1. Introduction

The complexity of contemporary transport and logistics arises from rapid urbanisation, tightly coupled global supply chains, and ambitious decarbonisation targets. This complexity results in computationally intensive tasks for processing large volumes of data and/or considering large decision spaces to make optimal choices. Classical optimisation approaches, ranging from mixed-integer programming [

1] to metaheuristic search [

2], perform well on narrowly scoped or static tasks, but struggle to deliver near-optimal decisions within the stringent temporal horizons required for city-scale vehicle routing, adaptive traffic control, or same-day fulfilment [

3].

Quantum computing represents a fundamentally different computational paradigm that exploits superposition, entanglement, and interference to accelerate the exploration of vast combinatorial spaces [

4]. In classical computing, information is processed using bits that exist in one of two states: 0 or 1. Quantum computing uses quantum bits, or qubits, which can exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 at the same time. This means that a quantum computer can explore many possible solutions simultaneously, rather than one at a time. Entanglement is another key principle, a quantum phenomenon in which qubits become linked in such a way that the state of one qubit instantly influences the state of another, no matter how far apart they are. This allows quantum computers to coordinate and correlate information across qubits in ways that classical systems cannot replicate. Finally, quantum interference is used to amplify the probability of correct solutions while cancelling out incorrect ones. By carefully orchestrating how quantum states evolve and interact, quantum algorithms can guide the system toward the most promising answers in a vast search space. Together, these properties enable quantum computers to accelerate the exploration of vast combinatorial spaces, such as those found in cryptography, optimisation, drug discovery, and materials science. In all these domains, the number of possible configurations grows exponentially and quickly overwhelms classical computing resources. Quantum computing is a rapidly progressing area, with recent breakthroughs making it more accessible to the user. Although quantum architecture is not widely available, research into the use of Quantum computers tends to focus on adopting and exploiting specific aspects of the architecture or underlying science.

There are three lines of technological development that are particularly relevant for transport optimisation: quantum annealing hardware that directly solves binary quadratic models [

5], variational circuits executed on noisy intermediate-scale quantum processors [

6], and quantum-inspired architectures that emulate tunnelling effects by means of complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor hardware [

7]. Collectively, these platforms have produced promising results for logistics problems such as vehicle routing [

8,

9], supply chain planning [

5], network design [

10], and plug-in vehicle charging [

11], although virtually all empirical demonstrations remain confined to proof-of-concept instances [

12,

13].

Despite this promise, quantum optimisation in transport is still distant from routine deployment. Current devices possess fewer than one hundred logical qubits, suffer from limited connectivity and modest gate fidelity that is not yet at the level required for fault-tolerant computation [

14,

15], and rely on software toolchains that remain immature [

16]. An independent energy audit experiment even reports that small quantum workloads can consume more electricity than a conventional desktop workstation [

17]. Operational impediments intensify these technical constraints: most published case studies use synthetic or down-sampled data, none measure queue latency for cloud-hosted processors, and pilot-scale deployments have yet to appear in the academic record. Institutional factors add further inertia because organisations face shortages of interdisciplinary talent, encounter uncertain return-on-investment, and confront a near-absence of sector-wide benchmarks or standards [

18,

19,

20].

The existing literature is fragmented. Theoretical articles focus on overcoming technical challenges to improve performance while neglecting the modelling effort required for real-world integration, whereas experimental reports highlight isolated performance gains without systematically evaluating their generalisability, energy cost, or organisational feasibility. Therefore, a comprehensive synthesis that unites empirical performance evidence with the multifaceted barriers that govern technology diffusion is essential. Such a synthesis can clarify the readiness for quantum optimisation for transport applications, expose research gaps that warrant priority, and inform policy aimed at responsible adoption.

This study conducts a systematic review of peer-reviewed work published between 2015 and June 2025. Fifteen peer-reviewed journal articles satisfy the inclusion criteria after exclusions for narrative reviews, non-transport domains, and weakness in methodological weakness. The review catalogues their problem settings, quantum techniques, dataset scales, comparative baselines, and methodological quality, then interprets these findings in terms of technical, operational, and institutional barriers. By integrating quantitative evidence with qualitative insight, the study seeks to clarify the current state of quantum optimisation in transport, identify the most pressing research gaps, and outline a structured agenda for future investigation and pilot implementation. The novel contributions of this article are as follows:

It is the first systematic review of quantum computing applications in transportation, mapping out key problem domains (such as vehicle routing, scheduling, and traffic control), and quantum techniques used.

It identifies the major barriers to adoption, including hardware limitations, lack of real-world data, energy inefficiency, and organisational challenges.

It proposes a structured research agenda to bridge the gap between laboratory studies and real-world deployment, emphasising the need for pilot trials, open benchmarks, and robust evaluation protocols.

This review focuses specifically on optimisation problems within transport and logistics (e.g., routing, scheduling, network design, traffic control), rather than the full breadth of quantum applications in travel demand modelling or quantum cognition. Nevertheless, we acknowledge emerging quantum approaches to demand-side modelling (e.g., quantum discrete choice, quantum cognition) and briefly map these to highlight how optimisation fits within the broader transport-quantum landscape.

Several prior surveys have reviewed quantum optimisation and quantum annealing in broader operations-research or process-systems contexts (e.g., [

21,

22]). However, these works are conceptual or method-oriented rather than transport-specific, and they do not synthesise empirical performance metrics, energy use, queue latency, or organisational readiness. In contrast, the present review undertakes a PRISMA-guided synthesis that focuses specifically on measured empirical evidence for quantum and quantum-inspired optimisation in transport and logistics.

To our knowledge, no prior transport-focused review systematically aggregates empirical findings on quantum and quantum-inspired optimisation—particularly regarding energy footprint, queue latency, hardware constraints, and organisational readiness—which further motivates the need for this synthesis.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 introduces the relevant transport optimisation problems, summarises quantum computing methods, and presents the barrier taxonomy that motivates the review.

Section 3 describes the review protocol and the quality assessment procedure.

Section 4 synthesises the empirical results of the fifteen primary studies, while

Section 5 discusses implications, limitations, and priorities for future work. Finally, a conclusion is provided in

Section 6.

2. Background

2.1. Transport and Logistics Optimisation Problems

Efficient optimisation underpins every operational and strategic layer of modern transport and logistics, ranging from day-to-day vehicle routing choices to long-horizon investment in depots and inventory buffers. Canonical problems in this field include the travelling salesperson problem, the vehicle routing problem and its time window variant, crew and machine scheduling, multi-echelon inventory design, facility location and network expansion planning, adaptive traffic signal control, and fleet-level charging management [

23]. All belong to the class of NP-hard combinatorial problems. The same exponential growth appears when a factory scheduler must allocate dozens of robots to hundreds of jobs or when a planner must choose which of several thousand links to add to a road network.

Because the search space grows explosively with instance size, exact formulations such as mixed-integer programming are overwhelmed once realistic networks, stochastic travel times, or dynamic constraints are introduced [

24]. Meta-heuristics and machine learning surrogates provide usable solutions faster, yet they do so by relinquishing global optimality and, in many cases, stability. This trade-off becomes sharper as urban networks become more dense, customer service windows shrink, and real-time decision cycles shorten [

25,

26].

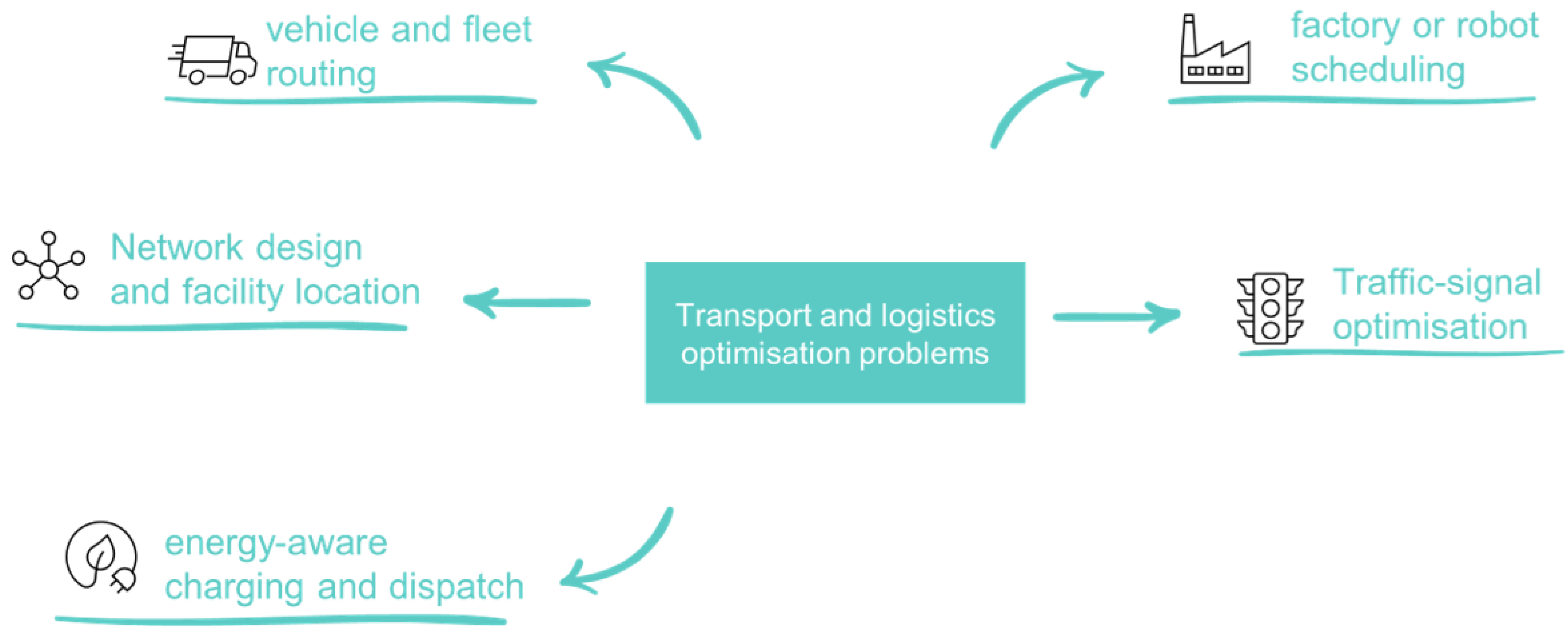

Figure 1 summarises the five problem families most often targeted by quantum optimisation research. There are vehicle and fleet routing, robot and factory scheduling, network design and facility location planning, adaptive traffic signal control, and energy-sensitive charging and dispatch.

Beyond supply-side optimisation, quantum-theoretic perspectives have also begun to influence demand-side transport modelling. Although outside the specific scope of this review, which focuses on optimisation and operational decision-making, a small but growing body of literature explores quantum cognition and quantum-probabilistic approaches to travel behaviour. For example, quantum-utility formulations have been used to interpret traffic-count and perception data through interference-based probability structures [

27], while quantum-probabilistic models have been applied to path-choice behaviour in small transport networks [

28]. These studies address behavioural modelling rather than operational optimisation and therefore do not meet the inclusion criteria of this review, but they illustrate the broader emergence of quantum-based thinking across multiple layers of transport research.

In parallel with these conceptual developments, several recent studies illustrate the growing methodological interest in quantum and quantum-inspired optimisation within transport and logistics. Examples include a comprehensive 2025 review of quantum annealing technologies for transportation optimisation in quantum information processing [

29]; quantum-assisted traffic routing and electric-vehicle charging scheduling using VQE-based architectures [

30]; intelligent traffic-management optimisation using quantum-theoretic and randomisation-based consensus models [

31]; quantum-annealing-based optimal control of traffic signals [

32]; and integrated network-design and vehicle-routing formulations for road-transport systems [

33]. These works provide additional context for the breadth of emerging transport-oriented applications of quantum methods and complement the empirical optimisation studies synthesised later in this review.

2.2. Quantum Computing: Principles and Methods

Quantum computing offers a fundamentally different approach to computation by representing information in qubits. Unlike binary digits in classical computation systems, qubits can exist in a combination of 0 and 1 at the same time. This phenomenon is known as superposition, and it allows quantum computers to explore many possible solutions simultaneously. Additionally, qubits can be entangled, meaning that the state of one qubit is directly related to the state of another, even if they are far apart. This entanglement, along with quantum interference, enables quantum computers to perform certain calculations much more efficiently than classical computers by narrowing down the correct answers from a vast number of possibilities in a single step [

4,

34].

Many transport optimisation problems can be expressed in a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimisation (QUBO) [

35] form:

where

is a vector of

n binary decision variables (e.g., vehicle–customer assignment),

encodes quadratic interaction penalties, and

represents linear costs.

QUBO models map directly to an Ising Hamiltonian [

36] by substituting

, where

is a spin variable:

Here, denotes the vector of spin variables, and is the Ising energy (Hamiltonian) associated with a given spin configuration, with indices running over the n decision variables. The coefficients and are directly derived from the corresponding QUBO parameters. This mapping enables routing, scheduling and network-design tasks to be encoded as energy-minimisation problems on a quantum annealer.

There are two hardware paradigms that dominate in current research:

Quantum Annealers: These machines, such as those built by D-Wave Systems, are designed to solve optimisation problems where the goal is to find the best solution among many possible options. They do this by representing the problem as a mathematical model called an unconstrained binary quadratic model and then using a quantum process called tunnelling to guide the system toward the lowest-energy (or most optimal) configuration [

37]. This approach is particularly useful for problems like scheduling, logistics, and machine learning.

In quantum annealing, the system evolves from an initial Hamiltonian

with a known ground state to a problem Hamiltonian

that encodes the optimisation objective

Here, is the time-dependent Hamiltonian and is a monotone annealing schedule that interpolates between and , increasing smoothly from 0 to 1 during the anneal. Ideally, the system remains in (or near) the ground state of , yielding a high-quality solution.

Gate-Based Quantum Processors: These are more general-purpose quantum computers, developed by companies like IBM and Rigetti. They work by applying a series of quantum operations, called unitary gates, to qubits in a controlled sequence, similar to how classical computers use logic gates. These processors can run sophisticated algorithms such as the Quantum Approximate Optimisation Algorithm (QAOA) [

38], which is used to solve complex optimisation problems.

Gate-based quantum processors often implement QAOA [

38], which alternates between application of the problem Hamiltonian

and a Hamiltonian mixer

:

Here, p denotes the number of alternating QAOA layers, are real-valued variational parameters, + = (0 + 1)/ is the single-qubit equal-superposition state, and n is the number of qubits.

These parameters are updated by a classical optimiser to minimise the expected cost

where

encodes the constraint and cost structure of the transport optimisation task (e.g., delivery-tour sequencing or assignment decisions).

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [

39], which is useful for simulating molecular structures and quantum systems through sequences of parameterised quantum gates compiled by toolchains such as Qiskit [

40,

41,

42].

VQE uses a parametrised quantum circuit (ansatz) to approximate the ground state of an optimisation Hamiltonian [

39]:

where

consists of layers of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates, and

is the vector of trainable circuit parameters. The reference state

denotes the all-zero

n-qubit initialization. A classical optimiser updates

to minimise the expected energy

Here denotes the problem Hamiltonian that encodes the objective and feasibility constraints of the transport optimisation task. Logarithmic-qubit encodings for transport-routing tasks reduce qubit requirements by compressing location or sequencing indices into compact binary representations within the ansatz.

A third category, known as quantum-inspired digital annealers, offers a bridge between classical and quantum computing. These systems are built using conventional computer hardware (such as CMOS chips), but they mimic certain quantum behaviours, especially tunnelling, using carefully designed algorithms [

43]. Although they are not true quantum computers, they use similar mathematical models (such as the Ising model [

36]) and can serve as practical tools to solve problems while quantum hardware continues to mature [

44]. The Ising model [

36,

45] is a simplified mathematical model used in statistical physics to study phase transitions, where each point on a lattice represents a magnetic spin that can be in one of two states (up or down), interacting with its neighbours and possibly an external magnetic field.

To make quantum computing more accessible and scalable, researchers are also developing compiler frameworks to help translate high-level tasks into quantum operations. An example is the ‘Naginata’ circuit synthesiser, which automates the design of reusable quantum circuit blocks, particularly for tasks in machine learning [

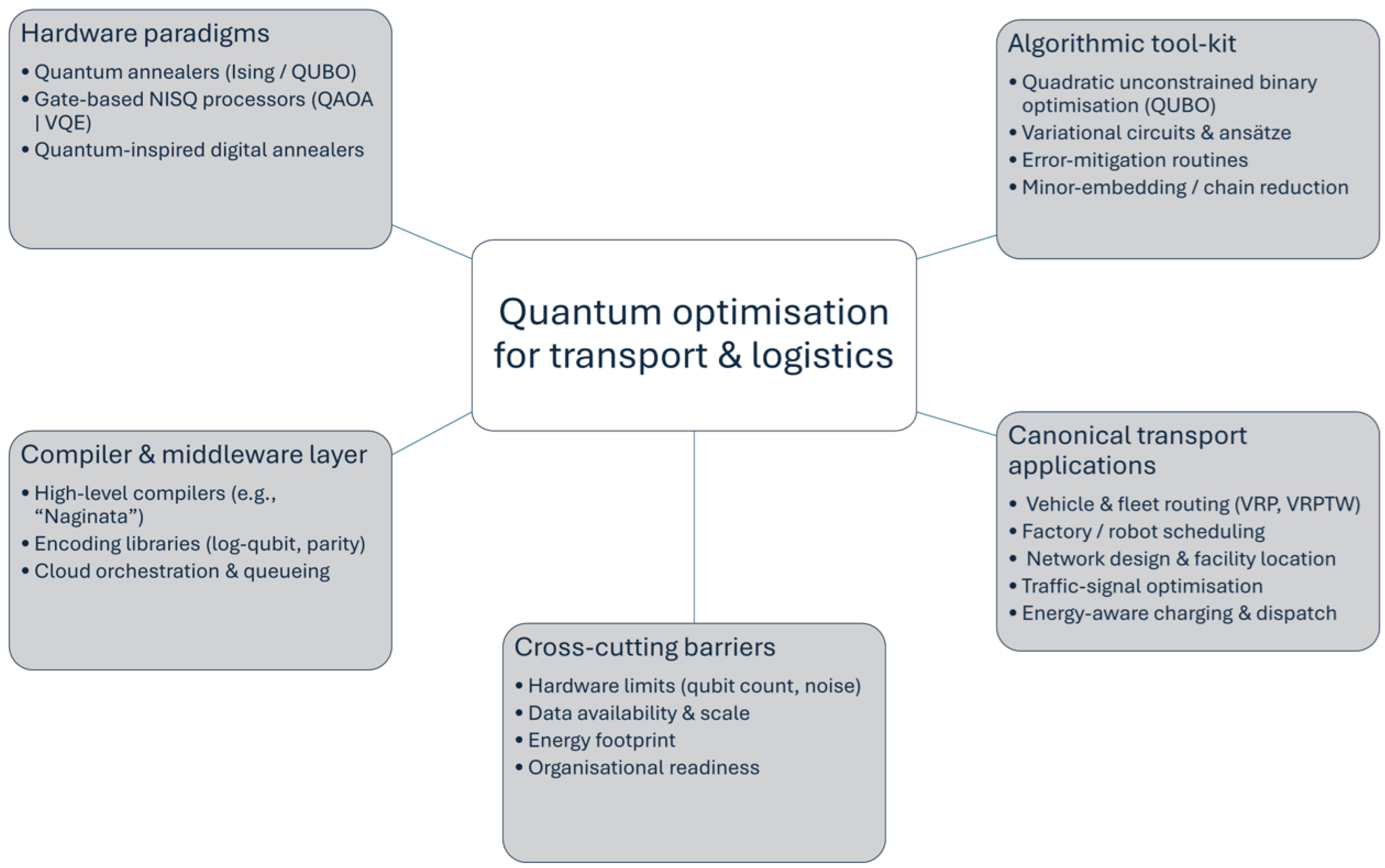

46]. These tools are essential for building more complex quantum applications and making quantum computing usable by a broader range of developers and researchers. These interdependencies are visually brought together in

Figure 2, which shows how hardware, algorithms, software infrastructure, application domains, and adoption barriers constitute an integrated ecosystem for quantum optimisation in transport and logistics.

2.3. Quantum Cognition and Quantum-Probabilistic Demand-Side Models

Although this systematic review focuses exclusively on optimisation-orientated applications of quantum and quantum-inspired computation in transport and logistics, it is important to recognise that quantum-theoretic approaches have also begun to influence demand-side transport modelling. These studies lie outside the inclusion criteria of the present PRISMA protocol, as they do not involve empirical optimisation or measurable computational performance. However, they illustrate how quantum perspectives are emerging across multiple layers of transport analysis.

One stream applies quantum cognition and quantum probability to represent behavioural uncertainty, contextual interference effects, and non-classical substitution patterns in travel behaviour. For example, quantum-utility formulations have been used to interpret traffic count and perception data through probability amplitude structures (e.g., [

27]). Related work has also demonstrated how quantum cognition can bridge stated-preference and revealed-preference data, providing an alternative probabilistic foundation for modelling travel choices (e.g., [

47]). More recent work explores quantum-probabilistic path-choice models in small transport networks, demonstrating how interference terms can capture route-selection preferences beyond classical random utility maximisation (e.g., [

28]).

Additional conceptual studies have introduced quantum-based enhancements to discrete-choice modelling frameworks, showing how superposition and phase parameters may encode preference ambiguity, context dependency, or order effects that are not easily handled by multinomial logit or nested-logit structures. This includes early demonstrations published in Transportation Research Part B and related outlets on quantum decision-making, quantum cognition, and hybrid quantum–classical behavioural representations.

Although these contributions do not address optimisation problems such as routing, scheduling, or network design and therefore fall outside the empirical dataset reviewed in this study, they highlight the breadth of quantum-theoretic developments underway in transportation research. Their presence reinforces the rationale for focusing the present systematic review specifically on operational optimisation, where quantum and quantum-inspired techniques currently offer the most concrete, measurable, and computationally testable applications.

2.4. Quantum Computing Applications in Transport and Logistics

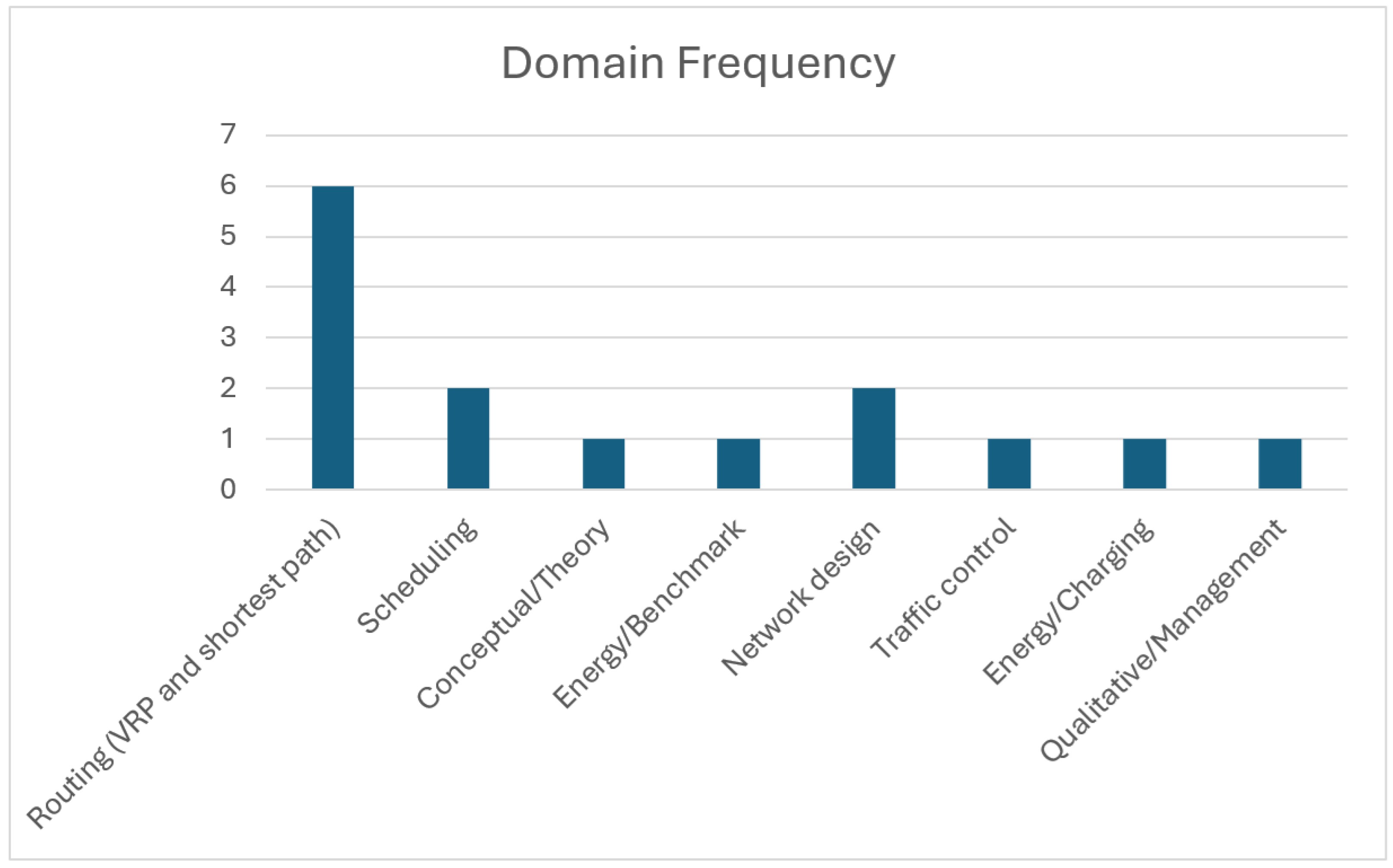

Research conducted over the past five years shows a clear thematic pattern, as seen in

Table 1. We refer to these as “problem families” because each group corresponds to an established class of NP-hard optimisation problems in transport and logistics that share a common mathematical formulation and typical constraint patterns. Treating them as families therefore reflects both their historical treatment in the operations-research literature and their shared suitability for quantum optimisation approaches.

Approximately half of the empirical corpus is focused on vehicle and fleet routing. These studies employ either Ising formulations solved on quantum annealers or logarithmically encoded variational circuits executed on simulators. Factory and robot scheduling problems form a second cluster that exploits quantum-inspired digital annealing or hybrid variational approaches. A smaller but conceptually important group addresses challenges in network design and supply chain location with hybrid quantum-classical improvement loops, while some work explores traffic signal timing and plug-in vehicle charging. Across all domains, quantum annealing remains the most frequently adopted technique because the binary nature of the transport decision variables lends itself to Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimisation (QUBO); variational circuits appear mostly in proof-of-concept simulators, whereas quantum-inspired annealers provide an intermediate step that already scales to thousands of decision variables.

2.4.1. Vehicle and Fleet-Routing Problems

Routing problems in transport and logistics involve determining how one or more vehicles should visit a set of delivery points while minimising total travel distance, time or cost, and satisfying operational constraints. In last-mile delivery, vehicles typically start from a depot, serve a set of geographically dispersed customers, and return once their assigned deliveries are completed. Real-world distribution networks include additional requirements, such as limited vehicle capacity, customer-specific delivery windows, maximum route durations, and the need to manage traffic congestion or depot imbalance. These elements make routing tasks highly combinatorial, especially in dense urban environments where delivery schedules are tight and service expectations are time-critical. This subsection provides contextual grounding only and does not attempt a full review of the classical VRP literature, which lies outside the optimisation-focused quantum scope of this study.

Classical benchmark datasets, such as the widely used Solomon time-window instances [

59], illustrate the practical features of real delivery networks, including spatial clustering of customers, heterogeneous service times, and varying delivery windows. These benchmarks are frequently used to demonstrate how routing complexity grows as more delivery points and constraints are added, and they provide a useful contextual reference for understanding the types of delivery-tour structure that quantum optimisation methods aim to address.

Quantum and quantum-inspired optimisation approaches build on these classical routing structures by encoding sequencing, assignment, and feasibility relationships into binary formulations compatible with quantum hardware. QUBO representations [

35] and the corresponding Ising mappings [

36] offer a structured way to express which customers a vehicle should serve and in what order. Once encoded, these routing tasks can be explored by annealing-based devices, which search for low-energy configurations, or by gate-based variational algorithms, which use parameterised quantum circuits to navigate large solution spaces. Such approaches offer the potential to evaluate many routing alternatives in parallel, supporting faster or more efficient decision processes in operational last-mile logistics.

2.4.2. Factory and Robot-Scheduling

Modern distribution centres and production warehouses increasingly deploy fleets of automated guided vehicles (AGVs) in tandem with fixed robotic workstations. Each vehicle must collect materials, deliver them to the correct station, and sometimes perform intermediate processing steps while sharing aisles and transfer points with other vehicles. If two AGVs attempt to enter the same aisle segment or workstation simultaneously, they risk collision; even without physical contact, they can mutually block access routes and immobilise the fleet, a state of the system commonly referred to as deadlock [

60]. Throughput targets, battery constraints, task precedence relations, and machine eligibility rules further complicate the scheduling landscape. When these spatial and temporal restrictions are modelled in full detail, the schedule usually takes the form of a disjunctive graph or a time-indexed integer program. Such formulations generate NP hard sequencing and routing subproblems that classical branch-and-bound or constraint programming solvers can handle only for relatively modest instance sizes [

61].

Quantum and quantum-inspired methods are attractive because many of the underlying decisions are binary (e.g. vehicle i uses segment j at time t; job k assigned to machine m) and can therefore be encoded in the form Ising or the quadratic unconstrained binary optimisation (QUBO) [

62]. Digital annealers already handle tens of thousands of binary variables in near-real time for shop floor-style benchmarks [

54], and hybrid variational/metaheuristic schemes have shown multi-objective improvements in simulated AGV scheduling environments [

55]. Looking ahead, error-mitigated QAOA variants that combine shallow quantum circuits with classical repair heuristics could reduce makespan and congestion while enforcing collision-free and deadlock-free movement plans in high-density automated warehouses.

However, several practical barriers remain. First, data-availability and scaling constraints arise because real AGV-scheduling datasets include fine-grained aisle-occupancy logs, machine-availability calendars, and second-by-second AGV telemetry. These are data points that are often proprietary and require extensive preprocessing before they can be represented as QUBOs. Second, embedding overhead and qubit limits currently prevent full-scale industrial layouts from being encoded without aggressive simplifications. Third, energy consumption and queue latency make cloud-based quantum execution unsuitable for real-time AGV conflict resolution, where decisions often need to be refreshed every few seconds. Finally, organisational readiness, including integration with warehouse-management systems and risk-averse safety protocols remains a key barrier to deploying quantum-enabled scheduling in operational automated-warehouse settings.

2.4.3. Network-Design and Supply-Chain Location

Strategic design questions in freight distribution often require deciding which depots to open, which links to upgrade, and how to size intermediate facilities so that flows can be routed at minimum cost subject to capacity, service time, and reliability constraints [

63,

64]. These problems mix large numbers of binary location variables with non-linear or multi-commodity flow constraints; even with relaxations, standard branch-and-bound and Benders decomposition procedures deteriorate rapidly once network size exceeds a few hundred candidate sites or when multiple demand scenarios are considered.

Quantum annealing offers a compact way to evaluate many facility configurations in parallel because the upper-level location choices can be represented as spins in an Ising energy landscape. Flow costs and interaction penalties map to pairwise couplers, and hybrid loops can call on a classical solver to re-optimise flows for each sampled configuration. Early experiments in the transport literature report sub-percentage optimality gaps relative to the tuned tabu search on benchmark transport network design instances [

56] and demonstrate prototype annealing encodings for additional location expansion scenarios [

10]. Although present hardware limits constrain the scale of these demonstrations, this approach suggests a shorter design iteration cycle for capital-intensive infrastructure planning once larger quantum or quantum-inspired platforms become available.

However, several barriers currently restrict deployment. First, data availability and workflow constraints arise because full network design models require multilayer origin–destination matrices, scenario-specific reliability data, and cost-flow coefficients that are often proprietary or inconsistently formatted across logistics operators. Converting these datasets into QUBO form involves significant preprocessing and dimensionality reduction. Second, hardware limitations, including sparse connectivity, qubit-capacity ceilings, and long embedding chains currently prevent representing full multi-commodity or scenario-based formulations without drastic simplification. Third, energy consumption and queue latency become significant limiting factors, since evaluating thousands of candidate infrastructure plans requires repeated sampling, making cloud access QPUs unsuitable for real-time strategic planning. Finally, organisational readiness issues, such as integration with long-term capital planning processes, regulatory oversight, cybersecurity, and vendor lock-in concerns pose additional challenges before quantum-enabled network-design tools can be adopted in operational logistics environments.

2.4.4. Traffic-Operations Optimisation

Traffic control strategies such as adaptive traffic lights, lane reversals, and ramp metering often use mixed-integer programming models that must be solved every 30–60 s. To make this work in real time, these models usually compromise on finding the best overall solution or coordinating the whole network.

By converting traffic signal timing decisions into a QUBO format, quantum annealers can quickly explore thousands of possible timing plans in parallel [

65]. If data input delays and system response can be reduced, quantum solvers have the potential to improve both local and global traffic optimisation in real-time urban networks.

Several barriers currently limit the practicality of this approach. First, traffic management depends on high-frequency detector data, turning counts, and signal-phase measurements that are often incomplete or inconsistently formatted across jurisdictions. Preprocessing these data into QUBO form adds latency and can reduce the effective resolution of the optimisation. Second, present quantum hardware capacity restricts the size of intersections or corridors that can be modelled without aggressive simplification. Third, real-time signal optimisation is highly sensitive to delay, yet current cloud-based quantum systems introduce queue latency and energy overhead that exceed the few-second decision window typically required for adaptive control. Finally, transport agencies often operate legacy signal-control software, and organisational readiness, procurement constraints, and cybersecurity requirements make it difficult to integrate emerging quantum optimisation tools into operational traffic-management centres.

2.4.5. Energy and Charging Management

Fleet-wide electric vehicle charging, vehicle grid integration, and microgrid scheduling require deciding how much energy to draw (or return) at many sites in many time intervals. The choice made now affects the battery state, network capacity, and feasible choices later, and all of these decisions must adapt to uncertain travel demand and volatile electricity prices. Classical mixed-integer formulations grow rapidly when this uncertainty is explicitly modelled and the solution times deteriorate. Therefore, recent work explores noise-enhanced quantum annealing [

58] and hybrid variational methods [

66] as alternative search engines that can sample complex and irregular cost landscapes more efficiently. These techniques may identify lower-cost charging plans or more resilient dispatch strategies within the short update cycles imposed by dynamic electricity markets.

Across these domains, quantum annealing (QA) is the technique used because binary QUBO formulations naturally map to commonly available hardware. Variational circuits (VQE/QAOA) appear mainly in proof-of-concept simulators, while “quantum-inspired” Ising machines (e.g., Fujitsu DA) bridge the gap with near-real-time performance of thousands of variables.

Energy-management models require high-resolution electricity-price forecasts, transformer-capacity limits, and battery degradation parameters, but such data are often proprietary or noisy. Converting these multi-layer datasets into QUBO form introduces additional preprocessing and aggregation. Hardware limitations also restrict the number of time periods and charging sites that can be represented without severe simplification. Furthermore, energy-management applications require rapid updates during peak-load periods, yet quantum hardware introduces queue latency and high energy overhead, which reduces feasibility for short-cycle decisions. Finally, integration with existing grid-management systems and compliance with safety, cybersecurity, and regulatory requirements means that organisational readiness remains a significant barrier to operational adoption in transport-energy coordination.

2.5. Research Gap and Rationale

Practical experience and the academic record both indicate that quantum optimisation for transport remains immature. Organisations may struggle to recruit professionals who combine quantum algorithm expertise with deep domain knowledge and face significant integration risk because quantum solvers must interoperate with legacy planning systems and ingest real-time telemetry not designed for quantum encodings. Rapid hardware obsolescence and uncertain return on investment further deter deployment, while the absence of sector-wide standards for model formulation, performance reporting, and security compliance adds friction for early adopters. Against this backdrop, the published literature converges on four unresolved gaps that this review seeks to clarify the following:

Statistically robust comparisons: Most studies rely on single-run or best-of-five reporting, making it impossible to quantify variance and replicate results.

Real-time field trials: No paper validates quantum-optimised schedules or signal plans in a live operational environment.

Holistic energy-to-performance analyses: Only one study measures power consumption and none reports queue latency, leaving sustainability and cost–benefit claims unverified.

Hardware readiness beyond laboratory prototypes: Present-generation devices remain at a pre-commercial technology readiness level, with limited qubit counts, sparse connectivity, and rapidly evolving software stacks.

Addressing these gaps will require research that couples algorithmic innovation with workforce development, systematic benchmarking, comprehensive energy and latency audits, and carefully designed pilot deployments.

3. Methodology

This review complies fully with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines. All procedural decisions, including search construction, selection criteria, data extraction protocol, quality assessment, and synthesis plan, were pre-registered and executed without deviation.

3.1. Search Strategy

All bibliographic records were retrieved from Scopus, which provides broad multidisciplinary coverage of both quantum-computing and transport-logistics journals. This review was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) prior to screening and analysis, and the preregistration record is available at

https://osf.io/f8gmj, accessed on 27 June 2025. The search string below was run on 27 June 2025 and was restricted to items published between 1 January 2015 and 27 June 2025. The following Boolean string was applied to title, abstract, and author keywords:

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“quantum computing” OR “quantum algorithm” OR “quantum annealing” OR QAOA OR “quantum-inspired”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“transport” OR “logistics” OR “mobility” OR “freight” OR “routing” OR “supply chain” OR “vehicle scheduling”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“application” OR “implementation” OR “adoption” OR “barrier” OR “challenge” OR “limitation” OR “readiness” OR “feasibility” OR “case study”).

The query returned 158 records. Although Scopus served as the primary index, supplementary searches of Web of Science and IEEE Xplore did not yield additional journal articles that met the inclusion criteria. To ensure completeness, we also screened additional keyword families related to behavioural and demand-side modelling (e.g., “path choice”, “traffic assignment”, “travel demand”, “quantum choice”, “hybrid quantum classical model”). These terms retrieved conceptual or behavioural-modelling studies, but none met the empirical optimisation-focused criteria required for inclusion. All metadata were exported to an Excel workbook that served as a screening log.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria and Screening Procedure

Four inclusion criteria were applied:

The article applied quantum or quantum inspired computation to a transport- or logistics-related optimisation problem and reported empirical findings relevant to barriers, limitations, readiness, or feasibility.

It reported empirical data drawn from numerical experiments, laboratory prototypes, or field cases.

It was a full-length peer-reviewed journal article written in English.

Exclusion criteria eliminated records that focused on physics, chemistry, finance, or genomics; lacked transport relevance; appeared as conference papers, editorials, patents, or preprints; or lacked full-text access.

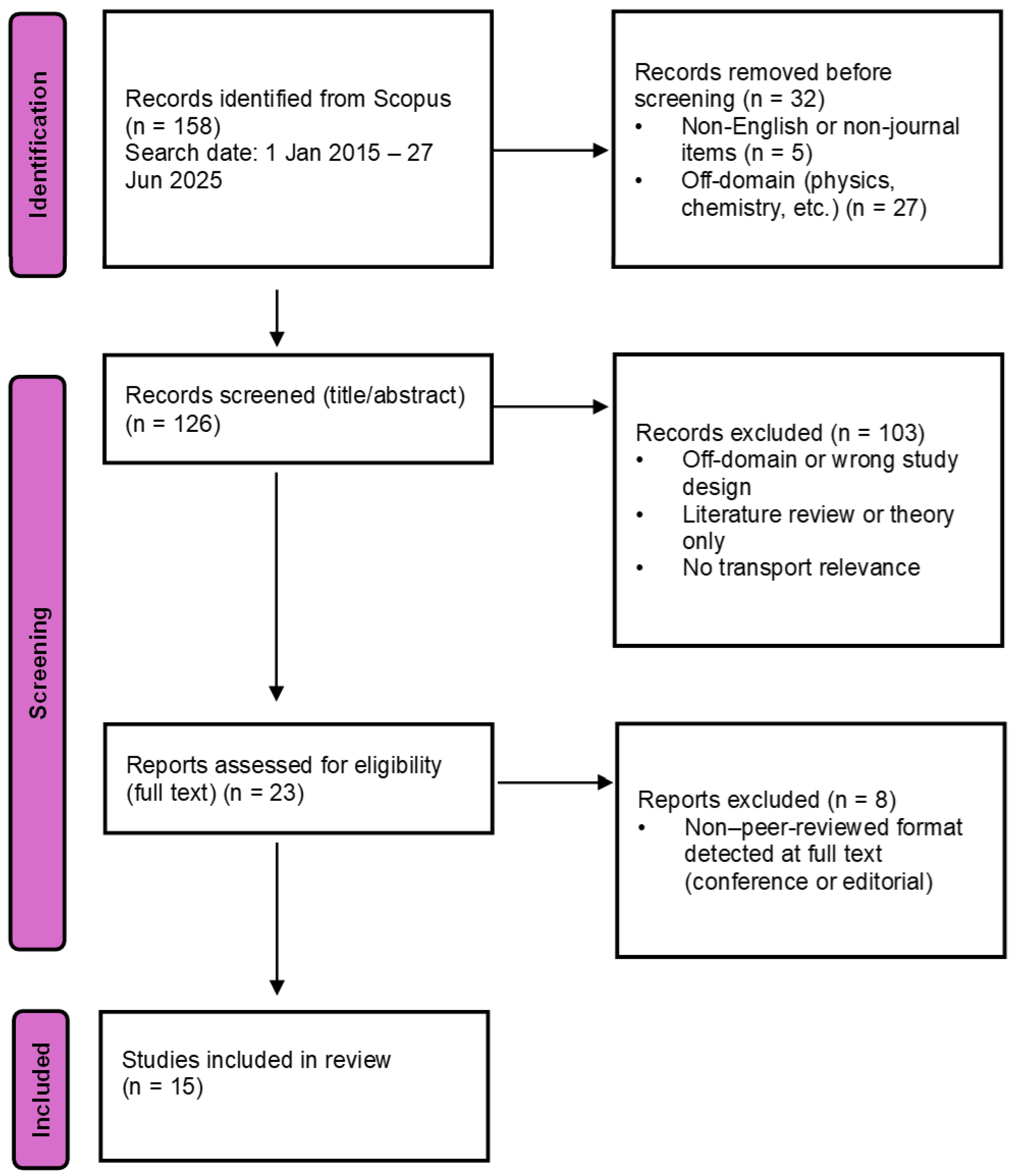

Identification stage Thirty-two records were removed prior to screening because they were non-English or non-journal items (n = 5) or clearly outside the domain (n = 27). No duplicates were found.

Screening stage Titles and abstracts of the remaining 126 records were screened, excluding 103 that were outside the domain, theoretical only, literature reviews, or otherwise irrelevant.

Eligibility stage Full texts of 23 articles were examined in depth; eight were excluded because the publication type, upon inspection, was a conference proceeding or editorial.

A second reviewer selected a random sample of 20% of the title, abstract, and full-text. The interrater agreement yielded Cohen’s k = 0.86, indicating substantial concordance. Fifteen studies met all the criteria and form the basis of this review. The selection process is summarised in

Figure 3.

3.3. Study Characteristics

The fifteen primary studies span publication years 2017 to 2025, with a clear acceleration after 2021. Most research addresses road-transport problems: six papers investigate variants of the vehicle-routing family, two examine factory or robot-scheduling tasks, and two focus on network-design decisions. More specialised contexts include traffic signal optimisation, disaster response routing, plug-in vehicle charging, and urban air mobility trajectory planning, illustrating the growing thematic breadth of the field.

Quantum annealing is the dominant computational approach, appearing in eight studies that deploy commercial D-Wave hardware. Three additional papers employ quantum-inspired digital annealers, while two explore variational circuits executed in noise-free simulators. The remaining studies present conceptual analyses, toolchain developments, or energy footprint measurements. Problem sizes range from toy four-customer routing instances to vehicle-routing-with-time-windows sets containing almost four thousand routes. Where classical baselines are reported, they include tabu search, simulated annealing, mixed-integer programming with the Gurobi solver, and, in one case, an Intel i7 desktop used for energy comparison.

The methodological quality is mixed. Ten studies are judged to have moderate risk of bias because they provide at least one rigorous classical comparator and disclose key hardware parameters, while six are rated high risk due to single-run experiments, the absence of baselines or the heavy reliance on synthetic data. Only three studies release code or datasets and none report end-to-end latency that would be required for real-time deployment. Despite these limitations, the corpus offers a representative cross-section of current quantum and quantum-inspired activity in transport and logistics, serving as a credible basis for the synthesis that follows. For a complete summary, see

Table A1 and

Table A2 in the

Appendix A.

3.4. Data Extraction

A pilot extraction form was implemented in Microsoft Excel. For each study, bibliographic metadata, transport domain, quantum technique, problem size, classical baseline, data provenance, and the availability of code or data were recorded. Quantitative performance outcomes were captured verbatim and free text fields summarised the stated limitations and the barrier category to which each limitation was assigned. The first author carried out the initial extraction; a second author independently re-entered all numerical fields and a 30%sample of the narrative fields. Disagreements were reconciled through discussion and the final concordance rate exceeded 95%. The completed spreadsheet provides the source data for the synthesis presented in

Section 4.

3.5. Quality Appraisal

Methodological quality was evaluated with a bespoke risk-of-bias rubric adapted from critical assessment checklists for computational experiments. The criteria probed the transparency of the problem formulation, the adequacy of classical comparators, statistical rigour, the realism of the dataset, and the disclosure of hardware parameters. Each study was classified as high or moderate risk and the rating was determined by its least robust component. The agreement between the authors for the appraisal stage matched the level attained during screening (k = 0.86; see

Section 3.2).

A formal certainty-of-evidence assessment such as GRADE was not applied, as the included studies are heterogeneous in design and outcome reporting and do not produce quantitative effect measures suitable for that framework.

The risk-of-bias rubric consisted of five components: (i) transparency of the problem formulation, (ii) adequacy of the classical comparator, (iii) statistical rigour and number of runs, (iv) realism of the dataset, and (v) disclosure of hardware parameters. Each component was scored as low, moderate, or high risk based on predefined criteria, and the overall risk rating for each study was determined by its highest-risk component. Disagreements between the two reviewers on risk-of-bias assignments were resolved through discussion.

3.6. Synthesis

Heterogeneity in problem types, hardware platforms, and outcome metrics precluded quantitative meta-analysis. Therefore, a narrative synthesis was conducted: studies were grouped by problem family and quantum approach, and their convergent and divergent findings were mapped onto the barrier taxonomy introduced in

Section 2. The resulting patterns, gaps, and contradictions inform the results (

Section 4) and the discussion (

Section 5). A supplementary search of Web of Science, Springer Nature Link, and IEEE Xplore found no additional peer-reviewed journal articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria, suggesting that reliance on Scopus did not materially limit coverage.

5. Discussion

5.1. Barriers to Practical Implementation of Quantum Computing in Transport and Logistics

Considerable obstacles still separate laboratory demonstrations from operational deployment. At the hardware level, present-generation devices offer fewer than one hundred logical qubits and sparse connectivity, whereas gate fidelities and error-correction overheads curtail circuit depth. An empirical energy audit even reports that modest quantum workloads can draw more power than a conventional desktop processor. Operational barriers compound these technical limits: published case studies overwhelmingly rely on synthetic or down-sampled datasets, rarely report queue latency for cloud-hosted processors, and provide scant evidence of pilot-scale integration. Organisational factors further impede diffusion. Logistics firms struggle to recruit staff who combine quantum expertise with deep domain knowledge, face uncertain capital investment horizons, and navigate a landscape devoid of sector-wide benchmarks or de facto modelling standards [

51,

69]. The cumulative effect of these constraints explains why quantum optimisation remains marginal in daily transport planning despite the clear theoretical promise. These multilayer constraints are visually summarised in the concentric barrier diagram presented in

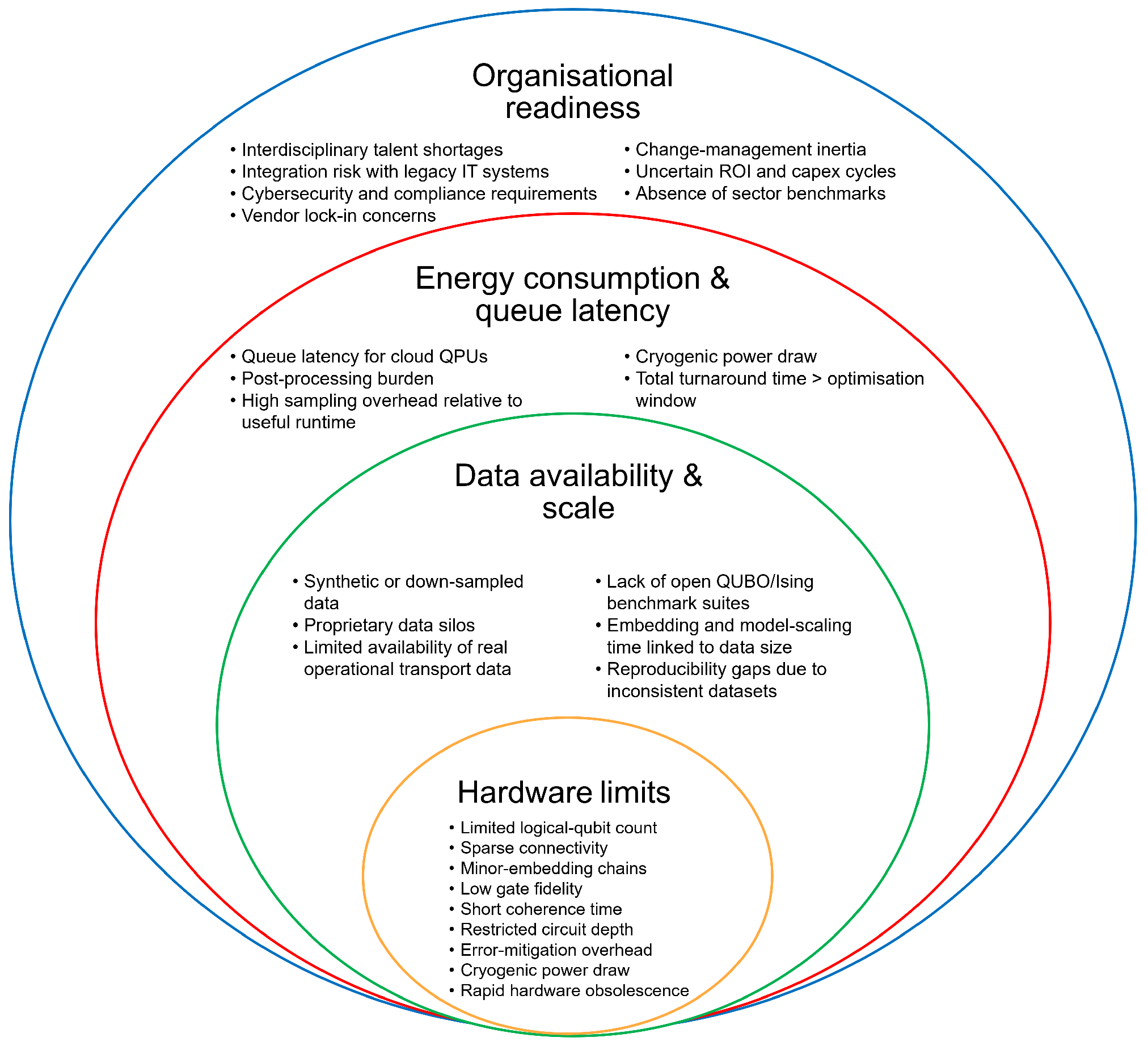

Figure 6. The innermost layer represents hardware limitations that determine the fundamental size and depth of problems that can be executed on current quantum devices. The second layer captures data availability and scale, reflecting the challenges of constructing well-structured QUBO/Ising models from real operational transport data. The third layer represents energy consumption and queue latency, covering execution overheads associated with cloud QPUs, sampling costs and device power requirements. The outermost layer depicts organisational readiness, including workforce capability, IT-system integration, procurement pathways, cybersecurity, and change-management processes. The layering reflects decreasing technical specificity and increasing organisational complexity.

The four barrier categories can be conceptually organised into a concentric structure, where the innermost layer represents the most fundamental technical constraints (hardware limitations), and the outer layers reflect progressively broader system-level requirements. Hardware constraints form the core because they determine the upper bounds of qubit availability, coherence, and circuit depth, which directly limit the size of transport-optimisation instances that can be encoded. The next layer, data availability and scale, concerns the feasibility of constructing well-structured QUBO or Ising representations based on real operational data. The third layer, energy consumption and queue latency, reflects the practical execution costs of using current quantum devices. The outermost layer, organisational readiness, represents institutional capacity, cybersecurity processes, integration with legacy IT, and procurement structures necessary to deploy quantum workflows. These layers reflect a decrease in technical specificity and an increase in organisational complexity, consistent with prior frameworks for the adoption of technology in transport systems [

70].

5.1.1. Hardware Limitations

Current quantum annealing systems provide only modest usable problem sizes once real transport models are mapped to hardware. D-Wave’s latest production platform, Advantage2, offers more than 4400 active qubits in the Zephyr topology with 20-way native connectivity and improved energy scale relative to earlier Pegasus-based Advantage systems [

1,

2,

14]. Real transport models rarely conform to this wiring pattern. To load a model, each logical decision variable is stretched across a chain of connected physical qubits, a process known as minor embedding. Chain overhead consumes qubits and, if chain strengths are not tuned correctly, can degrade solution quality; although the higher degree of Zephyr reduces the average chain length, the effective instance size still falls to only a few thousand binary variables for most transport encodings [

71,

72].

Gate-based quantum processors are more programmable in principle but remain limited in practice by noise. Recent IBM devices exceed one thousand physical superconducting qubits, yet the number of error-corrected logical qubits available for computation is still well below one hundred, placing current platforms firmly in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) regime [

4,

73] IBM Quantum System Two Technical Brief [

74,

75]. Consequently, practical optimisation routines must employ shallow noise-aware ansätze together with error mitigation techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation or read-out correction [

42,

76]. These workarounds improve accuracy but require repeated measurements and parameter re-calibration, which prolong the total run time [

48,

52]. The combined effect of limited variable counts, sparse connectivity, and depth-induced noise explains why every applied demonstration in our corpus addresses problem instances far smaller than those confronted in commercial fleet dispatch or city-scale traffic management [

52,

56,

57].

5.1.2. Data Availability and Scale

Most empirical quantum transport studies published to date have relied on synthetic or heavily downsampled datasets. Examples include very small vehicle routing test beds with only a handful of customers, stylised lattice networks for traffic signal experiments, and reduced reference instances for location-design prototypes [

48,

56,

57]. Even the most ambitious qubit-efficient routing demonstrations validate their encodings on scaled or anonymised data rather than on full production fleets [

52].

Limited access to operational data is a major factor. High-resolution streams from telematics, warehouse management systems, and enterprise resource-planning platforms are commercially sensitive and often bound by confidentiality or privacy regulations, restricting data sharing with academic partners [

51]. Firms also store data in heterogeneous schemas that require extensive cleaning and aggregation before they can be mapped into binary decision variables suitable for quantum encodings [

45]. Unlike conventional operations research, where reference libraries such as the Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem Library (CVRPLIB) [

77], Solomon’s VRPTW set [

59], and the Transportation Network Test Problems [

78], there is no open benchmark suite for quantum-ready transport formulations. The absence of standardised large-scale instances makes it difficult to compare hardware platforms, slows the development of robust encoding strategies, and limits the ability of researchers to reproduce published results across devices. Establishing a shared corpus of transport QUBOs and variational circuit benchmarks is therefore a prerequisite for cumulative progress.

5.1.3. Energy Consumption

Quantitative evidence on the energy cost of quantum optimisation is scarce, yet the limited data available raise caution. The only wall plug audit identified in our search measured the electrical energy required to execute small optimisation kernels on four 5 qbit IBM superconducting processors and compared the results with the same kernels run on an Intel desktop CPU [

17]. The quantum runs consumed orders of magnitude more energy per problem instance than the classical runs. Most of the excess is attributable to the fixed overhead of cryogenic refrigeration, room-temperature control electronics, and the need to repeat circuit executions many times to obtain statistically reliable output distributions [

17,

75,

79]. Engineering surveys of superconducting platforms routinely report continuous kilowatt scale electrical loads to maintain millikelvin temperatures, far larger than the switching energy of the qubits themselves [

75,

79]. Vendor site planning documents for current quantum annealing systems also list multikilowatt system power requirements for cryostats and control stacks [

80,

81], although no peer-reviewed workload-normalised annealer energy study has yet appeared. Apart from the Desdentado audit, none of the applied transport papers in our review reported the energy of the device, the idle time, or the dwell time of the cloud queue [

52,

56,

57]. Until system-level metering protocols are standardised across hardware generations and workloads, claims that quantum optimisation is inherently more energy-efficient than classical high-performance computing should be regarded as provisional [

82].

5.1.4. Organisational Readiness

Evidence from a single multicase study in the corpus [

51] indicates that human capital constraints remain the most immediate barrier to adoption. Firms report difficulty recruiting staff who combine quantum algorithmic competence with deep expertise in routing, scheduling, or inventory management, which lengthens evaluation cycles and inflates the cost of pilot projects, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises without dedicated R&D units [

69,

83]. Sector-wide analyses also highlight ‘talent’ as a foundational enabler for viable quantum innovation clusters.

The risk of integration further discourages experimentation. Quantum optimisers must interoperate with enterprise resource-planning platforms, warehouse management systems, and high-frequency telematics feeds whose data schemas were never designed for unconstrained quadratic binary optimisation inputs or parameterised quantum circuits [

45,

56,

57]. Industry landscape assessments emphasise the need for standardised platforms that facilitate quantum-classical integration, yet such middleware remains immature.

Capital budgeting is complicated by rapid hardware evolution and uneven investment signals: large public programmes and private rounds continue to enter the field, but technology road maps and cost structures are still in flux, making payback calculations difficult for transport operators with tight margins [

83].

Finally, the transport sector lacks shared norms for model formulation, performance reporting, and cyber security compliance in quantum workflows. Global policy attention to the readiness for the ‘Q Day’ shows that data security standards and interoperability frameworks are moving up national and industry agendas, yet sector-specific guidance for transport and logistics has not emerged [

83,

84,

85].

In combination, talent scarcity, integration uncertainty, capital risk, and missing standards constitute a substantial readiness gap that must be closed before quantum optimisation can progress from laboratory pilots to routine operational use.

5.2. Emerging Patterns

Three regularities emerge from the evidence base. First, most empirical studies rely on quantum annealing hardware or Ising model abstractions. This dominance reflects the ease with which discrete transport decisions, such as vehicle-to-customer assignments, facility openings, and signal phasing, can be expressed in a quadratic unconstrained binary optimisation framework. Second, quantum-inspired digital annealers increasingly serve as an intermediate industrial solution: they inherit the modelling convenience of Ising formulations yet circumvent qubit scarcity by running on conventional complementary-metal–oxide–semiconductor chips, thereby addressing problems with tens of thousands of variables at subsecond speed. The robot lab scheduling benchmark (Study 2 [

54]) is the only study in the corpus that achieves near-real-time performance at that scale. Finally, algorithmic progress is as much a matter of encoding engineering as of hardware advance. Logarithmic qubit encodings and other compression schemes enable variational circuits, even on noisy intermediate-scale quantum processors, to represent fleet-routing instances of realistic scale without breaching depth or connectivity limits.

5.3. Inconsistencies and Contradictions

The corpus exhibits several notable tensions. An energy footprint study reports that the execution of small optimisation workloads on current-generation quantum devices can draw more electrical power than an equivalently sized classical run (study 5 [

17]), while a separate investigation of noise-enhanced annealing (study 9 [

58]) for plug-in vehicle charging infers cost savings from reduced charging time. The divergence arises partly from different system boundaries: the former measures wall plug energy, including cryogenic cooling and repeated circuit sampling, while the latter models algorithmic runtime only and excludes hardware overhead. Until energy accounting is standardised at the system level, claims that quantum optimisation is intrinsically “greener” than classical computation remain unsubstantiated.

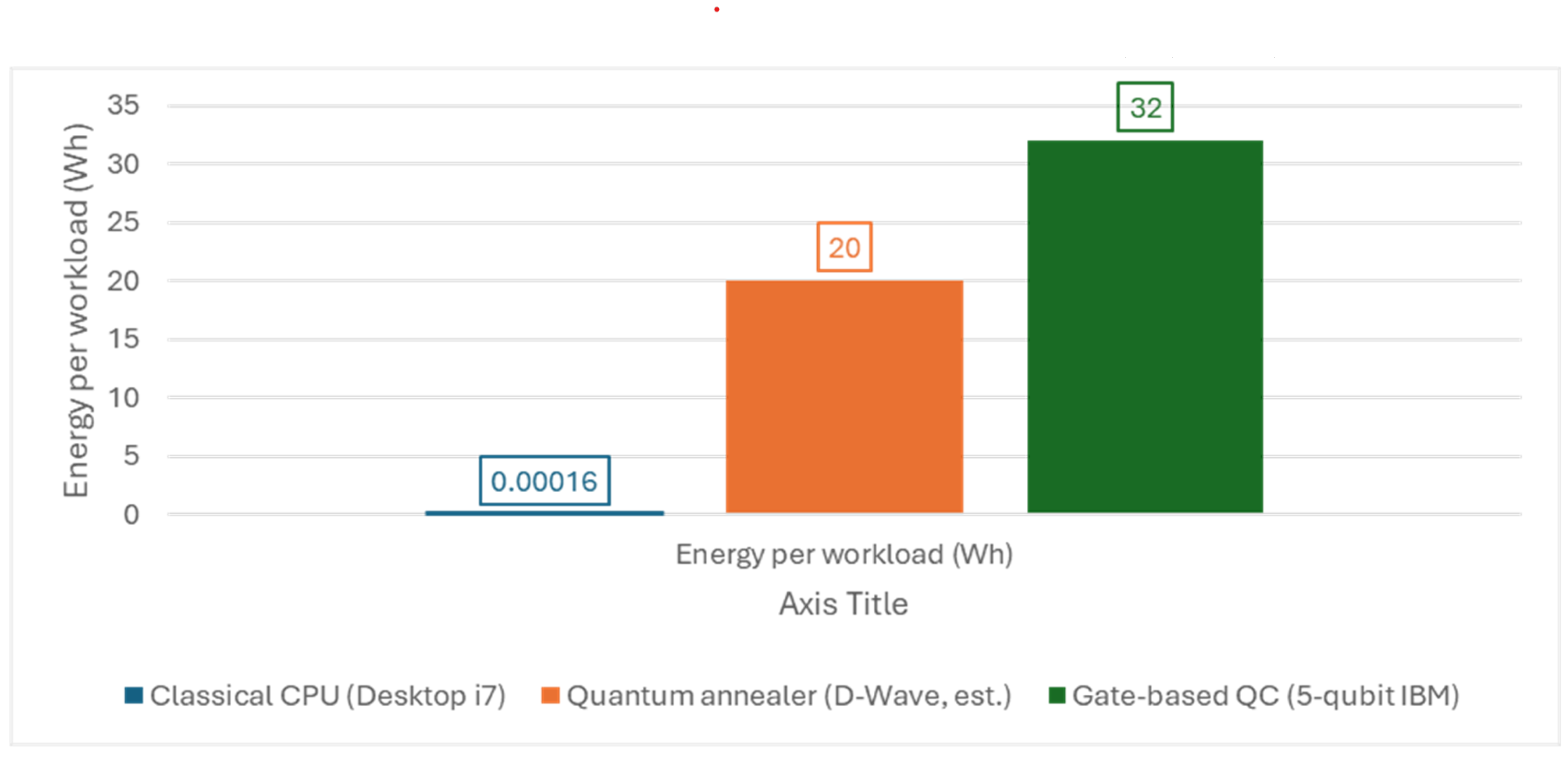

Figure 7 compares the energy required to execute a single optimisation workload on three computing platforms that feature prominently in the recent literature. The classical reference system, an Intel i7-10700 workstation, drew just 0.00016 Wh per run, a value measured at the wall plug by Desdentado et al. [

17]. The same workload on a five-qubit gate-based device from IBM consumed 32 Wh once cryogenic cooling and repeated circuit sampling were included, again according to Desdentado et al. [

17] (Tables 14 and 15). The centre bar represents a D-Wave quantum annealer and is set at 20 Wh per run, an upper-bound estimate obtained by multiplying the typical system power reported by the vendor (about 20 kW) by the three-to-four-second job times documented in recent annealing studies such as Ding et al. [

56] and Marchesin et al. [

57]. Because an annealer operates continuously at cryogenic temperature, most of its electrical load is incurred even when the processor is idle; consequently, the marginal energy per job can be expected to lie between the classical and gate-based extremes shown here. Taken together, these measurements indicate that, at the modest problem sizes addressed so far, quantum hardware remains several orders of magnitude more energy-intensive than commodity classical processors, a finding that calls for system-wide efficiency improvements before quantum optimisation can plausibly claim a sustainability advantage.

A second inconsistency concerns performance claims. Several articles define “speed-up” solely in terms of quantum processing unit sampling time, omitting classical pre- and post-processing as well as queue latency, while others report end-to-end solver runtime.

A second inconsistency concerns performance claims. Several articles define “speed-up” solely in terms of the sampling time of the quantum processing unit and omit classical pre- and post-processing, as well as queue latency; other articles report an end-to-end solver runtime that includes those stages. This distinction is especially consequential for shared cloud gate-based services such as IBM Quantum, where user jobs may wait orders of magnitude longer in a queue than the underlying circuit execution [

48].

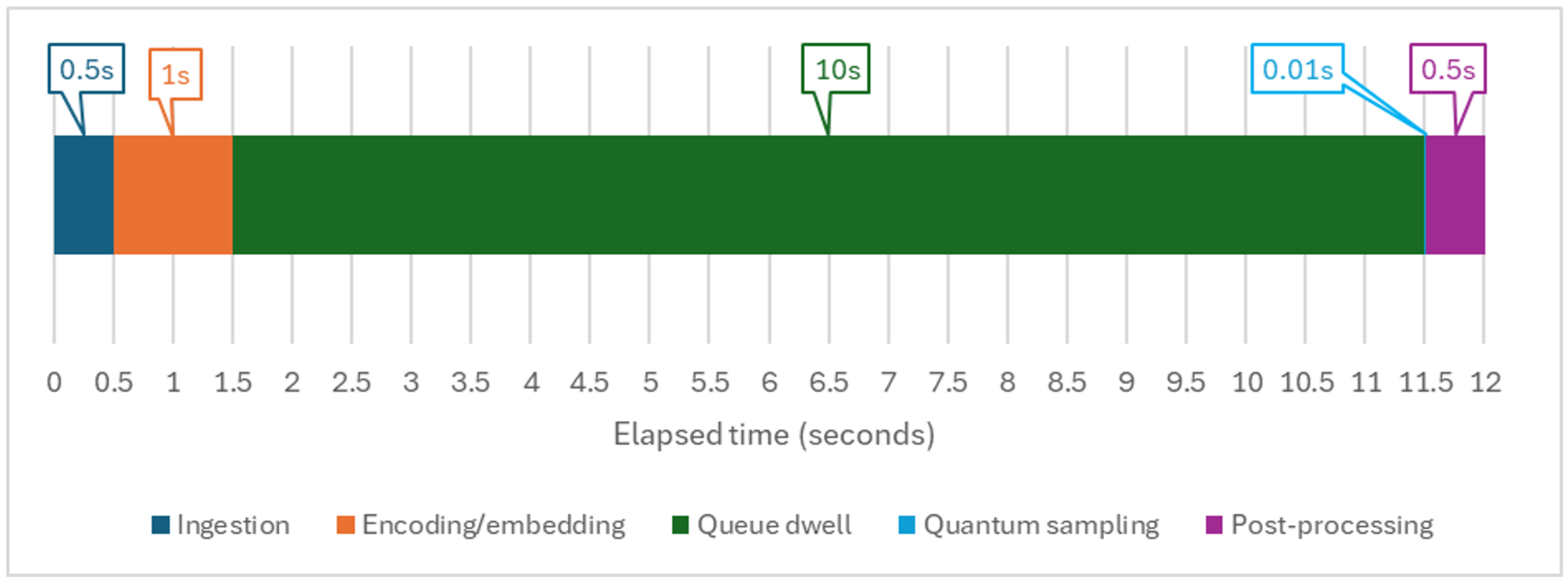

Figure 8 illustrates the full latency path between the arrival of a transport optimisation request and the return of an actionable decision. The segment lengths in

Figure 8 are illustrative, not prescriptive: 0.5 s for ingestion and 1 s for embedding reflect median values reported for high-throughput telemetry pipelines in logistics platforms; the 10 s queue dwell is a conservative figure drawn from typical IBM Quantum Runtime wait times in public cloud experiments; the 0.01 s quantum sampling bar matches the order of magnitude measured on both D Wave Advantage annealers and shallow gate-based circuits; and the final 0.5 s post-processing slot corresponds to route decoding routines in our Incoming telemetry or order records first enter an ingestion layer that cleans, aggregates, and time aligns the data. The cleansed stream is then converted into a representation suitable for quantum hardware, either a quadratic unconstrained binary optimisation matrix for an annealer or a parameterised gate circuit for a gate-based processor; this encoding step also performs minor embedding for annealers or qubit mapping for gate devices. The encoded job then joins a cloud-scheduler queue, where it may wait several seconds, and in busy public clouds often much longer than any other stage, before the quantum processor becomes available (IBM Quantum Runtime documentation: Estimate job run time and queue wait time,

https://quantum.cloud.ibm.com/docs/en/guides/estimate-job-run-time accessed 1 July 2025). Once dequeued, the hardware executes the quantum sampling phase, which typically lasts only milliseconds on an annealer and a few hundred microseconds on a shallow variational circuit. The resulting bit strings or expectation values then undergo classical post-processing to decode vehicle routes, robot schedules, or signal plans. The decoded solution is finally relayed to the host decision service such as a fleet dispatch application programming interface or a traffic signal controller and is applied in the operational system. The stacked-bar timeline underscores that queue delay and classical workflow overhead dominate total turnaround, while the quantum step itself occupies a very small fraction of end-to-end latency.

Studies of practical deployments highlight that the nominal speed of the quantum step is often dwarfed by the combined duration of encoding, queue latency, and post-processing. Ding et al. [

56] report minor embedding runtimes that can exceed the annealing time by a factor of two, while Marchesin et al. [

57] note that queuing delays in shared cloud environments introduce variability that masks hardware level speed-ups. The absence of a shared benchmarking protocol hampers direct comparison and risks overstating quantum advantage. When performance is reported only for the quantum processing unit sampling step and excludes data embedding, post-processing, or cloud queue latency, the resulting figures are not comparable with studies that publish end-to-end runtimes; they also inflate the apparent quantum advantage.

For practice, this finding implies two concrete needs: standardised reporting conventions and benchmarking. Until these non-quantum components are streamlined and measured alongside sampling time, claims of real-time performance will remain speculative.

Other contradictions were found around the data translation overhead. Two annealing studies on facility location (study 6 [

56]) and transport network design (study 11 [

10]) report that minor embedding, coefficient scaling, and solution decoding together consume more elapsed time than the quantum sampling phase itself, in some cases by a factor of two. This result indicates that the main bottleneck in current workflows resides in the interface layer rather than in the quantum processor, and calls into question speed-up claims that omit preprocessing costs. A rigorous assessment of quantum advantage therefore requires end-to-end latency accounting and the development of standardised automated embedding pipelines. At the same time, the predominance of data-translation overhead implies that quantum acceleration cannot be realised by hardware upgrades alone; performance depends just as critically on the software interface that maps transport problems into quantum-ready formats. For practitioners, this observation has several operational consequences, including unrealistic expectations about end-to-end decision latency and misguided toolchain investment.

5.4. Key Unresolved Gaps

Four critical gaps persist in the current research landscape (see

Table 6). Firstly, empirical validation remains limited, as no reviewed study reports on a full-scale quantum optimisation deployment within a functioning traffic management system, logistics hub, or operational fleet-dispatch platform. Consequently, the practical applicability and external validity of quantum solutions have not been rigorously tested against real-world operational constraints. Addressing this shortcoming would require researchers to collaborate directly with transport operators and logistics providers to establish realistic pilot implementations, generating robust performance data under authentic operational conditions.

Secondly, the studies reviewed predominantly rely on artificially generated or simplified datasets, limiting their relevance to practical scenarios. The absence of publicly available, community-curated benchmark datasets tailored explicitly for quantum optimisation in transportation and logistics further exacerbates this challenge, hindering reproducibility and comparative assessments across different hardware generations and algorithmic approaches. Developing a standardised Quantum Transport Benchmark Suite (QTBS), encompassing representative instances of vehicle routing, network design, traffic signal optimisation, and other canonical problems, would substantially enhance transparency, enable systematic replication, and accelerate the advancement of practical solutions.

Third, statistical robustness and experimental rigour remain unrecognised in many studies. The majority report performance metrics derived from single-run or minimal-repeat experiments, which fail to capture the inherent variability and stochastic ability of quantum hardware, especially on noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices. This practice inflates perceived performance and underestimates variance, potentially misleading practitioners with respect to the reliability of results. Implementing rigorous statistical protocols, such as multi-instance testing with a sufficiently large number of independent runs (e.g., 30 or more) and consistently reporting variance or confidence intervals would significantly improve the robustness and credibility of the experimental outcomes.

Lastly, comprehensive reporting of operational metrics, particularly energy consumption and queue latency, is notably absent. Given their critical role in determining the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of quantum computing in real-world scenarios, omitting these factors undermines thorough cost–benefit evaluations. To remedy this, future studies should systematically include full system-level audits of both energy usage and queue latency alongside traditional performance metrics, thus providing clearer insights into the practical implications of quantum optimisation deployments.

In summary, addressing the four gaps of real-world pilot deployments, standardised benchmarking, robust statistical design, and comprehensive energy and latency accounting is essential to bridge the current divide between laboratory demonstrations and practical quantum optimisation applications in transport and logistics.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This systematic review has several limitations. It exclusively searched the Scopus database, potentially excluding relevant grey literature, conference proceedings, and articles indexed solely in other databases. Although supplementary searches of Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and Springer Nature Link did not yield additional eligible studies, the possibility of missed literature remains. Moreover, given the rapid pace of quantum computing advancements, the findings and identified barriers reflect a snapshot of a rapidly evolving field, necessitating periodic updates to maintain relevance.

Future research should prioritise controlled field trials in collaboration with municipal traffic management centres, logistics providers, and fleet operators to assess quantum-optimised solutions under realistic operational conditions. Such trials would directly test robustness against real-world variability, stochastic demand, and potential hardware downtimes, generating credible data on the operational feasibility and reliability of quantum technology.

Comparative cross-layer studies examining the energy efficiency of quantum hardware, high-performance classical computers, and quantum-inspired digital annealers on identical optimisation workloads should also be conducted. Rigorous and transparent energy audits, coupled with standardised end-to-end latency measurements, would enable meaningful cost–benefit analyses and sustainability assessments, addressing critical gaps identified in this review.

Moreover, algorithmic advances should continue to focus on hybrid methods with zero error. Techniques integrating quantum annealing or variational circuit sampling with classical local-search heuristics may improve overall solution quality and resilience against quantum hardware noise. Research into multi-objective optimisation frameworks explicitly incorporating not only cost and operational efficiency but also environmental emissions and equitable service distribution could align future quantum optimisation research with emerging transport policy priorities.

Finally, developing interactive human-in-the-loop quantum optimisation interfaces is recommended to leverage expert domain knowledge effectively. Such interfaces could enable transport and logistics professionals to iteratively refine constraints and solution preferences during the quantum optimisation process, increasing practical usability and acceptance in real-world decision-making environments.

In summary, these future research directions collectively represent a structured path toward operationally viable, transparently benchmarked, and methodologically rigorous quantum optimisation tools tailored explicitly for transport and logistics applications.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review critically synthesised 15 empirical studies published between 2015 and 2025, examining the application of quantum and quantum-inspired computational methods to optimisation problems in the transport and logistics domain. The findings indicate that quantum annealers can approach classical heuristic performance on small, constrained instances of routing, network design, and traffic-control problems in controlled conditions. Quantum-inspired digital annealers demonstrate improved scalability and have been applied to larger benchmark instances, although widespread industrial deployment in transport remains limited. Additionally, advances in qubit-efficient encoding techniques indicate that NISQ processors may, in the future, be able to address moderately sized routing scenarios in simulations, although significant scaling challenges remain.

Despite these promising developments, significant methodological and empirical gaps persist. Many studies rely heavily on synthetic or simplified datasets, employ single-run or best-case experimental designs, and use performance metrics specific to particular hardware configurations, complicating any robust generalisation of results. Validations under live operational transport conditions remain rare. Most studies rely on synthetic or simplified datasets and seldom report energy-consumption or quantum-processor queue-latency measurements, both of which are critical for evaluating practical economic viability.

Addressing these critical gaps requires methodological improvements, including establishing open-access benchmark datasets, implementing statistically robust multi-run experimental protocols, and performing transparent, comprehensive energy and latency audits. Industry-academia collaborations will be crucial to obtain realistic datasets, define sector-specific benchmarks, and rigorously test quantum methods under authentic operational conditions.

Overall, this review identifies quantum optimisation as a nascent approach with potential for addressing complex optimisation tasks in transport and logistics, contingent on future progress in hardware scalability, energy efficiency, and methodological robustness. Realising this potential will require targeted efforts to improve methodological transparency and achieve practical validation through real-world deployment.