Wearable Sensors to Estimate Outdoor Air Quality of the City of Turin (NW Italy) in an IoT Context: A GIS-Mapped Representation of Diffused Data Recorded over One Year of Monitoring

Highlights

- The use of wearable sensors at human height helps to obtain a picture of urban air pollution that can be used to define environmental scenarios and guide changes to improve liveability.

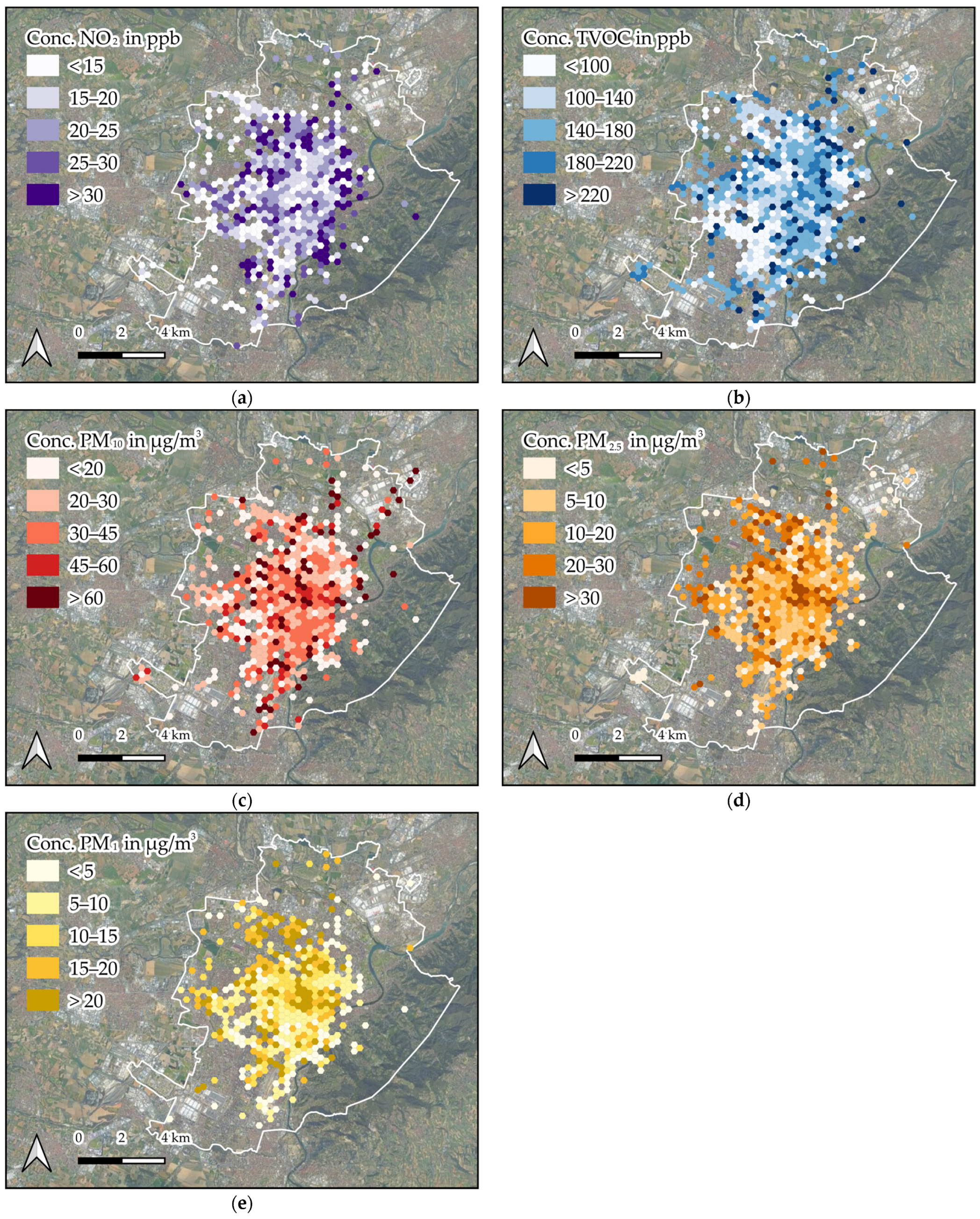

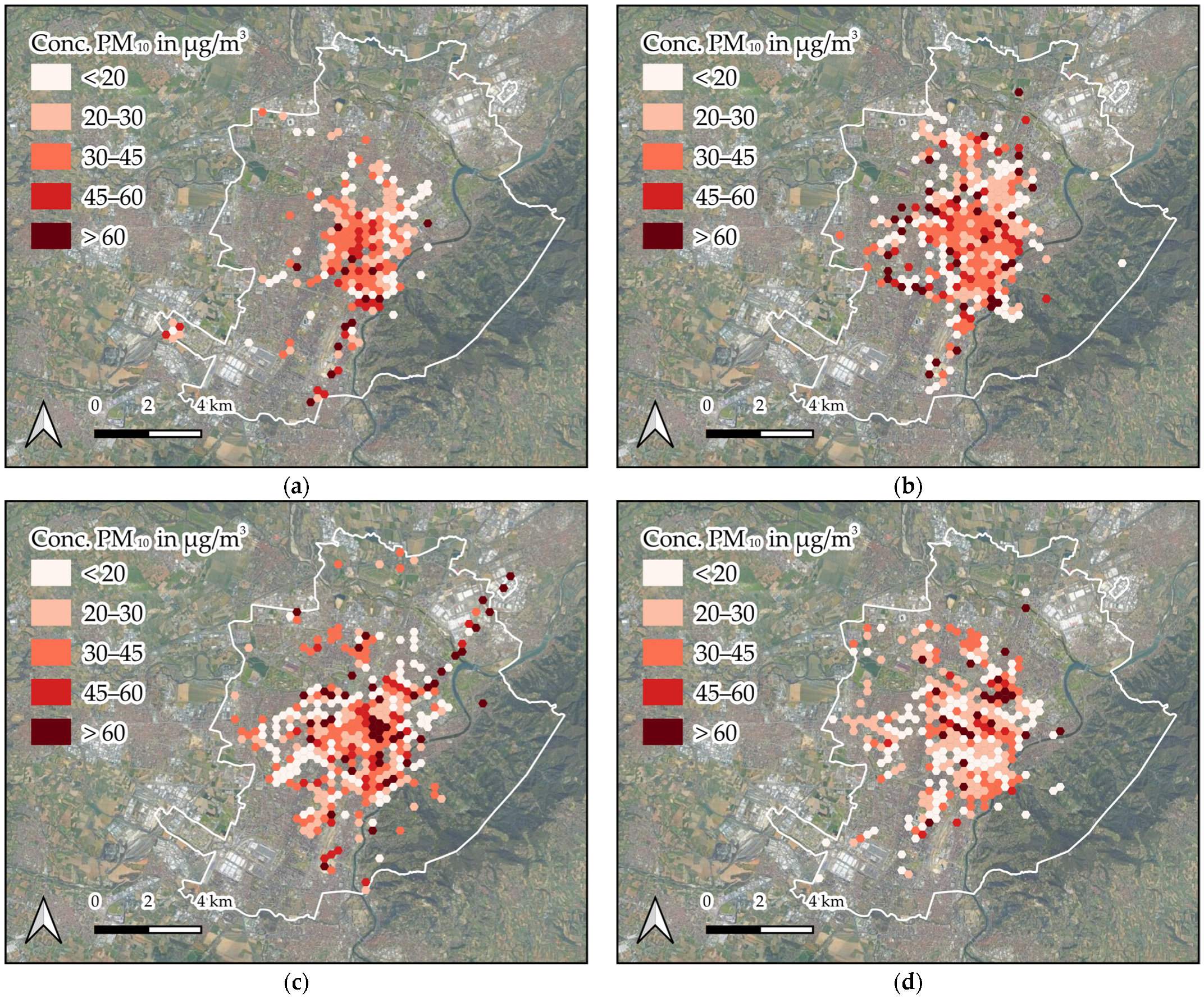

- Seasonal variations in measured air pollutants observed in the city of Turin (NW Italy) identified the north-western zone and the urban centre as the most polluted areas.

- The use of light and affordable instrumentation allows citizens to acquire the concentrations of five air pollutants in real time directly on their own smartphone.

- The use of wearable sensors that continuously monitor air quality will help to define targeted decisions to shape the development of smart cities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Low-Cost Sensors

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PMs | Particulate Matters |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| TVOCs | Total Volatile Organic Compounds |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| WGS | World Geodetic System |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| GHGs | Greenhouse Gases |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-03-2014-7-million-premature-deaths-annually-linked-to-air-pollution (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/air-pollution-documents/air-quality-and-health/aap_bod_results_may2018_final.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/harm-to-human-health-from-air-pollution-2024 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/air-pollution-levels-across-europe (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Jutze, G.A.; Tabor, E.C. The Continuous Air Monitoring Program. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1963, 13, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, H.; de Nazelle, A. The role of personal air pollution sensors and smartphone technology in changing travel behaviour. J. Transp. Health 2018, 11, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Gerboles, M.; Barbiere, M.; Kotsev, A.; Lagler, F.; Borowiak, A. Review of Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring; EUR 29826; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Kok, G.; Persijn, S.; Sauerwald, T. Review of Portable and Low-Cost Sensors for the Ambient Air Monitoring of Benzene and Other Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors 2017, 17, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Srinivasan, R. A Systematic Review of Air Quality Sensors, Guidelines, and Measurement Studies for Indoor Air Quality Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, A.; Mancini, T.; Paolozzi, M.C.; Macis, S.; Marcelli, A.; Petrarca, M.; Radica, F.; Tranfo, G.; Lupi, S.; Della Ventura, G. High Sensitivity real-time VOCs monitoring in air through FTIR Spectroscopy using a Multipass Gas Cell Setup. Sensors 2022, 22, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthammer, T. TVOC—Revisited. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mølhave, L.; Nielsen, G.D. Interpretation and Limitations of the Concept “Total Volatile Organic Compounds” (TVOC) as an Indicator of Human Responses to Exposures of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC). Indoor Air 1992, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaretti, G.; Cadum, E.; Migliore, E.; Cavallo, F. Traffic air pollution and hospital admission for asthma: A case-control approach in a Turin (Italy) population. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2005, 78, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, P.; Miotti, J.; Locatelli, F.; Antonicelli, L.; Baldacci, S.; Battaglia, S.; Bono, R.; Corsico, A.; Gariazzo, C.; Maio, S.; et al. Long-term residential exposure to air pollution and risk of chronic respiratory diseases in Italy: The BIGEPI study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, R.; Romanazzi, V.; Bellisario, V.; Tassinari, R.; Trucco, G.; Urbino, A.; Cassardo, C.; Siniscalco, C.; Marchetti, P.; Marcon, A. Air pollution, aeroallergenes and admissions to pediatric emergency room for respiratory reasons in Turin, northwestern Italy. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaretti, G.; Dalmasso, P.; Gregori, D. Air pollution effects on the respiratory health of the resident adult population in Turin, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2007, 17, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina, M.; Caramitti, G.; Panepinto, D.; Zanetti, M. Air quality and photochemical reactions: Analysis of NOx and NO2 concentrations in the urban area of Turin, Italy. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2022, 15, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecca, D.; Boanini, C.; Vaccaro, V.; Gallione, D.; Mastomattero, N.; Clerico, M. Spatial variation, temporal evolution, and source direction apportionment of PM1, PM2.5, and PM10: 3-year assessment in Turin (Po Valley). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallione, D.; Mastromatteo, N.; Clerico, M. Analysis of PM Concentrations in Turin: Annual Trend and Monthly and Daily Mean Concentration. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. Remediat. 2025, 13, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina, M.; Esfandabadi, Z.S.; Panepinto, D.; Zanetti, M. Traffic-induced atmospheric pollution during the COVID-19 lockdown: Dispersion modeling based on traffic flow monitoring in Turin, Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizza, V.; Torre, M.; Tratzi, P.; Fazzini, P.; Tomassetti, L.; Cozza, V.; Naso, F.; Marcozzi, D.; Petracchini, F. Effects of deployment of electric vehicles on air quality in the urban area of Turin (Italy). J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicco, A.; Diana, M. Air emissions impacts of modal diversion patterns induced by one-way car sharing: A case study from the city of Turin. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 91, 102685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, E.; Negro, E.; Carlucci, C.; Nasso, A.; Struppek, M. Actions against air pollution in Turin for a healthy and playable city. Cities Health 2019, 3, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotto, A.; Bargero, C.; Racca, E.; Brizio, E. Key Elements to Project and Realize a Network of Anti-Smog Cannons (ASC) to Protect Sensitive Receptors from Severe Air Pollution Episodes in Urban Environment. Air 2025, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnosija, N.; Zamora, M.L.; Rule, A.M.; Payne-Sturges, D. Laboratory Chamber Evaluation of Flow Air Quality Sensor PM2.5 and PM10 Measurements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattan, I.A.; Al Iftaihat, Y.; El Farag, M.S. The integrity of air pollution data measurements and their legal implications, a case study in Qatar on air pollution of the French company plume labs. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 8892–8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plume Labs. Available online: https://plumelabs.zendesk.com/hc/en-us (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Plume Labs. How Accurate Is Flow? Available online: https://plumelabs.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/360025092554-How-Accurate-is-Flow (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Unicsv 2.0. Available online: https://unicsv20.altervista.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System, version 3.40.2; Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project; QGIS Development Team: Zurich, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- IEA. Renewables 2020; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2020/renewable-heat (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- IEA. Renewables 2022; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Keiner, D.; Barbosa, L.; Bogdanov, D.; Aghahosseini, A.; Gulagi, A.; Oyewo, S.; Child, M.; Khalili, S.; Breyer, C. Global-Local Heat Demand Development for the Energy Transition Time Frame Up to 2050. Energies 2021, 14, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banja, M.; Carlsson, J.; Roca Reina, J.C.; Toleikyte, A.; Monforti-Ferraio, F.; Crippa, M.; Pisoni, E. Air pollution Trends in the Heating and Cooling Sector in the EU-27: A Forward Look to 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Industrial Pollutant Releases to Air in Europe; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/industrial-pollutant-releases-to-air (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ge, J. Influences of urban shape on city-scale heat and pollutants dispersion under calm and moderate background wind condition. Build. Environ. 2025, 270, 112530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, G.M.; Parri, L.; Vitanza, E.; Pozzebon, A.; Fort, A.; Mocenni, C. WeAIR: Wearable Swarm Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring to Foster Citizens’ Awareness of Climate Change. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2025, 94, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, N.H.; Zaidan, M.A.; Fung, P.L.; Lagerspetz, E.; Aula, K.; Varjonen, S.; Siekkinen, M.; Robeiro-Hargrave, A.; Petaja, T.; Matsumi, Y.; et al. Transit pollution exposure monitoring using low-cost wearable sensors. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 98, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, M.; Cappon, G.; Vettoretti, M. Assessing Personal Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter with Wearable Sensors and Ventilation Rate Models. In Proceedings of the 8th National Congress of Bioengineering, GNB 2023, Padova, Italy, 21–23 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wako, W.G.; Clemens, T.; Ogletree, S.; Williams, A.J.; Jepson, R. Validity, reliability and acceptability of wearable sensor devices to monitor personal exposure to air pollution and pollen: A systematic review of mobility based exposure studies. Build. Environ. 2025, 277, 112931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureau, R.J.; Pigliautile, I.; Pisello, A.L. A New Wearable System for Sensing Outdoor Environmental Conditions for Monitoring Hyper-Microclimate. Sensors 2022, 22, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines. Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; WHO European Centre for Environment and Health: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, D.J.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Heroux, M.E.; Rapp, R.; Kelly, F.J. Nitrogen dioxide. In WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; pp. 201–248. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, P.; Tuovinen, J.P.; Niemi, J.V. Primary NO2 emissions and their role in the development of NO2 concentrations in a traffic environment. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Piemonte. Aria—Qualità Dell’aria Piemonte [Internet]; Regione Piemonte: Piemonte, Italy; Available online: https://aria.ambiente.piemonte.it/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Città di Torino. Qualità Dell’aria a Torino [Internet]; Città di Torino: Torino, Italy; Available online: https://www.comune.torino.it/ambiente/aria/aria_torino/index.shtml (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bergam, M.; Huang, X.; Baudino, S.; Caissard, J.C.; Dudareva, N. Plant volatile organic compounds: Emission and perception in a changing world. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 85, 102706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Cheng, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y. Characteristics and Source Analysis of PM1 in a Typical Steel-Industry City, Southwest China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Roy, A.; Masiwal, R.; Mandal, M.; Popek, R.; Chakraborty, M.; Prasad, D.; Chylinski, F.; Awasthi, A.; Sarkar, A. Comprehensive Analysis of PM1 Composition in the Eastern Indo-Gangetic Basin: A Three-Year Urban Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.K.; Kumar, A.; Pratap, V.; Singh, A.K. Seasonal characteristics of PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 over Varanasi during 2019–2020. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 909351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, B.; Ditta, A.; Alam, K.; Sorooshian, A.; Din, B.U.; Iqbal, R.; Rahman, M.H.; Raza, A.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Elshikh, M.S. Wintertime investigation of PM10 concentrations, sources, and relationship with different meteorological parameters. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARPA Piemonte. Il Clima in Piemonte 2022; ARPA Piemonte Department of Natural and Environmental Risks: Turin, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.arpa.piemonte.it/sites/default/files/media/2023-11/anno_2022_solare.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- iLMeteo. Historical Weather Archive [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ilmeteo.it/portale/archivio-meteo (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- University of Turin. Meteorological Observatory of the University of Turin, Department of Physics [Internet]. Available online: https://www.meteo.dfg.unito.it/anno-2022# (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Umweltbundesamt. Annual Tabulation—Air Data: PM10 Limit Values; German Federal Environment Agency: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/en/data/air/air-data/annual-tabulation (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32008L0050 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Ivanković, A.; Dronjić, A.; Martinović Bevanda, A.; Talić, S. Review of 12 Principles of Green Chemistry in Practice. Int. J. Sustain. Green Energy 2017, 6, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pollutant | Statistical Indexes | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | Median | 18.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 19.0 |

| MAD | 8.0 (44.4%) (a) | 7.0 (41.0%) | 8.0 (44.4%) | 9.0 (47.4%) | |

| TVOCs | Median | 163.0 | 167.0 | 158.0 | 159.0 |

| MAD | 37.0 (22.7%) | 26.0 (15.6%) | 41.0 (25.9%) | 25.0 (15.7%) | |

| PM10 | Median | 28.7 | 27.8 | 34.7 | 36.0 |

| MAD | 17.1 (59.6%) | 17.6 (61.3%) | 19.2 (55.3%) | 18.9 (52.5%) | |

| PM2.5 | Median | 19.6 | 11.5 | 22.2 | 30.3 |

| MAD | 16.2 (82.6%) | 8.7 (75.6%) | 17.9 (80.6%) | 18.4 (60.7%) | |

| PM1 | Median | 22.0 | 20.0 | 21.0 | 23.0 |

| MAD | 13.0 (59.1%) | 14.0 (70.0%) | 13.0 (61.9%) | 13.0 (56.5%) |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | 3.2 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 13.0 | 19.7 | 24.4 | 27.1 | 25.1 | 19.5 | 17.0 | 9.1 | 3.8 |

| Humidity [%] | 69.3 | 60.2 | 54.1 | 58.0 | 67.5 | 61.0 | 54.8 | 59.2 | 63.7 | 79.9 | 76.0 | 86.7 |

| Wind speed [km/h] | 5.9 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.1 |

| Precipitation (b) [mm] | 1.2 | 1.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 50.6 | 15.0 | 36.0 | 62.4 | 31.0 | 45.0 | 33.5 | 48.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chicco, J.M.; Prenesti, E.; Morando, V.; Fiermonte, F.; Mandrone, G. Wearable Sensors to Estimate Outdoor Air Quality of the City of Turin (NW Italy) in an IoT Context: A GIS-Mapped Representation of Diffused Data Recorded over One Year of Monitoring. Smart Cities 2026, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010007

Chicco JM, Prenesti E, Morando V, Fiermonte F, Mandrone G. Wearable Sensors to Estimate Outdoor Air Quality of the City of Turin (NW Italy) in an IoT Context: A GIS-Mapped Representation of Diffused Data Recorded over One Year of Monitoring. Smart Cities. 2026; 9(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChicco, Jessica Maria, Enrico Prenesti, Valerio Morando, Francesco Fiermonte, and Giuseppe Mandrone. 2026. "Wearable Sensors to Estimate Outdoor Air Quality of the City of Turin (NW Italy) in an IoT Context: A GIS-Mapped Representation of Diffused Data Recorded over One Year of Monitoring" Smart Cities 9, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010007

APA StyleChicco, J. M., Prenesti, E., Morando, V., Fiermonte, F., & Mandrone, G. (2026). Wearable Sensors to Estimate Outdoor Air Quality of the City of Turin (NW Italy) in an IoT Context: A GIS-Mapped Representation of Diffused Data Recorded over One Year of Monitoring. Smart Cities, 9(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010007