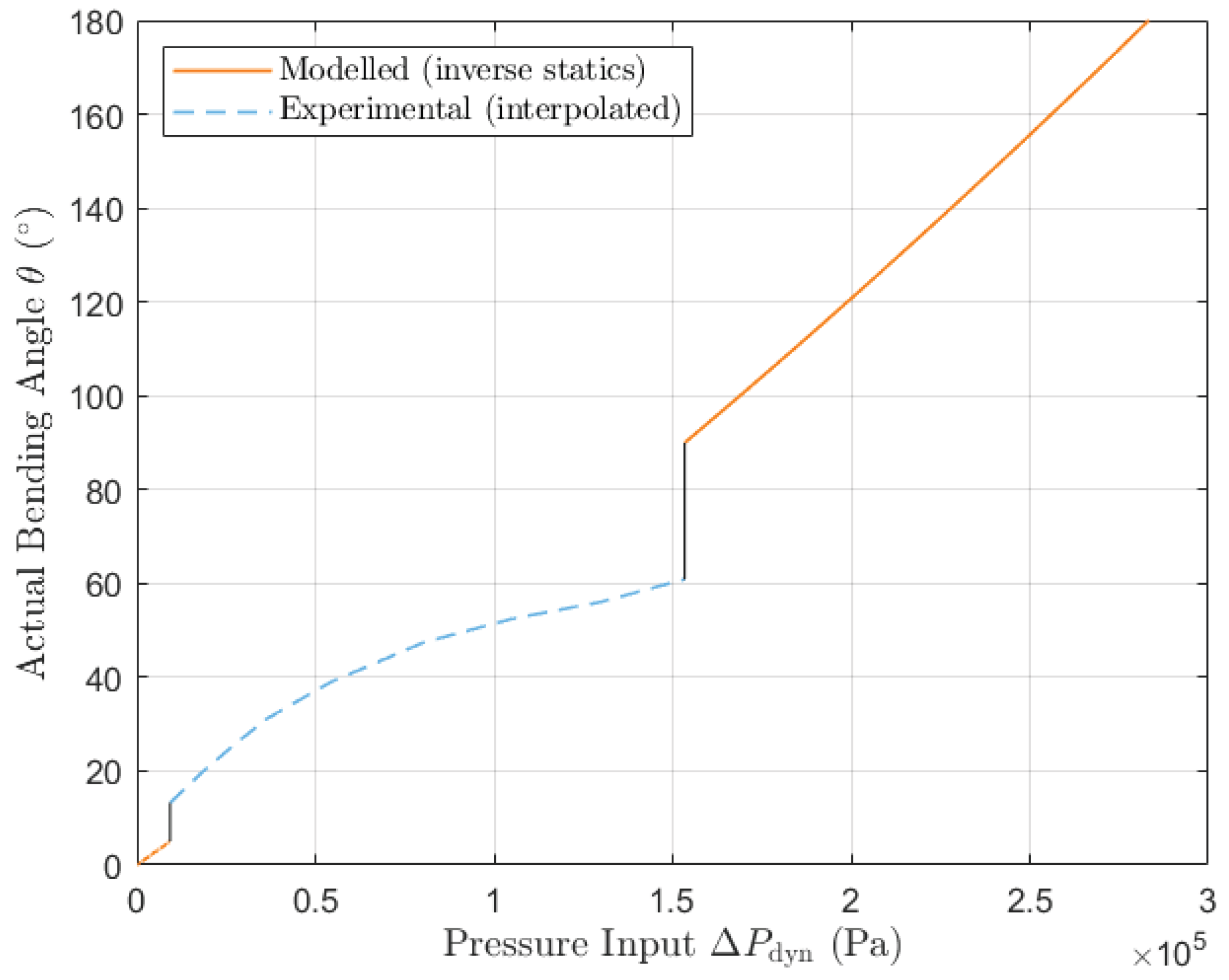

This unified pipeline supports real-time tracking (42–73 fps on Raspberry Pi 5) and maintains spatial consistency across perception and actuation layers—bridging the gap between high-level visual intelligence and low-level control execution. - Accurate and generalized analytical modeling: We introduce a Neo-Hookean-based statics model that accounts for circumferential stress and variable cross-sectional geometry, enabling a more realistic estimation of actuator deformation than the constant-curvature approximation. Experimental measurements validate the theoretical pressure-angle relationship, showing an average relative error (gripper tip position change) below +4.1 mm across bending angles from 0° to 70°. This model serves as the core of a hybrid (feedforward/feedback) controller, enhancing grasp accuracy while reducing reliance on expensive tactile sensors.

2. Related Work

2.1. Robotic Perception and System Architecture in Agriculture

2.2. Soft Robotic Grippers and Actuation Strategies

2.3. Modeling and Sensing for Soft Actuators

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Gripper Prototype Design and Manufacturing

3.1.1. Material Selection

3.1.2. Manufacturing Process

3.1.3. Gripper Mold Design Benchmark

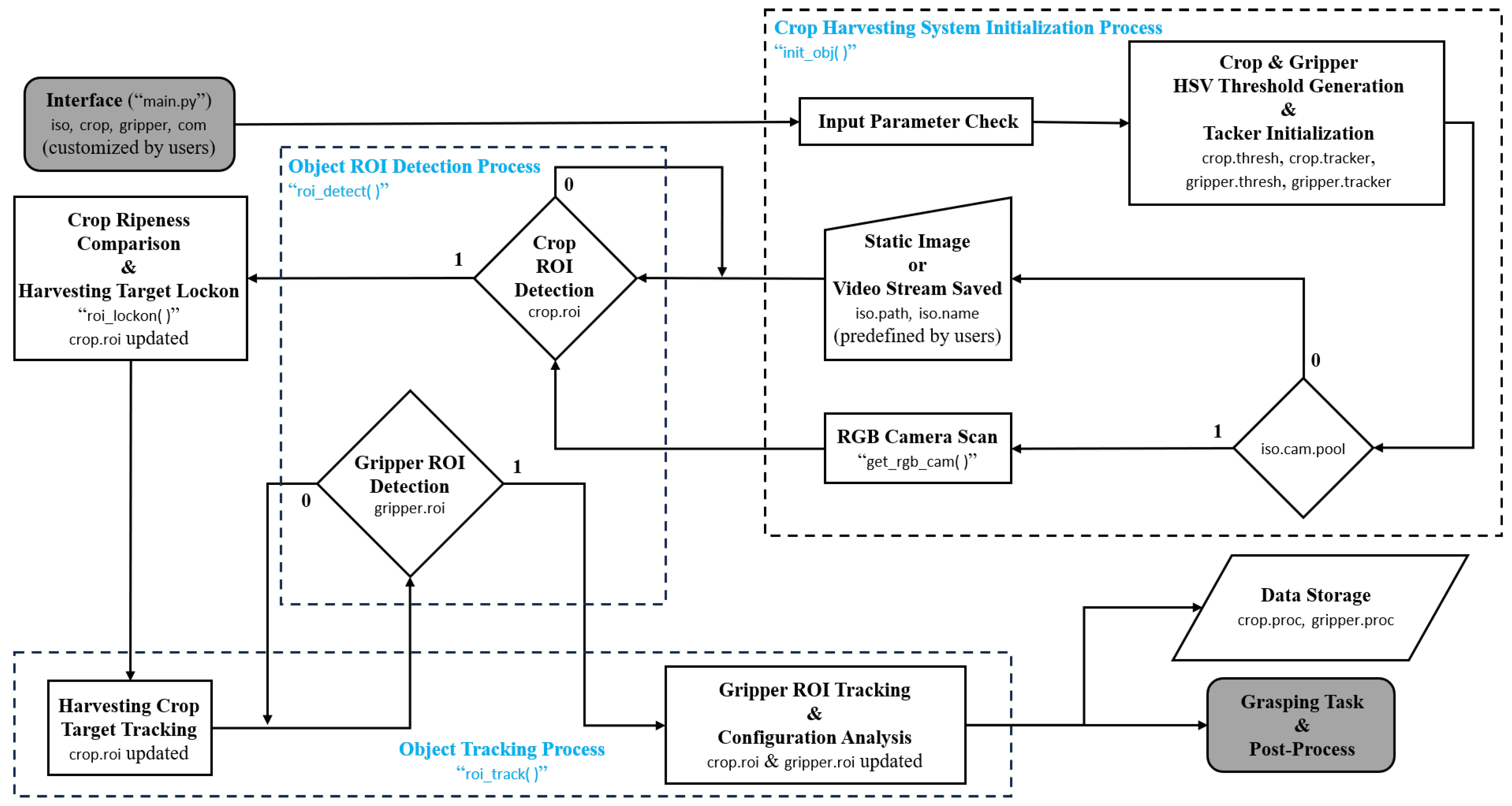

3.2. Crop Harvesting System Architecture

3.3. Reinforced Image Processing

3.3.1. Robust Crop Image Processing & Tracking with Confidence Validation

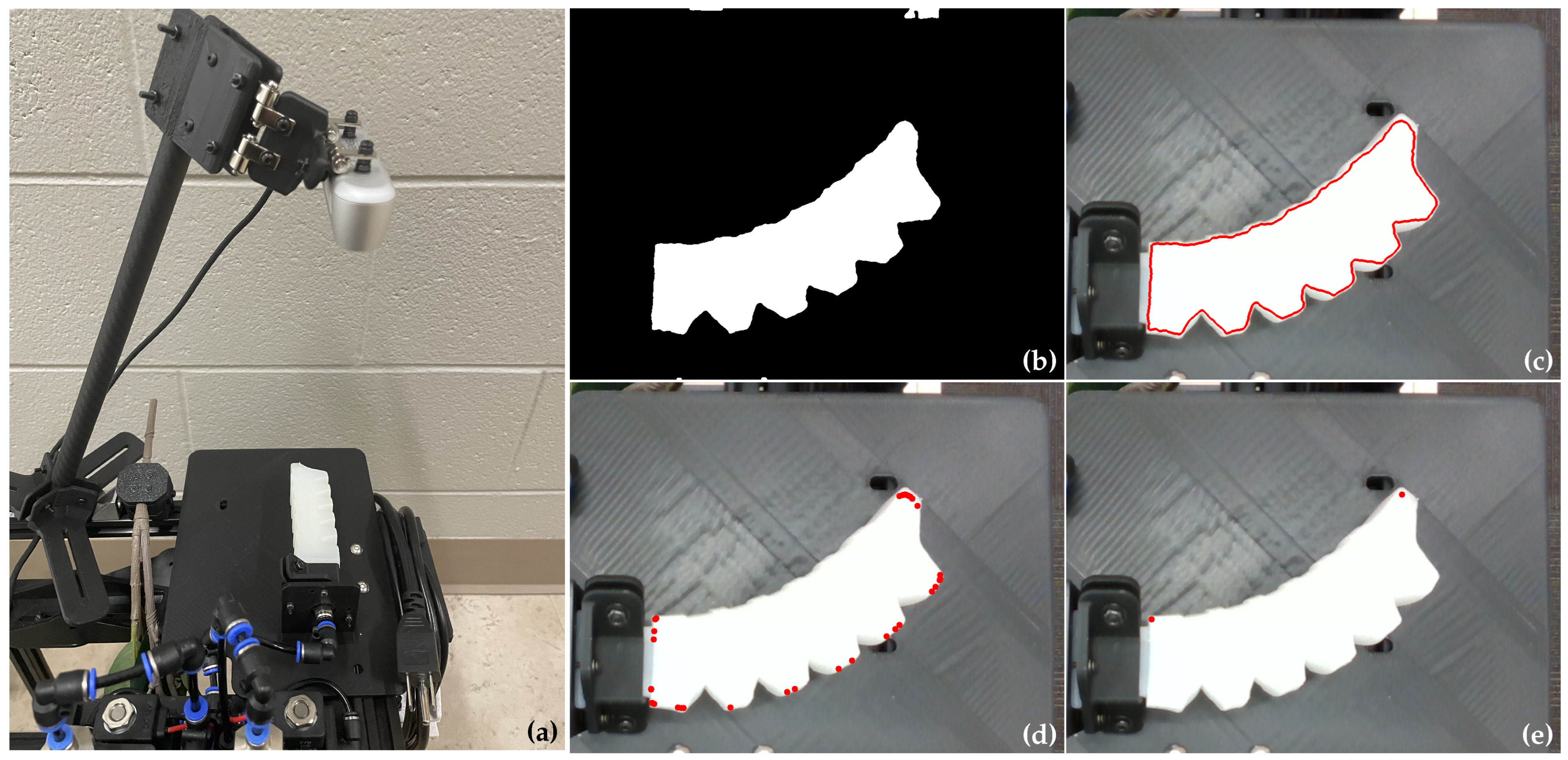

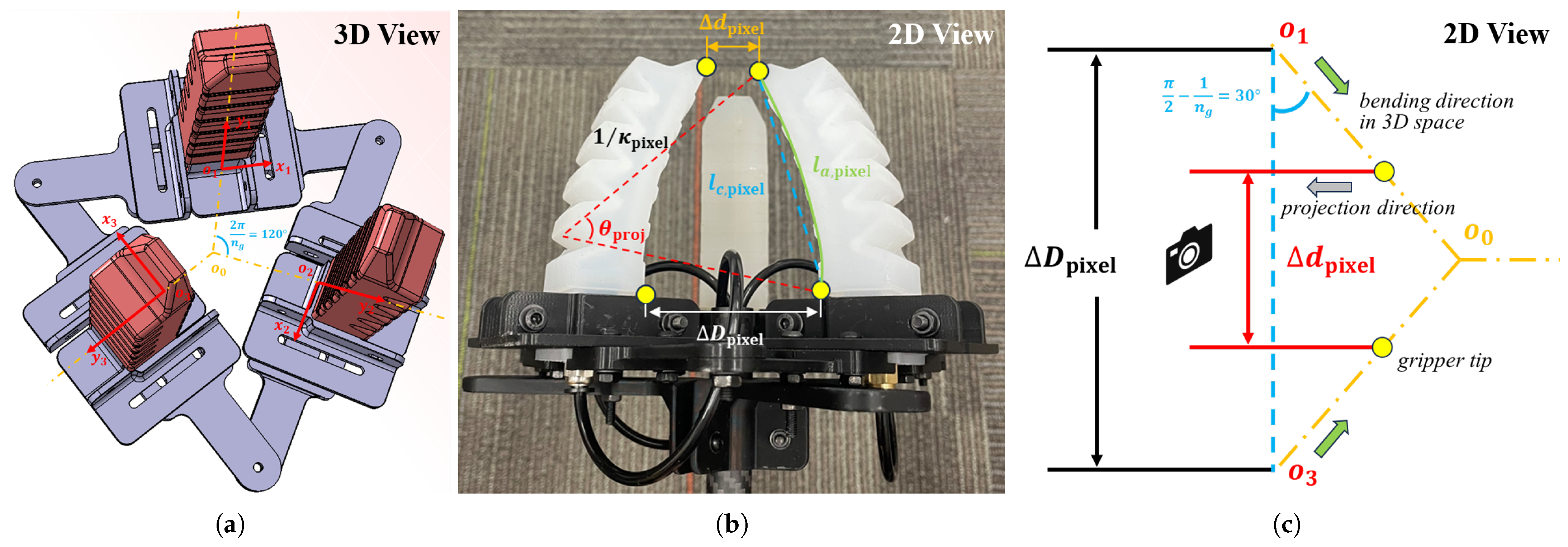

3.3.2. Universal Gripper Feature Detection via Shape Priors

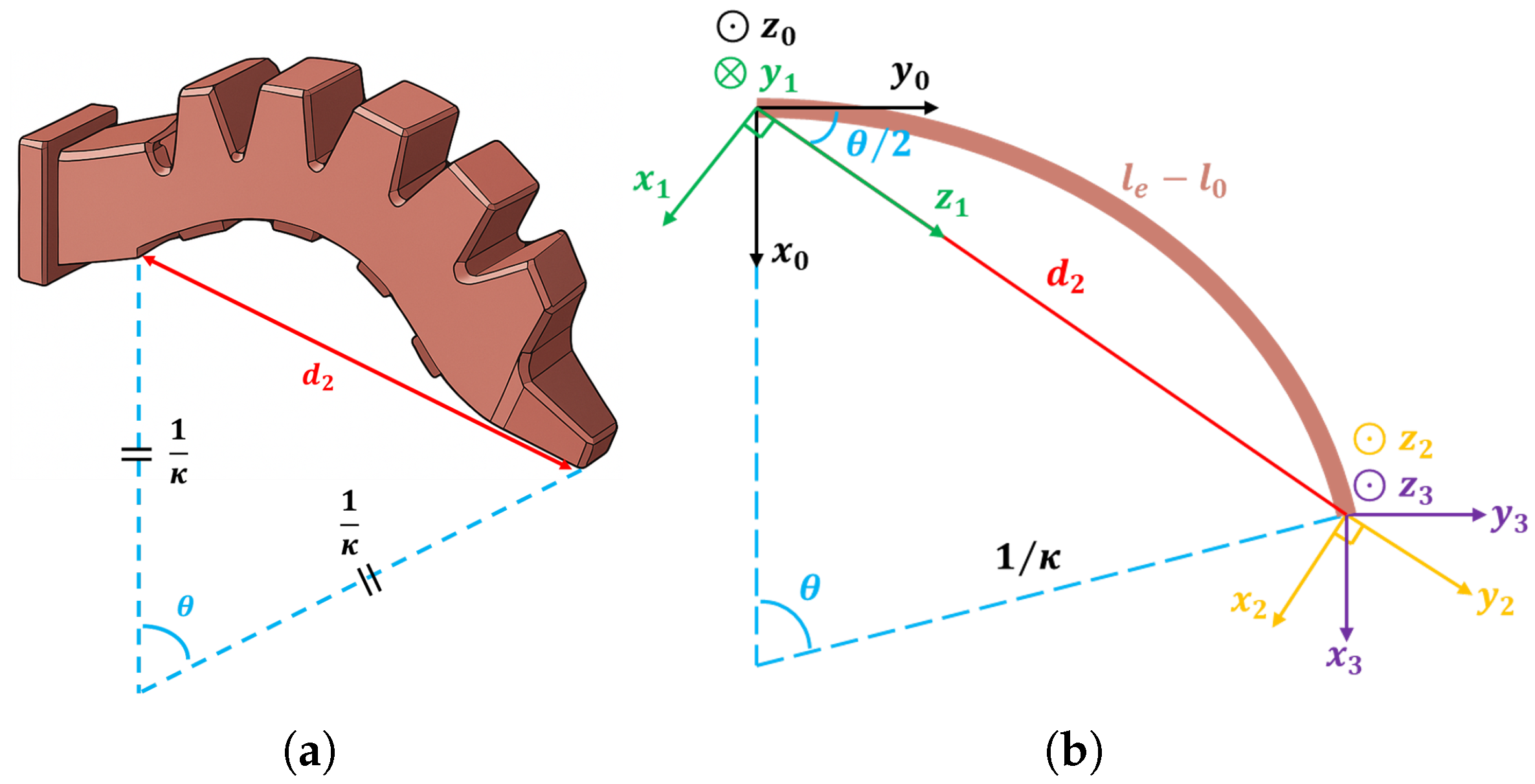

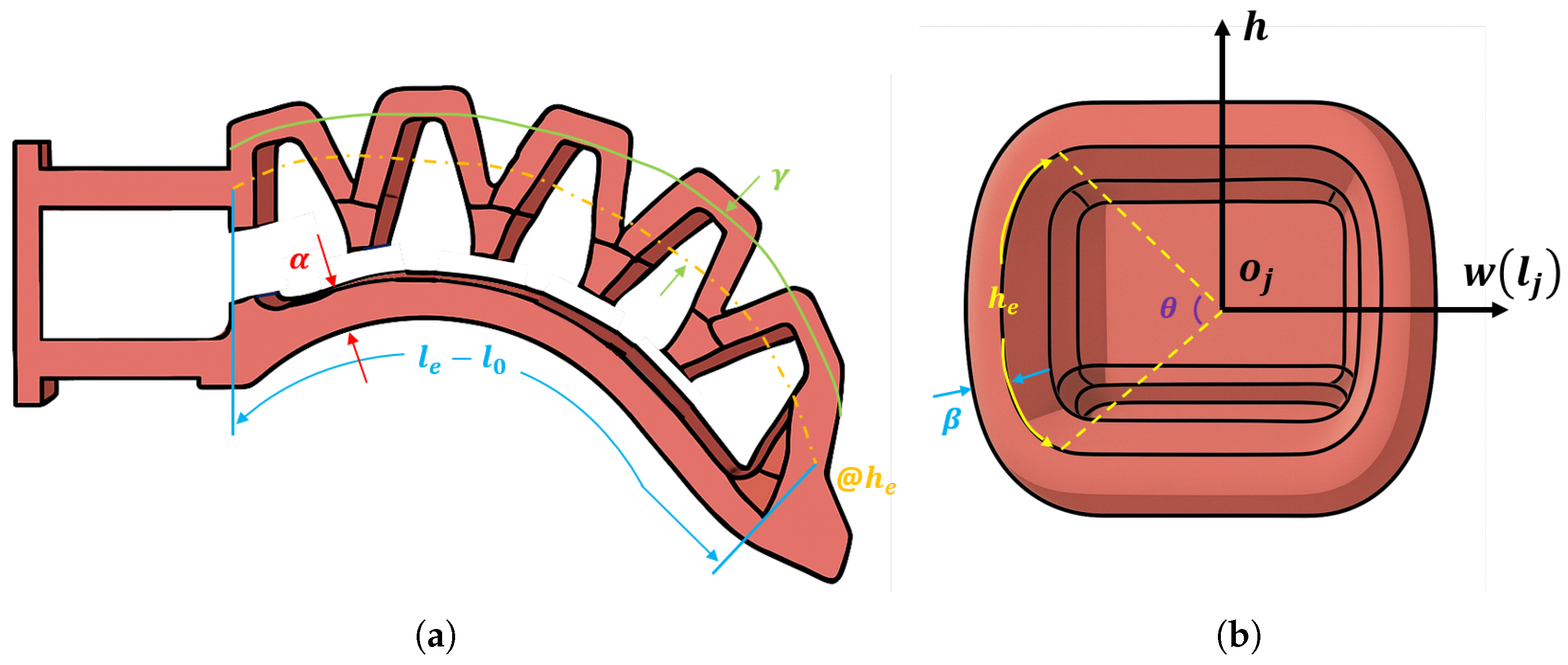

3.4. Gripper Modeling

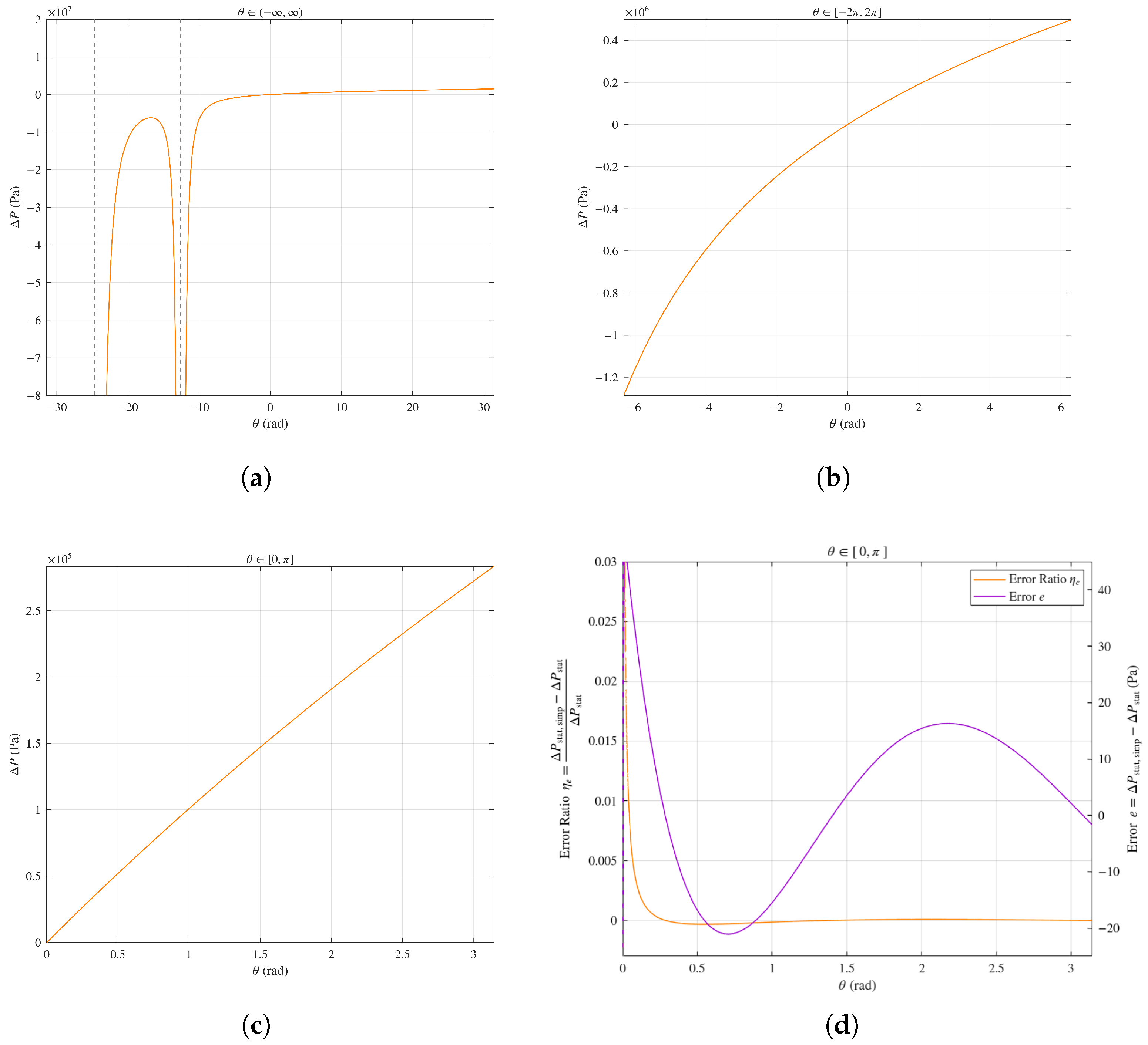

3.4.1. Gripper Static Modeling

3.4.2. Modeling of the Gripper Dynamics

3.4.3. Sensor & Electronics Dynamics

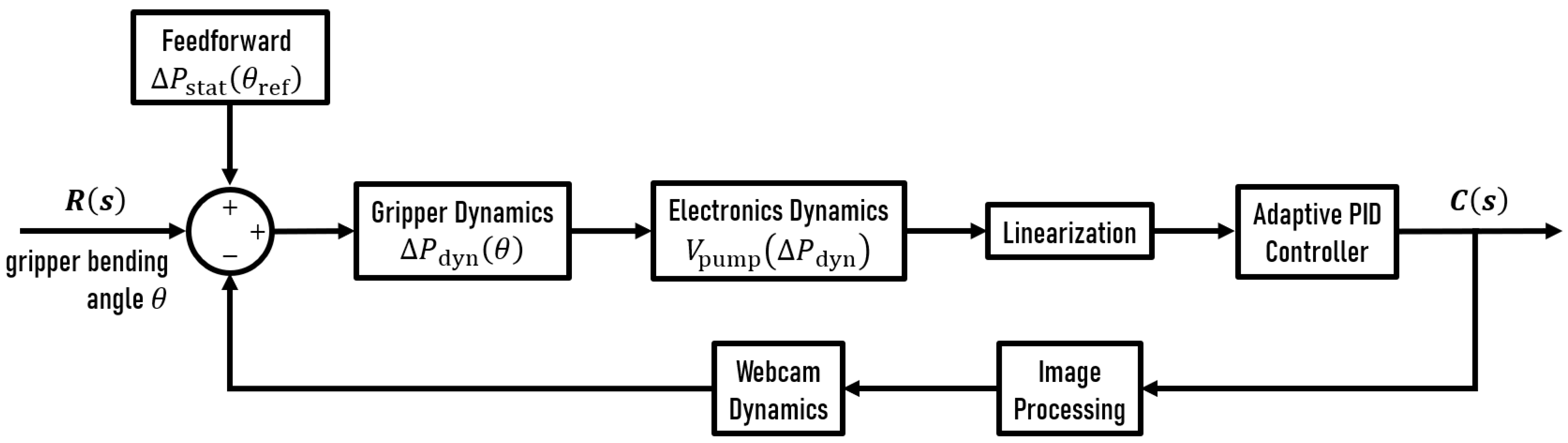

3.5. Controller Design

3.5.1. System Linearization

3.5.2. Tuning of the Controller Gains

- The added pole does not dominate the system’s transient response.

- The resulting third-order characteristic polynomial remains well-conditioned.

- The integral gain can be uniquely solved via pole-matching with the closed-loop system matrix.

4. Results and Discussion

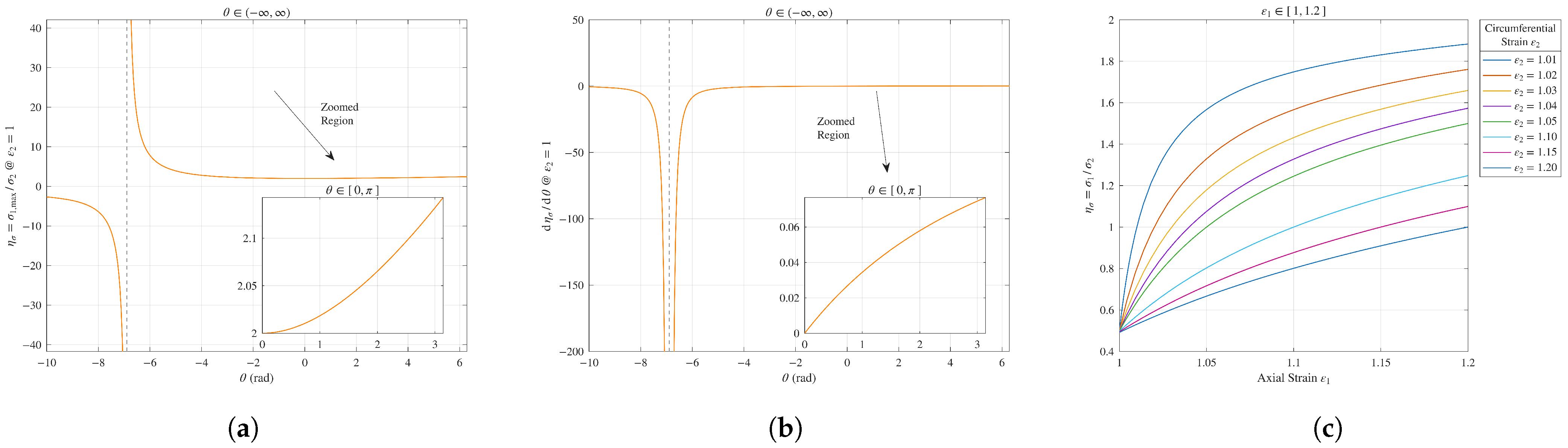

4.1. Examining the Effect of Circumferential Stress

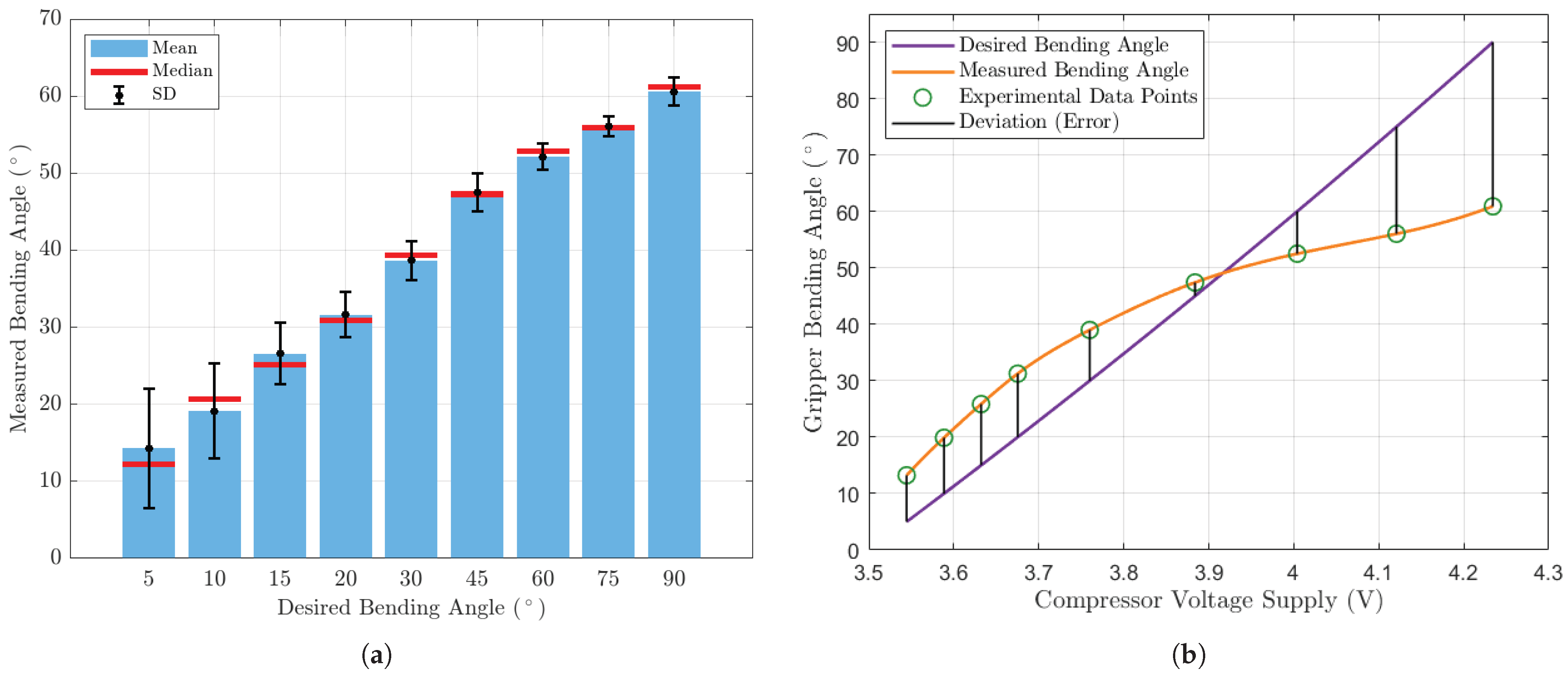

4.2. Gripper Statics Model Verification

4.3. Controller Performance Validation

4.4. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivation of the Neo-Hookean Statics Model

- The stress in the radial direction (which will affect the bottom layer wall thickness) and the strain in circumferential direction (the deformation will not contribute so much to the gripper bending) are negligible.

- The length of the gripper bending towards side always remains unchanged.

- The bending angle of the gripper side layer is deemed to be equivalent to the gripper bending angle (see Figure 17b).

Appendix B. System Software Architecture and Algorithm Implementation

| Algorithm A1 System initialization and multi-module loading (within libpublic and libgpcombind) |

| Require: None Ensure: Initialized system objects: iso, com, crop, gripper Step 1 Dynamic loading of core modules: public function library, communication module, vision processing module. Step 2 Initialize system configuration objects: • iso: System environment configuration (camera parameters, debug flags, Three-Strike Policy) • com: Communication configuration (WiFi/serial parameters, device numbering) • crop: Crop configuration (color thresholds, tracker type) • gripper: Gripper configuration (geometric features, tracking parameters) Step 3 Automatic detection of available RGB cameras and resolution configuration. Step 4 Set color space thresholds (HSV environment colors, crop colors, gripper colors). Step 5 Initialize multi-threading events and lock mechanisms. |

| Algorithm A2 Crop detection and maturity analysis (within gpdipch) |

| Require: Raw image frame (iso.org) Ensure: Candidate crop ROI list (crop.roi) Step 1 Color space conversion: BGR → LAB → HSV. Step 2 Extreme color filtering (white region removal). Step 3 Crop color protection segmentation: • Apply crop-specific HSV thresholds. • Soil color masking to eliminate interference. Step 4 Morphological processing and contour analysis: • Otsu threshold segmentation. • Minimum enclosing circle fitting. Step 5 Maturity validation: • Calculate mature color pixel ratio. • Apply maturity threshold filtering (default 80%). Step 6 Spatial constraint validation: • Boundary distance checking. • Size rationality verification. Control Logic: if No valid contours detected: return Empty ROI list else: for Each detected contour: if Contour area < Minimum threshold or > Maximum threshold: Skip contour else: Calculate maturity ratio if Maturity ratio ≥ Threshold: Add to candidate list else: Skip contour end for return Sorted candidate list (largest to smallest) |

| Algorithm A3 Gripper detection and geometric feature extraction (within gpdipch) |

| Require: Raw image frame (iso.org) Ensure: Gripper key vertex coordinates (gripper.roi) Step 1 Multi-level masking: • Inverse crop color masking • Leaf color exclusion • Gripper white region enhancement Step 2 Geometric constraint filtering: • Rectangularity verification (golden ratio constraint) • Edge distance constraint • Parallelism verification (angle tolerance ±10°) Step 3 Hierarchical contour analysis: • Gaussian blur and Otsu segmentation • Minimum area rectangle fitting • Convex hull vertex extraction Step 4 Key vertex refinement: • Angle threshold filtering (1°–2° redundancy elimination) • Tip/base classification • Bending angle calculation Control Logic: while Processing contours: if Contour area < Minimum threshold: Skip contour else: Calculate width-to-height ratio if Ratio not within golden ratio tolerance: Skip contour else: Check edge proximity if Too close to image border: Skip contour else: Calculate inclination angles if Angles not within parallel tolerance: Skip contour else: Add to valid gripper list end while if Valid grippers found: Select best candidates based on size consistency Extract key vertices using angle-based filtering else: return Empty vertex list |

| Algorithm A4 Multi-target tracking and state management (within gpdipch) |

| Require: Detected ROI, image sequence Ensure: Real-time tracking status Step 1 Tracker selection and initialization: • Support for multiple algorithms (CSRT, KCF, MedianFlow) • Dynamic selection based on system resources (MedianFlow default) Step 2 Dual verification mechanism: • Primary region: Circular maturity verification • Secondary region: Non-shadowed area color verification Step 3 Scale adaptation: • Depth axis motion compensation • Dynamic bounding box adjustment Step 4 Occlusion handling: • Temporary target loss tolerance • Trajectory prediction and reacquisition Control Logic: while Tracking active: Update tracker with current frame if Tracking successful: Extract new bounding box Apply dual verification: Primary: Calculate mature pixels in circular region Secondary: Calculate mature pixels in rectangular complement if Both verifications pass: Update ROI position Continue tracking else: if Consecutive failures > Threshold: Reinitialize tracker else: Continue with predicted position else: if Target lost for extended period: Terminate tracking thread to save resources Return to detection mode (Algorithm A2) else: Predict position based on motion model end while |

| Algorithm A5 Vision-actuation thread control, parallel processing and resource management |

| Require: Image stream, control commands Ensure: Coordinated vision-actuation loop Step 1 Thread initialization hierarchy: • Primary: Crop processing thread (dip_crop) • Secondary: Gripper processing thread (dip_gripper) • Tertiary: Communication processing thread (RX_UDP/RX_serial) Step 2 Event-driven synchronization: • Image capture event triggers all processing threads • Mutex locks protect shared image data and ROI parameters • Threads operate asynchronously with coordinated timing Step 3 Adaptive resource management: • Dynamic priority adjustment based on detection success rates • Graceful degradation under poor detection conditions • Efficient thread termination and resource cleanup Thread Control Logic: 1. Crop Processing Thread while System running: Wait for crop detection event Acquire processing lock if No crop detected: Perform crop detection if Detection successful: Initialize tracker else: Update tracking if Tracking failed: Reset detection Release processing lock Clear crop detection event end while 2. Gripper Processing Thread while System running: Wait for gripper detection event Acquire processing lock if No gripper detected: Perform gripper detection if Detection successful: Lock on gripper else: if not Aligned with crop: Perform tracking else: Perform precise vertex detection Release processing lock Clear gripper detection event end while Resource Optimization: • Monitor detection success rates continuously • Reduce processing frequency for failing modules • Reallocate resources to higher-success components • Enter low-power mode during persistent failures |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- New American Economy. A Vanishing Breed: How the Decline in U.S. Farm Laborers Over the Last Decade Has Hurt the U.S. Economy and Slowed Production on American Farms. Available online: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/research/vanishing-breed-decline-u-s-farm-laborers-last-decade-hurt-u-s-economy-slowed-production-american-farms (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Eurostat. Farms and Farmland in the European Union—Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Farms_and_farmland_in_the_European_Union_-_statistics (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- International Labour Organization. Asia-Pacific Sectoral Labour Market Profile: Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/brief/asia-pacific-sectoral-labour-market-profile-agriculture (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- FoodBev Media. Berry Big Problem: What’s Spoiling Our Strawberries? Available online: https://www.foodbev.com/news/berry-big-problem-what-s-spoiling-our-strawberries (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- USDA Economic Research Service. Farm Labor. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Getahun, S.; Kefale, H.; Gelaye, Y. Application of Precision Agriculture Technologies for Sustainable Crop Production and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 2126734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliasgarian, S.; Ghassemzadeh, H.R.; Moghaddam, M.; Ghaffari, H. Mechanical Damage of Strawberry During Harvest and Postharvest Operations. Acta Technol. Agric. 2015, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Ejaz, S.; Rehman, R.N.U.; Khan, M.; Qadri, R. Postharvest Quality Management of Strawberries. In Strawberry—Pre- and Post-Harvest Management Techniques for Higher Fruit Quality; Asao, T., Asaduzzaman, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Khanal, S.R.; Zhang, X.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q. Real-time Strawberry Detection Based on Improved YOLOv5s Architecture for Robotic Harvesting in Open-Field Environment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.03998. [Google Scholar]

- Botta, A.; Cavallone, P.; Baglieri, L.; Colucci, G.; Tagliavini, L.; Quaglia, G. A Review of Robots, Perception, and Tasks in Precision Agriculture. Appl. Mech. 2022, 3, 830–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, M.; Patle, B.; Mahindrakar, A. Application of AI Techniques and Robotics in Agriculture: A Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics in Agriculture, London, UK, 14–15 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- LattePanda. Running YOLOv8 on LattePanda Mu: Performance Benchmarks. Available online: https://www.lattepanda.com/blog-323173.html (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Navas, E.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Dworak, V.; Weltzien, C.; Fernández, R. Soft gripper for small fruits harvesting and pick and place operations. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 10, 1330496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, H. Application of Soft Grippers in the Field of Agricultural Harvesting: A Review. Machines 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintake, J.; Rosset, S.; Schubert, B.; Floreano, D.; Shea, H. Versatile Soft Grippers with Intrinsic Electroadhesion Based on Multifunctional Polymer Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, E.; Fernández, R.; Sepúlveda, D.; Armada, M.; González-de Santos, P. Soft Grippers for Automatic Crop Harvesting: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, H.; Zhou, H.; Au, W.; Wang, M.Y.; Chen, C.H. Development and Evaluation of a Robust Soft Robotic Gripper for Apple Harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Maselli, M.; Laschi, C.; Cianchetti, M. Actuation Technologies for Soft Robot Grippers and Manipulators: A Review. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, J.A.; Copaci, D.; del Cerro, D.S.; Moreno, L.; Blanco, D. Efficiency Analysis of SMA-Based Actuators: Possibilities of Configuration According to the Application. Actuators 2021, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cao, W. 3D-Printed Hydraulic Fluidic Logic Circuitry for Soft Robots. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.16827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Zidek, T.; Harbel, C.; Yoon, S.; Strickland, F.S.; Kumar, S.; Shin, M. Soft Robotics: A Review of Recent Developments of Pneumatic Soft Actuators. Actuators 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.C.Y.; Li, M.; Kang, S.; Luo, L.; Yu, H. Reconfigurable, Transformable Soft Pneumatic Actuator with Tunable 3D Deformations for Dexterous Soft Robotics Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.03032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Duan, W. Theoretical modelling of soft robotic gripper with bioinspired fibrillar adhesives. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2022, 29, 2250–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polygerinos, P.; Wang, Z.; Overvelde, J.T.; Galloway, K.C.; Wood, R.J.; Bertoldi, K.; Walsh, C.J. Modeling of soft fiber-reinforced bending actuators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ni, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, W. Hybrid vision/force control of soft robot based on a deformation model. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2019, 29, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chepinskiy, S.A.; Wang, J.; Zhilenkov, A.A.; Krasnov, A.Y.; Chernyi, S. Position control of cable-driven robotic soft arm based on deep reinforcement learning. Information 2020, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Chang, C.; An, W.; Yu, S. A wearable capacitive friction force sensor for E-skin. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 3841–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zuo, R.; Ying, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. A sensory soft robotic gripper capable of learning-based object recognition and force-controlled grasping. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 21, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, F.; Castellini, F.; Muradore, R. A soft, sensorized gripper for delicate harvesting of small fruits. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekscan, Inc. Force and Pressure Sensors. Available online: https://www.tekscan.com/products-solutions/sensors (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Tekscan, Inc. Model 5027—Pressure Mapping Sensor. Available online: https://www.tekscan.com/products-solutions/pressure-mapping-sensors/5027 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Apples—SNAP-Ed Connection. Available online: https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/resources/nutrition-education-materials/seasonal-produce-guide/apples (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Oranges—SNAP-Ed Connection. Available online: https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/resources/nutrition-education-materials/seasonal-produce-guide/oranges (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Peaches—SNAP-Ed Connection. Available online: https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/resources/nutrition-education-materials/seasonal-produce-guide/peaches (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Sadati, S.H.; Naghibi, S.E.; Shiva, A.; Michael, B.; Renson, L.; Howard, M.; Rucker, C.D.; Althoefer, K.; Nanayakkara, T.; Zschaler, S.; et al. TMTDyn: A Matlab package for modeling and control of hybrid rigid–continuum robots based on discretized lumped systems and reduced-order models. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2021, 40, 296–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wagner, J.; Frazelle, C.G.; Walker, I.D. Continuum robot control based on virtual discrete-jointed robot models. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018—44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 October 2018; pp. 2508–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Frazelle, C.G.; Wagner, J.R.; Walker, I.D. Dynamic control of multisection three-dimensional continuum manipulators based on virtual discrete-jointed robot models. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2020, 26, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Computational Continuum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Chapters 4–5. [Google Scholar]

| Model + Algorithm | Resolution (Pixels) | Raspberry Pi Module | Detect Obj. No. (Fps) | Detect + Track Obj. No. (Fps) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| YOLOv5n + SORT | 640 × 640 | Pi 4 | ∼1.5–2.5 | ∼1–2 | ∼1–2 | ∼1 |

| Pi 5 | 4–6 | ∼3.5–5 | 3–4 | ∼2–3 | ||

| YOLOv8n + ByteTrack | 640 × 640 | Pi 4 | ∼2.5–3 | ∼1.5–2 | ∼2–3 | ∼1.5–2 |

| Pi 5 | 8–10 | ∼6–8 | ∼7–9 | ∼5–7 | ||

| MobileNet-SSD + SORT | 300 × 300 | Pi 4 | 8–10 | ∼6–8 | ∼7–9 | ∼6–7 |

| Pi 5 | 15–18 | ∼12–15 | ∼14–16 | ∼12–14 | ||

| YOLOv5n + DeepSORT | 640 × 640 | Pi 4 | ∼1.5–2.5 | ∼0.5–1 | ∼1 | ∼0.5–1 |

| Pi 5 | 4–6 | ∼1–2 | ∼3–4 | ∼1–2 | ||

| Tiny-YOLOv4 + SORT | 416 × 416 | Pi 4 | 3–5 | ∼2–4 | ∼3–4 | ∼2–3 |

| Pi 5 | 10–14 | ∼8–12 | ∼9–11 | ∼7–9 | ||

| YOLOv8s + Hailo-8L | 640 × 640 | Pi 5 | ∼120 | ∼100 | ∼115 | ∼100 |

| Architecture | Device/Item/Material | Price Each ($) 1 | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host | Raspberry Pi 5 8G | 89.97 | 1 |

| SAMSUNG 990 PRO SSD 1T | 159.99 | 1 | |

| Arducam 4K 8MP IMX219 Autofocus USB Camera Module | 38.99 | 1 | |

| Servo | Arduino Uno R4 WiFi | 27.50 | 1 |

| DC 12 V 4 A Micro Air Pump | 45.57 | 1 | |

| Beduan 2 Way Normally Closed DC 12V Electric Solenoid Air Valve | 9.99 | 1 | |

| BTS7960 DC Motor Driver | 7.44 | 1 | |

| Gripper Mold & Accessories 2 | 19.99 | 1 | |

| Gripper Finger 3 | 3.90 | 3 | |

| Node 4 | 184.68 | ||

| 172.18 |

| Link No. i | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gripper Bending Angle (°) | Gripper Finger Tip Distance * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference / Desired | Measured | Reference / Desired | Measured | Error |

| 5 | 13.234 | 3.263 | 8.603 | +5.340 |

| 10 | 19.888 | 6.512 | 12.855 | +6.343 |

| 15 | 25.853 | 9.738 | 16.596 | +6.858 |

| 20 | 31.247 | 12.927 | 19.902 | +6.975 |

| 30 | 38.989 | 19.144 | 24.490 | +5.345 |

| 45 | 47.400 | 27.902 | 29.224 | +1.322 |

| 60 | 52.495 | 35.724 | 31.944 | −3.780 |

| 75 | 56.031 | 42.365 | 33.760 | −8.605 |

| 90 | 60.900 | 47.632 | 36.158 | −11.474 |

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per node | $172–$185 | Based on Bill of Materials (Table 2) |

| Vision processing speed | 42 fps to 73 fps | On Raspberry Pi 5 hardware |

| Gripper fabrication yield | 100% | Across five independent prototypes |

| Fabrication cost reduction | >60% | Compared to traditional 3D-printed molds |

| Mean tip position error | For bending angles – | |

| Maximum tip position error | For bending angles – | |

| Model bending angle error | ∼6.3° | At mid-voltage range (– ) |

| Fabrication time | 30 min to 40 min | Per gripper finger unit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Mohammadpour Velni, J. A Soft Robotic Gripper for Crop Harvesting: Prototyping, Imaging, and Model-Based Control. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110378

Jiang Y, Mohammadpour Velni J. A Soft Robotic Gripper for Crop Harvesting: Prototyping, Imaging, and Model-Based Control. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(11):378. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110378

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yalun, and Javad Mohammadpour Velni. 2025. "A Soft Robotic Gripper for Crop Harvesting: Prototyping, Imaging, and Model-Based Control" AgriEngineering 7, no. 11: 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110378

APA StyleJiang, Y., & Mohammadpour Velni, J. (2025). A Soft Robotic Gripper for Crop Harvesting: Prototyping, Imaging, and Model-Based Control. AgriEngineering, 7(11), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110378