1. Introduction

The emergence of shared micromobility has altered urban transport systems across cities worldwide. Since their commercial rollout in the late 2010s, e-scooters have been marketed as a flexible, low-emission solution for short urban trips. Providers often highlight their potential to reduce car dependency, enhance first- and last-mile connectivity, and contribute to more sustainable travel behaviours. These claims, frequently used to justify the presence and expansion of e-scooter services, have drawn increasing interest from researchers and policymakers seeking to evaluate their actual impacts on urban mobility systems [

1,

2,

3].

This study aims analyse the spatiotemporal dynamics of shared electric scooter use across Tel Aviv during the full calendar year of 2024. It explores three central questions: (1) How do time-of-day, weekday/weekend patterns, holidays, and weather influence demand for shared e-scooters? (2) How is the spatial distribution of scooter trips shaped by public transport accessibility, and do usage patterns reproduce or disrupt existing inequalities in urban connectivity? (3) To what extent do shared e-scooters function as a first- and last-mile mode within Tel Aviv’s broader multimodal transport system?

To answer these questions, the paper draws on a complete year of operational trip data from all licensed e-scooter providers in Tel Aviv, comprising millions of trips. This is integrated with high-resolution spatial indicators that capture public transport accessibility at the origin and destination level, enabling a detailed analysis of whether shared micromobility extends or concentrates access. Temporal patterns are investigated using STL (seasonal-trend decomposition using Loess), combined with weather overlays and generalized linear regression modelling to quantify the effects of calendar rhythms and meteorological variation.

This research makes three primary contributions. First, it leverages a full-year dataset from a city-wide fleet, enabling robust identification of seasonal, weekly, and weather-induced fluctuations in demand. Second, it offers a fine-grained integration of spatial and temporal analytics, combining behavioural trip data with GIS-based accessibility scores at scale. Third, it contributes one of the first systematic examinations of shared micromobility in a Middle Eastern city. Together, these elements provide insights into how shared e-scooters are embedded in the multimodal flows of a complex urban system.

The remaining structure of the paper is as follows: The next section outlines the literature background. The following one presents the data sources, processing steps, and methodological framework, including regression modelling, time-series decomposition, and accessibility assignment.

Section 4 presents the main empirical findings, beginning with a multivariate regression analysis of temporal and weather effects on scooter demand. This is followed by a decomposition of temporal patterns using STL and a detailed spatial analysis linking trip locations to public transport accessibility indicators. Thereafter, these findings are integrated into a discussion of policy implications. The final section concludes the study by summarizing key contributions and identifying avenues for future research in shared micromobility.

2. Background

A growing body of literature has examined usage patterns of shared e-scooters, with a focus on trip characteristics (distance, duration, purpose), socio-demographic user profiles, and spatial deployment. Studies in European and North American contexts show that e-scooters are often used for short trips averaging 1 to 3 km [

4] and tend to be concentrated in central areas with high population and employment density [

5,

6]. Research consistently finds that the most frequent users of shared e-scooters are younger, educated males, with a notable proportion being visitors rather than residents [

3,

7]. E-scooter use tends to peak in the afternoon and on weekends and is often associated with leisure, tourism, or short business-related trips rather than routine commuting [

3,

8,

9].

Environmental and weather conditions are key moderators of shared micromobility use. Precipitation in particular reduces e-scooter usage more significantly than it does for bicycles or e-mopeds [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Seasonality and daily climatic conditions were found to affect trip frequency and duration, making weather-sensitive operational planning critical [

10,

12]. Additionally, the expansion of fleets does not automatically lead to increased demand; diminishing returns and potential market saturation have been observed [

10,

14]. These findings suggest that scaling shared micromobility requires more than vehicle availability and should be contextually informed by land use patterns, behavioural preferences, and competing modes.

Despite their potential for first- and last-mile connectivity, shared e-scooters are often deployed in areas already well-served by public transport, which limits their contribution to bridging accessibility gaps [

3,

8,

15,

16]. Research indicates that their use is skewed toward high-accessibility, high-demand zones, which may inadvertently increase inequalities in urban mobility [

15]. While they can complement transit networks, their integration is frequently uncoordinated. For instance, users often employ e-scooters to connect to public transport stations, but few systems incorporate this into planning or infrastructure provision [

17,

18].

Technological and operational advancements have been pivotal in managing e-scooter systems. Vanus and Bilik [

19] emphasize the use of Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) and Mobility Energy Productivity (MEP) metrics to anticipate demand hotspots and improve operational efficiency. These tools, when combined with Internet-of-Things (IoT) platforms and app-based usage data, support dynamic vehicle rebalancing and charging. Studies suggest that such integration is vital for enabling e-scooter fleets to function within smart urban environments [

19,

20,

21]. More recently, deep reinforcement learning methods have been explored to optimize vehicle redistribution and reduce system inefficiencies [

22]. While promising, these technologies require substantial infrastructure investment and raise questions about data privacy and governance.

From a sustainability perspective, shared e-scooters offer potential benefits, but their real-world impact remains questioned. Although they can reduce emissions when replacing private car trips, their environmental benefit is often diluted by short vehicle lifespans, frequent maintenance needs, and the energy costs of fleet rebalancing and charging [

8,

20,

22]. The actual modal shift patterns are essential here; when e-scooters replace walking, cycling, or transit trips, as several studies suggest they often do, the net sustainability effect may be negative [

2,

8].

Safety is another widely acknowledged concern. Shared e-scooters have been linked to high injury rates, particularly among riders without helmets or training [

3,

23,

24]. Infrastructure deficiencies and conflicts with pedestrians are major contributing factors. In parallel, the visual and promotional framing of e-scooters, especially on social media, frequently omits safety guidelines, which can reinforce risky behaviour [

23]. These issues complicate efforts to frame shared e-scooters as a public health positive, despite their potential role in improving accessibility and urban mobility.

Governance challenges persist in the regulation and enforcement of shared micromobility systems. The speed of e-scooter adoption has often outpaced municipal planning processes, resulting in fragmented regulatory responses [

3,

15,

25]. Common issues include unclear rules around parking, use of pedestrian infrastructure, and service area boundaries. Furthermore, cities frequently lack the institutional capacity or legal instruments to manage data-sharing agreements with private operators, which hinders transparency and effective planning [

3]. As Gössling [

25] notes, integrating e-scooters into urban mobility regimes requires a more systemic and anticipatory policy framework than currently exists in many cities.

In comparing e-scooters with other forms of shared micromobility, particularly e-bikes, notable differences in user profiles, infrastructure requirements, and substitution effects have emerged. Studies suggest that e-bikes are more frequently used for commuting and longer-distance trips compared to e-scooters, which are often preferred for short, recreational rides [

2,

8]. E-bikes tend to attract a more diverse user base, including older users and individuals with lower physical fitness, due to the assisted pedalling support. In contrast, e-scooters are less physically demanding but more sensitive to road surface quality and micro-barriers, which can discourage usage in areas with poor infrastructure [

3,

5]. These differences underscore the importance of evaluating micromobility modes not as interchangeable, but as complementary services shaped by contextual, behavioural, and urban design factors. Additionally, the governance and business models between e-scooters and e-bikes differ significantly. Many cities have actively integrated bike-share systems into public transport planning, often subsidizing operations or providing physical docking stations. In contrast, e-scooters are more often deployed under private, dockless models that prioritize rapid scalability over long-term planning. This has implications for urban clutter, equity of access, and system longevity [

3,

15].

Methodologically, studies on shared micromobility have employed a range of approaches, including descriptive statistics, time-series analysis, spatial clustering, and regression-based modelling. Recent contributions have expanded into machine learning techniques such as clustering, random forests, and neural networks to predict demand patterns and assess factors influencing usage [

10,

12,

22]. These methods have enabled researchers to explore interactions between variables such as weather, built environment, and time of day, offering more nuanced insights into behavioural patterns. Nonetheless, the lack of longitudinal studies and limited availability of high-resolution operational data in many cities still constrain the generalisability of findings across different contexts [

3,

8].

A growing concern within the literature is the socio-spatial equity of shared micromobility deployment. While e-scooter systems are often justified as a tool for improving urban accessibility, evidence suggests that they primarily serve central, high-income areas, leaving out lower-income and peripheral neighbourhoods [

3,

15]. Barriers to adoption include not only geographic coverage, but also pricing structures, smartphone access, and digital literacy. Some cities have experimented with subsidies or geographic service requirements to counteract these patterns, but long-term evidence on the efficacy of such interventions remains limited. Addressing equity challenges requires both regulatory oversight and inclusive design principles that go beyond the current commercial deployment logic.

User perception is also emerging as a relevant lens for understanding adoption and behavioural patterns in shared micromobility. Studies have shown that perceptions of safety, convenience, and social acceptability influence mode choice, even when objective infrastructure or availability is similar. Riders may avoid certain areas due to perceived danger or lack of social legitimacy associated with e-scooter use, while non-users may express concern over sidewalk obstructions or perceived regulatory gaps [

6,

23].

Equally important is the issue of data sharing between operators and public authorities. While high-resolution trip and system data are crucial for effective urban planning and regulatory oversight, many cities face challenges in accessing standardized and timely datasets from private providers. This fragmentation undermines efforts to monitor performance, enforce equity goals, or conduct impact assessments [

3]. Some jurisdictions have begun mandating open data frameworks or standardized reporting protocols, but compliance and interoperability remain limited.

While shared micromobility has received growing academic attention in recent years, empirical research remains geographically skewed. Most studies have focused on Western European and North American contexts [

3,

8], leaving significant gaps in understanding usage patterns in cities of the Global South and the Middle East. As a result, municipalities such as Tel Aviv, where shared e-scooters have seen rapid uptake, often implement policies and infrastructure without the benefit of context-specific evidence. Moreover, relatively few studies examine how micromobility usage interacts with urban accessibility inequalities, despite the growing relevance of equity concerns in transport planning.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs an integrated framework to analyse the temporal, spatial dynamics of shared e-scooter usage in Tel Aviv. The analysis is based on a dataset comprising a full calendar year of operational records from all licensed e-scooter providers active in the city during 2024. Methodologically, the study combines three analytical components: time-series decomposition to identify temporal regularities, multivariate regression modelling to quantify the influence of institutional and environmental covariates, and spatial analysis to examine patterns of accessibility and their relationship to usage. These methods were chosen to distinguish habitual usage patterns from context-specific disruptions, and to assess whether shared e-scooters serve as an effective complement to existing modes of urban transport.

3.1. Study Location and Data Sources

The primary dataset was derived in a format of Mobility Data Specification (MDS) [

26], and comprises 30,177,871 event-level observations corresponding to changes in vehicle state (these are:

trip start, trip end,

provider pickup,

provider drop off,

maintenance). Each record includes a timestamp, a unique device identifier (

device id), GPS coordinates, and categorical descriptors of the vehicle. Starting from the raw event ledger, we normalized timestamps to local time, sorted records by (

device id, timestamp), and removed exact duplicates and entries with invalid coordinates (e.g., outside the municipal geofence), retaining 30,081,599 cleaned records. Trip reconstruction was performed strictly within each device stream: for a given

device id, we paired each

trip start with the earliest subsequent unmatched

trip end for the same device, yielding 9,664,064 candidate start–end pairs; intervals in which a provider-initiated relocation or maintenance event occurred between the markers were classified as non-user movements and excluded (946 intervals). To ensure one-to-one matching, unmatched starts/ends were discarded (5327 starts), and occasional overlaps were resolved by retaining the most recent unmatched start preceding a given end in that device’s sequence. For each remaining pair, we computed elapsed time and great-circle distance (haversine) and then applied validity thresholds (duration 1–120 min; start–end distance < 45 km), which removed 497,223 duration outliers and 418 long-distance pairs. The final analysis dataset contains 9,166,423 valid trips (mean duration 10.91 min; median 8.40; mean distance 1.52 km; median 1.29 km).

Weather data were obtained from a coastal meteorological station in Tel Aviv, providing 10 min interval measurements of temperature and precipitation. These were aggregated to hourly resolution and joined to the trip data by temporal key. Observations with missing weather values were excluded from regression and time-series analysis. Tel Aviv has a Mediterranean climate with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers; average daily temperatures are ~13–14 °C in January and ~26–27 °C in August. Rain is highly seasonal: using a ≥1 mm “wet day” threshold, there are ~7 wet days in January and virtually none in June–September (≈33 days/year in total) [

27].

Spatial information was processed by assigning each trip origin and destination to a 200 × 200 m grid cell, harmonized with a national public transport accessibility classification. Each grid cell is assigned a connectivity level based on proximity to fixed-rail infrastructure and frequency of bus service during peak hours. These levels were subsequently normalized on a continuous scale and used to calculate zonal averages for accessibility at origin and destination.

Preprocessing steps were implemented using Python 3.12.4, with data manipulation conducted in pandas and geospatial operations performed using GeoPandas and Shapely. Quality control included checks for duplicated events, spatial outliers (outside Tel-Aviv service area), and incomplete trip pairings.

3.2. Regression Modelling

A multivariate modelling framework was specified to estimate the association between hourly scooter usage and a set of temporal and environmental covariates. The dependent variable (yt) is the number of trips initiated in each hour. Independent variables include time-of-day, institutional calendar effects (weekday, weekend, holiday, summer), and weather conditions (temperature and precipitation). Time-of-day was operationalized as a six-level categorical variable: night (01:00–03:59), early morning (04:00–06:29), morning peak (06:30–09:59), midday (10:00–14:59), afternoon peak (15:00–19:59), and evening (20:00–00:59), with midday serving as the reference category. Day-type indicators were constructed to capture the institutional week in Tel Aviv, including a separate binary variable for Thursdays to reflect its transitional status between weekday and weekend.

Weather variables include hourly average temperature (°C) and a binary flag indicating the presence of any recorded precipitation. We included interactions between time-of-day and weather (temperature × time-of-day; rain × time-of-day) so that weather effects may vary across the day. Most regressors are binary indicator (dummy) variables; the only continuous predictor is temperature, which enters unstandardized in °C and is mean-centred in interaction models to aid interpretation. Multicollinearity diagnostics were conducted using variance inflation factors. We subsequently re-estimated a reduced specification that excludes interaction terms not statistically significant at the 5% level under HAC(24) standard errors [

28,

29].

We estimated a linear OLS regression with robust inference as our main specification. The model is given by

where

values are time-of-day dummies for

in {

night,

early morning,

morning peak,

afternoon peak,

evening} with midday omitted;

is the hourly temperature;

is a precipitation indicator;

is in {

weekend,

Thursday,

holiday,

summer}; and

is the error term.

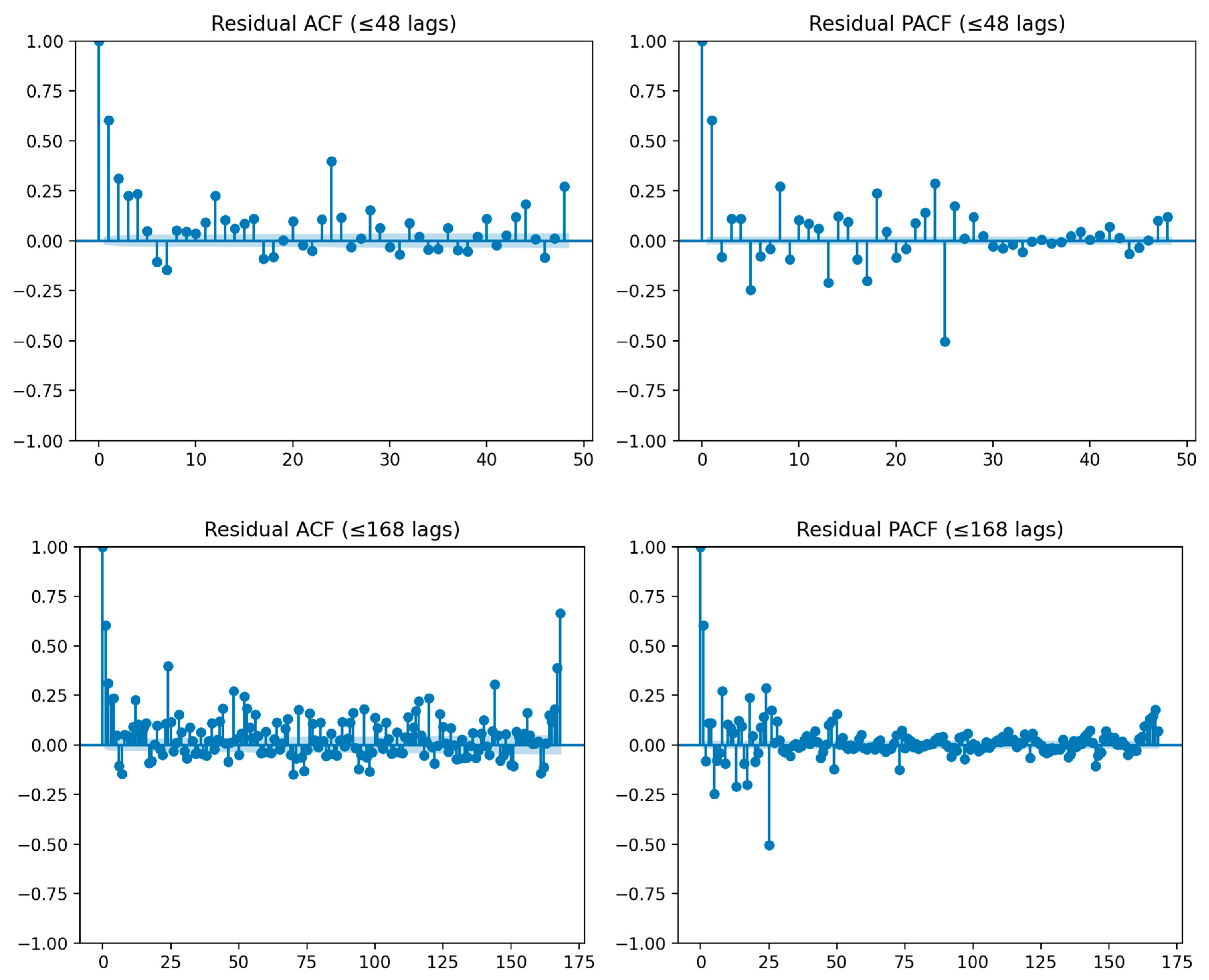

The model was estimated using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust inference. Residual diagnostics (ACF/PACF correlograms are presented on

Figure 1) and Ljung–Box Q tests at 24/48/168 lags (Q

(24) ≈ 7870; Q

(48) ≈ 9715; Q

(168) ≈ 24,278; all

p < 0.001) show short-run persistence and clear spikes at multiples of 24 h in the ACF, i.e., the expected diurnal/weekly structure for hourly demand. Because residuals also exhibit heteroskedasticity, we report HC3 standard errors in the main table and verify inference with Newey–West/HAC(24) and cluster-by-date standard errors [

28,

29,

30].

For comparison, we re-estimated the specification using Poisson, quasi-Poisson, and Negative Binomial (NB2). Poisson exhibited severe over-dispersion (Pearson χ2/df ≈ 124). NB2 accommodated over-dispersion (α ≈ 0.19) and produced coefficients consistent with OLS but slightly worse predictive accuracy (NB2 RMSE ≈ 360 vs. OLS RMSE ≈ 349 trips/h), with OLS generating a negligible share of negative fitted values (~0.11%). Given the marginally better fit, transparent interpretation in trips/h, and robust inference under serial dependence, OLS was kept as the main model.

3.3. Time-Series Decomposition

To identify recurrent temporal patterns in demand and distinguish them from trend and residual variation, STL [

31] was applied to trip counts aggregated at both hourly and daily resolutions. STL is a robust nonparametric technique that decomposes a time series into trend, seasonal, and residual components. Its ability to accommodate non-stationary seasonality and irregular spacing of data makes it particularly well-suited to the analysis of shared micromobility usage.

Decomposition at the hourly level was used to isolate daily and weekly cycles. Weekly and monthly decompositions were omitted due to the limited interpretability of these components within a single-year observation window. In the hourly STL, we set the seasonal period to 24. We use an odd-span seasonal window of 25 and a low-pass window of 25 to yield a smooth yet responsive daily cycle, and a 169 h (≈1-week) window for the long-run trend. Local fits are linear to avoid over-fitting short-run wiggles, and we do not thin the data, so every observation contributes, preserving the timing of sharp changes. We also used robust re-weighting to down-weight outliers. The residual component of the decomposition was subsequently analysed in relation to weather variables, allowing for the detection of anomalies attributable to external factors such as rainfall.

We checked the sensitivity of the hourly STL around the main specification. Small changes to the smoothing windows (seasonal 23–27; low-pass 25–31) mainly affect curve smoothness and barely move the variance shares: seasonal ≤0.2 percentage points (pp), trend 0.0 pp, residual ≤0.1 pp. Turning off robust re-weighting has a larger, expected effect: short, sharp shocks (e.g., heavy rain hours or holiday closures) pull on the local fits, reducing the seasonal share by ~16.6 pp, increasing the trend by ~1.2 pp, and reducing the residual by ~5.5 pp. Even so, the qualitative picture is unchanged: a dominant diurnal cycle and pronounced weather-related dips remain. We therefore keep robust STL for the main results, as it limits outliers’ influence while leaving short-term anomalies in the remainder.

The decision to adopt STL, as opposed to alternative filtering or decomposition techniques (e.g., classical seasonal adjustment or Fourier-based methods), was motivated by its robustness to outliers, its flexibility in capturing nonlinear cyclicities, and its transparency in isolating distinct components of temporal structure [

31].

3.4. Spatial Distribution and Accessibility Patterns

Accessibility to public transportation was measured using a national spatial index based on a uniform 200 × 200 m grid. Each cell in this grid was assigned an accessibility category derived from the availability and frequency of nearby public transport services, including buses, heavy rail, light rail, and bus rapid transit (BRT). The classification system consisted of five ordinal levels. The highest level included cells that contained, or were adjacent to, train, light rail, or BRT stations, or bus stops with average headways of at most 10 min during both morning and evening peak hours. Lower levels were defined by decreasing frequency thresholds: 10–20 min, 20–30 min, and 60 min and more. Cells without any qualifying services, or without adjacent cells that met the qualifying criteria, were assigned the lowest category, corresponding to no effective access. The 200 × 200 m grid size was selected to provide a uniform national framework that balances spatial detail and computational efficiency. Accessibility for each cell was determined based on the presence of qualifying services within approximately a 300 m walking distance (approximately a 5 min walk).

For each Traffic Analysis Zone, a normalized accessibility score ranging from 0 to 1 was computed. This score represents a weighted average of the ordinal connectivity levels of all grid cells falling within the zone, restricted to those grids located in built-up areas or adjacent to paved roads. Grid cells located in open, agricultural, or uninhabited areas were excluded from the calculation. The weighting reflects the proportion of each connectivity category present within the zone and accounts for spatial variation in access quality.

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological transition from the five-tier public transport service classification to the aggregated accessibility measure at the Traffic Analysis Zone level. The accessibility score assigned to each TAZ was computed as a weighted average of the service levels of the 200 × 200 m grid cells it contains. Specifically, the score integrates the proportion of grid cells with varying levels of service frequency during both morning and evening peak hours, according to the following formula:

where

denotes the number of grid cells falling inside the TAZ or along its boundaries, served by mass transit (train, LRT, or BRT) or with average headways of ≤10 min during both peaks;

corresponds to grids with ≤10 min in the morning and ≤20 min in the evening;

includes grids with ≤20 min in the morning and ≤30 min in the evening;

denotes grids with ≤60 min; and

is a less frequent service. The sum value was normalized by the total number of grid cells in each TAZ, ensuring comparability across areas. A perfect score (1) is obtained when all grid cells within a zone fall into the highest service level, indicating full accessibility to high-frequency or mass-transit services. The resulting zone-level accessibility pattern is shown in the bottom-right panel of

Figure 2.

Each scooter trip was then assigned two accessibility scores: origin accessibility and destination accessibility, corresponding to the polygon in which the trip’s origin and destination coordinates were located. This spatial linkage enabled analysis of trip behaviour in relation to multimodal transport access conditions, using a high-resolution and behaviourally meaningful index.

Analytical procedures included the construction of histograms and decile plots of origin accessibility, destination accessibility, and Δaccessibility (difference between destination and origin scores), as well as origin–destination matrix. This matrix was normalized and visualized to identify directional flow structures across the accessibility spectrum and to assess whether shared micromobility serves to bridge accessibility gaps or is concentrated in already well-connected areas.

4. Results

The dataset analysed in this study comprises a full calendar year (2024) of shared electric scooter trip data across Tel Aviv, totalling more than 9,000,000 trips. These were reconstructed from event-level mobility logs compliant with the MDS and represent all licensed operators in the city. The mean trip duration was 10.91 min with a median = 8.40 min. The average trip length was 1.53 km, and the average speed per trip was 10.08 km/h. Average daily utilization was 3.54 trips per scooter, covering approximately 6.88 km per day.

The aggregated statistics reflect a high operational intensity and reinforce the notion that scooters serve as a short-range, flexible solution for intra-urban mobility. The annual trend with weather visible is presented in

Figure 3.

4.1. Temporal and Institutional Determinants of Scooter Demand

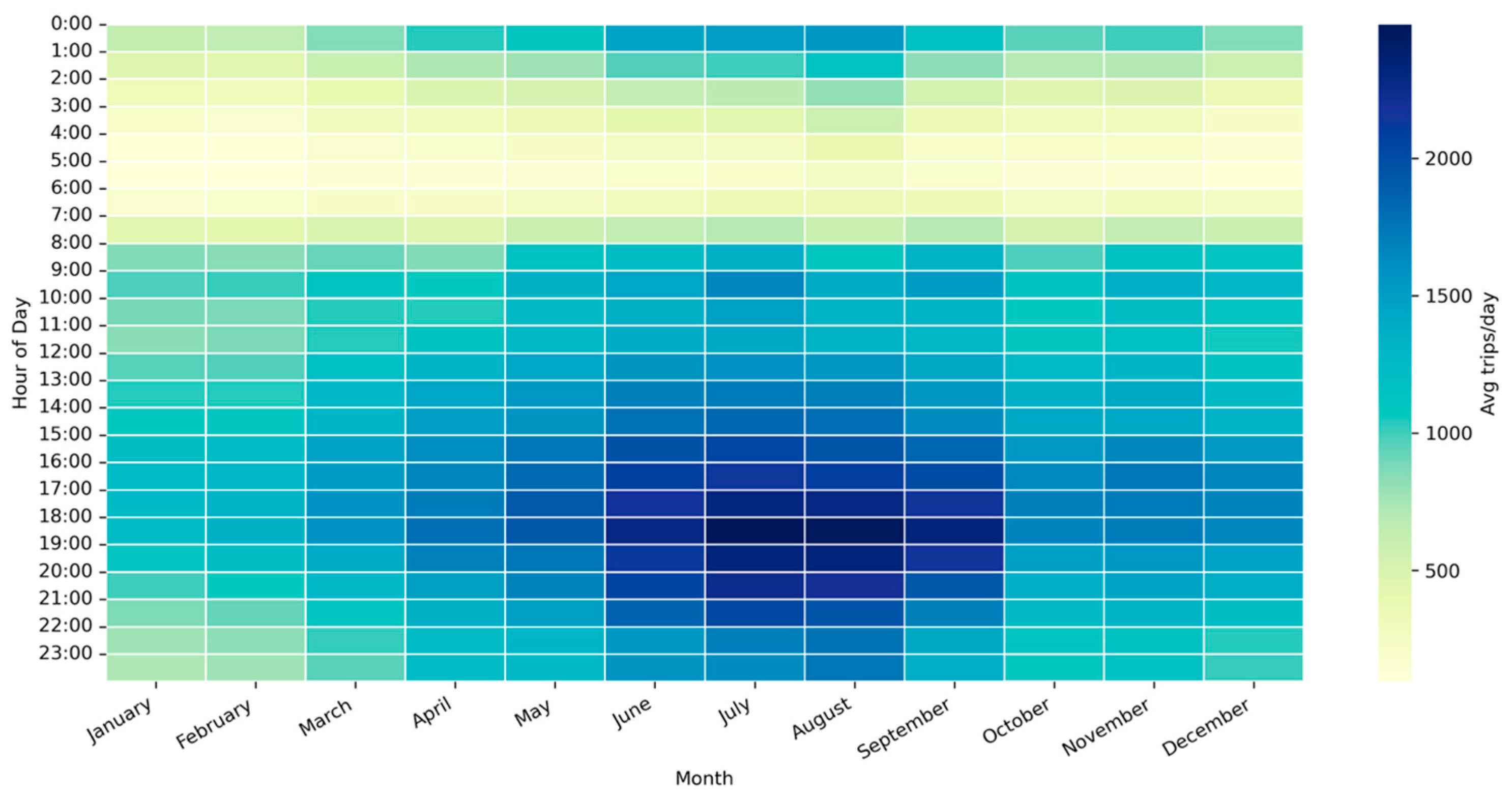

To understand the structural drivers of hourly scooter demand, we estimated an OLS regression model using the full trip dataset. The model achieved an adjusted R2 of 0.719 (HAC-24 verified), indicating high explanatory power. The regression results reveal a clear temporal structure in scooter demand. We used midday (10:00–14:59) as the reference category. Demand is highest in the afternoon peak (coef. ≈ +498), higher in the evening (β ≈ +185), lower in the morning peak (coef. ≈ −297), and much lower at night (coef. ≈ −509) and in the early morning (coef. ≈ −1028).

Figure 4 further illustrates these trends, revealing how usage varies across the week. Weekday patterns show a pronounced bimodal structure, with activity rising during morning and afternoon commuting periods. In contrast, weekend usage flattens and shifts later in the day, consistent with leisure-oriented behaviour.

Institutional calendar effects are especially prominent. Thursdays are busier (coef. ≈ +133), capturing Tel-Aviv’s late-week rhythm. Weekends are slightly quieter overall (coef. ≈ −59). Holidays reduce usage (coef. ≈ −164), and summer months show an increase (coef. ≈ + 59). These structural effects illustrate the integration of shared mobility into predictable social patterns.

Weather–time interactions clarify when conditions matter most. Temperature has a positive baseline effect at midday of about +33 trips/h per °C. This effect is stronger in the afternoon and evening (additional +26.7 and +24.6 trips/h per °C, respectively), and much weaker before dawn (early morning −27.6; morning peak −12.6). Thus, a 1 °C rise implies roughly +60 trips/h in the afternoon peak and ~+6 trips/h in the early morning. Rain strongly suppresses demand at midday (coeff. ≈ −239), but its impact is less negative at night and early morning (night × rain + 80.6; early morning × rain + 180.1), implying net reductions of ~−159 and ~−59 trips/h in those periods, respectively.

While holidays suppress usage (coef. ≈ −164), they do not eliminate it. This residual activity could reflect tourism, leisure, or intra-neighbourhood travel that persists even when major destinations are closed. Similarly, although rainfall is a strong deterrent, its effects are not absolute, suggesting a base level of resilient demand, perhaps among users with limited modal alternatives or trips within close distances.

Together, these findings underscore the structured nature of e-scooter usage: it follows well-defined temporal cycles, responds predictably to environmental triggers, and is embedded in institutional rhythms. This makes demand both forecastable and manageable with appropriately timed interventions and service design.

Table 1 presents the full set of coefficients with HC3 standard errors (main), alongside HAC-24 and cluster-by-date checks.

4.2. Time-Series Decomposition

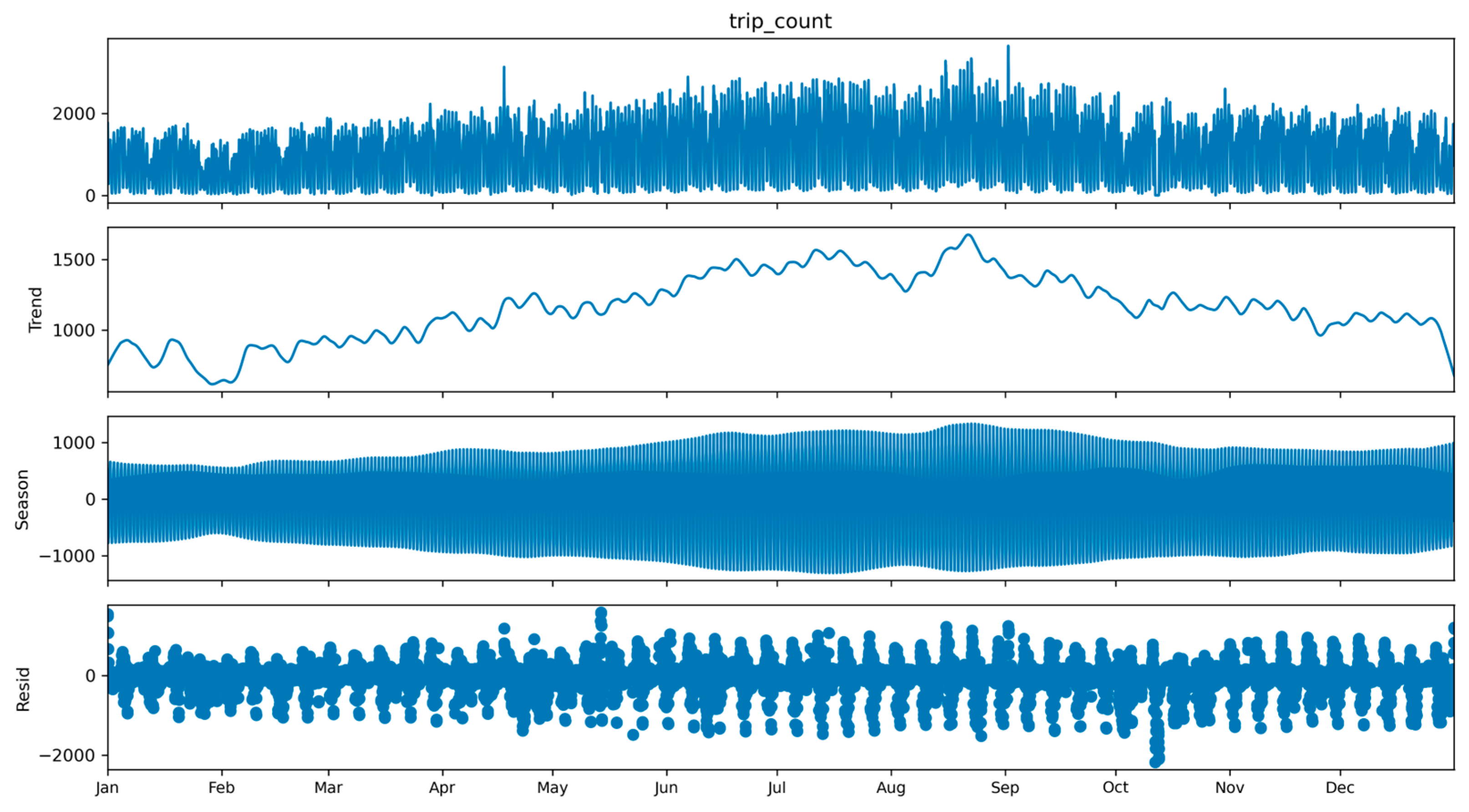

Building on the regression results presented in the previous section, we turn to time-series decomposition to understand how temporal demand evolves beyond modelled averages. The STL decomposition of daily scooter usage presented in

Figure 5 allowed us to isolate longer-term seasonal patterns and short-term anomalies, including those that cannot be fully explained by regression coefficients. At the hourly level, 83.8% of the variance in scooter usage was attributed to repeating daily cycles, underlining the role of diurnal structure linked to commuting and routine travel. An additional 12.4% of the variance was explained by long-term seasonal trends, which captured the growth of ridership during spring and its decline in colder months. Residual variance of 23.2% indicated short-term disruptions, including those related to weather and holidays.

The STL trend component confirms a steady growth in ridership from winter into spring, peaking in early summer and tapering in the final months of the year, also visible in

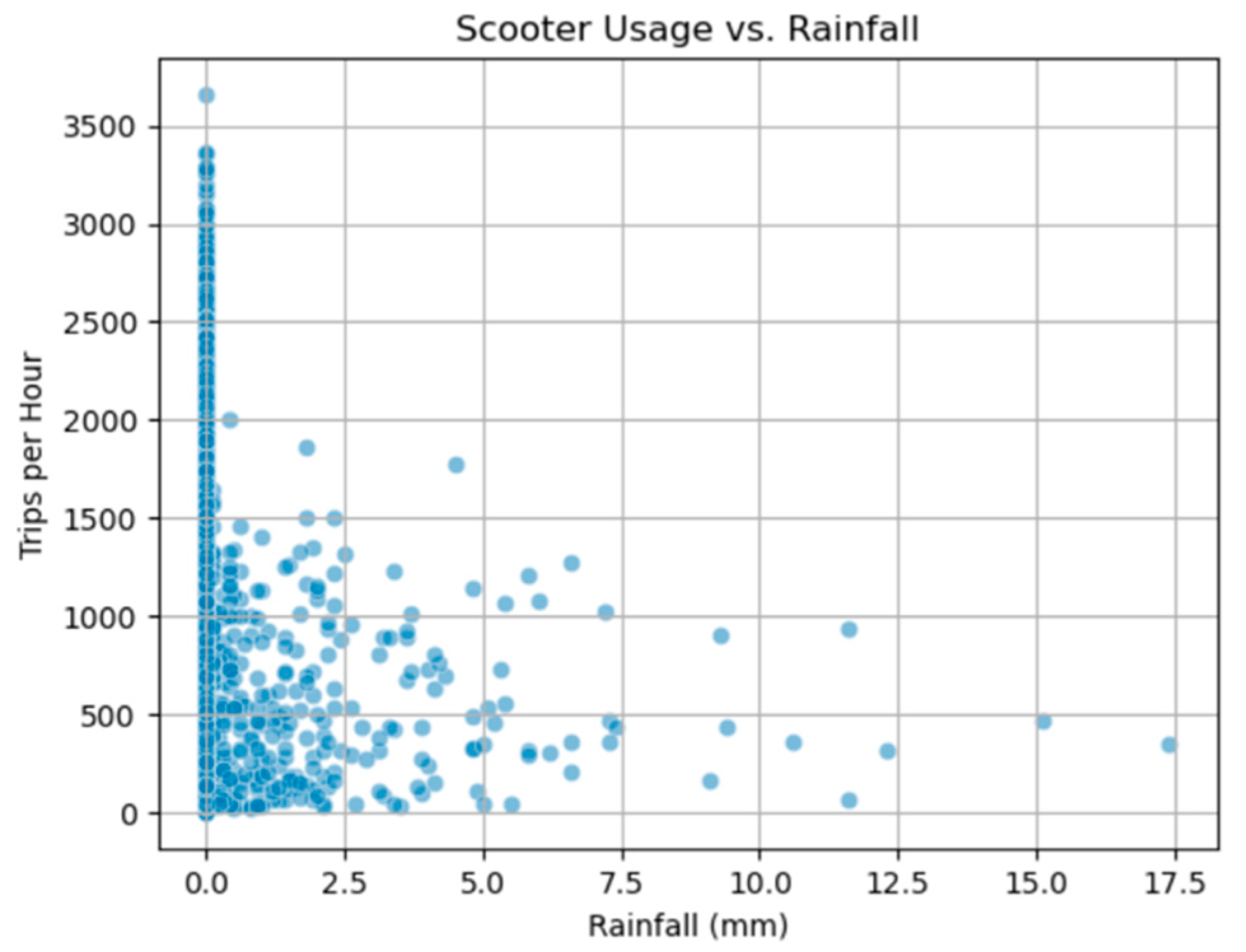

Figure 6. The seasonal component reveals consistent weekly cycles, with lower demand on weekends and holidays, echoing patterns captured by the categorical regressors. Crucially, the residual component indicates demand shocks attributable to unmodeled short-term events, with many aligning temporally to days with rainfall.

As emphasized in

Figure 7, rainfall emerges as the most significant short-term suppressor of demand. Even light rain causes a measurable drop in usage, with trips nearly disappearing once precipitation exceeds 2 mm/h. This confirms the robustness of the negative coefficient observed in the regression model and further validates the responsiveness of scooter demand to real-time weather conditions.

4.3. Spatial Distribution and Accessibility Patterns

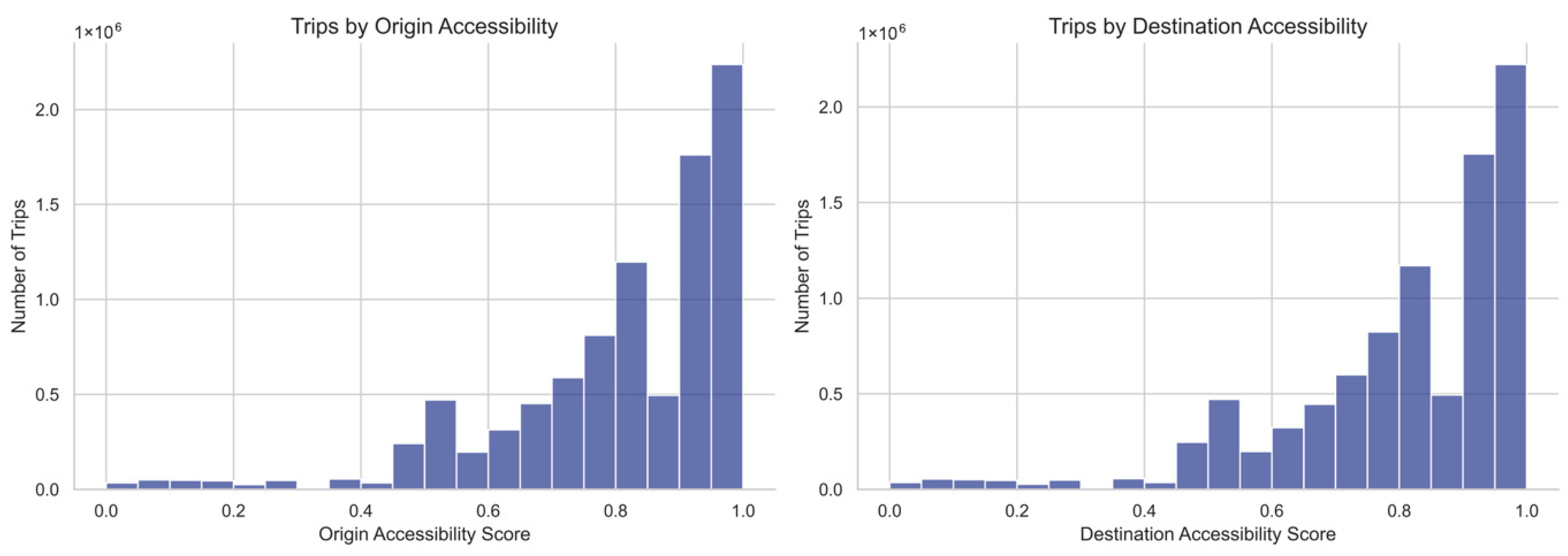

The spatial dimension of e-scooter usage is examined through the lens of public transport accessibility. Trip origins and destinations were matched to a national accessibility index ranging from 0 (no access) to 1 (high access), based on proximity and frequency of bus, rail, and light rail service within a 200 × 200 m grid.

Figure 8 shows that most trips begin and end in highly accessible areas. The distribution is heavily skewed to the right, with accessibility scores above 0.8 dominating. Zones with accessibility below 0.4 are nearly absent from the trip database, suggesting limited service coverage or low latent demand in these areas.

Complementing these histograms, Lorenz curves (

Figure 9) for both origins and destinations bow sharply away from equality, with high Gini coefficients (≈0.59 for each). This confirms that trips are disproportionately concentrated in the highest-accessibility deciles: far above the 10% share each decile would have under a uniform-supply counterfactual and well below that in low-access areas. Together, the distributional and inequality metrics reinforce the conclusion that shared-scooter use clusters in the city’s best-connected zones.

To evaluate directional flows,

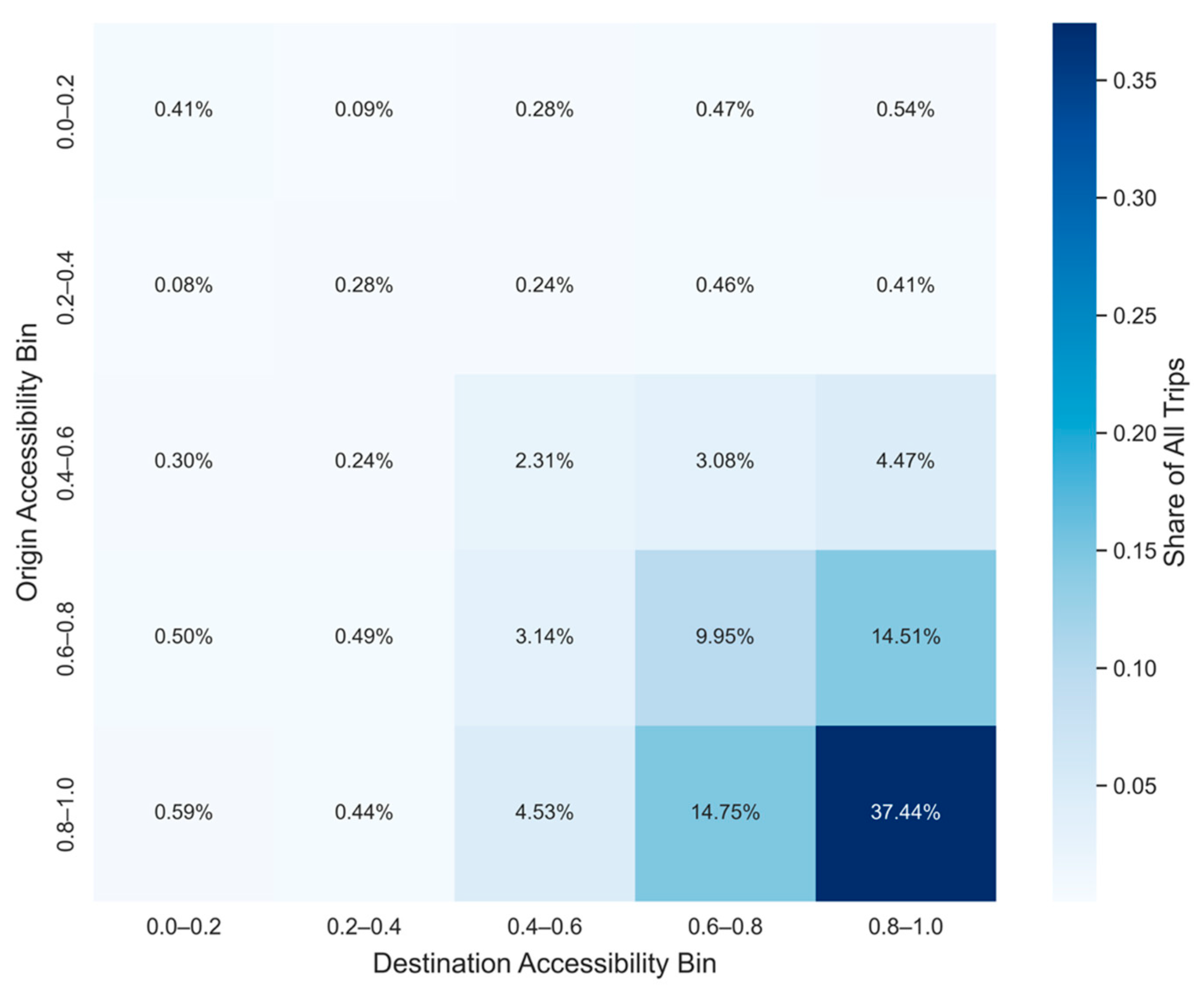

Figure 10 plots the difference between destination and origin scores. The distribution is centred around zero with a slight right skew, indicating that while some trips move toward better-served areas, the majority occur within zones of similar accessibility.

Figure 11 further confirms this pattern. More than 37% of all trips occur between areas in the highest accessibility tier (0.8–1.0 to 0.8–1.0), while trips involving low-access areas account for less than 3% of all movements. The data points to a feedback effect, where high-accessibility areas attract more services, leaving low-access zones underserved and widening spatial disparities.

Figure 12 shows the spatial distribution of shared scooter trips in Tel Aviv, visualized through directional flows between high-frequency origin and destination points. Each line represents a connection between locations with more than 500 trips over the course of the year.

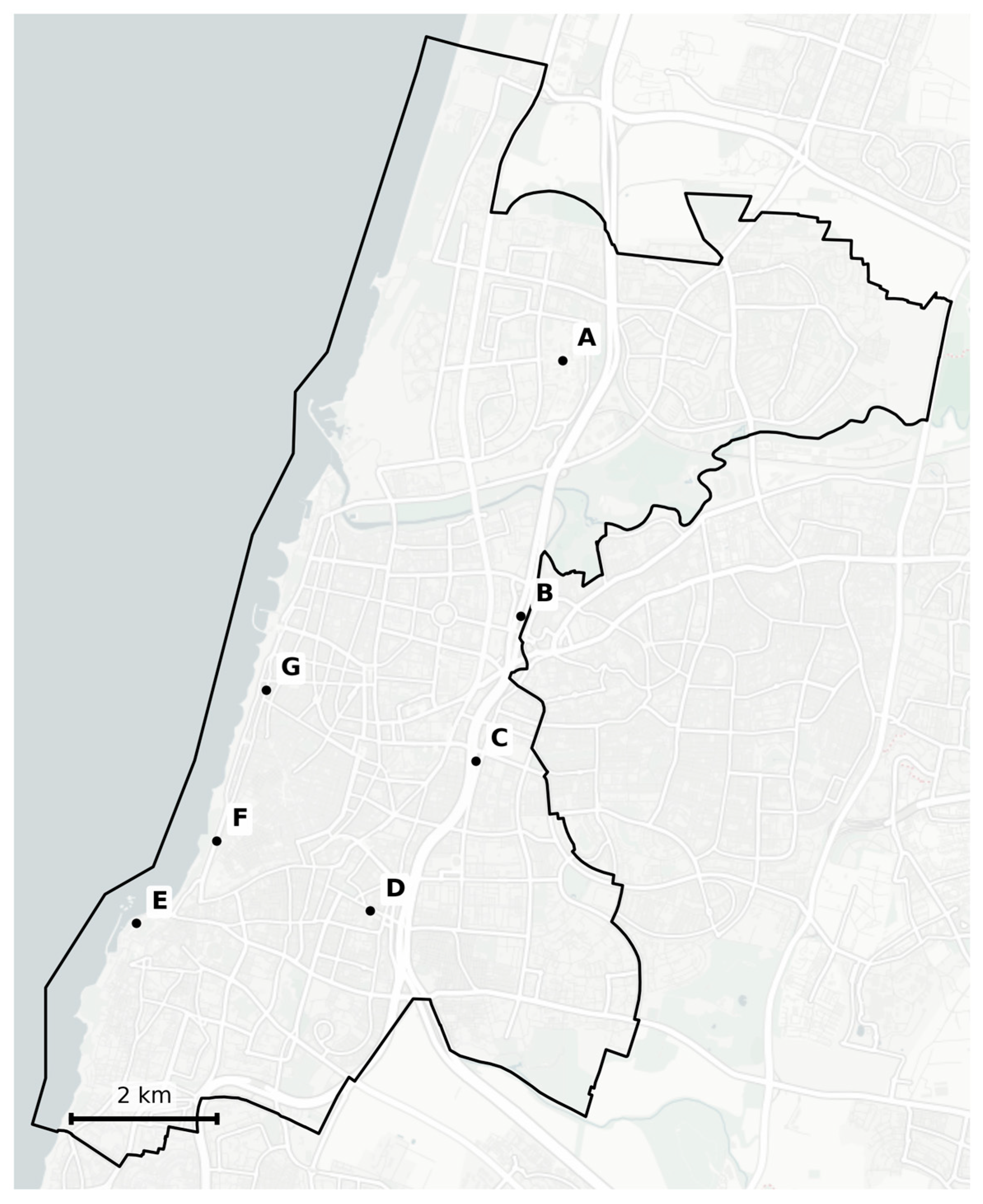

Figure 13 presents the map of Tel Aviv with marked areas of interest.

The visual pattern reveals a highly concentrated usage core in central Tel Aviv, with high-usage areas clustered around dense, mixed-use neighbourhoods and major multimodal hubs such as HaShalom (C) and Savidor train stations (B), as well as Tel Aviv University (A). Strong directional connections are observed between these areas and key transportation nodes. HaShalom station links directly to the Yigal Alon business corridor, while Savidor station, combined with a central bus terminal (D), facilitates east–west movements across the city’s core. This area is characterized by a high concentration of public services, offices, shops, and cafés. Numerous movements are also observed along the seaside promenade (G), a major recreational corridor supporting walking, cycling, and scooter riding, with flows branching southward to Charles Clore Park (F) and eastward to Old Jaffa (E). In the city centre, the dense web of origins and destinations reflects the intensity of commercial and social activity. Additional significant flows originate from the eastern periphery toward the urban heart, aligned with the city’s rail access along the Ayalon Highway. A pronounced north–south axis is also evident along Ibn Gabirol, King George, and Dizengoff Boulevards, which serve as primary internal corridors. Notably, the directional arrows mostly connect zones within this high-accessibility core, with relatively few links extending outward to peripheral or underserved neighbourhoods.

This suggests that shared e-scooters are not predominantly used for first- or last-mile connections to transit from underserved areas. Instead, trip flows are short, dense, and largely internal to the most accessible zones, indicating a behavioural pattern more aligned with substituting walking trips within central urban areas. While some scooter use may support multimodal transfers near major stations, the dominant spatial logic points to local, intra-core circulation rather than an increase in accessibility.

5. Discussion

The results of this study reveal that shared e-scooter usage in Tel Aviv is shaped by an interplay of temporal routines, environmental factors, and spatial accessibility. Temporal patterns follow the city’s institutional rhythms: weekday commuting drives peak demand, while weekends introduce leisure-oriented behaviour with later usage peaks. The distinction of Thursdays underscores the cultural specificity of mobility, as demand intensifies ahead of the weekend. Weather sensitivity, especially the decline in usage during rainfall, demonstrates the vulnerability of micromobility systems to environmental disruption and highlights the need for responsive operations and user communication. These findings imply that scooter usage is highly forecastable, with routine-driven behaviour offering clear signals for system planning. The afternoon peak, consistent across seasons, reflects Tel Aviv’s workday structure, while the flattening and delay of weekend activity reveal a behavioural shift toward leisure-based travel. Notably, the higher usage observed in spring and summer suggests that warmer months invite greater outdoor activity, both among residents and tourists. This seasonality underscores the recreational dimension of shared micromobility and the city’s attractiveness during holiday periods.

The cultural context amplifies these patterns. The pre-weekend surge on Thursdays reflects a rhythm where socializing and early weekend activities begin before the formal workweek ends. Holidays also register strongly in the data, not simply as periods of low usage but as behavioural resets, when normal patterns collapse, and alternative travel needs arise. Together, these insights highlight the need for dynamic scheduling of rebalancing and maintenance operations. A system attuned to daily, weekly, and seasonal fluctuations can reduce costs and downtime while improving user satisfaction and multimodal integration.

The spatial distribution of demand further reinforces the selective nature of shared e-scooter usage in Tel Aviv. Despite the inclusion of peripheral neighborhoods within the formal service area, actual trip activity is overwhelmingly concentrated in central, high-accessibility zones. Trip origins and destinations are clustered in areas already well served by public transport and urban amenities, while low-accessibility districts remain significantly underutilized within the operational footprint of shared micromobility. This pattern is not attributable to service restrictions, but to deeper structural, infrastructural, and perceptual barriers that inhibit adoption in peripheral zones. The absence of trip flows connecting low- and high-accessibility areas, combined with the symmetry of short-range movements within central zones, suggests that shared e-scooters are not currently functioning as first- or last-mile connectors in any consistent or systemic way. Instead, they appear to serve a different function: offering flexible alternatives to walking or cycling for short, intra-neighbourhood travel among those already embedded in the core urban fabric. The narrow distribution of Δaccessibility values and the lack of directional flow from peripheral areas underscore the degree to which these services are reinforcing existing spatial hierarchies in mobility access.

These findings carry clear implications for the governance of shared micromobility. If left to market forces alone, deployment strategies will continue to prioritise areas of dense demand and high turnover, thereby intensifying spatial inequities. Policy interventions must therefore extend beyond ensuring fleet availability and instead address where and for whom these services are genuinely usable. Licensing frameworks can incorporate minimum service obligations across diverse accessibility tiers, while financial incentives, such as per-trip subsidies or geofenced bonuses, may be necessary to catalyse demand in underserved locations. Simultaneously, investment in supportive infrastructure (e.g., dedicated lanes, secure parking, lighting) in peripheral areas is critical to lower perceived barriers and enhance safety.

In summary, while shared e-scooters hold strong potential as an agile, low-carbon transport mode, their success in promoting sustainable and inclusive urban mobility depends not only on technological flexibility or operational efficiency, but on deliberate design and governance. Without targeted regulation, shared micromobility risks reproducing existing spatial inequalities rather than expanding meaningful access. These findings underscore the importance of aligning deployment strategies with broader planning objectives, ensuring that emerging mobility solutions actively contribute to equity and connectivity, rather than simply reflecting patterns of privilege already embedded in the urban fabric.

6. Conclusions

This study analysed a full calendar year (2024) of shared e-scooter trip data in Tel Aviv with over 9 million reconstructed trips from all licensed providers. We combined these records with weather data and a high-resolution spatial index of public transport accessibility. The methods used included multivariate regression to assess temporal and environmental drivers of demand, seasonal-trend decomposition to capture recurring patterns, and geospatial analysis to examine where scooters are used and whether they extend access to underserved areas.

Findings show that scooter usage is strongly shaped by institutional rhythms and weather. Demand peaks in the afternoon, drops during holidays and rain, and increases notably on Thursdays, aligning with cultural routines in Tel Aviv. Usage patterns follow predictable cycles, confirming that shared scooters are integrated into the city’s temporal structure. Spatially, however, usage is concentrated in central, well-connected areas. More than a third of trips occur within zones already ranked highest for accessibility, while low-access areas are barely present in the data. There is little evidence that scooters serve as first- or last-mile connections from underserved neighbourhoods. Instead, they are primarily used for short, flexible trips in already highly accessible areas, often substituting walking or short bike rides. Rather than expanding access, the current deployment reinforces existing mobility hierarchies.

The main limitation of this study is the absence of user-level data. Without knowing who uses scooters or for what purpose, we cannot evaluate their role in broader travel chains. Additionally, the dataset was anonymized so no information about the operator and price was available, which prevented any assessment of affordability or its impact on usage patterns. The dataset also did not include energy consumption metrics, which limits the analysis of environmental impacts. Another constraint is the absence of information on competing modes: we cannot definitively determine whether scooter trips replaced car, public transport, walking, or cycling. While we can reasonably speculate, based on trip length, spatial clustering, and usage timing, that many scooter trips likely substituted for walking or short bike rides rather than car travel, any stronger modal attribution would require data beyond what the current structure allows. A further limitation is that we cannot observe dynamic pricing, for example, an increase with demand surges or short-lived promotions. These unobserved commercial levers may co-vary with weather, the calendar, and demand, potentially amplifying or dampening the temporal patterns we estimate.

Future research should integrate user surveys or app-based mobility tracking to explore trip purposes, multimodal connections, and barriers to adoption. Modal substitution studies, in particular, would help assess whether shared scooters reduce car usage or simply displace more sustainable modes like walking. Further research should analyse how pricing, including dynamic adjustments, promotions, and surge periods, affects demand patterns and equity outcomes.

Author statement: The views expressed here are those of the authors and may not, under any circumstances, be regarded as an official position of the European Commission. Mention of trade or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the authors or the European Commission.