Highlights

- Develop an approach that enables digital sovereignty while providing innovative mobility services and applications to citizens.

- Explore how to maintain digital sovereignty to improve urban mobility services in local communities.

What are the main findings?

- Propose a policy framework to improve sovereign data usage control for citizens.

- Support business operations for mobility service providers and also increase data autonomy, trust, and transparency for citizens.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Based on grounded theory and a literature review, this study explores the factors that influence digital sovereignty from local communities’ point of view.

Abstract

Achieving a climate neutral economy by 2050 in Europe in line with the European Green Deal places specific responsibility on the transportation sector, which contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For the transportation domain to reduce its GHG emissions, there is need to advance urban mobility solutions in local communities via the use of data in all modes of transportation. Accordingly, to intelligently improve mobility solutions, huge amounts of data are needed from citizens in local communities to improve mobility services. However, the access, usage, and ownership of data in the transportation sector continue to be hindered due to issues including privacy, security, and trust concerns, among others. However, to improve smarter mobility solutions, there is a need for clarification of digital sovereignty, which today hinders data flow among different actors in the transportation sector. Therefore, research is needed to provide an approach that enables digital sovereignty while providing innovative mobility services and applications to citizens. Accordingly, this article carried out a systematic review to explore how to maintain digital sovereignty to improve urban mobility services in local communities. Based on grounded theory and a literature review, this study explores the factors that influence digital sovereignty from local communities’ point of view. More importantly, a policy framework is proposed to improve sovereign data usage control for citizens. Additionally, recommendations for achieving digital sovereignty are presented to foster data ecosystem business opportunities for mobility service providers and to increase data autonomy, trust, and transparency for citizens.

1. Introduction

Transforming European cities and communities into a climate neutral economy by 2050 in accordance with the European Green Deal places responsibility on the transportation sector, which contributes to a quarter of the European Union (EU)’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. For local communities to become a democratic digital society that serves the interest of citizens, it is necessary to push towards a zero-carbon society to address climate changes [2]. Specifically, there is a need to collectively minimize GHG emissions from the transportation sector via the use of data in all modes of transportation, both in passenger and freight transportation [3]. With the provision of data-driven mobility services in local communities, data have become an economic commodity that have also led to novel data ecosystems [4]. Thus, in providing data-driven mobility services to citizens, data are usually collected from individuals who have no ownership or personal control over their data, limiting their autonomy. According to the European Commission (EC), Europe must now improve its digital sovereignty by initiating policies and setting standards with a clear focus on technology, data, and infrastructure [5]. Thus, it is necessary to have access and usage control to protect citizens’ digital assets through usage control strategies. Thus, the concept of digital sovereignty is important [6].

Nevertheless, data availability, ownership, access, and sharing in the transportation sector today have continued to be hindered due to different standards, unclear regulatory policies, lack of data usage control, and digital sovereignty concerns, among others [7]. Digital sovereignty provides the needed control and transparency and the greatest levels of security and privacy that are needed to fully exploit the potential of available data and control over virtual assets [8]. Thus, digital sovereignty not only involves citizens having control over the usage and design of digital systems and the data produced and stored therein; it also allows for citizens on the individual level to regain control and ownership over their own data [6]. Digital sovereignty raises users’ awareness regarding digital technology and how their data are used [9]. In Europe, policies like the “European strategy for data” exist, which intends to achieve a single market for data [10] where data can be accessed and efficiently used. This also includes the development of a common European mobility data space that facilitates pooling, access, and sharing of mobility and transportation data [7,11]. While mobility and transportation companies recognize that data are valuable for optimizing their business processes, the availability of data to be used by these companies is minimal because data owners/data producers (citizens) fear losing control over their personal data [8]. This has, in turn, resulted in a reduced willingness of citizens to participate in sharing their data.

Thus, legal policies, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), were introduced in Europe to govern the use of personal data of EU citizens, but they have not been sufficient to address data usage control, access, and ownership issues [4]. Also, current data ecosystem initiatives do not give data owners/data producers assurance that their shared data are used as intended [12]. Moreover, in local communities, data sovereignty needs to be maintained to promote trusted data sharing towards achieving a secure data-driven service, such as a smarter mobility solution. In this context, consideration must be dedicated to improving approaches to data usage control standards, access, and ownership of citizens’ data by organizations while ensuring ethical and fair participation of citizens regarding the authorized processing of their data [6,13]. This will give citizens the ability to own and control the flows of their private data, as this is one of the underlying principles of self-sovereign use of data to improve public transportation in local communities [2,14]. Thus, this paper aims to investigate the following research questions.

- How can we empower citizens’ sovereign control over their data, enabling granular access control and thereby facilitating the sharing of data only with explicit consent?

- What factors influence self-sovereign sharing of citizens’ data to improve urban mobility solutions in local communities?

Presently, the availability, accessibility, and sharing of data within the transport and mobility sector, as well as the unclear regulatory conditions for data exchange within this sector, have continued to hinder the development of seamless, connected, and interoperable mobility services. Accordingly, the main contribution of this study is to explore how to maintain digital sovereignty to improve urban mobility services in local communities rooted in the citizens’ perspective. Findings from this study will impact key transport mobility, as data have been identified as a valuable input to boost the development of digital twins to be used by NRAs, road operators, and other stakeholders. Key findings from this study will impact transport mobility by exploring how to achieve self-sovereign data collection and sharing to boost the development of digital mobility services to be used by different stakeholders, such as mobility service providers, citizens, road operators, national road operators, and others.

In this way, this study contributes by identifying the factors that influence digital sovereignty from local communities’ point of view. Also, this study proposes a policy framework to improve sovereign data usage control for citizens by depicting directions for further exploration in the area of digital sovereignty. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. First, the theoretical background is presented in Section 2 and Section 3, the methodology is discussed, and Section 4 presents the findings. Section 5 presents the discussion and implications of the study. In Section 6, the conclusion is presented.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Overview of Digital Sovereignty in Europe

In a bid for nations to protect their citizens’ rights in the digital sphere, discussions around digital sovereignty have emerged [15]. Additionally, with digitalization enabled by data that transcend geopolitics and economics, nations will need to reaffirm their authority to protect their citizens and industries. This has necessitated the need for digital sovereignty [6], where sovereignty refers to the power of an entity to govern itself [9]. On a national level, the term digital sovereignty has been used by the government to convey the idea that states should have authority over the internet to protect their citizens and companies to control the data of their people and the digital infrastructure in their territories [6]. Thus, for about two decades, countries across the world have started to adopt digital sovereignty as a means to address issues linked to digital foreign interference by big foreign tech platforms and infrastructures and state actors and reliance on foreign governments, thereby “democratizing” the notion of sovereignty across the digital domain [16]. The EU has now recognized the importance of retaining self-sovereignty; as such, the EC has redirected its efforts into adopting comprehensive regulation across the technology sector to uphold Europe’s digital sovereignty [6].

Accordingly, a recent study from the European Parliament highlighted that the dominance of foreign corporations that provide internet services in the EU may result in the loss of European sovereignty [3]. This is because these large corporations, mostly non-EU-based, are progressively seen as leading most sectors of the EU economy, thereby limiting EU member states of their sovereignty in areas like data protection, copyright, ownership, etc. Moreover, governments in the EU, particularly Germany, have stated their intention to initiate digital sovereignty as part of European digital policy. This move contributes to reasserting the government’s authority over cyberspace to protect their citizens and companies from the limitations of not having control of their data [6]. Accordingly, the EC aims to ensure that European data will be utilized by companies in Europe to create value for Europe [3]. Also, in 2020, the EC initiated the European vision of digital sovereignty to balance the dissemination and use of data while preserving ethical standards, privacy, security, and safety [8]. In the digital sphere, several risks arise that can challenge digital sovereignty, such as inadequate control over digital assets, applications, and systems where data reside, and citizens inevitably face threats to their data [17].

This is supported by findings from a recent report that mentioned that the EU is ever more aware that although digitalization contributes to society, it is associated with a number of challenges, such as the digital divide, cyber-attacks, data privacy, and the concentration of autonomy in a handful of tech companies [5]. As such, digital sovereignty has become a prominent feature in EU policies [1]. While the notion of sovereignty is mostly centered around the control, transfer, and storage of data, the concept of digital sovereignty remains rather abstract in some sectors of society, such as in health, energy, transportation, etc. [1]. In local communities, there have been issues relating to citizens’ digital rights and how data about citizens are collected by different actors, for what purpose, and how the collected data are accessed, saved, shared, and reused to provide data-driven services [18]. Thus, citizens would like to have authority and control over their data and their usage [6]. Digital sovereignty can be seen as a geopolitical necessity that opposes both foreign corporations and foreign governments, allowing the government to give back power to their citizens by protecting the rights of citizens in the digital sphere. This often takes the form of regulating foreign companies that mediate data flows for local communities [3].

2.2. Digital Sovereignty in Local Communities

The digitalization of society is driven by the availability of data that are either created by citizens or generated by systems/sensors. For example, this includes geospatial information, data from an On-Board Unit (OBU) of a car, camera data, weather data, etc. But, the use and sharing of these data are challenging due to irresponsible and malicious use, leading to privacy and security breaches. Thus, it is necessary to properly set up digital sovereignty policies within society, including how to share autonomous control and decision making about digital assets exploited within mobility service platforms used by citizens by specifying responsibilities around assigning, defining, and allocating data usage.

Presently, personally identifiable data generated from citizens in local communities are saved in cloud services located across different geographic locations, which are governed under different laws, policies, etc. This has resulted in self-sovereignty challenges as data are increasingly distributed and shared across borders [19] by big tech companies, such as Facebook, Google, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, etc. [2], which are collecting and processing large amounts of data from their customers. This has resulted in the emergence of power imbalances with severe effects on individuals and businesses in Europe and other regions in the world. To enable data owners and data producers to share their data, it is necessary to give control over the usage of data from third parties to data owners and data producers throughout the usage cycle of data [20]. This is because when using cloud infrastructure, most citizens do not exactly know where their data are hosted, i.e., which data centers or country clouds are used to store the data [21]. In business contexts, digital sovereignty is typically managed in big tech companies as a part of the Service Level Agreement (SLA) management system [21]. These big tech companies are in a distinctive position to collect, save, and analyze data harvested through the online activity of citizens when using their platforms, most of the time without users’ knowledge and approval.

This highlights why digital sovereignty is important at an individual level, as the data owner/data producers need to be able to exercise their usage control, rights, and autonomy for self-determining whether they want to participate in sharing data [17,20]. The actualization of data usage control as a practical operation of digital sovereignty is a barrier but nonetheless a necessity [22]. Digital sovereignty underlines the importance of individual self-determination, with a focus on the autonomy of citizens in relation to their roles as users of digital services and technologies to be able to govern who gets access to and utilizes their data and digital assets. Digital sovereignty can also be perceived as the ability of individuals to take action and make decisions independently over the handling and access of their data [17]. Moreover, digital sovereignty related to data usage control is a multi-faceted and complex aspect experienced across data sharing infrastructure, and, as such, it is difficult to enforce in data ecosystems. Research is needed to enhance the design of data infrastructure that can contribute to the development and implementation of digital sovereignty in local communities [17].

Due to the lack of attention paid to data rights and the small number of initiatives centered on implementing data ownership and access mechanisms deployed to support data owners/data producers to exercise control over their data [20], there is a need to improve the availability of data for the benefit of society by fostering data sharing services and infrastructure that provide contractual agreements based on fair regulations and incentives to data owners/data providers [7,23]. Generally, issues related to data management, access control, ownership, governance, and storage are typically referred to database administrators and technicians [24]. Hence, research is needed to explore data usage control needs motivated by citizens’ requirements [25]. Following this, it is required to describe and clearly specify what constitutes access control, which encompasses utilization control, to enable data owners and data producers to continuously monitor and orchestrate the usage of digital assets, such as files, datasets, or services [22].

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method and Procedures

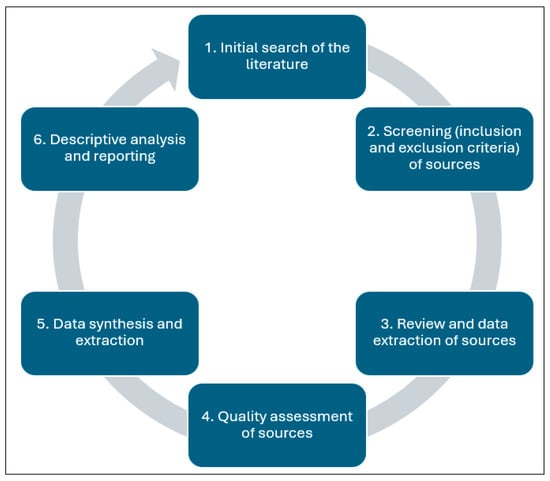

This study adopts a systematic review of the literature based on the guidelines from Kitchenham [26] and the recommendations from Webster and Watson [27], as shown in Figure 1. In the first phase, “the initial search of the literature,” online databases and search engines were used for searching the literature. The online databases and search engines comprise Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. To carry out the search, several keywords were used, including “self-sovereignty” OR “digital sovereignty” OR “data sovereignty” AND “smart mobility” OR “intelligent mobility” AND “local communities.” Because digital sovereignty is an emerging topic, the search period was restricted to research published between 2000 and 2025. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated to efficiently select relevant sources that are aligned to the study area of how digital sovereignty can improve smarter mobility solutions in local communities. In this study, the inclusion criteria were restricted to studies that are more aligned with the research questions being explored, as presented in the introduction section of this paper. The exclusion criteria help remove studies that are not aligned to the study area.

Figure 1.

Sources search process flow diagram.

Overall, sources are included if the paper elaborates on digital sovereignty and specifically provides comprehensive explanations of how to support citizens to address sovereign access control over their data, thus enabling the sharing of their data. Sources that investigated factors that influence how self-sovereignty of citizens in sharing data can help improve urban mobility solutions in local communities are also included. Sources that are based on surveys, reviews, and case studies that identify open challenges and future research trends objectively related to digital sovereignty are also included. Sources published in the English language with scientific methods that are well-specified are included. Journal articles, conference proceedings, technical reports, book chapters, and dissertations are included. Other sources not conforming to these criteria are excluded from this review.

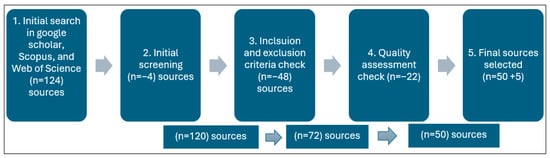

Figure 2 shows the literature selection process employed to select sources related to the study area of digital sovereignty. Based on the initial searched sources (as shown in Figure 2), 124 potential sources were retrieved from the searched online databases using the keywords previously stated. After initial screening, 4 sources were removed as duplicates, and the 120 sources were then checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (as previously stated). Then, 48 sources were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. This resulted in 72 sources, which were checked for quality assessment. For the quality assessment, this study evaluated each of the sources included by checking the methodological contribution of each source, highlighting if the source is highly relevant to the study area and if there is a clear methodology or approach that was employed in the study to address the aim and research objectives.

Figure 2.

Sources selection process.

Moreover, to further assess the quality of the sources, the presentation of the findings or the results and the availability of discussions on future directions were checked, as suggested in the literature [17]. Subsequently, 22 sources were removed due to the sources being of low quality. This resulted in 50 sources included for this study to explore how digital sovereignty can improve smarter mobility solutions in local communities, with 2 sources including literature reviews [26,27]. The final 5 sources included are in the reference section of this article, resulting in a total of 55 sources. Next, qualitative data were extracted and synthesized from all sources to collect the information needed to answer the research questions being explored, as shown in the introduction section of this paper. Lastly, descriptive analysis was employed to present the findings from the literature.

3.2. Grounded Theory Approach

Grounded theory is a typical methodology employed to systematically conceptualize a theory based on data [28]. Grounded theory is originally rooted in social research based on initial concepts proposed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, which was published in 1967 [28]. Since then, grounded theory has been adapted and adopted over time. The earlier method is frequently referred to as standard grounded theory, alongside constructivist grounded theory by Kathy Charmaz [29] and interpretive grounded theory by Juliet Corbin and Anselm Strauss [30]. In this study, the factors that influence self-sovereignty and sharing of citizens’ data to improve urban mobility solutions in local communities are conceptualized into a policy framework based on grounded theory, as seen in Section 4.6.

4. Findings

Based on the systematic literature review, this section descriptively presents the findings from the analyzed sources by extracting qualitative information concerning the research questions being examined.

4.1. Digital Sovereignty from Political Levels to Societal Context

Citizens are concerned about losing control of their personal data, and this has limited them in sharing their data, which is useful for creating novel business models, especially in sectors like transportation. Thus, it is not easy to change the mindset of citizens to open up their data for sharing and collaborative purposes [17]. Moreover, to enable citizens to have meaningful and effective ownership or control over their personal data, which is being used by third parties through data analytics for value creation [17,31], digital sovereignty is deemed important and commonly employed by governments to capture the idea that states should reaffirm their autonomy over the internet and protect residents and businesses from the diverse issues posed by digitalization.

Likewise, digital sovereignty concerns are now ever-increasing due to increased reliance on cloud-based services and remote data storage, which face issues related to territorial ownership claims and data privacy [32]. Digital sovereignty addresses other important digital issues, including data protection, national security, competition, and content regulation [31]. Digital sovereignty is not just about data ownership, where the data’s owner has the right to use the data how they see fit without the control of a technology service provider [24]. Individuals should be able to dictate how their data will be collected and used within a specified domain to provide digital services to society [24,33].

Accordingly, the concept of sovereignty in relation to digitalization has gradually become an area of increased public policy concern, as data are now an essential element of the digital economy [17,31]. Digital sovereignty is the ability to have control over data, digital infrastructure, and technological capabilities [1]. It also considers how and where the data are stored (the storage locations of the data), specifically, how long it is kept for, who will have access to the data in the future, etc. [24]. But, digital sovereignty is challenging to achieve in most countries, as the servers of most standard cloud services are not physically situated in the country that has ownership of the data. Also, there are no assurances that citizens’ personal data will never leave the country of origin [24]. Hence, there is considerable tension globally over the nature and extent of business and external government control over citizens’ data. Governments across the world are now starting to enforce national polices to address the issues of digital and data governance towards exercising self-sovereignty over data [17].

In the EU, this has prompted the adoption of new legislation, such as the digital services act, the AI act, the digital markets act, etc. [1,24], by EC to address issues related to cross-border movement, which controls the territoriality of citizens’ data [1]. As such, cloud service providers, such as Google, have begun initiatives that support digital sovereignty by adhering to EC data policies aimed at enabling Europe’s businesses and establishments to exercise total autonomy over their data [17]. Therefore, many countries are now introducing policies or laws to maintain their control over data, in some instances insisting that data be retained within their national borders. In this case, control over data is directly linked to national digital sovereignty. To address sovereignty issues, some European countries, such as Estonia, are storing important state data in a secure data center situated in a friendly country. As digital sovereignty is associated with data localization laws, they typically demand that sensitive personal data are saved within state boundaries to address the data protection concerns of citizens [19]. Furthermore, some countries are concerned about their ability to utilize their own data to develop regional innovation-based businesses, leading to policies that restrict the external flow of certain types of data. As such, evidence from the literature maintains that certain categories of national data should be the focus of specialized national economic development initiatives in order to serve domestic markets [19].

4.2. Relevant Institutional Data Polices Related to Digital Sovereignty in Europe

Across European countries, the treatment and use of citizen data have been administered by strict legal regulation and policies, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), stipulated by the EC to protect the privacy of individuals during the processing and exchanging of residents’ personal data. Although citizens should be enabled or given autonomy to control how their data are stored or moved [21], to achieve digital sovereignty, big tech companies deploy geo-location rules when (re)locating data within their cloud infrastructures for authenticating the compliance of SLA policies when storing citizens’ data. Nevertheless, no assurance is provided to citizens that their data cannot be duplicated, copied, or moved to other locations [21]. As such, citizens who are data producers or data owners have to trust that these companies are doing the right thing ethically related to their data. But, at times, this has resulted in data stored in clouds being exposed to potential insider exploitation [21]. As such, two policies (the data governance act and the EU strategy for data) have been initiated as essential cornerstones of this development to support self-sovereignty of citizens’ data [25].

4.2.1. The EU Data Strategy

The EC has put forward significant indicators for developing the single market into a digital market, thereby promoting data-driven communities and cities by empowering citizens, institutions, and organizations to make decisions based on information derived from non-private data [34]. The EC aims for non-personal data to be available to all to create a data-agile economy. To achieve this ambition, the EC proposed the EU Data Strategy in February 2020 as a basis to guide existing and upcoming data regulation across the EU. The objectives of the EU Data Strategy involve (1) achieving the seamless transfer of data across the EU and within sectors; (2) initiating adherence and respect for European values and rules, specifically, private data protection, end user protection, and business competition law; and, lastly, (3) promoting fair, clear, and practical guidelines for sharing and use of data based on reliable data governance mechanisms [34]. Overall, the focus of the EU Strategy for Data is to create a single market for data to be exchanged and shared across sectors securely and efficiently within the EU. The EU Strategy for Data enforces the European data economy based on European values of privacy, self-determination, security, transparency, and fair competition [25,35].

4.2.2. Data Governance Act

The Data Governance Act, proposed on 30th May 2022, provides a foundation for the EU Data Strategy to facilitate the European Data Act to promote data sharing among industries and across companies and governments [34]. Its main areas of regulation encompass (1) making public sector data accessible for re-use in conditions where such data are subject to the digital rights of others (such as IP rights, privacy rights, trade secrets, or other commercial private information); (2) exchanging data among industries, without compensation in any format; (3) enabling private data to be utilized with the help of a private data sharing intermediate that protects data subjects’ rights based on GDPR; and (4) permitting data usage on altruistic bases [34]. The Data Governance Act complements the Open Data Directive, which aims to promote data sharing by strengthening trust in data intermediaries, which are required to play a substantial role in data spaces. The Data Governance Act specifies that data should be findable, accessible, interoperable, and re-usable.

Overall, the Data Governance Act highlights the obligations for data providers (as data intermediaries) to actualize a European model for data sharing of private and non-private data through these neutral data mediators, which can be seen as an alternative to the current prevalence and market autonomy of integrated technology platforms that are operated by corporate businesses [25,36]. From an institutional point of view, the Data Governance Act shall manage the national procedures and policies needed to facilitate cross-sector data usage in the European Interoperability Framework to promote harmonization with European or international data standard; as such, intermediaries may not utilize data received for other intentions than those of the data consumer. Also, the meta-data collected from the data owners or data producers should be utilized to develop several planned services, ensuring transparent, fair, and equitable access to the service for data owners and data consumers with respect to the pricing scheme [36].

Additionally, the Data Governance Act will facilitate exchanging data in formats that the intermediary receives and further governs the conversion of data into different formats that ensure interoperability across and within sectors or when specifically requested by data consumers or if required by law. It also helps to prevent abusive or fraudulent practices, ensuring the continuity of data-driven services [36]. By providing adequate legal, technical, and institutional measures to limit illegitimate access to or transfer of non-personal data, this provides a high degree of security for the transmission and storage of non-private data. Moreover, the Data Governance Act will maintain procedures needed to ensure competition as well as compliance with laws across the EU and member states by guiding data subjects on standard terms and conditions that regulate the potential use of data. This will help with informing the applicable control of data processing where an intermediary offers tools for obtaining permissions or consent from data owners to process their data [36].

4.3. Digital Sovereignty for Self-Sovereignty in Local Communities

The adoption of digital platforms and infrastructure in local communities facilitates the production, processing, dissemination, storage, and use of data about citizens’ lives. These data are generated from cloud infrastructure, physical devices, such as smart sensors, cameras, metering devices, etc. deployed in the urban environment [37]. Currently, personal data, such as passenger movements generated by vehicles or mobile devices, are being gathered and managed by public transportation providers, mobility fleet operators, navigation service providers, and mobile communications providers [38]. For instance, physical devices, such as mobile devices and IP-based CCTVs owned by citizens connected to the appropriate platforms in local communities, can collect data about urban traffic conditions, weather conditions, etc. in real time. Similarly, data collected from citizens can be used to create mobility-related services for third parties, such as the application Waze, which uses crowd sourcing data from citizens and open data to provide in-vehicle route navigation [20]. The collected data can then be processed and used to provide up-to-date, near real-time information for smarter mobility services to other citizens to optimize traffic flows and increase safety [38].

Additional intelligent mobility services may include providing alternative travel route(s) for commuters or information that can be utilized by communal council administrators to make informed decisions relating to public transportation management [21]. Furthermore, smarter mobility solutions can only be fully developed when large amounts of data are made available [7]. For example, citizens’ mobility-related data can provide valuable insights into travel patterns, which in turn can help contribute to sustainable urban planning and the provision of public transportation services. In public transportation, such as rail, the availability of large volumes of data is the basis for efficiency, more capacity, and punctuality in railway traffic. Hence, the use of data can support mobility service providers to achieve substantial savings and improved attractiveness [7].

The data being collected and utilized by public transportation companies that enable the provision of smarter mobility services are often linked to personal information, while citizens seek to control data access levels and disclosure of their details. Individuals, being the data producers and data owners, should possess self-sovereignty to control and authorize the access and usage of their data [17]. However, achieving self-sovereignty, as well as maintaining community control and ownership over data and technological infrastructure, are still inadequate [22,37,39]. This is because existing platforms do not support digital rights management or personal information management to enable individuals to self-determine the usage and access control of their personal data by third parties [39].

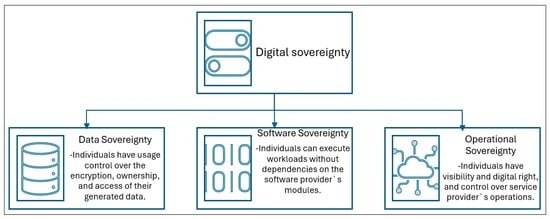

Taxonomies of Digital Sovereignty

According to the literature [40], digital sovereignty comprises three main pillars, including operational sovereignty, software sovereignty, and data sovereignty, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Taxonomies of digital sovereignty.

Figure 3 depicts the pillars or taxonomies of digital sovereignty that are to be considered in achieving the self-sovereign data ecosystem needed for the digitalization of data-driven economies.

- Software sovereignty involves the ability of individuals to be able to manage unexpected events that necessitate them to momentarily change where their capabilities are deployed, and it also involves to what extent external connections are allowed to have access to workloads via open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and services. In summary, software sovereignty enables control, such as in platforms that enable individuals to manage services across different providers and orchestration tooling environments that support individuals to deploy APIs that can be connected to platforms running on different software providers, comprising open-source alternatives and proprietary cloud-based [40]. The need to control the accessibility of workloads (applications running) and to execute software modules with autonomy wherever an individual wants without being reliant on or locked into particular software as a service (cloud provider) has progressively increased. In the context of this study, a workload is usually any application or program that runs on a computer. It can be seen as any capability or service that utilizes cloud-based resources.

- Operational Sovereignty is based on the sector that a citizen functions in, as there might be a requirement for further control of the technologies deployed to provide services. With these possibilities, the citizens can benefit from different degrees of functionality across the digital sphere while maintaining control similar to that enjoyed in a traditional physical environment. Examples of these control mechanisms include constraining the implementation of new resources to detailed service providers in some regions and restraining user access based on predefined features, such as limiting operations based on a geographic location [40].

- Data sovereignty is concerned with the legal assertion that digital information is in line with the rules, regulations, and governance structures of the territory where it is collected, analyzed, processed, and stored. Data sovereignty requires that individuals and organizations exercise total control, supervision, and protection of their data in accordance with the relevant regulatory and legal framework. Researchers, such as Falcão et al. [41], define data sovereignty based on three viewpoints: data usage only with consent, data portability, which involves the prospect of moving data across systems, and transparency regarding the lifecycle of data. Data sovereignty has become a crucial factor that highlights the need to adhere to local privacy, compliance, and security requirements when transferring and handling data across international borders.

- Data sovereignty goes beyond formal institutional structures and involves different modes of governance, involving informal mechanisms that prioritize digital rights and specific cultural contexts [42]. In the context of this study, data sovereignty enables citizens with a mechanism that limits mobility service providers from retrieving their personal data unless citizens plainly approve access for limited providers. Examples of such controls that citizens can initiate include generating, managing, and storing encryption keys in an external location and giving citizens the autonomy to only grant access to their data via these keys to protect data-in-use. These controls allow citizens to be the main arbiters of access to their personal data [40].

4.4. Data Spaces as Enablers of Digital Sovereignty

As previously stated, data sovereignty is often referred to as the ability or right to control data flows and/or govern informational resources. For example, a citizen has usage control over their travel data to be processed by a mobility service platform. Data used by the platform should only be used with the consent of the individual based on restricted access granted by that individual. This aims to promote autonomy and also protect citizens. In a typical data transfer, an individual, business, or system (referred to as a data provider or data owner) shares data with a third party (referred to as a data user or data consumer) and intends to keep control over the data being shared. As such, the “mobility as a service” platform, which generates the data, and the “mobility service provider” storing these data are not the data owners.

Indeed, all mobility information belongs to the citizen, and explicit consent of a user is needed to share the data with third parties. Also, a citizen should be able to track and control how their information is accessed and disseminated [43]. For instance, this might include generated mobility data (e.g., travel patterns) that belong to a citizen (data owner) who can allow access to the mobility service provider (data consumer). Because the data have to be secured, data sovereignty denotes that a data owner can decide and keep control over their data [44]. In most settings, verbal agreements or written contracts are employed, which fail steadily and can be limited with regard to technical solutions, such as data spaces [15].

Thus, there is a need to adopt data spaces as technological mediums that allow citizens as data owners to connect to third parties (i.e., mobility service providers as data users) directly to monitor and control the use of their data. Data spaces are suggested to help citizens in managing data usage control, access, and ownership towards self-sovereignty. Accordingly, the EC acknowledges the significance of data spaces as a constituent of the primary pillar that contributes to the EU Data Strategy [36]. The EC highlights that data spaces address technical and legal barriers faced when individuals and businesses share data by combining the required infrastructures and tools needed to address issues of trust based on common rules and strategies [11,36].

Data spaces include the implementation of data sharing platforms and tools, the design of data governance frameworks, and enhancing the quality, interoperability, and availability of data. The data space strategy proposed by the EC intends to create a “Common European Data Spaces” based on different data spaces, which include green deals, industrial/manufacturing, mobility, financial spaces, health, energy, public spaces, agriculture, skills, and administration [11]. Data spaces also provide access to services using defined interfaces that connect with individual use case scenarios ([40]).

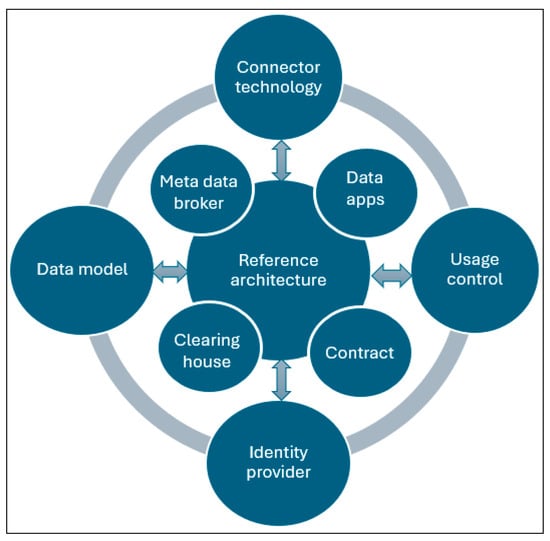

The International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) maintains that data spaces comprise a common framework of reliability and values that include reference architecture, connector technology, certification (clearing house, identity provider), and a data ecosystem that any and all participants and contributors can trust to enable the sharing and exploitation of data within different sectors and applications [36]. According to the IDSA, the key elements of a data space are shown in Figure 4. The connector supports the transfer of data between data owners/data providers and data consumers/data users. This enables the brokering of data via data consumers/data users, who can subscribe to data publications in real time.

Figure 4.

Key elements of data spaces for digital sovereignty.

Thus, connectors enable brokering tasks and also support data apps to combine provided data into datasets in order to enable data transfer in compliance with the usage policy [38]. In addition, the connector can help govern participants’ endpoints to help solve issues of decreasing trust faced by participants (citizens and mobility service providers). This guarantees that only authorized participants can access resources and that defined policies are enforced at all times, notwithstanding the deployment location of resources [40]. Data spaces enable data users, such as mobility service providers, to access citizens’ mobility-related data securely in the connector through “data apps.” These data apps support mobility service providers to integrate data, e.g., from citizen datasets that are saved outside of the connector.

Furthermore, the “data apps.” are hosted in a data app store, which enables easy enrolment and promotion of data apps needed for the administration of mobility-related data [38]. A usage control policy is initiated within the connector that ensures accordance of the data app based on quantified rules specified within the digital contract [38]. Also, usage control policies are checked to ensure that the dataset flows only to the connector that complies with the contract. After this, the dataset provided by citizens is transferred to the mobility service provider [22]. A data marketplace (typically, a metadata directory) supports the publication and presentation of data sources and their conditions of usage. The metadata broker provides metadata in a machine-readable format to enable devices, such as smartphones, automated vehicles, and IoT devices, to be able to find, access, and use them independently. Metadata brokers help in enabling remote search functionalities by providing the required interfaces needed for communicating with any connectors.

More specifically, it can be seen as a discovery service, and it is capable of managing messages from connectors, indicating status updates for individuals, e.g., prompting notifications when new data are available. A data model or semantic hub offers the required domain-specified knowledge about mobility, transport, and traffic data model/data formats (e.g., NeTEx, DATEX II, etc.), as well as APIs (e.g., TRIAS, SIRI, etc.) in the form of ontologies, taxonomies, vocabularies, and models, thus enabling interoperability and data machine readability. In the EU, the DATEX II, a European standard, is commonly used for data exchange; it is primarily used in traffic control centers, as required by law, as a means of exchanging traffic data [38]. An identity provider, which is part of the certification authority, employs identity management operations by serving as a single point of connection that assesses the trustworthiness of actors (data owners, data users, data providers, and data users), as well as datasets and data apps that also enable safe communication.

A clearing house, which is also part of the certification authority, is another entity that is responsible for central logging and recording of transactions carried out across the distributed data ecosystem. The clearing house helps to make data transactions based on contracts made available to the relevant participants to confirm billing for data transfer. The key elements of data spaces support citizens’ (data owners’/data producers’) self-sovereignty in local communities by ensuring that citizens gain ownership and control of mobility-related data collected by mobility service providers to improve their business process data.

Findings from the literature [38] reveal that fleet operators (taxis, car sharing services, public transportation, logistics, etc.), as well as providers of navigation services, are now gathering floating data that capture individual travel patterns. Such types of data are very sensitive, as they contain personal information. Using the data space, citizens can share their data with the mobility service providers via the connector interface. This enables citizens to control how their restricted mobility-related data may be accessed by the mobility service providers and in what state the citizen wants the data to be transferred to the mobility service providers after analyses and processing. In doing so, citizens can offer their data to third parties without the concern of unauthorized data usage for other intents, ensuring that the data are processed in compliance with the citizen’s specifications, as originally intended [45]. This also ensures that the data are exploited according to the licensing and terms and conditions of use specified in the contract, enabling the empowerment of citizens with the possibility to control and monitor the usage of their data [38]. Furthermore, a data app that is verified by a certification authority and is also in compliance with citizens’ requirements is run within the data space. The data app may be developed by a third party and is offered in an app store for providing mobility-related services, such as travel predictions, routing, road conditions, etc. [38]. Thus, data from the citizens can also be used by these data apps, and these data apps can also serve as a potential new data source in the data space to develop an innovative mobility data ecosystem [46].

4.5. Data Usage Control and Access for Digital Sovereignty

Recent developments in the public transportation sector show the importance of data, specifically personal data, generated by citizens. Thus, data can be seen as an economic asset to be utilized in developing novel digital business models (e.g., personalized mobility offers, on-demand mobility services, etc.) towards smarter mobility solutions. Mobility sharing platforms benefit from large amounts of data that are generated, collected, analyzed, processed, and used to improve public transportation in local communities [12]. The data ecosystem typically comprises data providers, data owners, data users, data consumers, and the operator association. The data owner legitimately owns the data to be shared and intends to enforce their digital rights to the data if they are shared to avoid losing control, access, and ownership over their data. A data provider is involved in the data ecosystem and responsible for administering the technical part involved in providing the dataset to be shared on behalf of the data owner. Typically, a citizen can be the data owner as well as a data provider by hosting the digital infrastructure or technology needed to provide their generated data. While, in some situations, the data provider may not legally own the data, they are willing to share and may share the data on behalf of the data owner [12].

Conversely, a data consumer is an actor interested in a dataset who makes requests to receive data from the data provider and eventually sends the data to a data user who then analyzes and processes the data. Also, the role of the data consumer and the data user role can be a single entity [12]. Lastly, the operator association or certification authority (typically, the clearing house, metadata broker, and identity provider) mainly certify all data transactions and also check certifications that the datasets shared are of a certain quality and are called in in case of any disputes [23]. The first basis of data sovereignty is the guaranteed enforcement of trust in usage control [12]. To support the sharing of data among different users within the data space, there is a need to certify how trust can be fostered within the data ecosystem [32]. Thus, there is need for the certification of participants within the data ecosystem to be carried out by the operator association, which guarantees that all collaborating entities involved in data sharing adhere to a common baseline in relation to data, privacy, security, and protection. Accordingly, Table 1 describes the process carried out by data owners/data providers, data consumers/data users, and the certification authority to ensure self-sovereignty of citizens’ data, adapted from [22].

Table 1.

Process flows to ensure self-sovereignty of citizens’ data.

Furthermore, a data space as a data ecosystem is proposed to provide a medium where these actors can interact digitally to support data sovereignty for data owners and data providers when they share data [46]. Possible certification includes defense-in-depth strategies and security event monitoring systems. Other data space initiatives, such as GAIA-X certification, involve identity management, which requires participants to provide a standardized self-description, which is checked before a new contributor is allowed to participate in the data space. In the data ecosystem, this provides a medium for all actors involved to identify each other, thereby establishing a common approach for mutual trust [12].

Data Usage Control and Access Schemes in Data Spaces

In using data spaces, data owners can create access control policies for their data, enabling data owners to enforce usage rules. Nevertheless, data owners implementing access control policies cannot completely ensure data sovereignty, as data ownership is difficult to enforce after data owner or data provider legitimately grant access to data consumer or data user [12]. However, usage control schemes can be deployed to grant specific rights regarding data by enforcing certain policies that must be adhered to when the shared data are being processed by data consumers or data users. For example, one such policy could be permission to use the shared dataset for a certain period of time, with the obligation to delete the dataset after the stipulated period. Furthermore, the IDSA employs an adapted Open Digital Right Language (ODRL), a policy language for managing digital rights that allows for fine-grained design based on usage terms. For compliance execution, the data owner trusts that data consumers usually abide with the negotiated terms stipulated in a contract (e.g., a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) [22]. Also, the data owner does not have credible proof that data usage terms will be adhered to by the consuming party.

Hence, data owners need to trust that data consumers will adhere to the agreed usage policies and not misuse the shared data locally. But, the data owner can be compensated if the consuming party violates any of the negotiated terms, such as, for instance, using the data for other purposes or re-sharing the data with third parties or other systems [12]. Findings from the literature argue that the data of citizens stored on a cloud can still be accessed by an actor who has administration rights, rendering exiting usage control polices initiated by data producers and data owners ineffective. This necessitates the need for more practical data usage control and access measures, which are still lacking in the literature [12]. Access control policies aim to determine which actors, positions, or systems are authorized to access the data provided [47]. Access control can be enforced by providing or restricting data access to explicit users and systems via the procedure of granting authorization to resources via access control mechanisms, such as role-based access control, mandatory access control, discretionary access control, and attribute-based access control [25].

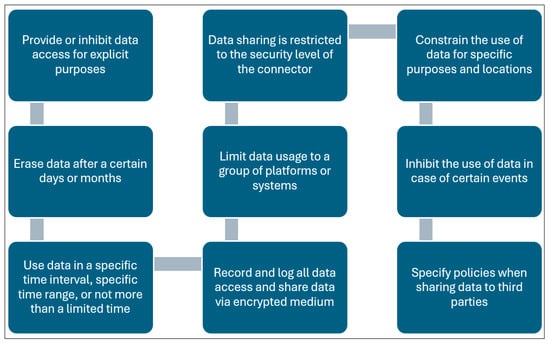

Similarly, sophisticated access control techniques, such as the Open Digital Rights Language employed by the IDSA or the eXtensible Access Control Markup Language (XACML), can be adopted [48]. After data access has been authorized, the next concern related to sovereignty is what happens to the data. Thus, usage control relates to the specification and enforcement of constraints regulating the lifecycle of the data that are shared. Usage control policies assert constraints on how data can be consumed after they have been shared [47]. Usage control is managed with requirements that apply to data processing (responsibilities), such as those related to compliance with regulations, intellectual property protection, and digital rights management. It also involves data provenance (data traceability and tracking) to ascertain the origin or lineage of the shared data [25]. Based on the literature [4,22,25,47], Figure 5 depicts data usage control and access strategies in data spaces.

Figure 5.

Granular usage control and access strategies for digital sovereignty.

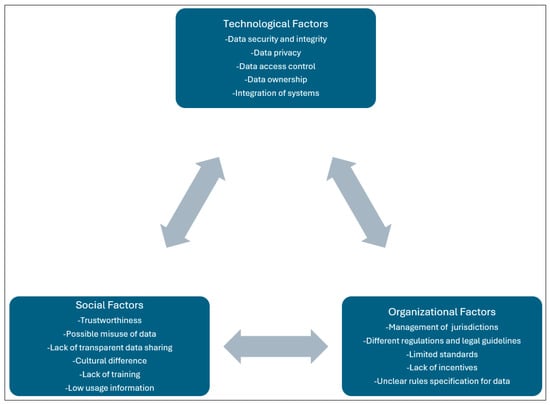

4.6. Developed Policy Framework

As previously discussed in Section 3.2, the factors that influence the digital sovereignty of citizens in sharing data to improve urban mobility solutions in local communities are conceptualized into a policy framework based on grounded theory, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Developed policy framework.

Figure 6 depicts the developed policy framework, which is conceptualized based on the influencing factors governing citizens’ digital sovereignty in data sharing. Each of the factors is discussed below.

4.6.1. Technological Factors

Data security issues are faced in achieving digital sovereignty. This involves issues faced by citizens in preserving privacy of personal information associated with metadata. Thus, stakeholders, such as mobility service providers, road users, road operators, etc., should employ good data security, integrity, and privacy practices to achieve effective digital sovereignty. Hence, there is a need for less complex anonymization approaches that can reinforce data privacy [49]. Therefore, various techniques, as suggested by IDSA and GAIA-X, such as access control (see Figure 5), data encryption, and metadata enrichment, can be employed to improve data security [48]. One such data security, integrity, and privacy measure is to employ proper data separation and classification of data. Moreover, data protection should be deployed with a view to supporting citizens and establishments with practical implementation of technical aspects of data protection, and data protection by default and by design should be adopted to enforce data security protection when data are used and shared by different stakeholders.

Additionally, data security and integrity are crucial to citizens during data transfer, processing, and storage. Ensuring how data are confidentially handled is an important requirement, specifically to ensure that no unauthorized third party can access citizens’ personal information to inhibit potential privacy violations [50]. Moreover, the use of different infrastructures deployed by mobility service providers makes it challenging for citizens to gain ownership of their data. Also, some citizens integrate cloud services where their mobility-related data are stored, while others use different platforms or outdated legacy systems. Likewise, the integration needed for implementing connectors in data spaces based on the citizen platforms being used may not support a trusted environment that maintains digital sovereignty [48].

Moreover, to ensure that citizens’ data are safely used to provide mobility services, additional data security techniques can be employed. These include divide and conquer, obfuscation, Transport Layer Security (TLS)/End-to-End (E2E) encryption, transport layer privacy/source anonymity, secure multiparty computation, pseudonymization, PPRL (privacy-preserving record linkage)/Enhanced Privacy ID (EPID), zero-knowledge proof, (fully) homomorphic encryption, and functional encryption.

4.6.2. Social Factors

Findings from the literature show that transparent data sharing creates trust for citizens. This can be determined, for example, by auditing and verifying saved data access log files. Also, watermarking techniques can be used to partially protect citizens’ generated data by tagging them upon creation or retrieval to enable traceability of the dataset [48]. Cultural sensitivities, comfortability, carelessness, and easiness required in sharing data also influence citizens’ willingness to share their data [24,48]. There is a lack of training to adequately equip data owners with the knowledge to manage their datasets with regard to sharing sensitive and business critical information [51]. Information regarding internal processes and how shared data are handled is not transparently known by data owners. Trust is an issue, as citizens are apprehensive of losing control over their data, and this is inhibiting data sharing [9]. Likewise, there are concerns regarding the possible misuse of data by big companies. Thus, trust is needed so that citizens have confidence that mobility service providers will comply with the legal contractual agreements involved in the processing of their personal data [48].

4.6.3. Organizational Factors

Issues related to the management of jurisdictions, including different regulations and legal guidelines, limited standards that improve data-driven solutions, and the lack of incentives and benefits, limit citizens’ interest in sharing their data [49]. As each citizen is a data owner or data producer, this only defines the right to access, use, or modify their datasets. The signing of legally binding contracts that are accompanied by organizational assurances for citizens as an indispensable requirement for data sharing does not enforce binding obligations over the complete lifecycle of the shared datasets. Also, there are unclear processes regarding technical and non-technical aspects relating to rules and specifications for data processing, continuity, and possible deletion [49].

5. Discussion and Implications of the Study

5.1. Discussion

The use of digital services by citizens has increased over the last decade. These digital services are mostly controlled by a few companies, such as Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, etc. These big tech companies provide technologies and digital platforms; as such, they exercise autonomy over the data as custodians of the data. This has resulted in data privacy issues but also legal issues of data sovereignty [32]. Presently, the concept of sovereignty as it relates to digitalization has gradually gained attention internationally, especially in Europe, due to challenges related to data protection and privacy. As such, individuals and organizations intend to have control over their data and also prevent unintended distribution and usage [15]. However, the effectiveness of data sharing in the data economy is dependent on governance schemes put in place to enforce contractual rights throughout the data ecosystem by utilizing contracts (bilateral one-to-one or multilateral usage through one-to-many) that govern the model deployed for sharing data via different licensing agreements [36]. Digital sovereignty involves control of data flows across a national jurisdiction, empowering individuals and communities in asserting control over their data [42]. The target of digital sovereignty is intrinsically associated with putting the authorized strategies and platforms in the hands of each individual in the data ecosystem, ensuring that data exchange and usage are in compliance with specific and general regulations, extending from the US Patriot Act and the GDPR in Europe to anti-trust and cybersecurity regulations, in addition to sector-specific regulations [32,36].

With the increased use of cloud-based services by individuals, ensuring digital sovereignty is becoming more significant as data are increasingly shared across national borders. Although digital sovereignty requires data to stay within the jurisdiction of origination for territorial ownership purposes, this is most challenging in cloud environments, as data are mostly used by third parties, such as businesses, which use these data to provide data-driven services [32]. Thus, businesses, such as mobility service providers, are now relying on data to improve and develop innovative mobility services [46]. Additionally, these data may be used to control and monitor their internal business operations. At the moment, individuals are willing to share their data, but they are also concerned with available regulations that protect their data privacy and security. This is due to misuse of such data and power imbalances, with service platform providers and individuals not having the option of negotiating data usage terms [41]. Therefore, access to data is important for the public transportation sector. However, the existing legal framework does not clearly outline the legal methods that can be employed to manage data usage control, access, and ownership. As a result, data owners/data producers, such as citizens, are hesitant to provide data to third parties (i.e., mobility service providers as data users/data consumers), and they prefer to have control over and access to their data [20].

Therefore, this study examines digital sovereignty and its practical implementation in urban mobility. Comprehensively, this article shows the importance of trust for digital sovereignty and highlights the need to explore how data spaces can empower citizens with sovereign control over their data, enabling granular access control and facilitating the sharing of their data only with explicit consent. In the literature, the mobility data space was developed by the IDSA [38,52] to support available real-time traffic data (e.g., traffic light sequences, IoT data, etc.) and personal mobility data (e.g., smartphone-generated data, vehicle-produced data, and mobility patterns of citizens). The mobility data space also enables linking local, district, and nationwide data systems to ease the availability of inclusive mobility data on a domestic level [38]. The use of data spaces can support the development of a data ecosystem that can be employed to provide smarter mobility solutions, such as traffic flow optimization, improving multimodal mobility services that contribute to lower environmental impact. Evidently, the use of data spaces is important, as the European data economy is rapidly continuing [25,35]. Data space development is thus significant to value creating for mobility service providers as data users/data consumers through trusted data exchange with citizens as data owners/data producers.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Digital sovereignty is a recent theme that has emerged due to digitalization and advancements in technologies [53], along with the dominance of big tech companies that provide data-driven services to citizens by virtually storing and utilizing cloud services. But, there is need for citizens to regain full control and reassert their autonomy over the collection, storage, processing, and sharing of their data. This also involves citizens being able to determine who gets access to and uses their data on a periodic basis [17]. According to the European Commission [10], private and public (service) providers can benefit immensely from the emerging new data market. Local communities are also part of the data ecosystem, and they also have the capability to contribute to its evolution. For citizens in local communities, the foremost step would be to define and implement the necessary processes for data management to have usage control and ownership that support sovereignty of their data. Presently, academic literature that investigates digital sovereignty in connection with urban mobility in local communities is scarce. Thus, this article aims to explore the notion of digital sovereignty from the lens of citizens and provide an understanding of the technological, social, and organizational factors that influence citizens’ digital sovereignty on a broader level in supporting smarter mobility solutions in local communities.

Therefore, this article systematically examines how to empower citizens with sovereign control over their data by fostering access control and thereby facilitating the sharing of their data with mobility service providers. Findings from this study present a policy framework proposed based on grounded theory and a literature review for maintaining digital sovereignty. The framework supports individuals sharing data in the face of local challenges based on factors that influence the self-sovereignty of citizens in sharing data. In addition, evidence from this study provides recommendations for how to address these challenges that impact individuals’ sovereign control over their data to improve urban mobility solutions in local communities. Findings from this study highlight policies and initiatives deployed especially in Europe to promote policymaking, enforcement, and regulation to limit the technical challenges of achieving self-sovereignty of citizens’ data.

5.3. Practical Implications

In order to reach the goal of a single European transportation market by 2050 [14], the current public transportation system across Europe needs to be further developed into an interoperable and connected transportation solution [54]. As such, access to data is key in the actualization of this goal, but individuals do not have efficient access control and ownership of their mobility-related data. Therefore, it is required to enable individuals to govern the sharing and use of private data across different applications and sectors (i.e., in public transportation) [25]. Accordingly, this study proposes a policy framework that comprehensively covers data usage control, access, and ownership challenges that can arise over the lifecycle of data generated by individuals that can be used by mobility service providers to improve smarter mobility solutions in local communities. This study attempts to contribute to data usage control, access, and ownership issues faced by citizens in data ecosystems by bringing data autonomy back to citizens, especially in the European context within public transportation. Evidence from this study can be used by practitioners to implement granular usage control and access strategies for digital sovereignty in different technological contexts.

Furthermore, insights provided in this study can help to raise awareness of the area of self-sovereign data sharing for citizens and businesses. Findings from this paper contribute to supporting the deployment of data spaces, an enabler for orchestrating data usage control, access, and ownership by reinforcing the practical relevance of digital sovereignty in local communities. The data space is proposed in this study as it offers a data ecosystem in which data owners/data providers (e.g., citizens) can specify the conditions under which their shared data may be used by data consumers and data users, such as mobility service providers and third parties. This supports digital sovereignty by offering a trustworthy environment for citizens, and it gives assurance to users of data regarding the data’s quality and origin. Data spaces can support mobility service providers with citizens’ data that can be utilized to provide smarter mobility solutions, such as real-time traffic management, traffic routing and navigation, on-demand mobility, seamless intermodal trips, first and last mile information, intelligent personal travel assistants, etc. [38].

6. Conclusions

Based on grounded theory and a literature review, this article discusses issues of data usage, control, access, and ownership faced by citizens by examining how to empower citizens with sovereign control over their data, thus enabling granular access control and facilitating the sharing of their data only with explicit consent. The paper also investigated the factors that influence the self-sovereignty of citizens in sharing data to improve urban mobility solutions in local communities. Findings from this study describe a set of key concepts, summarize the current state of the art on digital sovereignty research, and identify various research gaps in the field. Evidence from this study also suggests that there is a distinct lack of research regarding digital sovereignty with respect to urban mobility services in local communities.

To fill this gap in knowledge, a policy framework was developed that links key aspects of factors that influence sovereignty, usage, and control for data owners and data producers, such as citizens. The policy framework provides a systematic description of the key interactions involving these concepts to inform digital sovereignty policies in research and practice. Moreover, qualitative findings identified from secondary data in this study enable trust and transparency for citizens regarding the use of their data by third parties. This study has a few limitations, which is common with most research studies. First, this study employs only secondary data; primary data were not collected as this is a review study. Moreover, the study landscape of digital sovereignty is still evolving in society; as such, there are fewer empirical studies that provide evidence on the study area. Secondly, the developed model was not validated using empirical data collected from different stakeholders. Finally, the study is not aligned with soft infrastructure (digital sovereignty or sovereignty of software platforms) or hard infrastructure, such as physical hardware infrastructure.

However, further investigations will be carried out to study how to adequately encrypt and effectively incorporate data based on “use policy.” Also, as suggested by Del Re [55], the decryption and processing of data in software and hardware infrastructures will be explored based on a designed architecture that governs the “usage policies” and processing of citizens’ data. These will help to re-enforce usage policies for data processing and encryption for stakeholders that use citizens’ data in accordance with the aforementioned “usage policies,” thus ensuring digital sovereignty. Finally, future work will include collecting data using interviews and workshops from domain experts to further evaluate the framework, as well as implementing a data space that enables usage and access control for digital sovereignty for individuals in local communities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This publication is part of the EU MOTIONAL project (MObility managemenT multImodal envirOnment aNd digitAl enabLers) (https://projects.rail-research.europa.eu/eurail-fp1/, accessed on 24 June 2025), WP 31—Federated Dataspace, and the DROIDS project (Digital Road Operator Information and Data Strategy) (https://droids-project.eu/, accessed on 24 June 2025) WP5: Proposing a European data strategy for DROs. The EU MOTIONAL project is under the scope of the Europe’s Rail JU and the EC Framework Programme for Research and Innovation under grant agreement no 101101973, and the DROIDS project is funded by the CEDR (Conference of European Directors of Roads).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jansen, B.; Kadenko, N.; Broeders, D.; van Eeten, M.; Borgolte, K.; Fiebig, T. Pushing boundaries: An empirical view on the digital sovereignty of six governments in the midst of geopolitical tensions. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bria, F. Building Digital Cities from the Ground Up Based Around Data Sovereignty and Participatory Democracy: The Case of Barcelona; Barcelona Centre for International Affairs: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chander, A.; Sun, H. Sovereignty 2.0. Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 2022, 55, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaodong, T.; Shuai, Y.; Ge, H. Comparative Study on Data Sovereignty Guarantee Technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 13th International Symposium on Parallel Architectures, Algorithms and Programming (PAAP), Beijing, China, 25–27 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Niestadt, M.; Reichert, J. The Global Reach of the EU’s Approach to Digital Transformation. EPRS|European Parliamentary Research Service. 2024. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/757632/EPRS_BRI(2024)757632_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Scheider, S.; Lauf, F.; Möller, F.; Otto, B. A Reference System Architecture with Data Sovereignty for Human-Centric Data Ecosystems. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2023, 65, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Pascual, J.J.; Finger, M.; De Abreu Duarte, F.M. Creating a Common European Mobility Data Space; European University Institute: Florence, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Firdausy, D.R.; Silva, P.D.A.; Van Sinderen, M.; Iacob, M.E. Towards a reference enterprise architecture to enforce digital sovereignty in international data spaces. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Amsterdam, Netherlands, 15–17 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Balan, A.; Tan, A.G.; Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P. Data-Driven Intelligent Platforms—Design of Self-Sovereign Data Trust Systems. Land 2023, 12, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. 2015. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0192 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- European Commission. Towards a Common European Data Space. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM (2018) 232 Final, S.1. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0232 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Lohmöller, J.; Pennekamp, J.; Matzutt, R.; Wehrle, K. On the need for strong sovereignty in data ecosystems. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Data Ecosystems (DEco’22), Sydney, Australia, 5 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jnr, B.A. Leveraging Distributed Ledger Technologies for Shared Seamless Electric Mobility-as-a-Service to Im-prove Sustainable Public Transportation in Smart Cities. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockburger, L.; Kokosioulis, G.; Mukkamala, A.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Avital, M. Blockchain-enabled decentralized identity management: The case of self-sovereign identity in public transportation. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmeier, M.; von Scherenberg, F. A Delimitation of Data Sovereignty from Digital and Technological Sovereignty. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2023), Kristiansand, Norway, 11–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jnr, B.A.; Sarshar, S. Enhancing Data Sovereignty to Improve Intelligent Mobility Services in Smart Cities. Urban Gov. 2025, 5, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Chi, C.H.; Lam, K.Y. Analysis of digital sovereignty and identity: From digitization to digitalization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.10069. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, I. Postpandemic technopolitical democracy: Algorithmic nations, data sovereignty, digital rights, and data cooperatives. In Made-to-Measure Future(s) for Democracy? Views from the Basque Atalaia; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.A.; Scassa, T. Who owns the map? Data sovereignty and government spatial data collection, use, and dissemination. Trans. GIS 2023, 27, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ree, B. Data Producers’ Sovereignty an Exploration of Data Rights in Precision Agriculture Initiatives. Master’s Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, C.; Castiglione, A.; Frattini, F.; Cinque, M.; Yang, Y.; Choo, K.-K.R. On data sovereignty in cloud-based computation offloading for smart cities applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 4521–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]