Pedal Power: Operational Models, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Bike Lending in North America

Highlights

- Bike lending programs lower cost and access barriers to encourage cycling adoption.

- Programs personalize experiences via bike fittings, gears, and safety training.

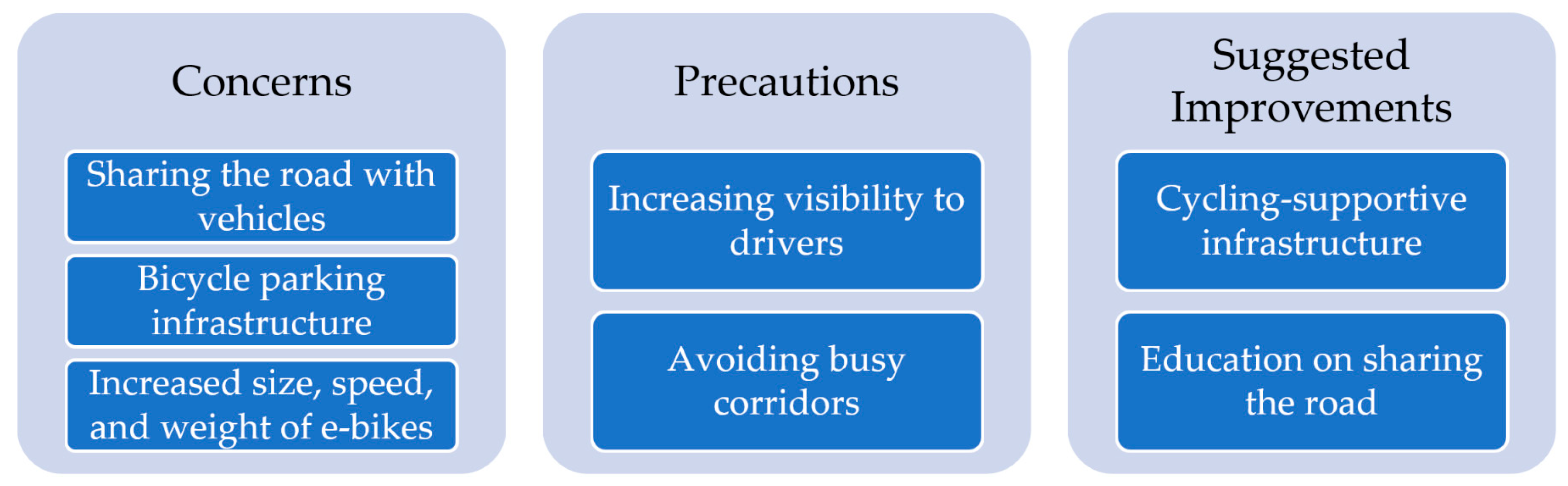

- Bike lending experts and users recommend more cycling infrastructure to increase safety and use.

- The findings imply that sustained investment in bike lending programs and supportive cycling infrastructure can enhance equitable access, safety, and long-term adoption of cycling as a sustainable transportation mode.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

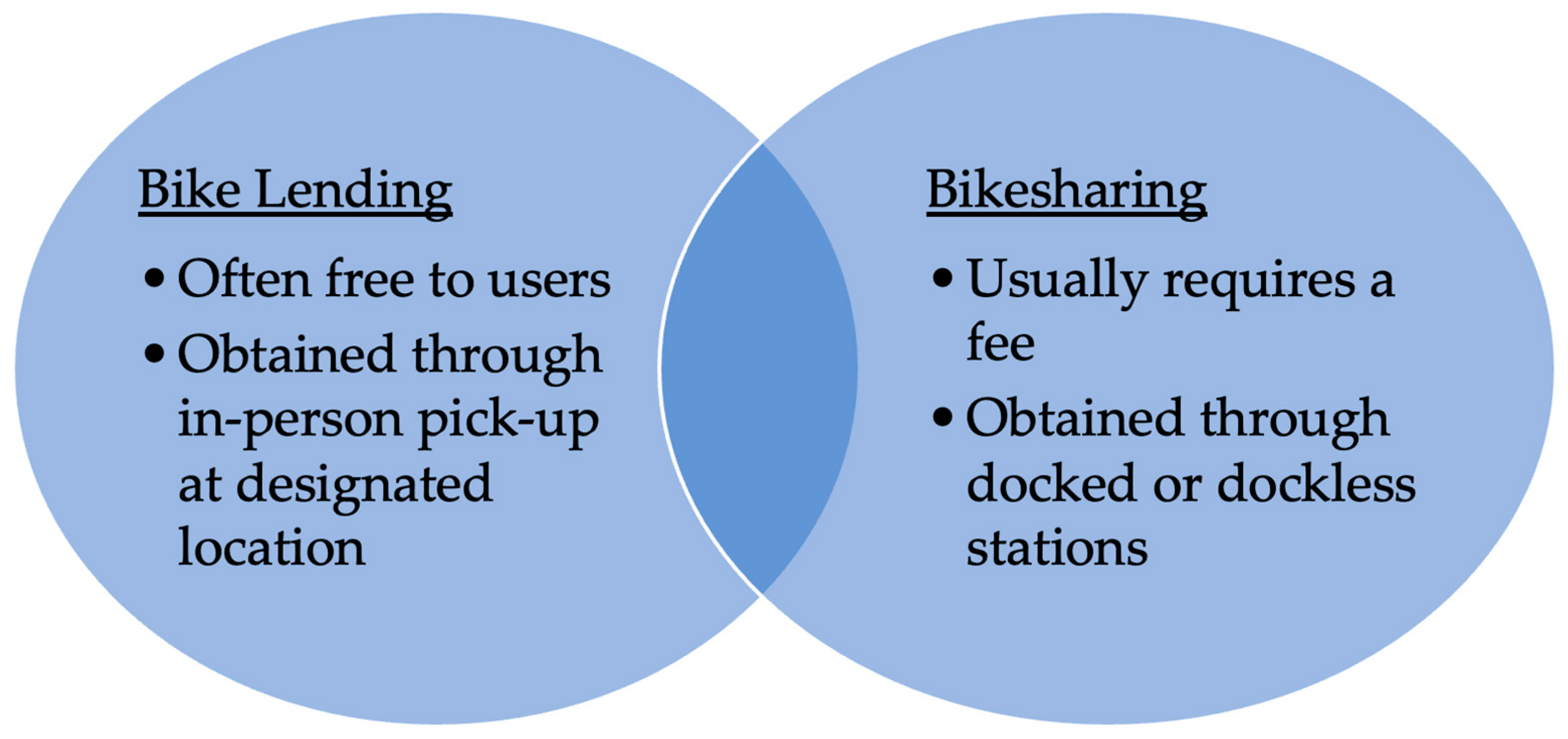

2.1. Bike Lending Business Models

2.2. Role and Impact of Bike Lending Programs

2.3. Barriers to Bike Lending and Adoption of Cycling

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Identification and Characterization of Bike Lending Programs

- General information (i.e., location, type of organization, year of inception);

- Bike types offered (i.e., e-bikes, mountains bikes, children’s bikes, tricycles, etc.);

- Accessories offered (i.e., helmet, basket, bike lock, etc.);

- Populations served (i.e., general, youth, low income, etc.);

- Lending arrangements (i.e., requirement of user agreement/waiver, library, card, photo ID, deposit, etc.);

- Safety training (i.e., education provided on helmet use, hand signals, road signage, etc.);

- Other services/incentives offered (i.e., bike purchase assistance, bike purchase discount);

- Additional information (i.e., website link, contact information).

3.2. Expert Interviews

3.3. Survey of Operators

3.4. Focus Groups

4. Results

4.1. Bike Lending Growth, Program Goals, and Funding

4.1.1. History of Bike Lending

4.1.2. Distribution of Bike Lending Programs

- Lane Community College,

- Roanoke College,

- Rollins College,

- Montclair State University,

- University of California, Berkeley,

- University of Massachusetts Amherst, and

- University of Oregon.

4.1.3. Bike Lending Objectives and Populations Served

- Encouraging the exploratory use of bikes to inform future purchase decisions, especially for e-bikes;

- Promoting awareness and education about cycling as a clean transportation mode;

- Providing bicycles for transportation and to support physical activity;

- Bringing a clean mobility option to an underserved community;

- Reducing financial barriers for children or low-income families to access bikes; and

- Building a community of cyclists that may influence infrastructure changes.

4.1.4. Funding

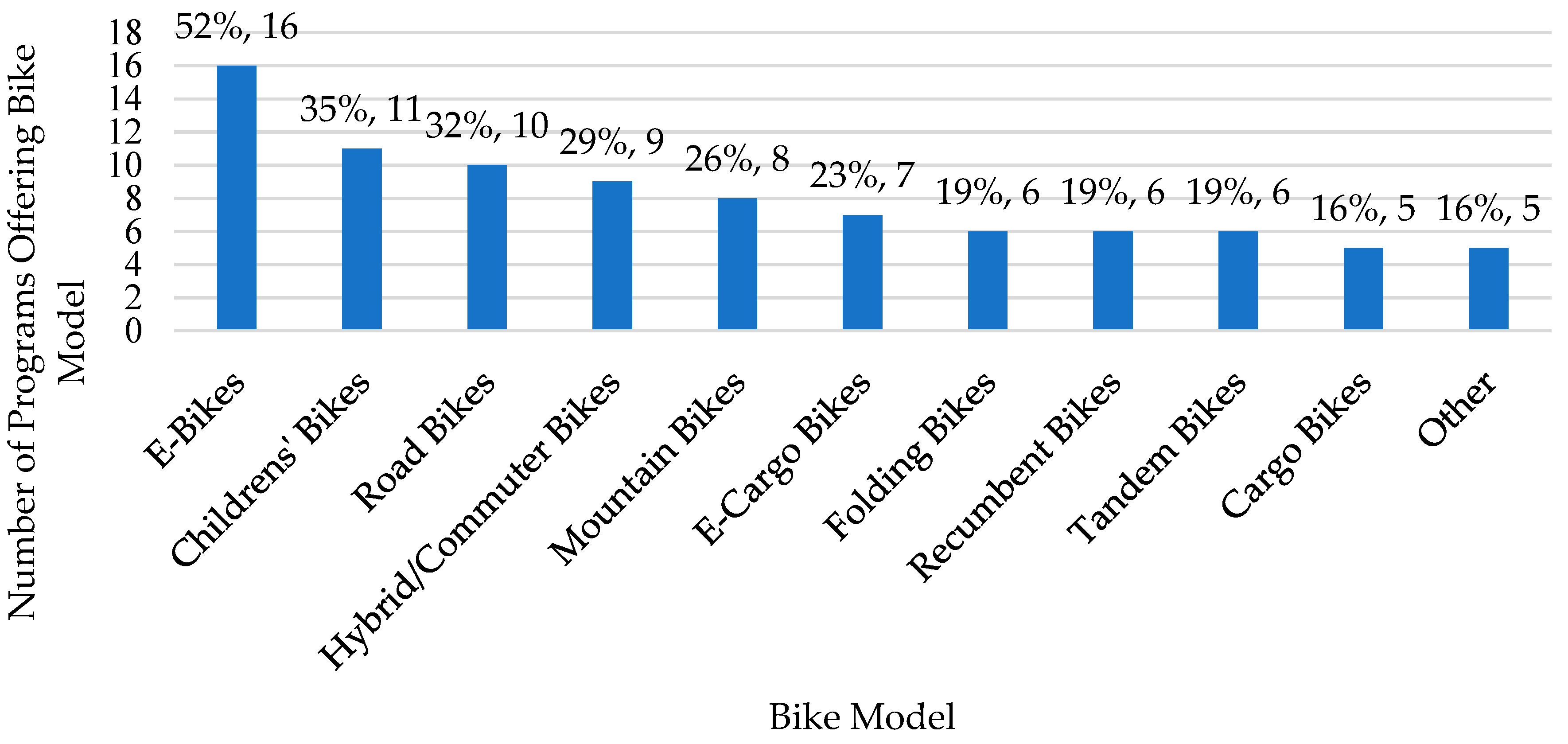

4.1.5. Bike Lending Fleets and Bike Models

4.2. Bike Lending Operations

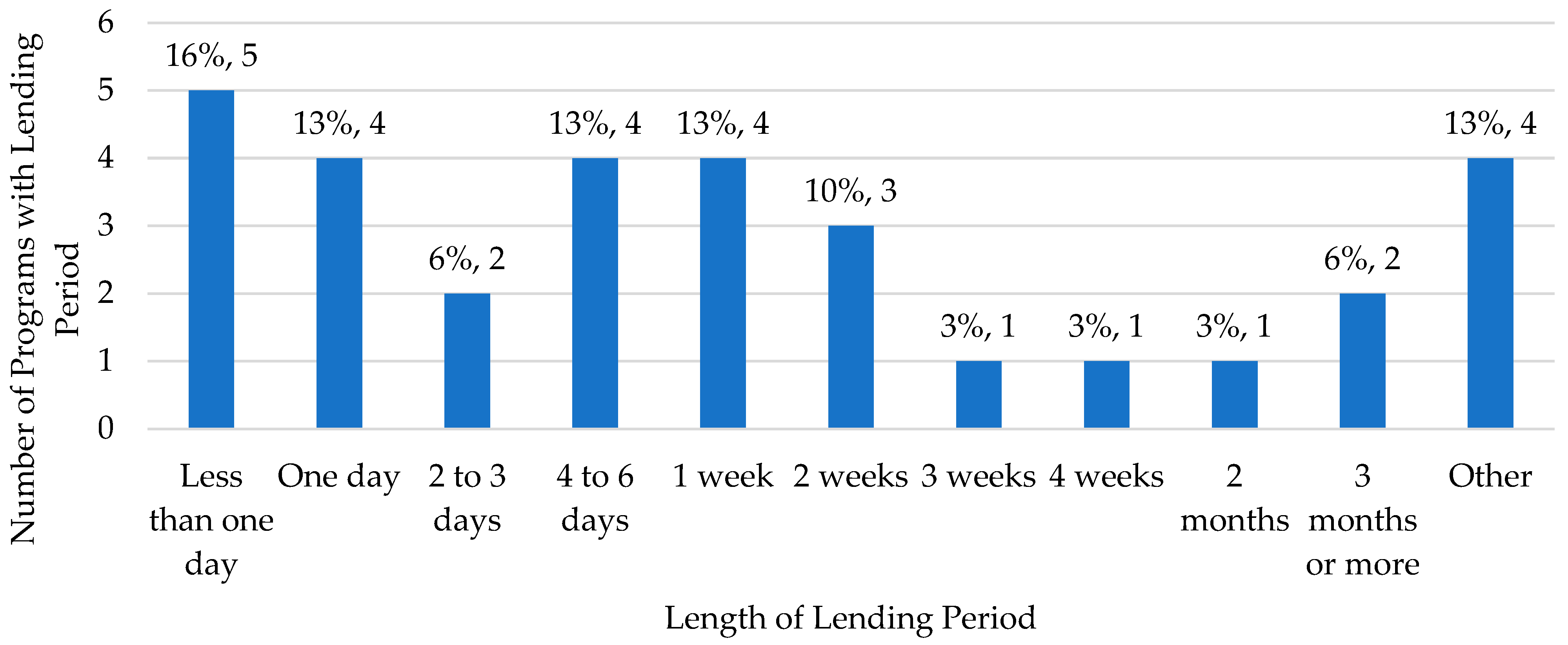

4.2.1. Bike Lending Program Operations and Participation Onboarding Process

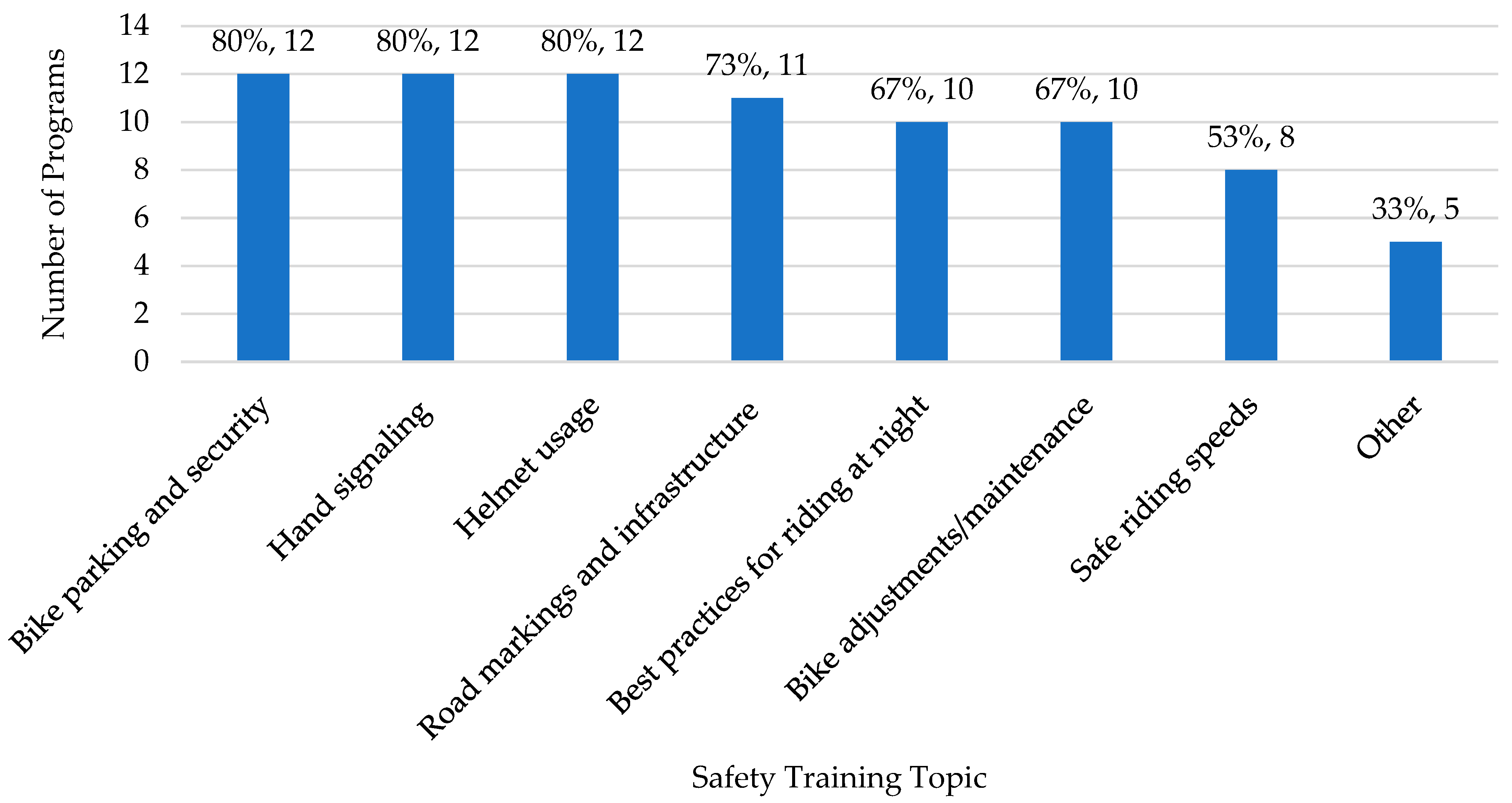

4.2.2. Safety Training

4.2.3. Program Insurance

- Accept liability risks without insurance due to high insurance costs;

- Have insurance through a broader policy that may cover other programs or a broader entity (i.e., city recreation department that supports various activities); or

- Hold their own insurance policy.

4.2.4. Support and Resources for Bike Lending Programs

4.3. Bike Lending Experience and User Impacts

4.3.1. Bike Lending Participation and Bike Use

4.3.2. Safety Among Participants

4.3.3. Bike Safety and Infrastructure

4.3.4. Impacts of Bike Lending

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings on Bike Lending Operations

5.2. Safety and Infrastructure Insights

5.3. Policy Recommendations

5.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U.S. | United States |

References

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A.; Martin, E. Public Bikesharing in North America: Early Operator Understanding and Emerging Trends. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2389, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JA3163_202106; Taxonomy of On-Demand and Shared Mobility: Ground, Aviation, and Marine. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/ja3163_202106/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Assuncao-Denos, M.-E. The Ups and Downs of Bike-Sharing Systems in North America: Understanding the Successes and Struggles; McGill University eScholarship: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/papers/8s45q909x (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Bliss, L. E-Bike Lending Libraries Aim to Boost Adoption. Bloomberg. 15 October 2021. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-15/e-bike-lending-libraries-aim-to-boost-adoption (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- MacArthur, J.; Miller, J.; Swain, I. E-Bike Lending Libraries: Trends and Practices in the United States; Portland State University, Transportation Research and Education Center: Portland, OR, USA, 2025. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/83378 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Berger, B.; Reback, M.; Palmatier, S.M. Addressing the Barriers to Bicycling: A Bike Access Program in Lewiston and Auburn, ME. Community Engaged Res. Rep. 2018, 46, 4–39. Available online: https://scarab.bates.edu/community_engaged_research/46 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- McNeil, N.; Broach, J.; Dill, J. Breaking Barriers to Bike Share: Lessons on Bike Share Equity; Institute of Transportation Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 31–35. Available online: https://ppms.trec.pdx.edu/media/project_files/ITE_Jounal_February_2018_Breaking_Barriers_to_Bike_Share_Lessons_on_Bike_Share_Equity.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Janzer, C. Bike Libraries Are Boosting Access to Bike Across the U.S. Next City. 24 October 2022. Available online: https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/bike-libraries-are-increasing-access-to-bikes-across-america (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- The Bike Center. Commuter Bike Loan Program. Available online: https://thebikecenter.com/commuter-bike-loan-program/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Fitch, D.; Gao, Z.; Noble, L.; Mac, T. Examining the Effects of a Bike and E-Bike Lending Program on Commuting Behavior; Mineta Transportation Institute Publications: San Jose, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskell, S.; Xu, W.; Rissel, C. Encouraging community cycling and physical activity: A user survey of a community bicycle loan scheme. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2010, 21, 2–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, E. The Social Implications of Bicycle Infrastructure: What it Means to Bike in America’s Best Cycling Cities; Macalester College Digital Commons: St Paul, MN, USA, 2014; Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=geography_honors (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Safer Cycling Through Improved Infrastructure. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 2089–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The League of American Bicyclists. National: Biking & Walking Road Safety; The League of American Bicyclists: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://data.bikeleague.org/data/national-bicyclist-pedestrian-road-safety/#number-of-annual-bicyclist-fatalities (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Canadian Automobile Association. Cycling by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.caa.ca/driving-safely/cycling/bike-statistics/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Davis, W. How to Build a Bike Lane in America. The Verge. 9 December 2023. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/23992114/bike-lane-us-infrastructure-milwaukee-dallas-woodlands (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- National Association of City Transportation Officials. High-Quality Bike Facilities Increase Ridership and Make Biking Safer; National Association of City Transportation Officials: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://nacto.org/latest/high-quality-bike-facilities-increase-ridership-make-biking-safer/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Fowler, S.L.; Berrigan, D.; Pollack, K.M. Perceived barriers to bicycling in an urban U.S. environment. J. Transp. Health 2017, 6, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, J.; Harpool, M.; Schepke, D.; Cherry, C. A North American Survey of Electric Bicycle Owners; Transportation Research and Education Center: Portland, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Morena, L.F.; Nosal, T. Weather or Not to Cycle: Temporal Trends and Impact of Weather on Cycling in an Urban Environment. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2247, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle Tonoian, J. Power to the Pedal: Assessing Barriers to Adoption of Closed-Access Bike Share in Low-Income Communities. Bachelor’s Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurford, M. Bike Libraries Are Growing in Popularity, and That’s a Good Thing! Bicycling. 31 October 2022. Available online: https://www.bicycling.com/culture/a41802584/bike-libraries-growing-in-popularity/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- PeopleForBikes. Statement on Electrically Powered Devices. PeopleForBikes. 2021. Available online: https://peopleforbikes.cdn.prismic.io/peopleforbikes/22cafb3e-7284-456d-9a7d-5dfa4208d935_PeopleForBikes+Statement+on+Electrically+Powered+Devices+032621.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

| Bike Lending Programs Operating Under Non-Profit Organizations | Bike Lending Programs Operated by Public Entities | Bike Lending Programs Operated by Non-Profit Transportation Organizations | Other Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| Benefits of Bike Lending | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health benefits | 19 | 63% |

| Mental health benefits | 15 | 50% |

| Access to essential services | 10 | 33% |

| Economic opportunity | 9 | 30% |

| Social equity impacts | 9 | 30% |

| Environmental benefits | 8 | 27% |

| Reduced trip costs | 7 | 23% |

| Reduced trip time | 3 | 10% |

| Other | 3 | 10% |

| Offers E-Bikes or E-Cargo Bikes | Does Not Offer E-Bikes or E-Cargo Bikes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requires Safety Training | 7 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 7 |

| Does Not Require Safety Training | 6 (19%) | 10 (32%) | 16 |

| Does Not Require Safety Training, But Offers Optional Safety Training/Programming | 5 (16%) | 3 (10%) | 8 |

| Total | 18 | 13 | 31 |

| Resources Needed to Support Bike Lending | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Bike friendly infrastructure | 25 | 83% |

| Local funding | 24 | 80% |

| Public sector partnerships | 14 | 47% |

| Private sector partnerships | 13 | 43% |

| Regional funding | 12 | 40% |

| State funding | 12 | 40% |

| Federal funding | 9 | 30% |

| Other | 6 | 20% |

| Bike Purchase Status | Count (n = 10) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, and participants can purchase their own bike from us or a partnering bike shop. | 4 | 40% |

| Yes, however, we do not have any bikes for sale. | 2 | 20% |

| No, most participants of this program use but then cannot afford to purchase their own bike. | 1 | 10% |

| No, most participants do not have a desire to purchase a bike. | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 2 | 20% |

| I am not sure | 1 | 10% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaheen, S.; Wolfe, B.; Cohen, A. Pedal Power: Operational Models, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Bike Lending in North America. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060185

Shaheen S, Wolfe B, Cohen A. Pedal Power: Operational Models, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Bike Lending in North America. Smart Cities. 2025; 8(6):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060185

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaheen, Susan, Brooke Wolfe, and Adam Cohen. 2025. "Pedal Power: Operational Models, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Bike Lending in North America" Smart Cities 8, no. 6: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060185

APA StyleShaheen, S., Wolfe, B., & Cohen, A. (2025). Pedal Power: Operational Models, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Bike Lending in North America. Smart Cities, 8(6), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060185