Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The integration of generative AI with blockchain improves contract scalability and enhances data security.

- The proposed framework outperforms both traditional and other AI-optimized smart contract methods.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Enables the development of more efficient, secure, and scalable smart contract-based services in smart cities.

- Supports energy-efficient and low-overhead deployment of decentralized applications using AI-enhanced blockchain frameworks.

Abstract

Smart cities use advanced infrastructure and technology to improve the quality of life for their citizens. Collaborative services in smart cities are making the smart city ecosystem more reliable. These services are required to enhance the operation of interoperable systems, such as smart transportation services that share their data with smart safety services to execute emergency response, surveillance, and criminal prevention measures. However, an important issue in this ecosystem is data security, which involves the protection of sensitive data exchange during the interoperability of heterogeneous smart services. Researchers have addressed these issues through blockchain integration and the implementation of smart contracts, where collaborative applications can enhance both the efficiency and security of the smart city ecosystem. Despite these facts, complexity is an issue in smart contracts since complex coding associated with their deployment might influence the performance and scalability of collaborative applications in interconnected systems. These challenges underscore the need to optimize smart contract code to ensure efficient and scalable solutions in the smart city ecosystem. In this article, we propose a new framework that integrates generative AI with blockchain in order to eliminate the limitations of smart contracts. We make use of models such as GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT4, which natively can write and optimize code in an efficient manner and support multiple programming languages, including Python 3.12.x and Solidity. To validate our proposed framework, we integrate these models with already existing frameworks for collaborative smart services to optimize smart contract code, reducing resource-intensive processes while maintaining security and efficiency. Our findings demonstrate that GPT-4-based optimized smart contracts outperform other optimized and non-optimized approaches. This integration reduces smart contract execution overhead, enhances security, and improves scalability, paving the way for a more robust and efficient smart contract ecosystem in smart city applications.

1. Introduction

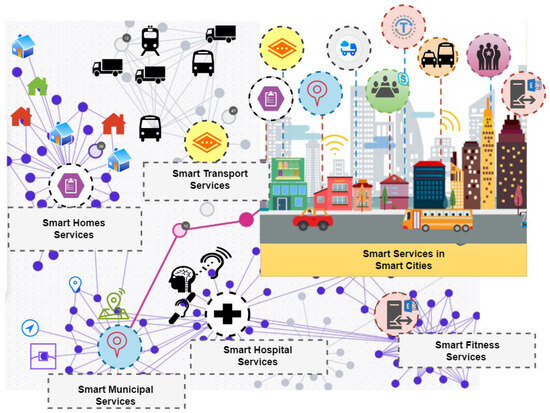

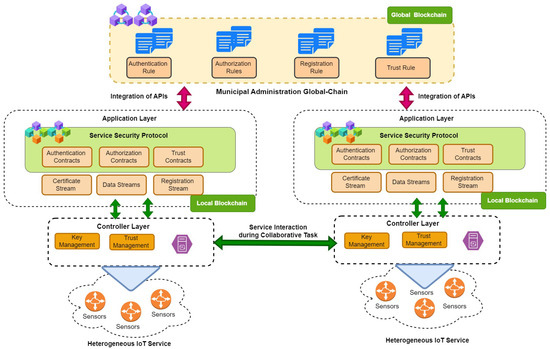

Smart cities use innovative technologies to improve the quality of life in urban areas by integrating the latest technologies. In the case of smart cities, interoperability refers to the fact that smart services can exchange information with each other easily for collaborative tasks [1,2]. The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) devices with interoperable services significantly enhances the level of automation in smart cities, which reduces the need for human intervention [3,4]. Figure 1 visually represents smart cities’ interoperable services, displaying multiple smart services collaborating within the ecosystem. For instance, residents in smart cities optimize their daily routines by integrating smart home and transportation systems, ensuring efficient commutes through synchronized schedules. Such advancements contribute to synchronized and efficient operations across multiple sectors, including transportation, waste management, and public safety, ultimately benefiting smart city residents with a more convenient and sustainable living environment.

Figure 1.

Generic representation of smart cities’ interoperable services, highlighting seamless communication and integration between systems.

Despite the numerous benefits of interoperability with smart services to facilitate various collaborative tasks, ensuring data security during interoperability remains a critical concern. In an automated environment that minimizes human intervention, interoperable services in smart cities encounter heightened risk of exploitation by hackers and malicious entities, exploiting vulnerabilities within the smart city ecosystem. Unauthorized access and data manipulation can lead to severe consequences, emphasizing the need to implement robust security measures to protect critical information and infrastructure [5]. For example, in a scenario where a smart transportation system collaborates with emergency response services, the seamless exchange of real-time data between these services is critical for effective incident management. However, without proper security measures, such as encryption protocols and access controls, this data interchange may become vulnerable to cyber threats, potentially compromising the efficiency and safety of the emergency response.

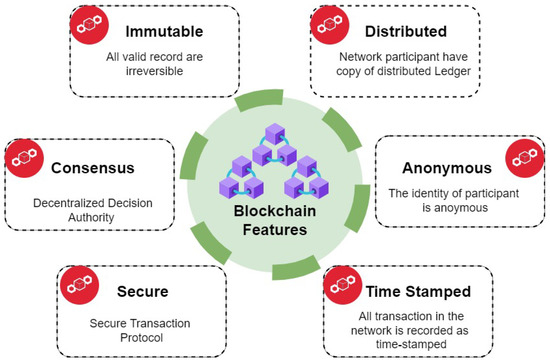

Blockchain technology can greatly enhance the security, transparency, and efficiency of smart cities’ interoperable services. Decentralized management of data, by virtue of smart contracts and the core security features of blockchain-based platforms, avoids unauthorized access and tampering by these technologies [6]. The core features of blockchain are shown in Figure 2. However, the adoption of blockchain technology in smart cities requires careful consideration of scalability, interoperability, and regulatory compliance factors [7].

Figure 2.

Core features of blockchain technology.

While the blockchain platform addresses various core security-related challenges involved in the collaboration of smart services within a smart city-based ecosystem through the support of smart contracts, it also raises concerns about the execution time of smart contracts due to unoptimized code. This is because a major challenge lies in developing real-time decentralized applications that require rapid responses [8]. Optimizing smart contract codes through pre-trained generative AI models can improve the performance and efficiency of smart contracts by reducing unnecessary resource utilization and related costs [9].

Generative AI, particularly via pre-trained models, has the potential to significantly resolve the challenges associated with optimizing smart contracts in blockchain systems. Although there are a multitude of other solutions available to enhance the efficiency of smart contracts, including manual code optimization, layer-2 scaling solutions, and sophisticated compilers, generative AI offers a distinctive advantage [10]. It is capable of analyzing, generating, and optimizing smart contract code with precision, thereby reducing superfluous and computationally intensive steps. Additionally, the integration of generative AI with the fundamental security features of blockchain, such as decentralized verification and cryptographic integrity, fortifies the system. This combination not only improves performance but also cultivates a greater level of confidence in blockchain-based solutions, thereby facilitating their widespread adoption across various industries [11].

1.1. Motivation

This research is driven by the promise of smart cities as a means to enhance the lives of their inhabitants through cooperative endeavors on interoperable services using the best infrastructures and communication technologies available [12]. For example, secure interoperable transportation and weather services combined within smart cities enable the supply of real-time weather information for smart transport users to enhance decision-making in their daily transactions and, thereby, overall effectiveness. Collaborative services are networked and interdependent functions that are put in place to attain specific objectives or meet different needs. Smart services in smart cities thus play an essential role in achieving seamless communication and collaboration between a wide array of smart services [13]. They provide a means of exchanging data, resources, and functional interaction within the networked smart city environment towards improved efficiency, effectiveness, and user experience. However, ensuring the secure and safe deployment of these smart and interoperable services in smart cities is quite a challenging task. Researchers have been exploring this direction by using blockchain technology combined with smart contracts, which support secure and decentralized frameworks for exchanging data and interactions among services. With blockchain, all data remain integral, demonstrating transparency and confidence [14].

Smart contracts automate processes and enforce agreed-upon rules without the requirement of intermediaries. Still, the major challenge is actually optimizing smart contracts. Complex smart contracts with intricate code and resource-extensive execution can somehow hinder scaling and performance issues. These considerations necessitate alternative innovative directions to optimize and make smart contracting efficient, safe, and performant within such dynamic and strongly connected ecosystems that a smart city embodies [15].

1.2. Contribution

This research study explores the integration of blockchain and fine-tuned pre-trained GenAI models to enhance the efficiency of the ITS by addressing challenges related to smart contract transaction overhead and computational efficiency. The key contributions of this work are outlined below:

- The enhancement of an existing framework for interoperable services [16], where the authors proposed an adaptive security framework for interoperable services in smart cities. The authors proposed a solution with the help of the integration of an SDN (software-defined network) along with blockchain and smart contracts.

- The optimization of smart contracts within the existing solution using fine-tuned pre-trained generative AI models. This aims to reduce computational overhead and improve the efficiency of smart contract code in the proposed framework.

- Conducting a comprehensive comparative analysis between optimized and non-optimized smart contract implementations. This analysis evaluates the impact of optimization on key performance metrics, such as computational efficiency, execution time, resource utilization, and overall system throughput.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the background knowledge of the technologies involved in the development of the existing system, along with an overview of the modifications introduced. Section 3 provides a detailed review of the literature supporting the problem statement. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 present an in-depth discussion of the existing system and the proposed modifications, including detailed conceptual diagrams. Section 7 and Section 8 focus on the dataset, its creation, and the implementation of use cases. Finally, Section 9, Section 10 and Section 11 present a comprehensive discussion of the results.

2. Background

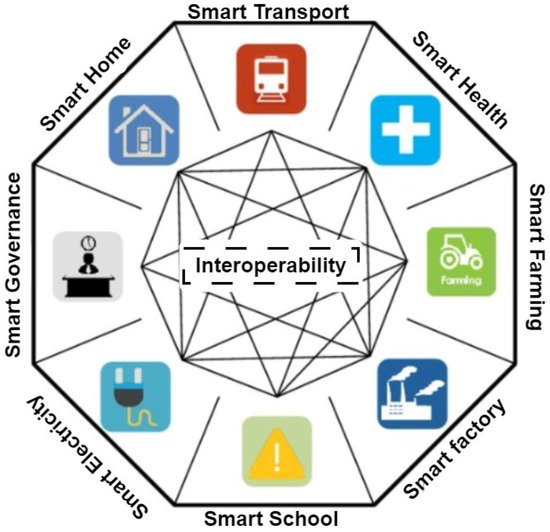

To implement interoperable services in smart cities, it is important to understand what interoperability means in the smart city domain. Interoperability plays a crucial role in facilitating communication and collaboration among diverse IoT devices and services, ensuring efficient cross-domain data exchange and utilization. Different types of interoperability exist, including syntactic and semantic data interoperability and network interoperability [17]. However, this research work places specific emphasis on the significance of syntactic interoperability.

2.1. Syntactic Interoperability

In the context of interoperable services within smart cities, syntactic interoperability assumes a critical role in guaranteeing accurate understanding and smooth data processing across diverse platforms and devices. This capability is vital for enabling effective communication and collaboration among disparate systems [18]. Interoperable services prioritize the early establishment of a shared standard encompassing data exchange formats, communication protocols, and other essential specifications well before the actual interoperability phase. This proactive approach ensures that participating devices and services are aligned and well-prepared to seamlessly interact, facilitating a unified and harmonious exchange of data and functionalities [19,20]. Figure 3 illustrates the typical interoperability architecture among smart services in smart cities. Various smart services collaborate and interoperate with each other. For example, this collaboration involves integrating smart transport and smart home to provide real-time information about the school bus location to users within the smart home environment.

Figure 3.

Syntactic interoperability between smart services.

2.2. Security Challenges in Syntactic Interoperability

Syntactic interoperability establishes the foundation for seamless data exchange among disparate devices and services in smart cities. It also introduces a range of significant security challenges that demand meticulous consideration. As data traverses various platforms and systems, ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of information becomes imperative. Here are some potential security issues with syntactic interoperability:

- Data Integrity [21]: Within the context of smart cities and interoperable services, ensuring data integrity is more important to ensure unchanged and spotless data exchange during interoperability with various other services. In the case of improper security measures, data is susceptible to manipulation, and this results in an erroneous outcome or possibly adverse effects. Implementing robust security measures to counteract risks from data manipulation is among the major challenges.

- Authentication and Authorization [22]: Syntactic interoperability involves the challenge of enabling diverse systems with different access permissions to understand each other’s data. This is a challenge that requires the implementation of robust security measures, including stringent authentication and authorization systems. These are measures that prevent unauthorized access and possible misuse of sensitive data.

- Interoperability with Legacy Systems [23]: It is a difficult task to integrate modern interoperable services with existing legacy systems. Legacy systems are outdated technologies that were developed before the introduction of contemporary interoperability standards. Strategic planning is essential to achieving smooth communication and data exchange between these legacy systems and the new interoperable services.

- Data Privacy [24]: Dealing with smart services based on the Internet of Things raises serious privacy concerns. The increasing gathering and use of personal and sensitive data raises concerns about data privacy and people’s ability to govern their information. To guarantee privacy, there must be strong data protection measures, explicit consent methods, and open data management procedures.

2.3. Blockchain

Blockchain is a revolutionary technology that has transformed the way we store, secure, and exchange data. It acts as a digital ledger, a decentralized and unchangeable system for recording information that forms the foundation for various digital transactions and interactions. Operating on a distributed network of computers, blockchain ensures transparency, security, and trust without relying on intermediaries [25]. In the dynamic realm of smart cities, seamless interaction and data exchange among diverse services and systems are essential for achieving maximum efficiency and functionality. Blockchain technology has emerged as a powerful tool for enhancing interoperable services within smart cities, offering a multitude of advantages that contribute to their sustainable development and improved quality of life for residents. Here are some key benefits of integrating blockchain into smart cities’ interoperable services [26].

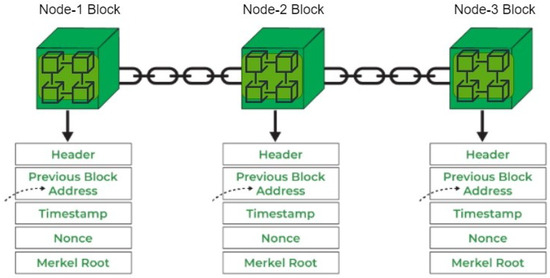

- Decentralized Network [27]: A blockchain operates within a decentralized network of nodes, with each node maintaining a comprehensive copy of the blockchain ledger, as shown in Figure 4. This distinctive decentralized architecture ensures that no single entity wields absolute control over the blockchain. This, in turn, not only fosters transparency and security but also constitutes a fundamental advantage for enabling interoperable services within the intricate framework of smart cities.

Figure 4. Transaction record of blockchain network nodes.

Figure 4. Transaction record of blockchain network nodes. - Consensus Mechanisms [28]: Blockchain consensus mechanisms enable decentralized agreement, bolster security through verification, and ensure tamper-resistant data for interoperable services in smart cities. They enhance efficiency, security, and future-proof urban interactions by fostering trust, strengthening resilience against attacks, and offering scalability options. Selecting the appropriate mechanism is crucial for optimizing smart city services within evolving landscapes.

- Enforce Verification [29]: Blockchain enforces a verification procedure by necessitating consensus among network participants, thereby enhancing the security of data exchanged across diverse interoperable services. This verification effectively reduces the likelihood of fraudulent or unauthorized transactions.

- Smart Contracts [30]: Blockchain platforms enable the use of smart contracts, which are self-executing agreements with predefined rules inscribed on the blockchain. This innovation streamlines interoperable services within smart cities by automating the execution and enforcement of contractual obligations. This not only eliminates the need for intermediaries but also accelerates processes, enhances transparency, and reduces costs.

Blockchain technology combined with smart contracts plays an important role in ensuring security against diverse smart services by guaranteeing secure tamper-proof interoperability among various smart services. Smart contracts are used for the automation of procedures and enforcement of trust, enabling the free flow of data exchange and collaboration with adequate protection for sensitive information. The implementation of non-optimized smart contracts significantly degrades the robustness of smart services with a high amount of computational overhead, reduced responsiveness, and reduced scalability of the system.

Generative AI is emerging as a transformative solution to these problems, offering the ability to efficiently optimize smart contract code. In the context of generative AI models, the performance of smart contracts can be increased, execution overhead may be reduced, and a more resilient and responsive smart city ecosystem would be ensured [31].

2.4. Generative Artificial Intelligence

Pre-trained generative AI models are sophisticated machine learning systems that are developed to generate human-like content, such as text, images, and even code. They are trained on enormous datasets covering a wide range of domains, so they learn complex patterns, relationships, and structures in data. Being “pre-trained” means they have already learned an enormous amount of general knowledge, which can then be fine-tuned for specific tasks [32]. This occurs via machine learning models trained on an enormous range of datasets to generate a range of outputs, including text, photos, audio, code, and even designs. Generative artificial intelligence distinguishes itself by being able to adapt and innovate by understanding complex settings and generating contextually relevant results [33,34]. Some of the popular generative AI models for text-to-text generation are listed below:

GPT (Generative Pre-Trained Transformer): GPT is an open-source family of autoregressive language models designed for text generation [35]. OpenAI developed it with its architecture based on the transformer model, using unsupervised learning on large datasets to predict the next word in a sequence. Its models are fine-tuned to a wide range of applications, including creative writing, summarization, question-answering, code optimization, and many more [36]. The following are the variants of the GPT model:

- GPT-2 was a landmark generative AI model that introduced a transformer-based architecture that could generate coherent and contextually relevant text. With 1.5 billion parameters, GPT-2 showed the power of large-scale unsupervised learning, outperforming other models in text completion, summarization, and basic programming tasks [37].

- GPT-3 was considerably more extensive than its foundation, GPT-2, scaling up to 175 billion parameters, thus making it one of the most advanced generative AI models of its time. This huge jump in size allowed GPT-3 to generate highly sophisticated and contextually accurate text across a wide range of domains. It showed exceptional versatility, excelling in text generation, creative writing, coding tasks, and even logical reasoning [38].

- GPT-4 is built upon the foundation of GPT-3 but with substantial advancements in reasoning, contextual understanding, and multi-modal processing. It provides improvements in handling larger contexts and performing complex multi-turn interactions with more coherence and depth. GPT-4 also shows excellence in technical domains, especially in code generation, debugging, and optimization, and expanded support for programming languages such as Python, C++, and Solidity. Its refined architecture and vast training data made it capable of answering more complex questions, making it the preferred choice for tasks that demand advanced reasoning, logical problem-solving, and domain-specific expertise [39].

Bidirectional Encoder (BERT): BERT is a pre-trained language model introduced by Google, focusing on the training of text in both directions, considering left and right context simultaneously [40]. However, vanilla BERT is not well-suited for code generation tasks as it is not designed for sequential token generation. Unlike autoregressive models such as GPT, BERT excels in understanding and encoding input but lacks the architecture necessary for producing syntactically and semantically coherent code outputs [41]. The variants of BERT are as follows:

- BERT-Base: The base BERT model (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), developed by Google, is a pre-trained language model designed to understand natural language using deep bidirectional representations. It consists of 12 transformer encoder layers, 12 self-attention heads, and approximately 110 million parameters. Unlike traditional language models that read text either left-to-right or right-to-left, BERT reads in both directions simultaneously, allowing it to grasp the full context of each word in a sentence. It is trained on two core tasks: Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where random words are hidden and predicted, and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP), which aids in understanding relationships between sentences [40].

- BERT-Large: The BERT-Large model is an extended version of Google’s Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), designed to capture even deeper contextual understanding of language. It consists of 24 transformer encoder layers, 16 attention heads, and has approximately 340 million parameters, significantly more than the base BERT model. Like its smaller counterpart, BERT-Large is trained using a bidirectional approach with Masked Language Modeling (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) as its core training objectives [42].

- DistilBERT: A lightweight, distilled version of BERT, designed to reduce model size and improve inference speed while retaining most of the original performance [43].

T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer): A unified framework developed by Google that casts all natural language processing tasks into a text-to-text format, including translation, summarization, and question-answering. Its versatility comes from this uniform format, allowing it to handle a wide range of language understanding and generation tasks with high accuracy [44]. The following are the variations of T5 Transformer:

- T5-Base: This model contains approximately 220 million parameters and is suitable for general NLP tasks under moderate computational constraints. It balances performance and efficiency.

- T5-Large: With about 770 million parameters, this version achieves higher accuracy in complex language tasks such as summarization and translation but requires more resources.

- mT5 (Multilingual T5): Designed for multilingual applications, mT5 is trained in 101 languages and is available in multiple sizes (small to XL), making it highly effective for translation and cross-lingual tasks.

Codex is a specialized AI model developed by OpenAI and trained on both natural language and a large corpus of publicly available source code. It powers tools like GitHub Copilot and is capable of generating syntactically correct code in multiple programming languages. Codex is particularly relevant for smart contract development due to its code generation capabilities and contextual understanding of programming logic [45]. This version is fine-tuned from GPT-3 using a large corpus of public source code. It supports a variety of programming languages, including Python, JavaScript, and Solidity, and powers tools like GitHub Copilot.

Table 1 below highlights the most popular generative AI models, including their key functionalities and notable variants. In this research article, we focus on GPT-based models, specifically GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4, due to their proven effectiveness in code generation tasks, particularly in languages such as Python and Solidity, which aligns closely with our objective of generating smart contracts.

Table 1.

Generative AI models, features, and renowned variants.

Table 1.

Generative AI models, features, and renowned variants.

| Model | Features | Renowned Variants |

|---|---|---|

| GPT [46] | Text generation, completion, summarization | GPT-1, GPT-2, GPT-3, GPT-4 |

| BERT [47] | Contextual embeddings, NLU | BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT |

| T5 [44] | Text-to-text, translation, summarization | T5, mT5 |

| Codex [45] | Code generation, multi-language support | Codex (OpenAI), GitHub Copilot |

2.5. Generative AI for Smart Contract Optimization

GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 are transformer-based language models developed by OpenAI. They have shown spectacular capabilities in text generation that looks human-like, as well as supporting a range of NLP tasks. All three models rely on the transformer architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms for capturing long-range dependencies in data, making it suitable for structured content, including programming code, understanding, and generating. In this work, we selected the GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models for code optimization in terms of code complexity optimization and code loop optimization.

Each model supports multi-language generation, including Python, C, C++, and Solidity, which makes them ideal for cross-language analysis and optimization tasks. They can generate syntactically and semantically correct code snippets, which are helpful in developing smart contracts that adhere to best practices in terms of code complexity and loop optimization. Specialized models like CodeBERT can handle similar problems, but we used GPT-2 and GPT-3 for the following reasons:

- Generating Optimized Code: Each model is very good at generating optimal code, making them suitable for the rewriting of loops to reduce complexity and execution cost. For example, they can flatten nested or unbounded loops into more efficient constructs and reshape code to have fewer state changes.

- Efficiency of Lightweight Variants: With the light variants, GPT-2 and smaller GPT-3 models, we can achieve a good balance between computational efficiency and performance. This is particularly valuable when targeting tasks with limited computational resources or rapid turnaround requirements.

- Domain Adaptability: The general-purpose code understanding capabilities of GPT models can be fine-tuned using a customized dataset of smart contracts in the Solidity domain, enabling them to detect inefficiencies due to loops and redundant variables. Thus, they are tuned toward the exact issues at play within the domain of gas optimization within blockchain settings.

2.6. Generative AI Integration with Blockchain

Blockchains are rapidly being integrated into the smart city ecosystem to enhance interoperability across different smart city services [48]. However, the integration of this technology is facing severe challenges that relate to efficiency, scalability, and cost. One of the major challenges is that the code associated with blockchain transactions is complex in nature, especially when invoking or deploying smart contracts [49]. The computational complexity and redundancy associated with smart contract code increase code complexity and high execution costs further [50]. These challenges make the process more time-consuming and less cost-efficient. Generative AI promises to optimize the performance of smart contracts, hence reducing redundant code items. This will in turn minimize the complexity of the code and improve the overall efficiency. This will make the blockchain infrastructure much more streamlined, robust, and suitable for smart city ecosystems.

- Role of Generative AI in Smart Contract Optimization: Fine-tuned generative AI models can be effectively applied to optimize smart contract code, automating the process of improving efficiency. These models analyze existing smart contracts for inefficiencies, such as redundant computations, unnecessary logic, and bloated code. Once identified, AI creates optimized versions of the code that retain the same functionality but impose less computational load on the blockchain network [51].

- Reduced Computational Overhead: One of the fundamental benefits of embedding AI with blockchain is reducing computational overhead. In traditional blockchain networks, a substantial number of nodes are typically utilized for transaction processing and verification, in turn involving a great deal of computational usage [11].

3. Related Work

The concept of “smart cities” has gained significant momentum as urban areas worldwide strive to leverage advanced technologies and data-driven solutions to enhance efficiency, sustainability, and the overall quality of life for their residents [52,53,54]. However, achieving syntactic interoperability across domains and services remains a key challenge in managing and executing smart city efforts. Ensuring secure and effective communication is crucial for achieving seamless interoperability of smart services in smart cities and enhancing the user experience. As smart cities continue to grow, the need for trustworthy and secure communication becomes increasingly important to protect against online threats, unauthorized access, and data manipulation. Adaptive security measures are required to swiftly address emerging risks and challenges while upholding data privacy, accuracy, and accessibility [55,56,57]. The authors in [58] discuss the challenges introduced by the diverse nature of smart city systems in implementing effective authentication mechanisms for interoperable services in smart cities. The lack of standardization and interoperability among different services and systems can also result in security vulnerabilities and impede the secure exchange of data and resources. Kumar et al. [59] explore key management challenges in smart city systems, emphasizing the need for a secure and efficient system to prevent unauthorized access and data breaches. They propose a blockchain-based key management solution for secure data interchange in smart cities, which is crucial for ensuring reliable and safe interoperable services. Harbi et al. [60] emphasize the issues associated with a lack of standardization and compatibility regarding various services and systems across multiple authentication schemes in smart cities. They present a dynamic key management system that adapts to changing needs and developing technologies, allowing the safe and efficient interchange of data and resources across smart cities’ many services and systems.

Blockchain technology integration into ITSs for useful solutions to large-scale urban transportation network management challenges, particularly in security, transparency, and efficiency. However, this is not without its limitations. One of the major concerns in blockchain transactions is the issue of high gas fees, a matter that makes the deployment and execution of smart contracts a costly and less scalable proposition in real-time environments like ITSs. Further, the computational complexity inherent in blockchain systems can impair responsiveness as it also demands more latency to manage dynamic traffic conditions and large volumes of transactions in smart cities. The authors in [61] propose a new consensus mechanism called PoM for a new Secure Service Level Agreement Management framework based on blockchain technology. It also provides details of a prototype implementation of the consensus algorithm and the SSLA governance framework. AIaWorld et al. [62] propose a solution that addresses the issues of resource wastage and lack of computing power between nodes in the traditional Proof of Work (PoW) mechanism. The paper introduces a novel consensus mechanism, CPoS (Committee Proof of Stake), which aims to enhance the efficiency and liquidity of blockchain systems. The proposed architecture is based on forging committees and forging groups, which are designed to establish a decentralized, independent, and secure Internet trust system. However, since the solution relies on forging committees and groups to validate and confirm transactions, there may be concerns about centralization or potential manipulation of the consensus process. Additionally, interactions between the mainchain and sidechains could lead to security issues or conflicts across different chains. The authors in [63] present a new consensus mechanism called Proof of Random Count (PoRCH), using a custom mining node selection system. The work beyond this novel consensus mechanism involves an experimental prototype system, collecting data that utilizes blockchain technology. The performance evaluation of the prototype supports the possibility of applying blockchain technology. The performance assessment relies on a simple demonstration with only a few nodes and measured data.

Gao et al. [64] proposed a blockchain-based privacy-preserving payment solution for V2G networks that allows data sharing while protecting sensitive user information. A blockchain-based payment solution is proposed as a means of addressing the security concerns associated with data sharing in V2G networks. It uses a decentralized anonymous payment mechanism based on Hyperledger. The proposed method might cause a performance bottleneck. In order for EVs to adapt to this mechanism, an attractive pricing policy needs to be implemented, and the privacy demand will vary depending upon the user’s requirements. Liu et al. [65] propose a solution that combines artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technologies for smart transportation systems to prevent cyberattacks. The proposed solution leverages AI and blockchain to securely store maintenance data for public transportation, ensuring the integrity of related transactions. It utilizes a deep learning-based model that incorporates an autoencoder and a multi-layer perceptron, alongside hash blocks that are signed and verified by the blockchain. However, the integration of the deep learning model and smart contracts may introduce transaction overhead, potentially impacting system efficiency. The authors in [66] present a solution specifically targeted at driverless electric vehicles. This solution processes requests in a distributed manner, and, in order to reduce the request latency overhead, software-defined networks have also been utilized. It provides a secure energy trading mechanism designed for unmanned vehicles that is decentralized in nature and uses energy coins for energy trading and also provides minimal overhead by utilizing SDN. The consensus mechanism was the only major blockchain component utilized, and the performance evaluation was carried out in a controlled environment. Maskey et al. [67] propose a blockchain-based solution designed to detect outliers and prevent cyberattacks while preserving data integrity. Outlier detection is performed using machine learning models. To ensure data integration, secure transactions, and secure data storage, a decentralized approach combined with outlier detection is employed. The integration of blockchain and machine learning provides a decentralized environment capable of detecting outliers effectively [68,69]. However, the performance evaluation is conducted on a small scale, with the proposed mechanism relying on the blockchain’s default consensus mechanism, which could result in overhead when scaled up.

The authors in [70] propose a solution that provides a blockchain-based sustainable Global Credential Utility (GCU) mechanism that provides a decentralized environment and utilizes ISM, fuzzy, and DEMATEL methods to filter out unwanted attributes. The expert committee only includes transportation experts. Better results could be achieved if the committee includes experts from electronics, blockchain, and other fields. The fuzzy set theory may still contain errors that could affect the research results if removed and the core techniques of blockchain are not utilized. Sahal et al. [71] propose a solution for an intelligent transportation system by combining blockchain with digital twins. The DT model simulates system behavior in real time to optimize performance, identify potential problems, and test various scenarios. To overcome DTs, centralize mechanisms, and prevent data breaches, a ledger-based collaborative DT framework is used that provides a decentralized environment and decisional-based real-time data analytics. Performance evaluations are absent, and the proposed mechanism primarily targets DTs and does not explore the blockchain’s core techniques in depth.

The authors in [72] propose a decentralized data management solution that utilizes blockchain and the Internet of Things to overcome data security and data vulnerability issues. It is a decentralized system for managing data that makes use of a Hyperledger fabric-based data architecture and offers safe transactions. The proposed mechanism indicates that the waiting time for the channel to open might be 3.76 min, but this could change if conducted on a larger scale with the Hyperledger fabric, the only blockchain component used. In [73], the authors propose a blockchain mechanism that allows private data sharing and secure transactions through PrivySharing. Also, with smart contracts in an access control list, this approach is decentralized in nature. The proposed solution is based primarily on the functionality of blockchain as a smart contract.

In [74], the authors propose a blockchain-based solution in the ITS by introducing Proof of Pseudonym (PoP), which is a blockchain component for identity verification. PoP mechanism was optimized through modification of its pseudonym-shuffling process in order to provide better efficiency regarding consensus time and memory compared to other consensus mechanisms. The authors of [9] introduce AI, which, according to them, solves all the key blockchain challenges: scalability, security, and privacy. They describe how AI can be integrated with blockchains and then provide in greater detail an illustrative example of how this may improve network efficiency in a case study, which demonstrates increases both in throughput and latency reductions. The authors in [75] provide an illustration of how artificial intelligence in the likeness of OpenAI’s ChatGPT may enable consumers to write their own contracts. While AI is widely adopted today in the practice of law for the review and management of business contracts, this paper takes one step further to explore the possibility of generating a fully formed contract from scratch based on user prompts. Table 2 provides a summary of the existing literature along with the proposed solution features, highlighting the novelty of our approach.

Table 2.

Summary of the literature review uses (✓) to indicate features that are included and (✗) to indicate features that are excluded in the listed papers.

Table 2.

Summary of the literature review uses (✓) to indicate features that are included and (✗) to indicate features that are excluded in the listed papers.

| Paper | Security | Smart Contract | GenAI Solution | Technique Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | AI for blockchain, addressing scalability, security, and privacy, with a case study demonstrating improved throughput and latency. |

| [63] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Proof of Random Count (PoRCH) with custom mining node selection to reduce network overhead. |

| [64] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Privacy-preserving payment solution for V2G networks using Hyperledger and decentralized anonymous payments. |

| [65] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | AI (autoencoder, multi-layer perceptron) with blockchain for secure maintenance data in public transport. |

| [66] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Secure energy trading for unmanned vehicles using SDN and energy coins in a decentralized environment. |

| [67] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Blockchain-based outlier detection for cyberattack prevention, using ML for secure data storage. |

| [70] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Blockchain-based Global Credential Utility (GCU) using ISM, Fuzzy, and DEMATEL methods for attribute filtering. |

| [71] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Blockchain Digital Twin (DT) for real-time performance optimization and secure decision analytics. |

| [72] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Decentralized data management using Hyperledger Fabric for secure IoT-based data transactions. |

| [73] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | PrivySharing with ACLs and smart contracts for private data sharing and monetization. |

| [74] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Optimized Proof of Pseudonym (PoP) to improve consensus by minimizing pseudonym shuffling overhead. |

| [75] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Use of GPT-4 to generate functional, enforceable contracts from scratch, enhancing access to legal services. |

| Proposed Solution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Comprehensive integration of GenAI with blockchain-based security framework, addressing security, scalability, privacy, and smart contract optimization through GenAI-based models. |

While generative AI offers significant promise in automating smart contract generation and optimization, several non-generative AI and formal methods have been instrumental in ensuring the correctness, security, and efficiency of smart contracts, especially in safety-critical systems [76]. These approaches offer different advantages, ranging from verifiability and interpretability to runtime analysis and logic enforcement, making them complementary to generative AI in many blockchain-based applications. Table 3 provides a comprehensive summary of optimization techniques, including generative AI, formal methods, and manual/static analysis tools, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and applicability in smart contract development.

Table 3.

Comparison of smart contract optimization techniques.

Table 3.

Comparison of smart contract optimization techniques.

| Optimization Technique | Tools/Methods | Strengths | Weaknesses | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative AI-based [61,77] | GPT-2, GPT-3, Codex, ChatGPT | Fast, scalable, reduces manual coding, adapts to multiple languages | Limited interpretability, risk of unsafe or incorrect outputs without supervision | High |

| Formal Methods [78,79] | KEVM, Coq | Provides mathematical proofs of correctness, strong safety guarantees | Complex and time-consuming, steep learning curve | Very High (safety-critical) |

| Symbolic Execution [80,81] | Mythril, Slither | Identifies vulnerabilities like reentrancy, overflow, timestamp issues; fast automation | May produce false positives; limited to predefined rules | Medium to High |

4. Existing Framework

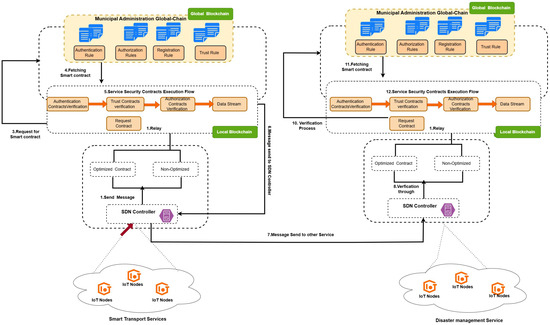

The existing framework [16], as shown in Figure 5, incorporates a strong security architecture to make it feasible to provide collaborative services in municipal smart cities, especially by the incorporation of software-defined networking, blockchain technology, and smart contracts. It aims to overcome serious challenges in heterogeneous IoT networks, including scalability, security, and trust issues. A three-layered architecture comprises (1) the perception layer, which acquires environmental data; (2) the controller layer, responsible for implementing SDN to manage traffic, verify trust, and ensure secure communication; and (3) the application layer, where decentralized applications are hosted alongside security policies. The key feature of the framework is its use of SDN to simplify IoT network management by separating the data plane for packet forwarding from the control plane for routing decisions, thus allowing scalable and programmable interactions. The proposed security framework for interoperable services in smart city ecosystems integrates MultiChain blockchain to provide decentralized, immutable, and transparent data management, thereby ensuring data integrity and security. It uses a combination of local and global blockchains, where intra-network tasks are handled by the local blockchain and inter-network policies are enforced by the global blockchain. Smart filters are used in MultiChain to validate transactions and data while performing collaborative tasks. Three kinds of smart contracts will be deployed within the framework, namely authenticity contracts for authenticating the legitimacy of IoT devices, trust contracts for managing and updating trust scores of devices, and authorization contracts for access control based on the trust indexes. However, the implementation of smart contract execution in this framework is manual, requiring a responsible entity to write and deploy smart contracts that govern authenticity, trust, and authorization policies.

Figure 5.

Existing proposed security framework.

The existing framework uses a single smart contract that performs the automation of security implementation within the framework. This is the smart contract performed in Python that represents the central component that enforces security policies and handles secure interactions in the framework, known as the service security contract. However, the current implementation is non-optimized and results in inefficiencies in execution time, resource use, and computational overhead. Despite these limitations, the smart contract effectively integrates with the security framework, allowing automated decision-making and policy enforcement. Further optimization is required to enhance its performance, reduce processing costs, and improve the overall system efficiency while maintaining robust security mechanisms. Algorithm 1 demonstrates the implementation of a smart contract within the existing security framework for smart city services. It ensures secure authentication, authorization, and trust-based access control when multiple services share data. In this framework, various smart city services, such as transportation, weather, and telecommunication services, exchange information to execute the use case of disaster management, necessitating strict access control mechanisms. The authentication process verifies users based on their address and password before allowing access to any service. If the user is not registered or provides incorrect credentials, access is denied. Once authenticated, the authorization mechanism decides whether the user has permission to access a specific service or dataset. The trust factor also plays a significant role in decision-making: users with a trust level below the required threshold are restricted from accessing sensitive services.

| Algorithm 1 Non-Optimized Authentication, Authorization, and Trust Mechanism. |

|

Proposed Modification in Existing Framework

In the existing framework, the local blockchain layer, the service security protocol operates in two different modes:

- Administrative Mode: Designed for distributed administrative nodes. These nodes are responsible for enforcing authentication, authorization, and trust rules to govern decentralized applications. The rules for decentralized applications are uploaded manually.

- Non-Administrative Mode: Designed for decentralized applications. These nodes integrate the rules enforced by administrative nodes into their applications and also perform security verification to ensure the decentralized applications function securely and efficiently.

The administrative nodes are based on a static smart contract deployment with non-optimized code, which limits flexibility and adaptability in a dynamic smart city environment. In this regard, we propose a generative AI approach where the generation of smart contracts becomes dynamic and tailored to the evolving needs of multiple interoperable services. Services such as transportation, weather monitoring, and telecommunications can define their authentication, authorization, and trust requirements. The generative AI model then processes these inputs and automatically generates an optimized smart contract, ensuring efficiency, scalability, and security. This approach not only reduces human effort in contract development but also improves adaptability, allowing real-time customization of security policies based on service-specific needs.

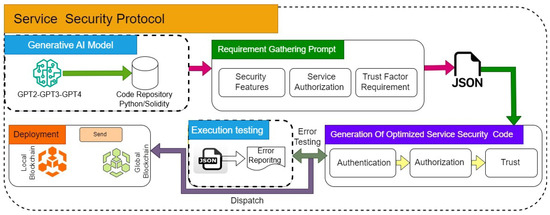

Figure 6 shows the modification of the existing framework service security protocol mechanism. The new system uses Generative AI models such as GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT4 to produce optimized Python-based smart contracts or Solidity code with real-time needs from multiple interoperable services. These services, like transportation, weather monitoring, and telecommunications, define authentication, authorization, and trust specifications, and the AI models are structured into a JSON-based format for processing. Several rounds of refinement iterations in the framework occur so that the smart contracts generated by the framework will be efficient, scalable, and adaptable to particular security needs with minimum manual effort in the dynamic environment of a smart city.

Figure 6.

Modifications of service security protocol.

- Generative AI Integration: The updated framework uses GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models to automate the creation of smart contracts. The process starts with fine-tuning these models using relevant datasets, enabling them to generate optimized Python and Solidity smart contracts tailored to the system’s requirements. This approach eliminates the need for manual coding and minimizes human errors, ensuring higher accuracy and faster execution.

- Requirement Gathering and Code Generation: Security requirements, such as authentication, authorization, and trust evaluation, are captured through a structured prompt-based input. This data is converted into JSON format and serves as the foundation for generating optimized security code. The modular structure of the generated code ensures adaptability and compatibility with various IoT- and blockchain-based systems.

- Execution Testing and Error Feedback: A critical addition to the framework is the Execution Testing module. The generated smart contract undergoes rigorous testing, including compilation checks and functionality tests. If errors are detected, the system sends feedback to the AI models, which regenerate the smart contract by addressing the identified issues. This iterative loop ensures that the final output is error-free and ready for deployment.

- Enhanced Deployment: Once validated, the optimized smart contract is deployed either to a local blockchain or a global blockchain environment, depending on the system’s operational scope. This deployment process is streamlined and secure, ensuring that the smart contracts function as intended in real-world scenarios.

- Continuous Improvement: The framework emphasizes ongoing monitoring and feedback. After deployment, the system collects performance metrics and potential issues, feeding them back into the AI models for future refinements. This closed-loop approach ensures that the framework evolves dynamically to meet emerging security challenges.

5. Dataset Discussion

We developed a custom dataset specifically tailored for fine-tuning generative AI models like GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 to optimize smart contracts by reducing execution complexity and transaction costs. The dataset is designed to address key inefficiencies in smart contract code, particularly focusing on loop optimization and redundant variable reduction as these are among the critical contributors to the increased execution costs of smart contracts based on Python and Solidity code.

5.1. Dataset Pipeline for Optimizing Smart Contracts with GenAI

We developed a custom dataset specifically tailored for fine-tuning generative AI models such as GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4, aimed at optimizing smart contracts by reducing execution complexity and transaction costs. The dataset addresses key inefficiencies in smart contract code, particularly focusing on loop structures and redundant variable usage, which are critical contributors to increased computational cost in both Python- and Solidity-based implementations.

To construct the dataset, we began with a baseline access control contract written in both Python and Solidity. Using generative AI models, we programmatically generated 500 syntactic and semantic variants for each language. These variations were designed to introduce code smells, redundant computations, and gas-expensive patterns while preserving the core logic of the contract, thereby capturing a range of inefficient coding patterns. Our dataset is represented as shown in Equation (1):

where

- : Code snippet (input).

- : Label, where for optimized code and for non-optimized code.

- N: Total number of examples in the dataset.

To ensure the optimized variants are both computationally efficient and maintainable, we applied transformations that minimize redundant operations, eliminate unnecessary variable assignments, and enhance loop efficiency. These optimizations were validated using existing online tools such as PyLint [82] for Python and Solc [83] for Solidity. These tools facilitate static code analysis and refinement by detecting inefficient patterns and applying consistent automated improvements. Table 4 summarizes the optimization tools used publicly in optimization pipeline.

Table 4.

Python and Solidity code optimization tools.

Table 4.

Python and Solidity code optimization tools.

| Tool | Description | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Python Optimization Tools | ||

| PyLint [84] | Static code analyzer for Python | Code quality, Execution speed |

| PyBADS [85] | Auto code formatter for better readability | Readability |

| Solidity Optimization Tools | ||

| Solc [86] | Solidity compiler with automatic optimization passes | Gas efficiency, Bytecode optimization |

| Slither [81] | Static analysis framework for Solidity smart contracts | Vulnerability detection, Code quality |

| Mythril [80] | Security analysis tool using symbolic execution | Security analysis, Loop inefficiencies |

5.2. Example Dataset

The dataset represented as follows:

In this dataset, a label of ‘1’ denotes optimized code, whereas a label of ‘0’ signifies non-optimized code. The optimizations primarily focus on

- Loop Efficiency: Using list comprehensions or direct function calls to reduce unnecessary iterations and memory overhead.

- Variable Minimization: Eliminating redundant variable assignments that increase memory usage and reduce readability.

- Computational Complexity Reduction: Ensuring that each code snippet executes with minimal operations while maintaining functionality.

Algorithm 2 demonstrates the implementation of a smart contract labeling pipeline that automates the classification of source code as either “Optimized” or “Not Optimized.” The process begins by reading each row from a CSV file containing code snippets and their corresponding programming language (Python or Solidity). Depending on the language, the pipeline performs static analysis using appropriate tools: PyLint for Python and Solc with Slither for Solidity.

| Algorithm 2 Data Labeling Pipeline for Smart Contract Optimization. |

|

For Python code, the pipeline evaluates code quality based on PyLint’s score, warning count, and error count. If the score is above a predefined threshold (e.g., 8.5), warnings are minimal, and no errors are detected, the code is labeled as optimized. Similarly, for Solidity code, successful compilation via Solc and zero security warnings from Slither are used as criteria for labeling the code as optimized. Each code sample is then annotated with extracted metrics and its corresponding label, and the final labeled dataset is exported in JSON format for downstream tasks, such as fine-tuning generative AI models or model evaluation. The default thresholds and annotation logic used in the labeling process are summarized in Table 5. These criteria are used to ensure consistency and objectivity when categorizing smart contract code as either optimized or not optimized.

Table 5.

Threshold criteria and annotation rules for code labeling.

5.3. Fine-Tuning Generative AI Models for Smart Contract Optimization

We fine-tuned the existing GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models, focusing on optimization in smart contracts. Although these models are known for generating optimized code, we have tuned them according to our specific environment requirements. Algorithm 3 shows the implementation of the fine-tuned process. GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 fine-tuning for smart contract optimization is a multi-step process to improve the code in various regards.

| Algorithm 3 Fine-Tuning GPT-2/GPT-3/GPT-4 for Smart Contract Optimization. |

|

The first part involves preparing the dataset with labels representing both optimized and non-optimized smart contract code, leaning toward efficient loop structures and elimination of redundant variable usage. The tokenized dataset is then used in a pre-trained model that acts as the base for fine-tuning. A custom loss function is designed that penalizes redundant variables and inefficient loops to make sure the model learns how to generate optimized code. In training, the model iterates through the dataset in batches and computes loss while adjusting parameters via gradient descent. The process repeats for multiple epochs to improve the ability of the model to generate efficient smart contract code. After being trained, it is tested upon a validation set to see whether the loop has been improved along with the number of variables that have been reduced. The model is saved with fine-tuning and is utilized for producing optimal smart contract code in real-world applications. The model is allowed to consistently provide high-quality and performance-optimized code with minimized computational overhead and redundancy.

5.4. Performance Metrics for Evaluating Pre-Trained Generative AI Models

The main performance metrics to assess generation quality in generative AI models include BLEU score, precision, recall, and F1-score, among others.

- BLEU scores measure the quality of code generated relative to a reference code by correlating n-gram overlap and accuracy. High BLEU scores imply higher similarity to expected structures and codes. The basic equation according to [87] for BLEU score is presented in Equation (2):whereThe BLEU score is a metric used to evaluate the quality of generated code (or text) by comparing it with a reference output. It calculates the geometric mean of modified n-gram precision () across different n-gram lengths (typically up to 4), weighted equally by . To prevent short outputs from scoring artificially high, a brevity penalty (BP) is applied based on the ratio of candidate length (c) to reference length (r). A higher BLEU score indicates greater similarity to the reference code in terms of structure and content.

- Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions. It tells us what proportion of the items labeled as positive by the model are actually correct. High precision means that, when the model predicts a positive class (e.g., a correct code snippet, a bug, or a class label), it is usually correct. Equation (3) presents the formula for calculating precision [88]:

- Recall, also known as sensitivity or true positive rate, is the model’s ability to capture all the positive instances. It computes the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. Equation (4) presents the formula for calculating recall [88]:

- The F1-score is the harmonic average of precision and recall, where both false positives and false negatives are considered. It is particularly useful when the class of interest is not uniformly distributed. Equation (5) presents the F1-score calculation formula [88]:

Table 6 and Table 7 present the performance metrics of our fine-tuned GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models, offering a comparative analysis of their effectiveness in generating accurate and well-structured code in both Python and Solidity. The BLEU score, precision, recall, and F1-score for the GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 comparisons indicate that the performance of these models differs significantly when it comes to code generation. For the performance matrix of Python, we noted that the BLEU score for GPT-4 is 0.81, for GPT-3 0.75, and GPT-2 0.64. This shows that GPT-4 produces syntactically and semantically correct code more than GPT-2 and GPT-3. It indicates that GPT-4 has a better understanding of the programming structures and yields more refined outputs. Additionally, GPT-4 shows higher precision (0.85) than GPT-2 and GPT-3, which means that it produces fewer incorrect or unnecessary code tokens, and therefore more reliable outputs. A similar trend is observed in both the recall and F1-scores, further supporting GPT-4’s superior performance.

Table 6.

Python code performance metric comparison of GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models.

Table 7.

Solidity code performance metric comparison of GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 models.

From the performance metrics for Solidity, we observed a similar pattern of results as in the Python case, with GPT-4 outperforming GPT-3 and GPT-2. However, the overall performance metrics showed slight degradation across all models. This decline can be attributed to the fact that Solidity is a domain-specific language with stricter syntax rules, limited training data, and a less diverse codebase in comparison to Python, which affects the models’ ability to generate accurate and optimized code.

6. Use-Case Implementation and Experimental Testbed Discussion

To evaluate the practicality and efficacy of the existing adaptive security framework, the authors integrated the collaborative weather emergency response services into the framework. This use case serves as an illustrative scenario, demonstrating the seamless integration of three Python-based client–server services: the smart disaster management service, the smart ambulance service, and the smart weather service. The Python client–server applications utilize standard APIs, namely OpenStreetMap and OpenWeatherMap, to seamlessly integrate the use case into the SDIoT architecture.

- OpenWeatherMap [89]: The OpenWeatherMap API grants us access to real-time weather data, serving as a critical component for integrating current weather information into our emergency response systems. This data encompasses essential parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and precipitation, which are pivotal for making well-informed and timely decisions during emergency situations. By leveraging this API, we enhance the effectiveness of our emergency response services in smart cities, prioritizing the safety and well-being of residents, especially during adverse weather conditions. Table 8 presents the detailed features and parameters utilized in developing the smart weather service.

Table 8. OpenWeatherMap features.Table 8. OpenWeatherMap features.

Table 8. OpenWeatherMap features.Table 8. OpenWeatherMap features.Features Parameter Description Current Location [90] Output parameter

1. Latitude Position

2. Longitude Position1. Provides current locations of weather conditions, such as local drizzle, heavy rain, and urban flooding.

2. We used Weather.id feature, responsible for providing the current and predicted data of rain and flood conditions.Current Air Pollution [89] Output parameter

1. Air Index

2. Predictive data Input parameter

3. Current position1. The Air Pollution API offers up-to-date, predictive, and past air pollution data for any requested location.

2. It also provides the details of specific gases, such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen monoxide in the environment. - OpenStreetMap API [91]: The OpenStreetMap API is a valuable resource for geospatial data, offering detailed maps, routes, and location-specific information. As an open-source platform, it allows users to access and contribute to a vast database of geospatial data, including roads, structures, and points of interest. One of the key advantages of the OpenStreetMap API is its ability to provide detailed maps for different regions, featuring comprehensive information on roads, structures, and other features. This functionality is especially beneficial for emergency response services as it enables them to swiftly identify the locations of emergencies and plan the most efficient routes for rapid response. Table 9 presents the detailed features and parameters utilized in developing the smart ambulance service.

Table 9. OpenStreetMap features.Table 9. OpenStreetMap features.

Table 9. OpenStreetMap features.Table 9. OpenStreetMap features.Features Parameter Description Current Location [92] Output parameter

1. Latitude Position

2. Longitude Position1. Overpass API is a powerful tool that allows users to extract specific data from the OpenStreetMap database. Best Route [93] Output parameter

1. Best Route Input parameter

2. Current position1. The GraphHopper API is a powerful routing engine that utilizes OpenStreetMap data to calculate the most efficient route between two locations.

6.1. Testbed and Experimental Setup

To evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of existing security frameworks using both optimized and non-optimized Python- and Solidity-based smart contracts, we have successfully established a robust testbed and experimentation environment for an interoperable smart city service network. This setup was implemented in two distinct ways: one based on the original MultiChain-based framework (as used in the base paper) and the other using a replicated Solidity-based version deployed on an Ethereum-compatible environment through Python’s Web3 library. Furthermore, the implementation of the proposed security framework, along with the use case, was simulated using the Cooja Simulator [94]. Cooja (Cooja Simulator) is a powerful tool specifically designed for simulating wireless sensor networks (WSNs) and Internet of Things (IoT) networks. As an open-source tool, Cooja enables the simulation and testing of network protocols, applications, and devices in a virtual environment. It is built on the Contiki operating system, which is tailored to meet the unique requirements of low-power and resource-constrained IoT devices [95]. Cooja supports the simulation of various network protocols commonly used in WSNs and IoT networks, including IPv6, RPL (Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks), 6LoWPAN (IPv6 over Low-Power Wireless Personal Area Networks), and CoAP (Constrained Application Protocol) [96]. This extensive support allows developers to comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and behavior of these protocols under diverse network conditions and scenario types. By integrating the Cooja Simulator into our testbed, we are able to conduct thorough and accurate evaluations of our proposed security framework in a controlled virtual environment [97].

In the existing framework, the authors implemented their solution using MultiChain, a permissioned blockchain platform based on the Bitcoin protocol, primarily leveraging stream-based data handling without native smart contract support. To enable a comparative evaluation, we developed a replicated version of the proposed system using Solidity smart contracts deployed on an Ethereum-compatible network. For this purpose, we utilized the Web3.py [98] library in Python, which offers a robust interface for interacting with Ethereum nodes via JSON-RPC. The smart contracts were compiled using the Solc compiler and deployed to a local blockchain environment, such as Ganache. Web3.py enabled us to invoke contract functions, send transactions, and monitor emitted events directly through Python, facilitating detailed interaction and automation. This comparative setup allowed us to analyze the behavioral and performance differences between the original MultiChain-based implementation and our Solidity-enabled replicated version.

6.2. Testbed Schema

The existing framework relies on the computational capabilities of two essential components within the SDIoT architecture: the MultiChain blockchain platform and the SDN controller. It is important to note that MultiChain is a private (permissioned) blockchain, whereas the comparative blockchain used in our replication is a public Ethereum-compatible blockchain. This distinction allows for a comparative evaluation of privacy, performance, and flexibility across different blockchain infrastructures within smart city environments. These components play integral roles in enabling seamless and secure message transmission between diverse services, ensuring effective interoperability. The MultiChain and Ethereum blockchain platform functions as a tamper-resistant ledger, facilitating secure data exchange and communication across various smart services. Its computational efficiency directly influences the speed and reliability of transaction validation and smart contract execution for seamless interoperable smart services in smart cities for collaborative tasks [99]. Likewise, the SDN controller, a core element of the SDIoT architecture, manages network infrastructure and traffic flows. Its computational prowess significantly impacts network allocation and management efficiency. A dynamic and resilient SDN controller optimizes message flow among services, minimizing latency and guaranteeing timely data transmission [100].

To evaluate the performance of the proposed security framework due to the integration of the Ethereum and MultiChain blockchain platform with SDIoT architectures, we selected the following performance evaluation matrix from existing security governance solutions. The performance evaluation matrix is an essential tool to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of security governance solutions. It provides a comprehensive overview of key performance indicators (KPIs) that are used to measure the performance of security solutions.

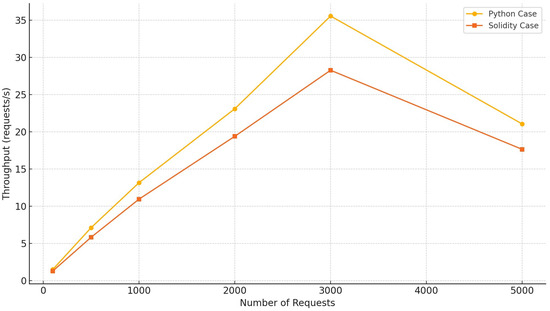

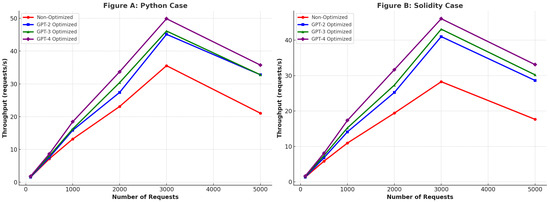

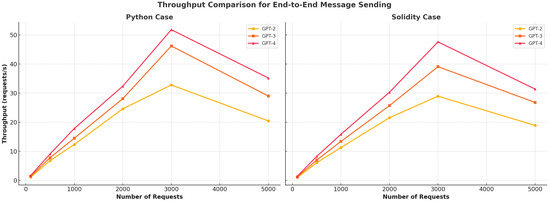

- Throughput/sec: Throughput per second is a metric that quantifies a system’s capability to handle a specific quantity of requests within a one-second interval. In the context of our existing framework, we aim to evaluate the combined throughput of the SDIoT and blockchain components with both optimized and non-optimized smart contract execution. This evaluation involves assessing the number of requests sent from IoT client nodes to the adaptive engines, which facilitate the connection between the local and global blockchains via a client–server architecture. A high throughput per second indicates the capacity of the SDIoT and blockchain components within the proposed security framework to efficiently handle a substantial volume of requests in a short period of time. This leads to improved response times. On the other hand, a lower rate of data processing per unit of time may lead to delays in service delivery and extended response times.

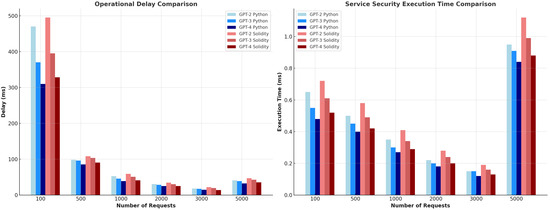

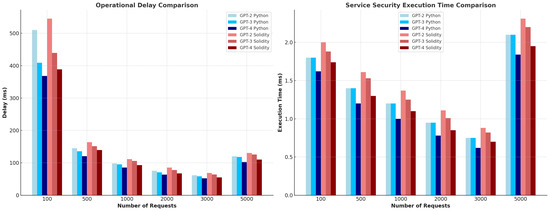

- Execution of Smart Contract/ms: Optimized and non-optimized smart contract execution per millisecond (ms) has a direct impact on the responsiveness and effectiveness of blockchain-based applications. A high smart contract execution speed indicates that the system can process and execute a large number of smart contracts in a short amount of time, allowing for quicker transaction confirmations and an enhanced user experience. On the other hand, a slow smart contract execution speed can result in delays in transaction processing, longer confirmation times, and potential bottlenecks in the system.

- Operational Delay/ms: Operational delay, measured in milliseconds (ms), represents the time needed to process a request originating from the global blockchain. This request traverses the local blockchain and subsequently reaches the SDN controller of the interoperable service for the verification of the request’s legitimacy. This assessment parameter holds significant importance in understanding the interaction between the client–server components spanning across the local and global blockchains in both optimized and non-optimized smart contracts.

The testbed we have designed prioritizes two essential processes involved in collaborative message flow, which are crucial for ensuring the interoperability of services in smart cities. These processes include

- Fetching Smart Contracts from Global Blockchain to Local Blockchain: The global blockchain is responsible for storing the contracts of administrative nodes to enforce security rules for smart service applications. Meanwhile, the local blockchain functions as an administrative node, responsible for executing services and ensuring compliance with predefined security policies.

- Sending and Receiving Encrypted Messages Between Interoperable Services: This process ensures secure communication across different interoperable services, maintaining data integrity, confidentiality, and authentication in smart city environments.

The investigation is conducted by evaluating these two workflows while executing optimized and non-optimized smart contracts fetched from the blockchain. In the experiment, we gradually increase the number of collaborative service request messages while keeping the number of IoT client nodes constant. The message-sending rates are also incrementally increased at 600 ms, 120 ms, 60 ms, 30 ms, 15 ms, and 5 ms intervals. We implemented the testbed using four physical machines, out of which three machines function as smart interoperable services while the fourth machine serves as the blockchain server, responsible for enforcing security governance on the connected services. The configuration details of each machine are provided in Table 10, which outlines the specifications and settings of the hardware used.

Table 10.

Hardware configurations of the four physical machines.

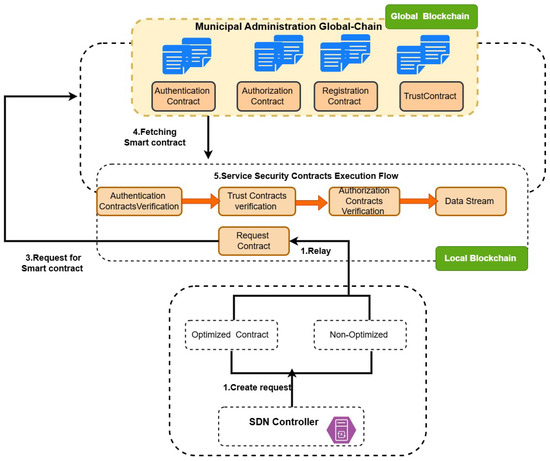

7. Experiment 1: General Workflow of Fetching Smart Contracts from Global Blockchain

The general process of setting up the system starts with obtaining the smart contract from the global blockchain to the local blockchain, as shown in Figure 7. In the base paper, the global blockchain functions as a decentralized distributed administrative node, and the local blockchain of the same platform functions as a decentralized distributed application called DApps. In our Ethereum-based replication, we simulate the global and local blockchains by defining two separate wallet addresses, effectively representing distinct administrative and decentralized application layers within the same network. A decentralized application (DApp) functions as the local blockchain, in charge of running commands through smart contracts retrieved from the global blockchain. This fetching process ensures that either an optimized or non-optimized smart contract is securely transferred from the global blockchain to the local blockchain, enabling seamless execution of interoperable services in smart city environments. The following are the general steps used in the workflow of fetching both smart contracts (optimized and non-optimized) from the global blockchain to the local blockchain for both Python and Solidity cases.

Figure 7.

Smart contract fetching.

- In the first step, SDN controller creates the request to fetch the optimized and non-optimized smart contracts from the global blockchain for both Python and Solidity cases by encrypting the request message with the public key of the local blockchain and signing the message with its secret key, as shown in Equation (6).

- In the second step, this request is forwarded to the module request contract. This module is responsible for verifying the received message by decrypting the message with its private key of the local blockchain and verifying the signature of the SDN controller, as shown Equation (7).After decrypting the message, it signs the message again with its private key and encrypts the message with the public key of the global blockchain, as shown Equation (8), and forwards the fetch request of smart contract to the global blockchain.

- In the next steps, the received request message is first decrypted from the private key of the global blockchain, the signature of the private key of the local blockchain is verified, and then the contract is forwarded to the local blockchain by embedding the security features in the message, as shown in the Equation (9).

- In the final step, the local blockchain decrypts the received smart contract using its private key and verifies the global blockchain’s signature. Once verified, the retrieved smart contract is updated in the local blockchain datastream through transaction, also called smart contract execution process.

7.1. Result Discussion of Non-Optimized Smart Contract Fetching

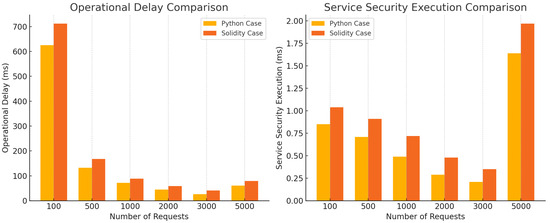

The performance metrics for fetching non-optimized smart contracts from the global blockchain measured in terms of throughput, operational delay, and service security execution time for both the Python and Solidity cases are presented in Table 11 and Table 12, respectively.

Table 11.

Fetching non-optimized smart contracts from global blockchain in Python case.

Table 12.

Fetching non-optimized smart contracts from global blockchain in Solidity case.